The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Muir, Thomas

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Muir, Thomas

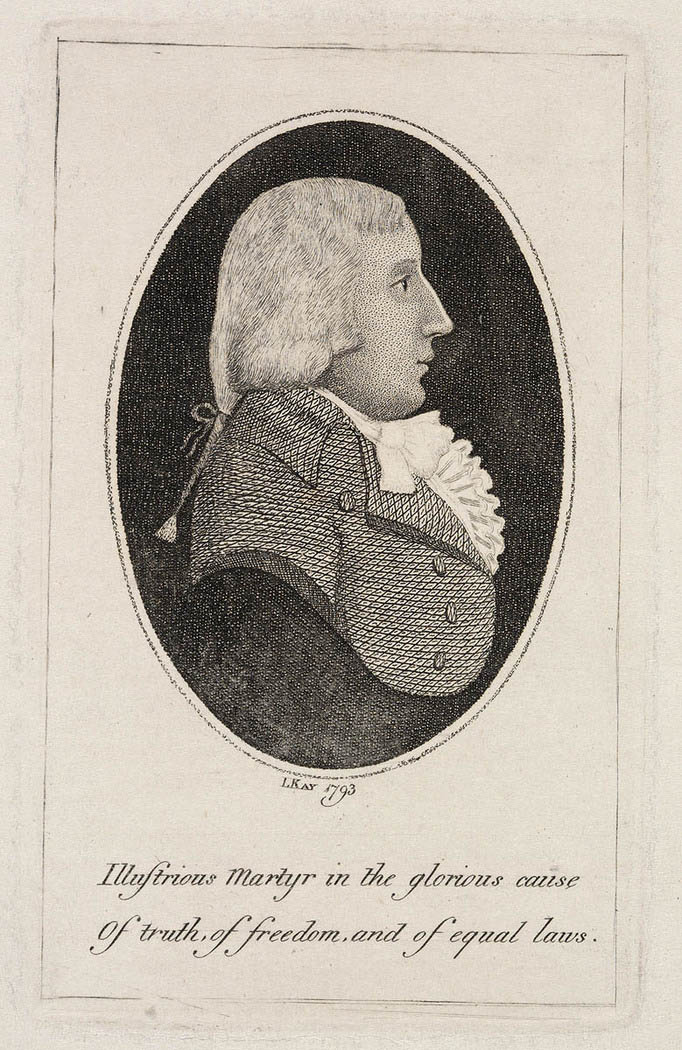

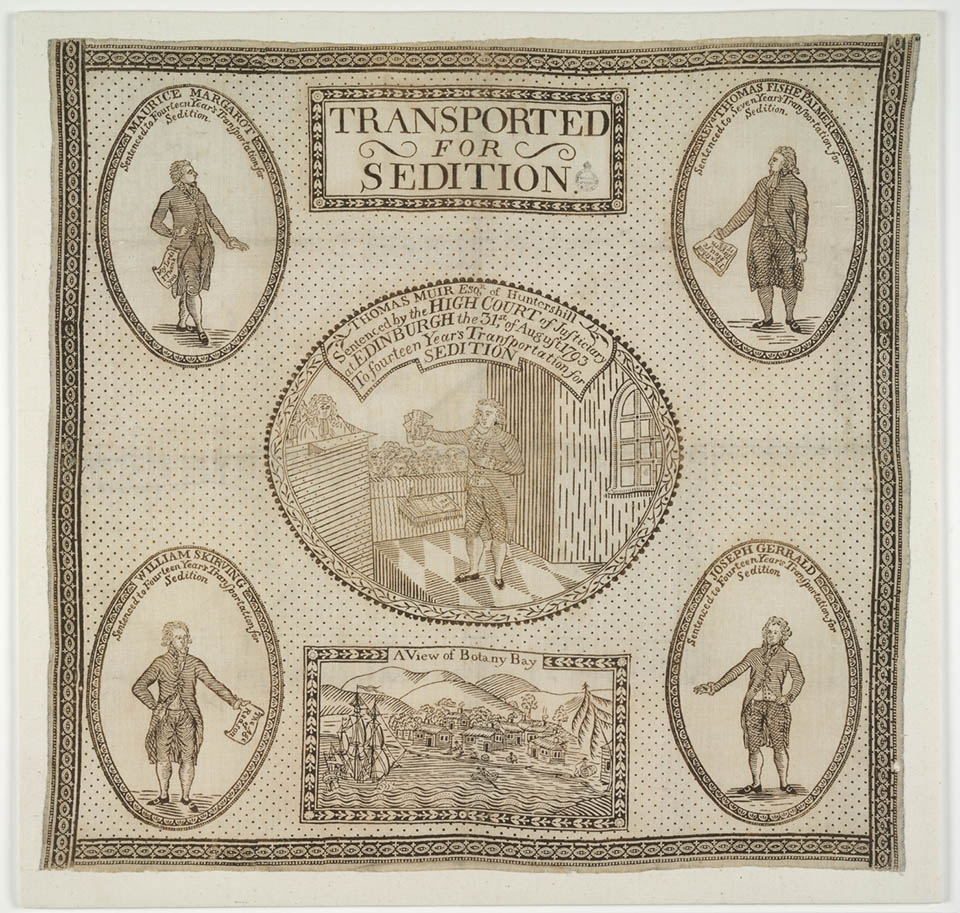

Thomas Muir was the most [media]celebrated of Australia's first political prisoners, five men who became known as the 'Scottish Martyrs'. Campaigning for parliamentary reform, they were sentenced in Scotland for sedition in 1793–94 and transported to Sydney in 1794 and 1795.

The young activist in Scotland

Thomas Muir was a leader in establishing a reform society in 1792, the Edinburgh Society of the Friends of the People, and he became the most inspiring orator of Scotland's fledgling reform movement of the 1790s. A gifted barrister and a young man of principle and polished manners, he fought for the rights of the poor, for electoral reform, universal male suffrage, and freedom of speech. Although he was in communication with the United Irishmen and the French, and shared their reforming zeal, he was not a revolutionary but urged reform by constitutional means. However, this was the era of the French Revolution and a time of paranoia in Britain, when even owning a copy of Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man (1791–92) might be deemed sedition. Muir was accused of inciting trouble through inflammatory speeches, reading out an address from the United Irishmen, and circulating seditious writings, including Paine's book. [1]

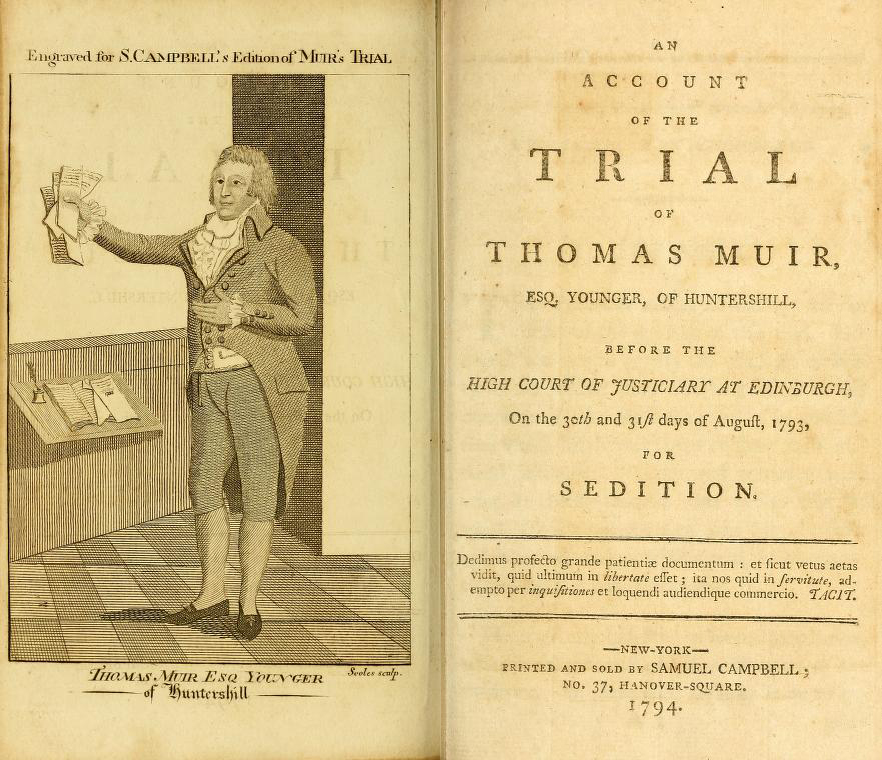

The [media]members of the jury at his trial (30–31 August 1793) found him guilty but were stunned at the extreme severity of his sentence. They had thought that he would receive a few months' imprisonment, but the panel of judges, dominated by the draconian Lord Braxfield, sentenced the 28-year-old Muir to 14 years' transportation, the first time transportation had been imposed for sedition. The trial aroused enormous public interest and a universal outcry abroad. It is believed to have inspired Robert Burns's heroic ode to liberty, 'Scots, wha hae wi' Wallace bled', which was written at the end of August 1793. The transcript of the trial was printed in three editions, two of them in New York, and Muir's three-hour defence speech, published separately, became a best-selling pamphlet.

Transportation to New South Wales

Muir was [media]held prisoner for eight months, some of that time in a prison-hulk on the Thames. Despite strenuous efforts by Whig members of parliament, including the Opposition leader Charles Fox, to have his sentence declared illegal, he was sent to New South Wales on 2 May 1794 on board the transport Surprize. With him went three fellow Scottish Martyrs, William Skirving, Reverend Thomas Fyshe Palmer, and Maurice Margarot. They arrived in Sydney on 25 October 1794. The fifth Martyr, Joseph Gerrald, arrived on 5 November 1795.

Muir and his companions brought money with them and were not treated as felons. Coming ashore in November 1794, they were described by Judge-Advocate David Collins as 'the gentlemen who came from Scotland' and were each given a brick hut, not on the west side of Sydney Cove, where the convicts were housed, but 'in a row on the east side of the cove', the area reserved for civil staff. [2]

Muir's life in Sydney

Two [media]convict servants were assigned to Muir and he was able to purchase land. In a letter of 13 December 1794 to a friend in London, he devotes a short paragraph to his living arrangements:

I have a neat little house here [the brick hut at Sydney Cove], and another two miles distant, at a farm across the water, which I purchased. A servant of a friend who has a taste for drawing, has etched the landscape—you will see it. [3]

The drawing has not survived but is likely to have been by a fellow Scot, Thomas Watling from Dumfries, transported for forgery. At the time, Watling was the most active artist in the colony and servant of Surgeon-General John White, who was a friend of the Scottish Martyrs. [4]

Peter Mackenzie, in his 1831 pamphlet biography of Muir, states, without documentary evidence, that Muir called his farm Huntershill after his father's home in Scotland. [5] This was repeated, and a myth grew up, which still surfaces occasionally, that the Sydney suburb of Hunters Hill derived its name from Muir's old home. In fact the 'district of Hunter's Hill', high land on the north side of Sydney Harbour, was named in government documents before Muir arrived and is accepted as honouring Captain (later Governor) Hunter, who charted the harbour. [6] When the parishes were formed in the 1830s, the name moved south-west and finally settled on the area of today's Hunters Hill. Which direction 'across the water' Muir's farm was situated is not known. Milsons Point has been claimed, but inland from Rozelle Bay has also been proposed. [7] The papers of George Burnett Barton add to the mystery. Dated 1897, they are a draft of a book on 'The Scottish Martyrs', and Barton states emphatically, though without supporting documentation, that Thomas Muir and William Skirving

secured adjoining farms, situated on the north shore of the harbor between the Lane Cove River and Ball's Head. [in his manuscript, Barton underlined this location for emphasis] [8]

In fact there are no official records or title deeds for Muir's purchase of his farm. Neither its precise location, nor its size, nor its name is recorded. The colony's professional chronicler, Judge-Advocate David Collins, simply states that Muir

chiefly passed his time in literary ease and retirement, living out of the town at a little spot of ground which he had purchased for the purpose of seclusion. [9]

Despite the privileges offered them, the Scottish Martyrs were told by Lieutenant-Governor Grose upon their arrival that it was 'absolutely requisite' that they 'avoid on all occasions a recital of those politicks' that had brought them to their present 'unfortunate situation'. [10] There is no evidence that Muir aired his ideas on liberty in Sydney. Acutely conscious of his reputation as a champion of liberty and of the cosmopolitan reach of his ideology, to be thus forcibly silenced, living on a little patch of bushland away from the public eye, must have been a profound culture shock to the brilliant young orator of Scotland's reform movement who prided himself on being 'a citizen of the world'. [11]

However, this canny Scot quickly got the measure of the place and occupied himself with trading. Not classed as ordinary convicts, the Martyrs were not required to work but they were not entitled to any provisions from the government stores. They had to support themselves, and the lengthiest paragraph of Muir's letter to his friend in London of 13 December 1794 is a request that,

When any money is transmitted, cause a considerable part of it to be laid out at the Cape or Rio Janeiro, in rum, tobacco, sugar, &c., &c., which are invaluable, and the only medium of exchange. . . . In a country like this, where money is really of no value and rum everything, you must perceive the necessity of my having a constant supply by every vessel.

He continues, detailing the profits he is able to make in Sydney, for example,

For a goat I should pay in money £10 sterling; now for less than eight gallons of spirits, at 18d the gallon, I can make the same purchase.

There is some evidence that Muir exercised his legal skills while in the colony. The same letter mentions that he is writing a defence of Palmer and Skirving. They had been accused of mutiny on board the Surprize, as a result of which they had cut off relations with Maurice Margarot: 'Skirving, Palmer and myself live in the utmost harmony. From our society Margarot is expelled'. It is likely that the following year Muir also advised his friend John Boston in the first civil law suit in the colony (Boston won against the military). [12] Muir was deeply religious – he had been an Elder of his local Presbyterian church in Scotland – and reportedly spent time copying passages from the Bible for distribution among the convicts. [13] His true vocation, however, as a political reformer was quashed.

Continuing Tory unease about Muir

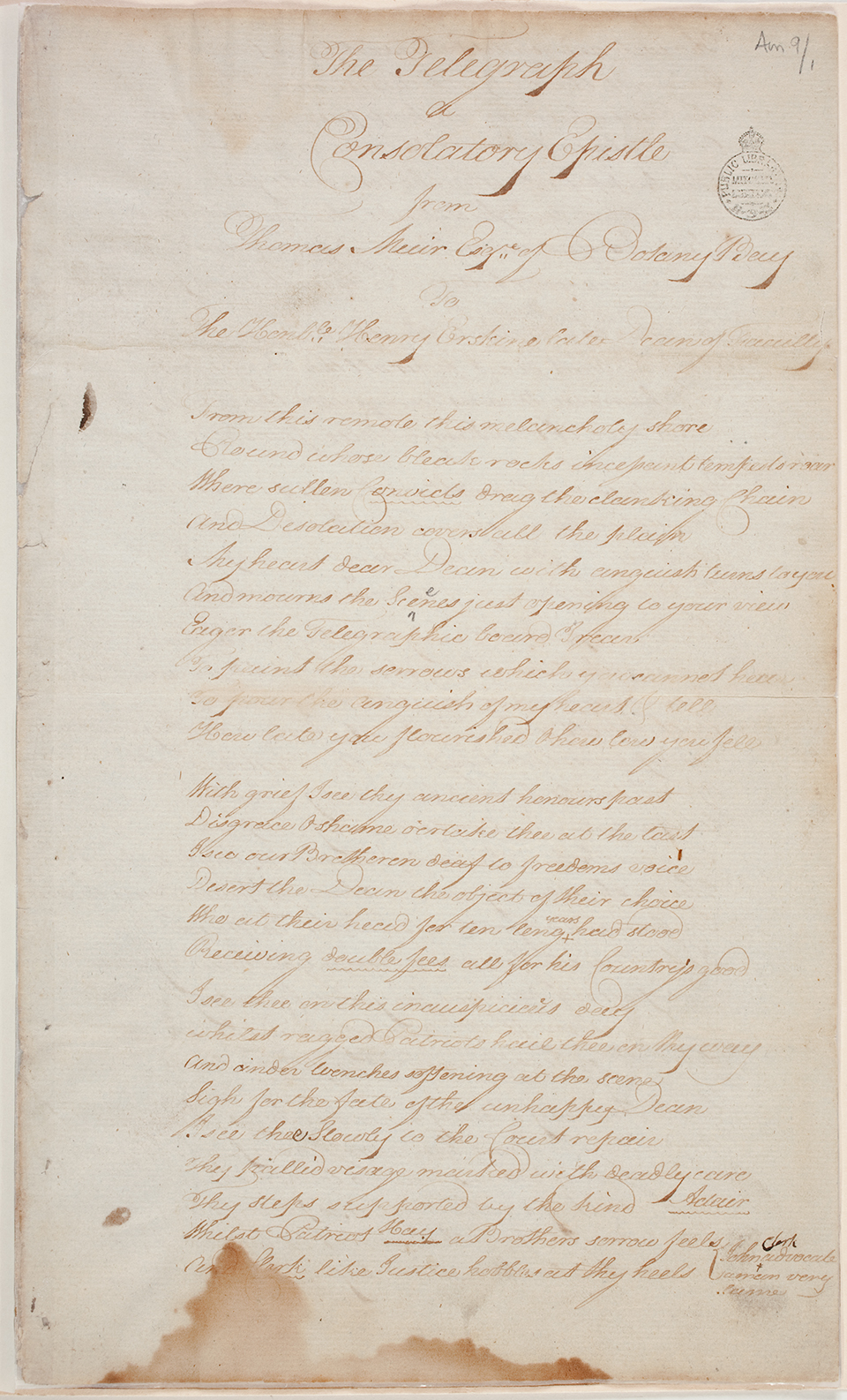

Muir's life in Sydney was [media]thus uneventful politically, yet even from these far-flung shores the spectre of Muir bothered the Tory establishment in Britain. This is evidenced in a unique and intriguing manuscript held in Sydney's Mitchell Library, 'The Telegraph: A Consolatory Epistle from Thomas Muir Esq. of Botany Bay to The Hon. Henry Erskine, late Dean of Faculty'. Purporting to be written by Muir, it was actually printed anonymously in Edinburgh in January 1796 and is thought to be the work of a Tory clergyman. [14] Exactly how the manuscript, in beautiful handwriting, dated 1796 and water damaged, came to the Mitchell Library remains unknown. [15] Someone must have painstakingly copied it from the printed work and sent it out, presumably to amuse the society of Sydney and to discredit Muir, for it is a full-blown political satire. It was taken seriously by Robert Hughes in The Fatal Shore as the bona fide work of Muir, [16] but Muir could not possibly have written it, if only because the news of Henry Erskine's fall would not have reached Sydney for at least five months, by which time, as we shall see, Muir was well out of the colony.

The speaker of the poem is 'Muir', and he lashes himself with the harshest satire in 192 lines of heroic couplets. It is shaped as a letter to his friend Henry Erskine, deposed from his position as Dean of the Faculty of Advocates in Edinburgh on 12 January 1796. Muir urges Henry to 'come to this sacred shore' (line 74) and bring with him their Whig friends. Interestingly, only their initials appear in the printed version but their full names are written in the manuscript. Ten are named, including leading Scottish reformers Colonel Norman Macleod and the Earl of Lauderdale.

Muir presents himself as communicating with Henry via the new telegraphic technology (lines 1-7):

From this remote, this melancholy shore;

Round whose bleak rocks incessant tempests roar;

. . .

Eager the Telegraphic board I rear,

Invented by the Frenchman Claude Chappe in 1792, the télégraphe was a system of signals from horizontal moveable boards attached to raised posts. It enabled messages to be relayed over long distances, and it aroused fears that Jacobin messages might be sent between revolutionary France and Britain. By the end of the poem, Muir looks forward to an afterlife in Satan's domain, where he hopes that he and his Whig companions might raise 'A France in Hell, that rais'd a Hell in France' (line 175). [17]

A telegraph from Botany Bay to Edinburgh was clearly poetic licence, but the poem is evidence of continuing Tory anxiety about the circulation of revolutionary information and of Muir's radical ideas about 'the sacred Rights of Man' and 'lov'd democracy' (lines 64, 171). It is driven by a determination to eradicate him together with his associates back in Scotland.

Muir's escape

Ironically, when The Telegraph was published in January 1796, Muir was about to escape from New South Wales. The year 1795 had shown him the realities of the place: the administrator, Captain William Paterson, allowed the army to take the law into their own hands, the mania for spirits continued unabated, bloodshed occurred between the Aborigines and the settlers, criminal courts were regularly called, there were severe shortages of food, and burglaries were rife. Collins reports that in July

the house occupied by Mr. Muir was broken into, and all or nearly all that gentleman's property stolen: some of his wearing apparel was laid in his way the next day; but he still remained a considerable sufferer by the visit. [18]

In 'literary retirement', Muir set to work to draft a legal argument justifying his departure, and as soon as the new Governor, John Hunter – the most eminent Scot in the colony – arrived in September, he prepared to submit the argument to him as a petition on behalf of Palmer, Skirving, and himself.

Hunter interviewed the Scottish Martyrs individually in October and they made a good impression upon him. He wrote to a friend in Leith,

Muir was the first I saw; I thought him a sensible, modest young man, of a very retired turn, which certainly his situation in this country will give him opportunity of indulging; he said nothing of the severity of his fate, but seemed to bear his circumstances with a proper degree of fortitude and resignation. [19]

In fact this 'resigned' young man had his skilful petition all ready in his own handwriting, dated 14 October, and he delivered it to Hunter. [20] He argued carefully, drawing on the authority of the Earl of Lauderdale and Sir George Mackenzie, that the extent of their sentences was banishment and that they were within their legal rights to depart from New South Wales whenever they wished, provided they did not return to Great Britain. Hunter was persuaded, and he wrote to the Home Secretary, enclosing the petition. 'I am obliged to confess, my Lord', he wrote,

that I cannot feel myself justifiable in forcibly detaining them in this country against their consent. … Although they have not in their power to return to any part of Great Britain but at the risk of life, they probably might have a desire to pass their time in Ireland. [21]

As soon as an opportunity presented itself after this petition to Hunter, Muir left Sydney. The Scottish historian Michael Donnelly plausibly suggests that he had bought his place across the water not because he had a taste for farming but 'with an eye to ultimate escape':

By this means he was able to remove himself from the direct observation of the Governor and his soldiers, and at the same time was provided with a legitimate excuse for keeping a small boat. [22]

It was by [media]means of a rowing boat that he managed to escape. When an American ship, the Otter , put into Sydney for supplies on 24 January 1796, Muir persuaded the captain to take him on board when the ship left. So, 16 months after his arrival in Port Jackson, Muir and his two convict servants rowed out through Sydney Heads on the night of 17 February 1796 and 'about the middle of the next day' were picked up by the Otter 'at a considerable distance from land'. [23]

Muir left a letter for the Governor justifying his escape and explaining that he 'purposed practising at the American bar as an advocate', and Hunter dispassionately reported his departure to the Duke of Portland. [24] In August 1796 the Duke finally replied to Hunter's original question about Muir's petition. His letter would have arrived five to six months later and it set Hunter straight: the Scotsmen were not permitted to go to Ireland, nor could they leave New South Wales until they had served the full term of their sentences. [25] By this time, Muir was on the other side of the world.

Muir's journey to Europe via America

After his voyage on the Otter across the little-known Pacific to Vancouver Island, Muir transferred to a Spanish ship which took him to Spanish California. He wrote letters from Monterey to his parents and friends and also to Charles Fox and the earls of Lauderdale and Stanhope; he described Port Jackson as 'that remote & horrid region', 'forlorn dismal, & inhospitable'. [26] In a long screed to George Washington he recounted his escape and journey, laying out his plans for life in America and seeking the General's help. None of his letters were delivered, as they were confiscated by the Spanish. Thereafter his journey became a nightmare and his hopes for a career in America were dashed.

From California he was taken to Mexico, where he came under the Spanish authorities, was transported to Havana in November 1796 and imprisoned there. In March 1797 he was put on another Spanish ship bound for Spain and was caught in a sea battle between England and Spain off Cadiz. His face was badly wounded and he lost his left eye; he was then hospitalised in Cadiz. Finally he was allowed to go to France in November 1797, where he was given a hero's welcome in Bordeaux. For several months he was fêted in Paris, where he spent his time meeting with fellow radicals, among them Tom Paine and Wolfe Tone, and submitting long advisory papers to the French government. However, his popularity declined and, weakened by his wounds, impoverished, and critically depleted by nearly six years of trauma, he died in obscurity at Chantilly outside Paris on 26 January 1799, aged 33.

He was a tragic and heroic figure and ripe for myth-making from the start. The first foray of this kind was an account published in Paris in 1798 entitled Histoire de la Tyrannie du Gouvernement Anglais Exercée Envers le Célèbre Thomas Muir, Ecossais. It claimed to be based on conversations Muir had in Bordeaux, upon his arrival in France, with a M Mazois, merchant. In 1990 it was translated into English by Jonathan Wantrup, who believes that it 'has the circumstantial ring of truth'. [27] It includes a 'Brief Account of Botany Bay' – population, government, native inhabitants, native animals – which, the French editor declares, 'word for word and without exaggeration, is what Thomas Muir has related'. [28] In fact much of this account is lifted from Watkin Tench's Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay (London, 1789), as Wantrup acknowledges. Some details cohere with the known facts, such as Muir's escape through Sydney Heads and picking up by the Otter the next day, but much is added embroidery, such as the story that George Washington sent the Otter to rescue Muir, a myth further embroidered by Mackenzie in his unreliable biography.

The legacy of Muir

What is not myth, however, is Muir's work in Scotland, Ireland, and France. He was a radical ahead of his time, a champion of human rights, and a hero of the dispossessed and the downtrodden, people who had no vote. As Donnelly records, he was 'prepared to take on the most unrewarding and difficult cases' in his practice as a lawyer, 'foregoing a fee when petitioned by a destitute client', and his trial was 'a classic example of the political abuse of the judicial process'. [29] His career was savagely cut short but his campaign for parliamentary reform in the early 1790s and the wide publicity over his trial and sentence sowed the seeds of Scottish democracy. With the passing of the Great Reform Bill in 1832, the advance of democracy was assured, and the sacrifice of Muir and his companions was eventually recognised and commemorated. Monuments were erected to the Scottish Martyrs in 1845 at Edinburgh's Calton Hill cemetery and in 1852 at Nunhead Cemetery, London.

In the twenty-first century, Muir is [media]more personally and warmly remembered at Bishopbriggs, a suburb of Glasgow where his ancestral home Huntershill still stands. [30] This is the headquarters of a Scottish charity established in 2010, the Friends of Thomas Muir. Linking Muir with William Wallace and Robert the Bruce – 'champions of freedom' – the group is committed to recovering his reputation and promoting him as a 'champion of democracy'. [31] In 2010 some of the members of the group visited Australia in this cause.

During his time in Australia, being silenced by the government, Muir did not contribute to the advancement of democracy, but he is part of our British heritage and the Museum of Australian Democracy in Canberra rightly has an exhibit on him. The Museum honours him as the father of Scottish democracy and has on permanent exhibition a posthumous bust of Muir made in 2008 by the Scottish sculptor Alexander Stoddart. It is a bronze cast of Stoddart's plaster sculpture in the Bishopbriggs Library and portrays Muir with his left eye and cheek covered with a drape.

Muir's life, so full of promise, was tragically destroyed, and one cannot help but wonder, if he had known the dreadful fate in store for him, whether he might not have stayed in Sydney and contributed his skills as a lawyer to the infant colony. A long life in 'that remote & horrid region', though, would doubtless have seemed a fate worse than death. In leaving he believed he was exercising his legal right to freedom and in reaching France he was able to reanimate, if briefly, his political life and his cosmopolitan identity. His place in history is assured as a 'martyr' for liberty. In his speech during his trial in the High Court of Judiciary, Edinburgh on 30 August 1793, he said,

I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause – it shall ultimately prevail – it shall finally triumph. [32]

Today we take for granted the freedoms and the democratic rights Muir fought for.

References

Christina Bewley, Muir of Huntershill, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981

Michael Donnelly, Thomas Muir of Huntershill, Bishopbriggs, Bishopbriggs Town Council, 1975

John Earnshaw, Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959

Notes

[1] Christina Bewley, Muir of Huntershill, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981, pp 68–69. Bewley's book is the fullest history of Muir and his times. For a general study of the Scottish Martyrs, see Frank Clune, The Scottish Martyrs: Their Trials and Transportation to Botany Bay, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1969; see also Tony Moore, Death or Liberty: Rebels and radicals transported to Australia 1788–1868, Murdoch Books, Millers Point NSW, 2010, chapter 1. An ABC Radio National Hindsight programme entitled The Trials of Thomas Muir was made in 2011 with speakers from Scotland and Australia. The programme is accessible as a podcast at http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/hindsight/the-trials-of-thomas-muir/3717128, viewed 2 February 2012

[2] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, 1798; reprinted in facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 399; Historical Records of Australia Series 1, vol 1, Government Printer, Sydney, 1914, p 772. Early drawings and watercolours of Sydney Cove from 1793–96 give a good idea of the arrangement of huts on the east side of the cove: see Tim McCormick et al, First Views of Australia 1788–1825: A history of early Sydney, David Ell Press, Chippendale, 1987, plates 26, 30, 32, 34–39. From evidence given in a law suit, John Earnshaw calculates that the Scottish Martyrs' huts 'stood midway along the present day O'Connell St' – Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959, p 17

[3] Published in the London Morning Chronicle 29 July 1795. Extracts of the letter were reprinted in Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, pp 869–70

[4] John Earnshaw, Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959, p 19. A letter of Thomas Fyshe Palmer, 15 September 1795, is evidence of Palmer's confidence in White – Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, p 880. White was also a naturalist and is almost certainly the unnamed 'most valued friend' described by Palmer in his earlier letter of 15 December 1794 – Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, p 871

[5] Peter Mackenzie, The Life of Thomas Muir, WR McPhun, Glasgow, 1831, p 33. Mackenzie's biography is generally regarded as unreliable

[6] Beverley Sherry, 'Thomas Muir and the Naming of Hunter's Hill', Hunters Hill Trust Journal, vol 47 no. 2, October 2009, pp 3–6. See also Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Balmain (NSW), 1989, pp 20–21

[7] James Scott, 'The Scottish Martyrs' Farms', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 46 Part 3, 1960, pp 161–68. John Earnshaw acknowledged that there is no record of Muir's purchase but deduced that his farm must have been at Milsons Point – Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959, p 18

[8] George Burnett Barton papers, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library, DLMSQ 107

[9] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, 1798; reprinted in facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 457

[10] Letter from Grose to the Rev. T.F. Palmer, 26 October 1794, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, p 868

[11] He identified himself thus, in Latin, in a book he inscribed and presented to the Antonine monks at Rio de Janeiro when the Surprize stopped there on the way out to Australia – Christina Bewley, Muir of Huntershill, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981, p 114–15

[12] Christina Bewley, Muir of Huntershill, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981, p 128. For a record of this protracted case over more than three weeks in December 1795, see Hunter's dispatch, Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 1, Government Printer, Sydney, 1914, pp 603–43

[13] Samuel Bennett, History of Australian Discovery and Colonisation, Hanson & Bennett, Sydney, 1865, p 203. This history began as weekly chapters in the Empire newspaper and the myth that the suburb of Hunters Hill was named by Muir perhaps began with Bennett. Hunters Hill was established as a municipality in 1861, around the time Bennett was writing, and he states, without documentary evidence, that Muir 'purchased some land on the north shore of the Parramatta River [yet another furphy], and named the place Hunter's Hill, after his patrimonial estate in Scotland. That locality, now a beautiful and populous suburb of Sydney, still bears the name he conferred, and serves as a memorial of one of the noblest men that ever landed on Australian shores' (p 203). George Barton's 'Scottish Martyrs' consists of articles written in the 1880s for the Sydney Evening News, a newspaper begun by Bennett. While repeating the myth of Muir and the suburb of Hunters Hill, he claimed a different location for Muir's farm, 'between the Lane Cove River and Ball's Head', underlining the location perhaps as a correction to Bennett's earlier claim

[14] The catalogues of the Bodleian Library, British Library, and National Library of Scotland all state that the author is George Hamilton, Minister of Gladsmuir. The printed copy I have used, in the Rare Books collection of the University of Sydney library, has been signed on the title page by a John Rutherford Jun., who has also written at the bottom of the page, 'Supposed to be wrote by Henry Mackenzie Author of The Man of feeling'. Mackenzie was a zealous Tory

[15] After extensive search, the Mitchell Library has been unable to trace the provenance of the manuscript; the catalogue card states, 'Muir, Thomas Pseudonym'

[16] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: a history of the transportation of convicts to Australia, 1787–1868, Collins Harvill, London, 1987, pp 178–79

[17] For a detailed investigation of the political implications of the work, see Nigel Leask, 'Thomas Muir and The Telegraph: Radical Cosmopolitanism in 1790s Scotland', History Workshop Journal, vol 63 no 1, 2007, pp 48–69. Leask believes that the manuscript is a copy of the printed poem. There is a discussion of The Telegraph by Nigel Leask and myself as an add-on to the ABC radio programme referred to in note 1 above, available online at http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/hindsight/muir-poem-discussion/3731444, viewed 2 February 2012

[18] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, 1798; reprinted in facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 422

[19] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, p 882

[20] Reproduced in entirety in Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, pp 883–85

[21] Governor Hunter to the Duke of Portland 25 October 1795, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893, p 883

[22] Michael Donnelly, Thomas Muir of Huntershill, Bishopbriggs, Bishopbriggs Town Council, 1975, p 18

[23] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, 1798; reprinted in facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 457; JS Cumpton, Shipping Arrivals and Departures Sydney 1788–1825 Parts I, II and II, Canberra, ACT, 1964, p 31. The quotation is from Muir's own account in his letter to General Washington, President of the United States, from Monterey 15 July 1796, reproduced in John Earnshaw, Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959, pp 59–61

[24] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, London, 1798; reprinted in facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 457; Hunter to Portland 30 April 1796, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 3, Government Printer, Sydney, 1895, p 47

[25] Portland to Hunter, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 3, Government Printer, Sydney, 1895, pp 98–99. In the same volume, see the long letter by Robert Dundas to Portland, 5 September 1796, rebuking Hunter and defending the judgement of the Scottish court. Dundas had conducted the prosecution at Muir's trial in 1793

[26] John Earnshaw, Thomas Muir Scottish Martyr, Stone Copying Company, Cremorne NSW, 1959, pp 59, 64, 68. Muir's letters from Monterey, preserved in the Archives of the Indies in Seville, are printed as Appendix 2 of Earnshaw's book

[27] Jonathan Wantrup, The transportation, exile and escape of Thomas Muir: a Scottish radical's account of Governor Hunter's New South Wales published at Paris in 1798 / translated from the French with introduction and notes, Boroondara Press, Melbourne, 1990, p 12

[28] Jonathan Wantrup, The transportation, exile and escape of Thomas Muir: a Scottish radical's account of Governor Hunter's New South Wales published at Paris in 1798 / translated from the French with introduction and notes, Boroondara Press, Melbourne, 1990, p 41

[29] Michael Donnelly, Thomas Muir of Huntershill, Bishopbriggs, Bishopbriggs Town Council, 1975, pp 7, 13. See also Donnelly's essay on Muir in Joseph O Baylen and Norbert J Gossman (eds), Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals, vol 1: 1770–1830, Harvester Press, Hassocks (Sussex), 1979, pp 330–34, in which he notes that Muir's trial 'has passed into legal history as a classic example of the abuse of the judicial process for political ends' (p 332)

[30] See Beverley Sherry, 'A Visit to Thomas Muir's Huntershill, Scotland', Hunters Hill Trust Journal, vol 49, no 1, 2011, pp 1, 4–5. Muir has also been espoused by the Scottish National Party

[31] See the Friends of Thomas Muir website, www.thomasmuir.co.uk, viewed 2 February 2012

[32] Cited in Christina Bewley, Muir of Huntershill, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1981, p 79

.