The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company

Bloomsbury, 2019, 522 pp., ISBN: 9781408864388, p/bk, AUS$26.99

Highly-regarded historian William Dalrymple's The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company is a fabulous achievement. There are two epigraphs upfront. 'A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people' (a letter written by Leo Tolstoy in 1908) and 'Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like' (a statement made by Edward, First Baron Thurlow during the impeachment of Warren Hastings). These well-chosen lines invite the reader into an extraordinarily complex history that is brought vividly to life by Dalrymple. Dalrymple’s knowledge of his subject and his engaging writing style realise this volume as something much more than a well-told history with historical figures moving about and doing what they did to force the next historical event. Dalrymple understands this history. He knows these people. This is obvious when he introduces readers to some of the men who are central to this story of corporate ambition and gobsmacking greed. There are the English: Robert Clive is 'violent and ruthless but extremely capable', Warren Hastings is 'plain-living, scholarly, diligent' (p.xiii), Philip Francis is 'scheming' (p.xiv) while Robert Clive’s son, Edward Clive, is just 'notably unintelligent' (p.xv). There are the French. The Mughals, including the 'handsome and talented' Shah Alam (p.xvii), the Nawabs, the Rohillas, the Sultans of Mysore and the Marathas. There are the brave, the brutal, the resigned, the visionary and the incompetent. Dalrymple’s writing is confident and at times mesmerising. He has, too, a knack for selecting just the right piece of information to set the scene. For example, the first line of his introduction notes that one of 'the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: loot' (p.xxiii). His ability to summarise and to easily convey the magnitude of key points makes this work a gripping read. This is, after all, a story unlike any other, for: In many ways the East India Company was a model of commercial efficiency: one hundred years into its history, it had only thirty-five permanent employees in its head office. Nevertheless, that skeleton staff executed a corporate coup unparalleled in history: the military conquest, subjugation and plunder of vast tracts of southern Asia. It almost certainly remains the supreme act of corporate violence in world history. (pp.xxvi-xxvii) The tale begins in 1599 and covers the main events of the rise, and fall, of the East India Company. Driving this history is a thirst for wealth that must be quenched, regardless of the human cost. Processes of colonialism are inevitably traumatic for the peoples being colonised. In India, the terror did not come specifically from another country but from a brand name: as the 'transition to colonialism took place through the mechanism of a [militarised] for-profit corporation, which existed entirely for the purpose of enriching its investors' (p.394). Eventually, 'enough was enough' and the Company was brought to heel by the Parliament and the Crown that had facilitated its establishment and expansion. In the end, the organisation that had wrought so much damage and death would dissolve in a whimper. Its powers curbed, it 'limped on in its amputated form for another fifteen years when its charter expired, finally quietly shutting down in 1874, ‘with less fanfare,’ noted one commentator, ‘than a regional railway bankruptcy’' (p.391). There is a chilling point made in the epilogue: The East India Company, has, thankfully, no exact modern equivalent. Walmart, which is the world’s largest corporation in revenue does not number among its assets a fleet of nuclear submarines; neither Facebook nor Shell possesses regiments of infantry. Yet the East India Company — the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok — was the ultimate model and prototype for many of today’s joint stock corporations. The most powerful among them do not need their own armies: they can rely on governments to protect their interests and bail them out. (p.396) The end of the East India Company is not the end of the story of the corporation. There are maps upfront and a list of the key players with a short biographical note for each. There is also a very useful glossary, beautiful images with credits and a detailed index. The scholarship behind this work is revealed through the notes and bibliography which consumes 89 of the 522 pages of text. Skimming the references it is difficult not to be drawn in, almost hypnotised, by the scale and scope of materials utilised to inform Dalrymple’s work. So many different authors, formats, languages and repositories and, of course, so many documents created by the East India Company. This listing is an invaluable resource for students of history and anyone wanting to do further reading on the organisation that 'probably invented corporate lobbying' (p.xxvii) and at its peak controlled 'almost half the world’s trade' (p.3). The Anarchy is important reading and a timely tale of the raw violence that corporations were once capable of and the levels of power that such enterprises continue to seek. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, October 2019 Visit the publisher's website here.Trim, the Cartographer’s Cat: The Ship’s Cat Who Helped Matthew Flinders Map Australia

Trim, the Cartographer’s Cat: The Ship’s Cat Who Helped Matthew Flinders Map Australia

Trim, the Cartographer’s Cat: The Ship’s Cat Who Helped Matthew Flinders Map Australia

by Matthew Flinders, Philippa Sandall and Gillian Dooley, with illustrations by Ad Long and a foreword by Julian Stockwin

Adlard Coles (Bloomsbury), 2019, 128 pp., ISBN: 9781472967206, h/bk, AUS$22.49

Trim, one of the world’s most famous seafaring cats, sets sail again in Trim, the Cartographer’s Cat. Matthew Flinders is famous for completing the first circumnavigation of the continent that he would call “Australia”. The young naval officer was given instructions, in early 1801, 'to explore in detail, among other places, that part of the south Australian coastline then referred to as ‘the Unknown Coast’, to document its flora and fauna (p.113), and to circumnavigate The Great South Land, which he completed in 1803. Flinders was one of 88 men on board his ship, the HMS Investigator. The crew included Bungaree of the Kuringgai people (custodians of the Broken Bay area, north of Sydney), scientific staff, and Flinders’ faithful furry friend, Trim. The black and white cat lost his life while his master, who had been accused of spying, was incarcerated on Mauritius. Flinders’ grief is palpable in his work A Biographical Tribute to the Memory of Trim (1809), a moving reflection that has been faithfully reproduced in this small book. In this publication the story of Trim, 'the best and most illustrious of his Race' (p.50), benefits from careful footnoting to unpack the various literary allusions and to explain the various nautical terms that Flinders—cartographer and catographer—used in this work. Flinders’ account is supported by an informative essay by Gillian Dooley that offers some context to the story of Trim and looks at not only what the Biographical Tribute reveals about a much-loved companion but what, too, this beautiful snippet of literature reveals about its author. Through this short work, the manuscript of which is only six pages in length (p.11), Flinders 'revealed a side of himself that we wouldn’t otherwise suspect had ever existed' (p.59). There is also a whimsical response 'by Trim' about his 'Seafurring Adventures with Matt Flinders' (p.65), in which the 'Seven Secrets of the Successful Hunter' are shared. These are: 'Be prepared. Plan ahead. Be patient. Persevere. Be fit for the task. Maintain a healthy life balance. Practice makes perfect' (p.81). Most excellent advice. One of the great joys of this edition of Trim’s story is the suite of delightful illustrations by Ad Long. There is a wonderful attention to detail in each drawing, even the page numbers are offered against a background of the silhouette of a cat’s head. There is, too, a good selection of images from a few of the collections that hold resources documenting Flinders’ life and work. There is a useful timeline of Flinders’ major journeys with Trim (pp.111–16). There are also notes, picture credits and a basic index. Trim, The Cartographer’s Cat will slip easily into the paws of readers who enjoy stories of adventure and of friendship. Those who admire the felis catus and their antics—from playing games to stealing food—will surely feel compelled to add this little volume to their book collection. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, October 2019 Visit the publisher's website hereRose Bay Airport

Short Empire Flying Boat Cooee at Rose Bay 5 July 1939, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON 388/Box 035/Item 119, ACP Magazines)

Short Empire Flying Boat Cooee at Rose Bay 5 July 1939, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON 388/Box 035/Item 119, ACP Magazines)

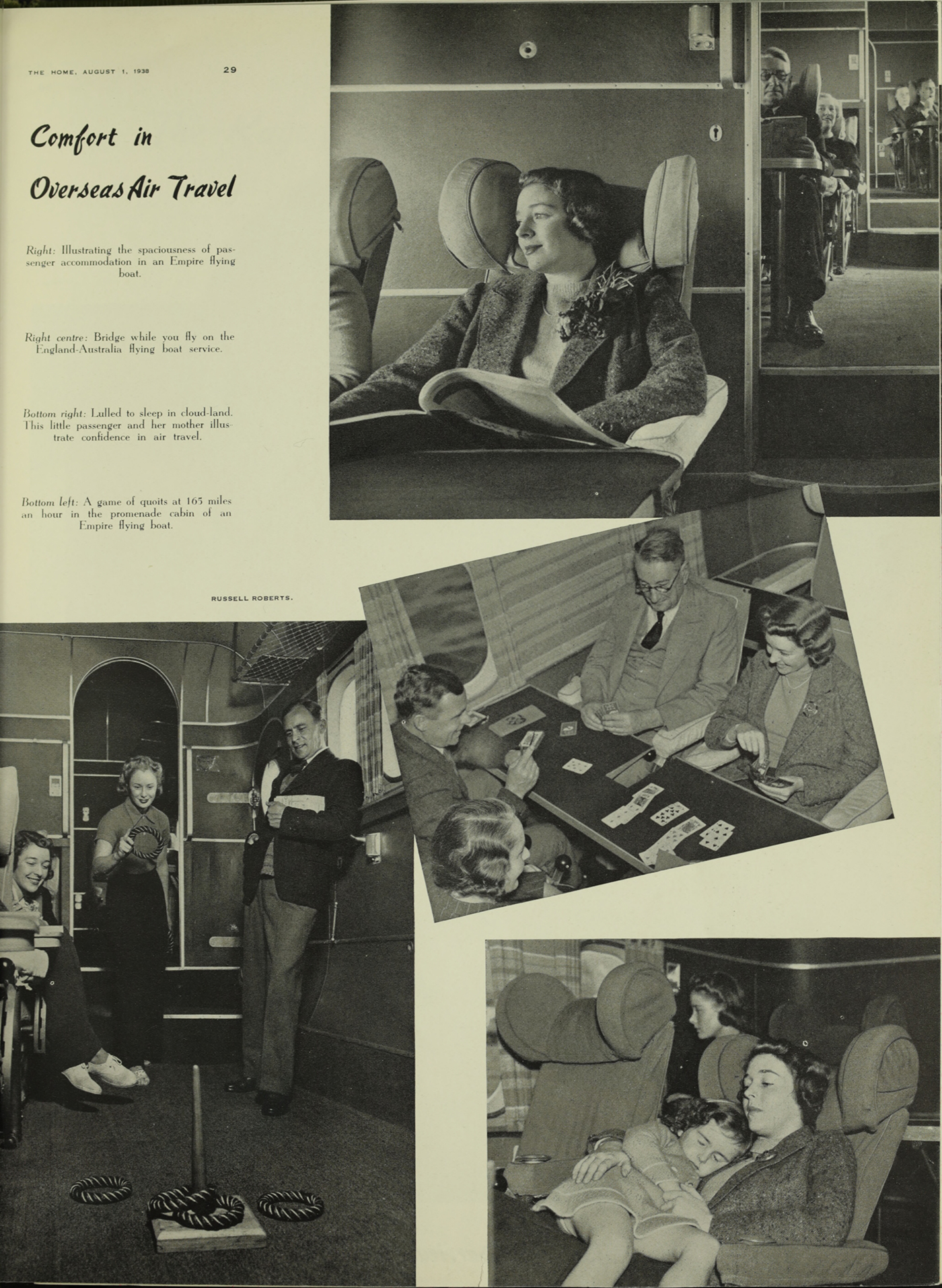

Comfort in Overseas Air Travel, The Home, August 1938, p29

Comfort in Overseas Air Travel, The Home, August 1938, p29

2SER is celebrating it's 40th anniversary this month. ’40 Years of 2SER’, a free interactive exhibition exploring the stations four decades of broadcast will be on at 107 Projects in Redfern from the 10 – 20 October. Head to the 2SER website for further details about the anniversary and the exhibition .

2SER is celebrating it's 40th anniversary this month. ’40 Years of 2SER’, a free interactive exhibition exploring the stations four decades of broadcast will be on at 107 Projects in Redfern from the 10 – 20 October. Head to the 2SER website for further details about the anniversary and the exhibition .

Mark Dunn is the former Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney. Visit the State Library of New South Wales for the 2019 Open Day on Saturday 12 October and enjoy a full day of fun activities, talks and tours for the whole family. Head to the Library website for the full program of events.

Visit the State Library of New South Wales for the 2019 Open Day on Saturday 12 October and enjoy a full day of fun activities, talks and tours for the whole family. Head to the Library website for the full program of events.

The Great Fire of Sydney

Looking down Hosking Place from Castlereagh Street after the Moore Street fire, 1890, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 2127, Box 10, 45)

Looking down Hosking Place from Castlereagh Street after the Moore Street fire, 1890, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXA 2127, Box 10, 45)

Plan of the block burnt, Leader, October 11, 1890 p37 via Trove

Plan of the block burnt, Leader, October 11, 1890 p37 via Trove

Demolition of buildings, Moore Street, 7 October 1890 , courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL PXX 65,77)

Demolition of buildings, Moore Street, 7 October 1890 , courtesy Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL PXX 65,77)

Tom Frame, Gun Control: What Australian Got Right (and Wrong)

Tom Frame, Gun Control: What Australia Got Right (and Wrong)

Tom Frame, Gun Control: What Australia Got Right (and Wrong)

NewSouth Books, 2019, 201 pp., ISBN: 9781742236346, p/bk, AUS$34.99

Professor Tom Frame’s Gun Control: What Australia Got Right (and Wrong) offers a clear and concise history of Australian politics and policy for the period following the Port Arthur massacre in April 1996. This is a story about a gunman who murdered 35 people and injured another 23, a newly-elected Prime Minister, extraordinary collaboration between States and the Commonwealth and the production of the National Firearms Agreement within two weeks of a mass murder at one of Tasmania’s best-known historical sites. This is a story, too, of metropolitan versus regional Australia (p.11–12), of Australia’s standing in the world and of the impassioned debate on how modern-day societies might control gun violence. The book is rigorously researched and is well written. As a book reviewer, it is easy to commend Frame’s in-depth knowledge of such a tragic point in Australian history and the most obvious outcome of its aftermath. Critically, Frame asks if the National Firearms Agreement has achieved its intentions. As the title of the work suggests, this is an analysis of what was, in Frame’s view, done right and what was done wrong in a highly contested and very emotional space. Background is offered as well, with good summaries of the terrible massacres at Milperra (September 1984), Hoddle Street (August 1987), Queen Street (December 1987) and Strathfield (August 1991) (pp.82–88). The role of guns in perpetrating domestic violence is also mentioned. One of Frame’s more poignant lines is found in his acknowledgements when he thanks his ‘granddaughters Imogen and Lily, who remind me that women are the usual focus for the violent tendencies of men’ (p.195). To his credit, Frame reveals his own views upfront. He is, himself, a ‘licensed firearm owner’ but he does not ‘believe that keeping firearms is a right’. He notes his own belief that ‘Australian governments intrude too much on everyday life but accept[s] the need for highly restrictive firearm legislation.’ He also states that he ‘would probably own an AR-15 semi-automatic centre-rifle if the law allowed but fully endorse[s] the restrictions preventing [him] from having one’ (p.xvii). As a citizen in a world ravaged by gun violence it is difficult to not feel frustrated by Frame’s dispassionate delivery of what happened, when it happened and where. While this is a book about a very Australian experience and while some extrapolation to a broader, international, context can be made, it is difficult to directly compare the history offered by Frame to the quite different histories of gun violence in the United States. Yet, in early 2019 there were over one million registered guns in New South Wales alone, that “means there is now one registered firearm for every eight NSW citizens” (Gooley). A disturbing thought for many people. Perhaps I was, unfairly to Frame, looking for confirmation bias in this book and wanted an argument more laden with outrage than some half-way point between marching on the streets and the American response to massacres of ‘thoughts and prayers’. The most infuriating comments in Frame’s work are around his insistence to refer to guns as ‘firearms’. Utilisation of the word ‘weapons’ is, according to Frame, too provocative and is ‘intended by some to be pejorative rather than descriptive. Shooters own firearms; they do not become weapons unless they are used in the commission of a crime’. ‘A knife remains a knife’ Frame writes, ‘until it becomes a tool to harm another person’ (p.xix). Well, a broom remains a broom until it is wielded in a way that causes injury to another living being. Knives, brooms, cars, paperweights, an ugly vase; all of these items can be weaponised, but their fundamental purposes are practical and non-violent. In sharp contrast, firearms are designed to kill. Indeed, the sole purpose of a gun is to kill, be the intended victim an animal or another human being. Sure, some will argue ‘sport’ or ‘self-defence’ or ‘you need a gun out bush’. Yet guns are only ever weapons: from conception, to design, to manufacture, sale and use. These are tools of war. That said, the book will likely prove to be equally frustrating for those to identify as members of, or at least supporters of, various gun lobbies in Australia and around the world. This is Frame’s goal. It is, he argues, only from a ‘contested middle ground that progress can and will be made in dealing with issues that will not go away’(p.xvii). Frame includes a very useful glossary (pp.xxiv–xxix), if we are going to engage in these complex conversations we need to understand, clearly, the types of guns and rifles that dominate the statements made on gun ‘rights’ and gun ‘control’ and this is a first-rate quick guide. There is also a list of further reading, notes and an index. Gun Control neatly, and generally neutrally, is an informed and well-structured summary of a debate that, indeed, ‘will not go away’. If you want a solid, mostly impartial, history of gun control reform in Australia then Frame’s book is an excellent starting point. If you want to know that other people are really angry about senseless gun violence, then perhaps follow the Australian Gun Safety Alliance on Twitter. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2019 Visit the NewSouth Books website here.The last public hanging at Darlinghurst Gaol

The People's Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 25 September 1852, p2 via Trove

The People's Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 25 September 1852, p2 via Trove

The People's Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 9 October 1852 p9 via Trove

The People's Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 9 October 1852 p9 via Trove

'The morning of Tuesday broke dark and gloomy, with a drizzling rain; but this in no way diminished the number of spectators, which was of about the usual average—the proportion of females to the sterner sex being nearly three to one. We noticed one carriage in particular, tenanted by women of respectable exterior, and who, we believe, have hitherto ranked as such, drawn up immediately in front of the drop; its inmates displaying the most disgusting eagerness to source the best situation for witnessing the forthcoming tragedy.'Green’s final statement at his trial had proclaimed his innocence: 'May I be permitted to make one more remark. I am perfectly innocent of this charge, and if I am executed, I shall only add one more to the number of victims who have fallen on circumstantial evidence' Although he later confessed to accidentally killing Jones, his statement highlighted the moral issue behind the greater debate of the day: the fight to abolish the death penalty altogether, as both a public and private punishment. The decision of the New South Wales Legislative Council to perform judicial executions as private rather than public events was innovative but still controversial. There was a general consensus that public executions were uncivilised and were, as Gregory Woods has noted, 'associated with the hated convict era'. Yet there were those who believed that the ultimate sentence of the law was also the ultimate deterrent against crime and laws concerning the death penalty in the colonies required royal assent. Imperial authorities, who did not ban public executions in England until 1868, were not enthusiastic supporters of the new Australian policy, but finally Act to Regulate the Execution of Criminals 1855 (NSW) was signed and proclaimed on 10 January 1855. It is sometimes claimed that Green was the last person to be publicly hanged in New South Wales, but while Darlinghurst had two gallows, one private and one public, many other prisons across the state did not have these additional 'indoor' facilities, and the practice continued after 1852. Arguments for and against capital punishment continued, often vigorously, until it was eventually outlawed in all Australian states and territories in the late 20th century and legislation was passed by the federal government in 2010 prohibiting its reintroduction. References and further reading: Beck, Deborah, Hope in Hell: A History of Darlinghurst Gaol and the National Art School (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2005) 'The Buckley Creek Murder', Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 7 August 1852, pp1–3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/59775102; 'Law Intelligence', Empire, 3 August 1852, p2, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/60134731 'The Murder at the Turon', Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 8 May 1852, p4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101732377 , 'Police Intelligence', Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 8 May 1852, p4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101732377 Gregory D. Woods, A History of the Criminal Law in New South Wales: The Colonial Period, 1788–1900 (Annandale: Federation Press, 2002) Barry York, 'Capital Punishment in Australia', Unbound: National Library of Australia magazine, June 2017, https://www.nla.gov.au/unbound/capital-punishment-in-australia Dr Rachel Franks is the Coordinator, Education & Scholarship at the State Library of New South Wales and a Conjoint Fellow at the University of Newcastle. She holds a PhD in Australian crime fiction and her research on crime fiction, true crime, popular culture and information science has been presented at numerous conferences. An award-winning writer, her work can be found in a wide variety of books, journals and magazines as well as on social media. She's appearing for the Dictionary today in a voluntary capacity. Thank you Rachel! For more, listen to the podcast with Rachel & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Governor's Demesne

Plan of Governors Demesne Land, surveyed in the year 1816. By C Cartwright. From the collection of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales [a2869001 / ZM3 811.172/1816/1]

Plan of Governors Demesne Land, surveyed in the year 1816. By C Cartwright. From the collection of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales [a2869001 / ZM3 811.172/1816/1]

Listen to Minna and Tess on 2SER here

The Domain was established by Governor Macquarie along with the Botanical Gardens in 1816 when it encompassed a far larger area than we know today. Now only four small precincts, it used to cover the area from Woolloomooloo Bay to Circular Quay and south to Hyde Park. The edges were chipped away by the establishment of cultural institutions like the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the State Library of New South Wales, the Opera House, Government House and the Conservatorium of Music. Later road infrastructure carved out portions with the development of the Harbour Tunnel and ramps for the Cahill Expressway. During the day the Domain has always been characterised by picnics, cricket, public commemorations and weddings. But at night beneath the fig trees and on the lawns, Sydney’s lovers have found an alternate space. As early as 1832 Daniel Delaney was charged with 'making love to a ‘Shelah' in the Domain at the unseasonable hour of 11pm.’ For many of Sydney’s homeless it’s also been place of refuge. During the 1930s as people lost their jobs and failed to make rent, they turned to the Domain. A whole shanty town soon sprang up. At night there were campfires, as people gathered round billies of tea, gossiped and told stories. Perhaps most significantly the Domain represents a space where people can gather to protest, to rant and to rally. Speakers corner at the Domain, PIX, 18 March 1939, p20

Speakers corner at the Domain, PIX, 18 March 1939, p20

Demonstration in the Domain during the Great Strike, Sydney Mail 15 August 1917, p22

Demonstration in the Domain during the Great Strike, Sydney Mail 15 August 1917, p22

Fifty years of Kaldor Public Art Projects

View of Project 32: Jonathan Jones' barrangal dyara (skin and bones), Photo by Peter Greig, courtesy: Kaldor Public Art Projects

View of Project 32: Jonathan Jones' barrangal dyara (skin and bones), Photo by Peter Greig, courtesy: Kaldor Public Art Projects

Listen to the whole conversation with Mark and Sean on 2SER here

John Kaldor AO arrived in Sydney in the post-war years, his family on the move from Eastern Europe having survived war and invasion. Successful in the fabric industry, Kaldor first began to collect art and then in the late 1960s to commission public art. Kaldor first established a sponsorship for Australian artists to travel overseas, but from 1969 he reversed this, bringing in international artists to perform and make art here. The first big project, Project #1, was Christo and Jean Claude’s Wrapped Coast. The New York based Bulgarian and French artist couple were already internationally well known for their wrapped projects, wrapping store fronts and other objects as public art, but Wrapped Coast was by far their largest project to date. Over a period of two months, with the assistance of engineers, volunteers, art students and others, they wrapped a 2.4km section of Little Bay in Sydney with 92,900m2 of fabric and 56km of rope. The fabric and rope came from factories in Alexandria, then Sydney’s industrial heartland. Three years before the opening of the Opera House, and in a deeply conservative city, Wrapped Coast was a turning point for public art in Sydney. Many, without seeing it, thought it a terrible waste of money and pointless project. Hard to understand from a distance, those who were drawn in to see it, on the whole fell in love with the whimsy. Kaldor himself saw it as the start of a lifetime of support for public art. Puppy by Jeff Koons, Museum of Contemporary Art 1996 courtesy Jeannie Fletcher (JIGGS IMAGES) via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Puppy by Jeff Koons, Museum of Contemporary Art 1996 courtesy Jeannie Fletcher (JIGGS IMAGES) via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Sean here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Memory, Love and Gothic Horror

Headstones in Devonshire Street Cemetery c1901 by Ethel Foster, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON146/386)

Headstones in Devonshire Street Cemetery c1901 by Ethel Foster, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON146/386)

Detail of map showing different denominational burial grounds in the cemetery 1845, courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS1155, City of Sydney (Sheilds), 1845 (detail))

Detail of map showing different denominational burial grounds in the cemetery 1845, courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS1155, City of Sydney (Sheilds), 1845 (detail))

Headstone of Hugh McDonald, the first burial in Devonshire Street Cemetery in 1819, c1900, by Ethel Foster, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON 146/413a)