The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

SEARCH THE DICTIONARY

COPYRIGHT

The Dictionary of Sydney brings together the intellectual property of a large number of contributors in an innovative way. All of the content you will find here has been provided to us by others and the Dictionary is not the copyright holder of much of the material appearing within the project. We have received permission to use, for our purposes, everything you find here. If you wish to use any of this content for your purposes (above and beyond normal personal use or uses permitted by copyright law such as ‘fair dealing’) you will need to make a direct request to the owner.

Text

All articles (also known as entries) in the Dictionary of Sydney are newly commissioned texts from the listed authors and have been licensed to the Dictionary for its use, adaptation and integration into our project (present and future).

The copyright in each article lies with its listed author(s) who retains the right to license it commercially, publish elsewhere, adapt or otherwise exploit their rights as the copyright holder. The Dictionary of Sydney has an Input Agreement for individual contributors providing written entries and for institutions providing, mostly, multimedia resources of various kinds.

Authors

The Input Agreement for individual authors includes three key points:

- Authors keep copyright in their work.

- Authors are responsible for ensuring that they do not submit material for which copyright clearance has not been obtained.

- The Dictionary reserves the right to reformat material to take advantage of the possibilities of digital presentation. We will not, of course, do anything to alter the substantive meaning of an author’s words and authors will always be acknowledged.

Submitted work is edited and returned to authors for final acceptance. We also undertake document, picture, film and audio research. When the essay is reproduced online it will be presented with a range of images, maps, audio clips, reproduction of documents, reading lists, downloadable pdfs and so on. New possibilities may arise as the technology matures.

In many cases, authors also agree to license their work under Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike (version Au-2.5) (commonly referred to as CC-BY-SA). The Creative Commons licence describes the circumstances under which third parties may use articles without having to ask permission or pay fees. This is a voluntary licence and it encourages the wider dissemination and use of the information. Articles which are so licensed are clearly indicated by the CC-BY-SA logo next to the title. You can see the full details of the CC-BY-SA licence here.

In summary, this licence means that third parties are specifically allowed to copy, distribute and adapt the article provided that they attribute the original source, and that adaptations, such as translations, abridged versions or new articles based on the original, are made equally free for others to further adapt and re-use under the same CC-BY-SA licence.

If you would like to re-use article(s) in ways not permitted under this licence you need to contact the author(s) to gain specific permission. Text such as captions, subheadings, descriptions and blog posts are written in-house.

Multimedia

The Dictionary of Sydney has partnered with a wide range of public institutions, commercial companies and individuals to find and license multimedia items (images, video, audio) to associate with our articles. The Dictionary has sought and received specific permission to use each one of these items in the project.

If you wish to re-use this content you need to undertake your own copyright assessment and/or contact the listed provider (look for the Contributor and Creator information with the content record on the site). We have made best efforts to obtain permissions and show the correct attribution, citation and metadata for all material in the Dictionary but if you believe we have made a mistake or omission, please contact us.

In some circumstances we have used multimedia items which have been published elsewhere with one of the several Creative Commons licences available. We have indicated this fact within the metadata of the item.

If you would like to know more about the copyright status of such an item please check at the location where the item was first published. Attribution texts (metadata) are supplied by the provider of the multimedia items and are either their copyright or not copyrightable.

Technology

For information on copyright as it relates to the technology of the Dictionary (software, website design, model) please click here.

SEARCH THE DICTIONARY

Welcome to the Dictionary of Sydney

The site was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney is a website about the history of Sydney – its urban myths, characters, political players, writers, dreamers, intellectuals, sports people, criminals – anyone and everything that contributes to Sydney’s story.

From the Hawkesbury River in the north, Port Hacking in the south, the Blue Mountains in the west and the Pacific coast in the east, our aim is to gather as much information as possible about all aspects of Sydney’s history including its natural features, built forms, structures, significant events, artefacts, organisations, places and people.

Our purpose

The Dictionary publishes historical and cultural information about Sydney for the broadest possible audience, whether residents or visitors, students or researchers, or people just interested in Sydney.

The Dictionary is updated regularly to include new content.

Our contributors

At the heart of the Dictionary is the dedicated scholarship of more than 400 volunteer authors who give their work to the project. They range from eminent professors and professional historians to local experts and enthusiasts of all kinds. A full list of authors published to date can be found here.

The Dictionary has agreements with a range of institutions and individuals that allow us to use material from their collections in the Dictionary. Without them, it would be a far less interesting and exciting project. A full list of these institutions and collections can be found here.

Our organisation

Conceived in 2004, the Dictionary of Sydney grew out of an Australian Research Council project supported by the University of Sydney in partnership with University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), State Library of New South Wales and State Records, with the City of Sydney as industry partner.

Launched in November 2009, the Dictionary of Sydney website continues to grow.

In 2014 we launched our free mobile app for smart phones and tablets which makes available several free self-guided walking tours around parts of Sydney.

After providing support since 2006, in December 2016 the City of Sydney ceased to fund the Dictionary on an annual base. In 2017, the Dictionary’s content was moved onto a new platform at the State Library of New South Wales to ensure its preservation.

In September 2018, the Dictionary of Sydney Inc was wound up and management of the Dictionary passed to the State Library of New South Wales. As the Dictionary has no ongoing financial support, publication of new content will cease when funding runs out.

Partnerships

Since 2017 the Dictionary has been part of the State Library of New South Wales.

The Dictionary has community partnerships with many of Sydney’s other leading cultural institutions and universities as well, such as State Archives and Records NSW, History Council of NSW, Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, University of Sydney and the University of Technology, Sydney.

Sponsors of Dictionary projects have included the Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities; Transport Heritage NSW; Liverpool Council; Maritime Museums of Australia; NSW Department of Environment and Heritage; Oral History NSW; Royal Australian Historical Society; Randwick City Council and the Sydney Mechanics School of the Arts.

The Dictionary continues to enter into collaborative projects that can enrich our understanding and appreciation of Sydney in areas such as:

- History and heritage

- Reconciliation

- Community expression and identity

- Academia and education

- Local, state and federal government

- Digital technology and multimedia

- Arts and creative industries

- Civic pride and public interest

SEARCH THE DICTIONARY

Featured blogs

Read all blogsAbout Dictionary of Sydney

This site was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney is a website about the history of Sydney – its urban myths, characters, political players, writers, dreamers, intellectuals, sports people, criminals – anyone and everything that contributes to Sydney’s story.

Listen on 2SER

Listen to the archive of interviews and stories about the Dictionary of Sydney.

So long Sydney

Miss Australia 1957 Helen Wood farewelled at Mascot, March 1958, State Library of NSW (APA 05090)

Miss Australia 1957 Helen Wood farewelled at Mascot, March 1958, State Library of NSW (APA 05090)

The Dictionary of Sydney is an incredible project. It all started back in 2005 when a group of historians and industry partners secured a 5-year Australian Research Council grant to present Sydney's history in a digital format to explore the possibilities of linking different historical entities lie people, places and things through time. It was at the forefront of the digital humanities and of crowdsourcing projects. Listen to Lisa and Wilamina on 2SER here Those visionaries were working at the University of Sydney, the City of Sydney, the University of Technology Sydney, State Records NSW, and the State Library of NSW. Together they established the Dictionary of Sydney. (Step back in time and have a look at the project site in 2006 on the Internet Archive here and through the first annual report on Pandora here!) The initial website went live in 2009 (check out our first front page on the Internet Archive here) and a passionate group of volunteers, with minimal paid staff, have been researching, writing and adding content ever since. Nearly 300 authors have shared their research in about 1050 entries. An additional 133 cultural collections, institutions and private collectors have also contributed material to the Dictionary of Sydney - everyone from the National Library of Australia, to the British Museum, all the state libraries around Australia, archives, art galleries, local studies collections, as well as individual photographers, artists and collectors. Together these contributions make up more than 5,500 multimedia objects - photographs, illustrations, artworks, posters, maps, film and moving footage, audio and oral histories. And we can't forget all those amazing facts and lists that have been researched, collated and linked in the entity records, creating relationships between entries, entities and media. There's a reason we call these the building blocks of the Dictionary! People soon started to take notice, and wanted to learn more about Sydney's history. Eight years ago, the new breakfast presenter at 2SER - Tim Higgins - approached me to do a regular segment on the show. That was back in June 2013 and we've been doing it ever since! Every week volunteers have been sharing with you something about Sydney's history and we've been putting up the blog posts here. 2SER has been an amazing supporter of the Dictionary of Sydney. It's been so much fun. But now it's time to say goodbye. The Dictionary of Sydney was transferred to a new platform at the State Library a couple of years ago in preparation for gradually winding down as funding came to an end, and over the next few months or so, work will begin on archiving the site for posterity. So don't panic! You'll still be able to access all your favourite articles, search the website and answer all those tricky questions, friendly disputes and pub quizzes. Thanks to the Library, the Dictionary will remain available as a reliable source of historical information about Sydney.

PIX, 14 July 1951, p30, State Library of NSW (TN 18)

PIX, 14 July 1951, p30, State Library of NSW (TN 18)

In our final radio segment on 2SER, some of the recent regular radio contributors wanted to share some of their favourite picks from the Dictionary of Sydney. What are yours?

Lisa

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is the 20201 Dr AM Hertzberg AO Fellow at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide.You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio These four entries for me demonstrate the breadth of the Dictionary's content: The Cocky Bennett Story by Catie Gilchrist, avian stalwart of the Sea Breeze Hotel at Tom Ugly's Point: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/the_cocky_bennett_story Francis & Frederick Ellard, by Graeme Skinner, musicians and music publishers kick-starting Sydney's popular music scene. Anyone care to dance the Quadrille?: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/ellard_frederick Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen by Grace Karskens. Always was, always will be: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/barangaroo_and_the_eora_fisherwomen Kings Cross by Mark Dunn - as Mark says, 'Kings Cross exists in Sydney's imagination as much as it does in any physical form': https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/kings_cross The fun fact that will win you that pub quiz: Louie the Fly was a cartoon character in an advertisement created for Mortein in 1957 by Bryce Courtenay: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/artefact/louie_the_fly Favourite images: Bodgie Styles for Spring 1951 from PIX - what can I say? It's out there: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/5157 Bondi Lady, Bondi 1975 by Rennie Ellis - wish I was there: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/1208 Stained glass by Beverley Sherry - ok, it's an article but it's the images that make it. They absolutely pop: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/stained_glass

Rachel

Dr Rachel Franks is the Coordinator of Scholarship at the State Library of NSW and a Conjoint Fellow at the University of Newcastle. She holds a PhD in Australian crime fiction and her research on crime fiction, true crime, popular culture and information science has been presented at numerous conferences. An award-winning writer, her work can be found in a wide variety of books, journals and magazines as well as on social media. Her biography of NSW hangman Robert Rice Howard 'Nosey Bob' will be published in 2022.

Cemetery and the active gallows, detail from 'Plan de la ville de Sydney' 1802, Dixson Map Collection, State Library of NSW (Z/Ce 82/2 detail)

Cemetery and the active gallows, detail from 'Plan de la ville de Sydney' 1802, Dixson Map Collection, State Library of NSW (Z/Ce 82/2 detail)

These are some of the articles I return to again and again. A history of death and dying in colonial Sydney (a terrific amount of detail) by Lisa Murray: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/death_and_dying_in_nineteenth_century_sydney An overview of the suburb of Darlinghurst (much more than a gaol) by Mark Dunn: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/darlinghurst and Australia's first bank robbery by Neil Radford https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/robbing_the_bank_australias_first_bank_robbery (so close to getting away with it). My favourite blog posts include one that looks at women in cricket by Minna: Throw Like a Girl https://home.dictionaryofsydney.org/throw-like-a-girl/ and one that looks at wining and dining by Nicole Cama: Sydney's Wining and Dining Evolution https://home.dictionaryofsydney.org/sydneys-wining-and-dining-evolution/ One of the best images, I think, on the Dictionary is a detail of the cemetery and the active gallows from the 'Plan de la ville de Sydney' 1802 https://dictionaryofsydney.org/image/100423 A fabulous piece of audio is attached to a history of coffee by Garry Wotherspoon, Listen to this excerpt of an interview by Poppy Stockell with Luigi Coluzzi, boxer-turned-barista, talking about his life in Sydney: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/1748 Did you know? Founders of The Bulletin - John Haynes and JF Archibald - were unable to pay court costs after being taken for libel and so did a stint in Darlinghurst Gaol in 1882: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/person/haynes_john

Cover of book 'The Shark Arm Case' by Vince Kelly, published by Horwitz Publications 1963, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 343.1/30A1)

Cover of book 'The Shark Arm Case' by Vince Kelly, published by Horwitz Publications 1963, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 343.1/30A1)

Minna

Minna Muhlen-Schulte is a professional historian and Senior Heritage Consultant at GML Heritage. She was the recipient of the Berry Family Fellowship at the State Library of Victoria and has worked on a range of history projects for community organisations, local and state government including the Third Quarantine Cemetery, Woodford Academy and Middle and Georges Head . In 2014, Minna developed a program on the life and work of Clarice Beckett for ABC Radio National’s Hindsight Program and in 2017 produced Crossing Enemy Lines for ABC Radio National’s Earshot Program. You can hear her most recent production, Carving Up the Country, on ABC Radio National's The History Listen here. Some of my favourite entries on the Dictionary include: Woolloomooloo by Shirley Fitzgerald for some frank and fearless commentary on socio-economics/gentrification: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/woolloomooloo The myth of Sydney's foundational orgy by Grace Karskens https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/the_myth_of_sydneys_foundational_orgy Fun fact 'Getting off at Redfern' is the colloquial expression for a particular form of contraception - depending on which side of the Bridge you live on of course: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/artefact/getting_off_at_redfern Images Skeleton of the Dugong found at Shea's Creek 1896: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/4614 'Thanks Jack' Builders Labourers Federation Protest 1973 by Rennie Ellis: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/2802 Cover of book 'The Shark Arm Case' by Vince Kelly, published by Horwitz Publications 1963: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/59327 18 footers racing Sydney Harbour 1921 by Harold Cazneaux, by kind permission of the Cazneaux family: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/2535 Blog posts Newcastle Hotel with Mark: https://home.dictionaryofsydney.org/the-newcastle-hotel/ Drama of Llamas from Rachel: https://home.dictionaryofsydney.org/a-drama-of-llamas/ The squire of Enmore House: Joshua Frey Josephson by Lisa: https://home.dictionaryofsydney.org/the-squire-of-enmore-house-joshua-frey-josephson/

'But if we demolish the pub instead won't we be accused of acting against Australian tradition?' 1959 by George Molnar, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an25047016)

'But if we demolish the pub instead won't we be accused of acting against Australian tradition?' 1959 by George Molnar, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an25047016)

Mark

Dr Mark Dunn is the author of ‘The Convict Valley: the bloody struggle on Australia’s early frontier’ (2020), the former Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association and former Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here and follow him on Twitter @markdhistory here The Irish (albeit in the very very distant past) in me nominates the entry on the history of St Patrick's Day celebrations in Sydney that was supported by Consul General of Ireland: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/celebrating_st_patricks_day_in_nineteenth_century_sydney The next project I'm working on means I'll choose Mark Howard's Sydney Whaling Fleet article: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/sydneys_whaling_fleet And the "Hey I wrote that and it was fun to do" in me nominates Joseph Fowles: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/fowles_joseph And for images I cannot go past George Molnar's cartoon 'But if we demolish the pub instead won't we be accused of acting against Australian tradition?': https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/2398 Published in 1959 when the historic St Malo at Hunters Hill was demolished, it goes to the heart of heritage, except now they do demolish the pub as well. All of the fabulous Dictionary presenters over the last eight years have appeared in a voluntary capacity, and we're so grateful to them for their generosity in sharing their time and expertise to bring us all of these Sydney stories. We're also grateful for the chance to work with 2SER and the amazing breakfast show hosts and producers who've made this collaboration such a joy every week! Listen to the Dictionary's final segment on 2SER with Lisa & Wilamina here, and check out all the other blogs and audio we've posted together with 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning over the last eight years here!

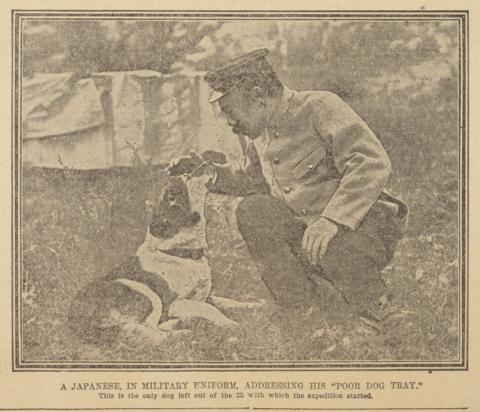

Japanese Antarctic expedition camp at Parsley Bay 1911

A member of the Japanese expedition in the camp at Parsley Bay soon after arrival with the expedition's only surviving dog, Daily Telegraph, 13 May 1911, p15

A member of the Japanese expedition in the camp at Parsley Bay soon after arrival with the expedition's only surviving dog, Daily Telegraph, 13 May 1911, p15

The extraordinary occurrence of Japanese Antarctic explorers camped at Parsley Bay may not be well known but it is a touching story of cross cultural and scientific exchange of ideas on Sydney’s foreshore. Listen to Minna and Wilamina on 2SER here In 1910 the 27-member crew of the Kainan Maru ( roughly translated as ‘Opener up of the South’) left Tokyo under Lieutenant Nobu Shirase bound for the Antarctic. They were in competition with Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and British Robert Scott. However, they left later in the year than planned and weren’t very well prepared. By the time they pulled into Wellington, New Zealand, 27 of their sled dogs had died. In March they reached the Antarctic circle but the grim winter setting in forced them to turn back before getting on land. They headed back north and pulled into Parsley Bay before their ship underwent repairs at Double Bay and then Balmain. Because of the restrictions of the Australian Immigration Restriction Act (the basis of the White Australia Policy) most of the crew initially had to stay crew aboard but an exemption under the Act permitted scientists from the East to come ashore if they stayed under 6 months. They were offered space at Vaucluse by the Wentworth estate and quickly erected a demountable wooden hut and canvas tents up to house the scientists and officers, who were eventually joined by the crew. Some Sydneysiders were suspicious of their presence. Against the backdrop of the Sino Japanese War and Russo Japanese War, the Australian media had often run headlines such as ‘The Japanese Menace’ and ‘The Japanese Scare.’ Even though no evidence or suggestion of spying could be found, the Royal Australian Artillery quietly installed guards at the South Head forts. However public perception was turned around by the attention and support from geologist Professor Edgeworth David, himself a former Antarctic explorer to the Antarctic. He shared his knowledge with them became great friends with Lieutenant Shirase.

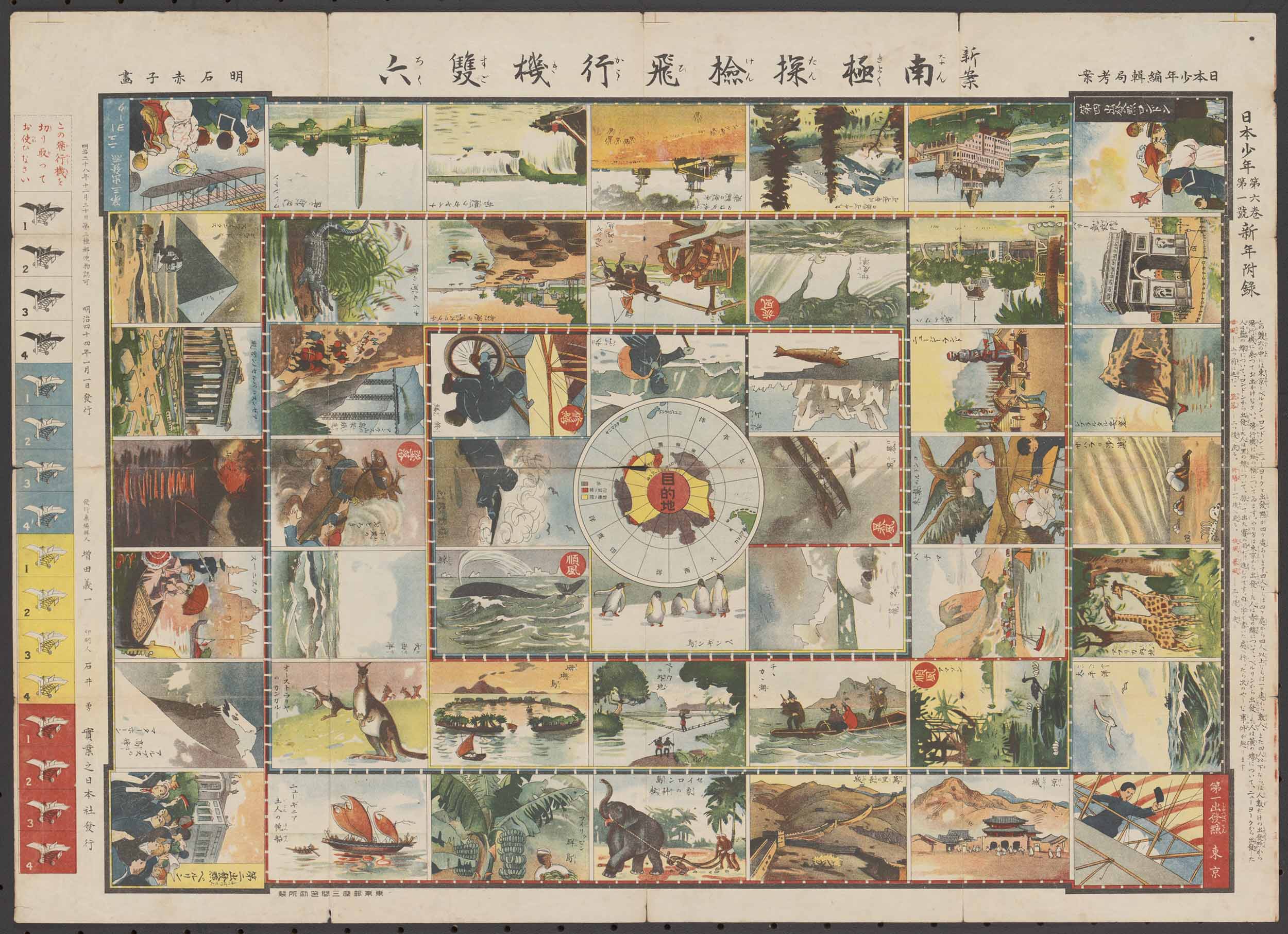

Japanese Antarctic Aeroplane Expedition board game (Nankyoku tanken hikōki sugoroku ) 1911

Japanese Antarctic Aeroplane Expedition board game (Nankyoku tanken hikōki sugoroku ) 1911Game of Antarctic polar exploration that was published as supplement to Japanese children's magazine, 'Nihon shōnen' in 1911. Each of the four players represents a different power: Japan, Germany, France, or the United States. The players start in Tokyo, Berlin, Paris and New York (located at the four corners of the board), and race each other to the South Pole in the centre, with penalties for hazards en route. National Library of Australia (JAP Pic 83)

The camp soon became a fixture with Sydney children wandering in and given souvenirs like Japanese newspapers or sweets. The children also taught the visitors popular songs in English, like 'Yip-I-addy-I-ay', while the explorers demonstrated ju-jitsu display, a traditional temple play, singing and Japanese food. Even the Vaucluse Council was won over with the camp, conceding: If all the citizens of Vaucluse behaved themselves as well, and obeyed sanitary instructions as carefully as these men had done, the suburb would be a very beautiful one. On Sunday 19 November 1911, the Kainan Maru set sail again through the heads, bound again for Antarctica, once more reaching their furthest point south of 80° 5 in Antarctica on 28 January 1912. Returning via Wellington and a side trip to Sydney, they received to a hero’s welcome in Tokyo. Today there is little evidence of the Japanese camp in Parsley Bay except for a memorial plaque. A 17th century Japanese samurai sword given to Professor David by Lieutenant Shirase as a gesture of thanks and friendship is now at the Australian Museum, where it is a valued emblem of the relationship between the two countries. For more pictures and information, read Kim Hanna's entry on the Japanese Antarctic Expedition at Parsley Bay on the Dictionary of Sydney here: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/japanese_antarctic_expedition_camp_at_parsley_bay_1911 Minna Muhlen-Schulte is a professional historian and Senior Heritage Consultant at GML Heritage. She was the recipient of the Berry Family Fellowship at the State Library of Victoria and has worked on a range of history projects for community organisations, local and state government including the Third Quarantine Cemetery, Woodford Academy and Middle and Georges Head . In 2014, Minna developed a program on the life and work of Clarice Beckett for ABC Radio National’s Hindsight Program and in 2017 produced Crossing Enemy Lines for ABC Radio National’s Earshot Program. You can hear her most recent production, Carving Up the Country, on ABC Radio National's The History Listen here. She’s appearing for the Dictionary today in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Minna! For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Minna & Wilamina here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

A matter of life and death – the coroner in New South Wales

The role of the coroner in New South Wales has existed for 234 years – longer, in fact, than the state itself. On 2 April 1787, Governor Arthur Phillip was granted the powers ‘to constitute and appoint justices of the peace, coroners, constables and other necessary officers’ for the new colony, just weeks before he embarked on the long journey to Australia aboard the First Fleet. Back then, the role of the coroner reflected British ideas about ‘sudden and unnatural deaths’ and how to investigate them. Listen to Darrienne and Wilamina on 2SER here What is a coroner? The modern definition of a coroner comes from the Coroner’s Act 2009. The Act empowers the coroner to assess and explain two things: the manner of a person’s death, and the cause of death. The manner of death classifies how an injury or disease process caused a person’s death and includes five categories: natural death, homicide, suicide, accident and undetermined. The cause of death is the specific injury or disease process that leads to a person’s death. The modern coroner also investigates the origins of fires and explosions that destroy or damage property within New South Wales, including big cases like the Luna Park Fire in the 1970s and the 1994 Eastern Seaboard Bushfires. Of course, it is not the coroner’s role to explain all deaths in the state; only those where the manner and cause of death has not been determined. Approximately 6000 deaths are reported to the office of the NSW state coroner each year, including 3000 occurring within the Sydney metropolitan area.

Commission to John Dight to act as a coroner in the Colony of New South Wales, 4 June 1828, Mitchell Library, State LIbrary of NSW (Safe 1/4b)

Commission to John Dight to act as a coroner in the Colony of New South Wales, 4 June 1828, Mitchell Library, State LIbrary of NSW (Safe 1/4b)

What was life like for early coroners? From their surroundings to their legal support, colonial coroners had a very different experience to the modern NSW state coroner. For over a hundred years, for example, the role of the coroner was supported by a mandatory jury of twelve. Naturally, finding twelve willing men from a population of a few thousand was often a difficult task for a coroner in colonial Sydney; this would have been practically impossible in rural areas. Early coroners weren’t working with a dedicated building or morgue, either, at least until the middle of the nineteenth century. They travelled widely and often, having to traverse large swathes of country to attend cases, with inquests held in local pubs or the rooms of the deceased. The position wasn’t as unpleasant as one might think – the colony was relatively small, meaning minimal contact with corpses, and the pay attractive. This unique role – and its pay cheque – attracted various interesting characters during the early days of the colony. Governor Macquarie selected John Lewin as the coroner for the town of Sydney and the surrounding County of Cumberland in 1810. Though he served in the role until his death in 1819, Lewin’s real passion was art – he was the colony’s first professional artist and published Australia’s first illustrated book, Birds of New Holland. Lewin’s successor, George Panton, wasn’t convinced of the position’s charms, resigning after just two months as coroner in November 1819 to take the role of Postmaster for New South Wales. Another colonial coroner, George Milner Slade, was especially colourful. Originally a paymaster for the 6th Battalion 60th Foot Regiment of the British Army, Slade was dismissed over a scandal in Jamaica involving misappropriated funds. Though inexperienced in most professions, the charming Slade managed to land on his feet, securing the office of coroner in 1821 to the tune of ninety pounds a year. Following a successful seven years as coroner, Slade opened several stores, went bankrupt, and still managed to secure further high-paying appointments in the New South Wales and Queensland colonies. Morgues and courts The first formalised morgue in New South Wales was established in 1853, under experienced coroner John Ryan Brenan. Sick of the constant movement and uncertainty of his role, Brenan floated the idea of constructing a dedicated morgue near Cadman’s Cottage in Circular Quay.

Photographers and journalists outside the Coroner's Court, The Rocks c1930 by Sam Hood, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXE 789 (v.14), f30)

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, morgues were more commonly (and crudely) known as dead houses. The Dead House at Circular Quay, which came to be known as the North Sydney Morgue, was designed by Colonial Architect William Weaver, and built by Thomas Coghlan. Both Weaver and Coghlan’s careers plummeted during the construction of the morgue, with Weaver resigning over financial issues and Coghlan prosecuted by the Crown for falsifying work hours. Despite this kerfuffle over work hours, the resultant Dead House was little more than ‘a room with a table on it’, as later noted by a disgruntled coroner, with space for only two bodies. If other cadavers were present, jury members would have to step over them; the only place for more than two bodies was on the floor. The stench of decomposing corpses was often unbearable for the twelve jury members, who preferred to attend inquests held in more appealing public houses such as the Observer Tavern nearby. The returns from interested patrons and thirsty jury members was an inviting prospect for local publicans. The North Sydney Morgue remained in operation until the resumption of The Rocks at the turn of the twentieth century, when it was demolished alongside many other colonial buildings to rid the city of the threat of plague. The building was so dilapidated by 1901 that the Evening News referred to it as ‘the old tin shed at the Circular Quay’. Meanwhile, the role of the coroner was changing. In 1861, an Act was passed ‘to empower Coroners to hold Inquests concerning fires’, as well as the power to grant bail to people charged with manslaughter as part of an inquest. The 1901 Coroners Act gave local coroners two intriguing extra powers; the legal power of a justice of the peace and the right to hold an inquest on a Sunday. This disturbance of the Sabbath was likely an unpopular choice with jurors. A new combined Dead House and Coroner’s Court in the Rocks was completed in 1908 to the tune of £4235. Constructed from dark brick with a sandstone trim, the building was considered state of the art, with a glass-walled room available for viewing bodies and a dedicated laboratory. The court also provided separate waiting rooms for male and female witnesses. The advent of science As knowledge about the human body rapidly increased, so too did coronial practices. By the early 1900s, post-mortem examinations became a key part of how inquests were investigated. The chief medical officer of New South Wales at the time was Dr Arthur A Palmer. His vast experience earned him the nickname ‘The Post-Mortem King’. Science was moving too quickly for Sydney’s coronial system, however, and by the 1930s the modern facilities of the 1908 Coroner’s Court were considered outdated. Worse was to come – in 1936, the captain of the P&O cruise ship Strathaird complained that his passengers had a direct sight line to the post-mortem room, a rather appalling introduction to Sydney Harbour. Any plans to improve the court were put on hold during World War II, with additions and alterations finally made in 1947. This included the first instance of a refrigerated room for body storage.

New Coroner's Court - Architect's perspective 1967, Report of the Department of Public Works for the Year Ended 30 June, 1967 (Sydney: V.C.N. Blight, 1967), p. 46, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (Q620.09/N)

To better serve the growing Sydney community, and the growing complexities of the legal and forensic world, a new facility was planned on Parramatta Road. Constructed on the old site of a coach-maker’s workshop, the two-storey Glebe Coroner’s Court was officially opened in 1971. The courtrooms, counselling rooms, extra laboratories and offices were located in the top ‘public’ section while the bottom section was the turf of the forensic pathologists, technicians and lab assistants who cared for the deceased. Though all precautions were taken to separate the two floors and their various functions, occasionally the two worlds collided with memorable results. In July 1973, the courtrooms had to be evacuated due to a strong smell coming from the morgue below, after an air-conditioning malfunction caused foul air to be diverted into the courtroom. The Glebe Coroner’s Court was the centre of coronial power in New South Wales from 1971 to 2018, seeing famous cases including the Granville Rail Disaster in the 1970s, the Strathfield massacre of 1991 and the 1995 death of Anna Wood. In 2018, the court was moved to a multimillion dollar complex in Lidcombe. Read Darrienne's entry on the Glebe Coroner's Court here and click through the links to further explore the history of the role of the coroner in Sydney. Darrienne Wyndham is a heritage consultant at Artefact Heritage Services and has recently written a series of essays on the role of the coroner in New South Wales for the Dictionary of Sydney, which were published with support from Artefact & Health Services. She specialises in the interpretation of historic sites, buildings and railway stations. Her research has spanned a wide range of time periods and locations across Sydney, from nineteenth century roads in the eastern suburbs to World War II internment camps in Moorebank. Thanks Darrienne! For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Darrienne & Wilamina here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Fanmail for Mr Bertie

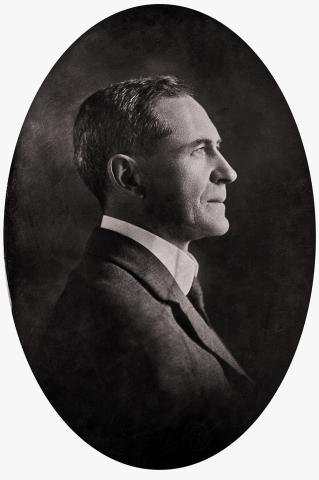

Charles H Bertie, 1925-1927, City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 54/129)

Charles H Bertie, 1925-1927, City of Sydney Archives (NSCA CRS 54/129)

Stories of old Sydney by Charles H. Bertie ; illustrated by Sydney Ure Smith 1912, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (91/137)

Stories of old Sydney by Charles H. Bertie ; illustrated by Sydney Ure Smith 1912, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (91/137)

Dyarubbin

Dorumbolooa, Sackville Reach June 2018, photo by Grace Karskens

Dorumbolooa, Sackville Reach June 2018, photo by Grace Karskens

Most people feel familiar with the Hawkesbury, one of Sydney’s most recognisable rivers, but how much do they really know? Listen to Marika and Wilamina on 2SER here The Hawkesbury River, known as Dyarubbin to local Aboriginal people, was one of the earliest places invaded and colonised when settlers started forcefully taking land along the river from 1794.[1] Resultantly this colonial heritage is celebrated in widespread narratives of the river, overshadowing and sometimes omitting Darug people, perspectives, history and culture, when Darug people have lived on the river for millennia and still live on the river today. The Dyarubbin exhibition at the State Library of NSW is an invitation to traverse the river with four Darug women: Jasmine Seymour, Rhiannon Wright, Leanne Watson and Erin Wilkins and to listen to their stories. They have identified seven special and significant sites along the river ranging from cultural, spiritual and colonial sites to those with little-known stories. The exhibition builds on knowledge and research established by the four Darug women and Professor Grace Karskens in their collaborative project ‘The Real Secret River, Dyarubbin’, which won the State Library of NSW Coral Thomas Fellowship in 2018-19.

First page of John McGarvie's list of 'Native names of places on the Hawkesbury’ 1829, Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales (Reverend John McGarvie papers, 1825-1847, A 1613, Poems and prose, 1825-1835, p25)

First page of John McGarvie's list of 'Native names of places on the Hawkesbury’ 1829, Mitchell Library State Library of New South Wales (Reverend John McGarvie papers, 1825-1847, A 1613, Poems and prose, 1825-1835, p25)

One of the project’s aims is to map and return Aboriginal place names found in a list compiled by Reverend John McGarvie, a Presbyterian minister, in 1829 titled ‘Native Names of Places on the Hawkesbury’, to their river locations. Some of the place names in the list, like ‘Bulyayorang’ (Bulyayurang) which refers to the land over which the town of Windsor was built, had ceased to be used as Aboriginal languages were forcibly and systematically diminished over time. The McGarvie list is on display in the exhibition, showcasing important place names like ‘Dorumbolooa’ (Durumbuluwa) which means ‘zone of the rainbow’ or ‘path of the rainbow,’ which tells part of the story of Gurangatty, the Great Eel creation ancestor spirit for Darug people. Jasmine, Rhiannon, Leanne and Erin take exhibition visitors to one of the resting sites of Gurangatty in one of the deepest parts of Dyarubbin. They say that the water swirling on the water’s surface is symbolic of the Great Eel, which is connected to water, whirlpools and flood power and that the rock engravings of Gurangatty found on the biggest bends of the river tell the story of the Great Eel as visitors pass through Darug Country. Sadly, some of those engravings are situated on what is now privately owned property, and some are said to have been destroyed. The inability of Darug people to access sites along the river dates to the time of invasion, when settlers took prime agricultural land along the river, blocking Darug people from accessing their most vital resource. Darug people, men and women, defended not only their land and livelihoods fiercely, but their culture and spirituality which were - and still are today - intrinsically connected to the river. The Dyarubbin exhibition highlights the importance of truth-telling about the history of the Hawkesbury River region and the need for Darug stories, resilience and culture to be recognised, shared and celebrated. The beautiful Dyarubbin exhibition will be on at the State Library of NSW until 13 March 2022. Visit the State Library website for more information: https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/exhibitions/dyarubbin Read Grace Karskens' entries on the Dyarubbin project on the Dictionary of Sydney. We are grateful for the support from Grace and Rob Thomas which allowed these entries to be published: https://dictionaryofsydney.org/artefact/real_secret_river_dyarubbin_project Explore the interactive map based on the Dyarubbin team's work that has been published by NSW Spatial Services here: https://portal.spatial.nsw.gov.au/portal/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=82ae77e1d24140e48a1bc06f70f74269

Real Secret River: Dyarubbin project team members (l to r) Leanne Watson, Grace Karskens, Erin Wilkins and Jasmine Seymour above Dyarubbin at Sackville June 2018, photo by Paul Irish

Real Secret River: Dyarubbin project team members (l to r) Leanne Watson, Grace Karskens, Erin Wilkins and Jasmine Seymour above Dyarubbin at Sackville June 2018, photo by Paul Irish

Marika Duczynski is a Gamilaraay and Mandandanji descendent with family ties to Moree in north-west NSW. She is a Project Officer in the Indigenous Engagement branch at the State Library of NSW working to amplify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and perspectives within libraries and collections. Marika leads the development and delivery of Indigenous Engagement’s projects across a variety of different priority areas. Recently she curated her first exhibition, Dyarubbin. Notes: [1] Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020, p 129 For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Marika & Wilamina here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

A huge crowd for a hanging: the end of John Knatchbull

Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (923.41/K67/2)

Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (923.41/K67/2)

One of my very favourite letters in the collections of the State Library of NSW was written by a wool merchant by the name of Joseph Whitehead. In an 1838 letter to his uncle in England, Whitehead describes Sydney as ‘without exception one of the most wicked places under the sun [with] murders, suicides, robberies, innumerable pride, hypocrisy, lying, backbiting, drunkenness, and debauchery without end’. A scathing, but not entirely inaccurate, review. Now, crime might have been standard, but a heinous crime still brought the city to a standstill. Listen to Rachel and Wilamina on 2SER here When John Knatchbull murdered Ellen Jamieson, a widowed shopkeeper, at her home in Erskine Street in January 1844 he generated one of the biggest stories of mid-19th century Sydney. Knatchbull was a bloke who, today, we would say is ‘known to police. He was born in England around 1792, and he appeared at the Surrey Assizes in 1824 where he was sentenced to fourteen years for stealing with force and arms. Our man, also known as John Fitch, arrived in Sydney in 1825 and was granted a ticket-of-leave in 1829. He was in and out of trouble however until he received another ticket-of-leave in 1842. He became engaged in late 1843 to a young widow, Harriet Craig, and just before the wedding he realised he needed some cash. Sydney’s The Dispatch reported: It is said that the prisoner was engaged to be married, and that Monday was the day fixed, but that he was not possessed of means to defray the expense of the ceremony. That, with this inducement to his desperate attempt, and having some knowledge of Mrs. Jamieson’s circumstances, he watched for some hours about the neighbourhood, and at midnight, when all was quiet, effected an entrance into the house under the pretence of wanting a pint of vinegar. Then, finding he could not obtain his purpose without proceeding to violence, he struck Mrs Jamieson upon the head several times, with a tomahawk, which was afterwards found in the house, stained with blood—and having laid her for dead, proceeded with his scheme of plunder.

Knatchbull , as he appeared on his trial, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (A923.41/K67/2)

Knatchbull , as he appeared on his trial, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (A923.41/K67/2)

Knatchbull attacked Mrs Jamieson on 6 January 1844, but she didn’t succumb to her wounds until 18 January. When she did die, there were two more orphans in Sydney. People were outraged, and the newspapers were only too happy to oblige a fascination with a man from a noble family who had become a murderer. There was more than a brutal crime to report on when the brilliant barrister Robert Lowe took Knatchbull’s case and tested ideas of insanity for the first time in an Australian court. Lowe passionately argued, in a one-day trial on 24 January, that insanity of the will could exist quite separately from insanity of the intellect, and that Knatchbull had yielded to an irresistible impulse. In short, he could not be held responsible for his crime. Nice try. The members of the jury were not having any of it. In fact, one of the many startling details of this case is that the jury returned a verdict of guilty without leaving the box. No solemn retirement. No careful deliberation. No pretence of considering all the details presented at the trial. Just ‘guilty’. It was all over for Knatchbull, and one of the most famous villains of colonial Sydney met the hangman at Darlinghurst Gaol on 13 February 1844. Sydney, then, was a walking city. To walk from any point in town to Darlinghurst would have been an easy trot. Almost normal. What was not normal on Knatchbull’s last day was that over 10,000 people walked from all over Sydney to watch him hang.

![Police report on John Knatchbull January 1844, State Archives & Records NSW 9/6329, No. 135]](https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/slnsw.dxd.dc.prod.dos.prod.assets/home-dos-files/2021/05/SRNSW-9_6329-no-135.jpg) Police report on John Knatchbull January 1844, State Archives & Records NSW 9/6329, No. 135]

Police report on John Knatchbull January 1844, State Archives & Records NSW 9/6329, No. 135]

Notes ‘Execution of John Knatchbull’, The Australian, 15 February 1844, p.3 accessed 25 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37123826 ‘Inquests’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1844, p.2 accessed 25 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12412784 ‘The Life of John Knatchbull: Executed at Darlinghurst, Sydney, on Tuesday, February 13, 1844, for the Horrid Murder of Mrs Jamieson, Sydney, H. Evers, 1844, State Library of NSW, A923.41/K67/2. ‘Our Weekly Gossip’, The Dispatch, 13 January 1844, p.3 accessed 25 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228250613 Roderick, Colin John Knatchbull: From Quarterdeck to Gallows, Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1963. ‘Supreme Court – Criminal Side’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 January 1844, p.2. accessed 25 May 2021 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12411912 Whitehead, Joseph ‘A Letter to his Uncle Samuel Whitehead’, Sydney, 1 March 1838, State Library of NSW, MLMSS 9895.https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YolgA6Q9 Wilson, Jan ‘An Irresistible Impulse of Mind: Crime and the Legal Defense of Moral Insanity in Nineteenth Century Australia’ Australian Journal of Law and Society, 11 (1995). Dr Rachel Franks is the Coordinator of Scholarship at the State Library of NSW and a Conjoint Fellow at the University of Newcastle. She holds a PhD in Australian crime fiction and her research on crime fiction, true crime, popular culture and information science has been presented at numerous conferences. An award-winning writer, her work can be found in a wide variety of books, journals and magazines as well as on social media. She's appearing for the Dictionary today in a voluntary capacity. Thank you Rachel! For more Dictionary of Sydney, listen to the podcast with Rachel & Wilamina here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning to hear more stories from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Archibald Prize

JF Archibald between 1910-19. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ( P1/2150)

JF Archibald between 1910-19. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ( P1/2150)

The Bulletin, 21 Jul 1921, p34

The Bulletin, 21 Jul 1921, p34