The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Archaeology in Sydney

Tim Owen inspects archaeological investigations in Western Sydney. Photograph by Sharon Johnson (GML Heritage)

Tim Owen inspects archaeological investigations in Western Sydney. Photograph by Sharon Johnson (GML Heritage)

Listen to Tim and Tess on 2SER here

Archaeologists in Sydney work across many different fields. Historical archaeology looks at the period from 1788 until today but I also study Aboriginal archaeology across Sydney, looking at the evidence of the 50,000 years or so of Aboriginal occupation here. Archaeologists work on different kinds of sites too, some of high cultural significance, or those in a commercial setting that are going to be developed or need to be conserved. One site with high significance, the archaeological site on Bridge Road of first Government House on Bridge Road in the city, is nationally heritage listed and is important to colonial history in many ways, including as a site of first contact between the British colonisers and the Gadigal people. Arabanoo, Bennelong & Colebee were all incarcerated here after they were kidnapped, and held in chains in the yards. There's also an archaeological record of Aboriginal people being inside Government House through the materials they brought in and produced here and that have produced tangible evidence of Aboriginal people of their presence. Archaeologists are often called in to provide an assessment of a site that is less obvious in its significance. Prior to its development for something like a new housing estate or factory, a site will have been subject to investigation and possibly excavation before construction starts. As the city grows, quite a lot of this work takes place in western Sydney. Western Sydney is just full of Aboriginal archaeology, Aboriginal heritage, Aboriginal places and Aboriginal meaning. It's a massive cultural landscape, with tangible and intangible values. Intangible values relate to stories, creation, travelling routes, geographical features, trees, plants, animals - all the things that are part of Aboriginal tradition. It's what is referred to as Country, underpinned by spirituality. Material evidence that comes as a consequence of Aboriginal people having lived here for 40,000 - 50,000 years is absolutely everywhere. You'll often find stone artefacts in western Sydney, and art sites and shell middens around the harbour and rivers. There's an extensive range of evidence that helps us to understand the very, very long term occupation of this ancient country by Aboriginal people. Archaeology in western Sydney is often buried rather than being on the surface, and it's the knowledge of the local Aboriginal people that inform the archaeologists and identify sites for excavations and allow us to understand the places that Aboriginal people have occupied for thousands of years. One such site is in East Leppington in south western Sydney where we undertook several months of archaeological research and excavations before construction began on a new residential development. We knew it was an historic landscape when we began as it was the site at of an early colonial land grant, and we could see the old homestead sitting on the hills. When we began to talk to local Aboriginal people however, they told us about a view corridor through the hills. When you went up one of the hills and faced one way, you could see the Blue Mountains. Face the other way and you could see the three CBDs, Parramatta, North Sydney and the city CBD with the Harbour Bridge in the distance. This was an amazing view now, but it was also, importantly, connected to a long Aboriginal tradition. From here you could see where everyone was across the Cumberland Plains, which had significance for community, travelling routes and corroborees. This was a strong intangible connection and although there was not a lot of archaeology at the top, when we began investigating lower down these hills, we found particular places in the landscape with lots of archaeological evidence showing Aboriginal people had come back to the same location over thousands and thousands of years. We were able to prove this through stratigraphic excavation, a kind of three dimensional puzzle, that allowed us to date the evidence we found. With OSL (Optical Stimulated Luminescence) dating of grains of sand in the alluvium that had been deposited by flooding and buried the older archaeology, we found that it had been set down over 10,000 years or so. We also applied carbon dating to hearth and cooking residues. We had also identified changes and developments over time in the artefacts left behind as materials and different methods of production allowed for much more refined tools, and these dating tools helped us to work out when these developments had taken place. History Week 2019 will be launched on Friday, and Tim Owen will be speaking at a special History Week event, 'Unearthing Memory and Myth', at GML Heritage in Surry Hills next Thursday at 6pm. Join historians and archaeologists from GML Heritage for an evening of lightning talks exploring cultural landscapes, archaeology, forgotten ruins, memory and mythology. Tim Owen will present on concepts of memory and use of place through the lens of Aboriginal people’s connection to land over thousands of years. What are some of the places we forget? As part of her 2018 NSW History Fellowship, Minna Muhlen-Schulte has been researching the ruins and memorials of Second World War internment camps in Victoria. Archaeologist Brian Shanahan has worked in Ireland, Victoria and New South Wales for twenty years and will discuss myth, memory and material in the Irish landscape. Angela So has over 10 years’ experience in archaeology, historical research and interpretation planning and she will explore the ways in which we can interpret memory landscapes for wide range of audiences and formats. Find out more and book your tickets online here: https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/unearthing-memory-and-myth-tickets-62831339227 There are too many great talks, tours, exhibitions and events being presented across Sydney to list here, so head to the History Council of NSW website and check the calendar and downloadable program for other great History Week events so you can plan your week: https://historycouncilnsw.org.au/ Some of our highlights include:- The 2019 NSW Premier's History Awards are being held this coming Friday night at the State Library of New South Wales, and we're very excited! Click on the link here for the shortlists in each category.

- On Tuesday 3 September, Professor John Maynard is presenting the Annual History Lecture, 'Counter Currents – Aboriginal men and Women at the Heart of Empire'. Bookings through the History Council website here.

- Historian and regular Dictionary of Sydney presenter Dr Lisa Murray is giving an illustrated talk on the Block Plans of Sydney at Customs House on 1 September (book HERE) and another on the Devonshire Street cemetery on 4 September (book HERE). The City of Sydney's history team are also holding some special events for History Week and the final weekend of Cartographica - Sydney on the map, a great free exhibition at Customs House that examines the history of maps of the City of Sydney. Check their program here.

Categories

The Witch of Kings Cross

A Weird Story By A Gifted Fifteen Year Old Authoress, Smiths Weekly, 6 January 1934, p16 via Trove

A Weird Story By A Gifted Fifteen Year Old Authoress, Smiths Weekly, 6 January 1934, p16 via Trove

Rosaleen Norton 1943, by Ivan Ives, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales Courtesy ACP Magazines Ltd. (ON 388/Box 020/Item 059)

Rosaleen Norton 1943, by Ivan Ives, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales Courtesy ACP Magazines Ltd. (ON 388/Box 020/Item 059)

Categories

Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney

Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney

Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney

Hachette Australia, 2019, pp 1-311, ISBN: 9780733640988, RRP $32.99

Mid-morning, Tuesday 12 January 1904, Watkin Street, Newtown. Four-year-old Mervyn Sly probably did not fully comprehend the horror he stumbled across when he saw his mother lying prostrate on a mattress on the floor of her bedroom. She was dressed only in her underclothing, a calico chemise (a full-length slip.) On her feet were her neatly laced up boots. Her throat had been cut so savagely that her head was semi-severed from her body and she was completely soaked in her own crimson blood. But he knew something was clearly ‘wrong with Mammy’ and he went outside to fetch his oldest brother who went upstairs to investigate.[1] Here, seven-year-old Bedford Sly saw his lifeless, blood drenched mother. He then made another terrible discovery; his father, fully dressed save for his usual hat, was lying in a similar condition close by on the bedroom floor. An open cut-throat razor was still tightly gripped in his right hand. They were both quite dead and the floor of the room was swathed in a thick red river. It was a truly ghastly spectacle and ‘in less than twenty-four hours, the headline ‘Newtown Tragedy’ was splashed across papers nationwide’.[2] Tanya Bretherton’s latest book The Suicide Bride opens with the grim double discovery of the murder-suicide of Alexander and Ellie Sly in Newtown on that fateful summer morning in 1904. It explores the possible motives behind the crime; the subsequent police investigation into it and the coroner’s inevitable, sad inquest. The book steps back to trace Alexander Sly’s own long family history to examine broader ideas of madness and criminal hereditary. It then moves on to reveal the deep and enduring repercussions that Sly’s final dreadful act had upon the lives left behind. This is certainly not a happy read. It is gruesome and grim and it is sadly just one Sydney story of murder-suicide - for there are so many more. It is however, an incredibly powerful, deeply moving story, meticulously researched and beautifully written with both careful nuance and rich aplomb. To his neighbours, Alexander William Bedford Sly (known as Alicks) was an odd and eccentric man. A tailor by trade, in 1903 Alicks found himself out of work due to the depressed state of the economy. He was also prone to violent outbursts and displays of intense spiritual rantings; both were juxtaposed by erratic and unstable hallucinations. His was indeed a volatile persona and to medical and criminological minds in the Edwardian era, this made him a dangerous man, bordering on the criminally insane.[3] And Ellie Sly? Victim or ‘willing’ participant? Whilst her own complicity in her dreadful violent death is not explicitly spelled out, some contemporaries at the time, and indeed the author, subtly suggest that she might have actually been a ‘consenting murder victim’.[4] This is utterly astonishing today, but it was not entirely unknown in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though the early years of their marriage seem to have been happy ones, poverty, mental illness and madness slowly weaved an anxious troubling thread around the couple. Before her awful death, Ellie, like her husband, showed signs of persecution and paranoia. And by 1904, the Sly family were desperate and destitute. Their four surviving children - Bedford (b. 1896), Basil (b. 1897), Mervyn (b. 1899) and Olive (b. 1900) had all been terribly neglected; they were ill fed and emaciated and were often left unsupervised in the streets where they lived. Another child Norman was born in 1902 but he died at the age of 6 months. At the time, his symptoms presented as gastroenteritis but Bretherton speculates that his death might have in fact been caused by arsenic poison, deliberately and lethally administered by one of his despairing parents. This was never proved although, as the author perceptibly reminds us, today ‘strict protocols to screen biological samples for poisons are well developed’ but ‘in 1904, forensic science remained a fledgling field’.[5] Somewhat sinisterly, at the time of the Newtown tragedy, young Olive was actually in the Prince Alfred Hospital recovering from ‘alleged’ food poisoning. The three young boys, then aged seven, six and four were temporarily taken to the Sydney Rescue Home of Hope in Camperdown, a place where ‘friendless’ and ‘fallen’ women gave birth and had their babies removed soon afterwards.[6] Some desperate women came here to recover from a botched illegal abortion, although sadly, many did not recover and left the home in a coffin. A month later, in February 1904 the brothers were sent to the Roman Catholic St Michael’s Orphanage at Baulkham Hills. Their sister Olive was officially adopted and left the Prince Alfred with new parents and a new name, Mollie Ford. We don’t know her later story. For her brothers however, ‘it would be ‘St Michael, not family, who would raise Bedford, Basil and Mervyn.’[7] And for the next few years their lives were structured around religion, rigorous routine and rigid rules of behaviour. On reaching the age of ten, they were all transferred seven kilometres away to the boys’ industrial school at St Vincent’s – also then known as Westmead Boy’s Home. It is all rather grim indeed. But it is in the portraits of the brother’s adult lives where the author’s sociological training really shines through. Eldest son Bedford never shook off the complex trauma that his parents’ death had unleashed. In his early teenage years, he ran away from St Vincent’s and from here ‘he just kept running’.[8] Tragically he did not stay in touch with his brothers. Instead, he lived a lonely, transient life, wandering through Sydney, country New South Wales and South Australia, often moving in and out of gaol, as a vagrant. His own sudden death, occurred on the anniversary of his parent’s death, on 12 January 1955. Reading his sad life story, one actually wonders how he managed to survive his solitary nomadic existence for so long. Happily, middle brother Basil fared rather better. As an adult, he made regular donations to both St Michael’s and St Vincent’s which suggests that his time there had possibly been a positive, affirming one. Somewhere along the way, Basil developed a deep love for poetry and Australian bush ballads, perhaps as a means of escapism, or maybe it was a wistful earning for an idyllic life of freedom. He married happily, but on being widowed early, successfully raised his two daughters alone. Youngest brother Mervyn tried to enlist in the AIF during World War One, but at just five foot and three inches he was deemed too short and was therefore declared ‘medically unfit’. He ultimately became a champion swimmer and pioneer surf lifesaver, managing harbour baths and teaching swimming at various coastal locations on the beaches to the north and south of Sydney.[9] In many respects, The Suicide Bride is a sweeping and at times soaring, family saga. There is a truly shocking twist towards the end which documents another murder-suicide which occurred in Five Dock, Sydney in 1929. But out of tragedy, also emerges a much broader, very rich history of daily life and death in Sydney and its neighbourhoods; religious divisions in the early twentieth century, intemperance and poverty, contemporary gender relations and the miseries of married life for many unhappy couples. Institutionalisation and orphanages, crime and madness, and the role of genes and hereditary are also here intimately explored. The Suicide Bride is ultimately a strong and sincere testimony to the struggle and survival of those born and raised in adverse family circumstances, the repercussions of crime and violence, and the stigma of mental struggle. It is then, a story which will resonate both loudly and profoundly for many today. On finishing the book, I was left oscillating between feeling both utterly bereft and yet also really hopeful. And that is surely the sign of a book that is brilliant, thought-provoking and profoundly emotive at one and the same time. Dr Catie Gilchrist August 2019 Dr Catie Gilchrist is an historian at the University of Sydney. She has written for the Dictionary of Sydney and the St John’s Cemetery project, and is the author of Murder, Misadventure and Miserable Ends: Tales from a Colonial Coroner’s Court (Sydney: HarperCollins 2019) Visit the publisher’s website here to purchase or read a sample of The Suicide Bride: https://www.hachette.com.au/tanya-bretherton/the-suicide-bride-a-mystery-of-tragedy-and-family-secrets-in-edwardian-sydney Footnotes: [1] Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney, Hachette Australia, 2019, p 5. [2] Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney, Hachette Australia, 2019, p 38. [3] Clearly, and with the benefit of hindsight at least, he was a man in need of institutionalisation in, to use the phraseology of the day, one of the state’s many ‘lunatic’ asylums. [4] Although the coronial inquest concluded that she had been murdered by her husband. [5] Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney, Hachette Australia, 2019, p 117. [6] It was founded in 1883 by George Ardill of the Sydney Rescue Work Society. In 1890 it was based in Stanley Street (today known as Gilpin Street) and in 1904 became known as the South Sydney Women’s Hospital until it closed in 1976. [7] Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney, Hachette Australia, 2019, p 194. [8] Tanya Bretherton, The Suicide Bride; A Mystery of Tragedy and Family Secrets in Edwardian Sydney, Hachette Australia, 2019, p 227. [9] According to Bretherton, Florence had possibly been infected by VD by her first husband on his return from World War One.Categories

PN Russell

Mr PN Russell, a generous donor to the Sydney University 1895, The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 7 December 1895, p1171

Mr PN Russell, a generous donor to the Sydney University 1895, The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 7 December 1895, p1171

Listen to Mark and Tess on 2SER here

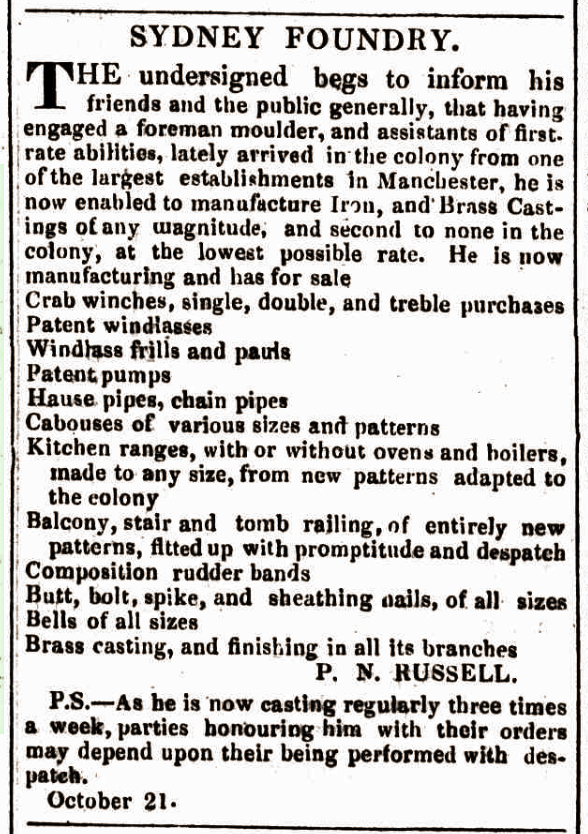

The Russell family, originally from England, arrived in Sydney in 1838 from Hobart where they had established a small business. Sydney, a growing colonial city in the 1830s offered more opportunities and business ventures for the Russells, and Peter and three of his brothers set up as the Russell Bros in Queens Place, an old street north of Bridge Street close to the harbour. In 1840 they expanded into Bridge Street and Macquarie Place with a new foundry and works where they sold imported steam engines and other machinery. Engineering was an emerging field at the time and the Russell brothers were as keen to teach about it as they were to practice. From 1841 Peter gave lectures at the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts about steam power, using a model steam engine they had made to demonstrate his lectures. Advertisement for the Sydney Foundry in the Colonial Observer, 12 November 1842, p603

Advertisement for the Sydney Foundry in the Colonial Observer, 12 November 1842, p603

Assembled workmen at PN Russell & Co c1870-75, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (SPF/504)

Assembled workmen at PN Russell & Co c1870-75, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (SPF/504)

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Categories

What does Margaret say?

Lisa with her treasured 1977 edition of the Margaret Fulton Cookbook

Lisa with her treasured 1977 edition of the Margaret Fulton Cookbook

She also explained to Australians how to eat spaghetti, at the time still a novel dish in the Australian kitchen:

a) A spoon and fork can be used to mix the spaghetti, sauce and cheese

b) Spear a few strands with fork. The spoon will help you coil the spaghetti

c) Wind around fork, just enough for one mouthful, and left neatly from plate.

From what I've seen on Twitter, lots of people still have The Margaret Fulton Crock-pot Cookbook too. It was first published in 1976 and was later re-issued as Margaret Fulton Slow Cooking. (Again, she was ahead of the curve with her emphasis on slow cooking.) Later on she produced a microwave cookbook, and of course, volumes on particular types of cuisine, such as Chinese cooking, baking and so on.

Then in 1983 she released Margaret Fulton's Encyclopedia of Food & Cookery.

I taught myself to cook with my Mum's copy in the 1980s and when a new edition was released 2005 I snapped it up. Whenever there is a debate about cookery in my household, I always ask "What does Margaret say?" and reach for the Margaret Fulton Encyclopedia. (Alternatively, we might also ask "What does Stephanie say?" and reach for the rival Cook's Companion by Stephanie Alexander). Margaret saw her revised Encyclopedia as a compendium of her life's work, with notes, tips and tricks.

She also explained to Australians how to eat spaghetti, at the time still a novel dish in the Australian kitchen:

a) A spoon and fork can be used to mix the spaghetti, sauce and cheese

b) Spear a few strands with fork. The spoon will help you coil the spaghetti

c) Wind around fork, just enough for one mouthful, and left neatly from plate.

From what I've seen on Twitter, lots of people still have The Margaret Fulton Crock-pot Cookbook too. It was first published in 1976 and was later re-issued as Margaret Fulton Slow Cooking. (Again, she was ahead of the curve with her emphasis on slow cooking.) Later on she produced a microwave cookbook, and of course, volumes on particular types of cuisine, such as Chinese cooking, baking and so on.

Then in 1983 she released Margaret Fulton's Encyclopedia of Food & Cookery.

I taught myself to cook with my Mum's copy in the 1980s and when a new edition was released 2005 I snapped it up. Whenever there is a debate about cookery in my household, I always ask "What does Margaret say?" and reach for the Margaret Fulton Encyclopedia. (Alternatively, we might also ask "What does Stephanie say?" and reach for the rival Cook's Companion by Stephanie Alexander). Margaret saw her revised Encyclopedia as a compendium of her life's work, with notes, tips and tricks.

Margaret Fulton was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in 1983 in recognition of service to the media as a journalist and writer in the field of cookery, and in 1997 was recognised by the National Trust as an Australian Living Treasure. Her family has accepted the NSW Government's offer of a State Memorial Service (details are yet to be announced), acknowledging her contribution to our culture and community. She continued producing cook books and encouraging people to aspire to wholesome, simple cooking all her life, but she also encouraged people to be adventurous, and once mastered to "give it the stamp of your personality" and make each recipe your own. And she particularly empowered women to make choices and to enjoy their roles as mothers, homemakers and workers.

One of my favourite recipes is her beef stroganoff (find it here). It is simple, quick, and oh so tasty.

As Margaret says,

"Bon Appetit,

Bonne Cuisine".

Vale Margaret Fulton (1924-2019)

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and the former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Lisa! You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio

Listen to Lisa & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20 am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Margaret Fulton was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in 1983 in recognition of service to the media as a journalist and writer in the field of cookery, and in 1997 was recognised by the National Trust as an Australian Living Treasure. Her family has accepted the NSW Government's offer of a State Memorial Service (details are yet to be announced), acknowledging her contribution to our culture and community. She continued producing cook books and encouraging people to aspire to wholesome, simple cooking all her life, but she also encouraged people to be adventurous, and once mastered to "give it the stamp of your personality" and make each recipe your own. And she particularly empowered women to make choices and to enjoy their roles as mothers, homemakers and workers.

One of my favourite recipes is her beef stroganoff (find it here). It is simple, quick, and oh so tasty.

As Margaret says,

"Bon Appetit,

Bonne Cuisine".

Vale Margaret Fulton (1924-2019)

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and the former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Lisa! You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio

Listen to Lisa & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20 am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Categories

Hollywood nights

'She is 24, has a smile like sunshine, a devastating humor, and stands nearly 5 feet 10 inches in her nylons.', The Australian Women's Weekly, 1 December 1954, p69 via Trove

'She is 24, has a smile like sunshine, a devastating humor, and stands nearly 5 feet 10 inches in her nylons.', The Australian Women's Weekly, 1 December 1954, p69 via Trove

A series of newspaper and magazine advertisements for Arnott's Arrowroot biscuits in 1931 featured the young Doris Goddard of Glebe, The Australian woman's mirror, 19 May 1931, p41 via Trove

A series of newspaper and magazine advertisements for Arnott's Arrowroot biscuits in 1931 featured the young Doris Goddard of Glebe, The Australian woman's mirror, 19 May 1931, p41 via Trove

The Australian Women's Weekly, 3 March 1982, p21, via Trove

The Australian Women's Weekly, 3 March 1982, p21, via Trove

Categories

Living Language: Country, Culture, Community

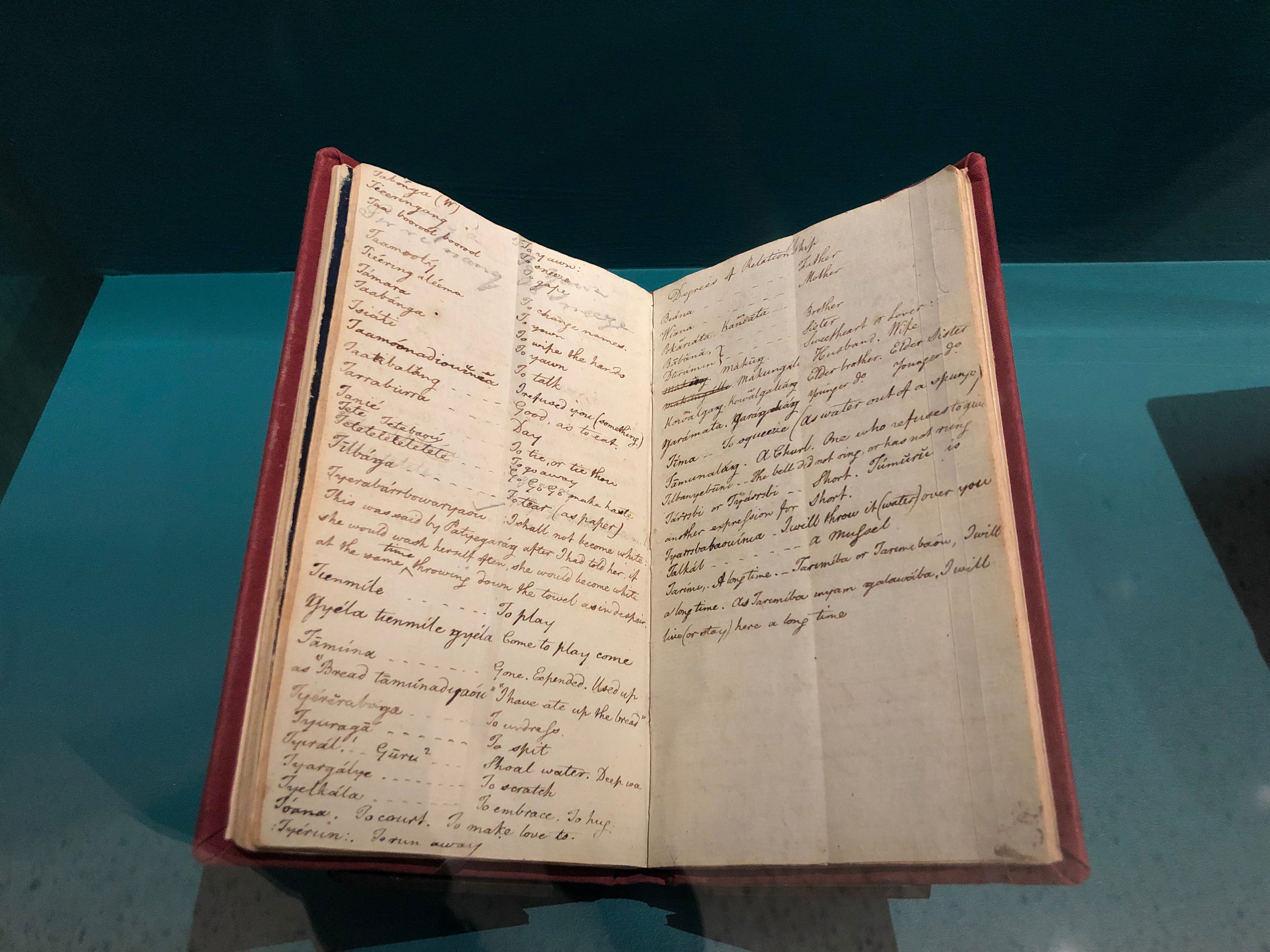

Dawes' notebooks on display in the Living Language exhibition at the State Library of New South Wales

Dawes' notebooks on display in the Living Language exhibition at the State Library of New South Wales

Listen to Ronald and Tess on 2SER here

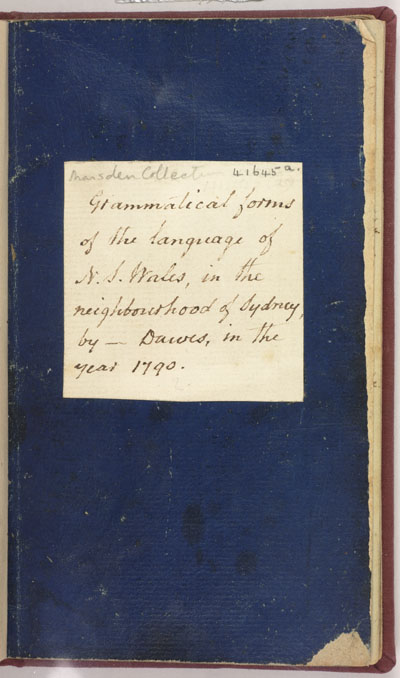

To put together a language exhibition has been a bit of a challenge. Exhibitions tend to be about something you can see and language is usually something you hear rather than see, but we've come up with a great mix of artefacts, pictures, audio and video that celebrates the resilience of our Aboriginal languages using original documents and interviews with language custodians on Country. As part of this mix, it's very exciting to have the notebooks of Lieutenant William Dawes back in the country. Dawes was an officer of the marines on the First Fleet. He was a young man, about 26 or 27, and a scientist and astronomer, but he was also very interested in language and the local Aboriginal people. He became friends with the local people and made lots of notes about his conversations with them. As part of his astronomical work, Dawes moved out of the main part of the colony to the area now known as Dawes Point, where the southern pylon of the Harbour Bridge site. He built an observatory and lived in a small shack where the local people visited him. A young woman named Patyegarang, who we believe was about 15 or 16, became particularly good friends with Dawes, and she taught him the Sydney language. Grammatical forms of the language of N. S. Wales, in the neighbourhood of Sydney, by _ Dawes, in the year 1790, courtesy SOAS University of London

Grammatical forms of the language of N. S. Wales, in the neighbourhood of Sydney, by _ Dawes, in the year 1790, courtesy SOAS University of London

Categories

Jessica North, Esther; The extraordinary true story of the First Fleet girl who became First Lady of the colony

Jessica North, Esther; The extraordinary true story of the First Fleet girl who became First Lady of the colony

Jessica North, Esther; The extraordinary true story of the First Fleet girl who became First Lady of the colony

Allen & Unwin, 2019, pp 1-277, ISBN 9781760527372, p/bk, AUS$29.99

They could have hanged Esther Abrahams. In 1786, the pretty young Jewish woman had attempted to conceal twenty-four yards of pilfered black lace under her petticoats. Worth fifty shillings, thefts of such value technically led to the gallows. But luckily for Esther, she was instead sentenced to ‘exile beyond the seas’ for seven years. Before she was transported, she was incarcerated in the abysmal conditions of London’s notorious Newgate Prison. Here, the sixteen-year-old prisoner discovered that she was ‘with child’ and gave birth to her daughter Rosanna in March 1787. A few weeks later, both mother and infant were removed to the Lady Penrhyn to start their incredible eight-month journey to the other side of the world. The thief and her daughter were to be a tiny part of one of the most remarkable experiments ever undertaken in penal, maritime and colonial history; the British settlement of New South Wales. And both their lives would be profoundly transformed by it. Fast forward to 1814, Esther had given birth to eight more children and was a much-loved grandmother. After twenty-six years together, she was now the well-respected wife of Major George Johnston, who had been one of the leading movers and shakers in the ‘Rum Rebellion’ against ‘tyrant’ Lieutenant-Governor William Bligh in 1808. In her own right, Esther was also a much-revered lady and astute businesswoman and for years, during Johnston’s frequent absences, had successfully overseen his extensive estates in Annandale and elsewhere. Daughter Rosanna had been the first ‘free’ Jewish settler in New South Wales back in 1788. By this date too, she had also become a regarded colonist and a prosperous wife and mother. This is an inspired and remarkable ‘rags to riches’ story. From convict thief to one of the colony’s most respected matriarch’s, Jessica North’s Esther is the fascinating account of a truly remarkable woman, cleverly interwoven with all the leading social and political events of the first three decades of early Sydney. Here we encounter the large and colourful early colonial cast - from the officers of the First Fleet to the convict bolters, Mary and William Bryant, and the ‘convicts made good’ Susannah and Henry Kable. First Australians Arabanoo, Bennelong and Colbee all appear, as does the Reverend Samuel Marsden and the gentleman rogue Dr D’Arcy Wentworth, and later, Second Fleet arrivals John and Elizabeth Macarthur. Life in the nascent colony is vividly, vibrantly and gruesomely explored; desolate isolation, hunger and drought, devastating bushfires and floods, curious and strange wildlife, convict floggings and hangings, and early violent encounters with the Gadigal peoples. All are skilfully entwined within Esther’s own epic saga of personal struggle and survival. The early story of Sydney will be a familiar one to many Dictionary of Sydney readers. However, North’s writing is so utterly beautiful and compelling that reading her prose is akin to hearing the remarkable history for the first time with much wonderment (and at times) great disbelief – because as the old adage goes, ‘truth really is stranger than fiction’. It is also so richly evocative that at times I felt I was watching the drama emerge in real life, that I was right there with them, rather than merely sitting reading a book in a café in Rozelle with a yawning gap of two hundred years between us. This is a book that is also striking, inventive and full of nuance to person, place and period. Indeed, (albeit on a personal note), this is up there with Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (2005) which also had the same deeply profound, spine tingling effect upon me. Meticulously researched over ten long years, North’s depth of knowledge of early colonial history is deep and clear. She has consulted official colonial records, contemporary accounts and journals, and personal letters and diaries. And, as detailed chapter notes explain at the end of the book, in between the spaces and silences of the archival records, the author has used other close sources to re-imagine what possibly might have been the scenario when in fact it cannot be known for sure. It makes for a delightful narrative, and by delineating what is fact from what is fictive in the book, North successfully and skilfully navigates the power of her own soaring imagination to fill in any historical silences, weaving a new thread between history and fiction. Esther is beautifully – actually it is sumptuously – illustrated, and it contains extensive notes and a comprehensive bibliography. It is also indexed marvellously. This book is a triumph. I absolutely loved it. Dr Catie Gilchrist July 2019 Dr Catie Gilchrist is an historian at the University of Sydney. She has written for the Dictionary of Sydney and the St John’s Cemetery project, and is the author of Murder, Misadventure and Miserable Ends: Tales from a Colonial Coroner’s Court (Sydney: HarperCollins 2019) Visit the publisher’s website to purchase or to find a sample of Esther: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/general-books/history/Esther-Jessica--North-9781760527372Categories

Sydney’s Oldest Unsolved Murders

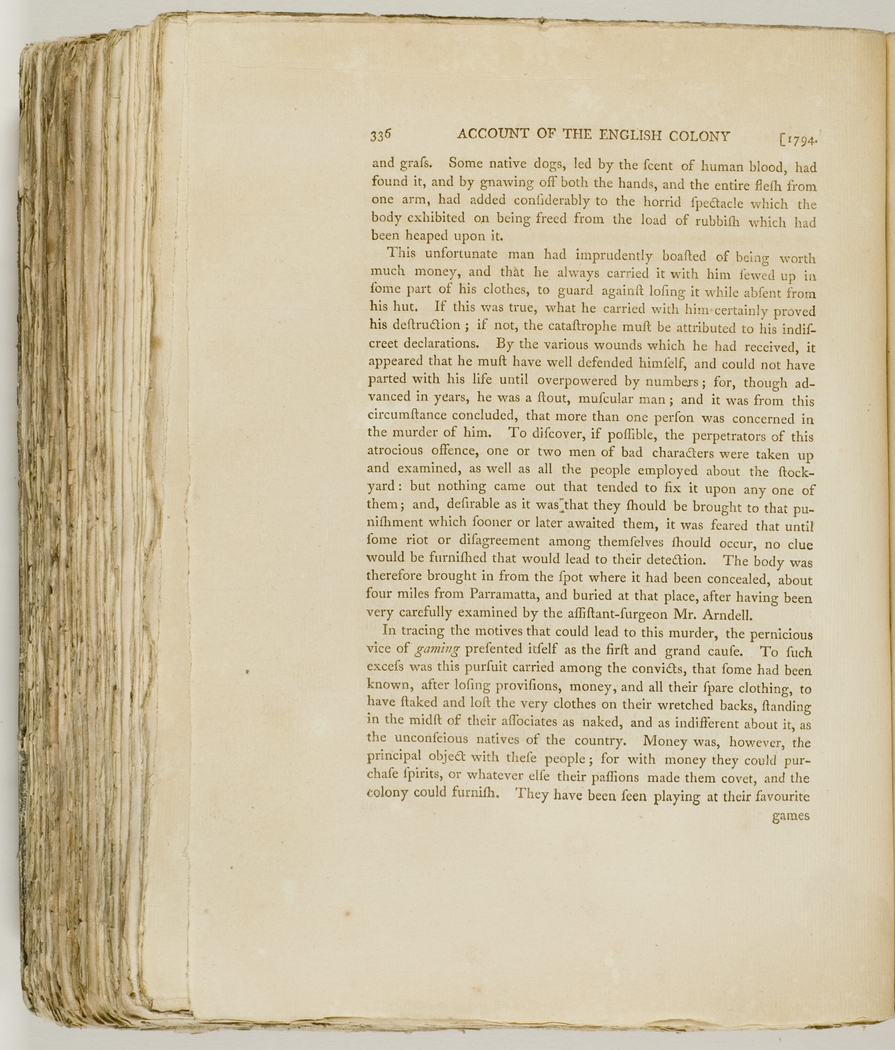

An account of the English colony in New South Wales : with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country, compiled, by permission, from the MSS. of Lieutenant-Governor King by David Collins, London: 1798-1802, courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (Q79/60 v. 1, p335)

An account of the English colony in New South Wales : with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country, compiled, by permission, from the MSS. of Lieutenant-Governor King by David Collins, London: 1798-1802, courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (Q79/60 v. 1, p335)

Listen to Rachel and Tess on 2SER here

In November 1788, a soldier met an untimely, non-work related end when he ‘died at the hospital of the bruises he received in fighting with one of his comrades, who was, with three others, taken into custody and afterward tried upon a charge of murder’. The men responsible for the unexpected death would, however, be found guilty of manslaughter and not murder with ‘each sentenced to receive two hundred lashes’. So, while violence was not uncommon, murder was a relatively rare act and not all of the murders committed in colonial Sydney were solved. Some people just disappeared. It’s possible a murder was committed in late 1788 when a soldier suddenly went missing. There was another case of a missing person in April 1793, just over five years after the First Fleet arrived. David Collins recording that some people: … were taken up at Parramatta on suspicion of having murdered one of the watchmen belonging to that settlement; the circumstances of which affair one of them had been overheard relating to a fellow-convict, while both were under confinement for some other offence. A watchman certainly had been missing for some time past; but after much inquiry and investigation nothing appeared that could furnish matter for a criminal prosecution against them. The first convict in the colony believed to have been a victim of murder, dying at the hands of his fellow colonists, was John Lewis in January 1794. An enthusiastic gambler, Lewis regularly boasted of how he kept his illicit earnings stitched within his clothing. Again, the event is noted by David Collins who wrote that: … an elderly convict, employed to go out with the cattle at Parramatta, was most barbarously murdered. … [The body was found] … covered with logs, boughs, and grass. Some native dogs, led by the scent of human blood, had found it, and by gnawing off both the hands, and the entire flesh from one arm, had added considerably to the horrid spectacle which the body exhibited … Some brief inquiries were made in an attempt to identify those who were responsible for the incredibly violent crime but it was decided by authorities that the case would not be solved unless one of those responsible gave themselves or one of their gang members up. An account of the English colony in New South Wales : with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country, compiled, by permission, from the MSS. of Lieutenant-Governor King by David Collins, London: 1798-1802, courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (Q79/60 v. 1, p336)

An account of the English colony in New South Wales : with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country, compiled, by permission, from the MSS. of Lieutenant-Governor King by David Collins, London: 1798-1802, courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (Q79/60 v. 1, p336)

Categories

The Stolen Girls

Five unnamed women who were working as domestic servants in Sydney under the auspices of the 'Aborigines Protection Department', Sydney Mail 24 May 1922, p23 via Trove

Five unnamed women who were working as domestic servants in Sydney under the auspices of the 'Aborigines Protection Department', Sydney Mail 24 May 1922, p23 via Trove

Margaret Tucker at the Aborigines day of mourning, 26 January 1938 (detail), Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (a429004 / Q 059/9)

Margaret Tucker at the Aborigines day of mourning, 26 January 1938 (detail), Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (a429004 / Q 059/9)(Man magazine, March 1938, p108)

Categories