The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Flash coves, deep rogues and rascals

Painting by ST Gill, courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.obj-134655773)

Painting by ST Gill, courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.obj-134655773)

Sydney thrives on crime stories and today on 2SER Lisa thought she'd share a unique dossier held in the State Archives that gives a special insider’s view of law and order in Sydney in the 1840s.

You can listen to Nic and Lisa here: Listen now The dossier is called the Registry of Flash Men (State Records NRS 3406) and it was compiled in the 1840s by the superintendent (later commissioner) of police William Augustus Miles (1798-1851). The Registry is a vital record of the seedier side of Sydney as it shook off the shackles of transportation and a erected a more gentile facade over the Georgian town. In it we learn not only the names and behaviours of Sydney’s criminals, but also the language they (and Sydney's lower classes) used every day. Sydney’s crims spoke a ‘flash language’, or cant, a code amongst criminals. It was a marker of the convicts and criminal class, inherited from 18th century England. If you were a flash man, you were on the dodgier side of the law, using slang to communicate with other flash men to do your dodgy deals.Miles decided that it was important to know Sydney’s underworld and this was his official surveillance record. He kept tabs on known criminals and their associates, making connections and observing behaviour. This is detailed policing and investigative police work at a time much earlier than we might expect.

Cover of the Registry of Flash Men, courtesy State Records and Archives NSW (NRS 3406)

Cover of the Registry of Flash Men, courtesy State Records and Archives NSW (NRS 3406)

The notes seem to cover the period 1841 to 1846. The registry is formed at a time when there is growing public concern over criminal behaviour. Miles’ surveillance may have been covert, but it was not a secret; Miles publicly acknowledged it as part of his policing work in 1844:

“I have a great number of thieves under my eye in the town, who occasionally do a day’s work, and idle, gamble, and thieve, the rest of the time … I have taken great pains to inform myself how these men form themselves into gangs, and I keep a book relative to their movements, the parties who are their companions, and such other information as I may obtain respecting them …” (NSW Votes and Proceedings, 1844, Vol 2, Report from the Select Committee on the Insecurity of Life and Property, p 383)

Second page of the Registry of Flash Men, courtesy State Archives and Records NSW, (NRS 3406)

Second page of the Registry of Flash Men, courtesy State Archives and Records NSW, (NRS 3406)

Miles and his collaborators recorded aliases, appearance, ‘modus operandi’, known associates, places of residence, occupation, their character or temperament, sightings of them, details of previous convictions, incidents in which they were known or suspected of being involved, their circumstances, and information collected about them including quotations or comments from those who knew them and newspaper clippings.

The alias of a man named Hyams was, for example, “Hoppy my Heart” and the police superintendent notes that he had had his eye on this “rascal” for a while.

Various phrases are also recorded, such as “sell a man”, meaning betray a man, or “Oliver is in town”, meaning the moon is full. Others include:

“hocus pocus man” - meaning trickster or swindler,

“pigs”, “grunters” – meaning police

A “flash cove” – a thief or a fence.

An “exquisite around town” – a dandy or a fop

You could be arrested for being a rascal or a rogue, as you were assumed to be loitering and causing trouble. The information in the Registry paints a picture of life in Sydney, predominantly around the Rocks, where people would form gangs and pushes and life was much harsher than in the classes whose records are usually kept in our major collections. .To experience more of the Registry of Flash Men, take a look at this video on State Records’ website or go to their catalogue record here.

This is not the only record of Flash Language in Australia. “A New and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language” was written by James Hardy Vaux, a convict in Newcastle in 1812, specifically for magistrate in order that they could understand those appearing before them. It was published in London with Vaux's memoirs in 1819 and is also believed to be the very first dictionary compiled in Australia. You can read it online on the Internet Archive here.

A new and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language, written and compiled by James Hardy Vaux in 1812 and published in his Memoirs in 1819, via the Internet Archive

A new and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language, written and compiled by James Hardy Vaux in 1812 and published in his Memoirs in 1819, via the Internet Archive

Treating Sydney's sick

Detail showing the Sydney Infirmary from 'Bird's eye view of Sydney Harbour' by FC Terry, c 1856 courtesy National Library of Australia ( PIC Drawer 2407 #S1997)

Detail showing the Sydney Infirmary from 'Bird's eye view of Sydney Harbour' by FC Terry, c 1856 courtesy National Library of Australia ( PIC Drawer 2407 #S1997)

You can listen to their entertaining and informative conversation here:

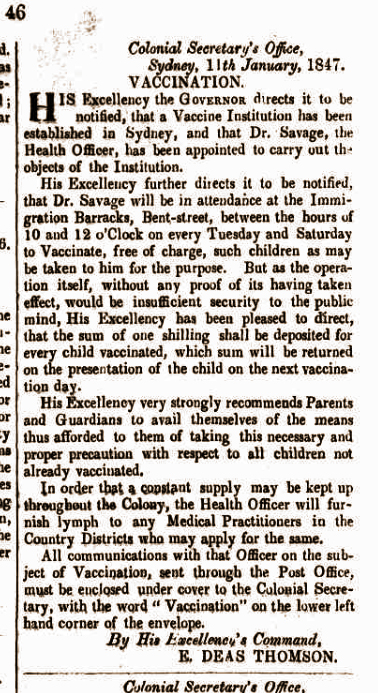

Until the late 1830s, hospitals in Sydney were provided by the government only for convicts, who they saw as a source of free labour, and government personnel like the military, employed to supervise the convicts and maintain the security of colony. This wasn't unreasonable in terms of what people thought about healthcare and hospitals at the time. If you were sick, you called in a doctor to visit you at home, or relied on family and friends for care, or you might make use of herbal and traditional remedies. If you were poor or indigent, you were dependent on the small number of charitable institutions who might be able to take you in. Hospitals were more like a convalescent home or hospice for the dying than we think of them today. Even into the 1870s, hospitals were still not places one would attend in anticipation of a full and rapid cure. If you were sick in the 19th century, the hospital was an option of last resort. New South Wales Government Gazette 12 January 1847, p46 via Trove

New South Wales Government Gazette 12 January 1847, p46 via Trove

A bed in the Infirmary was by no means a given, even by the 1860s. Sydney Punch, 4 September 1869, p128

A bed in the Infirmary was by no means a given, even by the 1860s. Sydney Punch, 4 September 1869, p128

Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver, Colonial Australian Fiction: Character Types, Social Formations and the Colonial Economy

Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver Colonial Australian Fiction: Character Types, Social Formations and the Colonial Economy

Sydney University Press, 153 pp, ISBN: 9781743324615, p/bk, RRP AUS$40.00

Colonial Australian Fiction: Character Types, Social Formations and the Colonial Economy (2017), from Sydney University Press, is the latest addition to the Sydney Studies in Australian Literature series. Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver — well regarded for a variety of scholarly achievements as well as for their excellent anthologies of colonial fictions (Adventure, Crime, Gothic and Romance) — have produced an elegant and very informative review of character types in colonial Australian fiction. Gelder and Weaver take readers beyond established stereotypes, facilitating opportunities to engage with “a remarkable range of character types, each of which enunciated a colonial predicament that was unique in so far as it projected the values, dispositions and desires that were specific to it” (p1). Of course, the idea of the character type is not new. Gelder and Weaver recognise this, quoting Mary Gluck who observed in 2005 that: “creating types and classifying them according to social categories represented a kind of modern ethnography, whose purpose was to achieve a comprehensive picture of contemporary humanity”, but then quickly assert that Colonial Australian Fiction highlights some of the tensions around this goal for a comprehensive picture. For types can “take control of a narrative, determining its priorities and ideological direction […but] types also change, they come and go, they interrupt, they mutate” (p4). The writing is, predictably, beautiful and nuanced. Innovative interpretations blend seamlessly with well-documented clichés. The “Squatter”, the “Bushranger” and the “Colonial Detective” will be known to many readers. The controversial squatters, their efforts at reinvention and projects of personal branding, are important to the understanding of Australian history and literature. These men sought large-scale influence and power while also asserting themselves as men of letters, as Gelder and Weaver quote (from Rolf Boldrewood’s 1873 novella The Fencing of Wanderowna: A Tale of Australian Squatting Life): “Surely, few people can enjoy reading so thoroughly as we squatters do” (p.30). The ubiquitous bushranger is traced from Michael Howe: The Last and Worst of the Bushrangers of Van Diemen’s Land (1818) by Thomas Wells through to A Bush Girl’s Romance (1894) by Hume Nisbet, thus, effectively covering the evolution of the bushranger from a reviled to a romanticised character. The detective, too-often overlooked by scholars, is also explored. John Lang’s A Forger’s Wife (1855) is presented as the first detective novel in Australia (pre-dating Ellen Davitt’s Force and Fraud: A Tale of the Bush, the first Australian murder mystery, by a decade). The character of the detective is critical within the corpus of colonial fiction as this investigative type unravels puzzles within the plot while simultaneously offering clues into the Australian character. What we think about law, order, punishment and forgiveness can be seen through the characters of detectives and those who surround them. The “Bush Type” and the “Metropolitan Type”, more regularly accessed through art and poetry (indeed, William Strutt’s fantastic and very familiar 1887 painting Bushrangers graces the cover of the book), are also surveyed. Gelder’s and Weaver’s argument for reading these characters as complex and diverse, as well as how such characters have changed, is an important rebuttal to superficial assertions of the bush/metropolitan man as an either/or designation. The “Australian Girl” is another example of how complicated, and occasionally contradictory, colonial characters are. She is distinguishable by the 1860s but her lineage from the “Currency Lass” is outlined (p117) before this type is taken through to colonial maturity and the beginning a new century. In this section, Gelder and Weaver pay significant attention to Sybylla Melvyn of Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career (1901) and the struggle to identify with something greater than herself but to also be independent, to be an individual. “I am proud” she writes, “that I am an Australian, a daughter of the Southern Cross, a child of the mighty bush. […] Would that I were more worthy to be one of you” (p137). She is, explains Gelder and Weaver, an exemplification of the predicament of the national type, “normative and ‘deviant’ at the same time” (p137). This liminal space occupied by Melvyn allows us to see the difficulties faced by writers in creating (and reflecting on) the great types of colonial Australian fiction: the reinventors, the law breakers, the law enforcers, those who made their way on rugged landscapes and those who occupied built environments, the men and women who defined colonial fiction and set the foundations for Australian literature of the twentieth century. Colonial Australian Fiction is an essential volume for anyone curious about Australian literary heritage, for these types are more than just characters on a page: they are our enemies and our friends, our neighbours and our political leaders, the relatives we would prefer not to acknowledge and the people we have fallen in love with. They are why many of us read fiction. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, January 2018 For a preview of the book or to purchase online, visit Sydney University Press here.Animals on the Dictionary of Sydney

Felix the Cat toy which was mascot of the Gun Plot Room on the HMAS Brisbane, courtesy Australian War Memorial (REL32980.022)

Felix the Cat toy which was mascot of the Gun Plot Room on the HMAS Brisbane, courtesy Australian War Memorial (REL32980.022)

Inspired by yesterday’s wayward wallaby crossing the Sydney Harbour Bridge, today Nicole thought she’d take a look at some other animals mentioned on the Dictionary of Sydney.

One very famous animal on the Dictionary has been described as the world’s first animated celebrity. Well before Mickey Mouse came along, Felix the Cat was delighting audiences of the silent film era, first appearing on screens in 1919, and the man who claimed responsibility for Felix's creation was a former Sydneysider. Cartoonist and producer Patrick O’Sullivan was born in Paddington in 1885, the son of a Darlinghurst cab driver. By 1905 he was submitting cartoons, caricatures and illustrations to The Worker, the trade union affiliated newspaper. O'Sullivan left Sydney in 1909 and ended up in New York in 1914. There he became known as Pat Sullivan and from his studios in 1919 came the now world famous cat. Felix appeared in over 100 films and by the mid-1920s, the Felix comic strip was published by 60 newspapers worldwide. While there is some contention about who actually created the Felix character, with Otto Mesmer, another animator in Sullivan's studio also credited by many, Sullivan's studio produced the films and he held the copyright for the name and at least 200 different Felix toys until his death in 1933. You can watch some early Felix the Cat cartoons online courtesy of the Internet Archive here. Another famous animal in Sydney’s past could be found at Tamarama, in Australia’s first large scale open-air amusement park Wonderland City. The park featured an artificial lake, Australia’s first open-air ice skating rink, a merry-go-round, Haunted House, labyrinth, 1,000-seat music hall and a Japanese tearoom. Among the more novel attractions was the ‘Airem Scarem’ dirigible, a floating airship suspended on a cable which extended over the sea. Another one of its indubitable attractions was Alice the elephant. An Asian female elephant who had arrived in Australia with the English company Bostock & Wombwell's travelling menagerie in 1905, Alice was purchased by Wonderland City's proprietor William Anderson in 1906 when she and the menagerie's other livestock were put up for sale when the menagerie's director returned to Britain. At Wonderland City she was dubbed ‘the children’s friend’ and was the subject of a weight-guessing competition and carried a couple in an 'Oriental marriage celebration' witnessed by 30,000 people. Princess Alice at Wirth's Bros Circus in Sydney, 1938, from PIX 7 May 1938), p47 via Trove

Princess Alice at Wirth's Bros Circus in Sydney, 1938, from PIX 7 May 1938), p47 via Trove

Sydney summer

Click here to read the latest Dictionary of Sydney newsletter

Click here to read the latest Dictionary of Sydney newsletter

Sydney Punch, August 29, 1868, p 114

Sydney Punch, August 29, 1868, p 114

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing operational funding and needs your help to continue.

Make a tax-deductible donation to the Dictionary of Sydney today!

Zeny Edwards, A Life of Purpose: a biography of John Sulman

Emeritus Professor David Carment launched this book at the State Library of NSW on 15 December 2017 and he has generously given us his permission to publish the text of his speech.

Emeritus Professor David Carment launched this book at the State Library of NSW on 15 December 2017 and he has generously given us his permission to publish the text of his speech.

Zeny Edwards, A Life of Purpose: a biography of John Sulman (2017) 392 pp, ISBN-13: 9780648171928, RRP: $59.95

I felt honoured when Zeny asked me to launch her wonderful new book and was pleased to accept the invitation. I am here wearing two hats. First, I am John Sulman’s eldest great grandchild. Second, I am also a professional historian whose interests include Australia’s historic built environment and family history. I never met my great grandfather. He died in 1934 and I was not born until 1949. His widow Annie died a day after I was born. My mother Diana, however, was his eldest granddaughter, shared his architectural, artistic and town planning interests, and often discussed him with me. She was justifiably proud of his achievements. From time to time we visited buildings that he designed. She also closely followed the art and architecture awards that honoured him. During family holidays in Canberra she spoke of her grandfather’s contributions to the national capital’s design and planning. The Sydney house where I now live, which previously belonged to my parents, has some of his framed architectural drawings on its walls. His large architect’s desk, a reproduction of John Longstaff’s Archibald prize winning portrait of him, and many books that he owned are in my study as is the clock presented to him in 1919 by his students in New South Wales’s first town planning course at the University of Sydney. Until they were given to the State Library of New South Wales almost ten years ago, I looked after a large collection of his papers, photographs and plans. Growing up in Sydney during the 1950s and the 1960s I knew all his surviving children: Florence, always known as Florrie, Arthur, Joan, my grandfather Tom, and John, usually called Jack. None is still living but I keep in contact with his only surviving grandchild Meryn, who resides in the United States. I particularly enjoyed the family gatherings Florrie hosted at the attractive arts and crafts style house in Collaroy that her father designed for her, sadly now demolished. During these gatherings Florrie and her siblings sometimes reminisced about him. While researching my doctoral thesis at the Australian National University in the early 1970s I was intrigued to discover that John Sulman was for a while quite closely associated with my thesis subject, the federal politician Littleton Groom who between 1918 and 1921 was the minister responsible for Canberra’s development. I found both then and later that Sulman was widely recognised as a major figure. In Darwin, where I lived for 25 years, I learned from my PhD student Eve Gibson, a historian of town planning, that his garden suburbs ideas influenced significant aspects of the city’s development. Even leaving aside my obvious family bias, it was clear from the work of other historians, perhaps most notably Robert Freestone’s influential publications on the development and theory of modern planning in Australia, that he deserved a full biography and it was disappointing that there was none. At one stage the prominent architectural historian Max Freeland was collecting materials for such a biography but for various reasons it never came to fruition. Another well-known architectural historian, the late Trevor Howells, also began work on a Sulman biography but, like Freeland, did not complete the task. I wondered when I first learned from my mother that Zeny Edwards was interested in writing about Sulman whether or not she would persist. Once I got to know her, however, I had no doubt at all that she would. She demonstrated a determined, enthusiastic and wide-ranging interest in Sulman and his work. She had, as well, all the necessary research and writing skills, and a proven record of commitment to the documentation of Australia’s cultural heritage. As she proceeded with the biography my mother and I were impressed with her progress. Zeny’s doctoral thesis, on which her book is based, was completed not long after my mother’s death but other family members and I greatly enjoyed reading it. Although I thought I knew quite a lot about my great grandfather, there was much in the thesis that was new to me. Until Zeny used them, researchers had not examined many of the primary sources on which A Life of Purpose is based. Some were privately held and not well organised. They included records at my parents’ home in Mosman and my cousin Lea’s property about an hour’s drive from Tamworth. Zeny visited buildings that Sulman designed. Her research also encompassed an enormous variety of other sources, such as organisational records and articles in periodicals. The book devotes considerable attention to Sulman’s family background, early life, education, the origins of his ideas, the numerous buildings for which he was responsible in Britain and Australia, his role in professional bodies, his extensive public activities, his town planning career, his patronage of the arts, his two wives and their children, and his private life. The contributions he made to public debates, such as that regarding a tunnel or bridge connecting Sydney Harbour’s north and south shores, are explored and interrogated. Although Zeny is generally a sympathetic biographer, she analyses, as she should, Sulman’s cunning self-promotion, nervous breakdowns, and conflicts with professional colleagues. Also mentioned is how his knighthood only came after he lobbied the federal government to secure it. I found the discussion of Sulman as a husband and parent especially illuminating. In spite of being a strict disciplinarian and often living in Sydney while his younger children were growing up in the Blue Mountains, he was a far more attentive and supportive father than I had previously believed. Zeny refers to three great family tragedies he experienced: the deaths while they were all still young of his first wife Sarah, his daughter Edith and his son Geoffrey. She also writes about how in his last days Sulman was more worried about his children’s well being than his own. Zeny convincingly shows how as a public intellectual Sulman helped shape his adopted country’s national identity. ‘Sir John Sulman’s presence’, she concludes, ‘is still very much felt … the Sulman name has become a part of the vocabulary of Australian architecture, town planning and the arts’. A Life of Purpose is logically organised and clearly written. Handsomely produced, it has numerous well-chosen images. While its scholarship is impeccable, it is also highly readable. I am delighted that this significant contribution to Australian biographical and historical literature is now published and congratulate Zeny on her achievement. I encourage you all to purchase copies. Emeritus Professor David Carment December 2017 A Life of Purpose will be available in 2018 at all good booksellers and the publisher's website here. You can read Zeny Edwards' entries on the Dictionary of Sydney here.Underworld: Mugshots from the Roaring Twenties - exhibition review

Underworld: Mugshots from the Roaring Twenties, which has just opened at the Museum of Sydney, is an exploration of crime in a decade that heralded the brave new world that emerged from the devastation of World War I.

Curated by the indefatigable Nerida Campbell this exhibition profiles some of the many men and women from Sydney’s seedy underworld who were at large across the city in the early twentieth century.

The exhibition focuses on the “Specials”: a collection of photographs taken by police photographers in a way that would not prejudice a person, looking at an image, against a suspect. These are not your typical mugshots. In these photographs, suspects hold handbags, papers, cigarettes and conversations. This approach allows at least a part of someone’s personality to be captured; thus, many of the images are like commissioned studio portraits, potentially destined to reside on a dressing table or mantelpiece. If the tell-tale marks of name, date and fingerprint classification were removed, many would be surprised to learn that these photographs were taken by police and that the subjects had been accused of many different types of crimes.

The exhibition designers have done wonderful work. The photographs — reproduced from glass plate negatives — have been presented in a way that provides a sense of the original object. The fragility of that medium offers a fabulous juxtaposition to the hard men and women captured in the negatives and has generated an elegant line of images, with glass serving as a subtle motif throughout the space.

The room for temporary exhibitions at the Museum of Sydney is small and has proven to be a challenging venue for previous installations. This effort, with over 130 photographs, is well laid out and the modest gallery even manages to accommodate a small, Art Deco-influenced, cinema. There is, too, an area set aside to don the attire of a felon of the 1920s and stand near a replica of a bentwood chair (used to gauge a suspect’s height) and take your own “mugshot”. It was crowded on opening night, but it was still easy to move around and to see everything that was on display. The text throughout is necessarily brief but is engaging and informative.

Usually the felons in the collections of Sydney Living Museums are sequestered at the Justice and Police Museum, on the edge of Circular Quay; a metonym for being on the edge of society. The decision to relocate these photographs from these surrounds to the Museum of Sydney might be seen as controversial by some who enjoy the criminal context provided by the old Water Police Station and Courts, but presenting this exhibition at the Museum allows the viewer to see these stories of criminals in new ways: to see these men and women as more like “us” and a little bit less like “them”. This line, that divides those who obey laws and those who are willing to break them, is further complicated by the quality of the images. Reconciling a beautiful photograph with the litany of crimes committed, from petty theft to sexual assault, can be challenging. Indeed, it can be difficult to turn away from some of the faces that stare through time, meeting the gaze of the photographer in the 1920s and, today, casually returning the stare of anyone interested in gangland Sydney of nearly a century ago.

It is easy to classify crime as cheap entertainment, but crime is complicated. Attempts to create a black and white world of ‘bad’ and ‘good’ does not explain crime today, it never has. Stories of crime — the criminals, the victims, the police — are all layered. There are narratives of bad people doing bad things; there are also, in many cases, backstories of abuse, poverty and single mistakes that have escalated into a career of criminal activity. Sometimes we will never know why. The social milieu of some did not facilitate the exposure of the truth. For others, the historical record is incomplete as details have been lost, or at least obscured. Underworld captures some of these complexities, offering a suite of dramatic as well as sophisticated stories.

There is a companion book and a website: both are worthy of exploration.

Review by Dr Rachel Franks, December 2017

Underworld runs until 12 August 2018 at the Museum of Sydney. Further details about the exhibition, associated talks and events are available on the Sydney Living Museums website: https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/underworld

Underworld: Mugshots from the Roaring Twenties, which has just opened at the Museum of Sydney, is an exploration of crime in a decade that heralded the brave new world that emerged from the devastation of World War I.

Curated by the indefatigable Nerida Campbell this exhibition profiles some of the many men and women from Sydney’s seedy underworld who were at large across the city in the early twentieth century.

The exhibition focuses on the “Specials”: a collection of photographs taken by police photographers in a way that would not prejudice a person, looking at an image, against a suspect. These are not your typical mugshots. In these photographs, suspects hold handbags, papers, cigarettes and conversations. This approach allows at least a part of someone’s personality to be captured; thus, many of the images are like commissioned studio portraits, potentially destined to reside on a dressing table or mantelpiece. If the tell-tale marks of name, date and fingerprint classification were removed, many would be surprised to learn that these photographs were taken by police and that the subjects had been accused of many different types of crimes.

The exhibition designers have done wonderful work. The photographs — reproduced from glass plate negatives — have been presented in a way that provides a sense of the original object. The fragility of that medium offers a fabulous juxtaposition to the hard men and women captured in the negatives and has generated an elegant line of images, with glass serving as a subtle motif throughout the space.

The room for temporary exhibitions at the Museum of Sydney is small and has proven to be a challenging venue for previous installations. This effort, with over 130 photographs, is well laid out and the modest gallery even manages to accommodate a small, Art Deco-influenced, cinema. There is, too, an area set aside to don the attire of a felon of the 1920s and stand near a replica of a bentwood chair (used to gauge a suspect’s height) and take your own “mugshot”. It was crowded on opening night, but it was still easy to move around and to see everything that was on display. The text throughout is necessarily brief but is engaging and informative.

Usually the felons in the collections of Sydney Living Museums are sequestered at the Justice and Police Museum, on the edge of Circular Quay; a metonym for being on the edge of society. The decision to relocate these photographs from these surrounds to the Museum of Sydney might be seen as controversial by some who enjoy the criminal context provided by the old Water Police Station and Courts, but presenting this exhibition at the Museum allows the viewer to see these stories of criminals in new ways: to see these men and women as more like “us” and a little bit less like “them”. This line, that divides those who obey laws and those who are willing to break them, is further complicated by the quality of the images. Reconciling a beautiful photograph with the litany of crimes committed, from petty theft to sexual assault, can be challenging. Indeed, it can be difficult to turn away from some of the faces that stare through time, meeting the gaze of the photographer in the 1920s and, today, casually returning the stare of anyone interested in gangland Sydney of nearly a century ago.

It is easy to classify crime as cheap entertainment, but crime is complicated. Attempts to create a black and white world of ‘bad’ and ‘good’ does not explain crime today, it never has. Stories of crime — the criminals, the victims, the police — are all layered. There are narratives of bad people doing bad things; there are also, in many cases, backstories of abuse, poverty and single mistakes that have escalated into a career of criminal activity. Sometimes we will never know why. The social milieu of some did not facilitate the exposure of the truth. For others, the historical record is incomplete as details have been lost, or at least obscured. Underworld captures some of these complexities, offering a suite of dramatic as well as sophisticated stories.

There is a companion book and a website: both are worthy of exploration.

Review by Dr Rachel Franks, December 2017

Underworld runs until 12 August 2018 at the Museum of Sydney. Further details about the exhibition, associated talks and events are available on the Sydney Living Museums website: https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/underworld

‘The past lives on’:Paul Keating’s Redfern speech

Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating giving speech at the launch of the United Nations' International Year of the World's Indigenous People, Redfern Park 10 December 1992 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (SRC24730)

Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating giving speech at the launch of the United Nations' International Year of the World's Indigenous People, Redfern Park 10 December 1992 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (SRC24730)

‘The starting point might be to recognise that the problem starts with us, the non-Aboriginal Australians. It begins, I think, with an act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases and the alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice and our failure to imagine that these things could be done to us. With some noble exceptions we failed to make the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds. We failed to ask – how would I feel if this were done to me? As a consequence, we failed to see that what we were doing degraded us all.’Listening to the recording of the speech, you can hear the crowd cheering these words as Keating acknowledges the dispossession, violence and discrimination endured by Aboriginal people. These cheers continued as he spoke of the important contributions Indigenous Australians had made, and also for the need to reinterpret the past.

Launch of International Year of World's Indigenous People at Redfern Park, 10 December 1992 Courtesy National Archives of Australia (A6135, K24/12/92/9)

Launch of International Year of World's Indigenous People at Redfern Park, 10 December 1992 Courtesy National Archives of Australia (A6135, K24/12/92/9)

- FactCheck Q&A: are Indigenous Australians the most incarcerated people on Earth?, Thalia Anthony, The Conversation, 6 June 2017

- Australian Bureau of Statistics: 4517.0 - Prisoners in Australia, 2016

Vanessa Berry, Mirror Sydney

Vanessa Berry, Mirror Sydney

Vanessa Berry, Mirror Sydney

Giramondo Publishing, 2017, 304 pp, ISBN: 9781925336252, p/bk, RRP AUS$39.95

The very title of Mirror Sydney says a great deal about Vanessa Berry’s take on her hometown. It’s inspired by an aged photograph album found in an op shop, featuring an image of Sydney on the front cover which is reversed – indeed mirrored – on the back. And, just like this optical inversion, Vanessa’s take on Australia’s largest city is so much more than mere reflection. In Mirror Sydney we accompany Vanessa on her gentle expeditions and memory journeys through the psychic hinterland of the metropolis. Ever curious, ever alert, and always generous, she finds fascinating flashes of forgotten futures. Tempted by suburbs she has never visited, the author is ceaselessly beguiled by glimpses of kitsch, relics of urban lore, and snippets of personal remembrance. So are we. In the same warm, easy prose of her blog, Vanessa draws us into her explorations through times, spaces and moods that once were but are no more. Indeed, she even provides maps: hand-drawn sketches crafted in loving detail and annotated with anecdotes. History seeps into her stories, but it’s an elusive past – the sort that most of us struggle to retain when waking from a poignant dream. Vanessa’s art lies in caressing those traces back from the edge of memory and thatching them into her tales. “I can only imagine the Magic Kingdom in its prime”, she writes, “in images like those of faded and blurry old photographs” (p85). There’s a real warmth here, and it’s not simply civic pride. Place is certainly important: her city and its expansive suburbs nestle in the bosom of the book. But what I love most about Mirror Sydney is its method, a pleasant perambulating psychogeography that could re-enchant anywhere, giving the book an appeal well beyond Sydney. The prose is evocative without being ebullient, sensitive to the meanings we imbue in the quotidian filigree of our surroundings. Eschewing Robin Boyd, who half a century ago decried The Great Australian Ugliness, this book recalls the spirit of Robert Venturi’s seminal postmodern architecture manifesto, Learning from Las Vegas. For Venturi and for Vanessa, delight dwells in the details of urban mundanity. “The recent past still lingers around the present like a shadow, lurking in the shapes of buildings and shop signs, echoing in rumours” (p63). Buy this book and listen to those echoes. Reviewed by Dr Peter Hobbins, December 2017 Mirror Sydney is available at all good bookstores and via the publisher’s website here. You can also explore Vanessa Berry's blog Mirror Sydney here.Everything old is new again

Completed escalators at the York Street entrance of Wynyard Station, 17 August 1931, courtesy State Archives & Records NSW (12685_a007_a00704_8735000024r)

Completed escalators at the York Street entrance of Wynyard Station, 17 August 1931, courtesy State Archives & Records NSW (12685_a007_a00704_8735000024r)

Boarding a tram at the intersection of King and George Streets c1905 by Frederick Danvers Power, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a422003 / ON 225, 160

Boarding a tram at the intersection of King and George Streets c1905 by Frederick Danvers Power, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (a422003 / ON 225, 160

Sydney's first trams were drawn by horses when they were introduced in 1861, but this service only lasted until 1866.

A steam tram was introduced in 1879 - as is so often the case, the impetus for the new infrastructure was a big public event. Enormous crowds were expected for the International Exhibition in the Botanic Gardens in 1879 and the tram service was proposed to bring people from the railway terminus, close to the current location of Redfern station, into the city almost to the gates of the Garden Palace.

Despite some initial scepticism from the public, the line was an immediate success and the original plans to demolish it once the Exhibition had closed were abandoned. In 1880 the government decided to build on its success and committed to building more tramways in the city and further into the suburbs.

Sydney's extensive tram network was at its peak in 1922, but the Depression, followed by WWII, saw the geographical spread of the network halt. By the 1950s a number of factors including the decentralisation of industry and the rise in ownership of private automobiles meant that government priorities had changed and in the early 1960s we pulled up the tracks.

Removal of tram tracks George Street 1960 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 48/1190)

Removal of tram tracks George Street 1960 Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 48/1190)

But now they're back! Trams won't be running on the new tracks until 2019 so it will be a while yet until we know what its like to catch a tram down George Street.

In the meantime, you can walk on some of the tracks, visit the Tramway Museum in Loftus, go down to the revamped Tramsheds at the Harold Park development and eat in a restored tram, or admire one of the many tram waiting shed that are dotted around the city and currently serve as old bus shelters, like the stand at the intersection of Park and Elizabeth Streets.

You can also check out everything the Dictionary has on trams here, including a very informative article here about the history of Sydney's trams written by Dictionary stalwart Garry Wotherspoon.

We had trams running down George Street previously of course - watch this extraordinary film footage from the National Film and Sound Archive made by someone sitting on the top of a tram filming as the tram went up George Street towards the QVB, and imagine what it will be like. Pedestrians, bicycles, carts all weaving their way around the trams. We've done it before and we'll do it again!

We had trams running down George Street previously of course - watch this extraordinary film footage from the National Film and Sound Archive made by someone sitting on the top of a tram filming as the tram went up George Street towards the QVB, and imagine what it will be like. Pedestrians, bicycles, carts all weaving their way around the trams. We've done it before and we'll do it again!