The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Koori Knockout

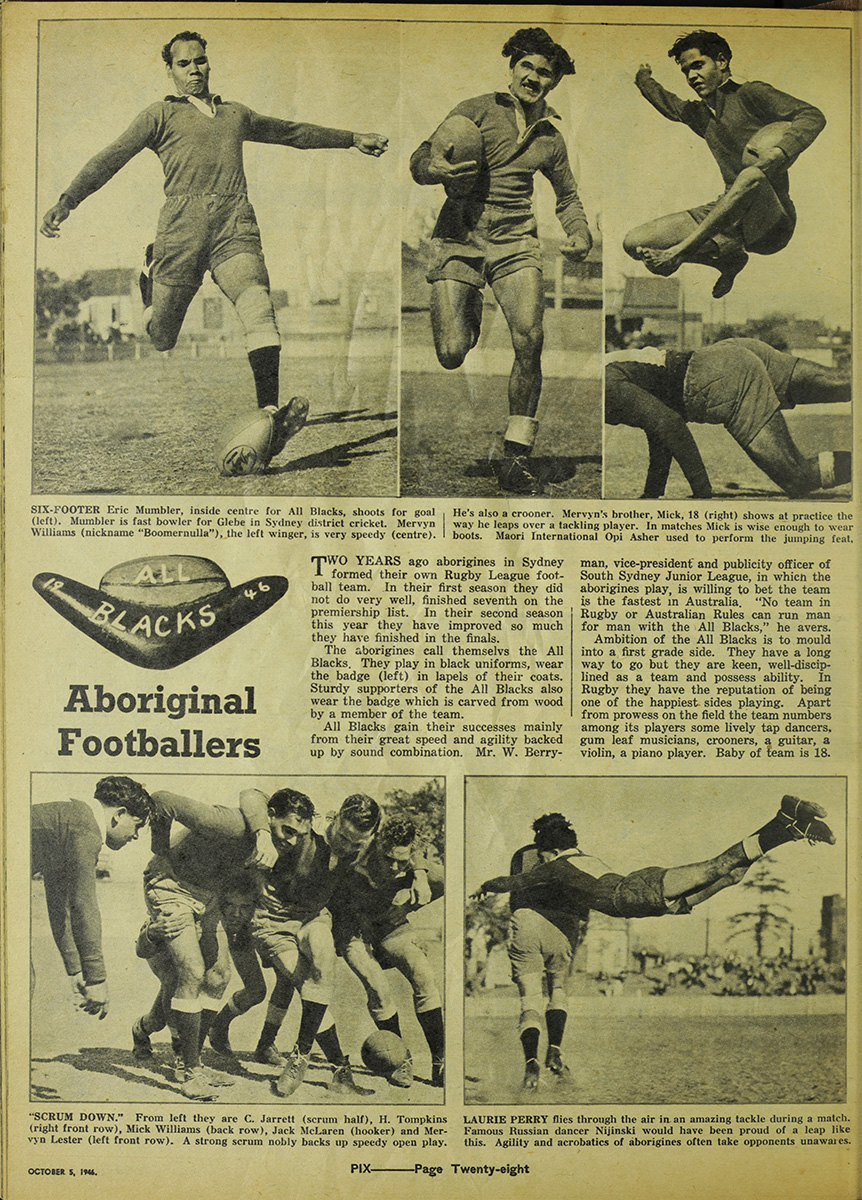

PIX article on the Redfern All Blacks 'Aboriginal Footballers' 1946, PIX, 5 October 1946 p28

PIX article on the Redfern All Blacks 'Aboriginal Footballers' 1946, PIX, 5 October 1946 p28

Listen to Mark and Julia on 2SER here

Aboriginal players in the NRL are some of the best and most recognised players across the competition. They are household names, local, state and national captains. But this has not always been the case, and it was a long road to get here. The NRL as we know it now began in 1908 as a break away competition from the dominate game of rugby union. No known Aboriginal players were amongst the ranks of these first teams, but it was not long before some began to appear around the margins. By 1917 an all Aboriginal team, known as the All Blacks was playing in and around Sydney. They defeated the Port Kembla Rugby League club 13-6 in October that year. As success came, recognition grew and by 1930 in Redfern and 1934 at La Perouse all Aboriginal teams had been established: the Redfern All Blacks and La Perouse All Blacks (1934), later changing to La Perouse United. These teams played against each other, against regional Aboriginal teams and played in the South Sydney District competition against teams in lower and junior grades. In 1952 the first Aboriginal player known to be picked in a First Grade team was Ray Laurie, who played for Balmain. Laurie had been scouted from Casino where he had played for a number of years. In 1951, the year prior to his selection he scored 246 points, including 48 tries and 51 goals. Although he only stayed with Balmain two years, his time was a breakthrough for Aboriginal players. Still despite this the numbers were small and most players were excluded. By the 1960s, as Aboriginal political action grew in Sydney, the All Blacks and other teams became an important component of the community, providing a welcoming community for young men arriving in Sydney from the bush and a measure of pride and success more broadly. Finally in 1971, eight teams including the Redfern All Blacks, La Perouse, Mount Druitt and Koori United which represented Southern Sydney joined four regional teams in the inaugural NSW Aboriginal Rugby League Knockout, now known as the Koori Knockout. PIX article on the Redfern All Blacks 'Aboriginal Footballers' 1946, PIX, 5 October 1946, p29

PIX article on the Redfern All Blacks 'Aboriginal Footballers' 1946, PIX, 5 October 1946, p29

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Julia here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Leigh Straw, Angel of Death Dulcie Markham, Australia’s most beautiful bad woman

Leigh Straw, Angel of Death Dulcie Markham, Australia’s most beautiful bad woman

Leigh Straw, Angel of Death Dulcie Markham, Australia’s most beautiful bad woman

HarperCollins, 2019, ISBN 978073333966 (p/bk), pp1-312, RRP $32.99

Angel of Death is the third book by writer and historian Leigh Straw that focus on Australian women and crime. It follows on from her successful books The Worst Woman in Sydney: The Life and Crimes of Kate Leigh (2016) and Lillian Armfield: How Australia’s First Female Detective Took on Tilly Devine and the Razor Gangs and Changed the Face of the Force (2018). Dulcie Markham (1914-1976) was neither a leading underworld crime boss nor Sydney’s first female detective but as ‘one of Australia’s most popular prostitutes’ she had a place in both their worlds as they fought to control her; Leigh to manage and profit from her work and Armfield to reform her. Dulcie Markham however, had her own agenda and agency. She was deeply fascinated by the power and the profit that organised crime offered and, wanting in on the action, was determined no one was going to stop her. Markham lived much of her working life in the seedy underworlds of Australia’s main cities from the 1920s through to the mid 1950s when she finally retreated into obscure retirement. During these decades she was well known in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane and just for good measure, she had a brief sojourn in Perth in 1946 too. From teenage runaway and streetwalker to professional prostitute, she lived through the audacious flapper days of the Roaring 1920s, the bleak Depression Years of the 1930s and the lucrative era of WW2 when thousands of cashed-up yanks on R and R were in town looking for a good time. She was also a standout beauty and she used her Hollywood looks to lure her punters and to dazzle her lovers - of which she had many. As she herself told newspaper reporters in 1940,‘I was pert, more than ordinarily pretty, and fellows took a lot of notice of me.’But her personal glamour obscured the dark-side, for her life was also firmly ensconced within the criminal, the dangerous and the often very violent. She flew with the crooks and moved with the warring gangs with their razors and pistols, as they fought for control over the illicit drugs, sly grog, prostitution and illegal betting rackets that characterised life in the dubious locales of Australia’s main metropolitan centres. As both prostitute and ‘gangster’s girl’, Straw suggests that ‘jealousy over Dulcie was behind many of the underworld shootings in the 1930s and 1940s.’ Astonishingly, at least a dozen of her lovers and husbands were brutally slashed or fatally gunned down. The first was her beau Cecil ‘Scotty’ McCormack, a 22 year old gang member, who was viciously stabbed through the heart by rivals on the streets of Darlinghurst in May 1931. Dulcie’s appearance at the coronial inquest into his violent death the following month was ‘her first public appearance as a member of Sydney’s underworld.’ Dressed in a racy blood-red dress and hat, with her perfectly coiffured blond hair and ruby lips, there was no escaping her resulting persona; to the city’s pressmen at least, this woman was the classic femme fatale. McCormack’s violent death was the genesis of Dulcie’s long and notorious career, in which her proximity to death and gangland vice was extraordinary. Whether it was sheer coincidence or treacherous collusion on her part, shootouts, showdowns and sly stabbings saw many of the men in her life taken down by the blade or the bullet. By 1940 Dulcie had lost three lovers and a husband to underworld violence, along with numerous close associates and friends. Many more would follow. Coronial inquests and court trials grimly followed all of their deaths - although the criminal code of silence would thwart the legal proceedings. By this time, the newspapers had begun to label ‘Pretty Dulcie’ the ‘Angel of Death’ and ‘Australia’s most beautiful bad woman.’ Tough, streetwise, always alert and constantly on guard, sometimes she used violence herself. Dulcie spent much of her time evading the authorities by using aliases, hair dyes and flitting between cities, or as she herself remarked, she ‘went into smoke’ - although not always successfully. She was arrested and fined on numerous occasions and also did a few stints in Long Bay Prison for vagrancy (streetwalking), prostitution, being ‘idle and disorderly’, and consorting with criminals.By the late 1940s she was living in St Kilda, Victoria, working as a prostitute and also running her house as a sly grog shop and a safe haven for Melbourne’s violent thugs and crooks. Yet the underworld was far from discerning when it came to deal with its rivals - male or female. In September 1951, Dulcie was shot three times in the leg and hip in the front room of her house. She survived, but the wounds crippled her for life. Her young lover at the time, twenty-two-year old Gavan Walsh was shot dead and his brother Desmond was wounded. Later, in 1955 she was found with severe injuries in Bondi, New South Wales. It is highly likely that she had been thrown off a twenty-foot high balcony for some sort of payback from a rival gang, although, ever the ‘moll’, Dulcie kept completely quiet. She simply insisted that she had fallen down the stairs. Yet the terrifying episode made her think deeply about her unsavoury, and potentially fatal, lifestyle, and in the mid 1950s she made her retreat and retired. By this time she had clocked up almost 100 convictions across four cities and had become ‘one of the most famous criminals to walk through Australia’s courtrooms.’ Her final years were spent quietly in domestic bliss in Bondi, married to sailor Martin Rooney who was, by all accounts, a law-abiding man. In many ways however, her death in April 1976 reflected the violence that had characterised much of her life. The once infamous ‘Angel of Death’ burnt to death in a fire which engulfed her Bondi bedroom after she had been smoking in bed. Readers au fait with the criminal history of twentieth century Sydney and Melbourne, will be familiar with many of the people included in this new book. From the notorious female criminal entrepreneurs Tilly Devine and Kate Leigh, to gangsters Guido Calletti, Frank Green and Leslie ‘Squizzy’ Taylor, it is certainly a book with a colourful cast and Straw knows them and the streetscapes and locales they once inhabited remarkably well. Into this picture, she skilfully weaves Dulcie Markham through their interconnected webs of crime, corruption and murderous violence. For readers new to the history of this appalling yet enthralling era of organised crime, the book will simply astonish. But was Dulcie Markham a femme fatale? An Angel of Death? Did she deliberately lead her lovers into dangerous and deadly situations as the press so often suggested at the time? Probably not if the criminal code of violence, silence and pay back is anything to judge by. And after all, these men were already on the wrong side of the tracks. One of the main strengths of the book is that Straw leaves the reader to come to their own conclusions about Dulcie Markham. And there are indeed many silences in her story too – what happened to a daughter supposedly born in 1942? What sort of birth control did Dulcie use during her working life? Did she in fact truly love any of her lovers and husbands or was she simply in it for herself? We don’t get to really know her, despite the rich research materials that the author has mined. Yet the quiet gaps in the historical record in many ways epitomise the life of the Australian underworld itself. Secretive, shadowy and ruled by a criminal code of silence, this was Dulcie Markham’s world. That we don’t get to know her in her entirety is perhaps simply a genuine reflection of this. Dr Catie Gilchrist July 2019 Dr Catie Gilchrist is an historian at the University of Sydney. She has written for the Dictionary of Sydney and the St John's Cemetery project, and is the author of Murder, Misadventure and Miserable Ends: Tales from a Colonial Coroner's Court (Sydney: HarperCollins 2019) Visit the publisher's website to purchase or to find a sample of the book: https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9780733339660/angel-of-death-dulcie-markham-australias-most-beautiful-bad-woman/

Thar She Blows!

Two whale's teeth scrimshaw c1800s, both depicting whaling scenes, Dixson Collection, State Library of NSW (SAFE/DR 40 / Item a and Item b)

Two whale's teeth scrimshaw c1800s, both depicting whaling scenes, Dixson Collection, State Library of NSW (SAFE/DR 40 / Item a and Item b)

Whaling Station, Mosmans Bay, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV1/54)

Whaling Station, Mosmans Bay, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG SV1/54)

Trade card: J. White. Lamp contractor. The Blazing Star, National Gallery of Australia (Accession No: NGA 86.1488)

Trade card: J. White. Lamp contractor. The Blazing Star, National Gallery of Australia (Accession No: NGA 86.1488)

South Sea Whalers boiling blubber c1876 by Oswald Walters B Brierly, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales (DG 366)

South Sea Whalers boiling blubber c1876 by Oswald Walters B Brierly, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales (DG 366)

Whale off Manly November 12, 2011 by Christopher Eden (via Flickr) (CC BY 2.0)

Whale off Manly November 12, 2011 by Christopher Eden (via Flickr) (CC BY 2.0)

Australia's first serial killer

Frank Butler, alias Frank Harwood, alias Frank Ash, Darlinghurst Gaol Photographic Description Book 4 May 1897, Pic: State Archives & Records New South Wales (2138_a006_a00603_6061000098r)

Frank Butler, alias Frank Harwood, alias Frank Ash, Darlinghurst Gaol Photographic Description Book 4 May 1897, Pic: State Archives & Records New South Wales (2138_a006_a00603_6061000098r)

Group at Inquest into a Frank Butler victim - Probably Glenbrook, NSW Pic: Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (At Work and Play - 00330)

Group at Inquest into a Frank Butler victim - Probably Glenbrook, NSW Pic: Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (At Work and Play - 00330)

References

An Interview with Butler, Australian Town and Country Journal, 1 May 1897, p32

Berrima, Australasian Chronicle, 28 April 1842, p2

Butler and the Pressman, Kalgoorlie Miner, 24 April 1897, p17

Butler Bill, The Mercury, 23 August 1897, p4

Butler Case, The Australian Star, 20 October 1897, p6

Butler Described, The Evening News, 28 April 1897, p2

Butler’s Return, The Evening News, 23 April 1897, p5

Execution of Frank Butler, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 July 1897, p203

Extradition of Butler, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 August 1897, p5

Foster, Jason K, The Dark Man: Australia’s First Serial Killer, Newport: Big Sky, 2013

Glenbrook Murder, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 June 1897, p3-6

Glenbrook Murders, Weekly Times, 12 December 1896, p20

Pearce, Alexander, A Confession of Murder and Cannibalism 1824, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (ML MSS A 1326)

Personal Items, The Bulletin, 23 January 1897, p13

Pinto, Susan and Paul R. Wilson, No. 25: Serial Murder, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1990

Scerra, Natalie, Serial Crimes in Australia: Investigative Issues and Practice, Doctor of Philosophy: U of Western Sydney, 2009

Travers, Robert, Murder in the Blue Mountains: Being the True Story of Frank Butler One of Australia’s Most Notorious Criminals, Richmond: Hutchinson Australia, 1972

References

An Interview with Butler, Australian Town and Country Journal, 1 May 1897, p32

Berrima, Australasian Chronicle, 28 April 1842, p2

Butler and the Pressman, Kalgoorlie Miner, 24 April 1897, p17

Butler Bill, The Mercury, 23 August 1897, p4

Butler Case, The Australian Star, 20 October 1897, p6

Butler Described, The Evening News, 28 April 1897, p2

Butler’s Return, The Evening News, 23 April 1897, p5

Execution of Frank Butler, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 July 1897, p203

Extradition of Butler, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 August 1897, p5

Foster, Jason K, The Dark Man: Australia’s First Serial Killer, Newport: Big Sky, 2013

Glenbrook Murder, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 June 1897, p3-6

Glenbrook Murders, Weekly Times, 12 December 1896, p20

Pearce, Alexander, A Confession of Murder and Cannibalism 1824, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (ML MSS A 1326)

Personal Items, The Bulletin, 23 January 1897, p13

Pinto, Susan and Paul R. Wilson, No. 25: Serial Murder, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1990

Scerra, Natalie, Serial Crimes in Australia: Investigative Issues and Practice, Doctor of Philosophy: U of Western Sydney, 2009

Travers, Robert, Murder in the Blue Mountains: Being the True Story of Frank Butler One of Australia’s Most Notorious Criminals, Richmond: Hutchinson Australia, 1972The Last Snake Man of La Perouse

Dancer Paula Pratt and snake expert George Cann at La Perouse 1947, PIX, 22 February 1947, p8

Dancer Paula Pratt and snake expert George Cann at La Perouse 1947, PIX, 22 February 1947, p8

Listen to Minna and Tess on 2SER here

For just over 100 years, down at the ‘La Pa Loop’ snake men could be seen draped in Australia’s deadliest creatures; red bellied black snakes writhing over their shoulders, the head of a black Tiger snake inside their mouth and venomous fangs sunk into the flesh of their cheek. The most well known was George Cann who became a fixture in La Perouse for 45 years. George was born in Newtown rather than La Perouse but he roamed the coastline as a child and got to know a local character called ‘Snakey George.’ Together they would wander through the bush and collect specimens. By 12 years old, George Cann had captured his first Red-bellied Black Snake and set up his first snake show in Hatte’s Arcade, Newtown. At 16 years old George was travelling the carnival and show circuit from Hobart to north Queensland. A show required more than just one hook for the audience so George learnt juggling and trick rifle shooting as well. World War One intervened and took George far into the fields of Western France, where he survived several mustard gas attacks. But on his return to Australia he saw Snakey George who suggested he take over the vacant pitch at the La Perouse loop for snake shows. He continued to tour Australia and soon met and married Essie Bradley, a young snake-woman, who had herself been entertaining crowds as ‘Cleopatra’ from 13 years old and had successfully avoided ever getting bitten. George Cann, eyeball to eyeball with a black snake at La Perouse 5 September 1934 , by Ted Hood, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away - 392)

George Cann, eyeball to eyeball with a black snake at La Perouse 5 September 1934 , by Ted Hood, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away - 392)

High rise living

Wyoming Chambers, Sydney's newest skyscraper 1911, Building Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 45 (12 May, 1911). p45 via Trove

Wyoming Chambers, Sydney's newest skyscraper 1911, Building Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 45 (12 May, 1911). p45 via Trove

Listen to Mark and Tess on 2SER here

Curiously, the first apartment blocks in Sydney were built not so much as space savers but as time savers. The decline in the number of women working in domestic service from the 1890s onwards, made looking after large mansions in Sydney increasingly difficult and expensive. Modern flats or apartments could be kept easily and cheaply; they were self-contained homes in miniature. The first purpose-built flat building in Sydney was The Albany, completed in Macquarie Street in 1905, combining medical and dental chambers on the first two floors and then five stories of residential apartments above. The buildings proximity to the Parliament, Macquarie Street doctors and the law courts meant that it attracted an elite range of residents including Sir Samuel Griffith, Chief Justice of the newly formed Supreme Court of Australia. The Albany was soon joined by others along Macquarie Street and nearby city addresses, the sole survivor from this first phase being Wyoming completed in 1909. One of its selling points was hot water to all flats. In Potts Point Kingsclere (1912) boasted a lift, electricity to all apartments and an internal intercom known as the 'telephonette'. Apartments were soon adopted for public and affordable housing (as we call it now) with the first public housing flats, Strickland Flats in Chippendale, completed by Sydney City Council in 1914. The boom in apartment construction came through the 1920s and 1930s. Modern art-deco apartments rose over the heights of Darlinghurst and Kings Cross and apartments such as The Astor (1923) in Macquarie St became hot property, while at the same time public housing was built throughout Waterloo, Pyrmont, Alexandria and Erskineville. Heading west and south, flats followed the railway lines into the growing commuter suburbs. Finding a flat, Kings Cross, March 1940 by Alec Iverson, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (ACP Magazines Photographic Archive ON 388/Box 025/Item 087)

Finding a flat, Kings Cross, March 1940 by Alec Iverson, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (ACP Magazines Photographic Archive ON 388/Box 025/Item 087)

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay

James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay

James Dunk, Bedlam at Botany Bay

NewSouth Books, 2019, 244 pp. (plus notes, select bibliography and index), ISBN: 9781742236179, p/bk, AUS$34.99

Looking at the great corpus of works that exist on Australia's colonial history, there are so many available to inspire (and inflame) readers that it would be easy to assume that the colonial-focused archives documenting New South Wales have been exhausted. Yet, new interpretations of these records can still rattle some of our assumptions. Such narratives are invitations to look differently, or much more closely, at the past. There are books that we cannot imagine not having access to, like Grace Karskens’ 2009 work The Colony, and those that pick up a particular thread and pursue it relentlessly, for example Meredith Lake’s The Bible in Australia from 2018: books that not only allow us to know our past but are essential in helping us to understand that past. The archives have been cajoled into giving the careful investigator something new. James Dunk’s new book, Bedlam at Botany Bay, is an excellent addition to this list. The matter of madness has certainly not been ignored by previous scholars but Dunk has taken on this important topic and delivered a text of scale and scope that compels us to review the role of madness in colonial Sydney. “Madness is a beguiling and bewildering idea clothed in an expansive and unwieldly word” (p. 5). The archive, clearly, has many more stories to share. Indeed, as Dunk writes: “If we slow down […] and listen closely we find that doubt, anxiety, grief, and despair intrude into these familiar stories. Some became irrational and could no longer govern themselves, or be governed by others. They erupted in mania, or lost themselves in memories and delusions. They cried in fury and tore at the walls of their cells, or stared slack-eyed into the distance” (p. 2). The trauma of mental illness—for the sufferer, their families, their business partners and their workmates as well as for the budding society, including the men responsible for law and order—could be hidden behind closed doors or on full display in the public arena. This suffering was also unpacked in graphic detail at Commissions of Lunacy, basically a trial in which a person was “examined for lunacy or idiocy” (p. 57). The afflictions of such illnesses have long-lasting and wide-ranging ramifications. In colonial Sydney one of the more obvious impacts was reflected in the question: who would pay? Someone needed to cover the costs of repatriating madness back to its point of origin or in facilitating local incarceration of some type. Conversations of professional and sympathetic care were had but administrative ambitions and cash available were rarely in neat alignment. Madness can be mildly disruptive or absolutely brutal, and this is a difficult issue to address either up close or from a distance. To his great credit, Dunk has produced an extraordinary book that offers sufficient light on the subjects within Bedlam at Botany Bay to disrupt the confused and ever-darkening shadows that are generated by madness. One way in which Dunk has made these complex stories accessible is his choice to present his research as a suite of essays, allowing the text to be read as presented or out of sequence. The prose is exceptional. There is a clarity of expression that allows the reader to engage deeply with the chaos that is so central to our conceptions of madness, but also to sit to one side and review the interactions madness has with family and society, with medicine and the law as well as with the economics and politics that are so essential to the storytelling of Sydney. There is also a sense of the conversational as Dunk routinely cites the observations and research of others in a way that introduces a great number of scholars into the text (instead of being relegated to an endnote). This works well and really serves to orientate the reader with the archival voices, the work of various historians and Dunk’s analysis all easily distinguished. This multitude asserts an important truth: madness was, and remains, an issue for all of us. There are extensive notes and a solid index. There are, unfortunately, a few copyediting errors and these will distract some readers. My only genuine complaint about Dunk’s work is that it is too short. More essays on different aspects of madness and those who were, obviously, mad but also incredibly influential during Sydney’s formative years. For example, Robert Lowe and John Knatchbull challenged commonly held ideas about madness in 1844, when Knatchbull killed a Sydney shopkeeper with a tomahawk and Lowe based his client’s defence on the concept of moral insanity (the great lawyer’s initiative failed and the murderer met the hangman). There will, hopefully, be more scholarship from Dunk on this topic for madness “is a subject which never loses its relevance because these fault lines still run around us like scars, the outward signs of an endemic disorder which reaches not only down into the belly of who we are but back into the paths we followed to get here” (p. 8). Bedlam at Botany Bay will comfortably share shelf space with the classic Australian histories that we all (re)turn to. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, June 2019 Visit the publisher's website: https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/bedlam-botany-bay/On your bike!

Madame Franzina, bicycle performer 1876 , courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 362/v3/28r)

Madame Franzina, bicycle performer 1876 , courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 362/v3/28r)

Listen to the whole conversation with Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

On the right is a studio photograph from the State Library's collections of Madame Adela Franzini (or Franzina), a bicycle performer, that was taken in 1876. Madame Franzini travelled widely on the colonial theatrical circuit, appearing in Sydney and other centres around the country from the 1870s to 1890s. A reviewer in a New Zealand paper in 1876 said the bicycle she used was 'of the ordinary description, except that the wheels are toed with indiarubber bands so as to prevent rattle or noise'. They also pointed out that: 'We need hardly say that she rides on one side, and therefore only uses one foot with which to propel the lever'.[1] Her ladylike riding style not withstanding, her appearance in Ballarat in the same year caused 'a sensation among a certain section of the Ballarat clergymen'.[2] Another review of her theatrical appearance in Calcutta in 1890 was also very enthusiastic: 'The most striking feature of the performance given in the Theatre Royal (in Calcutta) on Saturday (March 1) night consisted in the feat of Madame Franzini on the bicycle. The lady is by no means a stranger to Calcutta, having made her appearance some years ago in one of the circuses, but since then she has reached the height of perfection as a bicyclist. The feats she executes are astonishing, especially when we consider her weight and the dexterity required to manipulate the machine in the performance of difficult and fantastic evolutions. The best item in the programme, which as far as her portion goes was far too short, was her circling through a maze of lighted bottles without touching one or being in the least inconvenienced by the serried flames.'[3] Henri L'Estrange, The Australian Blondin 1876 by George Willetts, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria (H96.160/2603)

Henri L'Estrange, The Australian Blondin 1876 by George Willetts, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria (H96.160/2603)

Final heat of the Grand Bicycle Steeplechase - the water jump. Anniversary Day sports at the Albert Ground, Redfern 26 January 1870, Illustrated Sydney News, 17 February 1870 p344

Final heat of the Grand Bicycle Steeplechase - the water jump. Anniversary Day sports at the Albert Ground, Redfern 26 January 1870, Illustrated Sydney News, 17 February 1870 p344

Norman Selfe (with beard) and Edmund Wolstenhome on velocipede invented by Selfe c1870s, courtesy of the Deer Family

Norman Selfe (with beard) and Edmund Wolstenhome on velocipede invented by Selfe c1870s, courtesy of the Deer Family

George Street, near the GPO c1900 By Kerry & Co, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (PXA 448, 9)

George Street, near the GPO c1900 By Kerry & Co, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (PXA 448, 9)

Billie Samuels at Martin Place on the Malvern Star bike before riding to Melbourne, 4 July 1934, by Sam Hood, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away - 4237)

Billie Samuels at Martin Place on the Malvern Star bike before riding to Melbourne, 4 July 1934, by Sam Hood, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Home and Away - 4237)

Edward Smith Hall and The Monitor

Edward Smith Hall, 1852, by Charles Rodius, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (P2/7)

Edward Smith Hall, 1852, by Charles Rodius, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (P2/7)

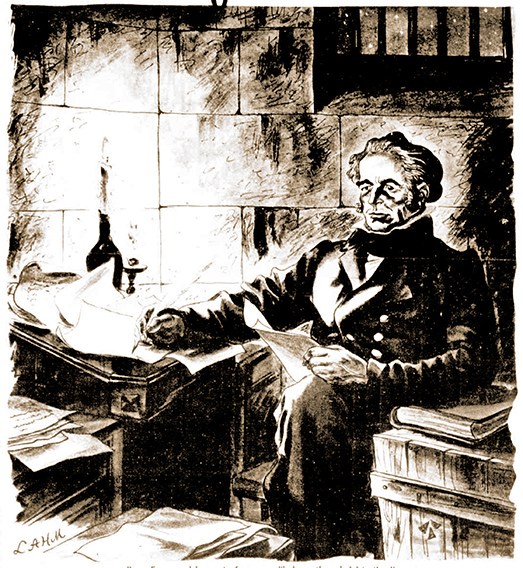

A 1940s depiction of Edward Smith Hall writing in his gaol cell, The Sun, 13 June 1948, p7 via Trove

A 1940s depiction of Edward Smith Hall writing in his gaol cell, The Sun, 13 June 1948, p7 via Trove

The Monitor, 19 May 1826, via Trove

The Monitor, 19 May 1826, via Trove

Sailors, Spies and Sydney Stairs

Looking down the McElhone Stairs from Victoria Street towards Cowper Wharf Roadway, Woolloomooloo 1960, by Geoff Paton, Courtesy of City of Sydney Archives (SRC21844)

Looking down the McElhone Stairs from Victoria Street towards Cowper Wharf Roadway, Woolloomooloo 1960, by Geoff Paton, Courtesy of City of Sydney Archives (SRC21844)

Listen to the audio of Minna and Tess on 2SER here

The hive of human activity on these stairs over the decades has inspired artists, writers and filmmakers to try and distill its essence. In 1944, Sali Herman won the Wynne Prize for his landscape painting which was swept up in the ‘drama of a formidable staircase [and] how it can diminish human scale’ 1 while John Olsen tried to capture the ‘the urban pulse of the steps as a transitional zone where sailors, soldiers and drunks made their way to the bright lights of Kings Cross’.2 However perhaps one of the most intriguing uses of the stairway was its role in a Cold War espionage case. In 1962 Ivan Fedorovich Skripov, First Secretary of the Russian Embassy in Australia, concealed an aluminium message container in one of the balustrades. It was meant to be collected by another operative ‘Sylvia’. Skripov had already used other Sydney public spaces to plant messages for her, including at a water meter under Sydney Harbour Bridge and a grave in one of Sydney’s cemeteries. Written with invisible ink, the messages had to be developed using a solution based on chemical crystals contained in pill capsules. Copies of the messages leading to the McElhone Stairs are held in the National Archives, with one reading: "Glad to have your answer in time. Urgently need your help. Please collect container on the first landing of the McElhone Stairs on the way from Victoria Street to Cowper Wharf Road, Woollomooloo (Repeat – McElhone Stairs)."

Developed secret writing on reverse side of letter dated 17th September, 1962 that was given to ASIO agent by Ivan Fedorovich Skripov, First Secretary, Russian embassy , courtesy of National Archives of Australia (A432, 1963/2272, Photo 11A, Barcode: 8162303)