The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Greeks

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Greeks

The term 'Hellenes' is used for all those people who identify with Hellenic language and culture, and while most Hellene migrants to Sydney originated from the areas that now constitute the Hellenic Republic (known in English as Greece), substantial numbers arrived from countries such as Cyprus, the former Soviet Union and Egypt, as well as the territories that now constitute the Republic of Turkey.

Smaller groups of Hellenes have come from New Zealand, South Africa, Israel/Palestine and Romania. Hellenes have arrived in Sydney with Hellenic, Cypriot, British, Italian, Turkish, and many other travel documents, settling in Sydney from around the world for political, economic and personal reasons.

Origins

The Australian Hellenic community traditionally dates its origins to 27 August 1829. On that day, seven young men, who had been convicted of piracy, arrived in Port Jackson aboard the Norfolk. Two years earlier, these sailors from the Aegean island of Hydra, in the Saronic Gulf, west of Athens, had stopped the Alceste (a Maltese-owned British vessel) in the waters south of Crete and taken some items they thought would be useful. The British vessel had been transporting supplies to the Egyptian port of Alexandria, then in the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Antonis Manolis, Damianos Ninis, Ghikas Voulgaris, Georgios Vasilakis, Konstantinos Stroumboulis, Nikolaos Papandreou and Georgios Laritsos were not pirates, but pallikarria, freedom fighters in the Hellenic War of Independence.

The seven Hellenes were assigned to various settlers around the Sydney colony: Ninis in the shipyards of Sydney harbour, Manolis to the vineyards on the estate of William Macarthur at Camden, Laritsos to Major Druitt of Mount Druitt, Stroumboulis to FA Hely (later Principal Superintendent of Convicts), Vasilakis to Mr Macalister of Argyle, and Voulgaris to Alexander Macleay, the Colonial Secretary. Setting the model for the hundreds of thousands of Hellenes who followed them, the Hydran sailors used the skills learnt in their island home to develop and enhance what became their new home.

Following their pardons in December 1836, five elected to return to a now independent Hellenic Kingdom, while Ghikas Voulgaris and his Irish-born wife, Mary Lyons, became pioneer settler-graziers in the Monaro district of south-eastern New South Wales. He lies in the Old Nimmitabel Cemetery, near Cooma. His descendants bear names like Bulgary, Macfarlane, McDonald and Stewart, and are scattered across the globe. Antonis Manolis spent his remaining years in the Picton district, south-west of Sydney, and is buried in the town's Old Anglican Cemetery, overlooking the fields he had cultivated for decades.

[media]The first female Hellene settler to reach Sydney was born Aikaterine Plessos in the Epiros region of north-western Hellas. Like so many Hellenic women who followed her, her husband's career path brought her to Sydney. Raised by her mother in the regional capital, Ioannina, her extraordinary life included betrothal to Dr Ioannis Kolettis (a future Prime Minister of the Hellenic Kingdom), meeting Lord Byron in the town of Mesolonghi, fleeing to the British-occupied Ionian Islands, marrying Major James H Crummer, a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, moving to England, Ireland and the colony of New South Wales in turn, and outliving her husband and nine of their eleven children. Between her husband's death in 1867 and her own on 8 August 1907, Catherine Crummer lived in the Kings Cross area of eastern Sydney. She lies today in a family grave [media]in Waverley Cemetery. [1]

Early organisations

Once a sufficient number of Hellenes had arrived in the Australian colonies, communities began to form in the two major centres of Sydney and Melbourne. The Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales (GOC), Sydney's oldest Hellenic organization, was established in 1898.

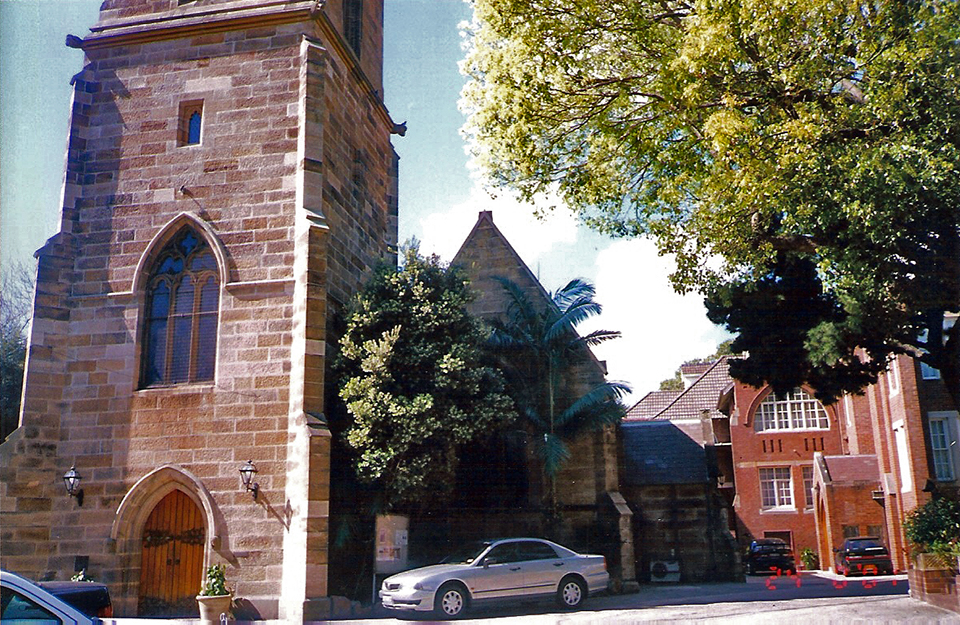

A year later, the combined effort of Hellenic and Arabic-speaking Orthodox faithful produced the first Orthodox Church in the southern hemisphere: Ayia Triada (Holy Trinity), in Bourke Street, Surry Hills. [2] [media]The first resident Orthodox priest in Australia was despatched by the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Born in the town of Madytos (also known as Maidos, modern Eceabat) on the Gallipoli Peninsula and educated in Jerusalem, Father Serapheim Phokas took up the position at Ayia Triada.

A steady flow of migrants, mostly from Megisti (Castellorizo), Kythera (also known as Cerigo) and other islands of the Aegean and Ionian seas, arrived in Sydney but largely scattered to rural centres around New South Wales and Queensland. Chain migration led new arrivals to join relations or compatriots in established businesses, particularly in the omnipresent 'Greek Cafe' of the local country town.

Trouble at home

The second decade of the twentieth century was a time of great turmoil for the Sydney Hellenic community. Three conflicts in the eastern Mediterranean had a great impact on Hellenes worldwide: the Balkan Wars (1912–13), World War I (1914–18) and the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22).

Sydney's Hellenes responded to the call for aid. A small number returned to their places of birth to enlist in the Hellenic armed forces. Others chose to enlist in the armed forces of their adopted homeland, serving on the battlefields of the Gallipoli Peninsula, the Western Front and elsewhere. Large sums of money and quantities of supplies were also assembled by the Sydney Hellenic community and despatched to the families they had left behind. For example, during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, £255 was raised, partly to fund 'volunteers to Greece to take part in the hostilities against the Turks'. Sydney's Hellenic community were also described as being 'willing to subscribe a further sum to the same cause'. [3]

Victory in the Balkan Wars and World War I produced Greece's greatest expansion since its creation in 1830. Southern Epiros, Macedonia, Thrace and the Aegean Islands and their large Hellenic populations were brought within the bounds of the Hellenic state. There was much for Australian Hellenes to celebrate, as optimism for the future abounded.

But dark clouds were already gathering. The Great War brought to the surface deep political divisions within Hellenic society. The supporters of the pro-British Prime Minister, Eleutherios Venizelos, opposed the pro-German attitudes of the King, Konstantinos. Inevitably, the political struggle in Hellas impacted on the Hellenic community of Sydney. Between 1914 and 1916, Hellas maintained a neutral stance as the stalemate between Venizelos and the King dragged on.

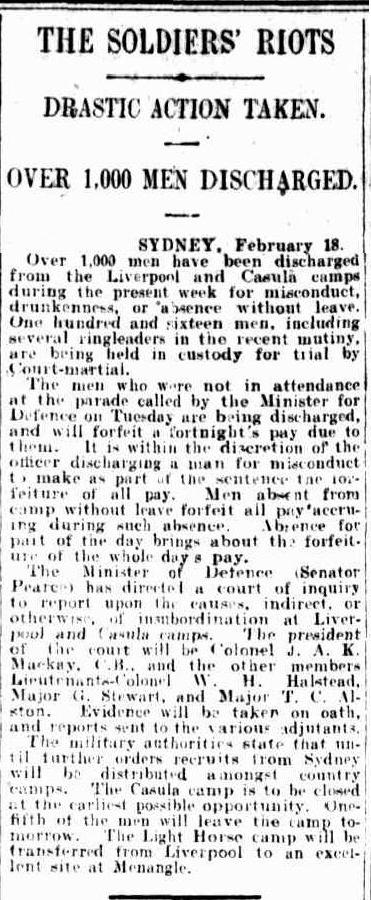

Because of the pro-German position of the King (partly due to the fact that his wife was the sister of Kaiser Wilhelm II), Sydney's Hellenes were viewed with suspicion by the Australian authorities and many Australians. [media]During the infamous 1916 riot by a mob of drunken Australian army recruits from the Liverpool barracks, the businesses of Hellenic migrants came in for particular attention. [4]

This occurred despite public declarations by the Hellenes of New South Wales. They had sent a petition to the State Commandant 'to form a company in the Australian Expeditionary Forces'. The community sought to do this as 'some slight return for the noble manner in which Great Britain has stood by' Hellas. [5] Later in 1916, community leader John Comino wrote to Prime Minister Venizelos, stating that the Hellenes of New South Wales 'were declared friends of the Allies from the commencement of the war'. [6]

Matters in Hellas came to a head when Prime Minister Venizelos left the capital, moved to the country's second city, Thessalonike, and proclaimed the formation of a Provisional Government that would be taking the country into World War I on the side of the Allies. The King was forced into exile, and any suspicion of disloyalty to the British Crown was lifted from Sydney's Hellenic community. Mr (later Sir) Samuel Cohen, who had resigned his commission as Consul-General of the Hellenic Kingdom in protest at King Konstantinos's pro-German stance, was immediately re-appointed by Venizelos. [7]

'Remember the Greek and Armenian Refugee Children'

From January 1914, the government of the Ottoman Turkish Empire embarked on a systematic campaign to extinguish the indigenous Hellenic, Armenian and Assyrian presence in the lands under its dominion. This campaign became known as the Hellenic, Armenian and Assyrian genocides (1914–24).

[media]The Sydney Morning Herald, the Daily Telegraph and other Australian newspapers regularly carried news items on the latest atrocities suffered by the Hellenes and Armenians still under Ottoman Turkish rule: 'Turks Massacre Christians', 'Greeks Fear Massacre' and 'Menace of Massacre'. [8] This was particularly poignant for the Sydneysiders who had family or commercial ties to cities in Anatolia, such as Smyrne (modern Izmir), Phokaia (modern Foca), Mersine (modern Mersin) and Adana.

Returning ANZACs, held as prisoners-of-war throughout the Ottoman Turkish Empire, confirmed the media reports; their prisons had been the homes, schools, churches and monasteries of the Hellenes, Armenians and Assyrians systematically massacred by the forces of the Ottoman government. [9] Sydney became a major centre of the international relief efforts for the genocide survivors scattered throughout the Near East. [10] As early as 1916, there had been calls from London for the creation of a Sydney committee, due to the number of donations from the Harbour City to the London Lord Mayor's Fund. [11]

The Armistice came into force on 11 November 1918. Only weeks later, the Lord Mayor, J Joynton Smith, called a public meeting in the vestibule of the Town Hall for Thursday 12 December. The purpose was to form 'a Committee to raise Funds for the relief of the suffering' Armenian, Hellene and Assyrian genocide survivors. [12] The meeting was duly held and a resolution forming the committee under the patronage of the Lord Mayor was adopted. From the outset, the Fund's work was concentrated on the survivors scattered around Syria and Greece.

The first official meeting of the Executive Committee of the Lord Mayor's Armenian Relief Fund was held on 13 January 1919. With Lord Mayor Richard Watkins Richards as President, the Executive Committee included prominent religious and secular leaders of Sydney. Some of those mentioned in the surviving documentation of the Fund included Bishop Dr Pain and Archdeacon D'Arcy Irvine (Anglican Church), Reverend Nicholas John Cocks (Congregational Church, Pitt Street), WG Crane (President of the Young Men's Christian Association), and William M Brooks, MLC.

The arrival of Dr Lincoln Wirt, representative of the New York-based Near East Relief Organisation led to the merger of the relief efforts Australia-wide into the Australasian Armenian Relief Fund. Fresh major appeals were held on 11 August 1922, particularly in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Lord Mayor William Percy McElhone appealed to the 'Citizens of New South Wales' to 'gather a cargo of 4,000 tonnes':

The things most needed are wheat, flour, rice, tinned milk, tinned meat, sugar, cocoa, coffee, cheese, chocolate, dried and preserved fruits, corn, oats, bacon, hams, soap, etc, leather, wool, woolen and cotton material, and any second hand clothing. [13]

Even seed was sent to enable the agriculturists amongst the refugees to revive cereal production. [14]

In October 1922, the President of the Republic of Turkey decreed the expulsion of all 'non-Muslims' from the territory under his control. The irony was that most of these people had already fled. In return, many Muslims were obliged to leave Hellas. This was euphemistically named the 'Exchange of Greco-Turkish Populations'. By the time of its conclusion in 1925, 1.4 million Christians had flooded into Greece. Their needs overwhelmed the society, and the international community – including Sydney – responded to the appeal for aid.

Australian Orthodoxy

In many ways, the pattern of settlement of Hellenes in the greater Sydney region can be charted by the creation of Orthodox churches, between the first one in 1898 and the most recent one in 2008. Beyond the religious aspects, the Orthodox churches serve as communal focal points: secular functions, such as commemorations of historic events, departures of tour groups and birthday parties, are held either in cooperation with the parishes or in the church halls.

The unprecedented loss of life in the Near East in the 1910s and 1920s led to a radical shift within the ranks of the Orthodox churches. The churches in Australia had been de facto under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. In March 1924 the Oecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople (modern Istanbul), assumed jurisdiction over the Greek Orthodox churches in the Antipodes. Dr Christophoros Knitis, Metropolitan of Serres, a city in eastern Macedonia, was appointed the first Archbishop of Australia and New Zealand, with a flock of approximately 5,000 people.

Ostensibly, the division occurred between those who believed that the community was not large enough to support an Archdiocese and those who believed this institution was desirable. In essence, though, the split began as a power struggle between the pro- and anti-Archdiocese factions for a position of dominance. [15] This is a very simplified interpretation of a very complex issue involving ecclesiastical jurisdictions, control over communal property and positions of leadership within the community. As discussed later, following World War II, the split took on a partisan ideological dimension that was only healed in the middle of 2011.

The Hellenic Club of Sydney, a body representing the supporters of the new Archbishop, was established in 1924. Archbishop Christophoros led religious services in rented premises (in St Michael's Anglican Parish Hall, Darlinghurst, less than a kilometre away from Ayia Triada in Bourke Street) while fundraising began for the erection of the Cathedral of Ayia Sophia (Divine Wisdom). Property on South Dowling Street, Paddington, was purchased from the Jewish community and a foundation stone laid in 1927. [media]The following year, the Cathedral was consecrated.

Also in 1928, the Oecumenical Patriarchate transferred Archbishop Christophoros to his home island of Samos. Father Theophylaktos Papathanasopoulos was appointed Patriarchal Representative. The post of Archbishop was not filled until 1931, with the election of Father Timotheos Evangelinides as the second Metropolitan of Australia and New Zealand. He arrived on 28 January 1932 and served in this post until his election as Metropolitan of the Aegean island of Rhodes in 1947.

Community development

The interwar period was a time of great growth for the Sydney Hellenic community. In 1920, Nikolaos Marinakis took over Australia's first Hellenic-language newspaper, Okeanis (Ocean; founded 1913), and renamed it Ethnikon Vema (National Tribune). Another publication, the Panellenios Keryx (Panhellenic Herald, today the Greek Herald) began publication in 1926.

The first regional associations appeared between the wars. Formed by migrants from particular locales in the Hellenic world, they served multiple purposes, including providing settlement services for new arrivals and a social network. The first one to emerge was the Kytherian Association (1922), identifying with the Ionian island of Kythera (between the Hellenic mainland and Crete). [media]Two years later, the Castellorizian Club (1924) was founded by settlers from the easternmost of the Aegean islands, Megisti (better known as Castellorizo). About the same time, the Ithacan Brotherhood appeared, followed in 1929 by the Cyprus Community of New South Wales.

This foundation of these organisations reveals the patterns of migration and settlement of Hellenes in the Sydney region. That there were enough migrants from these particular islands to form such bodies illustrates the 'chain migration' phenomenon.

The Australian-born generation began to emerge at this time, favouring the professions over business. As noted by the Argus, by the mid-1920s Sydney's Hellenes were 'becoming strong enough numerically to be noticeable as a well-defined section of the community'. [16] George Takhmindzis became the first Australian Hellene to graduate in medicine from the University of Sydney in 1922. Two years later, C Don Service (Servitopoulos) was admitted to practice as a solicitor.

Also in that decade, the first professional diplomatic representative, His Excellency Leonidas Chrysanthopoulos, was despatched from Athens. This was partly a response to Australia's support during the years of conflict in Europe and the genocides in the Near East, as well as to the growing size of the Australian Hellenic community. Mr Chrysanthopoulos established Australia's oldest Hellenic official diplomatic mission, in Sydney in 1926. [17] A series of Honorary Consuls had represented the Hellenic Kingdom between the 1890s and 1926. Most prominent amongst them was Sir Samuel Sydney Cohen, a leader of Sydney's Jewish community, commemorated by the Foundation Stone of the NSW Jewish War Memorial – today, the Sydney Jewish Museum.

The Tavlaridis brothers – Adam and Ioakeim – had migrated from the town of Sarkis in the north-east of the Gallipoli Peninsula between 1905 and 1911. Ioakeim, better known as Mick Adams, became a pioneer in the import of American cafe culture to Australia through [media]his Black-and-White Milk Bars. Drawing on his business success, Adam became a pioneer of the Australian film industry. During the 1920s, he produced a number of films, starring in a few of them himself. One of them, The Boy from the Dardanelles (also released as Daughter of the East), touched upon the genocides of the Hellenes, Armenians and Assyrians, and was partly filmed in the Maroubra sandhills.

The interwar period was a time of great prosperity for the Sydney Hellenic community. As it became more established, it became more diverse. Concentrated in the city's eastern suburbs, community life continued to revolve around the churches and clubs in the suburbs of Surry Hills and Darlinghurst. But World War II brought abrupt, and irreversible, change.

The 'Ten-year War'

After less than a generation of peace, the Hellenic world found itself embroiled in more conflicts. For almost a decade, Hellenes endured invasion and occupation, followed by civil war. These intertwined conflicts left such physical and psychological scars that it is doubtful they will ever fully heal.

The two wars effectively severed communications between Sydney's Hellenes and their families in their towns and villages of origin. In many cases, the separation lasted for years, with one or both parents in Sydney and the rest of the family trapped in Axis-occupied Europe or in rebel-controlled territory in northern Hellas during the Civil War. The situation became even more complicated by the forced removal by the Democratic Army of Hellas (the communist-led rebels) of 28,000 children from the areas under their control. [18]

Australian officials and individuals, including the Australian Council for International Social Services, the Federal Department of Immigration and the Federal Department of External Affairs, played a key role in reuniting many divided families. [19] At the instigation of community groups such as the Hellenic Lyceum of Sydney, an information campaign began, driven in part by the Cold War climate of the time. [20] Federal government correspondence and newspaper reports from mid-1948 to 1952 reflect how widespread and how effective this campaign became. [21] Tens of thousands of dollars were donated to transport abducted children to their parents in Sydney. [22] The first group of 16 abductees arrived aboard a special flight from Belgrade to Sydney, arriving on 14 June 1950. [23] The Stoitis siblings were reunited with their parents at Sydney Airport, the first time the family had been together for 12 years. [24]

The Civil War had another, less obvious, impact on the Hellenic community of Sydney. It added a new ideological perspective to the 'Macedonian Issue', the question of who controlled the geographic region of Macedonia, and its access to the ports of the Aegean Sea.

Migrants from Hellas to Sydney, such as Mihalis Iliopoulos (known today as Mick Veloskey), Stoianis Sarbinis (Stoyan Sarbinoff) and others, established the (Slavo)Macedonian-Australian People's League. During the years of the Civil War, the pages of its publications recounted the horrors of the fratricidal conflict, and carried numerous messages of support from leftist groups such as the Greek Atlas League. For example, the January 1949 edition carried references to a 'Slav Macedonian Congress in Territory of Free Greece', the 'National Liberation Front of Slav Macedonians', 'the anthem of the Slav Macedonian people', and the 'Slav Macedonians fallen for the people'. [25] The hardline position Sarbinis and his colleagues adopted in support of a Slavomacedonian state separate from the Hellenic kingdom alienated many in Sydney who were otherwise sympathetic to the cause of the anti-monarchist rebels. Their openly pro-communist stance also brought the community under the close scrutiny of the Australian intelligence services, as revealed by documents and records now being declassified and coming into the public domain.

The legacy of the Civil War manifested itself in many ways. Unable to make lives for themselves in Hellas, many from the political left came to Sydney in the late 1940s. In the relative freedom of the 'new country', some continued their political activities, becoming involved with groups such as the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales, the Atlas League and the Communist Party of Australia. More than anything else, the Civil War in Hellas cemented the division within the Hellenic community in Sydney between the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese and the Greek Orthodox Community.

Mass migration

Between 1950 and 1973, tens of thousands of Greek migrants settled in the greater Sydney region. The diverse range of travel documents they used in making their way here makes it difficult to precisely determine their numbers; this is however a fairly safe estimate. This was the time of the community's most rapid expansion and development, as a myriad of churches, afternoon schools, athletic [26] and theatrical groups, as well as regional brotherhoods, were created. While some have since disbanded, many are still operating or have merged with others to form larger bodies.

This time of metamorphosis for Sydney's Hellenes as a whole was mirrored in the changes to the Orthodox Church in Sydney. The third Metropolitan of Australia and New Zealand, Theophylaktos Papathanasopoulos, was elected on 22 April 1947. He served until his tragic death in an automobile accident on 2 August 1958. His successor was Bishop Ezekiel Tsoukalas of Nazianzo, Assistant Bishop of the Archdiocese of America. Elected in February 1959, he arrived in Sydney on 27 April. A few months later, the Metropolis of Australia and New Zealand was elevated to the status of Archdiocese, with Sydney as its seat. A distinct Metropolis of New Zealand was created in January 1970, due to the practicalities of ecclesiastical administration.

Archbishop Ezekiel was promoted by the Oecumenical Patriarchate to the Metropolis of Pisidia in August 1974. The Holy Synod elected Metropolitan Stylianos (Harikianakis) of Miletoupolis as the second Archbishop of Australia on 3 February 1975. Following his arrival on 15 April, Archbishop Stylianos was officially enthroned on 26 April. He remains Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia in 2011.

New parishes began forming as Sydney's Hellenic community settled further away from its early roots in the eastern suburbs. The new migrants congregated around inner suburbs such as Redfern, Alexandria and Paddington, largely due to access to public transport and employment opportunities, but later moved further out. [media]Some of the new churches were built by the community, including St Euphemia Bankstown, St Stylianos Gymea and St Paraskevi Blacktown. Churches were also purchased from other religious groups and converted to Orthodox houses of worship. For example, Burwood's St Nektarios, built in the 1800s as a Gothic-style Methodist church, was acquired by the community [media]in 1970. St Sophia and Her Three Daughters church, in Bourke Street near Taylor Square, was purchased from the Presbyterian Church. Sydney's newest parish church, St Therapon Thornleigh, was previously St Luke's Anglican Church.

St Spyridon Kingsford, one of Sydney's largest parishes, is a prime example of the home-grown nature of the expansion of the Orthodox Church in the Harbour City. The foundation meeting was held in the lounge room of the home of George Papanastasiou (Pappas) in the early 1960s. Within a few years, enough funds had been raised for the original church on Gardeners Road. The parish name was selected as one of the major donors was named Spyridon. Fundraising efforts continued and in 1973 the current church (with hall underneath) was inaugurated. The original church building was demolished and the site is currently occupied by the St Spyridon Primary School.

Education

Alongside the parishes, afternoon and Saturday schools sprang up. The migrant generation was keen for its Australian-born offspring to develop fluency in the Hellenic language as well as an understanding of the history and culture of their 'mother' country. There are a number of interesting aspects to this phenomenon. Firstly, the educators had typically completed only secondary education themselves (a major feat in south-eastern Europe until the 1960s). Secondly, the history taught was that of the Hellenic Kingdom. It did not take into account the rich historical experiences of the Hellenes of lands outside the borders of the Hellenic state, such as Cyprus, Constantinople, and the Black Sea littoral. Similarly, the culture cultivated by these community educational institutions was focussed on the music and dance of particular regions within the Hellenic state (especially Peloponnesos, the Aegean Islands, Central Hellas, Epiros and Macedonia). As a result, the dialects that the migrants had brought with them were gradually abandoned by the migrants and largely ignored by their children.

As demonstrated by the recent campaign to include Modern Greek within the Australian Curriculum Languages, education is one of the elements that transcends traditional generational boundaries. Under the leadership of Archbishop Stylianos, four major Orthodox educational institutions were set up in Sydney: St Spyridon College Kingsford and Maroubra (founded 1983), St Euphemia College Bankstown (1989), All Saints' Grammar Belmore (1990) [media]and St Andrew's Greek Orthodox Theological College Redfern (1986). While they have very diverse student and teaching bodies, all retain a focus on the Orthodox traditions and spirituality.

Sydney University teaches Classical Greek in its department of Classics and Ancient History and maintains a department of Modern Greek Studies (the latter being Australia's only one). Macquarie University offers programmes in Classical and Modern Greek language and literature. A Hellenic-language community college functions at AHEPA Hall at Rockdale.

Alongside the three 'day' schools, the community maintains almost 100 individual afternoon and Saturday schools, in addition to state schools that offer Modern Greek as a language study. There also exists a network of daycare centres and preschools with programs designed around the maintenance of Hellenic language and identity. In suburbs as diverse as Earlwood, Bexley North-Kingsgrove, Marrickville-Stanmore, Kingsford, Liverpool, Bankstown, St Marys, Blacktown, Manly, Hornsby and Gymea, there is some form of Hellenic education available.

Regional associations

In a pattern very familiar to Italian and other European migrants, the communal life of Sydney's Hellenes revolved around the church and its affiliate institutions, and the regional brotherhoods. Each brotherhood was constituted by migrants from a particular region, often one particular district. Within these bodies, and through their functions, regional identities continued to be developed. Activities such as dinner-dances, picnics, excursions, theatrical performances and folkloric dance troupes served to maintain distinct regional cultures and dialects so far from their origins.

A 'Hellenic map of Greater Sydney' may be developed by charting the location of community institutions. The most numerous of these (after Archdiocese-affiliated institutions) are the clubs of the regional associations. Concentrated in the St George and Canterbury-Bankstown districts, the bodies in many ways reflect the pattern of settlement of Australian Hellenes in greater Sydney. To cite but a few examples, in Kingsford is the Castellorizian Club; in Rosebery is the Pan-Rhodian Association (from the Aegean island of Rhodes); in Rockdale is the National Headquarters of the Order of AHEPA; in Bexley is the Ilion Association (the district around ancient Olympia in south-western Greece); in Campsie is the Pan-Korinthian Association (Korinth or Corinth, in south-central Greece); in Marrickville is the club of the Pan-Macedonian Brotherhood, 'Alexander the Great'; while in Five Dock are the properties of the Pan-Epirotan Brotherhood (from the Epiros region of north-west Greece) and the Samian Brotherhood of New South Wales (from the eastern Aegean island of Samos).

Of particular interest are the descendants of the survivors of the Hellenic genocide. While thousands of them settled in Sydney over a long period of time, only one group of them, the Pontian Hellenes, formed distinct organisations in the postwar period. Their counterparts from other parts of Anatolia did not follow suit. Considering the difficulties of migrating, settling and establishing in a foreign country, it is quite remarkable that these children of genocide survivors were just as concerned about establishing a cultural presence as an economic one. In 1957–58, the first Pontian group in Sydney was formed, named Xeniteas ('Traveller in Foreign Parts'). Activities focussed on philanthropy, folkloric dance and costume and other cultural traditions. In March 1965 it produced its first theatrical performance, in the Pontian dialect. [27] Like many of the regional brotherhoods formed in the postwar era, the Pontian group went through its share of splits and infighting. There are today three Pontian groups in Sydney: Pontoxeniteas (with premises at 15 Riverview Road, Undercliffe), the Pan-Pontian Brotherhood Panayia Soumela ('Our Lady of Mount Mela', with premises on New Canterbury Road, Hurlstone Park) and the folkloric group Argonauts (based in Sydenham).

These regionally-based organisations – the oldest of which are now approaching their centenaries – played crucial roles in the development of the Sydney Hellenic community. Initially, for recent arrivals they provided access to settlement services such as housing, employment and translators through extended family networks. Over time, they became centres for migrants and their Australian-born children to maintain the cultural traditions unique to their particular island or district. Their role in promoting marriages amongst the children of migrants from the same or neighbouring parts of the Hellenic world was also seen as important. Today, they function largely as locations for retired migrants to gather and reminisce. There are some exceptions, but as the community has transformed into an established one, many organisations are struggling to maintain themselves as separate identities.

Changing patterns of migration

The 1970s were a time of major change for Australia as a whole and for the Sydney Hellenic community in particular. In December 1972, the federal Labor government of Gough Whitlam was elected, bringing in a sweeping range of social and political reform that altered the country forever. Whitlam – still regarded as a hero by many Sydney Hellenes – is remembered by them for introducing the policy of multiculturalism, for openly opposing the military junta that had ruled Hellas since April 1967, and for his government's leading role in condemning the Turkish invasion of Cyprus on 20 July 1974. [28]

The invasion of Cyprus triggered the final wave of large-scale Hellenic migration to Sydney. Thousands of people, made refugees in their own country, found safe haven amongst friends and relatives who had already made the long journey to the Antipodes.

The early 1980s saw two monumental events in Hellas dramatically influence the Sydney Hellenic community. The Hellenic Republic joined the European Economic Community as a full member, and the first socialist government was elected. These twin events initiated an unprecedented period of political and economic stability in Hellas. The prevailing trend of migration was reversed and developed into repatriation of migrants and the emigration of their Australian-born children. Today, Hellas is home to the second largest Australian diaspora community in the world, some 135,000 citizens; only the United Kingdom is home to more Australian citizens.

Politics, culture and sport

The year of Sydney's and Australia's bicentenary, 1988, was a key one for Sydney's Hellenic community. The Hellenic Republic's gift for the bicentenary celebrations was a touring exhibition of antiquities titled Ancient Macedonia: Treasures of Greece. The unique collection of artefacts from the kingdom of King Philip II and his son Alexander III (the Great) was officially opened by President Christos Sartzetakis, the first time a Hellenic Head of State had visited Sydney. The exhibition and the state visit received a rapturous welcome from both migrant and Australian-born Hellenes.

The Ancient Macedonia: Treasures of Greece exhibition was also a trigger for the Macedonian issue to erupt on to the public stage, as the Slavomacedonian community held a series of sometimes violent protests against both the exhibition and the Presidential visit. Later that year, a national football league match between Sydney Olympic and Preston (a Melbourne club backed by the Slavomacedonian community) at St George Stadium erupted into violence, a scene repeated the following year. It was the beginning of one of the darker periods in the history of the Sydney Hellenic community.

The break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1991 gave renewed impetus to the Macedonian issue. In September 1991, the southernmost of the Federation's states declared its independence as the 'Republic of Macedonia'. Efforts by the Slavomacedonian community to have the new country recognised by Canberra under that name were met by intense lobbying and protest rallies by Australia's Hellenes. Police estimated that the 1992 rally in Sydney was the biggest since the Vietnam War, with some 50,000 people taking to the streets of central Sydney.

While Slavomacedonian claims to the name, heritage and lands of Macedonia were not new, they were new to the broader Australian audience, and came at a time of rising xenophobia in Australian society. The violence that accompanied the dispute between communities (such as the attempted firebombing of St Euphemia's church in Bankstown) was met by some commentators with sarcasm and by others with comments referring to 'foreign unrest' which, in the words of then Prime Minister Paul Keating, 'this country could well do without'. [29]

The 1992 'Macedonia is Greek' rally marked the birth of a new phenomenon in the political landscape of the Hellenic community of Sydney – the arrival of the Australian-born as political leaders of the community. This was brought about by a combination of the end of mass migration of Hellenes, migration back to Hellas and Cyprus, and the ageing of the migrant generation. Through the Australian Hellenic Council and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia in particular, Australian-born Hellenes began assuming leadership positions in substantial numbers.

Recent achievements

The early 1990s were a tense time for Sydney's Hellenes, but the later part of the decade was a time of celebration and growth. In November 1996, Sydney hosted the first visit by an Oecumenical Patriarch, His All Holiness Oecumenical Patriarch Vartholomeos (Bartholomew), spiritual leader of the world's 250 million Orthodox faithful.

In 1999 the Archdiocese announced the formation of the Millennium Choir, a specially recruited 200-voice ensemble, to perform at the Opening Ceremony of the 2000 Olympic Games and the Closing Ceremony of the Paralympic Games in Sydney. It was the first time since the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 that the Olympic Hymn had been sung in the original Hellenic. The symbolism was striking: a choir largely of Australian-born Hellenes, singing in Hellenic, in Sydney, in the last Olympic Games of the twentieth century, with the first Olympic Games of the new millennium to be held in Athens, four years later. The names of all the volunteers (including the choir members) are now on display outside the Olympic Stadium at Sydney Olympic Park.

Sydney's Hellenic community has contributed in a myriad of ways since the arrival of the first Hellenes 182 years ago. The streetscapes of Sydney are full of traditional sandstone and modern structures inspired by classical and Orthodox Hellenism. One may find signage in Hellenic in suburbs as diverse as Rockdale, Gymea, Liverpool, Parramatta, Campsie, Gladesville, Crows Nest and Thornleigh. Place names such as Rhodes, Tempe, Greek Street (Glebe), Sydney Olympic Park and many more continue to echo the impact of Hellenism on Sydney.

Hellenic language and history is taught in the city's primary and secondary institutions, while the University of Sydney teaches Greek in its department of Classics and has a department of Modern Greek studies. The University is home to the Nicholson Museum, the southern hemisphere's largest collection of Hellenic antiquities. In 2011 some of the most senior individuals in New South Wales education are Australian Hellenes: Tom Alegounarias (President, New South Wales Board of Studies) and Angelo Gavrielatos (President, Australian Education Union).

In and out of the athletic arena, Sydney's Hellenes make their presence keenly felt: Peter Raskopoulos, Steve Georgakis, and Andy Paschalidis (football), Spiro Zavos (rugby union), John Skandalis, Braith Anasta, Nick Politis and Nick Pappas (rugby league),

In the field of the arts and sciences, eminent Hellenes have included Nick Pappas (Director, Powerhouse Museum), Nick Malaxos (Historic Houses Trust), and Professor Steven Boyages.

In the media and the arts, outstanding Australian Hellenic figures include film director Dr George Miller, actresses Ada Nicodemou, Zoe and Gina Carides,[media] presenters Mary Kostakidis, John Mangos, Michael Tomalaris, virtuoso Niki Vassilakis (the first Girls' Captain of St Andrew's Cathedral School) and so many more.

In the 'bearpit' of politics, Hellenic Sydneysiders have included John Hatzistergos (former Attorney-General of New South Wales, and former Labor member of the Legislative Council), George Souris (former leader, Nationals), Sophie Cotsis (Labor member of the Legislative Council), Jim Samios (Liberal Party), the late Takis Kaldis (Labor Party). These are only a few of a long list of Sydney Hellenes who have been active in politics at all levels.

The roles of women

There is a distinct lack of 'prominent' Hellenic women in Sydney until the narrative reaches the 1990s. This is a reflection of the structure of the Sydney Hellenic community, not of the roles played by women in the development of the community. While the Australian Hellenic community may appear patriarchal, this is very much superficial. At the core of all the community's institutions – churches, schools, regional associations, cultural groups – are the women who dedicated themselves to public service.

There are a number of women's community groups: the Hellenic Lyceum of Sydney, the Greek Young Matrons' Association, the Federation of Greek and Greek-Cypriot Women of Australia (OEGGA). Every ecclesiastical and secular organisation has a 'women's auxiliary' attached to it. From mundane tasks such as cleaning the church after each Divine Liturgy, to preparing meals at fundraising events, to selling raffle tickets, to teaching afternoon and weekend classes, much of the community's infrastructure and activity is due to the efforts of the community's female members.

Some of the more prominent are Mrs Irene Anestis (associated with many groups including the Australian Labor Party, OEGGA, and the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales), Mrs Marina Efthymiou (long-time President of the Hellenic Lyceum of Sydney), and Mrs Dimitra Micos (Greek Welfare Centre of the Archdiocese).

Australian Hellenic women are particularly important as keepers of memory, as the community's historians. Individuals such as Anna Ioannidou (Curator, Greek Australian Historical Archive of the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales, Lakemba), [30] Effy Alexakis and Leonard Janisewski ( Greek Australians: In Their Own Image, Macquarie University), [31] Ouranita Karadimas ( Ithacan Voices, Ithacan Memories) have produced public history exhibitions and publications around the Hellenic experience in the Antipodes.

Patterns of life

The life of parts of the community revolves around the high feast days of the Orthodox Church calendar: Easter, Christmas, the Annunciation, and Dormition of Our Lady. These, along with a number of other feast days important to particular regions, present organisations with the occasions for their commemorative events and festivals.

Easter (celebrated according to the Julian Calendar) is the most important festival, bringing together all sections of the community. Beginning with the 40-day period of Lent, Sydney's 'Hellenic' neighbourhoods such as Marrickville, Earlwood, and Maroubra echo with the sounds of Holy Liturgies as the heavenly scents of incense mingle with that of freshly baked tsourekia and other specialties of the season. The feast culminates with a candlelit celebration of the resurrection that attracts such crowds that major thoroughfares, such as Gardeners Road at Kingsford, are closed to traffic.

An interesting phenomenon has been the development of clusters of Hellenic culture and commerce around Orthodox churches. The Church of the Transfiguration of Our Lord, at Kogarah, for example, has become the focal point for Sydney's most concentrated Hellenic community – estimated at approximately 20 per cent of the local population. In the vicinity of the church, there is the Venus Reception Centre, Alexander's Cafe, a branch of the Cyprus-based Laiki Bank, Yianni's Bakery, Christopher's Cakes and a number of other businesses that cater to the community. Due to the relationship between religious feasts, community events, and personal occasions such as patron saints' name-days, this pattern may be observed throughout Sydney south of the Parramatta River.

March has become known as Greek Festival of Sydney time. A series of events celebrating Hellenic culture are held around Independence Day – 25 March – which is also the feast day of the Annunciation of Our Lady. The focal points of this festival are the Sydney Opera House and Darling Harbour, which become flooded with the music, colour and cuisine of the Hellenes.

Apart from such panhellenic events, special Holy Liturgies, dinner-dances, lectures, concerts abound celebrating historic events and personalities of significance to particular regions: for example, the annual Peloponnesian Festival held in October, dedicated to the southernmost region of mainland Greece. The most remarkable aspect of these festivals is that they are organised and run entirely by volunteers, as are almost all the community organisations.

Australian Hellenic media

As mentioned above, the Hellenic-language media has a long history in Sydney, dating back to World War I. Today, the community is served by three newspapers, a handful of 24-hour radio stations, and a large number of Hellenic-language programmes. Reflecting changes in the media in the broader society, a growing number of websites cater specifically to the community's needs for bilingual communication.

The oldest newspaper in Australia, To Ethnikon Vema (The National Tribune), has passed through a series of owners over the decades. Published as a bilingual monthly, To Vema tes Ekklesias (The Tribune of the Church) is produced by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia with Ikaros Kyriakou as its editor. O Ellenikos Kerykas (The Greek Herald) has likewise had a number of owners. In 2011, Theo Skalkos publishes it Tuesday to Saturday out of Mascot premises, with Michael Mystakidis its long-serving editor. The same group also produces Ellenis , a monthly women's magazine. The bilingual O Kosmos (The World) was first published in 1982. In 2011 it is issued Tuesday to Friday and edited by Georgos Hatzivasilis; among its previous editors was George Messaris.

There have also been a number of short-lived publications including Metropolis, The Monthly Review and others. Initially distributed for free, Metropolis was an English-language weekly magazine produced by the owners of the Enmore Theatre, catering directly to the Australian-born members of the community. In 2011, a new bilingual monthly journal emerged, Alfa Magazine.

Hellenes were prominent in the formation of 2EA, the 1970s forerunner of SBS Radio. [32] In the days before the World Wide Web, this was the main link most migrants had with domestic and international current affairs and sporting results, as well as community news and views. In 2011, announcers at its Artarmon offices are Alex Catharios (Head), Hrisoula Tsambazi, and Themis Kallos. Since the 1990s, a number of private broadcasters have emerged, combining local presenters with broadcasts from Hellas and Cyprus. The most successful of these is 2MM, [33] based in Dulwich Hill. Utilising a blend of local presenters – including Ikaros Kyriakou and Georgos Hatzivasilis – and programmes streamed live from Athens, 2MM has grown a dedicated audience amongst Sydney's Hellenic-speaking community, pioneering talkback radio.

Reflecting the generational shifts facing all traditional media, Sydney's Hellenic-community newspapers are being confronted with the challenges presented by the World Wide Web and other digital media, including satellite television, live radio streaming and news websites. The community no longer relies on newspapers and radio for information. O Kosmos, for example, has developed a website that endeavours to bridge the generational gap. [34]

Present and future

[media]The community's media outlets also provide a glimpse of the future of the community. Younger Australian Hellenes, most of whom have parents from different parts of the Hellenic world or have only one parent of Hellenic descent, either lose all contact with the community or associate with what may be described as 'Pan-Hellenic' organisations, such as the Archdiocese's youth wing, the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales, the Order of AHEPA Australasia, Sydney Olympic and other athletic organisations and similar groups. A number of professional bodies have also emerged such as the Sydney-based Australian Hellenic Educators' Association and the Greek Australian Professionals' Association. [35]

As the migrant generation ages and passes away, a number of secular Hellenic community organisations face dwindling membership and participation. In particular, organisations based around regional affiliations in the Hellenic world (islands, mountain districts and countries other than Hellas and Cyprus) are facing the fact that the Australian-born generations do not place a high priority on involvement. According to the 2006 Australian census, barely 20 per cent of the Australian Hellenic community today is of the migrant generation (55 years and over).

The Australian Hellenic community in Sydney continues to evolve and diversify. It retains an envied vibrancy, with multiple functions on offer most days of the week, year-round: lectures, dinners, dances, rehearsals, athletic contests, and more. As stated at the beginning of the paper, this is only a sweeping overview of the presence and the impact of this group on the Harbour City over the last 182 years.

Notes

[1] A far more comprehensive elaboration of the stories of these and other early settlers can be found in Hugh Gilchrist, Australians and Greeks Volume I: The Early Years, Halstead Press, Sydney, 1992

[2] 'New South Wales: Greek Orthodox Church in Sydney', Brisbane Courier, 30 May 1898, p 5; Hugh Gilchrist, Australians and Greeks Volume I: The Early Years, Halstead Press, Sydney, 1992

[3] 'War in South-Eastern Europe', Brisbane Courier, 29 April 1897, p 5

[4] Argus, 16 February 1916, p 8; 'The Soldiers' Riots', Mercury, 19 February 1916, p 6; 'Our Sydney correspondent: The Soldiers' Riot', Mercury, 19 February 1916, p 11

[5] 'Greeks in New South Wales', Argus, 15 January 1916, p 20

[6] 'Greeks in New South Wales – Sympathies with the Allies', Advertiser, 15 December 1916, p 9

[7] 'Consul-General's New Appointment', Argus, 16 January 1917, p 5

[8] Daily Telegraph, 8 September 1922; 12 September 1922, p 5; 13 September 1922, p 9

[9] J Brown, Turkish Days and Ways, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1940; G Kerr, Lost Anzacs, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1997; LH Luscombe, The Story of Harold Earl, WR Smith and Patterson, Fortitude Valley, Queensland, 1970; TW White, Guests of the Unspeakable, Little Hills Place, Place, 1928

[10] For snapshots of the aftermath of the Hellenic genocide, see 'Starvation in Greece: League of Nations' Appeal', Argus, 29 January 1924, p 8; 'The Refugee Problem', Canberra Times, 17 September 1928, p 2

[11] On 21 June 1916, the Lord Mayor of London wrote to his Sydney counterpart, Richard Denis Meagher. He expressed 'the hope that you might support us by raising funds, in whichever way you consider best'. The approach from London was inspired because 'we have had so many individual donations from your town'. The stated aim of the Fund was 'for the Restoration of the Armenians to their lands, in towns and villages where the Russians have made it feasible and safe'. The British request was declined until after the conclusion of the war, due to the strain the war effort was already placing on existing resources. 'Armenian relief fund – requesting inauguration of', City of Sydney Archives, Town Clerk's Department Correspondence Files, Item Number 3460/16

[12] 'Public Meeting', Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1918

[13] L Wirt, Near East Relief Report, Near East Relief, New York, 1923, p 43. The headquarters of the New South Wales Committee Armenian Relief Fund of Australia became 34 Jamison Street, Sydney. Australia and New Zealand jointly assumed the entire support of one of the largest orphanages in Syria, henceforth known as the Australasian Orphanage. Australia-wide contributions reported during 1922 amounted to approximately US$100,000. Each month the Commonwealth Line of Steamers transported food and other donations from Sydney to Port Said, thence to Syria.

[14] In the second half of 1925, the headquarters of the Australasian Armenian Relief Fund moved from Adelaide to 279 George Street, Sydney. By 1927, the Headquarters of the New South Wales Armenian Relief Fund was at Bathurst House, on the corner of Bathurst and Castlereagh streets, Sydney. It later moved to offices at 2 Hunter Street, Sydney. Four large consignments of clothing and food stuffs were shipped to the Australasian orphanage in 1927 and 1928, in addition to remittances of ₤500. 'Wheat for Macedonia. Australia favoured', Argus, 31 May 1928, p 5. In 1928, the headquarters of the New South Wales Armenian Relief Fund moved to 333 George Street. Needlework from girls' orphanages in Beirut were shipped to Australia and sold at the office here, while Australian railways carried parcels free of charge for those donating to the fund.

[15] 'Greeks arrested. Charges against Archbishop', Argus, 6 February 1926, p 24

[16] (Correspondent) 'Sydney Day By Day', Argus, 26 February 1927, p 34

[17] 'Greek Representation. Full Consulate Established', Argus, 18 May 1926, p 15

[18] 'Queen of Greece appeals for return of abducted children', Canberra Times, 30 December 1949, p 3; P Diamadis et al, A Child's Grief. A Nation's Lament, Stentor Press, Sydney 1995

[19] 'Australia takes lead for return of Greek Children', Canberra Times, 3 January 1950, p 2

[20] Declaration by Lyceum Club of Greek Women (Sydney), forwarded to Prime Minister's Office by the Sydney Lyceum Club 26 August 1948, National Archives of Australia, JB Chifley Personal Papers, Correspondence 'Lo-Lz', M1455/1 417; 'Excitement as Greek children reach airport', Canberra Times, 15 June 1950, p 4

[21] 'In Parliament', Canberra Times, 5 May 1950, p 4; 'Greek children for Australia', Canberra Times, 21 September 1950, p 5; 'Friendship with Greece', Canberra Times, 27 March 1951, p 4

[22] 'Greek community seeks aid to regain children', Canberra Times, 7 January 1950, p 2

[23] 'Refugee widows and children for Australia', Canberra Times, 10 June 1950, p 4

[24] 'Excited Greek Family Reunited', Age, 15 June 1950

[25] 'The Truman Doctrine Brings Death to our People in Aegean Macedonia', Makedonska Iskra, January 1949, p 3

[26] Steve Georgakis, 2000 Sport and the Australian Greek, Standard Publishing House, Sydney, 2000; Steve Georgakis (ed), Back to Olympia: The Olympic Games Across Four Millennia 2000–2004, Joba Press, Sydney, 2004

[27] Tribute of the Pontian Brotherhood 'Pontoxeniteas', special edition, 1989

[28] 'Whitlam speaks up for Cyprus', Age, 24 July 1978, p 12; EG Whitlam, 'Australia and Cyprus', address to commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Turkish invasion, Cyprus Community Club, Stanmore, available from Whitlam Institute website, http://www.whitlam.org/; Peter Londey, Other People's Wars: A History of Australian Peacekeeping, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2004, p 97; Theo Giantsos, 'Gough Whitlam took my breath away ... literally', Neos Kosmos (Melbourne), 15 June 2009, available online at http://www.neoskosmos.com/news/en/node/1479, viewed 6 July 2011

[29] S Mostyn and T Wright, 'Keep violence out, urges PM', Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1994

[30] 'Hellenic Historical and Cultural Centre NSW', Collections Australia Network website, http://www.collectionsaustralia.net/org/1792/about/, viewed 6 July 2011

[31] In Their Own Image Project, Macquarie University Australian History Museum website, http://www.austhistmuseum.mq.edu.au/greek/intro.htm, viewed 6 July 2011

[32] 'Brief History of SBS', Making Multicultural Australia website, http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/doc/sbs_3.pdf, viewed 6 July 2011 ; SBS Greek Program, SBS website, http://www.sbs.com.au/yourlanguage/greek/, viewed 6 July 2011

[33] 2MM o melodikos stathmos (the melodious radio station), website, www.2mm.com.au, viewed 6 July 2011

[34] O Kosmos bilingual Greek-Australian newpaper website, http://60.241.173.43/kosmos/, viewed 6 July 2011

[35] Greek Australian Professionals' Association website, www.gapa.com.au, viewed 6 July 2011

.