The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Religion

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Religion

The modern city of Sydney has a reputation to uphold for its larrikin spirit, hedonism and resistance to authority – including that represented by organised religion. Just how this reputation was achieved has never been seriously researched but it is usually assumed that Sydney's convict origins and the number of Irish Catholics in the demographic mix have something to do with it. In fact it is truer to say that religion has had a profound influence on the geography, culture, politics, and artistic life of the city. While religion in Sydney has mostly been a conservative force, preserving traditions transported there from home societies, it has also reflected the setting and people of Sydney, its harbour, bushland and suburbs. This article reviews the history of religion in Sydney and the role it has played in the lives of those who have made their home here.

Aboriginal traditions

The Aboriginal people of the Sydney region were divided socially and culturally into dozens of local clans and five main language groups: Guringai to the north, Darkinjung to the north-west of the Hawkesbury, Dharug on the coast (another Dharug dialect was spoken inland), Dharawal from the south side of Botany Bay down to the Shoalhaven, and Gundungurra on the southern rim of the Cumberland Plain and west to the Georges River. [1] From the observations of Watkin Tench and David Collins in the 1780s, as well as the accounts published by the ethnographer RH Mathews in the 1890s, it can be assumed that the religious beliefs of the Sydney people resembled those described in more detail by the missionary Lancelot Threlkeld for the people of Lake Macquarie (Awaba) and the Hunter River, whose language and country adjoined that of the Guringai to the north. Collins himself thought that Sydney's Aborigines were unique among the peoples of the world in having no religion of any kind, but in fact this is not the case.

Sydney's original inhabitants held totemic beliefs, or 'dreamings' as they are sometimes called in Aboriginal English, which established links between particular individuals and their clans and animals, plants or objects. They also believed that sorcery and magic were responsible for harmful events in their lives, including those for which a natural or human agent could be identified such as accidents, disease or failure in battle. But despite a sense of living in a malevolent universe, they maintained control over their environment and its hostile spirit forces through the expertise of the native doctor, who Collins calls the carahdis. With the aid of quartz crystals the carahdis was able to extract harmful elements from the body of afflicted individuals. According to Collins, Bennelong told him there was also considerable fear of the spirits of the dead who had the power to disembowel anyone sleeping close to a grave. Only the carrahdis could withstand their power. [2]

[media]Besides everyday sorcery, the Sydney people maintained a rich ceremonial life including male initiation rites held once every two or three years on specially constructed stages or bora grounds, which featured tooth evulsion and scarring. Collins describes a ceremony, which he calls Yoo-lahng erah-ba-diahng, that he observed at Farm Cove on the southern shore of Port Jackson in 1795. [3]

Aboriginal spiritual relics

Elements from this religious economy are reflected in hundreds of sandstone engravings (petroglyphs) which occur throughout the Sydney-Hawkesbury region. These depict a great range of creatures, including kangaroos and other small marsupials, emus, whales, sharks and large human figures. These can be found scattered all around Sydney harbour, sometimes buried under houses and gardens; some of the best surviving examples can be seen in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. Very little is known about their meaning. Even in 1847, George French Angas reported that old people refused to answer questions about them.

Human figures depicted at various sites in the Sydney region are sometimes identified as the ancestral beings known as Baiami and Daramulan among inland peoples such as the Wiradjuri, Yuin and Wongaibon. [4] However, there is no contemporary evidence for the recognition of superior beings among the Sydney people or the Awaba people further north described by Threlkeld (although Howitt makes a case for 'Koin'), [5] and scholars now argue that these beliefs reflect nativist responses to occupation and contact with Europeans. [6] Overall, the religions of Sydney's original inhabitants have reflected the flattened secular and sacred hierarchies of the traditional world. Religion also helped them negotiate the tensions of interactions with their neighbours across Sydney harbour and the Sydney basin as well as the wider world.

Colonial foundations

The British settlement of Sydney began with a reputation for immorality and rejection of religion which, to some extent, was well earned. [media]Although the First Fleet carried a chaplain, Richard Johnson, the government of the convict colony gave little priority to religious observance and none at all to that outside the established church. Two Catholic priests were with the French expedition which arrived not long after the First Fleet in 1788 and one has never left. The Franciscan naturalist, Laurent Receveur, died of wounds received in Samoa and was buried at La Perouse.

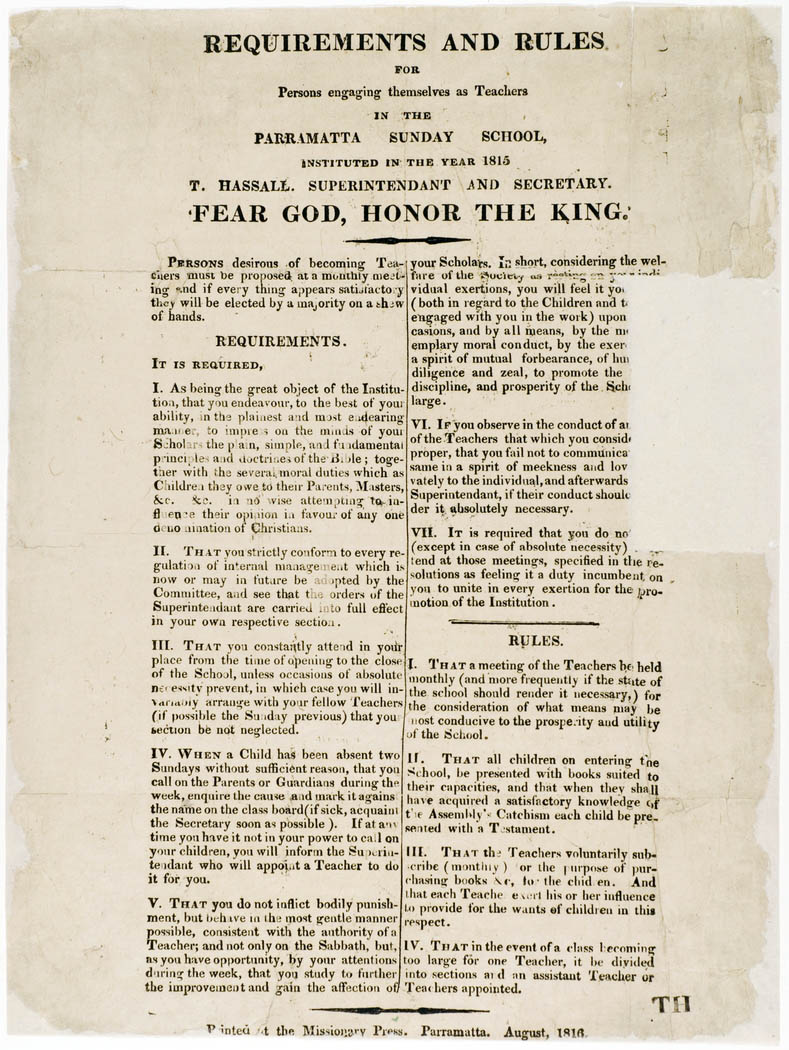

After five years without a church, Johnson was eventually driven to arrange for the erection of one at his own expense on the eastern side of Sydney Cove. Collins tells us that for his first sermon in the new building Johnson attempted to impress on the congregation the need for 'holiness in every place'. [7] This was easier said than done in a community burdened by anti-clericalism, habits of lawlessness, and ignorance of religion. But once the early anxieties of settlement were past, religion was encouraged by a succession of colonial administrators in the ambitious hope that it would encourage [media]morality and respect for authority.

Governor Macquarie used his patronage to erect handsome churches which reflected the values of the ordered civil society with the established church at its core that he hoped to emerge from the Sydney soil. As acting civil architect in New South Wales, the emancipist artist Francis Greenway was responsible for many of the best-loved of these such as St Matthew's church, Windsor (foundation stone 1817), St Luke's church, Liverpool (foundation stone 1818, completed 1824), and St Matthew's Rectory, Windsor (completed 1825) as well as others now demolished. [8]

There were signs that the ministrations of the colonial chaplains were regarded with less affection by the convicts. [9] [media]Johnson's church was destroyed by arson and, in a much repeated story, when Governor Macquarie laid the foundation stone for St Matthew's church at Windsor on 11 October 1816, the ceremony had to be repeated when it was discovered that the silver dollar that Macquarie had placed under the stone had been stolen. [10] Yet even from the surviving evidence of the churches of central Sydney and the townships established along the Parramatta and Hawkesbury Rivers, it is evident that religion played a central role in the civic organisation of early Sydney.

A feel for the place of religion in the early colony can be obtained at the site once known as Church Hill, near where the Sydney Harbour Bridge now disgorges traffic into York Street. Although none of its original churches are now visible, three major Christian traditions are represented on this elevation. [media]On the western side of York Street is St Philip's Anglican church, built on the site of the oldest parish church and one of the earliest schools in the city. On the slope of Grosvenor Street, off York Street, is St Patrick's Catholic church where a chapel was dedicated in 1844 (though the first Catholic chapel was built earlier under what is now St Mary's cathedral). On the eastern side of York Street is a memorial to John Dunmore Lang's Scots church, erected in 1824 shortly after Lang's arrival in Sydney.

Presbyterian and Unitarian worship can be said to have begun with the psalms and prayers offered by the 'Scottish martyrs' transported for sedition in 1793. [11] Lang's ardent support of the cause of the poor Scottish emigrant, and his agitation against the establishment in church and state and the Catholic religion, exacerbated divisions in the Presbyterian church. [media]These divisions are reflected in the complicated history of St Stephen's Uniting church (dedicated 1835), now enjoying a prime site in Macquarie Street facing State Parliament House, but originating in secession from Dr Lang's Scots church on Church Hill.

Counting the faithful

It is significant that at the time of the first census of New South Wales, in November 1828, it was assumed that everyone in the colony could be counted as belonging to one of four religious groups: Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, and Pagan. Jews and 'Pagans' lived mostly in Sydney Town, the Camden district was rather more Catholic (39 per cent) and the Windsor district was rather more Protestant (79 per cent) than elsewhere, but the colony was not religiously divided, at least geographically, though sectarianism has played a role in the life of the city.

Church and state in the colony

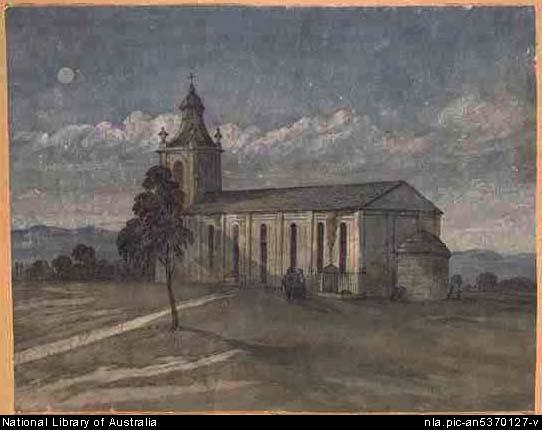

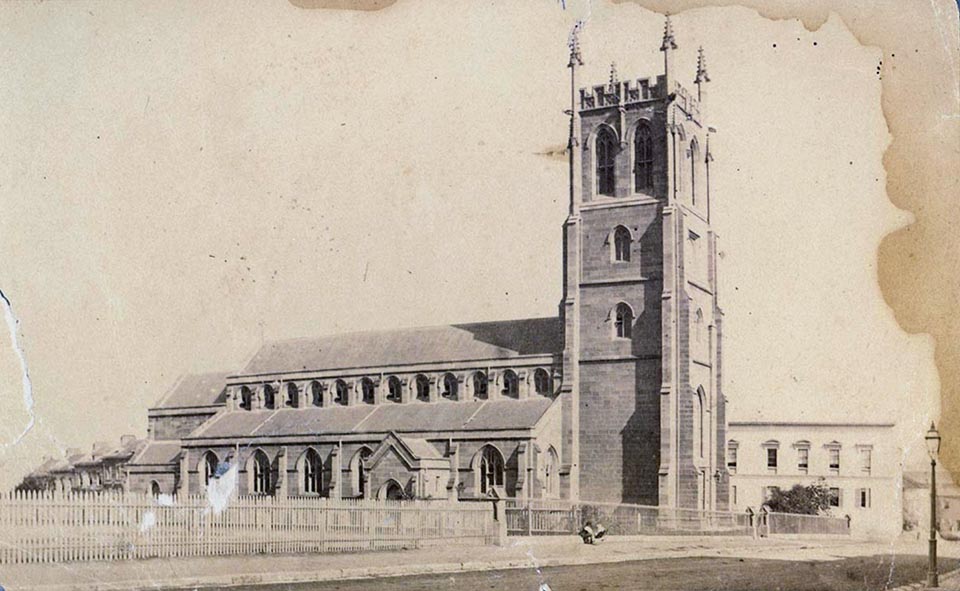

Commissioner Bigge refused to allow Governor Macquarie to proceed with the plans drawn up by Greenway for a grand metropolitan church in the gothic style that Greenway claimed would 'prove a credit to the Mother Country and exalt the respectability of the Colonists'. [12] [media]Macquarie, himself a Scottish Episcopalian, had laid the foundation stone of St Andrew's church in 1819 but the Anglican cathedral was not completed until 1868. St James's church on King Street was consecrated in 1824 in a building originally intended as a courthouse and it soon attracted the patronage of Sydney's fashionable classes.

The failure of Macquarie to build a great cathedral at the heart of Sydney set – as Greenway had imagined – like a new St Paul's in London, in a noble city square, reflected the direction religion was to take in the new settlement. The proposed square was eventually occupied by Sydney's Town Hall and Queen Victoria Building; the limits set on the established church created opportunities for other religious traditions and the religious toleration which was an early feature of Sydney life.

In 1836 Governor Richard Bourke secured the passage of a Church Act , 'to promote the building of churches and chapels, and to provide for the maintenance of Ministers of Religion in New South Wales'. The act does not specify which religious bodies were to be eligible for grants, although the requirement that that congregations had to raise at least £300 to receive a building subsidy placed practical limits on what might be done. The Church of England continued to receive the bulk of funding, reflecting its majority position in the colony, with lesser amounts going to the Presbyterians, Catholics and Methodists. [media]Imposing city churches emerged on sites around Hyde Park and down Macquarie Street. York Street was the location for the Methodist chapel which came to be known as 'the cathedral of Methodism' [13] and a Jewish synagogue. The most conspicuous losers from the Church Act, 1836 were those denominations that refused to accept government subsidies, such as the independent Presbyterians led by JD Lang, and the Congregationalists. In the wake of a series of sectarian disputes about government support for church schools, all state aid for religion was withdrawn in 1862.

Denominational traditions

Two of the most distinctive features of Sydney's religious character emerged in the colonial period, namely the strength of the evangelical party in what was to become the large and wealthy Anglican diocese of Sydney, and the relative importance of Catholicism and of Irish Catholicism in particular. [14]

Anglicans

[media]Evangelicalism has dominated the Anglican diocese of Sydney since the episcopacy of Frederic Barker, the second Anglican bishop of Sydney, who adapted particularly well to the new voluntarist regime which followed the removal of state aid to religion. [15] Evangelicalism was also cemented through the role played by Moore Theological College, founded by Barker in 1856, graduates of which eventually predominated in Sydney (though not before the end of World War I). From the 1930s, and especially since the 1980s, a more assertive and uncompromising expression of evangelicalism has become influential in the diocese of Sydney. It stresses the importance of doctrinal correctness, opposes what it sees as theological liberalism and seeks to reform the Anglican Church still further in a Protestant and evangelical direction. The minority Anglo-Catholic tradition, especially its fine music, is expressed in the worship of St James's church, King Street, and at Christ Church St Laurence, near Railway Square.

Catholics

[media]Fear of Catholic influence in the city has been a perennial feature of Sydney sectarian politics since the anti-Catholic polemic of John Dunmore Lang began in the 1820s. While the number of Sydney Catholics recorded in census returns has always been relatively high compared with other Australian cities (falling to a low of 21.1 per cent in 1933 but rising to 30 per cent in the 2006 census), it is difficult to judge the extent to which these numbers were translated electorally. While Catholics were highly successful in both local and state government, most politicians were at pains to distance themselves from their religious roots in order to avoid electoral backlash. Catholic influence was probably strongest in the inner city, but this was also where discrimination in employment and other forms of sectarian prejudice were most overt. Robin Eakin notes that in the 1930s wealthy Protestant and Jewish families like hers in the eastern suburbs looked down on Roman Catholics: 'They were common, and Irish, and politically Left – and that was that'. [16]

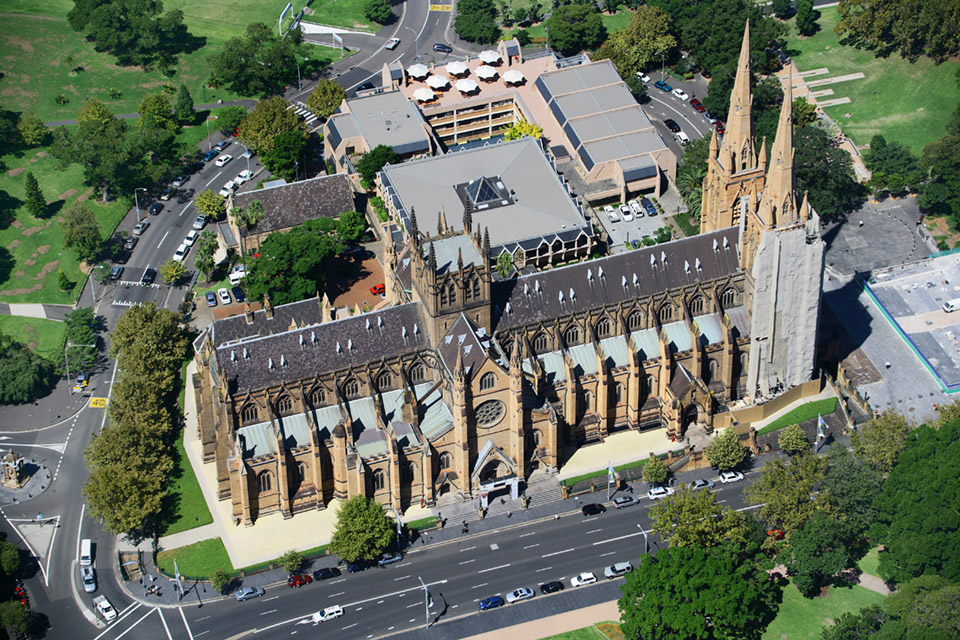

[media]The general sense that Catholics at least aspired to an influence out of proportion to their rights is reflected most magnificently in St Mary's Cathedral, designed in Gothic Revival style by William Wardell and built on the site of the first St Mary's which was destroyed by fire in 1865. This is a monument not just to the Catholic heritage in Sydney but also to the Sydney sandstone with which it is constructed. It is the largest cathedral in Australia and the biggest Christian church erected anywhere in the former British Empire outside Britain; 'This is huge,' tuts Jan Morris. [17] It looks particularly fine in aerial photographs where its bulk is dissipated by the surrounding parkland and the harbour beyond, and it is possible to admire the spires which were finally completed in 2000 with generous government funding.

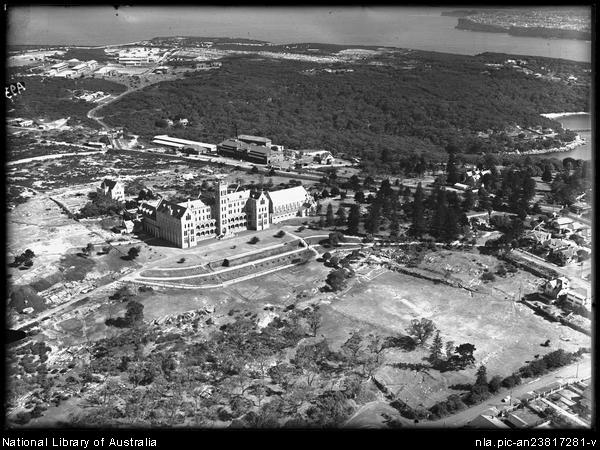

[media]The imperial ambitions of Sydney's third Catholic archbishop, Patrick Francis Moran, are reflected in St Patrick's College (1889), another massive statement in Gothic sandstone, which he built to command the headland at Manly. It is now the International College of Management.

Dissenters and others

Of the smaller Protestant denominations, Congregationalism and Methodism had a presence from Sydney's earliest days, and they were also among the first to send out missionaries to both the Aborigines and, through the London Missionary Society, to the Pacific islands. The first Baptist service was held at Woolloomooloo Bay in 1832, [18] and the Salvation Army began work in New South Wales in 1882. By the time the Methodists were united nationally, which occurred in 1900, they were the third largest denomination in Australia. However, non-conformist Protestantism has tended to be weaker in Sydney than elsewhere – probably because of the strength of Sydney's Anglican and Catholic mainstream, as Jill Roe suggests. [19] [media]Congregationalism has been visible, despite small numbers of adherents, partly because of its central church, now Pitt Street Uniting church (foundation laid 1841), and also because of its energy in establishing Sunday schools.

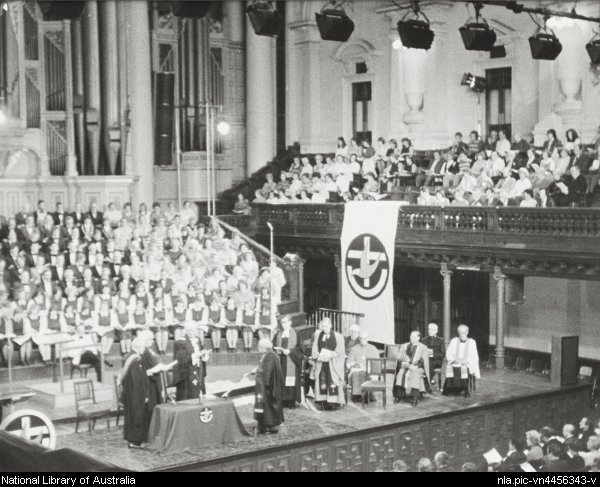

[media]When the Uniting Church of Australia was inaugurated at a service in Sydney Town Hall on 22 June 1977, it brought together the majority of Congregationalists, Methodists and, in New South Wales, just over half the Presbyterians, reflecting the shared theology and history of these denominations in Australia. The Uniting Church's relatively liberal theology and the mostly English roots of its antecedent churches, which have not been renewed by recent emigration, have contributed to decline in recent decades. This can partly be attributed to the impact of union, but also reflects the functions that churches have had in Australia where tradition rather than innovation has always been valued highly. Pitt Street Uniting church now promotes an inclusive ministry regardless of race, gender or sexual preference. It has moved substantially from the attitudes of Sydney's mercantile elite, including David Jones and the Fairfax family, who were once prominent in its congregation.

Methodism's most significant contribution to the life of Sydney has been through its welfare programs, a reflection of the 'social gospel' which sought to find Christian solutions to social problems, particularly those which afflicted the urban poor. The movement was fundamental for the Salvation Army. [media]In 1886 the Wesleyan Methodists made a radical decision to demolish the old York Street Chapel in order to establish a base for missions to seamen, inebriates and homeless children, and a training institute for evangelists. [20] In 1906 the Central Methodist Mission moved to the Lyceum Theatre in Pitt Street, later redeveloped into the Wesley Mission. While remaining one of the most socially active of Sydney's churches, in the 1950s Methodists were divided when the Reverend Alan Walker launched the 'Mission to the Nation', which had a strong social justice message, feeling that it was more important to fight what were perceived to be declining moral standards. Walker founded Lifeline in 1963 which aimed to use the telephone to offer counselling to people in need.

Theology and controversy

Religion has not been a notably creative force in Sydney's cultural life and the city is conspicuously lacking in prophets or founders of new religions. On the other hand, migrants have been solicitous in bringing their religious differences with them, and disputes in Britain, such as the division between different varieties of Presbyterianism, or Methodism, have quickly been translated into divergent ministries in Sydney – as elsewhere in Australia.

Theological controversies of more than passing seriousness have been an occasional problem for all churches. [21] Presbyterians have divided over the nature of the relationship between church and state and the reception of 'higher criticism'. In 1933, Samuel Angus, professor at St Andrew's Theological Hall, University of Sydney, was charged with heresy. [22] In 1993, Peter Cameron, also of St Andrew's, met the same fate. Anglicans have been more troubled in recent years over the issue of women's ordination, while the Uniting Church of Australia remains divided over the ministry of gay and lesbian clergy.

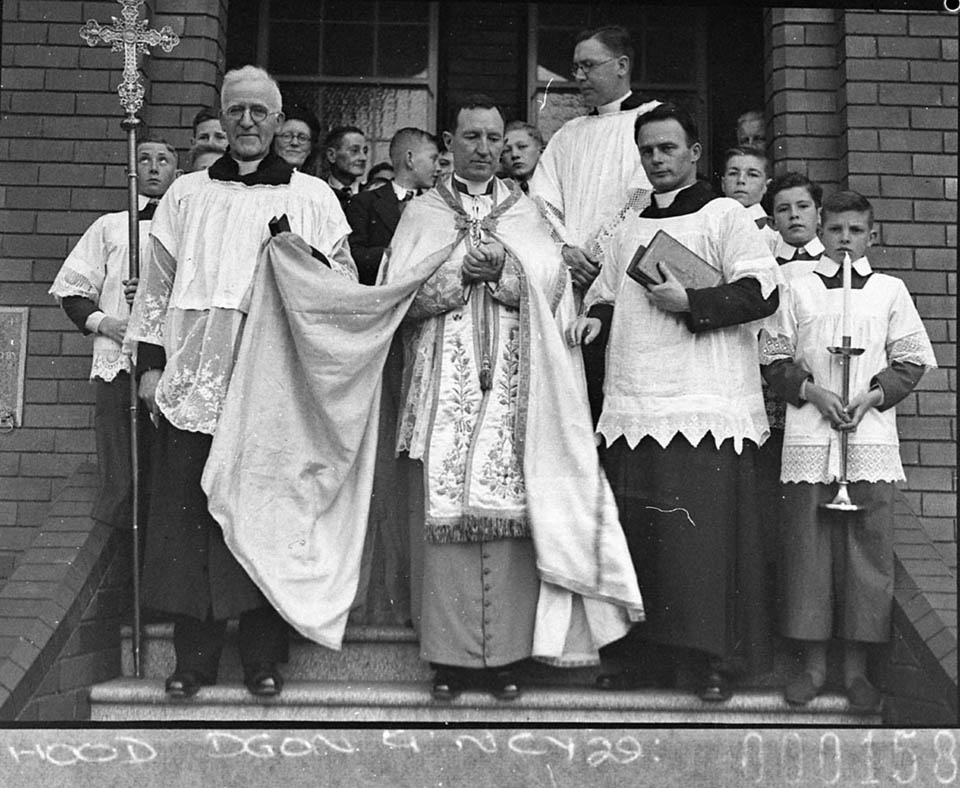

The Catholic Church has been shielded from such divisions by the authority and ultramontane habits of its higher clergy. [23] Sectarian politics in New South Wales probably reached its peak in the 1920s when Catholics made up 61 per cent of Labor parliamentary party members. [24] [media]Although the first two Archbishops of Sydney were English Benedictines, Irishmen held the see of Sydney until the succession of Norman Gilroy in 1940. The clerical ascendancy was challenged from Melbourne by the anti-communist layman, BA Santamaria, whose activities were instrumental in the split in the Australian Labor Party (1954–1957). While many Melbourne Catholics abandoned their traditional allegiance to the Labor Party to join Santamaria's Democratic Labor Party, in Sydney the Catholic hierarchy supported a continued alliance with the Labor Party and Catholics tended to remain loyal to the right-wing faction.

Theosophy and others

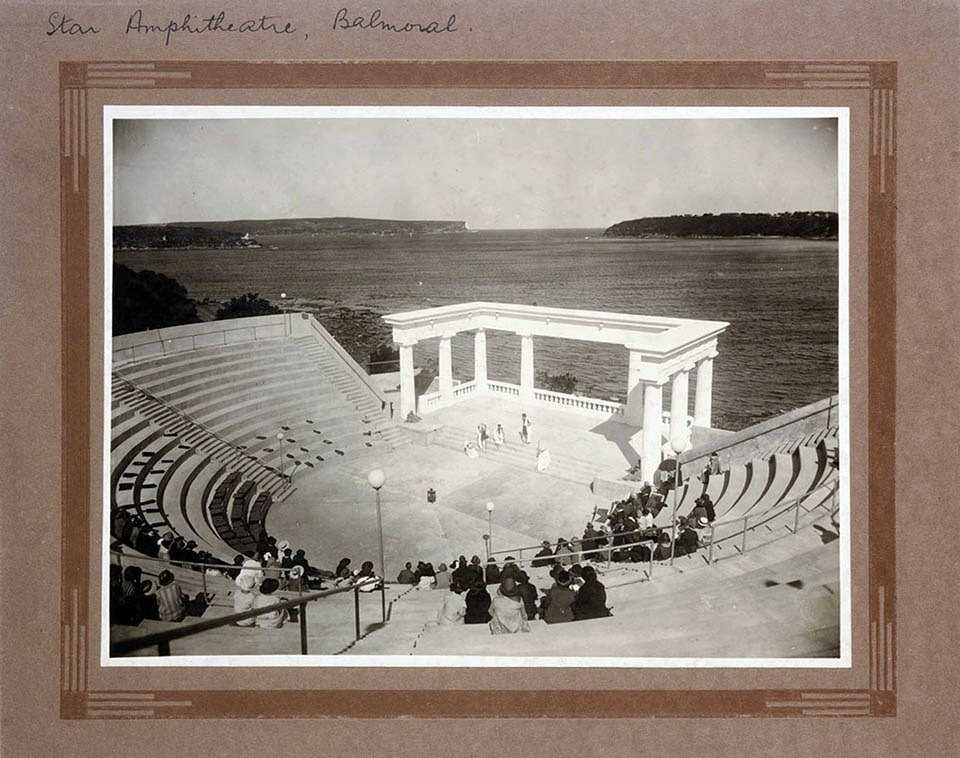

For those unhappy with majority Christianity or Judaism, there were alternatives available in the fin de siècle Sydney scene. Utopianism, both religious and secular, Unitarianism, Spiritualism, Theosophy, Anthroposophy and Christian Science all found adherents. [25] Artists, writers, and intellectuals were attracted to some of these. Professor John Smith of the University of Sydney was an early adherent of Theosophy, as was the remarkable Charles Leadbeater who followed a trajectory from Anglo-Catholicism to Theosophy. Leadbeater gathered a group of strong-minded and relatively prosperous people round him in the theosophical commune known as 'The Manor'.[media] The most visible symbol of this movement was the amphitheatre for 'The Order of the Star in the East' at Edwards Beach, Balmoral, which opened in 1924. [26] This had the spiritual purpose of receiving the one known to Theosophists as the 'World Teacher' but it was also a commercial venue where spiritual and cultural events might fuse in a dramatic seaside setting.

Wowserism and anti-clericalism

Despite such exercises in social and political activism, Sydney's churches have tended to attract criticism for failing to meet the needs of Sydney people. One legacy of the convict origins of Sydney was a sensitivity to the moral standing of the community. Moral reform was interpreted narrowly by the Protestant churches to concern sex, alcohol and gambling and was extended only secondarily to social issues. There was overwhelming support from all the churches for an end to transportation and this was followed by advocacy of moral reforms including temperance and Sabbatarianism, or strict observance of a restriction on work and leisure activities on Sunday. [27]

Following the formation of the Temperance Society in 1834, public bathing was restricted to more secluded stretches of Sydney harbour and there was general support for a restriction on Sunday trading. Sabbatarianism was supported not only by most churches but by trade unionists who believed that workers were entitled to Sunday enjoyments free from work obligations. These restrictions on Sunday trading by hotels were not removed entirely until 1979, though the restraint on Sunday activities was less onerous in Sydney than in other capital cities. This may be testimony to the superior competing attractions of Sydney's climate and ethos.

Anti-clericalism was one component of the radical nationalism associated most intimately with the Bulletin in the 1890s. [media]Popular anti-clericalism is reflected in the work of Sydney writers of this period, notably Henry Lawson. However affirmation of religious piety is no less evident as, for example, in Ethel Turner's popular children's novel Seven Little Australians (1894), set largely in Parramatta, in which the tragic death of Judy is mitigated by the words of hymns recited to her by her sister. Satire on religious conformity was expressed in more ebullient terms by the small group of bohemian artists and writers of whom Norman Lindsay was the most internationally successful. His Crucified Venus, exhibited in September 1913, expressed in unequivocal terms his view that traditional Christianity was responsible for the suppression of much that was joyous in human nature. In the twentieth century, secularist opponents of religion have included the philosopher John Anderson and his followers, and the journalist Phillip Adams.

Churches and education

Although there was no state aid for religion in New South Wales after 1863, this did not mean that the churches ceased to play a role in city life and they remained prominent in the provision of private education, hospitals and social welfare. Most Catholics of all classes received their primary and secondary education in Catholic schools which were staffed by teachers drawn from religious orders, but Protestant secondary schools were largely the preserve of the professional elite. [28] By 1950, only 4 per cent of New South Wales school children attended Protestant, non-denominational and 'other religion' schools and 20 per cent attended Catholic schools, with all the rest catered for by the government sector. [media]Church schools for this privileged group were concentrated along the train lines which ran from Stanmore to Strathfield in the west and from Kirribilli to Hornsby on the north shore, or in the salubrious harbourside eastern suburbs.

But with its early commitment to secular education, Sydney was distinctive in the extent to which members of the professional elite were educated outside the church sector in selective government high schools. The ideal of a high quality, secular, government-supported education was also reflected in the establishment of the University of Sydney. Despite vigorous campaigning by John Dunmore Lang and others, the role of the churches was restricted to their residential colleges.

Churches and health care

Health care was another field in which the churches provided services. The first trained nurses to come to Sydney were the Sisters of Charity who established St Vincent's Hospital at Potts Point. Catholic hospitals at Lewisham and North Sydney were run by the Little Company of Mary and the Sisters of Mercy respectively, though as the twentieth century progressed this was only possible with increasing financial support from the state government. In 1982, the Mater Hospital at North Sydney became the first public hospital in New South Wales to be closed following the withdrawal of funding by the state government. Since this time, the churches have moved decisively into private health and aged-care provision and out of the public sector.

Suburbanisation

[media]In the 1920s Sydney's Irish Catholics favoured the inner-city working class suburbs of Redfern, Surry Hills, Darlington, Waterloo, Glebe and Paddington. It was this Irish-Catholic community that is depicted in Ruth Park's novels, The Harp in the South (1948) and Poor Man 's Orange (1949). 'This is where we belong', says one character when there is talk of slum clearances and movement out of Surry Hills. [29] North of the harbour, Sydney's wealthy suburbs were said to become progressively more Protestant.

In the decades after World War I, Sydney's expanding outer suburbs were colonised by the churches for schools, theological colleges and hospitals. As the inner city lost its churchgoing population, the major Christian denominations built new churches in the suburbs stretching along the railway lines and bus routes. The denominations with the largest congregations, such as the Anglicans and Catholics, were better able to secure prominent sites on hills and close to public transport. The continued development of this religious infrastructure is one indication that, until the 1960s, religion continued to play a significant role in the community and self-perception of many suburban Sydneysiders, although within an overall context of secularisation.

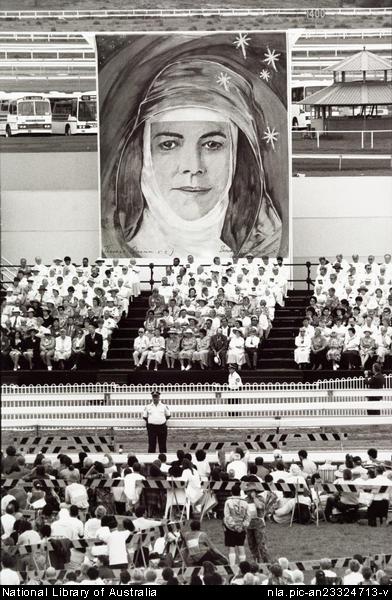

[media]Yet the city and [media]suburbs were always closely connected. From the 1950s, the arrival of the car ensured that churchgoers could be more mobile and, despite the strictures of priests and ministers, it became easier to seek out more lively preachers and more convivial congregations. The car also made it possible for the major city churches to draw attendances back for city festivals such as state funerals, midnight mass on Christmas Eve in St Mary's cathedral or quasi-religious events such as Carols by Candlelight. The largest of all religious rallies spilled out even from the vast expanse of St Mary's onto the Sydney Domain, Randwick racecourse or the Sydney Showground.[media] These were the settings for the biggest religious gatherings in the city's history, including the great rallies of Billy Graham in 1959 and 1968, and the papal visits by Paul VI (1970) and John Paul II (1986 and 1995) who celebrated a mass of beatification for Mary MacKillop at Randwick racecourse in January 1995.

The smaller Christian churches did better in the upper north shore and Hills districts, sometimes called 'Sydney's bible belt'. In Wahroonga, now on busy Fox Valley Road but then in a virtual wilderness, the Seventh-day Adventists built a sanatorium in 1903 for the training of medical missionaries. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) had been in Sydney as early as 1851 but the majority of converts emigrated to Utah in the United States. In the 1960s they began to re-emerge as a feature of suburban life through the house-to-house visits of neatly dressed young American missionaries offering the Book of Mormon. In 1984, a spectacular Mormon temple at Carlingford was eventually crowned – after a delay caused by building restrictions – with a towering golden statue of the Angel Moroni. These northern reaches of the city have also been a favourable environment for the Pentecostal churches, such as the Assemblies of God, which are now a familiar part of the suburban landscape.

Religion and migration

As a city of first choice for many new arrivals, Sydney has always reflected the cultural and ethnic origins of successive generations of migrants but that has predominantly meant different kinds of Christianity. British Jews were among the first settlers, both convict and free, and demonstrated their loyalty and imperial patriotism by high levels of enlistment in World War I and in plaques to the war dead as displayed in the Great Synagogue. Jews were also active as Freemasons. [30]

The Chinese were the first non-Europeans to make an impact on Sydney's religious landscape. Chinese immigrants contributed to the building of joss houses, of which the most important surviving example is the Sze Yup temple in Glebe. [media]But many Chinese also adopted Christianity, either through the teaching of Chinese evangelists or through the agency of the Chinese missions conducted in city areas by the Methodists and the (Anglican) Church Missionary Society. In time, many Chinese were also attracted to the Chinese Presbyterian churches established by the Reverend John Young Wai who came to Sydney in 1882. [31] The Chinese generally faced relentless discrimination in Sydney from which the churches did little to protect them.

World War II was a watershed in Sydney's religious history, as for the rest of Australia. Postwar migration affected the old Christian churches as well as reinforcing non-Christian religions and accentuating some religious differences between Sydney and other Australian cities. The Irish ascendancy in the Catholic church was challenged by thousands of migrants from predominantly Catholic countries such as Italy, Malta and Poland, as well as Maronites from Lebanon. More recently Catholics from Vietnam, the Philippines and Pacific Islands have become important. Orthodox Christians from Greece, Russia and Eastern Europe have had less of an impact in terms of sheer numbers in Sydney than in Melbourne. However an Orthodox Theological College, St Andrew's, is located in Sydney's inner-city suburb of Redfern.

Sydney's Jewry has remained smaller than that of Melbourne and also somewhat more cosmopolitan, partly because Melbourne attracted a much higher proportion of Polish Jews in postwar migration. [32] In more recent years, South African Jews have added dynamism to Sydney's Jewish community and have tended to settle close to the Jewish day school in St Ives. Jews in Sydney can still be found in larger numbers in Sydney's eastern suburbs, especially the local government areas of Waverley, Woollahra, and Randwick, but new arrivals have also moved north into the more affluent suburbs of Ku-ring-gai.

Of [media]the other major world religions, it has only been in the last 20 years that migrants from Asia and the Middle East have established significant communities of Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims in Sydney. Some of these have fled religious persecution, such as the Christian Assyrians, or Iranian Baha'i. [media]The Baha'i House of Worship (dedicated 1961), set in rural bushland in Mona Vale, preaches a doctrine of peaceful coexistence. This resonates well with the needs of new religious communities who seek to establish a presence in the bustling multicultural city that Sydney became as barriers to immigration fell in the 1970s.

Migrant churches emerged beyond the old city core, which had been the heartland of British settlement, and staked out new domains in the west. [33] In Sydney, local government areas with high numbers of Muslims include Canterbury, Bankstown, Auburn, Rockdale and Parramatta, all in the western suburbs. In a major show of confidence, the Gallipoli Mosque, the largest in Australia, was built in the 1980s at Auburn by Turkish Muslims. Lebanese Muslims mostly worship at the Lakemba Mosque, where the former Mufti of Australia and New Zealand, Taj El-Din Hilaly, generated controversy through his perceived support for Islamist causes.

Greater visibility in worship came at a time of increasing media focus on Muslims as a religious rather than an 'ethnic' or migrant category, something unusual in Sydney's history. [34] Together with national and international tensions, a series of crimes in Sydney beginning in 1998 led to a moral panic that the Arabic Muslim community harboured gang rapists who were targeting 'Caucasian' women. Religion was also a factor in the predominantly ethnic tensions leading to the violent confrontations on Cronulla and other Sydney beaches on 11 December 2005, the so-called 'Cronulla riots'. In contrast with the mainly inner-west and working-class settlement pattern of Muslims in Sydney, Hindus and Sikhs, who have also chosen to settle in Sydney in preference to other parts of Australia, have congregated in the middle-class enclaves of Blacktown, Canterbury, Vaucluse and Ryde.

Religion today

Judging by the statistics recorded on census returns, religion in Sydney within the mainstream Christian denominations has suffered a decline, but non-Christian traditions and Pentecostalism have increased in the 10 years to 2006.

Religion in Sydney – census years 1996, 2001, and 2006

| 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | ||

| Buddhism | 75,977 | 135,689 | 153,407 | |

| Christianity: | ||||

| Anglican | 825,237 | 797,706 | 738,387 | |

| Assyrian Apostolic | 5,508 | 6,221 | 6,990 | |

| Baptist | 61,665 | 61,418 | 61,114 | |

| Brethren | 4,209 | 3,740 | 4,193 | |

| Catholic | 1,140,958 | 1,185,095 | 1,197,652 | |

| Churches of Christ | 8,106 | 6,733 | 5,989 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 162,982 | 174,079 | 178,610 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 12,613 | 12,506 | 12,052 | |

| Latter Day Saints | 10,171 | 12,024 | 12,018 | |

| Lutheran | 20,610 | 19,220 | 18,532 | |

| Oriental Orthodox | 16,485 | 18,479 | 20,147 | |

| Other Protestant | 11,056 | 11,238 | 13,191 | |

| Pentecostal | 26,927 | 36,345 | 46,006 | |

| Presbyterian & Reformed | 123,540 | 117,327 | 107,576 | |

| Salvation Army | 9,891 | 9,416 | 8,221 | |

| Seventh-day Adventist | 10,587 | 10,880 | 10,635 | |

| Uniting Church | 168,443 | 155,837 | 138,007 | |

| Christian nfd | 31,671 | 43,935 | 52,074 | |

| Other Christian | 5,963 | 6,025 | 6,486 | |

| Total Christian | 2,656,622 | 2,688,224 | 2,637,880 | |

| Hinduism | 32,747 | 48,450 | 70,164 | |

| Islam | 96,617 | 134,028 | 161,164 | |

| Judaism | 31,733 | 33,331 | 35,253 | |

| Other religions: | ||||

| Australian Aboriginal traditional religions | 175 | 177 | 213 | |

| Other religious groups | 15,368 | 21,916 | 27,396 | |

| Total other religions | 15,543 | 22,093 | 27,609 | |

| No religion | 504,250 | 470,263 | 582,387 | |

| Other religious affiliation | 11,943 | 62,380 | 23,052 | |

| Religious affiliation not stated | 291,985 | 355,531 | 428,274 | |

| Total | 3,717,417 | 3,949,989 | 4,119,190 |

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics)

As the city has become more diverse, new religious options, including post-Christian practices such as Wicca, have found space to flourish. Since the 1970s many churches have established active Aboriginal ministries, including Father Ted Kennedy's Catholic church in Redfern. While 71 per cent of Sydney people still registered as Christians in 1996, by 2006 this had fallen to 64 per cent. Levels of active participation, always difficult to measure but captured to some extent in church and Sunday school attendances and in opinion polls, are only a small proportion of these figures. Those who prefer to omit the religion question or state that they have no religion have risen from 22 per cent to 25 per cent of the population, and even the mighty Catholic Church, Sydney's largest and most international denomination has declined from 31 per cent to 29 per cent of the total over the last ten years.

In the same period, all the major non-Christian religions, including Judaism, have shown an increase with Islam rising from 2.6 per cent to just under 3.9 per cent to nudge out Buddhism (3.7 per cent) as the largest non-Christian religion in the Sydney population.

Of the Christian churches, only the Pentecostals have shown an increase, from 0.7 per cent to 1.1 per cent in the same period. The current strength of Pentecostalism is reflected in the growth of the Hillsong church (formerly Hills Christian Life Centre) based in Baulkham Hills, where it grew out of a branch of the previously unremarkable Assemblies of God. The Hillsong website claims that it has now become the largest individual church in Australian history with its Sunday services drawing over 20,000 people each week. Unsurprisingly, it has attracted interest from politicians keen to understand both its impact and the sources of its success. [35] It certainly makes a contrast to the first services of Reverend Richard Johnson and his battles to erect a church in Sydney Cove. Whether it will succeed in sustaining its growth in the face of Sydney's relaxed relationship with the many religions which have struggled to make their mark in this city remains to be seen.

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2002

Ian Breward, A History of the Australian Churches, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993

Ian Breward, A History of the Churches in Australasia, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

James Broadbent and Joy Hughes, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 1997

Robin Eakin, Aunts up the Cross, Anthony Blond, London, 1965

Susan Emilsen, A Whiff of Heresy, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1990

Brian H Fletcher (ed), An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol 1 by David Collins, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1975, first published 1798

AM Grocott, Convicts, Clergymen and Churches, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1980

Niel Gunson (ed), Australian Reminiscences and Papers of LE Threlkeld, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1974

Gerard Henderson, 'The Catholic Church and the Labor Split', in Jim Davidson (ed), The Sydney–Melbourne Book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986, pp 218–28

LR Hiatt, Arguments about Aborigines, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996

M Hogan, 'The Sydney Style', in Labor History, no 36, 1979, pp 39–45

M Hogan, The Sectarian Strand: Religion in Australian History, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1987

AW Howitt, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1996

S Judd and K Cable, Sydney Anglicans: A History of the Diocese, Anglican Information Office, Sydney, 2000

N Kabir, Muslims in Australia: Immigration, Race Relations and Cultural History, Kegan Paul, London, 2004

M Maddox, God under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005

KR Manley, From Woolloomooloo to 'Eternity': A History of Australian Baptists, Paternoster, Milton Keynes UK, 2006

Jan Morris, Sydney, Viking, London, 1992

PJ O'Farrell, The Catholic Church and Community: An Australian History, revised edition, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1985

R Park, Poor Man's Orange, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1949

MD Prentis, The Scots in Australia: A Study of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, 1788–1900, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1983

J Roe, 'Three Visions of Sydney Heads from Balmoral Beach', in J Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney Studies in Urban and Social History, Hale and Iremonger in association with The Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1980, pp 89–104

J Roe, Beyond Belief, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1986

J Roe, 'Theosophy and the Ascendancy', in J Davidson (ed), The Sydney–Melbourne Book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986, pp 208–17

Suzanne D Rutland, The Jews in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 2005

Suzanne D Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora: Two Centuries of Jewish Settlement in Australia, Collins, Sydney, 1988

P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1973

RC Thompson, Religion in Australia: A History, 2nd ed, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002

L Turnbull, Sydney: Biography of a City, Random House, Sydney, 1999

D Wright and E Clancy, The Methodists: A History of Methodism in New South Wales, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993

Notes

[1] V Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2002

[2] Brian H Fletcher (ed), An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol 1 by David Collins, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1975, first published 1798, vol 1, appendix VI, pp 464–85

[3] Brian H Fletcher (ed), An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol 1 by David Collins, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1975, first published 1798, vol 1, appendix VI, pp 464–85

[4] AW Howitt, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1996, pp 88–508

[5] Lancelot Threlkeld, An Australian Language, Government Printer, Sydney, 1892, pp 47, cited by AW Howitt, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1996, pp 496–97

[6] LR Hiatt, Arguments About Aborigines, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, pp 100–19

[7] Brian H Fletcher (ed), An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Vol 1 by David Collins, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1975, first published 1798, vol 1, pp 258

[8] James Broadbent and Joy Hughes, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 1997

[9] AM Grocott, Convicts, Clergymen and Churches, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1980

[10] James Broadbent and Joy Hughes, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 1997; CH Baker (ed), Historic Buildings, Cumberland County Council, Sydney, 1961, vol 1 Parramatta; vol 2 Central area of Sydney; vol 3 Liverpool and Campbelltown

[11] MD Prentis, The Scots in Australia: A Study of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, 1788–1900, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1983, p 135

[12] James Broadbent and Joy Hughes, Francis Greenway Architect, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 1997

[13] D Wright and E Clancy, The Methodists: A History of Methodism in New South Wales, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, p 18

[14] PJ O'Farrell, The Catholic Church and Community: An Australian History, revised ed, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1985, p 289

[15] S Judd and K Cable, Sydney Anglicans: A History of the Diocese, Anglican Information Office, Sydney, 2000, pp 70–76

[16] Robin Eakin, Aunts up the Cross, Anthony Blond, London, 1965, p 26

[17] J Morris, Sydney, Viking, London, 1992, p 36

[18] KR Manley, From Woolloomooloo to 'Eternity': A History of Australian Baptists, Paternoster, Milton Keynes, UK, 2006, vol 1, pp 3–4

[19] J Roe, 'Theosophy and the Ascendancy', in J Davidson (ed), The Sydney–Melbourne Book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986, p 214

[20] D Wright and E Clancy, The Methodists: A History of Methodism in New South Wales, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, pp 111–14

[21] I Breward, A History of the Australian Churches, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993, pp 93–96, 147–48; I Breward, A History of the Churches in Australasia, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001, pp 377–82

[22] S Emilsen, A Whiff of Heresy, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1990

[23] G Henderson, 'The Catholic Church and the Labor Split', in J Davidson (ed), The Sydney–Melbourne Book, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1986

[24] RC Thompson, Religion in Australia: A History, 2nd ed, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002, p 65; M Hogan, 'The Sydney Style', Labour History, no 36, 1979, pp 39–45; M Hogan, The Sectarian Strand: Religion in Australian History, Penguin Books, Melbourne, 1987

[25] J Roe, Beyond Belief, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1986, p 215

[26] J Roe, 'Three Visions of Sydney Heads from Balmoral Beach', in J Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney Studies in Urban and Social History, Hale and Iremonger in association with The Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1980, pp 89–104

[27] L Turnbull, Sydney: Biography of a City, Random House, Sydney, 1999, p 86

[28] P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1973, pp 193–4

[29] R Park, Poor Man's Orange, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1949, ch 4

[30] Suzanne D Rutland, The Jews in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 2005

[31] Adrian Chan, 'John Young Wai (1847?–1930)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, pp 602–3

[32] Suzanne D Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora: Two Centuries of Jewish Settlement in Australia, Collins, Sydney, 1988

[33] Omar Wafia and Kirsty Allen (ed), The Muslims in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1996; Purusottama Bilimoria, The Hindus and Sikhs in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1996

[34] N Kabir, Muslims in Australia: Immigration, Race Relations and Cultural History, Kegan Paul, London, 2004

[35] M Maddox, God under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005, pp 222–26, 93

.