The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Tourism

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Tourism

[media]Sydney has been shaped by tourism, but in a large metropolis where tourist experiences so often overlap with everyday activity, tourism's impact often escapes attention. Urban tourism involves not just international visitors, but people from interstate and regional New South Wales and even day trippers, who all see and use the city differently and are often indistinguishable from locals engaged in leisure activities. The tourist's mental map of Sydney has never been the same as workaday Sydney – the harbour, beaches, city centre, the Blue Mountains and national parks to the north and south loom disproportionately large in the tourist gaze, while vast swathes of suburbia remain invisible.

Definitions

Tourism is defined in various ways, but is perhaps best understood as a phenomenon that emerged in Europe during the eighteenth century, when people who were normally attached by strong ties to a particular location began to take pleasure in travelling by choice outside their usual environment for the sake of what particular places offered: entertainment, society, curiosities, architectural wonders, natural beauty. In other times and in other cultures, people enjoyed travel experiences: other forms of travel – pilgrimages, voyages of exploration, travels for trade or education – could also be enjoyed for the pleasures they provided along the way. Until the eighteenth century however, it was rare for people to travel for the sole purpose of pleasure. When the educational and health justifications of the aristocratic Grand Tour and spa culture gave way to pleasure in the late eighteenth century, tourism was born. Tourism essentially involves travel for the pleasures on offer, rather than for economic, spiritual, health or educational reasons, although it is often difficult to separate the strands. It expanded when more and more people acquired identifiable leisure time and sufficient disposable income to enjoy it.

Thus while Aboriginal Australians were always great travellers and enjoyed their travels – crossing their country back and forth on what became known to European settlers as 'walkabout' was an essential part of their being – it would be inappropriate to think of their travels as tourism. Different Indigenous groups from far and wide visited the Sydney basin for a variety of spiritual and economic reasons, but without sharp distinctions between leisure and work, and without a fixed sense of 'home' to escape from, they were not tourists. Ironically, Aboriginal visitors to Sydney harbour might have only become tourists when they travelled to Sydney for the sake of being amused by the antics of the very strange people who had arrived in 1788.

Convict society before 1850

On the other hand, those Europeans who established the convict settlement at Sydney were a product of the very time and place that saw tourism emerging. None of them were tourists either – all were expected to work, many looked to how they could turn a profit, and the convicts, of course, had no choice in their travel. Yet the forces that were creating tourism on the other side of the world were also touching them. It can even be argued that Joseph Banks, who had seen his voyage to the Pacific with Cook in 1770 as an alternative to a Grand Tour and in many ways a pleasure excursion, brought a tourist's eye to his influential promotion of Botany Bay as a site for a convict settlement. [1]

Once the First Fleet landed and they looked around them, the officers at least could adopt a 'tourist gaze'. The attractiveness of Watkin Tench's journal to the modern reader derives from his enthusiastic tourist's perspective: he had an eye for the curious and a willingness to be entertained. And even in 1788, George Worgan was indulging his 'Inclination to ramble' into the bush, perhaps qualifying as Australia's first European 'bushwalker'. [2] Many of the names they bestowed on the Sydney area evoked places they knew in Europe that had established tourist credentials: Brighton, Cheltenham, Rydalmere, Ramsgate, Clovelly, Cremorne, Queenscliff, Clontarf, Como, Engadine, Longueville, Sylvania, Vaucluse, Lugarno, Pyrmont, Sans Souci. Other names suggested the tourist perspective: Bellevue Hill, Riverview, Fairview, Bayview, Seaforth. [3]

The new arrivals also examined the locals with the gaze of tourists, at least initially: later the tourist's curiosity would give way to the colonist's more destructive desires. [4] They collected souvenirs: indeed such was the 'rage for curiosities' that the theft of Aboriginal spears and tools caused ill-feeling (though it seems it was World War I that gave rise to the peculiarly Australian use of the verb 'souvenir', meaning to thieve or pilfer [5]). It was not long before local people were manufacturing artefacts or performing corroborees specifically for the entertainment of the intruders. Captain Hunter watched a corroboree within two years of the First Fleet's arrival:

They ... would apply to us for ... marks of our approbation of their performance; which we never failed to give by often repeating the word boojery. These signs of pleasure in us seemed to give them great satisfaction.

It was, he said, 'well worth seeing'. [6] It was also, in the commoditisation of Indigenous culture, indicative of the uneasy relationship that tourism would continue to have with imperialism into the twenty-first century.

Perhaps what most struck the tourist in the colonist was the harbour. It was of course a working harbour – a transport artery, a source of food, a means of defence. Governor Arthur Phillip's famous comment – 'one of the finest harbours in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line might ride in perfect security' [7] – was the response of a naval strategist with an imperialistic perspective. But soon there were expressions of delight. After he arrived in 1810, Governor Macquarie had convicts carve a seat for his wife at her favourite spot to view the harbour, Mrs Macquarie's Chair. As we will see, while other tourist sights rose and fell in the tourist's estimation over the centuries, the harbour would remain the focus of tourist Sydney: for Geoffrey Moorhouse, writing his account of Sydney for the Olympics in 2000, the harbour was still 'the key to Sydney, its alpha and its omega'. [8] Water sports, regattas and picnics around the harbour were popular pastimes for all classes but perhaps more for the elite, for whom a romantic appreciation of natural beauty was becoming a test of sensibility, on their carriage trips along South Head Road (built in 1811), or their visits to the villas that began to take advantage of views. [9] They almost immediately applied the new language of the 'picturesque' and the 'sublime' to the harbour and these words continued as tourist clichés long after they were drained of meaning.

For convicts the town itself offered more in the way of pleasure. Though they were forced labour, the convicts came to have a definite sense of their rights to leisure. [10] Particularly for those convicts who were assigned away from the main settlement, as for their masters, the growing town, with its taverns, theatres, gambling dens, shops and brothels, provided escape from the drudgery of hard labour. Even for convicts, a trip to town could look like a holiday: Gregory Blaxland complained that after the Sunday muster – their one day off – they 'resorted to houses of ill-fame and drinking, not returning to their master until night or the following day'. [11] The attractions of Sydney also appealed to female convicts: 'All they want is to get down to Sydney and … dress themselves up and go to the flash houses, and at night to the dancing houses, and then they are happy.' [12] The delicate balance between the natural beauty of the harbour and the excitement generated by a growing urban centre would be the dominant element in Sydney's tourism history.

Infrastructure

As the town grew, it catered increasingly for visitors, including tourists. Basic inns gave way to notable hotels, culminating in the opening of the Hotel Australia in 1891, alongside less pretentious guest houses and lodgings. Probably a majority of visitors stayed with family and friends. At the same time, the development of dependable, regular steamship services and the emergence by the 1880s of a widespread Sydney-centric rail network ensured Sydney became a focus for visitors, some from overseas but more from other colonies or from up the country, many of course on business. One significant drawcard was the Easter Show (Royal from 1891), created when the Royal Agricultural Society moved its annual competition to the showground at Moore Park, where it remained until 1998. [13] By 1907 the Sydney Morning Herald was noting that the Easter Show was attracting 'many thousands of ... hard working folk on the land' to Sydney for their yearly holiday. [14] The hotels, the big steamship companies such as Burns Philp, and the government-owned railways became the dominant tourism promoters. Thomas Cook – the company which was most associated with the development of mass tourism in mid-nineteenth-century Britain – had established an office in Sydney and published a guidebook to New South Wales by 1895. [15]

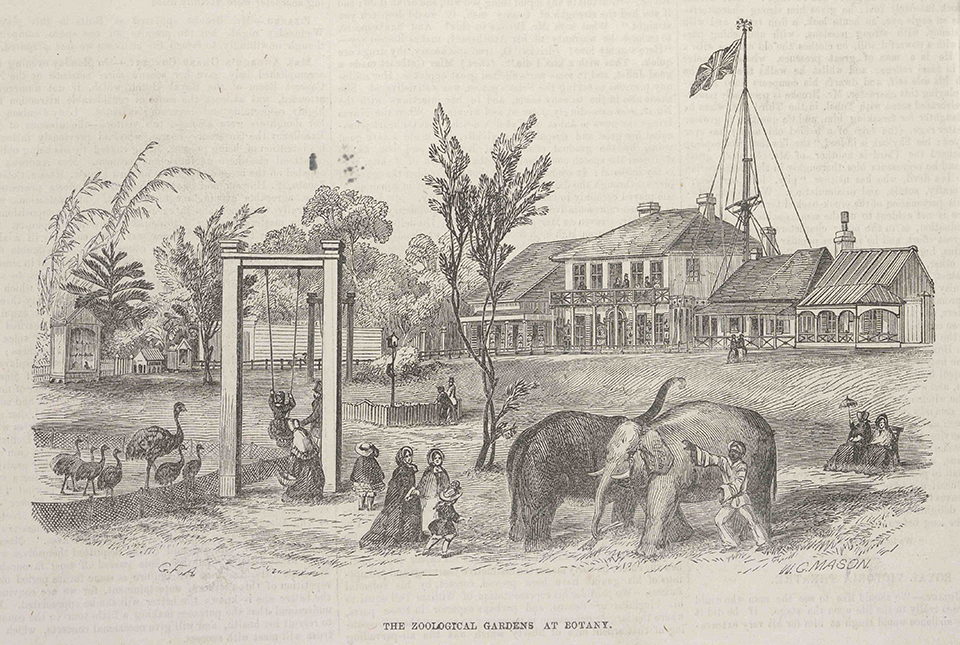

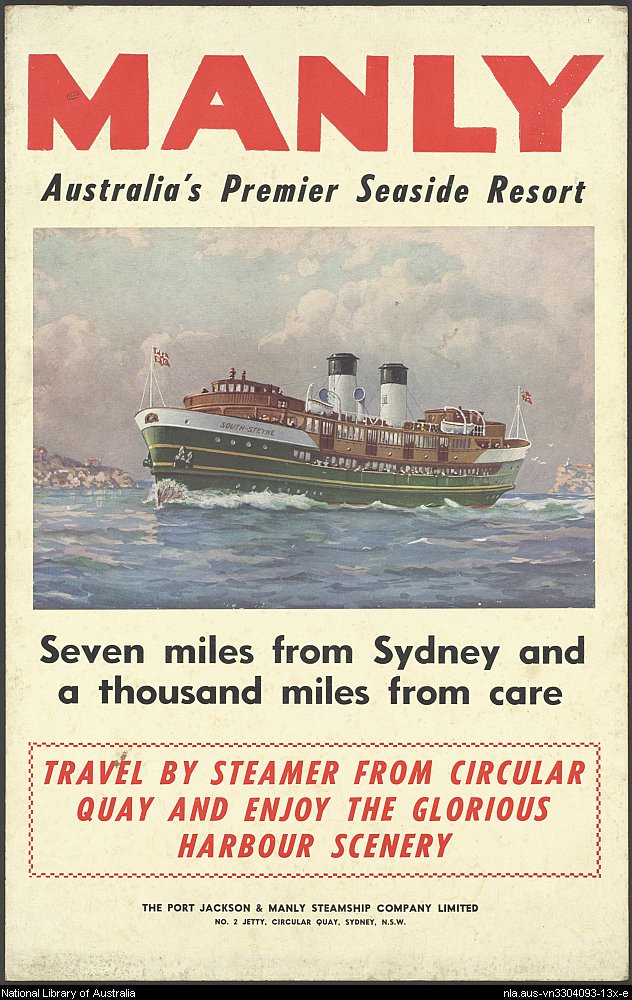

In [media]this we can see the beginnings of tourist infrastructure. Seaside 'resorts' on the English model began to spring up, though they catered more for day trippers. From the 1840s Botany Bay boasted the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel, which had various attractions for holiday-makers including pleasure grounds, dancing, sporting fixtures and by 1850 a zoo. Cremorne Gardens were opened in 1856 – 'among the best of those places of a holiday resort of a superior order in Sydney'. By the 1870s, Balmoral, The Spit, Athol Gardens, Clontarf and Clifton Gardens had followed suit. Watsons's Bay, Mosman's Bay and Chowder Bay were also popular ferry rides: ferries had turned from being merely commuter craft to pleasure craft, and introduced tourist services on weekends. After the Harbour Bridge made a number of large ferries redundant in 1932, they were converted into 'showboats' which survived until 1963. [16] The most ambitious development was Henry Gilbert Smith's scheme from 1853 to turn Manly into 'the Brighton of the South', with residential developments and accommodation for holiday-makers: Manly would long be a favourite holiday destination for country people. [17] Ferry [media]advertising promised that Manly was 'Seven Miles from Sydney and a thousand miles from care', marking it out as a leisure destination. [18] These harbour resorts, with their easy access by ferry or tram from Sydney's most densely populated suburbs, allowed Sydney's workers to become tourists on their days off. Leisure time was gradually increasing for ordinary workers: the 1909 Royal Commission into the Saturday Half Holiday noted the importance of allowing workers more leisure time, and authorities noted the 'unmistakable tendency on the part of local residents to see the beauty spots of their own State'. [19] At the same time there was concern about the presence of 'larrikins' at these harbour resorts. The new Sydney Bulletin made its name in 1881 with a lurid account of a larrikin 'orgy' at Clontarf and the libel case that ensued.

Attractions were piled up at the ocean beaches, as cheap tram travel brought them within reach: aquariums, swimming baths, zoos, sideshows, amusement rides and pleasure grounds were provided at Coogee and Bondi. Judy, the famous protagonist of Ethel Turner's Seven Little Australians, summed up the fun on offer: 'skating, boats, merry-go-round, switchback threepence a go!' [20] Wonderland City at Tamarama opened in 1906, and 1928 saw the opening of Coogee pier, although it was demolished in 1934 after being damaged by heavy seas. Manly Fun Pier was opened in 1931, one of the many attractions built by The Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Company to encourage patronage on its run to Manly. Few of the fun piers and amusements grounds survived long into the twentieth century, unlike their English counterparts, partly because beach culture began to take a different trajectory in Sydney. Sydney's beaches were local amenities used regularly by a relatively small population rather than holiday destinations used sparingly by a large one. The result was that elaborate man-made attractions soon palled for regular visitors, who were not trapped at resorts during bad weather and who were primarily interested in the beaches' natural (and freely available) attractions of sun, sand and surf. [21] Even in 1883 Richard Twopeny preferred Sydney's attractions because they were 'rather natural than artificial', a primitivism that seemed to many to be reflected in the Aboriginal names of Bondi, Coogee, Maroubra, Narrabeen, Bilgola, and Cronulla.

Once regulations made surf-bathing acceptable after 1902, and surf lifesavers made it safe from 1908, Sydney's beach culture flourished. It represented an evolving balance between the formality of the seaside resort and the natural appeal of the romantic landscape, though some beaches were also 'improved' regularly. Bondi's pavilion and Marine Parade were products of the 1920s. [22]

The tourist gaze

The sense that Sydney was a collection of tourist sights was reinforced by the postcard boom of the late nineteenth century. Local photographers such as Charles Kerry and WH Broadhurst provided tourist images of Sydney's beauty spots and significant buildings. While postcards were simply a popular form of communication, not limited to tourists, they contributed to the process by which a 'tourist gaze' and self-consciousness about how the city looked permeated everyday life. Guidebooks too gradually packaged the city for consumption, turning the city into a convenient list of [media]sights to be ticked off. [23] James Waugh published the first local guidebook, The Stranger 's Guide to Sydney, in 1858, and others by Maddock, Fuller's, Gibbs Shallard and Dymock's followed. Many of the hotels, Pfahlert's, the Grosvenor, the Metropole, Aarons, the Empire, Tattersall's and the Wentworth, had produced their own guides by the end of the century, all freely borrowing from each other, alongside the elaborate guides produced by the New South Wales Railways. Then from 1905 the newly established New South Wales Government Tourist Bureau began producing tourist guidebooks.

The harbour remained the focus of the tourist gaze. Sydneysiders' pride in 'our 'arbour' became a running joke among foreign visitors and locals, who nevertheless also sang its praises. The much lionised Anthony Trollope, who visited in 1871, would write

I despair of being able to convey to any reader my own idea of the beauty of Sydney Harbour. I have seen nothing equal to it … It is so inexpressibly lovely. [24]

The praise would be much quoted; his warnings about the habit of boasting were heeded less. [25] The more formal setting of the Botanic Gardens – they had it on Trollope's authority they 'beat all the public gardens I ever saw … impossible not to love' – were also admired by overseas visitors. They were still a 'miracle of tranquillity' in 1999. [26] Another attraction that made the most of its setting was the zoo, which was moved from Moore Park to its harbourside setting at Taronga in 1916.

But it was not just the harbour and its natural setting. The busyness of ferries and sailing boats, the industry and the growing town also attracted comment. Over time there was a shift from seeing the city as a triumph of British imperialism to looking on it with national pride: Trollope and others were quoted less and there was more conviction of its 'world renown'.[27] The praise was not unanimous: Richard Twopeny was 'quite angry' that the town was 'so unworthy of its site', [28] but Mark Twain – who brought a tourist's eye to his visit in 1895 – was more generous. He wrote that the harbour

would be beautiful without Sydney, but not above half as beautiful as it is now, with Sydney added … The city clothes a cluster of hills and a ruffle of neighbouring ridges with its undulating masses of masonry, and out of these masses spring towers and spires and other architectural dignities and grandeurs that break the flowing lines and give picturesqueness to the general effect. [29]

For international [media]visitors, the harbour and the relationship between nature and culture was generally Sydney's great attraction, but international tourists were a minority. Most tourists were Australian: for many of them Sydney was the largest city they would ever experience, and so, while enjoying the natural amenities, it is probable that the metropolitan and cosmopolitan attractions of Sydney were always the greater source of wonder. For tourists from Melbourne, on the other hand, the tourist experience was constantly seen through the prism of the rivalry between Australia's two largest cities, and the factors that most differentiated them – climate, town planning, the harbour – were the focus, for better or worse.

Aboriginal tourist attractions

As part of the effort to make Sydney modern, surviving Aboriginal inhabitants who congregated at Bennelong Point were removed to the reserve at La Perouse at the end of the nineteenth century. Officially day trippers to La Perouse were prohibited from entering the Aboriginal Reserve. With the opening of a tram terminus at La Perouse in 1902 however, the area increasingly began to attract tourists, who came not only for a trip to the seaside but also for the 'fascination of looking at the Aborigines'. [30] The Aboriginal residents quickly developed their own tourist economy, making boomerangs, shields, shellwork and other souvenirs, charming snakes, the children diving for coins. For many visitors they represented a baseline of 'primitivism' against which Sydney's 'progress' could be measured, but there they had some control over how their culture was put on display for tourists. [31]

National parks

[media]The balance between nature and culture can also be seen in two significant tourist events of 1879. That year saw the proclamation of Sydney's 'National Park' (later, following the visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, the Royal National Park), generally accepted as the world's second national park, after Yellowstone. In 1894 Sydney acquired a second, Ku-ring-gai Chase, to the north. These large expanses of relatively untouched bushland were intended to provide 'a national domain for rest and recreation' for 'the jaded citizen of Sydney or her suburbs'. [32] The tourism they provided was democratic. They were much larger than the recently conserved Hampstead Heath for example, and much more convenient to a large population than Yellowstone. Being easily accessible by rail (National Park station was opened in 1886) meant rejuvenation in a bush setting was a possibility for 'the people'. And the people came: in 1903, there were 170,000 visitors to the National Park. Lane Cove National Park was opened in 1938. Attempts to 'over-develop' the parks were resisted through the twentieth century: the attraction was quiet recreation – picnics, boating, walking – immersed in a romantic natural setting. The natural landscape around Sydney – its wattles, Christmas bush, angophoras, lilies and Port Jackson figs – was increasingly understood as something to admire.

The International Exhibition

[media]If nature in its most primitive state was the attraction in national parks, then modern industry was the attraction at the Sydney International Exhibition, also opened in 1879, the ninth since the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London's Crystal Palace. Housed in the magnificent Garden Palace, a technological feat in itself with the world's sixth largest dome, it displayed products, art and technological innovation from around the world. It attracted over 1,100,000 visitors (the Australian population was about 2,200,000), mostly local, though its international significance led to a consciousness that Sydney was being put on display. The organisers were anxious to emphasise Sydney's modernity to the world, and the progress achieved in less than a century of what they fondly called 'civilisation'. The exhibition building itself, constructed in just eight months, contained Australia's first hydraulic passenger lift in its north tower, where the view over the harbour with still remnant pockets of bushland was a lesson in nineteenth century progress. [33] A modern tram service was built to link the exhibition directly to the hub of the rail network at Redfern. Perhaps Sydney's greatest pride lay in having its exhibition one year before Melbourne's.

[media]The exhibition can be thought of as the beginning of 'event tourism' in Sydney, though sporting fixtures were already proving popular tourist draws. A desire to cater for the exhibition visitor had stimulated many of the guides to Sydney. Sydney would also prove a focus for later events in which the city performed for visitors: the Centennial celebrations of 1888, the Federation proclamation in 1901, the visit of the American 'Great White Fleet' in 1908, the Sesquicentenary celebrations in 1938, the 1988 Bicentenary and then, the biggest of them all, the 2000 Olympic Games. [34]

Viewpoints

[media]The Garden Palace was the city's tallest building and also arguably Sydney's first recognisable man-made tourist sight but it did not survive long: a spectacular fire destroyed it in 1882. Other tall structures (as well as balloon rides) catered for the tourist's desire for a high vantage point: the town hall of 1878, the General Post Office clock tower completed in 1887 (clock and bells installed 1891) and Central Station (opened in 1906 but not acquiring its clock tower until 1921). In 1939 the city's tallest structure, the AWA tower, also had a viewing platform. But none of these modern structures quite had the impact of the Harbour Bridge, which became a popular tourist icon as the world's widest and heaviest steel arch slowly materialised in the 1920s. Its opening in 1932 attracted attention around the world and the government took the opportunity to publicise Sydney's other tourist attractions – the harbour, the surf beaches and the zoo – as if it were inevitable the bridge would surpass them all. [35] In providing such a recognisable symbol of modernity, the bridge not only cemented the harbour as Sydney's premier tourist site, but cemented Sydney as Australia's premier tourist city. As all tall structures must, the bridge too provided a viewing platform. The Pylon Lookout became a major tourist attraction, again offering magnificent views of the harbour along with pride in visible progress, especially as buildings began to edge upwards. It lost popularity once Sydney's first skyscraper, the AMP building, was opened in 1961, with its own viewing platform.

Touring the past

The flip side of Sydney's self-conscious modernising was the beginnings of an interest in Sydney's past (or a particular version of the past) as an object of the tourist gaze. Some monuments were erected early – in 1822 Barron Field had arranged for a plaque to commemorate Captain Cook's landing place at Botany Bay, and in 1870 an obelisk was erected on the site [36] – but it was only in the late nineteenth century that the past began to be seen as of tourist interest more generally. Though it remained a distinctly minority interest, visits to older districts such as Parramatta, Richmond and Windsor began to be valued as a way to see the 'antiquities' of the colony. [37] In 1901 the Royal Australian Historical Society was established. It produced a series of postcards of, and conducted excursions to, historic sites from 1903 [38] and campaigned for preservation of historic houses. Vaucluse House was resumed by the government in 1910 and began to be opened to tours – especially school children. [39] In the 1920s Hardy Wilson and Sydney Ure Smith established an honourable tradition, later taken up by Sali Herman, Unk White and Cedric Emanuel, of producing sketches and etchings of Sydney's fast disappearing historical fabric. By the 1920s there was a well-established understanding that parts of Sydney were 'quaint', 'charming' and 'old-world', particularly those with vestiges of a Georgian past: both inner suburbs with higgledy-piggledy streets and Macquarie's 'five towns' on the fringe, which began to attract motor tourists in search of historical sites. [40] However the growing interest in the past competed with the inexorable desire to be modern. Many significant buildings were razed in the name of progress – despite campaigns such as those around Burdekin House in 1922 (demolished 1933) and St Malo from 1948 (demolished 1961). [41]

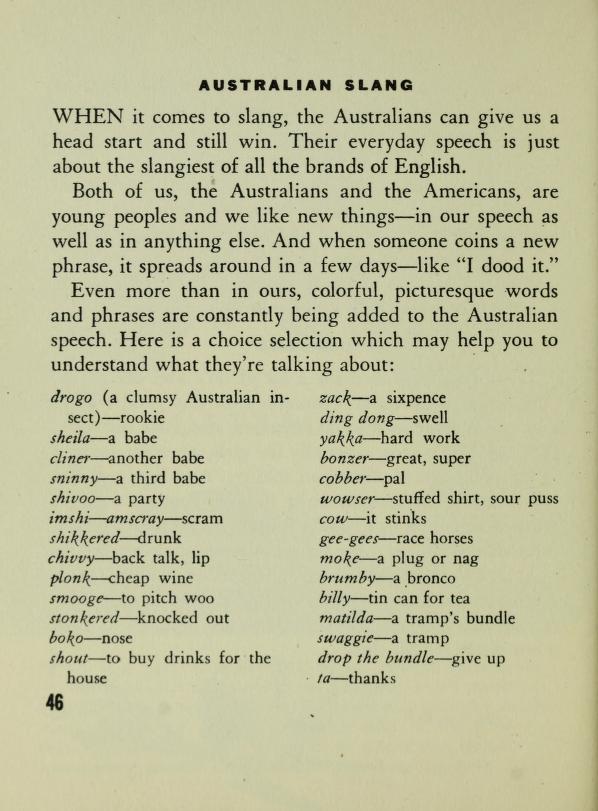

[media]With the outbreak of war in 1939 and increasing rationing and travel restrictions, conventional tourism diminished. No more potent symbols of the war's seriousness were the appearance of barbed wire on that tourist icon, Bondi Beach, and the dismantling of the GPO clock tower. However the war also gave tourism a boost with the presence of soldiers in Sydney looking for things to do: in particular the arrival of large numbers of American troops from 1942 on their way to the front. They represented the largest contingent of foreign visitors Sydney had seen, and in catering for their tourist needs, in everything from the provision of guides and the increased worldliness of taxi drivers to the relaxation of drinking laws and the consolidation of Kings Cross as a brothel district, Sydney was subtly reshaped to cater to the international tourist. [42]

Postwar international tourism

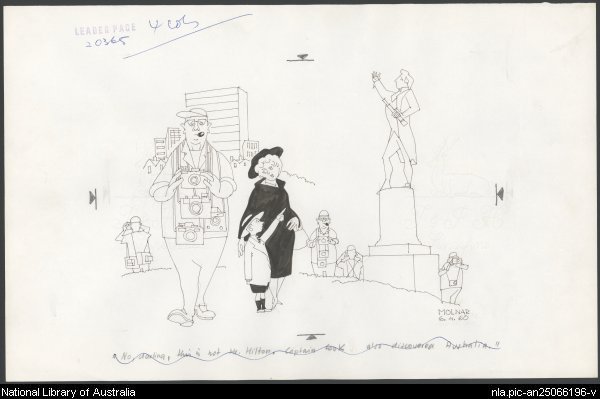

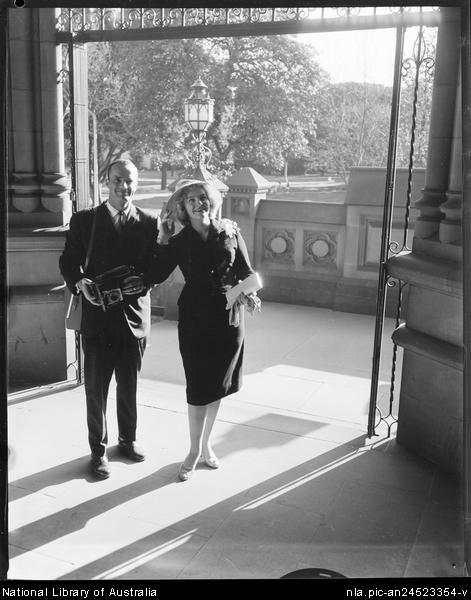

Despite the [media]best efforts of tourism promotion, both public and private, international tourism had never been a major feature of tourist Sydney. However with postwar affluence, the rise of air travel and a world-wide tourism boom, inbound tourism increased significantly. In the space of a 60-year period the number of international visitors to Australia grew from 43,692 in 1950 to over 5.9 million by 2010. Of those, about 2.7 million visited Sydney, making it Australia's top tourist destination. [43] Sydney's international profile gradually developed during this period, flourishing in the first decade of the twenty-first century as the city regularly began to feature in 'top ten' lists of the world's best cities and most desirable travel locations. [44] [media]While initially Sydney benefited from being the 'gateway' to an Australia promoted largely for its outback, natural features and, especially following a major 1965 report by Harris, Kerr, Forster, its Aboriginal heritage, increasingly Sydney itself was promoted as a destination in its own right, a crucial element in its transformation into a 'world city'. Where industrialisation was the sign of modernity in the early to mid twentieth century, by the 1970s there was a developing sense that modernity was judged by how well a city catered for international tourists.

R and R

Three important changes took place in the 1960s and 1970s in the way Sydney appeared to the world. The positioning of Sydney as a destination for about 300,000 American troops on 'rest and recreation' (R & R) during the Vietnam War created a ready-made tourist market that had to be catered for. [45] Kings Cross had already become a cosmopolitan and artistic hub, but the American presence marked it out as a particular tourist precinct – the city's red light district – and considerably boosted the illegal drug and prostitution businesses. The very obvious presence of this influx of tourists encouraged ordinary people to become more conscious of themselves and their city as an object of a tourist gaze. [46]

History tourism

Also important was a widespread discovery of Sydney's past. Perhaps the crucial turning point was the Rocks, which was earmarked for a massive redevelopment until the Builders' Labourers Federation imposed a 'green ban' in 1971, in the interests of both heritage and the local community. It too was turned into a tourist precinct, with a 'pleasant, if haphazard process of rustication' ironically displacing its old reputation for crime and disease. [47] The initial attempts to market it to families as 'the birthplace of the nation' were less successful than a later combination of backpacker and upmarket food and retail tourism, which eventually attracted 14 million visits a year and proved as much of a threat to the local residents as office towers. The charms of Paddington's 'iron lace' had already been discovered and were attracting tourists as much as home-buyers.[media] In 1986 the Queen Victoria Building was reopened after extensive restoration and refurbishment as a 'high-quality retail centre in a restored Victorian setting', and it too was a favourite with tourists. The 1898 building was in danger of demolition in 1959, when it was widely seen as a Victorian monstrosity, but was saved by the city council's 1971 Strategic Plan, which recognised the value of the city's historical fabric. The QVB was always meant to be a shopping centre. More controversial redevelopments were the 1985 InterContinental Hotel in the 1851 Treasury building and the 1999 Westin Hotel in the 1874 General Post Office building, where the original uses of the buildings were erased in the interests of up-market tourism. Other areas that became popular as tourist precincts depended on their heritage being saved: Glebe, Balmain, 'bohemian' Newtown, Surry Hills and Woolloomooloo (most of them subject to Green Bans). Yet at the same time rapidly expanding suburbia swallowed up the historic towns of Parramatta, Liverpool and Campbelltown, once enjoyed by those heading out of the city for a Sunday drive in search of 'old world charm'. Other suburbs attracted tourists because of the character bestowed on them by particular migrant groups: Leichhardt's Italians or Cabramatta's Vietnamese. The most extreme example of such a precinct is Chinatown, which had attracted tourists from the late nineteenth century but was thoroughly made over as a tourist precinct in 1980: lion gates and ceremonial arches gave an instantly recognisable and internationally acceptable 'traditional' notion of Chineseness to Dixon Street. [48] These areas remained vibrant local communities despite the tourists. [49] But whose past was being saved? A historical past that was not readily apparent in an aesthetically pleasing building or streetscape was often ignored. [50]

New attractions

Perhaps the most dramatic contribution to tourism was the advent of a determinedly modern building that was a dramatic break with the past: the Sydney Opera House. It initially gained international attention because of the controversy surrounding its construction but once it was opened in 1973 it became an enormously potent symbol of Sydney internationally, one of the world's most recognised and admired buildings. [51] Every tourist had to have their Opera House moment. As a member of the American indy band No Age put it, 'It really does feel like you are hanging out in a postcard'. [52]

Despite the tourism boom, purpose-built tourist attractions, often with significant government funding, tended to struggle as had the old beachside amusement parks. Old Sydney Town opened in 1975 and closed in 2003; Australia's Wonderland survived from 1985 to 2004; Fox Studios opened in 1998 but its theme park element closed down in 2001. The one survivor was Luna Park, which had opened in 1935 under the Harbour Bridge and survived, sometimes precariously, largely because it came to generate affectionate nostalgia as a heritage site.

The development of wildlife-focused tourism attractions was more successful, perhaps because they catered to those tourists, both international and domestic, with a desire to see something of the 'real' Australia without having to go too far from the comforts of the city. The first of these parks were built on the outskirts of Sydney, taking tourists out of the city centre and into the suburbs. In the west, Koala Park Sanctuary opened in 1930 and Featherdale Wildlife Park in 1972. The conservation and educational aims of both parks were funded by tourists' desire to 'cuddle, pat and get a photo' with a koala or kangaroo. [53] To the north, at the very limits of the Sydney metropolitan district, the Australian Reptile Park opened in Gosford in 1958 (in 1993 it moved to Somersby, near Old Sydney Town). [54] However, the ability of the suburban parks to entice tourists out of the central district was challenged in 2006 with the opening of Sydney Wildlife World, an enclosed and air conditioned facility boasting around 6000 animals, in the heart of the tourist district of Darling Harbour. Its opening illustrated the long running and ongoing struggle of tourism attractions in the outer suburbs to compete with the heavily marketed, developed and well-funded inner city.

The Sydney brand

But in [media]other ways the lived city itself was made over to tourism as manufacturing declined and the meaning of the city shifted from a place of work to a place of pleasure and spectacle. [55] Sydney became a 'brand' to be sold to tourists. This represented a move away from the marketing strategies of the late 1980s and early 1990s where Sydney was presented as a gateway to New South Wales and Australia: 'Tourists come to see Sydney and travellers go beyond', declared a 1992 Australian Tourism Commission brochure distributed throughout Asia. [56] The 1990s saw the Tourism Commission of New South Wales (later Tourism New South Wales) alternate between promoting regional tourism and emphasising Sydney, ending the decade with a strong focus on Sydney for New Year's Eve 1999 and the 2000 Olympic games. [57] In the first decade of the new millennium, 'brand' Sydney was heavily promoted by Tourism Australia and Tourism New South Wales both internationally and domestically in a series of campaigns: in 2004 'There's no Place in the World like Sydney', in 2007–08 'City of Celebrations', in 2009 'Vivacity' and, in 2010, 'Sydnicity', a word devised by Tourism New South Wales to describe, 'the unique combination of natural beauty, vibrancy and energy that can only be found in Sydney'. [58]

With more than 125,000 tourism-related businesses located in the Sydney region by 2009/10, tourism had remade the city in all sorts of ways; [59] new structures were built around spectacle, festivity and consumerism, with tourists in mind. Tourism was also used to justify changes to more 'flexible' working conditions, especially for hospitality workers, to shopping hours and to licensing laws and an advertising campaign encouraged Sydneysiders to smile at tourists. Festivals too were developed with an eye to the tourism market. The old Waratah Festival disappeared and the month-long Sydney Festival arrived, to be further expanded with food and wine festivals throughout the year including the Sydney Good Food & Wine Show launched in 2002, followed by the Crave International Food Festival in 2010. The Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras developed from a protest march in 1978 to a major tourism event by the 1990s, attracting large numbers of interstate and international visitors keen to follow the advice of the Bruno Gmünder gay travel guide, which declared it to be 'an absolute once-in-a-lifetime must for every gay travelling man'. [60]

Postmodern tourism

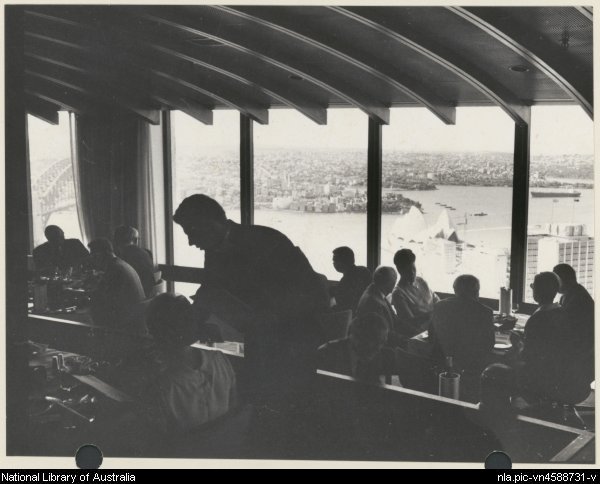

Perhaps the first indication of a new postmodern aesthetic was Sydney Tower (Centrepoint), opened in 1981 as 'The Eiffel Tower of the Southern Hemisphere' and a sign that Sydney was now a 'world-city'. Its explicit, self-reflexive celebration of tourism turned Sydney residents into 'citizen-tourists' who, alongside foreigners, gazed at their city and themselves. [61] The last goods train left Darling Harbour in 1984, and the whole precinct was transformed from 'derelict docklands to sparkling international playground' for the 1988 Bicentennial celebrations, and a host of attractions were added: the Entertainment Centre, the convention centre, the Chinese Garden, Sydney Aquarium, IMAX, the casino, Cockle Bay Wharf and lots of shopping. In 2011 a portion of Darling Harbour was ‘rejuvenated’ and relaunched as ‘Darling Quarter’; the area, containing the city’s largest public playground, was described as both a ‘community precinct and tourist destination’, again contributing to the blurring between local and tourist. [62] Major museums, the Powerhouse and Maritime Museum, were developed: museums always balanced their research, educational and entertainment roles but they became increasingly judged by their capacity to attract tourists. The controversial monorail, also opened in 1988, was seen by its detractors as turning the centre of the city into a tourist theme park. The 'working harbour' had gradually been giving way to a 'leisure harbour' for more than a century. [63] Captain Cook Harbour Cruises was established in 1977 and the last container terminal closed in 2008, to make way for the Barangaroo development. Ever more elaborate ways of entertaining and profiting from tourists were devised. In 1998 Bridgeclimb began and was a phenomenal success, attracting nearly 2 million climbers in 10 years. Sydney Tower skywalk opened in 2005.

Sydney has welcomed tourists with, as Germaine Greer put it in 1982, 'open arms and parted thighs'. [64] In catering for tourism, the city can be changed for better and for worse: the interests of locals and visitors can overlap in the provision of better transport and public spaces, the protection of natural and cultural heritage and generally creating a liveable city. But it can also create a somewhat unreal place alien to those who have always lived in it. The balance is always a tricky one.

Notes

[1] Richard White, On Holidays: A History of Getting Away in Australia, Pluto, Melbourne, 2005 (with Sarah-Jane Ballard, Ingrid Bown, Meredith Lake, Patricia Leehy and Lila Oldmeadow) pp 14–15

[2] Melissa Harper, The Ways of the Bushwalker: On Foot in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007, p 3

[3] Richard White, On Holidays: A History of Getting Away in Australia, Pluto, Melbourne, 2005 (with Sarah-Jane Ballard, Ingrid Bown, Meredith Lake, Patricia Leehy and Lila Oldmeadow) pp 19–20

[4] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text, Melbourne, 2004

[5] W S Ramson (ed), The Australian National Dictionary: A Dictionary of Australianisms on Historical Principles, Oxford, University Press, Melbourne 1988, p 613

[6] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island… John Stockdale, London, 1793, pp 194–5, 213

[7] Arthur Phillip, The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, John Stockdale, London, 1789, p 47

[8] Geoffrey Moorhouse, Sydney: The Story of a City, Harcourt, New York, 1999, p 6

[9] Clive Faro, '"To the lighthouse!" The South Head Road and place-making in early New South Wales', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, December 1998

[10] Graeme Davison, The Unforgiving Minute: How Australians Learned to Tell the Time, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1993, pp 16–20

[11] cited in Richard White, On Holidays: A History of Getting Away in Australia, Pluto, Melbourne, 2005 (with Sarah-Jane Ballard, Ingrid Bown, Meredith Lake, Patricia Leehy and Lila Oldmeadow) p 30

[12] cited in Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture since 1788, Longman, Melbourne, 1995, p 22; see also Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp 180–182

[13] Brian Fletcher, The Grand Parade: A History of the Royal Agricultural Society of New South Wales, RAS, Sydney, 1988

[14] 'The Easter Holiday', Sydney Morning Herald, 23 March 1907, p 12

[15] Julia Horne, The Pursuit of Wonder: How Australia's Landscape was Explored, Nature Discovered and Tourism Unleashed, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2005, pp 58, 139; Jim Davidson and Peter Spearritt, Holiday Business: Tourism in Australia since 1870, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 67

[16] John I Richardson, A History of Australian Travel and Tourism, Hospitality Press, Melbourne, 1999, p 119

[17] Leone Huntsman, Sand in our Souls: The Beach in Australian History, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2001, pp 37–43; Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly, Manly Council, Sydney, 2001; Paul Ashton, 'Inventing Manly 1853–90', in Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, New South Wales University Press in Association with the Sydney History Group, 1987, pp 149–168

[18] Anthony M Prescott, 'The Manly Ferry: A History of the Service and its Operators, 1854–1974', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1985; 93/312/13 Display card, advertising, 'Manly, Australia's premier seaside resort', cardboard, Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Co, Australia, 1940–1950, Powerhouse Museum Collection, http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=133677&search=transport&images=&c=&s=1, viewed 27 April 2011

[19] Peter Spearritt, State of Play: 100 Years of Tourism in New South Wales, 1905–2005, Sydney, Tourism New South Wales, 2005; 1911 Annual Report of the Immigration and Tourist Bureau, p 9

[20] Ethel Turner, Seven Little Australians, Puffin Books, Melbourne, 2001 (1894), p 32

[21] Caroline Ford, 'The battle for public rights to private spaces on Sydney's ocean beaches, 1854–1920s', Australian Historical Studies, vol 41, no 3, 2010; Caroline Ford, 'A summer fling: the rise and fall of aquariums and fun parks on Sydney's ocean coast 1885–1920', Journal of Tourism History, vol 1, no 2, 2009, pp 95–112

[22] Caroline Ford, 'Gazing, strolling, falling in love: culture and nature on the beach in nineteenth century Sydney', History Australia, vol 3, no 1, 2006; see also Caroline Ford, 'The First Wave: the Making of a Beach Culture in Sydney, 1810–1920', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2008

[23] Sascha Jenkins, 'Sydney Harbour: a leisure landscape, in Lynette Finch and Chris McConville (eds), Gritty Cities: Images of the Urban, Pluto, Sydney, 1999, pp 201–216; see also Sascha Jenkins, 'Our Harbour: a cultural history of Sydney Harbour 1880–1938', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2004

[24] Anthony Trollope, Australia and New Zealand, London, 1873, vol 1, p 25; see also Sascha Jenkins, 'Our Harbour: a cultural history of Sydney Harbour 1880–1938', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2004 p 207–08; Ian Hoskins, Sydney Harbour: A History, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 2009, p 169

[25] Anthony Trollope, Australia and New Zealand, London, 1873, vol 1, p 387

[26] Geoffrey Moorhouse, Sydney: The Story of a City, Harcourt, New York, 1999, p 107

[27] Sascha Jenkins, 'Our Harbour: a cultural history of Sydney Harbour 1880–1938', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2004, p 213

[28] REN Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, London, 1883, p 20

[29] Mark Twain, Following the Equator: A Journey Round the World, American Publishing Co, Hartford, Connecticut, USA, 1897, p 113

[30] Peter McKenzie and Ann Stephen, 'La Perouse: an urban Aboriginal community', in Max Kelly (ed), Sydney City of Suburbs, New South Wales University Press in Association with the Sydney History Group, 1987, pp 177–179

[31] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005; Members of the Aboriginal community, La Perouse, the Place, the People and the Sea: A Collection of Writing, Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1988; Felicity Errington, 'Boomerang', in Melissa Harper & Richard White (eds), Symbols of Australia, University of New South Wales Press and National Museum of Australia, Sydney, 2009; Peter McKenzie and Ann Stephen, 'La Perouse: an urban Aboriginal community', in Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, New South Wales University Press in Association with the Sydney History Group, 1987, pp 173–191

[32] New South Wales National Park Trust, Official guide to the National Park of New South Wales, Government Printer, Sydney, 1902, pp 7–10; see also Wendy Goldstein, Australia's 100 years of National Parks, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney, 1979; Caroline Ford and Richard White (eds), A History of Recreation in New South Wales National Parks, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2012

[33] Peter Proudfoot, Roslyn Maguire and Robert Freestone (eds), Colonial City, Global City: Sydney's International Exhibition 1879, Crossing Press, Sydney, 2000, p x; Graeme Davison and Kimberley Webber (eds), Yesterday's Tomorrow: The Powerhouse Museum and its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 2005

[34] Clement Semmler, 'The Centennial's hope and despair. The Centennial celebrations of 1888', Bulletin, 26 January 1988, pp 137–139; Gavin Souter, Lion and Kangaroo: the Initiation of Australia, Collins, Sydney 1976; DB Waterson, 'Above and behind the arches: Aboriginals and the 1901 Federation celebrations', Federalist, no 6, December 2000, pp 40–48; Justine Greenwood, 'The 1908 visit of the Great White Fleet: displaying modern Sydney', History Australia, vol 5, no 3, 2008, pp 78.1–78.16; Julian Thomas, '1938: Past and present in an elaborate anniversary', in Susan Janson and Stuart Macintyre (eds), Making the Bicentenary, a special issue of Australian Historical Studies, vol 23, no 91, October 1988, pp 77–89; Peter Spearritt, 'Celebration of a Nation: the triumph of spectacle', in Susan Janson and Stuart Macintyre (eds), Making the Bicentenary, a special issue of Australian Historical Studies, vol 23, no 91, October 1988, 3–20; Gordon Waitt, 'The city as tourist spectacle: marketing Sydney for the 2000 Olympics', in David Holmes (ed), Virtual Globalization: Virtual Spaces/Tourist Spaces, Routledge, London and New York, 2001, pp 220–244

[35] Peter Spearritt, State of Play: 100 Years of Tourism in New South Wales, 1905–2005, Sydney, Tourism New South Wales, 2005; Sascha Jenkins, 'Our Harbour: a cultural history of Sydney Harbour 1880–1938', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2004

[36] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005

[37] Julia Horne, The Pursuit of Wonder: How Australia's Landscape was Explored, Nature Discovered and Tourism Unleashed, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2005, p 193; see for instance: 'The tourist: in and around Parramatta', Sydney Mail, 13 October 1888, p 68; 'The Orange Groves and Orchards around Parramatta', Australian Town and Country Journal, 28 January 1870

[38] Jeremy Steele, 'The Excursions Story', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 87, no 1, June 2001, pp 123–127

[39] Susan McClean, 'Negotiating the Nation: Audiences at Vaucluse House, 1915–1950s', unpublished paper, Australian Historical Association conference, Armidale 2007

[40] Justine Greenwood, 'Driving through history: the car, The Open Road, and the making of history tourism in Australia, 1920–40', Journal of Tourism History, vol 3 no 1, 2011

[41] Susan McClean 'Burdekin House: a turning point in preservation history', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, June 2007

[42] See also Richard White, 'The outsider's gaze and the representation of Australia', in Don Grant and Graham Seal (eds), Australia in the World: Perceptions and Possibilities, Black Swan Press, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, 1994, pp 22–28; Rebecca Mann, 'Thrills, Spills and Romance: Sydney's Luna Park in World War Two', History IV Honours thesis, University of Sydney, 2010

[43] Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, 'Migrants classified according to intended residence: Australia', Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, p 355; Tourism Australia, 'December 2010' , http://www.tourism.australia.com/en-au/5236_5263.aspx, viewed 18 April 2011; Tourism New South Wales, 'Travel to Sydney: Year Ended March 2006', p 2

[44] For instance, Sydney has been voted 'world's best city' for eight consecutive years since 2001 in the Condé Nast Traveller Readers' Choice Awards

[45] 'Rest and Recreation in Sydney – "R and R"', Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs, http://vietnam-war.commemoration.gov.au/all-the-way-with-lbj/rest-and-recreation.php, viewed 20 April 2011

[46] Lila Oldmeadow, 'Six Days to Live: American Servicemen in Australia on Rest and Recreation during the Vietnam War', History IV thesis, University of Sydney, 2003

[47] Paul Ashton, 'Place', Parallax 1: The Rocks, no 1, 1988; see also John Rickard and Peter Spearritt Packaging the Past: Public Histories, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1991

[48] Anna-Lisa Mak, 'Negotiating identity: ethnicity, tourism and Chinatown', Journal of Australian Studies, no 77, 2003, pp (93)–100,194–195

[49] Stephanie Hemelryk Donald and John G Gammack, Tourism and the Branded City: Film and Identity on the Pacific Rim, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2007, p 110

[50] Gordon Waitt and Pauline M McGuirk, 'Marking time: tourism and heritage representation at Millers Point, Sydney', Australian Geographer, vol 27, no 1, May 1996, pp 11–29

[51] Richard White with Sylvia Lawson, 'Sydney Opera House', in Melissa Harper & Richard White (eds), Symbols of Australia, University of New South Wales Press and National Museum of Australia, Sydney, 2009

[52] No Age – No More R&R, http://noagela.blogspot.com/2009_01_01_archive.html, viewed 7 April 2009

[53] Koala Park Sanctuary, 'The legend of Koala Park Sanctuary', http://www.koalaparksanctuary.com.au/myweb2/default.htm, viewed 19 April 2011

[54] Kevin Markwell and Nancy Cushing, Snake-Bitten: Eric Worrell and the Australian Reptile Park, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010

[55] John Connell, Sydney: The Emergence of a World City, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2000

[56] 'Sydney & beyond: Australia', Sydney: New South Wales Tourism Commission in co-operation with Austravel, 1992; Peter Murphy and Sophie Watson (eds), Surface City: Sydney at the Millennium, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1997, pp 40–44

[57] John Wilkinson, 'Tourism in New South Wales: prospects for the current decade', Briefing Paper no 8/06, New South Wales Parliamentary Library Research Service, 2006, pp 15–16, http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/PARLMENT/publications.nsf/0/A5480D46A9CE0129CA25717D00161D52/$File/Tourism%20in%20New South Wales&Index.pdf, viewed 20 April 2011

[58] Peter Spearritt, State of Play: 100 Years of Tourism in New South Wales, 1905–2005, Sydney, Tourism New South Wales, 2005, pp 8–9; 'Past Campaigns', Tourism New South Wales, http://corporate.tourism.nsw.gov.au/Past_Campaigns_p1560.aspx, viewed 20 April 2011

[59] 'Regional Tourism Profiles 2009/2010 – Sydney Region', Tourism Research Australia, January 2011, http://www.ret.gov.au/tourism/Documents/tra/Regional%20tourism%20profiles/2009-10/New South Wales_Sydney_acc.pdf, viewed 20 April 2011

[60] Bruno Gmünder, Spartacus: International Gay Guide, 1995

[61] Meaghan Morris, 'Metamorphoses at Sydney Tower', Australian Cultural History, no 10, 1991

[62] Urbanalyst, ‘Sydney’s new Darling Harbour precinct opens’, 4 October 2011, http://www.urbanalyst.com/in-the-news/new-south-wales/805-sydneys-new-darling-harbour-precinct-opens.html, viewed 21 November 2011

[63] Sascha Jenkins, 'Our Harbour: a cultural history of Sydney Harbour 1880–1938', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2004

[64] Germaine Greer, London Observer, 1 August 1982

.