The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Joy McCann, Wild Sea: A History of the Southern Ocean

Joy McCann, Wild Sea: A History of the Southern Ocean.

Joy McCann, Wild Sea: A History of the Southern Ocean.

NewSouth Books (2018), 256pp., ISBN 9781742235738, p/bk, RRP: $32.99

The Southern Ocean, the world’s least known and least visited ocean, is the only ocean which flows completely around the earth, unimpeded by any significant landmass. It stretches north from Antarctica to the southern coastlines of Australia, New Zealand, South America and South Africa. Australian environmental and social historian Joy McCann’s history of this spectacular and often mysterious and threatening feature of our planet is both informative and impressive. McCann’s wide-ranging research is presented in clear and often vivid prose which conveys her love and respect for her subject. This is more than a history of the Ocean, drawn from scientific investigations and explorers’ accounts. It is a fascinating celebration of what the Ocean means to the earth and a call for careful attention to the threats faced by those who depend upon it, especially its inhabitants from tiny krill to the majestic whale and albatross. Having sailed through the Southern Ocean and stepped ashore on some of its most forbidding coasts, Joy McCann is no armchair traveller. She brings a personal knowledge and commitment to her task of describing, interpreting and stirring up enthusiasm for this vast and wondrous ocean. The book is well indexed and is also illustrated by a good selection of drawings and photographs. There are also four very useful maps which readers will often need to consult as they journey with the author, though it is unfortunate that the locations of these maps were not given on the Contents page. Dr Neil Radford, June 2018 Visit the NewSouth Books website: https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/wild-sea/Categories

The Bogle-Chandler mystery

The Canberra Times, 10 May 1963, p3 via Trove

The Canberra Times, 10 May 1963, p3 via Trove

- Cameron Hazlehurst, Bogle, Gilbert Stanley (1924–1963) Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1993, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bogle-gilbert-stanley-9534

- Geoffrey Chandler, So You Think I Did It, Sydney: Sun Books, 1969

- Who Killed Dr Bogle and Mrs Chandler?, Film Australia in association with Blackwattle Films, 2006

- DR. BOGLE AND MRS CHANDLER - DID HYDROGEN SULPHIDE REALLY KILL THEM? ABC Catalyst Story Archive, 23 November 2006, http://www.abc.net.au/catalyst/stories/s1795448.htm

- Peter Butt, Who Killed Dr Bogle and Mrs Chandler?, Sydney: New Holland, 2012

- Who Killed Dr Bogle and Mrs Chandler? (2006), Australian Screen Online https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/who-killed-dr-bogle/

- Tracey Bowden,Two women may hold answer to how Dr Gilbert Bogle and Margaret Chandler died in 1963, ABC News, 2 September 2016: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-02/two-women-may-hold-answer-to-bogle-chandler-case/7808820

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing funding and needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

Categories

Jane Lydon and Lyndall Ryan (eds), Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre

Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre, edited by Jane Lydon and Lyndall Ryan

Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre, edited by Jane Lydon and Lyndall Ryan

NewSouth Books, 215 pp., ISBN: 9781742235752, p/bk, RRP AUS$34.99

On 10 June 1838 twelve men, “in an unprovoked act of violent terror” (p. xi), committed an atrocity known today as the Myall Creek Massacre. The massacre — which saw the brutal and senseless murder of Aboriginal men, women and children in northern New South Wales — has left deep scars upon many communities. To mark the 180th anniversary of this crime, scholars Jane Lydon and Lyndall Ryan have brought together Remembering The Myall Creek Massacre. The foreword by Sue Blacklock and John Brown notes a hope that “this ongoing focus on the massacre, and the trial that followed, may drag us towards a more honest understanding of our history, and the possibility of more just and open acknowledgement of our tangled journey in Australian over the past two centuries” (p xiii). Some of the essays in the book consider individuals connected with the crime. Lyndall Ryan looks critically at Henry Dangar, a wealthy landowner with holdings that included the Myall Creek area, and his actions during the aftermath, which included attempts to discredit a key witness and providing financial support to secure counsel for the defence. Patsy Withycombe takes on the difficult task of investigating John Henry Fleming, the ringleader of the Myall Creek massacre (p 38). Other contributors have looked at some of the responses to the massacre in the media at the time. Jane Lydon explores depictions of the events at Myall Creek and how “a handful of visual images gave form to debates around violence on the colonial frontier, arousing emotions and directing viewers how to see this distant tragedy” (p 52) while Anna Johnston elegantly unpacks Eliza Hamilton Dunlop’s poignant response to the massacre in the poem “The Aboriginal Mother” which was published in the Australian on 13 December 1838, “only days before the public execution” of the men found guilty of murder (p 68). Lyndall Ryan works to contextualise the massacre by looking at some of the many other examples of frontier violence in the nineteenth century. Iain Davidson, Heather Burke, Lynley A. Wallis, Bryce Barker, Elizabeth Hatte and Noelene Cole, in a collaborative effort, connect the massacre at Myall Creek and the people of Wonomo, suggesting it was likely that other Aboriginal communities “were forewarned by oral testimony of the impending struggle and met it with active and passive resistance” (p 110). John Maynard offers a powerful personal reflection and memoir of his “own journey to Myall Creek in 2015” (p 111). Jessica Neath and Brook Andrew talk about how in “Australia, we walk on bones” reminding us that “the Myall Creek massacre was only one of the countless massacres of the Frontier Wars right across Australia” (p 131). Their work, presented through conversations, highlights the importance of memorials and argues for the “greater visibility” of the Frontier Wars and their ongoing legacy in Australia. An afterword comes from the always elegant pen of Mark Tedeschi. The text includes maps, examples of visual culture, a bibliography, extensive endnotes and an index. This volume is a work about trauma and the deep pain that continues to be felt by so many today. Remembering The Myall Creek Massacre is difficult but essential reading. It offers accounts of a crime that has become one of the symbols of so many crimes that have been committed against Aboriginal Australians. For non-Indigenous Australians this work offers an important opportunity for reflection and, by extension, a level of understanding that can assist in facilitating a more reconciled future. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, June 2018 Visit the NewSouth Books website https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/remembering-myall-creek-massacre/Categories

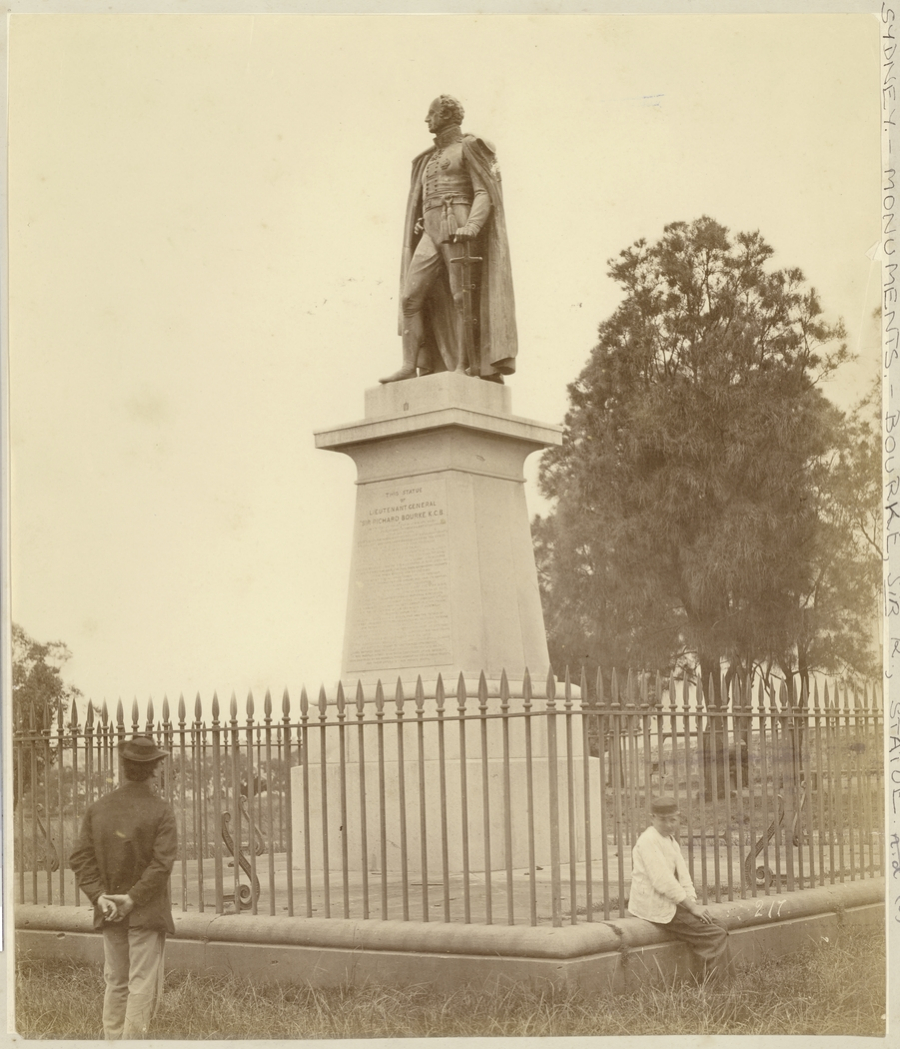

Australia’s first public sculpture: Richard Bourke

Governor Bourke's statue, Domain 1871, by Charles Pickering, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SPF/1056)

Governor Bourke's statue, Domain 1871, by Charles Pickering, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SPF/1056)

The Sun, 19 March 1925, p12 via Trove

The Sun, 19 March 1925, p12 via Trove

Categories

Hazel Baron and Janet Fife-Yeomans; My Mother, A Serial Killer

Hazel Baron and Janet Fife-Yeomans, My Mother, A Serial Killer

Hazel Baron and Janet Fife-Yeomans, My Mother, A Serial Killer

HarperCollins Australia Publishers, 239 pp., ISBN: 9781460754528, p/bk, AUS$32.99

Hazel Baron, the daughter of convicted murderer Dulcie Bodsworth, collaborated with journalist Janet Fife-Yeomans to tell her story in My Mother, A Serial Killer (2018). There were two sides to Dulcie Bodsworth. There was the caring and kind woman everyone enjoyed spending time with, and there was the cold, manipulative woman who was determined to have her own way, even if that meant committing murder. Dulcie’s daughter, Hazel, knew the awful truth. Hazel first suspected her mother was a murderer when she was only nine years old. After three murders, including the murder of Hazel’s father, Ted Baron, in Mildura in 1950 and two men in Wilcannia in 1956 and 1958, Dulcie and her husband Henry Bodsworth, were finally charged in December 1964. “The truth wasn’t always nice but it was always the truth. The truth was that it was Hazel who had dobbed her mother in. The truth was that she knew her mother would have kept on killing if she had not been caught” (p. 11). It is easy to dismiss difficult family relationships with observations that “all families are complicated in their own way”. Hazel’s story makes it clear that some are far more complicated than others. This is a story of three victims, of a daughter tipping off the police, of the co-accused, of traumatic days in a courtroom, of sentencing and (for Dulcie) of thirteen and a half years behind prison bars were she would inspire the creation of the “mischievous lovable old lag, Lizzie Birdsworth” (p. 218) in the popular television series Prisoner (1979-1986). Dulcie would even sit with one of the writers from Grundy, advising on prison life and prison slang, giving “herself the grand-sounding title of ‘consultant’ to the production” (p. 222). The impact that a parent can have on their children, and that “even though [Hazel and her brother Allan] were adults, Dulcie could still both rule and ruin their lives” (p. 179), is clear throughout the text. Indeed, years after Dulcie’s death in Sydney in 2008 her influence is still keenly felt by those who were close to her. There is within this book a story of strained forgiveness. When Fife Yeomans asks Hazel how “she could have had anything to do with her mother after Dulcie had murdered Hazel’s father, Hazel had an answer that summed up, as only she could, her relationship with Dulcie: I don’t hate her; I don’t even dislike her. She was like a neighbour and I did the right thing by her” (p. 237). My Mother, A Serial Killer is a fascinating story, neatly told. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, May 2018 For a preview of the book or to purchase online, visit the HarperCollins Australia website: https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9781460754528/my-mother-a-serial-killer/Categories

The Bridge Street Affray: an incident that changed policing in New South Wales

Sydney Morning Herald, 3 February 1894, p9

Sydney Morning Herald, 3 February 1894, p9

Listen to Rachel and Tess on 2SER here.

In the very early morning of Friday 2 February 1894, three men were trying to break into a safe at the Union Steamship Company offices in Bridge Street in the city. They were probably disturbed by the night watchman doing his rounds who had noticed something amiss and was consulting with a policeman on his beat, and they rather rapidly left the building before completing the job. Three other policemen in the area noticed them leaving and thinking it looked suspicious, gave chase. The robbers used their jemmies, or crowbars, to attack the officers, knocking two unconscious and threatening the third, Senior Constable Ball, with a gun. The thieves ran. One, who was never charged, sensibly ran towards the Domain. The other two, Charles Montgomery and Thomas Williams, had only recently arrived in Sydney (they'd been in Pentridge Prison in Melbourne before that), and they ran down Phillip Street towards what we now think of as the Police and Justice Museum, but which was then the Water Police Station and Court. Senior Constable Ball was, meanwhile, shouting for reinforcements, who, of course, poured out of the Water Police Station which the two escaping thieves were running towards. There was another fight as the police tried to arrest them and three more police officers were seriously injured before Montgomery and Williams were finally incarcerated. You can also hear Rachel talking about crime writing with Meg Kenneally and Dave Warner next Monday in the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts Mystery & Crime Festival. See the SMSA website for further details: https://smsa.org.au/events/event/deadly-words-crime-writing-essentials-panel/

Listen to the podcast with Rachel & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing funding and needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!

You can also hear Rachel talking about crime writing with Meg Kenneally and Dave Warner next Monday in the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts Mystery & Crime Festival. See the SMSA website for further details: https://smsa.org.au/events/event/deadly-words-crime-writing-essentials-panel/

Listen to the podcast with Rachel & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing funding and needs your help. Make a donation to the Dictionary of Sydney and claim a tax deduction!Categories

The Shaftesbury Reformatory in Vaucluse

Shaftesbury, Vaucluse c1925 by EG Shaw, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (a7806 Online, 2)

Shaftesbury, Vaucluse c1925 by EG Shaw, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (a7806 Online, 2)

Listen to Nicole and Tess on 2SER here.

After several reports were made in the 1870s on the inadequacy of Biloela, the girls’ reformatory on Cockatoo Island, the New South Wales government needed to find an alternative location that wouldn’t have Biloela’s ‘dry, stony prison aspect’. The site at Vaucluse was selected because it occupied ‘a position which, for a charming outlook on either hand and for healthfulness, could not be surpassed‘ . The Shaftesbury Reformatory opened in 1880 in an old hotel building that had been converted for the purpose. The Reformatory functioned as an alternative to prison for girls aged under 16 who were convicted of criminal offences, and eventually comprised a series of cottages and three solitary cells surrounded by high fences. It usually housed up to 20 girls for one to five years. On its opening in 1880, the Sydney Morning Herald said: ..every part of the building have been designed in the most approved manner; and while throughout there is the unmistakable aspect of a place where the inmates are forcibly detained, there are many things about the style of construction and the fittings of the different compartments which give a more than ordinarily cheerful appearance to everything, and doubtless will have a very beneficial effect in the reformation of the girls. Girls were sent to the Shaftesbury Reformatory for a range of offences and for varying lengths of time: 14 year old Emily Miller was sentenced to 14 days in 1882 for stealing a diamond ring from her master; Alice Bambilliski was sentenced to two years in 1890 for stealing 25 pounds from the Kogarah Post Office; and Annie Andrews, aged 15, was sentenced to two years and four months in 1897 for being an ‘idle and disorderly person’. Detail of 1890s map of Woollahra showing Shaftesbury Reformatory and lighthouse at South Head, Vaucluse, courtesy National Library of Australia (MAP RaA 39, p43)

Detail of 1890s map of Woollahra showing Shaftesbury Reformatory and lighthouse at South Head, Vaucluse, courtesy National Library of Australia (MAP RaA 39, p43)

Categories

Michelle Scott Tucker, Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World

Michelle Scott Tucker, Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World

Michelle Scott Tucker, Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World

Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2018, ISBN 9781925603422, pp 1-386, RRP $32.99

Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World is the author’s first book. And what a fabulous triumph it is. Well researched and richly absorbing, this is the remarkable story of Australia’s first free female European to settle in colonial New South Wales. Expansive, engaging and utterly engrossing the fascinating life of one brave pioneer woman is here explored with lovely attention to detail. The reader is transported into her world with such vivid intensity, it is almost as if you are right there, standing by Elizabeth’s side and willing her on through all her trials and tribulations. Of which, during her long and interesting life, there were many. It is also a timely book. Hazel King’s Elizabeth Macarthur and her World was published back in 1980 whilst Lennard Bickel’s Australia’s First Lady:The Story of Elizabeth Macarthur followed later in 1991. It was time for a fresh telling and the author is to be congratulated for doing it with such aplomb. Elizabeth Macarthur arrived in the colony with her husband John and young son Edward in 1790. She died here in 1850 on the eve on the gold rushes when the colony was a very different place indeed. During those sixty years, she was a loving wife and mother, entrepreneur, worker, farmer, businesswoman, sheep expert, gardener, homemaker, teacher and nurse. She worked damn bloody hard for much of her long life and she was also the peacemaker, the wise matriarch and the central key to the family’s subsequent success. Like a solid English oak firmly planted in the wilds of the Camden Park area. Elizabeth was also a prolific journal and letter writer, and she penned realms of regular correspondence to her friends and family back in England. Those that survive are housed in the collection of Macarthur Papers in the Mitchell Library in the State Library of New South Wales, together with diaries, journals, ledgers and account books. The author skilfully weaves them throughout the book to let us hear Elizabeth speak. The Macarthurs travelled as part of the Second Fleet and the author vividly captures the sheer terror of the long voyage for a young genteel lady who was heavily pregnant with her second child. Tucker also reminds us of the utterly abysmal conditions of the convicts stowed, starved, and chained below decks, as the tempestuous Southern Ocean slowly rolled them all towards the fledgling colony at the edge of the world. Over a quarter of the convicts sent out in the Second Fleet did not survive the journey. It was a scandalous state of affairs and it might have been avoided. Starvation and scurvy, disease and dysentery wasted many away. Neither did Elizabeth’s first born daughter survive. She too died at sea, soon after birth. Seven more children would bless the Macarthurs' long marriage of forty-five years, and so commence a dynasty. Along the way, the book includes the horrors of frontier violence, the politics of colonial society and the convict era, the vagaries of snobbish genteel ladies and the propensity of their husbands (including her own) to duel to resolve their gentlemanly disputes, the rum rebellion and the overthrow of Governor Bligh. But that is all in the background. This is the story of the making of a family dynasty through good luck, hard work, resilience and family loyalties. It is also the story of the sheer harshness of living in a frontier society for a woman with frequent pregnancies, and a husband frequently absent, either in Sydney or in exile back in Europe, or when he was suffering an episode of the mental disquiet which plagued him throughout his life. But Elizabeth managed. Even when four of her own children very sadly predeceased her. This book is her story of living through all of this and the legacy she left behind for both her family and for the growing young nation itself. There is a select and yet expansive bibliography, endnotes and a comprehensive index. The picture credits are rather brief, although this is merely a small observation rather than a large criticism. A sweeping saga, a soaring family epic, this is an expansive book and takes us from Elizabeth as a new young wife to an aged, beloved and yet still sprightly grandmama aged eighty-three years of age, which in 1850, was a vintage age indeed. It crosses decades and spans continents exploring exile, longing, memories and family ties. This would make for a fabulous television drama. I wanted to weep when Elizabeth died. Not that it was unexpected. But after 328 pages of experiencing this incredible woman, it was like losing a good wise friend. Her remarkable story, albeit of a different time and era, is yet a story which still resonates so deeply today. And ultimately, this is what makes A Life at the Edge of the World such a compelling and unforgettable read. Just gorgeous. Dr Catie Gilchrist May 2018 Available at all good book stores now. Find out more about the book and author on the Text Publishing website here Dr Gilchrist is the State Library of NSW Nancy Keesing Highly Commended Fellow 2018.Categories

What Sick Shark Revealed

Cover of book 'The Shark Arm Case' by Vince Kelly, published by Horwitz Publications 1963, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 343.1/30A1)

Cover of book 'The Shark Arm Case' by Vince Kelly, published by Horwitz Publications 1963, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 343.1/30A1)

Truth (Sydney), 5 May 1935, via Trove

Truth (Sydney), 5 May 1935, via Trove

Categories

The Rum Rebellion and the Madness of Colonial New South Wales

The arrest of Governor Bligh 1808, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a128113 / Safe 4/5)

The arrest of Governor Bligh 1808, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a128113 / Safe 4/5)

John Macarthur, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (a2408002 / DG 222)

John Macarthur, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (a2408002 / DG 222)

Categories