The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Street Photography

Today on 2SER Breakfast, Lisa and Tess talked about a fabulous new exhibition at the Museum of Sydney called Street Photography, that looks at the popularity of commercial street photographers in the 1930s, 40s and 50s.

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

Today we’re all used to having a camera in our pockets - we can snap a photo whenever we like: when we’re all glammed up to party, or while we’re just walking down the street. Photographic technology has come a long, long way.

The first small, personal cameras were the box brownies developed by Kodak. These were slowly becoming affordable with the first couple of decades of the 20th century. But the majority of people didn’t have access to personal photographs except via posed, studio portraits. These were only taken on special occasions.

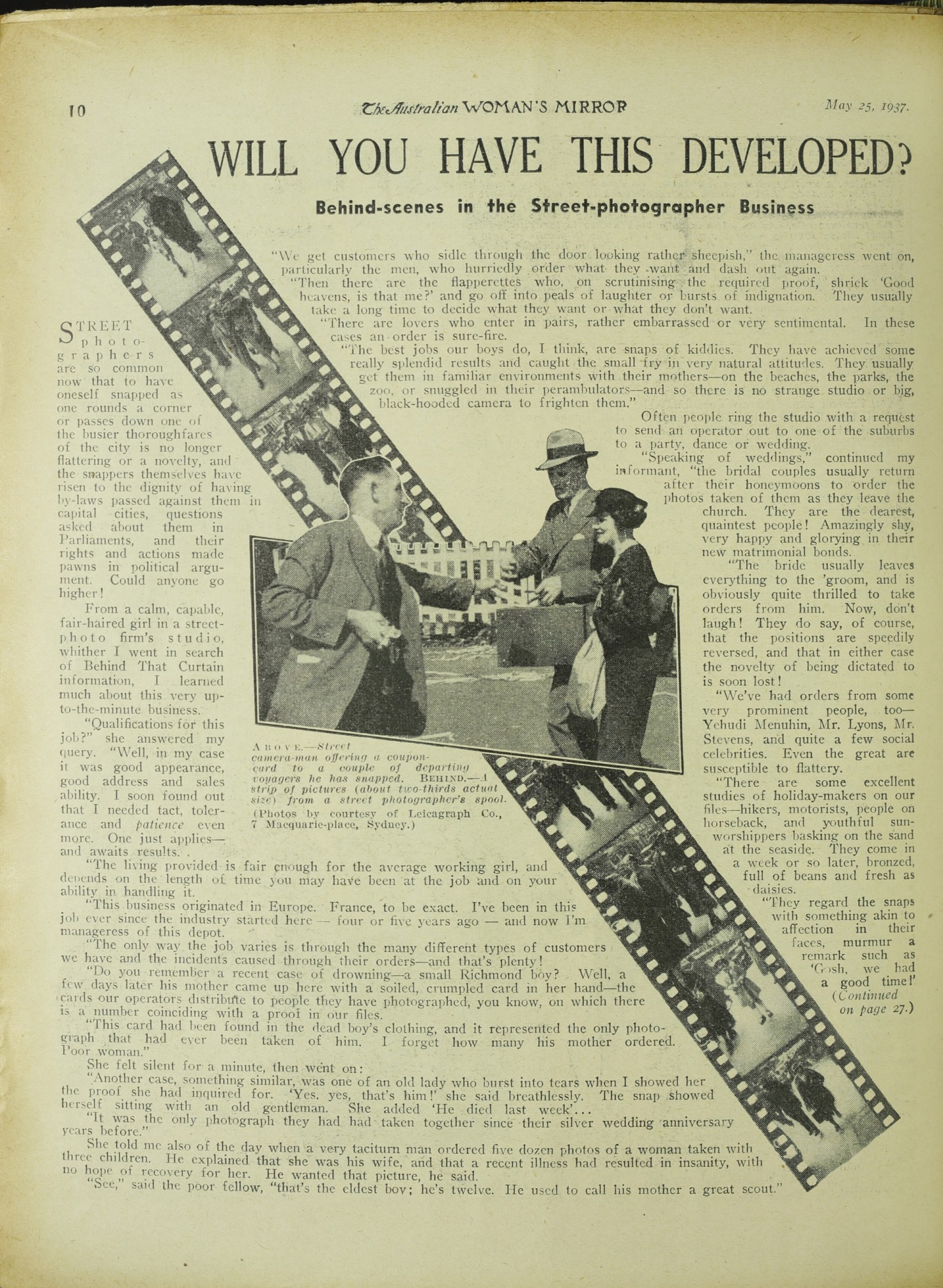

Then in the 1930s, along came the commercial street photographer, snapping photographs as people walked down the street. It was a revolutionary approach to capturing images of people: slightly invasive of personal space, but candid, natural.

This form of photography relied upon novelty and capturing the moment: People meeting friends, dashing for an appointment, out for a day shopping, the first day of a new job. A card with a number was thrust in people’s hands so they knew where to go to purchase a photo. Film was quickly processed to enable customers to pick up their photo the next day.

Today on 2SER Breakfast, Lisa and Tess talked about a fabulous new exhibition at the Museum of Sydney called Street Photography, that looks at the popularity of commercial street photographers in the 1930s, 40s and 50s.

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

Today we’re all used to having a camera in our pockets - we can snap a photo whenever we like: when we’re all glammed up to party, or while we’re just walking down the street. Photographic technology has come a long, long way.

The first small, personal cameras were the box brownies developed by Kodak. These were slowly becoming affordable with the first couple of decades of the 20th century. But the majority of people didn’t have access to personal photographs except via posed, studio portraits. These were only taken on special occasions.

Then in the 1930s, along came the commercial street photographer, snapping photographs as people walked down the street. It was a revolutionary approach to capturing images of people: slightly invasive of personal space, but candid, natural.

This form of photography relied upon novelty and capturing the moment: People meeting friends, dashing for an appointment, out for a day shopping, the first day of a new job. A card with a number was thrust in people’s hands so they knew where to go to purchase a photo. Film was quickly processed to enable customers to pick up their photo the next day.

Probably few people in Sydney have escaped being ‘snapped’ by the street photographer. He frequents the busy thoroughfares at all times of the day and has become as well known as the policeman on beat duty … – The Argus (Melbourne), 29 April 1937Commercial street photography boomed in the 1930s and 1940s, and continued into the late 1950s, and then fell out of favour. While nearly every family would have probably had these types of photographs in family albums, the genre and art of the street photographer was largely forgotten. The Museum of Sydney has revealed this Sydney moment in time with their new exhibition called Street Photography. There were few examples held in library collections, so they did a public call out for people to look in their family albums and were inundated with over 1500 photos. Photos were taken in major streets, such as George Street, Hunter Street, Martin Place and Pitt Street. The photos show fashions in dress, shoes, hairstyles, across all ages, and the streetscapes behind are also really intriguing. They reckon in its heyday - in the late 1930s - about 10,000 people in NSW were purchasing snapshots from commercial street photography companies every week. The exhibition was the inspiration of photo-media artist Anne Zahalka, and her contemporary photographs of descendants of subjects in the original photos accompany and complement the exhibition. Anna Cossu has curated the exhibition, and had the extraordinary task of sifting through all the photographs sent in. One of the most amazing finds were some rolls of unprocessed film. These uncensored photos reveal the work of the street photographer: how they framed shots, the number of shots they took, and how they moved along their patch in the street. I’ve already seen the exhibition once, but I’ll be heading in there again - there are so many absorbing details in this evocative exhibition of a lost photographic genre providing a glimpse of everyday street life in Sydney. It’s a must for every city connoisseur. It’s on until July, so there’s no excuse to miss it! Head to the Sydney Living Museums website for further information about the exhibition and to read more about the history of street photography in Sydney: https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/exhibitions/street-photography https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/street-photography-stories

The Australian woman's mirror, 25 May 1937, p10 via Trove

The Australian woman's mirror, 25 May 1937, p10 via Trove

Categories

Decorating the city

Christmas tree in Hyde Park 7 December 1962, City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 48/3060)

Christmas tree in Hyde Park 7 December 1962, City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 48/3060)

Preparations for Christmas, The Empire, 24 December 1859, p4 via Trove

Preparations for Christmas, The Empire, 24 December 1859, p4 via Trove

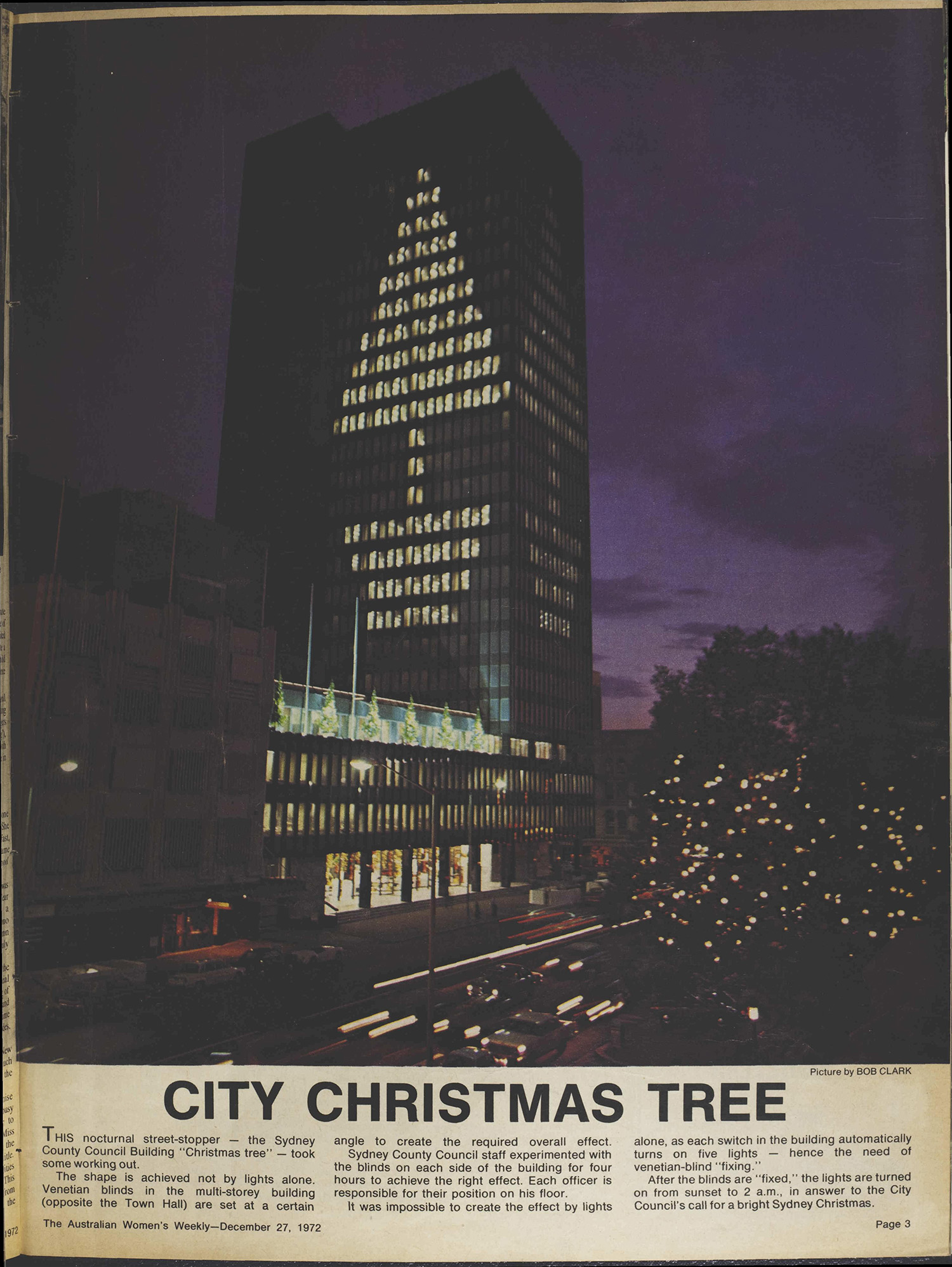

Apparently there was a lot of venetian blind tweaking to get this effect in the Sydney County Council building on George Street in 1972! City Christmas Tree, Australian Women's Weekly, 27 December 1972, p3 via Trove

Apparently there was a lot of venetian blind tweaking to get this effect in the Sydney County Council building on George Street in 1972! City Christmas Tree, Australian Women's Weekly, 27 December 1972, p3 via Trove

Categories

Ocean baths

Wylie's Baths, Coogee c1915, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXE 1028, f56)

Wylie's Baths, Coogee c1915, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXE 1028, f56)

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

Before there were ocean baths, people were swimming, or bathing, around the harbour. For a lot of the 19th century areas around the harbour, like Woolloomooloo, were netted off for people to swim, like Nielsen Park and Balmoral are today. As Sydney Harbour became increasingly polluted however, the fresh saltwater on the coast promised a less smelly and healthier swim. Sydney doesn't have the oldest baths - Newcastle and Wollongong have ocean baths much older - but our ocean baths have been central to the development of swimming, surf lifesaving and Sydney beach cultures. The safest sea-bathing was initially available in the municipalities of Randwick and Waverley in the natural and 'improved' pools on Coogee, Bronte and Bondi beaches. They date from the 1880s, predating the legalisation of daytime surf bathing. The earliest ocean pools were often segregated too - very few people actually wore bathing costumes in those days so protecting swimmers' modest and respectability was a prime concern. Many of these baths were privately run, and one of the most famous of these were Wylie's Baths that were built at the southern end of Coogee Beach in 1907. They were established by Henry Alexander Wylie, a champion long-distance and underwater swimmer. His daughter Wilhelmina (Mina) Wylie was one of Australia's first female Olympic swimming representatives, along with Fanny Durack. Many of the ocean pools in the beach side suburbs that developed further up and down Sydney's coast were built in the Depression of the 1930s as unemployment relief and public work schemes. The Shelley Beach and Oak Park Baths at Cronulla both have lovely art deco change rooms from this period. Bronte Baths c1935, by Sam Hood, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home & Away 5304)

Bronte Baths c1935, by Sam Hood, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home & Away 5304)

Categories

Whaling in Sydney

'Shooting the harpoon at a whale' from book 'Field sports &c. &c. of the native inhabitants of New South Wales' by John Heaviside Clark, London 1813, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an8936144)

'Shooting the harpoon at a whale' from book 'Field sports &c. &c. of the native inhabitants of New South Wales' by John Heaviside Clark, London 1813, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an8936144)

Whaling Station, Mosmans Bay, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV1/54)

Whaling Station, Mosmans Bay, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV1/54)

Categories

Grab your partners for the Balmain Polka

Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (M MUSIC FILE/SPA)

Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (M MUSIC FILE/SPA)

Listen to Lisa and Sean on 2SER here

Music has always been an integral form of community entertainment. Dance music and songs are part of our popular culture today, and the same was true of Sydney in the 19th century and a flourishing music publishing industry brought sheet music into the homes of the upper and middle classes. An interesting musical family in Sydney were the Spagnolettis. Signor Ernesto Spagnoletti (1804-1862) and his son, also Ernesto Spagnoletti (1837-1871) helped shaped musical life in colonial Sydney. Originally from Cremona in Italy (home of Italian violin making), Ernesto senior's father Paolo was a violinist, orchestral leader, and composer who taught violin at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Ernesto senior entered the academy himself in 1825, studying under Henry Bishop and Nicholas Boscha. We've previously highlighted the musical career and scandal of Nicholas Boscha and Anna Bishop (wife of Henry). The Spagnoletti family - Ernesto, his wife Charlotte (also from a musical family) and their six children - migrated to Sydney, arriving in August 1853. Ernesto senior set himself up as a language and musical tutor. He started taking pupils in Italian and English, singing and piano, and was associated with St Stephen's Church at Newtown and later organist at St John's, Bishopthorpe. He must have been delighted when his former teacher Nicholas Boscha and fellow-student Anna Bishop turned up in Australia for a tour in 1855-56. Ernesto performed with Anna Bishop in her Sydney concerts in December 1855. Sadly he also presided over the music at Bochsa's funeral in January 1856. Ernesto senior composed a number of waltzes and polkas that were published in the 1850s, including the New Bazaar Waltz (1854), The Simla Polka (1857), The Woolloomooloo Octave Polka (1858), and The Cornstalk Galop (1859).The song Cooey! An Australian Song (1860) had lyrics written by 'An Australian Lady', a singer named Jane Messiter, and was performed by his daughter Nina Spagnoletti. I think my favourite is the song Your Willie has returned dear (1859). Ernesto junior followed in his father's footsteps. He too was a professor of music, pianist, vocalist, organist, and composer. The son took a distinctly patriotic approach to his musical compositions, celebrating the developing Sydney suburbs and the lovely ladies therein. With the wonders of digitisation, we can now all learn to play and enjoy The Balmain Polka (1857) - which was "Respectfully dedicated to the ladies of Balmain" - along with the Woolloomooloo Schottische - "respectfully dedicated to the Ladies of Woolloomooloo" - (1858; second edition 1860), The Sydney Schottische - "dedicated to Miss Brown of Balmain" - (1860), The Sydney volunteers polka (1861), and the St.Leonards Schottische (1862), the latter features on the cover of the sheet music a lovely coloured view across the harbour. Ernesto junior also composed An Australian Christmas Song (1863) which celebrates the sun, birds and flowers. I think all Australians should learn this song: Courtesy National Library of Australia (MUS N JAF m 786.4052 A938, The Australian Musical Album for 1863, p10)

Courtesy National Library of Australia (MUS N JAF m 786.4052 A938, The Australian Musical Album for 1863, p10)

Categories

Sam Willis and James Daybell, Histories of the Unexpected: how everything has a history

Sam Willis and James Daybell, Histories of the Unexpected: how everything has a history

Sam Willis and James Daybell, Histories of the Unexpected: how everything has a history

Atlantic Books, 2018, 465pp., ISBN: 9781786494122, (h/bk), AUS$39.99

Histories of the Unexpected: how everything has a history, by British celebrity historians Sam Willis and James Daybell, is based on their popular podcast of the same name (which you can find here). Willis and Daybell have joined forces to follow through on some of our best-known historical themes in search of some very strange connections. The authors outline their intentions upfront: they want to tackle the easily recognised from “the Tudors, to the Second World War, from the Roman empire to the Victorians, but they want their readers to think about history as we know it 'via entirely unexpected subjects' (p. 1). The book is a terrific survey of the essential, the everyday and the quirky. Written in an informal and highly-engaging style, this is a book for everyone. There is a chapter on needlework connecting histories of abandoned children, racism and murder (pp. 118-29), one on hair connecting histories of memory, love and Arctic exploration pp. (183-94) and one on cats connecting many stories about an animal that is, today, for many a little friend (pp. 332-44). History is not always pleasant or polite. Indeed, in many instances, history reveals deliberate cruelty and gross violence. As engaging as these authors are, there is still much in this volume that is traumatic. Humans have done, and continue to do, dreadful things to each other and to our environment. As Willis and Daybell are happy to frolic through the centuries, they are not afraid to draw our attention to more serious episodes of continuing relevance. This book is beautifully laid out and includes a bibliography and an index, for those who have had their curiosity piqued rather than fully satisfied and want to know more. There are some lovely illustrations supplementing the text and detailed picture credits list these works, easily facilitating additional research. Histories of the Unexpected is like a bowl of lollies. You can gorge yourself in just a few sessions or have it, just sitting there, to dip into every now and then. The outcomes of these histories—gloves, clocks, boxes and much more—are all very familiar. But the curious details of these historical narratives are quite surprising and so make this book a very informative read. There are some serious messages but it’s also great fun. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, November 2018 Visit the publisher's website here.Categories

Stephen Knight, Australian Crime Fiction: a 200-year history

Stephen Knight, Australian Crime Fiction: a 200-year history

Stephen Knight, Australian Crime Fiction: a 200-year history

McFarland Books, 2018, 301pp., ISBN: 9781476670867 (p/bk), US$45.00

Stephen Knight’s new work Australian Crime Fiction: a 200-year history is a re-working and critical updating of his seminal text Continent of Mystery: a thematic history of Australian crime fiction, first published in 1997. This recently released volume tackles the vast corpus of Australian crime fiction chronologically, rather than thematically. Knight systematically explores five time frames: Earliest Stories to the First World War (1818-1914); Across and Between Two Wars (1915-1945); Towards Independence (1946-1979); Australia Stands Alone (1980-1999); and Patterns of the Present (2000-2017). Themes are still easy to pursue with clear subheadings for sections as diverse as City Mysteries, Amateur Detectives, Indigenous Crime Fiction and Historical Crime Fiction. Knight’s skill in unpacking complex issues around gender across the genre, is on full display in his erudite discussions of men and women as producers of, and protagonists within, crime fiction. This volume also looks at what makes crime fiction produced in the Southern Continent uniquely Australian. Yes, murder is universal (as are the main motives to commit murder including love, money and to cover up another crime). So, too, are other types of crimes such as property offences. Yet, Australia—a land in which the role of crime is crucial to the “national historical formation” (p. 1)—quickly developed a distinctive style of crime story: shaped, in part, by convictism as well as by bushrangers, the goldfields and the squattocracy. As Knight asserts, this work analyses this distinctiveness and seeks to understand Australian crime fiction “as stories that are focused, at least in significant part, on Australia, its citizens, their concerns and contexts” (p. 1). Crime fiction is the world’s most popular genre with devotees found across Australia and around the world, yet locally produced crime fiction was not always embraced and was, indeed, often ignored. One of the main offenders in overlooking this type of storytelling was the academy; crime fiction routinely dismissed in favour of more ‘serious’ scholarship. A key turning point in the treatment of crime fiction occurred when Knight wrote his important essay: “The Case of the Missing Genre” in 1988. Appearing in Southerly, this piece noted that crime fiction “set and produced in Australia is an intriguing subject, but so is the fact that as a genre it has been almost entirely overlooked” (p. 235). Knight has, over decades of research, redressed this glaring omission. Taking up a once unfashionable cause, he has systematically demonstrated the importance of crime fiction to understanding Australia’s cultural and literary histories. Many high-profile scholars have added to our knowledge in this area (including Ken Gelder, Toni Johnson-Woods and Lucy Sussex, to name just a few) and hundreds of research-focused students have now explored various aspects of one of our favourite forms of storytelling. To claim a work is ‘essential reading’ in a book review is a well-worn cliché. It is, however, very fitting in this case. For those with interests in crime fiction, or for those wanting to contextualise other types of Australian literatures, this book is a must have: for researchers to consume cover-to-cover; for students to have as a staple reference tool; and for crime fiction enthusiasts to use as a handy catalogue when looking for their next novel or short story to read. Australian Crime Fiction is a clear and pacey history of an important genre. All the big names of Australian crime writing are discussed alongside a few names that will be new to many readers, with the evolution and the expansion of crime tales driving the text. Inevitably, the coverage of such a vast amount of material and its compression into a single volume make some sections in Australian Crime Fiction feel a little rushed. In compensation, the book includes a very useful bibliography and index allowing for easy follow up of a particular author or title. Knight concludes his latest book with an observation on how much new crime fiction material is produced in Australia each year and argues a “new analysis will be needed in another twenty years at most” (p. 273). He also, modestly, suggests Australian crime fiction is still a “far too little-known popular literary form” (p. 273). I argue this final claim is inaccurate: the crime story in Australia is now a well-known and well-researched artform. Knight’s history is a testament to crime fiction’s durability and the (somewhat delayed) acknowledgement of, and appreciation for, a dynamic genre that has given us everything from mass-produced pulps to prize-winning novels. This book is also a symbol of one man’s career and his persistent lobbying for the acceptability of a once-neglected chapter in the Australian history of writing, publishing and reading. Buy, borrow or otherwise legitimately acquire your own copy of Australian Crime Fiction. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, November 2018 Visit the publisher's website here: https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/australian-crime-fiction/Categories

Remembrance Day: 100 years on

The Sydney Mail, 20 November 1918

The Sydney Mail, 20 November 1918

Last Sunday, 11 November, marked 100 years since the official end of World War I. Initially called Armistice Day, it became known as Remembrance Day after the end of World War II. An article in the Dictionary by Dr Neil Radford has described what that day was like back in 1918.

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

By the time the end of the war came, more than 60,000 Australians had been killed and 160,000 wounded, many suffering both physical and mental disabilities. Rumours of the end of the war came a few days before the actual signing of the Armistice and on 8 November (or 'False Alarm Friday'), crowds filled the streets of Sydney and businesses closed as people celebrated well into the night. Finally on the evening of 11 November official news was received that the Armistice had been signed. In response, church bells rang, trains and ferries sounded their horns, and cheering crowds once again assembled in the streets. By 9pm, the crowds in Martin Place, Pitt Street and George Street were so dense that transportation into the city had to be suspended. The following day was declared a public holiday as the celebrations continued. The bell in the General Post Office tower rang for 10 minutes from 9am and then for five minutes every half hour until noon. Crowds filled the city once again, waving flags and throwing confetti. An effigy of the Kaiser, the German Emperor, was hanged and burned from the buildings of AMP and the Sydney Mail newspaper in the city, and in other Sydney suburbs. The Governor, Premier and Lord Mayor spoke in Martin Place and ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’ were sung. The celebrations continued the following day, with a march of some 6,000 returned soldiers and sailors followed by a gathering in The Domain of an estimated 200,000 people. Although overshadowed somewhat by ANZAC Day celebrations in Australia, Remembrance Day has been commemorated around the Commonwealth at 11am on 11 November every year since 1918. The significance behind this time relates to when the guns on the Western Front fell silent – at 11am on 11 November 1918 – and the Great War was finally over. Further reading: Dr Neil Radford, Celebraitng the end of World War I, Dictionary of Sydney https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/celebrating_the_end_of_world_war_i Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Nicole! Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.Categories

Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall, A New History of the Irish in Australia

Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall, A New History of the Irish in Australia

Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall, A New History of the Irish in Australia

New South Books, 2018, 448pp, ISBN: 9781742235530 (p/b), RRP: $34.99

In 1986 Patrick O’Farrell published The Irish in Australia. At the time, the book was both feted and criticised for being on the one hand seminal and yet on the other, rather controversial. In it, O’Farrell made some rather large claims for the impact of the Irish on Australia’s development as a nation. He argued that their presence as a substantial minority, both as convicts and later as free settlers, shaped the emergence of a particular culture and national character. Neither formed in the wild terrors of the bush, nor on the bloodied shores at Anzac Cove, the Australian national identity was, according to O’Farrell’s thesis, actually the product of longstanding Catholic Irish and Protestant English conflict. And this religious, political and cultural discord had profound significance, for out of it was born an egalitarian and democratic Australia. Simplistic, divisive and very partial to be sure. Then again, most national myths often are. In recent years, ‘national identity’ and its formation has become a rather hot potato amongst historians, politicians and the general public at large. The pioneering bush legend of the nineteenth century, has been over taken by the ‘baptism of fire’ Anzac story - much to the head shaking of many. (For starters, where were all the women?) Likewise, the oft-quoted expression ‘it’s Un-Australian’ is today utilised in political rhetoric, in satirical rebuffs and cartoons lampooning that same rhetoric, in advertisements, merchandising and at all sorts of national sporting events. At times, it can be used in highly amusing ways. However, it is also a lazy, simplistic soundbite, and suggests that there are common characteristics that we all share that stem from a particular magical moment, specific event, lived experience, foreign catastrophe. But just like the creation story in Genesis, all national myths are just that – fabricated and created to define an ‘imagined community.’ Certainly, the Irish contributed in profound and important ways in shaping the society and culture of settler Australia, and continue to do so today. Yet they are just one influence amongst a myriad more. In the thirty odd years since O’Farrell’s book first appeared, Irish-Australian studies has become increasingly popular both within academia and through the endeavours of independent scholars and family and oral historians. The stories of Irish convicts (or were the almost 50,000 involuntary immigrants’ political exiles?); the orphans sent out after the Great Famine of 1845-1850; the role of the Irish at Eureka and as bushrangers; prominent wealthy colonists and politicians and the trajectory of Catholicism in Australia have all been extensively researched and written about. Yet most mainstream Australian historians have been too willing to subsume the Irish under ‘the British’ umbrella, or ghettoise them as a separate race and disparage them as dangerous sectarian agitators, or have even ignored them as a distinctive ethnic group entirely. And, in the midst of all of this, tired anachronistic stereotypes of the Irish remain. In response to this uneven treatment, Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall’s recent book seeks to balance the scales by offering a new general history of the Irish in Australia. The book ‘aims to take a new look’ at the Irish and it is ‘new’ in various respects.[1] Thus rather than ‘aspire to be a comprehensive account’, instead it focuses upon particular themes and issues. Race, gender, crime, mental health, employment, politics and religion are all here explored, set against the backdrop of Australia, with one eye on Ireland and the other on the wider Irish diaspora in America, England and indeed elsewhere. The book is divided into three sections. Part one explores race and sensibly starts out with an examination of the long-held idea of the Irish as a separate and inferior race from the rest of the British population. This is a theme which infuses the book. It was particularly germane to Irish Catholics who had long been perceived as poor, un-educated, ignorant and deeply superstitious. They were deemed (by their English overlords at least) to be physically different too. With their seemingly Simian features and indecipherable brogue, to many they were savages and atavistic brutes. Yet at the time of white settlement in Australia, they also perched awkwardly on the colonial hierarchical ladder. Likened to non-whites and Indigenous Australians, at the same time, they were ‘similar in significant ways to the white British’. And so, the Irish were not to be exterminated, nor excluded but rather, they were to occupy a difficult liminal space. For the Irish themselves, this was sometimes a boon, at other times a heavy burden.[2] Their relationship with Indigenous Australians and Chinese sojourners is explored in detail over two comprehensive chapters. In a nutshell, the authors present a nuanced overview of the Irish as both colonised by the English, and colonisers in Australia. Because, as they suggest, ‘Irish people were part of the story of Australian colonisation in all its complexity.’[3] Some Irish befriended or inter-married with the first Australians, others participated in the brutal violence of the frontier wars. A few were involved in Christian missionary efforts to teach and ‘enlighten’, whilst others later machinated with the removal of ‘half caste’ children from their families. Many more were simply indifferent. Likewise, the Irish had a complex relationship with the Chinese. Intermarriage was quite common between Irish women and Chinese men, but so too was Irish agitation for stricter immigration restriction of the ‘yellow moon faced celestials’. After Federation, many working Irishmen supported the white Australia policy. It was a question of job security and economics and yet many Irish Australians also hoped this stance on race would lead to their own full acceptance within British-dominated Australian society. Whilst this was increasingly the case, longstanding prejudices continued, and the Irish were still rather vulnerable. Many hopeful immigrants were rejected at the border, and during times of social unrest and upheaval, Irish-Australians were deported for ‘political’ offences. It was transportation all over again, only this time in suitable antipodean fashion - in reverse. Section two examines ‘stereotypes’ – from the popular, often crude depiction of the Irish in literature, poetry, the press and on the stage, to the idea of the Fenian and the terrorist. In between, there was the buffoon comedian and the sozzled drunkard. All were exploited for political purposes at times, and all harked back to the idea of the Irish as a different race. Such negative perceptions and hackneyed typecasts were regularly used to discriminate when it came to employment. ‘No Irish Need Apply’ was a common sign in shops and businesses through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century. Not just here, but also in America and across the Irish sea in England. In turn, the Irish responded with their own ‘Catholic preferred’ notices. Often then, racial prejudices were intimately entwined with religious ones. In many respects, they still are today. Crime and madness are examined in two subsequent chapters and explore whether or not the Irish were more criminal or more mad than others. On occasion, the injurious stereotypes of the Irish had profound consequences for both the criminal and the lunatic. But again, the nuance of the authors' research comes through, as the book also examines the Irish who policed, condemned and punished the criminals and those who committed, observed and cared for the insane. The Irish on the outside, beyond the high walls of the gaols and the asylums, could also have a profound influence on just who was incarcerated inside them. The theme of section three is politics – both politics in Ireland and Irish involvement in Australian politics from the colonial era and into the twentieth century. It explores Australian-Irish politicians and premiers, sectarianism, the turbulent years of World War One and the bitter disputes over conscription, to the troubles in post war Ireland. The epilogue briefly examines Irish Australia in the twenty-first century – particularly immigration and Australian responses to the political situation both here and in Ireland since 1945. The book is highly readable and the authors engage with the historiography in a lively and approachable manner. It is illustrated by a fabulous cohort of cartoons and there are a number of simple, illustrative graphs. It is comprehensively referenced and indexed and offers an astonishingly impressive bibliography. Throughout, Malcolm and Hall acknowledge that the book raises many questions that only further research will be able to answer. At first, I found this admission of ‘more research required’ rather strange, even somewhat disconcerting. Later, on reflection, and after I had gone away to look up more information about the ten Irish prisoners who died on hunger strike in Belfast’s Maze Prison in 1981, the historian in me remembered that history books are never finished. Rather, they are merely a contribution at a particular time, to an existing, on-going and continuing discussion. Over identities and politics, culture and society, race, gender and class, oppressors and oppressed. Some histories offer mighty contributions, as does this one. And a very balanced and yet thought provoking one it is too. Dr Catie Gilchrist November 2018 Visit the publisher’s website here: https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/new-history-irish/ Disclaimer: Catie Gilchrist was engaged as a researcher for this book in 2014, looking at records from the Gladesville Asylum in Sydney, New South Wales. Footnotes: [1] Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall, A New History of the Irish in Australia, New South, Sydney, 2018, p 18 [2] Ibid, pp 46-47 [3] Ibid, p 72Categories

A day at the races

Northern end of Hyde Park in 1842, several years after the racecourse had closed, by John Rae, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV*/Sp Coll/Rae/16)

Northern end of Hyde Park in 1842, several years after the racecourse had closed, by John Rae, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV*/Sp Coll/Rae/16)

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

How long did it take to establish a racecourse in Sydney after 1788? Well, the answer to that is not very long! When he got to Sydney, one of the first things Governor Macquarie did was to lay out and establish the names of a whole lot of streets, like George and Elizabeth Streets, and also to proclaim Hyde Park. That was in 1810. Within just 2 months, officers of the 73rd Regiment established a racecourse around the park. Apparently the regiment argued the races were essential, since a race course would help improve the breed of horse available to the military, but I think it's safe to say that the regiment was desperate for some entertainment and a chance to let off steam and to race and gamble. The first official horse race in Sydney was run in Hyde Park in mid-October 1810. Perhaps some of the giddiness of the first race meet was tempered by the Governor's order that no stalls could be set up around the course, and that "Gaming, Drunkeness, Swearing, and Fighting" were NOT permitted. The first 'meet' was a three day event, with generous prizes including a purse of 50 guineas and a silver cup, of 'very fine worksmanship'* which was given by the Ladies of the Colony, also valued at 50 guineas. Sydney Gazette, 13 October 1810, p1 via Trove

Sydney Gazette, 13 October 1810, p1 via Trove

Detail from 'A Sketch of the Town of Sydney 1821' showing the top of Macquarie Street and the Hyde Park Racecourse around the edge of the park. The horse barracks are where the State Library stands today. Courtesy: Mitchell Map Collection, State Library of NSW (Z/M4 811.16/1821/1 )

Detail from 'A Sketch of the Town of Sydney 1821' showing the top of Macquarie Street and the Hyde Park Racecourse around the edge of the park. The horse barracks are where the State Library stands today. Courtesy: Mitchell Map Collection, State Library of NSW (Z/M4 811.16/1821/1 )

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and the former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Lisa! You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio

Listen to the podcast with Lisa & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20 am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Categories