The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Georges River: Flooding the City

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Georges River: Flooding the City

The earliest European settlement along the Georges was at places where the best of alluvial soils coincided with what we now know is the river flooding epicentre. In modern times, settlement has intensified – sparsely spread tiny cottages and ragged farming fields have been replaced by densely settled urban places. Today, more people are at risk of Georges River flood with communities relying on early flood warning systems, insurance, engineered control of floodwater and institutionally-provided rescue services. Climatic variability and flood events have always been an unpredictable feature of the river floodplain – this natural 'wild-card' could throw down even greater future challenges.

Aboriginal people, with thousands of years of experience, would have lived through severe natural catastrophes. There is a dreaming story of the Dharawal people, whose nation stretched from the southern bank of the Georges River and beyond, which describes the creation of the Gymea Lily following a huge storm that caused the death of a band of people. [1] There is evidence of tsunamis affecting the New South Wales east coast in the past 10,000 years. Such events have the capacity to run many kilometres inland, up the mouths of coastal rivers like the Georges. [2]

Why does the Georges River flood so badly?

[media]The Georges River is considered one of the most severely flood-prone rivers in NSW. [3] While many rivers flood in low coastal deltas, the Georges River actually floods worst away from its coastal mouth, in its middle reaches. As the river in flood rushes seaward, at around Picnic Point, the river banks rise steeply to form a narrow sandstone gorge which partially dams the water, worsening the situation upstream on the lower lying floodplain. The floodplain moves away from the river edged boundary of the suburban areas of Fairfield, Bankstown and Liverpool and advances deeply into them. These once discreet settlements have grown and spread and are now cities in their own right, coalescing to form part of the greater Sydney metropolitan area.

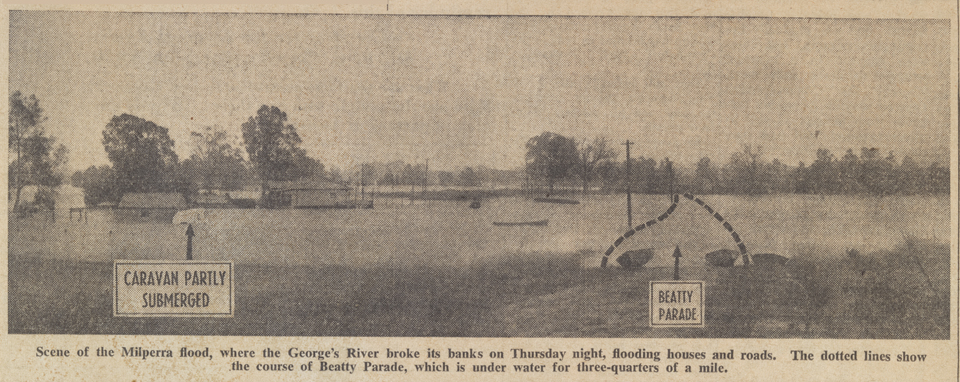

In these riverside city reaches, the river snakes around in circular meanders that slow the passage of river floods, allowing the swollen river to spill over its banks. One of the larger meanders is near Bankstown Airport and the river in flood takes a short-cut, a straight line cutting off the curve, with dangerously increased velocities, to form the Milperra Moorebank floodway.

'The biggest storm in living memory'

[media]In 1956 torrential rain caused the most damaging of floods known since the first European settlement of the Georges River floodplain, which began as early as 1798. [4] The flooding resulted from what was reported as 'the biggest storm in living memory'. [5]

Between Wednesday 8 February and the following Friday night, 300 mm of rain fell. As a result, Sydney-wide, there were 1,000 homes flooded and 8,000 people evacuated and temporarily homeless. To put this single storm event and subsequent flood impact into perspective, the mean annual rainfall of this area is 872.5mm. [6] Over two and a half days, this storm delivered more than a third of the average rainfall for a whole year. Many of the seriously flooded areas were around the Georges River in the suburbs of Bankstown, Panania, East Hills, Milperra, Moorebank, Chipping Norton, Georges Hall, Canley Vale and Lansvale. [7]

There were dramatic scenes and rescues. One resident at Hollywood Park near Lansvale, reported that the river rose 1.5 metres in just one hour. In the Milperra Moorebank floodway, 400 houses flooded, with houses along Henry Lawson Drive at East Hills almost completely submerged. Residents had to be rescued by police and army 'ducks' as well as by civilians in row boats. Many were 'plucked' from roof-tops and flooded verandahs and some were even found clinging to fence posts and trees or sitting on car tops. All of this is in the midst of Australia's largest city.

When residents returned to drenched homes after the water subsided, they found the heartbreak of ruined furniture, bedding and carpets, mud clogged and filthy. One family even reported a large eel in one room, and fish stranded and wriggling in another. [8]

Repeated floods followed, with resident evacuations and homes inundated in 1969, 1975, 1976, 1978 and 1986 and 1988. There has not been a serious flood since 1988 when more than 1,000 houses were inundated along the Georges River, Cabramatta and nearby Prospect Creek. While this flood was lower than that of 1956, damage to homes increased, reflecting growing urbanization, with more houses built since on low-lying land. [9]

Trends over time show that floods can cluster in a small number of years, not be experienced for decades, and reappear. For example, between 1901 and 1940 there were only two large floods on the Georges River, yet in the decade between 1969 and 1979 there were six.

Bigger floods forgotten

In 1873 the flood level at Liverpool was estimated to be two metres above the 1956 flood and three metres above those of 1986 and 1988. These floods were 'disastrous' with several houses totally washed away. [10] The 1873 flood was one of a cluster of floods that occurred between 1860 and 1899. An acute awareness followed and led to the erection of a sandstone marker on the river bank at Georges Hall that read: 'Flood was here May 24 to 29 1899'. [11] This early warning sign did nothing to prevent closer urban settlement of floodways, particularly after World War II.

A sobering comparison is that the more recent floods of 1986 and 1988 were only described to have been at the standard of 'one in 20 year' floods, when the flood of 1873 was a 'one in 100 year' event. [12] If even a one in 20 year event was to be repeated today, it would occur in a still more densely settled urbanised landscape, with greater human impact. The scale of damage from a one in 100 flood, like the 1873 event, could be catastrophic.

'Frequent inundations'

[media]An annotated map appeared in Watkin Tench's diary of 1793, showing his knowledge of the Georges River. In relation to its course, it disappeared just a little past its junction with a tributary on the north-side likely to be Salt Pan creek. He noted that the area between Prospect and Cabramatta was 'bad' country, 'frequently overflowed'. He was describing the floodplain heart of the present day city of Fairfield. Tench knew more of the Nepean-Hawkesbury and he noted on his map that floods there could reach a remarkable 50 feet (15.24 metres) above normal bank height. [13]

George Bass and Matthew Flinders advanced colonial knowledge a little in 1796 by sailing further up the Georges River to a place we now call Bankstown. Between 1798 and 1800, 3,247 acres (1.2 hectares) were granted along the Georges River in the locality of Garrison Point at the river confluence with Prospect Creek. This contained the richest of the alluvial floodplain soils but was also the absolute epicentre of the worst river flooding. It would offer both promise and unanticipated treachery for ill-prepared new settlers.

Documented flood levels on the Nepean Hawkesbury River from 1799 onwards demonstrate a maelstrom of repeated inundations that may well have been paralleled in the Georges River nearby. There was a particular cluster of extensively damaging floods – 11 in the 20 years between 1799 and 1819. [14]

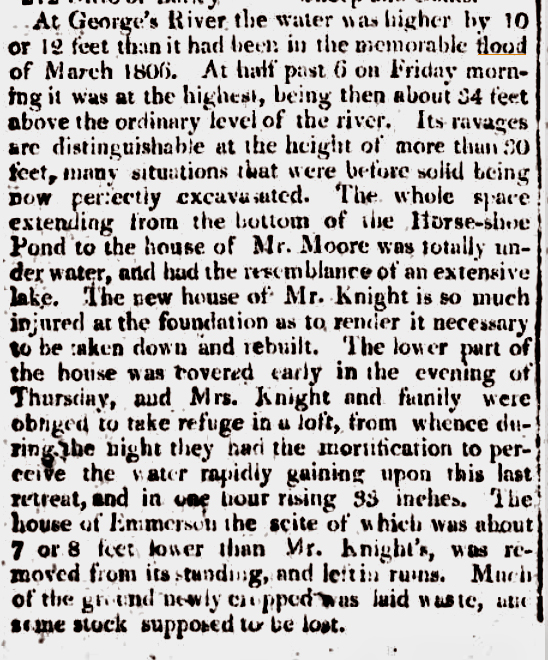

The flood hazard to early settlers and their crops along the Georges River and its tributaries has been acknowledged. [15] In December 1800, John Hopkins lost five acres (two hectares) of corn, eight acres (three hectares) of wheat, five pigs and almost a hundred fowl. His pregnant wife went into labour 'through the fright of the Water flowing into the house', and had to be 'got into the loft'. [media]The flood height at Liverpool in 1809 was 34 feet (10.3 metres). [16] A full appreciation of the fear, despair and utter isolation of people like the Hopkins, facing raging torrents and the ruined aftermath, has been largely lost with the passing of time.

Governor Macquarie visited the Georges River floodplain district in 1810 and his response to the 'frequent inundations' of the Nepean, Hawkesbury and Georges Rivers, which in 1806 had caused the 'most calamitous Effect with regard to the crops', was the opening up of higher land on the Cumberland Plain and a flurry of proclamations of townships on higher ground. [17]

Lessons learned

Government [media]and councils continue to take action from lessons learned after the floods of the late 1900s. [18] [19] Subsidies have been put in place for raising houses around Lansvale and a voluntary buy-back scheme of 200 high-risk properties in the Milperra Moorebank floodway was introduced in 1983. Yet despite town planning restrictions making new urban development on highly flood prone land more difficult, along Henry Lawson Drive – the scene of massive flood inundation in 1956 and flooding in 1986 and 1988 – small fibro shacks have been replaced by large expensive mansions.

Flood levees and gates, like those at Kelso Creek, have been built to hold and deflect water. Along tributary creek lines and drains upstream, councils have constructed parklands as retarding basins for excess surface flows, and now require storm water to be held on-site in new urban developments. These measures are planned to counteract the fact that rainwater rushes quickly towards rivers across hard surfaces. In highly urbanised catchments, swamps, grasslands and forests (which provide natural flood control by acting like sponges, soaking up and holding water and slowing its passage towards waterways) have been replaced by hard surfaces. In a trend towards water sensitive urban design, waterway managers now recommend soft surfaces be reintroduced into urban landscapes to achieve what nature used to do itself. Fairfield Council has recently funded projects to save and re-use water and prevent flooding. [20] These advances in engineered flood management, planning control and new urban design principles of the past few decades are yet to be tested by a huge flood event.

References

Bewsher Consulting, Georges River Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan, Georges River Floodplain Management Committee, May 2004

Tim Flannery (ed), Watkin Tenche's 1788, fourth edition, The Text Publishing Company, Melbourne, 2009

Christopher Keating, On the Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale and Iremonger, Marrickville, 1996

Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, second edition, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, 2010

Notes

[1] CW Peck, 'The First Gymea or Gigantic Lily: Campbelltown area' in Ellen Anderson and CW Peck, Australian Legends : Tales Handed Down from the Remotest Times by the Autocthonous Inhabitants of Our Land: Parts 1 and 2, Stafford, Sydney, 1925

[2] Emma Young, 'Tsunami: Terror from the Sea', Australian Geographic website, http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2010/12/tsunami-terror-from-the-sea/, viewed 27 December 2013;' Past tsunami events', Bureau of Meteorology website, http://www.bom.gov.au/tsunami/history/index.shtml, viewed 5 January 2014. Fortunately, of the over 50 recorded incidents of tsunamis that have hit the Australian coastline since European settlement, none have been serious enough to threaten either property of lives

[3] Georges River Combined Councils' Committee, 'Flooding', Georges River website, http://www.georgesriver.org.au/Flooding.html, viewed 5 January 2014

[4] Bankstown City Council, 'Settlement', Bankstown: City of Progress website, http://www.bankstown.nsw.gov.au/index.aspx?NID=362, viewed 5 January 2014

[5] 'The Floods', Sydney Morning Herald, 27 January 1873, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/13308463, viewed 8 January 2014; Bewsher Consulting, Georges River Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan, Georges River Floodplain Management Committee, May 2004, p 14

[6] Calculated on the basis of the 1969–2013 years, from Australian Government, 'Summary Statistics Bankstown Airport AWS', Bureau of Meteorology website, http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_066137.shtml, viewed 4 January 2014

[7] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, second edition, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, 2010, pp 107–8

[8] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, second edition, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, 2010, p 106

[9] Bewsher Consulting, 'Georges River Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan', Bewsher Consulting Pty Ltd, Epping, 2004, http://gis.wbmpl.com.au/ebooks/B18396/Georges%20River%20Floodplain%20Risk%20Management%20Study%20and%20Plan%20Vol1/files/assets/basic-html/page24.html, viewed 5 January 2014

[10] 'The Floods', Sydney Morning Herald, 27 January 1873, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/13308463, viewed 8 January 2014, in Bewsher Consulting, 'Georges River Floodplain Risk Management Study and Plan', Bewsher Consulting Pty Ltd, Epping, 2004, p 14

[11] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, second edition, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, 2010, pp 107

[12] Flood descriptions of a 'one in 20 year' or 'one in100 years' event are convenient but colloquial. The more accurate assessment of risk is that the former translates to a five per cent chance of a flood every year whereas the latter has a one per cent chance of happening every year

[13] Tim Flannery (ed), Watkin Tenche's 1788, fourth edition, The Text Publishing Company, Melbourne, 2009, p vi

[14] Michelle Nichols, Disastrous Decade: Flood and Fire in Windsor 1864–1874, Deerubbin Press, Berowra Heights, 2001, http://www.hawkesburyhistory.net.au/articles/floods.html, viewed 6 January 2014

[15] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, second edition, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, 2010, p 6; Christopher Keating, On the Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale and Iremonger, Marrickville, 1996, p 7; Stephen Gapps, Cabrogal to Fairfield City: A History of a Multicultural Community, Ligare, Riverwood, 2010, p 26

[16] Petitions to the Colonial Secretary, 1810–24, State Records NSW, 2/8130 in Christopher Keating, On the Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale and Iremonger, Marrickville, 1996, p 11

[17] Macquarie declared the township of Liverpool in 1810, noted in Christopher Keating, On the Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale and Iremonger, Marrickville, 1996, p 7

[18] John Maddocks, 'Have We Forgotten About Flooding on the Georges River?', Floodplain Management Authorities Conference, Wentworth Shire Council, 2001

[19] See Bankstown and Liverpool council proposals to National Disaster Mitigation Program under Australian Government, Approved Projects – Natural Disaster Mitigation Program, Attorney General's Department website, http://www.em.gov.au/Fundinginitiatives/Naturaldisastermitigationprogram/Pages/default.aspx, viewed 6 January 2014

[20] Fairfield City Council and Five Creeks Stormwater Management, 'Proposed Stormwater Works', Fairfield City Council website, http://www.fairfieldcity.nsw.gov.au/docs/Proposed_Stormwater_Works_2006_2007.pdf, viewed 5 January 2014

.