The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Shirley Beiger

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Shirley Beiger

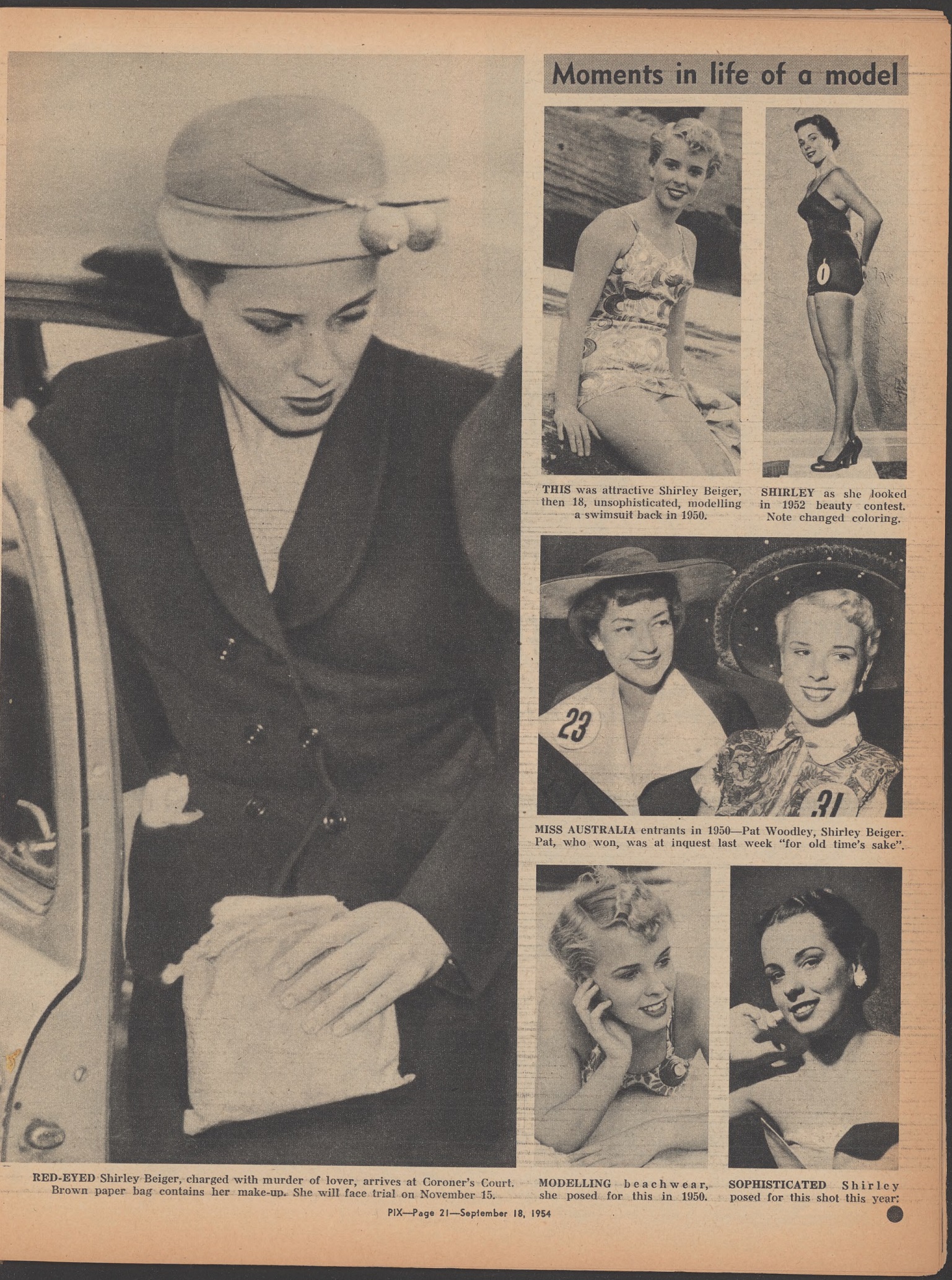

Shirley Beiger was a model who shot and killed her lover, Arthur Griffith, outside the nightclub Chequers in 1954. She was acquitted of the crime and her trial gained significant national media attention at the time.

'blonde, attractive Shirley Beiger'

[media]Shirley Patricia Beiger was born on 20 March 1932. Her parents, Edith and Maurice Beiger, also had two older children, Shirley’s elder brothers Jack and William (Bill). Initially Beiger attended local public schools, and then went to the Sydney Church of England Girls Grammar School in Darlinghurst. Her parents divorced in 1945 and Beiger lived for several years after this with her father. When she was about 17 she went to live with her mother above the sandwich shop that Edith ran in Redfern. When asked in court in 1954, she described her childhood as a happy one, not mentioning her father’s physical abuse of her mother and her mother’s gaol terms on sly grog charges.[1]

Beiger left school at 14 and by 17 had worked at a variety of jobs including as an office clerk, a hairdresser, and as a salesgirl. She was working as a florist’s assistant in an Orchid Bar at David Jones when she was offered her first modelling job and decided this was the ‘kind of life’ she wanted, and her mother sent her to modelling school. In 1950 she was a semi-finalist in the Miss Australia beauty pageant. Between 1951 and 1954 ‘blonde, attractive Shirley Beiger’ appeared a number of times in PIX magazine, including on the cover.

[media]Around 1953, Beiger moved by herself into a flat at 3 Kellett Street, Kings Cross and met Arthur Griffith through a mutual friend and neighbour, Don Lee who was a waiter at Chequers nightclub. Twenty-three year old Griffith, who worked as a clerk for his father, bookmaker AC Griffith, officially lived with his parents at 30 Primrose Avenue, Rosebery[2] but regularly stayed at Kellett Street and had his own key to the flat. He was described in Truth as ‘handsome, clean cut, impeccable, a keen sports player, but a regular night-club habitue’.[3]

'I knew something dreadful must have happened'

[media]On the night of 9 August, Beiger and Griffith had been in the Kellett Street flat, when Griffith said he had to go out for a dental appointment. Beiger was suspicious that Griffith might be lying and was seeing another woman. She went in search of him and found that he had gone to Sammy Lee’s nightclub in York Street. She then caught a cab to see her mother in Coogee, and she and Edith drove back to the city in her mother’s car to confront him. Finding he’d left Sammy Lee’s, they decided to keep looking for him.

[media]As they drove around Griffith’s preferred venues, they saw his ute parked near to Chequers nightclub on King Street. Griffiths had indeed gone out that night with another woman and had earlier in the evening accompanied Chequers showgirl Gill Bowen-Daniels to see a film at the Embassy cinema.[4]At about 11pm Beiger and her mother saw Griffith ‘come down King Street with a girl on his arm and go into Chequers’. Beiger followed them into the club where they argued, and she demanded that Griffith return the keys to her flat.

Her mother drove Beiger home to Kellett Street, where she said she would collect Griffith’s clothes and golf clubs, so she could ‘throw them on the dance floor’. She also went to Don Lee’s room on the same floor and took his .22 Browning repeater rifle, loaded it, and took it along with the golf clubs to the car ‘thinking I would tell him if he didn’t come home with me I would shoot myself’.[5] Back in the city, they parked near the corner of King and Pitt Streets, and Beiger asked her mother to go into Chequers and get Griffiths from the club. When he emerged, he came over to the car where Beiger was sitting in the back seat, wearing her grey overcoat and elbow length white gloves:

‘I was holding something with my right hand. I didn’t know at the time what it was – it must have been the gun.’

[media]Beiger said she did not remember Griffith approaching the car. The first thing she knew was that he was at the window. Beiger said Griffith had remarked he would be home later, and she added:

‘He just gave me a push and told me not to be a silly kid, like he did when we had had words.’

She said she did not hear the gun actually go off.

‘I didn’t realise what had happened…but I knew something dreadful must have happened.’[6]

The police were called and arrived soon afterwards. Griffith died at the scene. He had been shot in the face and the bullet had entered his brain. Beiger was arrested and taken to Long Bay jail.

[media]Beiger applied for bail several times, apparently so that she could visit Griffith’s grave and see his parents. She advised that she had heard from Griffith’s family, ‘whose attitude was one of kindness and sympathy’.[7] Her applications were all denied.

At the inquest on 8 September, a friend of Griffith’s came forward to say that Griffith had told him about coming home late one night and finding Beiger asleep in bed holding a rifle.[8]

'There is no crime of passion in our jurisprudence'

[media]Beiger’s trial opened on Monday 22 November 1954. Huge crowds waited outside the court, ‘day long queue[s] of sensation-seekers, armed with cut lunches and refreshments’, some with babies in their arms. ‘Those who missed out calmly opened their thermos flasks and settled down for the three hour wait until the luncheon adjournment when the public galleries would be cleared and they would get priority seating for the second session’.[9]

Beiger’s counsel was the high profile barrister Jack Shand, QC, supported by Phil Roach and Lionel Murphy. The defence they presented to the charge of her having shot Griffith at point blank range was that she had merely intended to frighten Griffith, whom she had seen with another girl, but he had given her a push and a rifle she was holding went off.

The trial was briefly interrupted by a mentally unwell faith healer from Newcastle who left the public seats and came to the Bar table, declaring he would be representing Beiger.[10]

When Beiger was called to the witness box: ‘She remained in the box for nearly an hour, answering questions in a soft, almost inaudible voice – a speech stifled by sobs and great emotional strain’[11]

In summing up on 23 November, Justice McClemens instructed the all male jury that ‘There is no such thing as a crime of passion in our jurisprudence’, warning them that, because Beiger was a ‘not unattractive young woman’, they should not be swayed by motives of compassion’.

His Honor told the jury that they could bring in three verdicts — guilty of murder, guilty of manslaughter or not guilty of both. He said that if the jury decided Beiger had acted with intent to kill Griffith, or had acted with reckless indifference to his safety, or with intent to commit grievous bodily harm, it was their duty to convict of murder.

If the jury found that the rifle was unreasonably pointed at the deceased and went off accidentally without any intention to kill or cause grievous bodily harm they had to bring in a verdict of manslaughter.

Every jury, where the accused was charged with murder had the right to bring in a verdict of manslaughter, he said.[12]

[media]The jury retired at 5.25pm and returned its verdict at 7.40pm, ‘not guilty of murder or manslaughter’:

‘150 people members of the public in court cheered and clapped wildly for two minutes’. When the noise stopped. Mr Justice McClemens said: ‘I wish to point out to the people guilty of this display that their conduct was gross and in the extreme… A court of justice is a solemn place.’[13]

Another crowd of hundreds had gathered outside the Darlinghurst court and also burst into cheers soon after 7.40pm when a woman ran from the court shouting, ‘She’s not guilty!’. Beiger’s mother Edith who was sitting in a car nearby, almost collapsed.[14]

Griffith’s father was present for the verdict and when asked his opinion, replied:

“It makes no difference. There’s nothing we can say. We accept the verdict. Had she been given life imprisonment it would not have brought our boy back. The whole thing has been pretty hard on us.”[15]

'Models are Nice People'

Apart from an early report after which the Sun was accused of contempt for publishing a photo of Griffith with the headline ‘Murder Victim’, the Sydney press showed almost unreserved sympathy for ‘the beautiful, blonde model and cover girl’ throughout, with the story being reported around the world.The rights to her personal story were purchased by Associated Newspapers for £1250 (approximately $50,000) in the days following her arrest, and an exclusive interview with the Sun's Oliver Hogue followed her acquittal.[16]

The tabloid press was particularly colourful:

‘Shirley Beiger says Models are Nice People’ cried the Sun[17] while Truth declared that:

’Arthur Barry Griffith died and that was the greatest tragedy of all. Shirley Patricia Beiger lost the man she loved, and that was another tragedy. And when a girl finally found that all the glitter was not gold… that too was a tragedy.’[18]

Her former neighbours in Redfern were interviewed in the Sun-Herald:

‘We all liked Shirley. She was the sort of girl who would stop and help an old lady with her bundles any time’ while ‘A close friend of Arthur Griffith’ said ‘Arthur would have wanted it this way – he would have wanted Shirley to be acquitted.’

The outfits and hairstyles she wore to face court were eagerly relayed across the country ‘Beiger appeared in court wearing a fashionable slate-grey gabardine tent coat buttoned right to the neck. Her corn-coloured hair was cut in the latest ‘poodle’ style’[19] and ‘Miss Beiger dressed in the black suit she wore yesterday, a wide-brimmed hat, and yellow gloves.’[20]

Even the ‘wardress’ at Long Bay, Gloria Hughes, provided the ‘intimate story of jail life’ of ‘Shirley Beiger, prisoner’ for publication on the front page of the Sun:

‘I watched as Shirley showed kindness and generosity and an ability to share what she had, both material and spiritual’.[21]

The 1975 musical, Chicago, in which characters Velma Kelly and Roxie Hart both murder their respective husband and lover and are subsequently acquitted, was based upon real life stories by journalist Maurine Watkins about Chicago in the 1920s when all male juries were notorious for acquitting female murderers who were supported by the press and ‘sob sisters’ (women journalists):[22]

'Who could forget Cora Orthwein crying out to the police after killing her cheating sweetheart back in 1921? "I shot him," she wailed. "I loved him and I killed him. It was all I could do'[23]

A note that Beiger had written in jail just hours after the murder similarly suggests the story of a faithful woman who apparently loved her man 'too much':

'I was livid to think that he had lied to me – I had put the heater on and warmed all his clothes before he put them on so he wouldn’t be cold, I wanted to believe he was going to the dentist because I didn’t want to know he was lying to me… I was just the girl who washed his clothes, cooked his food and ran after him doing all odd jobs even cleaned his shoes so he would be nice for other girls. I understood when he said he was sorry about not being able to take me to nightclubs as he was short of money so I was content to stay home and let him go out with the boys and I waited for him to come home when he had nowhere else to go – I guess I just loved him too much.'[24]

Australian journalist Phillip Knightly said in 1997 that it was apparent from early on that ‘Shirley Beiger was going to walk free. It was my introduction to the way skilled lawyers can manipulate juries.’[25]

‘Women said that Griffith was a two-timing bastard who deserved everything he got. Men said that if women were allowed to shoot every two-timing bastard in Sydney, there would not be enough cemeteries to hold them.’[26]

'Model vanishes'

After she was acquitted, Beiger’s supporters went through an elaborate ruse to avoid the press, smuggling her out of the back of the court and having other women decoys driven around the city[27] while Beiger stayed with her mother at the home of her brother Bill and his wife at Bondi.[28]

Her version of ‘My Story’, was serialised in the Sun over the following week, while the Truth ran exclusive photos on the front page and the ‘real’ story behind Shirley Beiger.[29]

She received telegrams, flowers and chocolates from the public, before leaving Sydney ‘for a holiday in the country’.[30]

In December, Beiger's solicitor Roach issued two writs on her behalf claiming a total of £10,000 (approximately $350,000) in damages against John Fairfax and Sons Pty Ltd and Associated Newspapers Ltd, and the Bathurst National Advocate Ltd [31] after the publication of a brief comment article in the Sun-Herald that appeared to imply she was a murderer.[32] The case was settled out of court. [33]

In early January, it was rumoured that Beiger and her mother were planning to travel on the Orontes to London. Press swarmed over the ship at every port from from Sydney to Fremantle hoping to gain an interview with her until a ship’s officer finally advised that the booking had been cancelled just before sailing.[34]

By March 1955, Beiger was living and working quietly in Melbourne[35]. She never gave another interview or reappeared in the press.

Further Reading

Jenny Hocking, Lionel Murphy: A Political Biography, Cambridge University Press, Oakleigh, 2000

Tony Reeves, Getting Away With Murder - The First Trilogy of the Series: True Stories of Australians who got away with murder, Reeves Lourensz Group, Brisbane, 2009

Notes

[1] Slugged for being silent, Truth, 23 April 1944, p23 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168761390; Sydney Morning Herald, 22 May 1946, p6; This was seemingly her father’s second divorce, the first in 1928 IN DIVORCE, 26 October, 1928, The Sydney Morning Herald, p8

[2] Shirley Beiger is acquitted: cheers in court, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 November 1954, p1

[3] The Shirley Beiger Story, Truth, 28 November 1954, p53

[4] Tony Reeves, Getting Away With Murder - The First Trilogy of the Series: True Stories of Australians who got away with murder, Brisbane: Reeves Lourensz Group, Brisbane, 2009, p65

[5] Shirley Beiger’s sobs hold up shooting inquest, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 September 1954, p4; ‘Sad, sordid’ Judge says, Truth, 29 August 1954, p1

[6] Beiger says she wasn't bitter, Sun, 23 November 1954, p2

[7] Wants to see grave: Dr's report on model, Sun, 23 August 1954, p2

[8] Strong emotions at close of shooting inquest, Courier Mail, 8 September 1954, p3

[9] Babies taken to trial of model, Melbourne Herald, 1 December 1954, p4

[10] Butted into Beiger Trial, Sun, 23 November 1954, p1

[11] Judge warns Beiger jury on 'unwritten law', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 November 1954, p6

[12] Judge warns Beiger jury on 'unwritten law', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 November 1954, p6

[13] Sydney model not guilty, Cairns Post, 24 November 1954, p1

[14] Model, 22, acquitted, Courier Mail, 24 November 1954, p1

[15] Sydney Model Freed on Both Counts, Canberra Times, 24 November 1954, p1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2909306

[16] Vancouver Sun, 24 November 1943, p14; Daily Oklahoma, 24 November 1954, p38; 8 November 1954 Memo on purchase of rights to Shirley Beiger story. Fairfax Media Limited Business Archive, File 71: Memos Between Sun Editor and Mr R A Henderson Managing Director, 1953-1963, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW MLMSS 9894/Box 1527; 8 March 1955, Correspondence from Minter, Simpson & Co to Mr AH McLachlan, General Manager, John Fairfax & Sons, Fairfax Media Business Archives, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, MLMSS 9894/Box 303, File 076: Beiger, 1954-1955; £100 was also paid to her solicitor Phil Roach for assistance securing the rights.

[17] Shirley Beiger says: Models are nice people, Sun, 29 November 1954, p5

[18] All that glittered was not gold: the change in the life of Shirley Beiger, Truth, 28 November 1954, p50

[19] ‘Driven to it’ Claim over murder charge, Courier Mail, 11 August 1954, p3

[20] Daughter-model listens with head bowed, Adelaide News, 7 September 1954, p3

[21] Shirley Beiger, prisoner, Sun, 24 November 1954, p1

[22] Douglas Perry, The Girls of Murder City: fame, lust, and the beautiful killers that inspired Chicago, Penguin Group /Viking Press 2010, New York, Chapter 1

[23] Douglas Perry, The Girls of Murder City: fame, lust, and the beautiful killers that inspired Chicago, Penguin Group /Viking Press, New York, 2010, Chapter 1

[24] Model tells of long search on night of shooting, Daily Telegraph, August 25, 1954, p7; NSW Supreme Court, File no.37/1954; AO No.3/1996 Beiger as quoted in Jenny Hocking, Lionel Murphy: A Political Biography, Cambridge University Press, Oakleigh, 2000. p36

[25] Phillip Knightley, A hacks progress, Jonathan Cape, London, 1997 p50

[26] Phillip Knightley, A hacks progress, Jonathan Cape, London, 1997 p50

[27] Model Vanishes, The Sun, 24 November 1954, p1

[28] Shirley Beiger's Writs, Sun, 1 December 1954, p11

[29] Oliver Hogue, Shirley Beiger says This is My Story, Sun, 26 November 1954, p5; Sun, 29 Nov - 1 December 1954; Exclusive! No longer a gay girl, Truth, 28 November 1954, p1,50

[30] Flowers, gifts pour in for Shirley Beiger, The Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate, 30 November 1954, p5

[31] Shirley Beiger sues newspaper, Townsville Daily Bulletin, 9 December 1954, p9

[32] Candid Comment by Onlooker: New Version, Sun-Herald, 28 November 1954, p26

[33] 31 March 1955, Memo from the General Manager to Mr Henderson, Managing Director, Fairfax Media Business Archives, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ML MSS 9894/Box 303, File 076: Beiger, 1954-1955

[34] A quest but no quarry, Mirror (Perth), 8 January 1955, p3

[35] 31 March 1955, Memo from the General Manager to Mr Henderson, Managing Director, Fairfax Media Business Archives, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ML MSS 9894/Box 303, File 076: Beiger, 1954-1955