The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Americans

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Americans

The 'ties that bind us' is a frequently articulated catchcry of American [1] and Australian politicians and diplomats. Such were the congratulations offered to Prime Minister Julia Gillard by President Barack Obama in 2010, in which he expressed his

personal commitment, and the commitment of the United States, to the enduring alliance between our two nations advances our shared interests and values. [2]

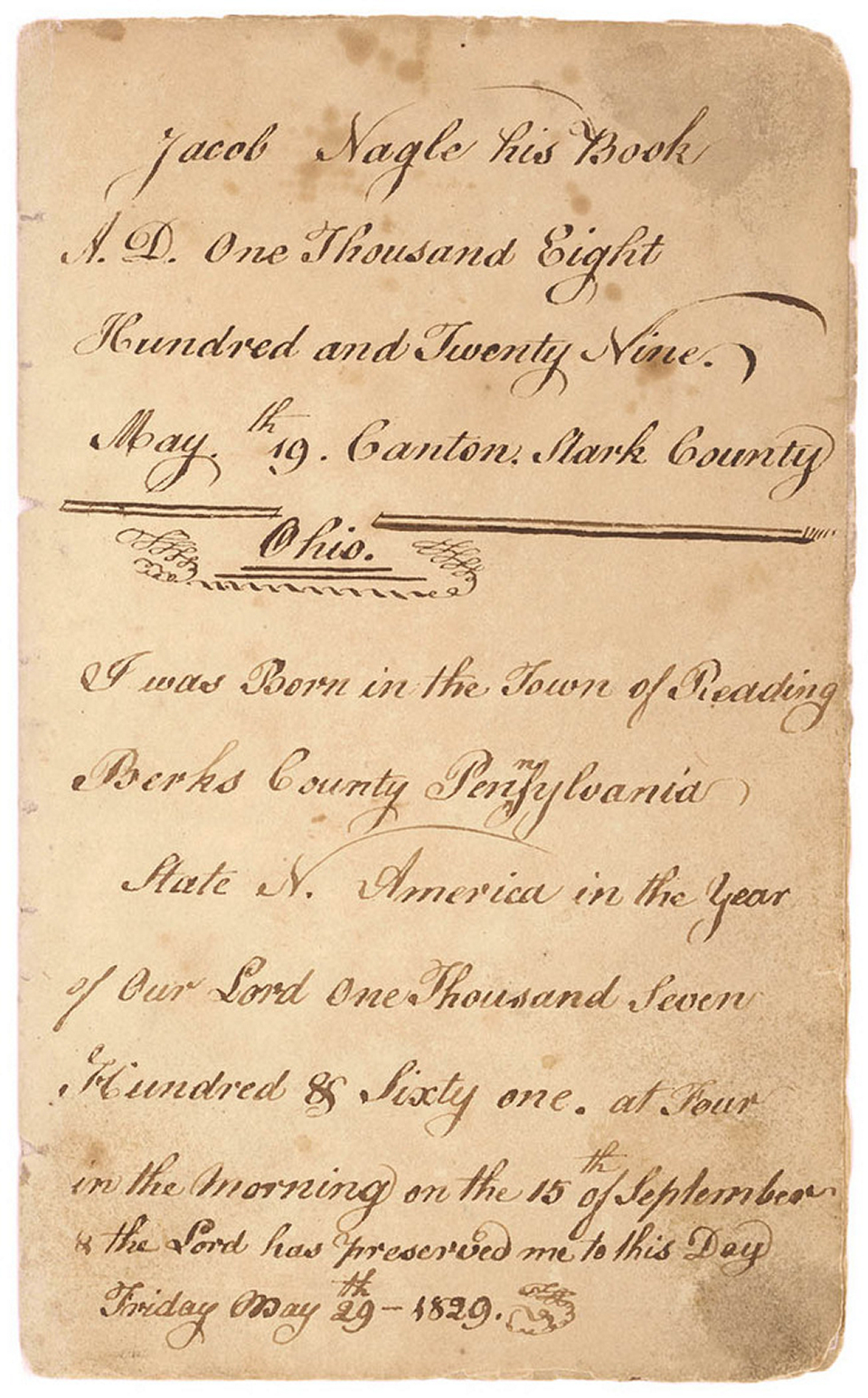

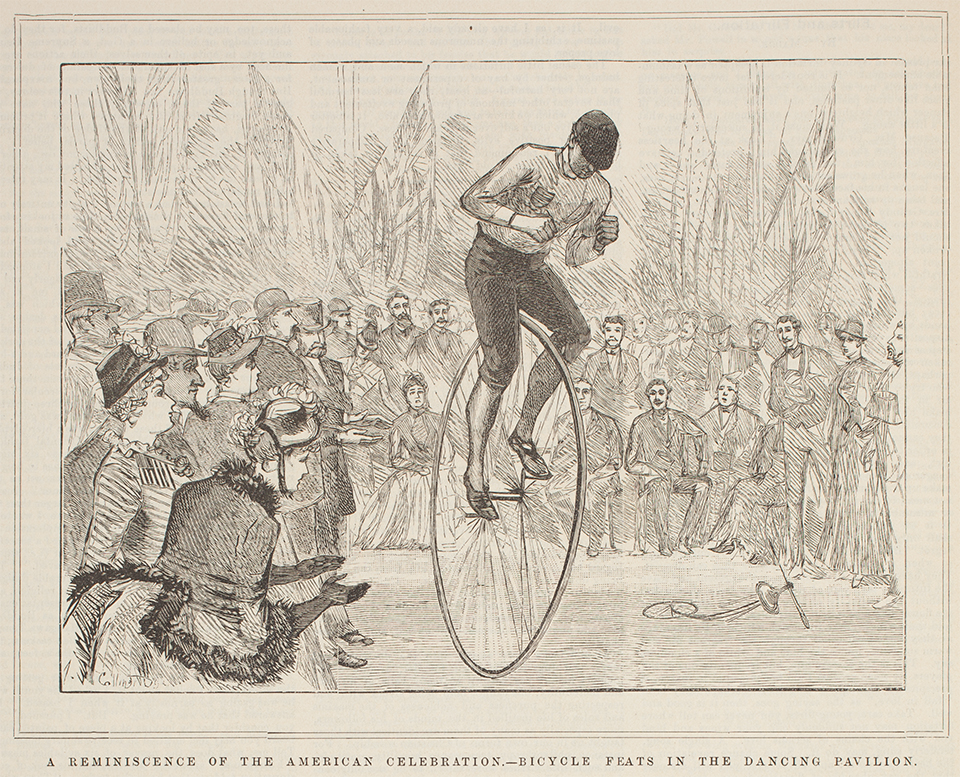

[media]Such ties also stretch as far back as when the first European colonists disembarked upon the shores of Sydney Harbour. The ties reach even further back as one identifies a list of crew on the Endeavour under the command of Lieutenant James Cook during his first Pacific voyage between the years 1768 and 1770. [3] John Thurmond, John Gore and James Mario Matra all originally hailed from what was to become the United States. It was Matra who suggested the possibility of using Botany Bay for a future colony and even foreshadowed that its settlers could include American loyalists displaced by the American War of Independence. [4] When Captain Arthur Phillip led his fleet from Botany Bay to Sydney Cove in late January 1788, John Moseley, a black American, stepped ashore as one of the First Fleet convicts. Billy Blue, of Blues Point fame, [media]recorded his birthplace as New York in his background statement for a petition to Governor Brisbane in 1823. Their stories, along with that of another black American, John Randall, forms part of Sydney's early settlement history. [5]

Whalers, merchant ships and the convict period

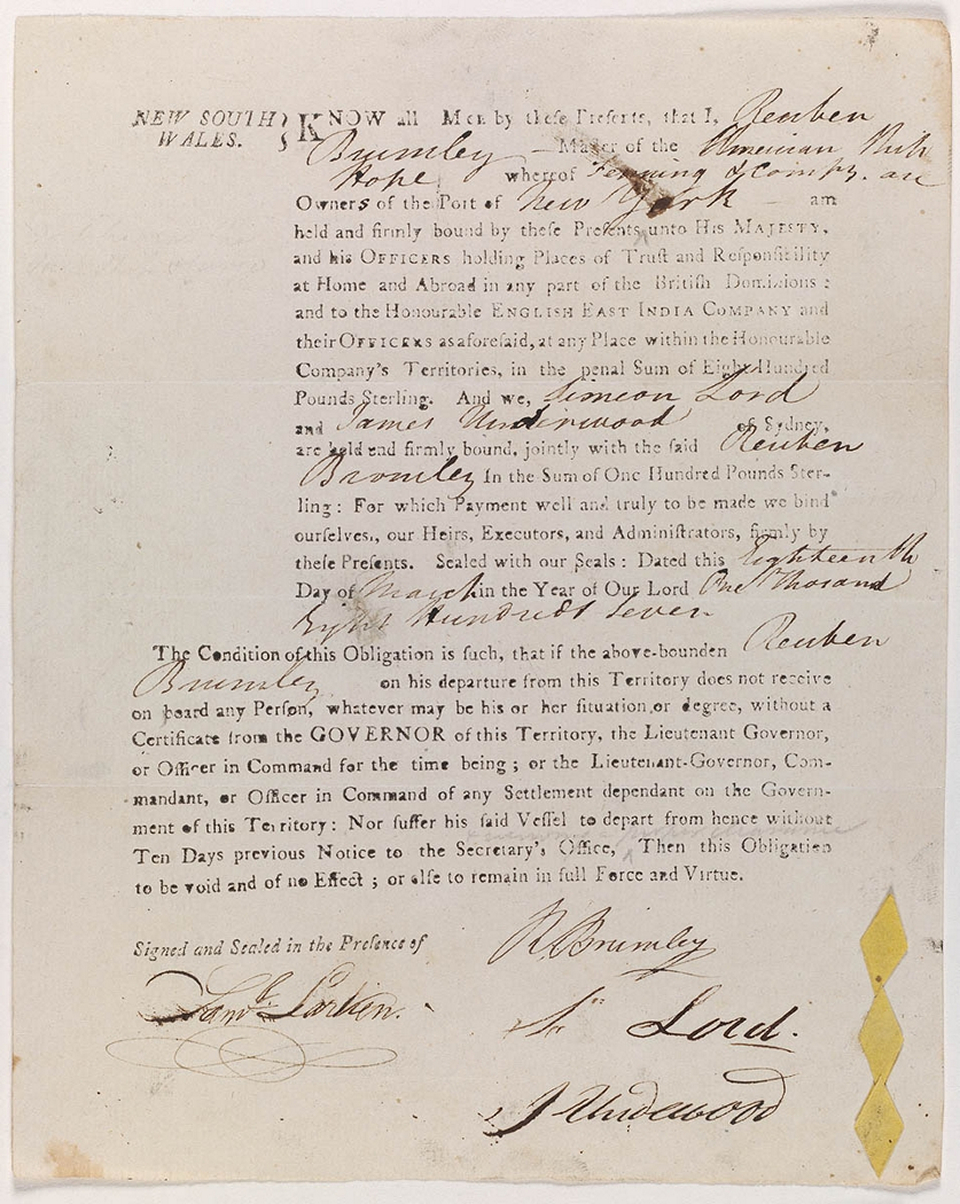

It wasn't long after European settlement that common commercial interests were kindled, with an increasing number of American merchant and whaling ships arriving in Sydney. The fledgling colony of New South Wales, with its secure and magnificent Sydney port, was perceived as a crucial link between the seafaring activities of Americans from the western seaboard and their pursuits in the South Pacific and South America. Although British and French firms engaged in whaling excursions, the Americans predominated, and were seen, at first, as intruders in direct competition with the British colony at Sydney Cove. In 1804 Governor King introduced regulations to restrict visitors and their comings and goings within the vicinity of Port Jackson.[media] Nonetheless the increasing number of American ships and visitors, who often co-opted convicts for their missions to surrounding islands and ports in the first decades of the nineteenth century, demonstrated that King's 'general orders' and attempts to curtail American activities were not successful. This was due, in part, to the lack of British support and the difficulties of communication between the colony and its mother country. Subsequent governors and merchants found the steady arrival of American vessels, loaded with desired goods, more to their liking than a nuisance, and thus trade developed. Convicts inclined to forging an escape route could have viewed the traffic of these ships as a way out to freedom and a life beyond the shackles of the colony. In fact, the Argo and the Otter, both American ships, had been so used. [6] Neutral Bay in Sydney Harbour is so named for this very reason – Governor Phillip had made it the anchoring place for non-British ships, to ensure that foreign ships were 'far enough away'. [7]

Americans were also some of the earliest foreigners to be naturalised. [8] In 1825, Jean Charles Prosper de Mestre was recorded as the second person to be naturalised. Jean de Mestre, considered an American citizen, arrived in Sydney in 1818 and set up business as an importer. Although owning property on the south coast of New South Wales, de Mestre was an influential Sydney businessman and man of property. He sat on the board of directors of the Bank of New South Wales and was instrumental in setting up the Mutual Fire Insurance Company of Sydney. [9]

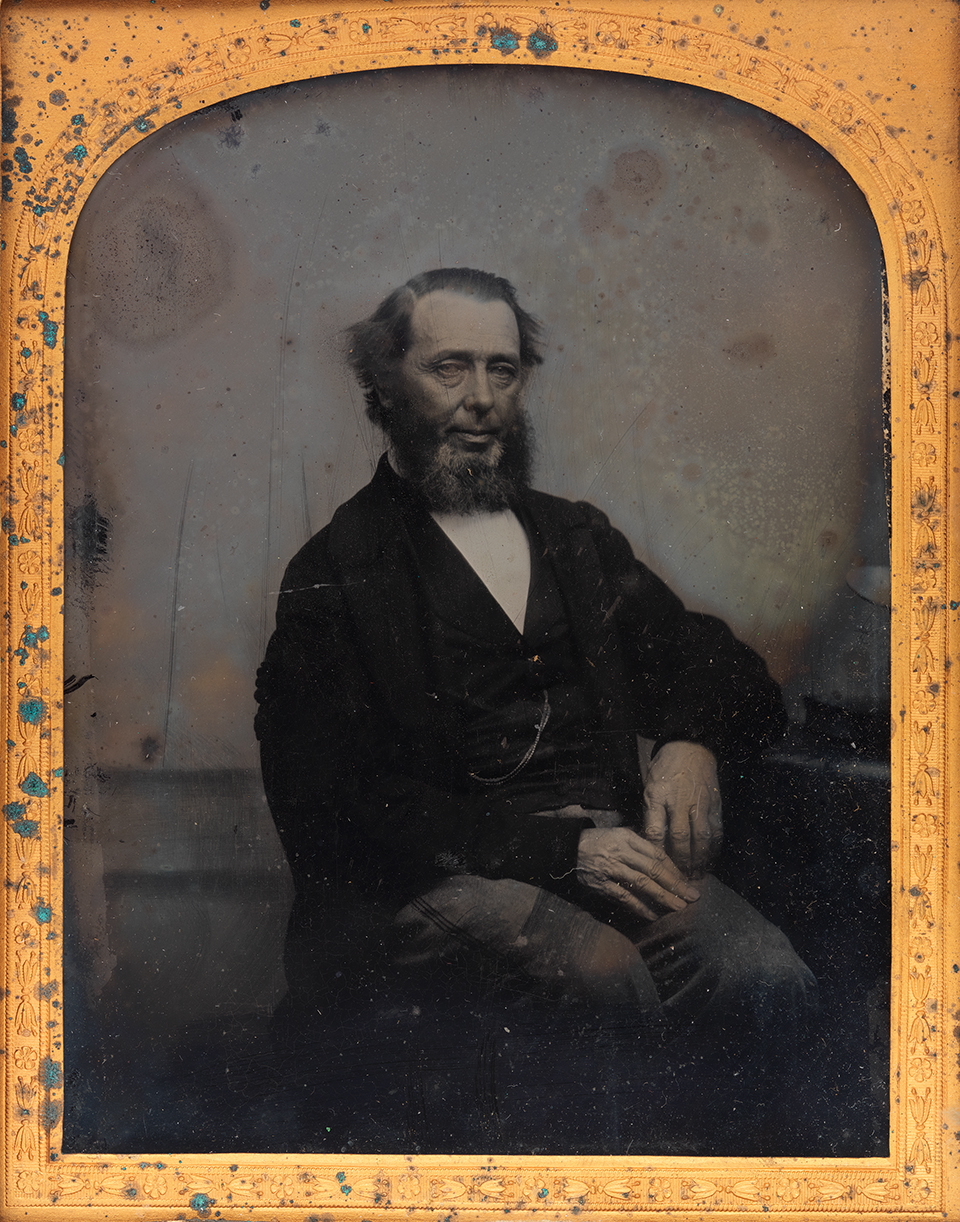

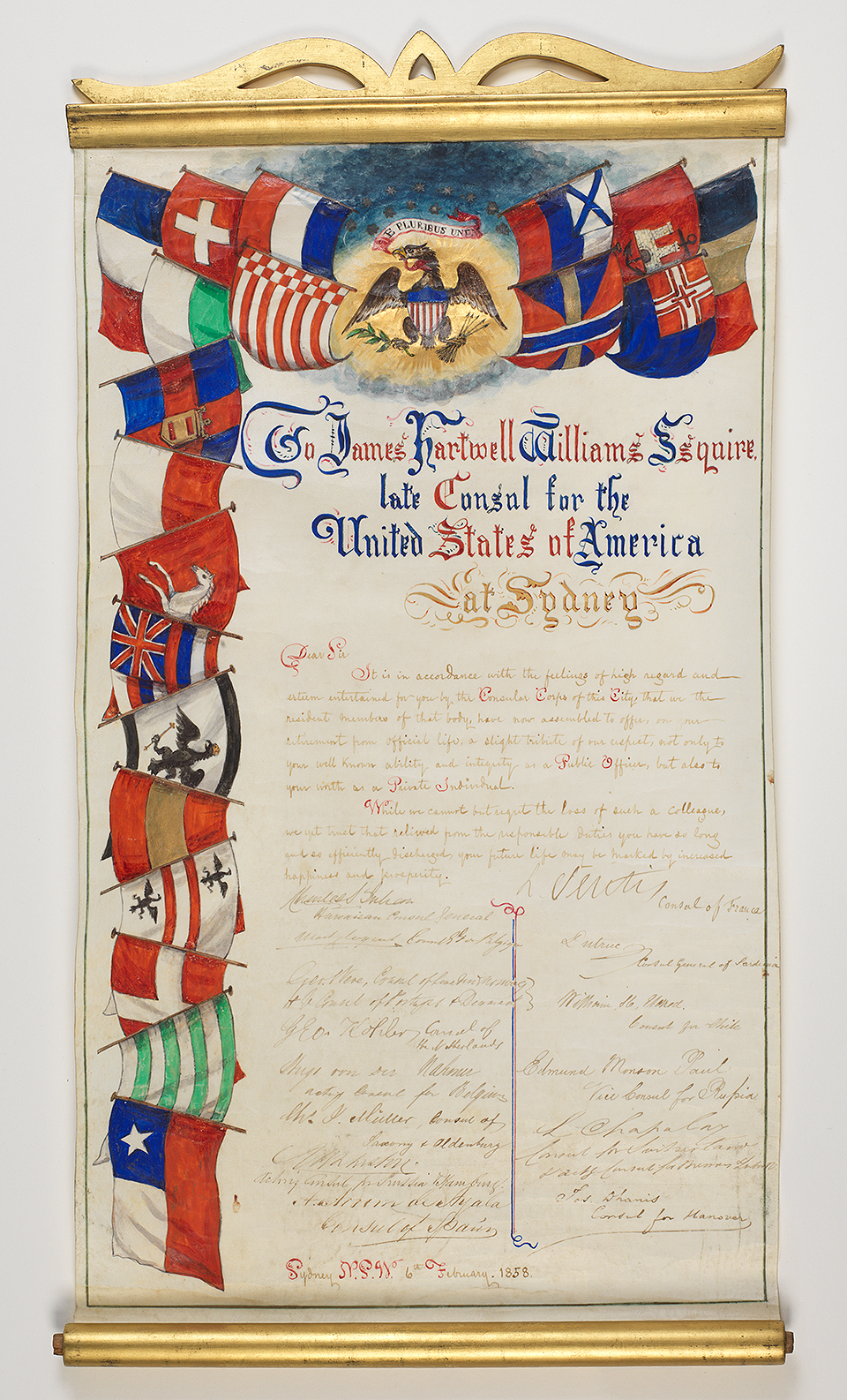

[media]All of these comings and goings by Americans prompted James Hartwell Williams, a merchant himself, to become engaged in diplomacy. Initially Williams acted as a de facto United States consul but eventually convinced his superiors back home to appoint him in an official capacity. Thus anointed in 1836, but not officially gazetted until 1839, Williams set about keeping meticulous records of American business and life via letters, daily diary entries and regular reports back home to the Secretary of State. [10] One of his particular areas of responsibility, apart from keeping stock of his office supplies and the trading business between the colony and the United States, was the protection of American citizens in Sydney Town, and ensuring that these visitors behaved themselves. The Consul saw it as his duty to control his renegade seafarers until such time as a ship was standing by to take them to further ports.

[media]Shipwrecks were commonplace and it also fell upon Williams to extend welfare to his stranded countrymen. Finding them temporary accommodation and a means to earn a living preoccupied much of his correspondence to the US Secretary of State and the Colonial Secretary. In turn, the Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Deas Thomson, approached Williams to share 'some of the more generally important public documents of the United States' on matters of common interest such as public lands and education. [11] Williams married into the de Mestre family and served as the United States Consul, depending on the politics of the day back in America, until 1858. However, his allegiances to Sydney and Australia remained strong and he continued to lead an influential life among the city's rising elite. By the time he established his own trading company, J H Williams & Co, in the early 1870s, he was naturalised. [12]

Gold rushes, enterprises and fortunes

[media]American marine enterprises in the port of Sydney, which included sealing as well as whaling, lasted well into the mid-nineteenth century. By this time the 'rush to gold' had begun. By 1848 gold was discovered in the San Francisco region of California. Not long afterwards, in 1851, Australia's own gold rush was on, although the precious metal had been uncovered years earlier. Keen American goldseekers, many of whom had already ventured to the Californian gold fields seeking their fortunes, embarked upon a voyage downunder to continue their search for gold and glory.

Americans were among the thousands who came through Sydney or Melbourne on their way to the goldfields of New South Wales and Victoria between 1851 and 1856. Taking advantage of the activities and services surrounding a gold mining boom, Americans also sought their fortunes as shopkeepers, coach drivers, lodging providers and food purveyors. As young republicans, many Americans on the goldfields avidly supported a republican fervour among the miners. Several were present during the Eureka Stockade and were not shy about encouraging Australians to march towards republicanism.

Other professions made their mark upon the young nation, which by the mid-nineteenth century had been granted 'responsible' government by its British masters. Some were invited as experts in their fields and lent their business acumen and ingenuity towards large-scale mining projects, infrastructure construction and agricultural advancement. Others came as preachers in the true American evangelical style offering salvation, the truth and the way. As the twentieth century unfolded, an ever-present trading interest, the boom of the insurance business, and the availability of commodities such as electricity, the motor car and refrigeration, all provided increasing commercial links between Australians and Americans. [13]

By the mid-nineteenth century, Sydney was a vibrant and bustling metropolis. The discovery of gold not only brought Americans who were seeking gold, it also offered the many opportunities that flowed from it. While not all were successful in their business activities, their energy and determination was admirable. For example, Hayden Hezekiah Hall, a shipping merchant, arrived in Sydney in the 1850s and dabbled in a variety of business enterprises, mostly via the Hunter River trading steamers. Although he returned to the United States, Hall maintained his interest in Sydney and returned as an official commercial agent in 1866. After he took on the consular title, which was not endorsed by his political masters in Washington, his status declined. Appearing never to give up, Hall endeavoured to run passenger and mail steamers between the United States and Australia as well as New Zealand, constantly seeking backing from anyone and everyone. [14]

We associate Americans in Australia with iconic names such as Cobb & Co – the coach company established by Freeman Cobb during the gold rush years. Its connection to Sydney as a people and goods mover is important, but its founders maintained a Victorian presence, not a Sydney one. It was James Rutherford, also an American, who was responsible for extending the coach business into New South Wales. [15]

Yankee migration and government incentives

[media]While this flow of passage between the United States and Australia flourished from colonial times throughout the nineteenth century, a more formal migration scheme was not established. The New South Wales government sponsored assisted immigration schemes from Ireland in the late 1850s and early 1860s, many of whose migrants travelled to Australia from Ireland via New York. [16] But in 1876, during the period when the American Centennial Exhibition was being held in Philadelphia, the New South Wales government, under Premier Robertson, published new immigration regulations. These expressly named immigrants from the 'eastern portion of the United States' for approval as migrants to New South Wales under the authorisation of an agent of the Colonial Secretary. Funding towards their passage to Australia would be subject to the same arrangements as those prescribed to British immigrants. [17] They had to be of sound and moral fibre, physically fit and able to labour towards a prosperous outcome for the colony of New South Wales.

Roderick William Cameron, a government agent, engaged five ships (known as Cameron's Ships) to carry the first wave of official migrants from the eastern seaboard of the United States. Not all, though, were American-born; many had come from Europe in the few years before the departure of the first of these ships in 1877. Those who arrived at the port of Sydney included specialised labourers to work on farms and in mines, as well as domestic help. Married couples with children, single men and a smaller proportion of single women bravely took this vast sea voyage to a new homeland. It was a short-lived scheme. Pressure from a variety of sources, including from within the government itself, forced its cessation by 1879. By 1878 Sir John Robertson was replaced by Sir Henry Parkes in his third term as Premier. A new set of immigration regulations was proposed and American migration was omitted. [18]

Newspaper commentary during this short period was lively and both for and against the importation of American workers. Referred to in a sarcastic manner as 'our American cousins', they were chided for their 'Yankee' know-how and temptation to be better and more efficient than most. At the same time, the papers reveal fear of the unknown, the mystique of the foreigner and apprehension of job losses to perhaps more willing opponents. This type of criticism was to remain constant in Australian commentary on American influences on the Australian way of life, be it social, economic or cultural, up to the present.

To delve fully into the story of American people and their exploits in Sydney would fill a large tome. I have attempted to provide a taste of the types of Americans who visited, stayed and in some way changed or contributed to the Australian way of life in Sydney. It is not possible in this space to reflect upon American cultural influences in general. What picture theatre in Sydney didn't show American movies or sell popcorn? What record store would be without the crooners, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley? American literature, film, food fads and pop culture have permeated almost every corner of Australian society and culture. Sydney, of course, was no exception, and indeed possibly led the way.

Performers, adventurers and the spectacle

Whether official or not, Americans continued to visit. Artists, writers and adventurers were welcomed with packed houses to hear their stories and see their performances.

[media]Author, humourist and raconteur Mark Twain (Samuel Longhorne Clemens) visited Sydney during his Australasian tour in late 1895. His unique rambling lectures were delivered to large audiences at both the Protestant Hall and the Athenaeum Club where the auditoriums were 'packed to suffocation'. [19] Twain generally discoursed on personal experiences and all things American. But he touched a familiar note with his Australian audiences when he reminisced on 'lawyers and bars, newspaper editors, horse-thieves, and Congressmen' … the guests 'screamed at this thoroughly typical Twainesque linking together of opposites'. [20] Twain is honoured in Sydney in the Writers' Walk along the foreshores of Circular Quay. [21]

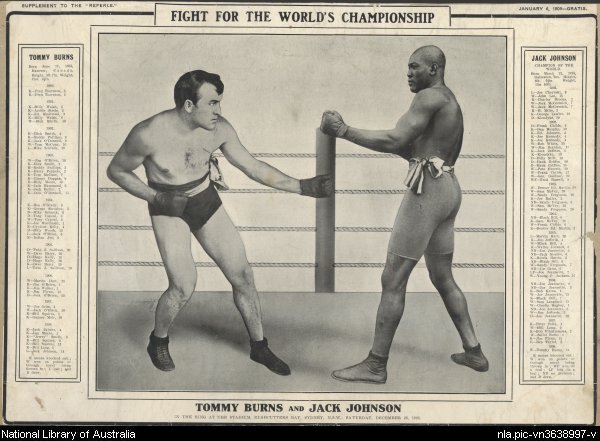

Another well-known American writer, Jack London, adventured to the South Seas and called into the port at Sydney in 1908. Although intending to deliver a lecture or two, he became ill and spent much of his time in Sydney in hospital. However, London managed to attend the world heavyweight boxing championship. [media]At Sydney Stadium on Boxing Day 1908, the black American Jack Johnson fought the Canadian Tommy Burns (called by London the 'Great White Hope'), refereed by the fight's promoter, Hugh D McIntosh. It was not just any fight: fuelled by racism and scaremongering, anticipation and excitement ran high. Hopes were placed on Tommy Burns taking the title, but it was Johnson who won the day. [22]

Earlier in the month, Sydneysiders' attention was drawn to London's yacht Snark. Especially constructed for London's sea voyage, this hardy timber yacht was home to London and his wife during their cruising passage throughout the Pacific Islands. During the course of his voyage from the Klondyke goldfields to Sydney, London wrote several books, one of which focused on his travels in Snark. Like Twain, London has a place in Sydney's Writers' Walk. [23]

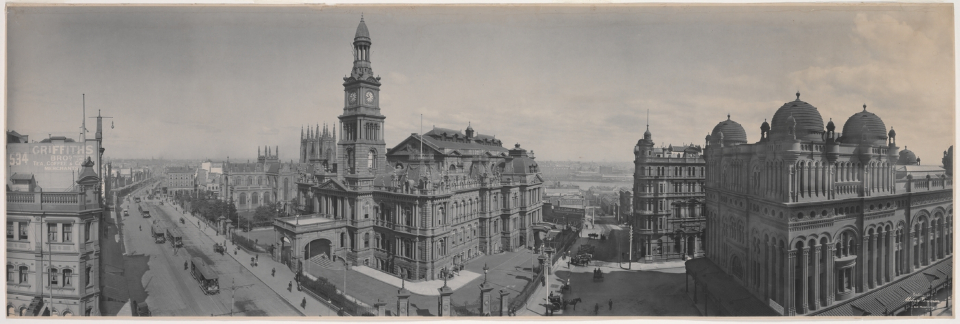

A much [media]larger maritime attraction had brought Sydneysiders out in force to all the prime vantage points of Sydney Harbour earlier that year. On 20 August 1908 the American Naval Fleet entered the harbour. Called affectionately 'The Great White Fleet of our cousins' by the powerful naval supporters of the time at a dinner in honour of the Fleet's arrival, this fleet of warships was then the largest ever seen. A 'thousand guests' feasted at a state banquet held at the Sydney Town Hall on 23 August to celebrate the friendship of the newly federated states of Australia and the United States of America. Guests at the head table, apart from a bust of President Theodore Roosevelt, included the Commander of the American Fleet, Admiral Sperry, the Premier of New South Wales, Mr CG Wade, alongside the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, Governor-General Lord Northcote and New South Wales Governor, Sir Henry Rawson. [24]

Another example of the close ties between the two nations was reiterated that night when Sir Henry Rawson commented that 'Our American cousins and Australians felt that members of the Anglo-Saxon race were all kin. The flags of Great Britain and America were entwined …' [25] The Prime Minister's address that evening, on a slightly different tack, stridently pronounced that although Australia was still an infant 'in a state of tutelage', our Federation was nevertheless a proud nation able to govern itself with 'no need for Australia to pose as a poor relation' if compared to our American 'cousins'. Deakin proffered that, indeed, he looked forward to the time when 'from our harbour should go forth a fleet worthy with that magnificent squadron which had reached the shores of Australia'. [26]

Another American fleet was honoured 78 years later in Sydney Harbour in 1986, when Australia's Navy celebrated its 75th anniversary. This time, the American Naval Fleet, being just one of many foreign visitors, was not entirely greeted with cheers and fanfare. The policy of including nuclear powered warships in its naval force was the subject of citizen protests and outrage around the world. The powerful image of a tiny surfboard hanging on to the bow of USS Oldendorf featured among the organised non-violent anti-nuclear protests common at that time. Ian Cohen, later a Greens member of the state's Legislative Council, was the surfboard rider that day. [27]

[media]Capturing those spectacular moments or special Sydney places was the job of Melvin Vaniman when he came to Sydney in 1903. Growing up in a farming community in Illinois, Vaniman, originally interested in music teaching and practice, developed a love of photography. Attempting to produce the penultimate photographic image – the panorama – was his pursuit. It was his unusual style and method which attracted the attention of the Oceanic Steamship Company. [media]Pursuing ways to foster tourism and encourage paying travellers to venture to Australia and New Zealand on their ships, they contracted Vaniman to produce enticing images. He loved Sydney – certainly his imagery of the city confirms this as does his own words: 'my chief love in this country is Sydney. I am very fond of it; its residents and – of its climate'. [28] Vaniman's Sydney panoramas are among some of the most memorable and eye-catching of the twentieth century, as well as being significant historical documents in their own right.

Sydney's coastal location is perhaps one of its biggest attractions. Zane Grey, another well-known American writer and keen deep-sea fisherman, headquartered at Watsons Bay for a period in January 1939. [29] Three years earlier, Grey's controversial big game fishing tour on the south coast of New South Wales drew a protest from members of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.[30]

[media]American performers on world tours frequently made Sydney one of their major stops. In 1874, under contract to George Coppin,[31] actor and theatre entrepreneur, James Cassius Williamson, an American actor, began his Australian theatrical career. After successful Melbourne and Sydney seasons of Struck Oil, Williamson and his American comedienne [media]wife, Margaret Virginia née Sullivan (Maggie Moore), continued their performing travels but returned to Australia in 1879. They staged HMS Pinafore, in Melbourne then Sydney, after purchasing the rights from WS Gilbert. As a theatrical entrepreneur, Williamson staged one of his more spectacular shows at Sydney's Her Majesty's Theatre in February 1902 – the epic Ben Hur, complete with horses and chariots on stage. [32] Residing in Sydney on and off for nearly 20 years, Williamson formed the company, JC Williamson Ltd in 1910, a name synonymous with Sydney's theatre history.

Williamson gave many other American performers the opportunity to work in Sydney. Some toured, others stayed and made Australia their home. Maud Jeffries was one such star to perform on Melbourne and Sydney stages in the late 1890s and early 1900s, as part of a company tour staged for JC Williamson. Jeffries was a popular actor who made famous the role of Mercia in The Sign of the Cross by Wilson Barrett. [33] Maggie Moore, JC Williamson's first wife, continued to perform in Sydney, sometimes under contract to JC Williamsons Ltd, even after her divorce from Williamson. Her contribution to theatre in Sydney was acknowledged by an extravaganza staged to commemorate her 50 years of performing in Australia. Popular to the end of her career, Maggie lived in Rose Bay before she returned to her Californian home in 1925. [34]

An earlier thespian arrival to Sydney's shores was Joseph Jefferson. Also under contract to George Coppin, Jefferson arrived in Sydney in 1861. An immediate success, his stage repertoire included Rip Van Winkle, Our American Cousin and The Octoroon. Based mainly in Melbourne, Jefferson toured Victorian country towns but made a return visit to Sydney before sailing for London from Melbourne in 1865. [35]

Entrepreneurs, promoters and the professional

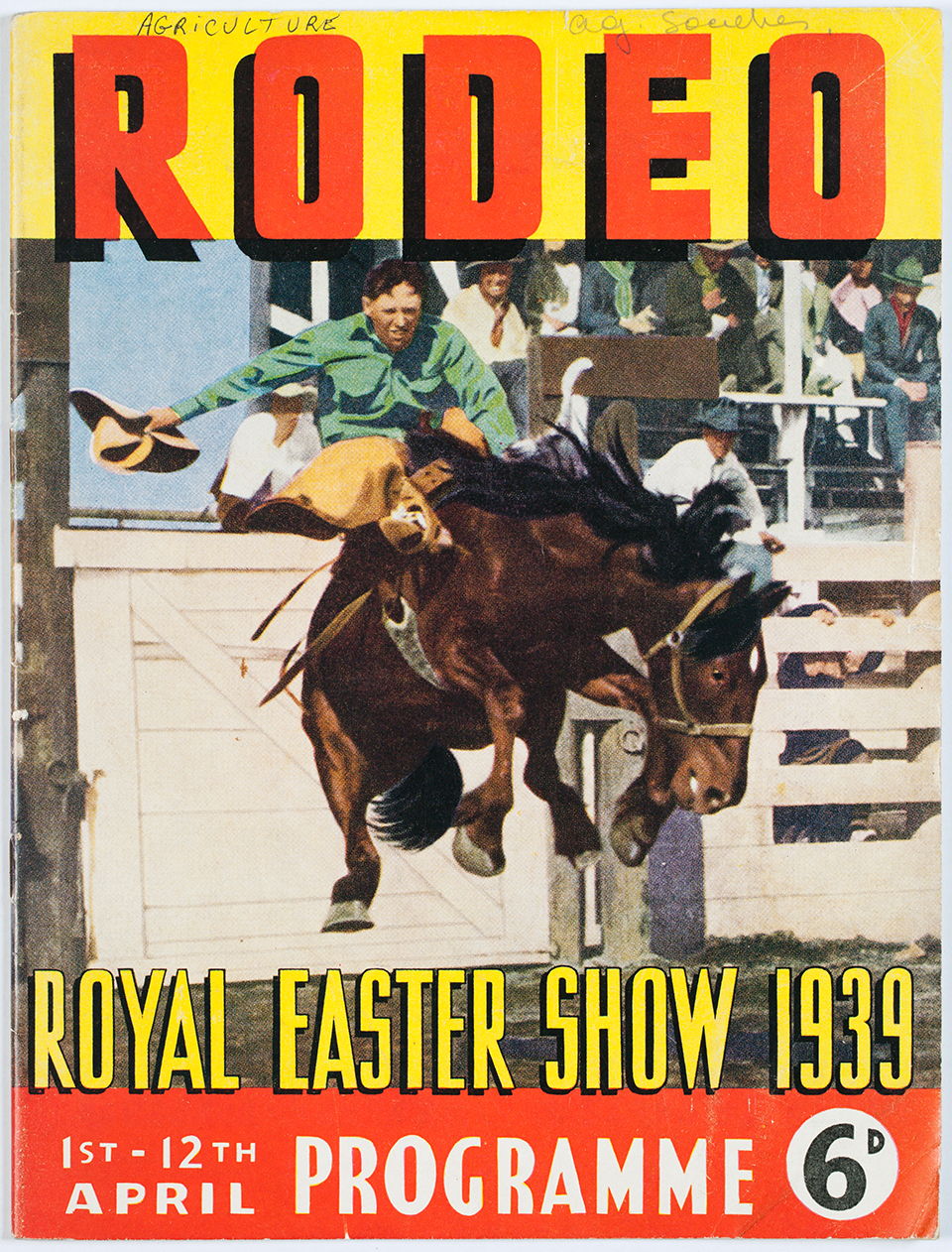

American culture [media]was widely promoted on the world's stage, and Sydney was on the itinerary. Sporting stars, including boxers, sprinters, golfers and even entire baseball teams, flexed their muscles and demonstrated their prowess. On 5 November 1952, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Cleveland Indians began their tour with a match in Sydney before leaving for the other capital cities. [36] The classic American Rodeo show also came to town, complete with cowboys and American Indians. Sydneysiders were presented an opportunity to view this spectacle at the Royal Easter Show in April 1939. [37] This was not the first time though that Sydneysiders had glimpsed native Americans – Sydney's Union Theatres Ltd presented three Sioux Indians in full ceremonial dress as part of one of their theatrical productions in 1928. [38]

Other Americans who stayed in Australia placed their individual stamps on Sydney. Continuing in the theatrical vein, Bob Dyer, a vaudevillian at heart and on the stage, arrived in the late 1930s. With Dyer's repertoire of stunts and sketches and regular guest appearances at the Tivoli, he was soon destined to be a radio star. Dyer's radio quiz show 'Pick-a-Box' made an easy transition to television, and he hosted it, along with his wife Dolly, for 23 years. [39] Radio producer Grace Gibson came to Sydney in the early 1930s to promote the sale of recorded American radio programs. In 1944 Gibson established Grace Gibson Radio Productions Pty Ltd, selling programs to local and interstate radio stations. Gibson used local narrators for her American scripts and was an enthusiastic supporter of the Actors' Benevolent Fund. [40]

Entrepreneur and promoter Lee Gordon was influential in bringing American entertainers to perform at the Sydney Stadium. Gordon, born in Detroit, Michigan, moved to Sydney in the early 1950s. He was quick to grasp the fervour of the rock-n-roll era and began staging tours by singing legends such as Frank Sinatra, Frankie Laine, Johnnie Ray, and Bill Haley and the Comets. Basking in the glory of his 'Big Shows', Gordon expanded his entertainment interests in Sydney and established a Kings Cross discotheque 'The Birdcage', a drive-in restaurant and a striptease club. He was a keen supporter of Australian talent, and Johnny O'Keefe and Col Joye were among those he featured in shows and later his recording label. [41] Other Americans to follow in the footsteps of Gordon and Dyer include entertainer Don Lane and singer Marcia Hines. [42]

Frank Sinatra's visit in 1974 was not as well received as his earlier tour arranged by Gordon. The crooner's off-the-cuff remark about Australian journalists caused him to hide away in his room at the Boulevard Hotel, Kings Cross. A quintessential Australian trade union storm gathered, hotel staff declined to serve him and airline workers joined in seeking an apology. [43]

Controversy and contention appear to always have accompanied Americans in Sydney. This uneasiness with Americans and their character may be traced back to consul Williams and his seafaring renegades. Alfred Deakin expressed his concerns when he urged Australians not to feel the poorer 'cousin' of the two during his speech at the banquet in honour of the United States naval fleet in 1908. Walter Burley Griffin encountered that same 'anti-American' feeling during his Canberra planning period.

Americans from all walks of life have played their part in Sydney's life story. The cartoonist Livingston Hopkins (known as Hop) was born in Bellefontaine, Ohio in 1846, and migrated to Sydney in 1883. His lively work featured in the Bulletin from his arrival in Sydney until his retirement in 1913, caricaturing many a Sydney politician, such as Sir George Dibbs and Sir Henry Parkes. [44] Journalist and activist Jennie Scott Griffiths was born in Texas and, after marriage and work in Fiji, moved to Sydney with her family in 1913. Upon her arrival, she took on the editorship of the Australian Women 's Weekly which gave her the forum to air her feminist and socialist-leaning views. Coinciding with the rise of town planning and social reform, her editorial commentary focused on motherhood education, health and hygiene improvements, and equality for women. By opposing conscription in 1916 she lost her job but continued with her reform work alongside other prominent activists of the day, including Kate Dwyer and Vida Goldstein. [45]

Newspaper editor Lindsay Clinch was born in New York to an Australian father and English mother in 1907. The family returned to Sydney where Clinch was educated at North Sydney Boys' High School. Beginning his newspaper career as a copy boy, he soon was reporting news and eventually became news editor with the Daily Telegraph and Daily News (Sydney). Although Clinch switched his work alliances regularly between the United States and Australia during the 1940s and 1950s, he was employed by John Fairfax & Sons. Defending his right to editorial freedom, Clinch's association with Fairfax presses ended in the mid-1960s. [46]

An American architect won the international competition for the design of Australia's planned national capital in 1912. Walter Burley Griffin's inspiring and monumental designs for Canberra are evident today in the city that grew out of the limestone plains. His wife, Marion Mahoney Griffin, also an architect, was responsible for the dreamy, exquisite drawings which captured the imaginations of the judges and all who saw them. Their work went beyond Canberra and touched both Melbourne and Sydney. In Sydney, the Griffins are synonymous with the Middle Harbour suburb of Castlecrag, where a residential estate was crafted to sit within the bush landscape. Though they only spent four years in Sydney, the Griffins left an indelible mark on the city, not only at Middle Harbour, but also in the presence of distinctive industrial incinerators. [47] Griffin's time overseeing his plans and design work in Canberra was fraught with controversy. Some of this he blamed on anti-American feeling which was prevalent at the time, especially after the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

Frederick Augustus Bolles Peters came to Sydney as a visitor in 1897 and returned two years later to start several manufacturing businesses. Missing his American ice cream, Peters decided to bring this delicacy to Sydney and established a factory at Paddington in 1907. His company, Peters' American Delicacy (later Peters' Ice Cream), branched out into new rooms and additional premises in Sydney eventually spreading interstate. [48]

Associations, wartime and politics

Clubs, associations and societies follow the business trail. The Sydney Rotary Club was formed in Sydney in 1921. This particular brand of club helped to promote business deals, social interaction and knowledge exchange among Americans as well as between Americans and Australians. The establishment of the New South Wales Society for Crippled Children was one of its early achievements. [49] A later president, William Russell Hauslaib, active in the motor and fuel industry, went on to play a part in the Australian-American Association in Sydney and helped to found the American National Club in 1947, later known as the American Club of Sydney. [50] In 1922, five American businessmen lunched together and created the American Society. [51]

American women in Sydney forged an auxiliary group in the late 1930s and were instrumental in organising activities and providing a popular canteen for American troops on leave in Sydney during World War II. After several merges with other American women's interest organisations and societies over the years, the American Women of Sydney, as the group became known, merged with the American Society of Sydney. The first president of the American Women's Club was Eloise Dennett. [52] One of the more illustrious visitors to its canteen during wartime was the American First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt. During her brief Sydney visit in September 1943, Mrs Roosevelt praised the work of the volunteer women at the canteen. Apart from visiting the American forces in Australia and providing wartime encouragement from home, she also took time to visit the Australian women and girls working in munitions factories and other war-related industries. [53]

[media]Relations between Australia and America were not always harmonious. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a standoff developed in relation to imports, exports and other trading issues which resulted in America taking Australia off its 'favoured nation' list. The only other country to be so classified at the time was Nazi Germany. [54] This anomaly in the relationship altered dramatically when the United States entered World War II after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in Hawaii in December 1941. The presence of American servicemen in Sydney was a marked feature of the war on the home front from 1942. As much of the significant fighting occurred in the Coral Sea and Pacific Islands, Sydney was the port of choice for the soldiers', sailors' and marines' R & R (rest and recuperation) leave. [media]The men, in particular, were reported to have their pockets brimming with money. They came for short periods of time to rest up before the inevitable return to the battlefront. About a million servicemen and women disembarked from the ships in Sydney harbour, along with millions of tons of war goods. [55]

City and Kings Cross nightclubs were jammed with Americans. Luna Park on the northern foreshore of the harbour, was the scene for romance and engagement in old-fashioned fairground amusement. Intimate relationships blossomed, many culminating in marriages. Thousands of Australian war brides made the trek across the Pacific to live with their servicemen husbands in the United States after the war. [56] On the other hand, many Americans wanted to stay in Australia after the war ended. This prompted a formal migration program to entice United States veterans to a life in Australia. In the postwar years, Arthur Calwell, the Minister for Immigration, put out a call for 'one million Americans to immigrate'. [57]

From the late 1940s the number of American migrants increased, reaching over 18,000 by 1960.[58] Australian Bureau of Statistics records show that most of these remained in the Sydney region. Perhaps prompted by this success but also seeking American investment and business know-how, the New South Wales government opened a New York office on Fifth Avenue in 1958. Its brief was to 'attract new industries' to the state and to encourage American investment, but it also disseminated information on the benefits of living and working in New South Wales. The office operated for 25 years. [59]

At the same time, a different type of 'investment export' came to Australia. American evangelism had previously arrived on Sydney's shores along with the trading ships, the gold rush diggers and businessmen. But this time, by invitation, an evangelical minister came to conquer. The Reverend Dr Billy Graham began his four-month religious conversion tour in February 1959. Thousands of Sydneysiders turned out to witness the Billy Graham crusade phenomenon, filling the Sydney Cricket Ground, the Showground and Randwick racecourse. Although Reverend Graham subsequently returned to Sydney, his charismatic 1959 crusade made the most impact on Australia's Christian churches. In 2009 a series of events and documentary programs were produced to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the success of Billy Graham's first Australian tour. [60]

A much more practical example of religious exchange took place in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, when Pastor Jim Dykes arrived in Sydney in 1983. After his experiences in San Francisco, Pastor Dykes wanted to provide the type of support network which he helped to establish among that city's gay fraternity. Naming his centre Ankali (from an Aboriginal word meaning 'friend'), he and his team provided counselling and a necessary serve of humanity to the growing numbers of AIDS victims and their families. [61]

Australian and American military ties continued throughout the twentieth century. The enactment of the ANZUS Treaty in 1951 helped to put this alliance on a firmer footing. In the early 1960s, the Australian government made a military commitment towards the American war in Vietnam, although this later became highly controversial. In 1966 the United States President Lyndon B Johnson witnessed the vehemence of protests in Sydney. Angry over the state of the war and Prime Minister's Harold Holt's kowtowing comment 'All the Way with LBJ', thousands of protestors attempted to block the motorcade carrying the President and New South Wales Premier Robin Askin from Sydney airport to the city. Askin's offensive retort of 'Ride over the bastards' only caused further backlash and anguish during this turbulent period. [62]

In 2007, 41 years later, Sydney was the venue for APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation). The presence of President George W Bush at this meeting resulted in barricading Sydney streets for fear of a terrorist attack. Sydneysiders protested in force. [63] Anti-American sentiments were rife and still strong years later.

[media]During the Vietnam War, Sydney was once again the obligatory R & R port for American servicemen and women in between tours of duty. Hundreds of thousands arrived between 1967 and 1971. [64] Not unlike their World War II counterparts, these Americans also frequented Sydney's hot spots and nightlife, and sampled the other sights and sounds of the city. Sydney was a far more cosmopolitan city with a larger and more diverse population than it had been in the 1940s, and this contact again saw relationships develop, marriages follow, and another wave of official migration from the United States to Australia.

Partners, allies and a new wave of migration

The Australian government aimed during the 1970s to open up immigration spots for professional Americans, and to target skills considered desirable for Australian growth and progress. Financial enticements were provided to attract American teachers. [65] This was a controversial step in the American migration story as Australian teachers began to raise concerns about their 'American cousins' taking away their teaching jobs.

Other skilled workers also made their way down under, now mostly on airplanes instead of ships, to find work in Sydney and beyond. Migrant hostels were established throughout New South Wales. Villawood was one of these hostels used between 1946 and 1978 where Americans, alongside British and European migrants, settled into life in the suburbs of Sydney. [66] In 2011, it is Sydney's most infamous migrant detention centre.

The financial inducements for migrants usually included some tax-free status for short working periods, partial travel funding and an initial stay in a migrant hostel until the migrant and family were comfortably located in their own accommodation. The hostel arrangement included living quarters, a shop, recreational areas and meals. In return the migrant was expected to work for at least two years, at which time any financial benefit was considered repaid. Naturalisation was then a possibility. [67]

Following the migration period of the 1970s, studies examined why Americans migrated to Australia, what type of Americans they were, where they chose to reside and why they stayed, or returned to the United States. Some remained because they were disenchanted with the American way of life or had created a new life in Australia. Americans who migrated were likely to be more radical than other Americans. [68] They were also often among the professional and more affluent classes of Sydney, usually living in the inner city areas of the eastern suburbs and lower north shore. Today's growth rate of American migrants is registered at 1 per cent by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, a small but steady figure. In the 2006 Census, 13,136 Americans were identified as Sydney residents and New South Wales has the largest distribution of Americans. [69] Also in 2006, the study of the link between Australia and America was taken to a higher level with the establishment of the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney. The Centre was the initiative of the American Australian Association and its aim is to improve understanding within Australia of the depth and breadth of American life and culture. [70]

Americans and Australians have been partners and allies for over two centuries now. Americans have been visitors, investors, entertainers, allies, residents and citizens with varying degrees of influence and notoriety. The most recent American diplomat to visit, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, continued the 'binding ties' commentary, and expressed her view that America has no better friend than Australia. This is usually followed by an explanation of the similarities between Australians and Americans and the shared bonds, values and friendship that has existed since the first days of the colony of New South Wales.

Today, if Americans think of Australia they probably do so in symbols, and many of these are symbols of Sydney: the Sydney Opera House, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Sydney Harbour and beaches. They would view the city as a significant metropolis in the South Pacific which could perhaps offer a better way of life, not entirely unlike what they experience at home in America. The similarities of a democratic way of government and a capitalist economic base might also be cause for interest and enquiry. But there are differences, and these, once encountered, have a way of separating the two peoples. The differences of language can raise barriers and present difficulties and misunderstandings: the way an American approaches work has also been listed among the differences – 'Americans live to work, Australians work to live'. [71]

It is interesting to note that the majority of American migrants interviewed in Sydney and other cities and regional centres reported that they do not associate or seek to associate with other Americans. One interviewee said that they are possibly the only 'out-group without an in-group'. [72] This is perhaps an example of that unique American descriptive style.

Sydney's most prominent American at present is State politician and former Premier Kristina Keneally. An American hailing from Chicago, Keneally embodies all that we know is constant about Americans – their zeal, their tenacity and their persistence in adversity. [73]

References

Ray Aitchison, Thanks to the Yanks?: the Americans and Australia, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1986

Ray Aitchison, The Americans in Australia, Australian Ethnic Heritage Series, AE Press, Melbourne 1986

American Society of Sydney Newsletter, 2003–2006

Americans in Australia: Impressions of United States Citizens who have lived in the Commonwealth of Australia, AustAmer Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1972

Australian Government, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 Census of Population and Housing, www.abs.gov.au

Australian Government, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Sydney Local Government Area, www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS

Australian Government, Australian Social Trends, June 2010, www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS

Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Community Information Summaries, www.immi.gov.au/publications/statistics/comm-summ/text

Norman Bartlett, Australia and America through 200 years, 1776-1976, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1976

Samuel Baum and Christabel Young, The Exchange of Migrants Between Australia and United States, Australian National University, Canberra, 1989

Congress Research Service, Report for Congress: Australia: Background and US Relations, 8 August 2008

Marguerita Carey, Cameron's Ships: Assisted Immigration from the USA to NSW: a Case Study of 5 immigrant Ships from New York to Sydney, Marguerita Carey Research Services, Burwood, Sydney, 2004

Dennis Cuddy, The Yanks are Coming: American Immigration to Australia, R & E Research Assoc. Inc, San Francisco, California, 1978?

Alan Davies, Vaniman Panorama, exhibition brochure, State Library of New South Wales, 2009

Despatches from US Consuls in Sydney, 1836–1906, microfilm, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library

Janice Larson Gentle, 'American Women Migrants in Sydney', MA Hons thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, 1994

Gordon Greenwood, 'The Contact of American Whalers, Sealers and Adventurers with the New South Wales Settlement' in Royal Australian Historical Society Journal, vol XXIX, part III, 1943, pp133–156

James Jupp (ed), Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1988

David Mosler and Bob Catley, America and Americans in Australia, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 1998

Dennis H Phillips, Ambivalent Allies: Myth and Reality in the Australian-American Relationship, Melbourne, Penguin, 1988

Cassandra Pybus, 'From Chesapeake Bay to Botany Bay' in Robert Dessaix (ed), The Best Australian Essays, Black Inc, 2004

Ray Sherman, Australia for North Americans, Sherman, 1975

Mark Twain, Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1899

Mark Twain, The Wayward Tourist: Mark Twain's Adventures in Australia, (Introduction by Don Watson), Melbourne University Press, 2006

Jeff Wells, Boxing Day: The Fight That Changed the World, HarperSports, Sydney, 1998

Southern Eagle, Journal of the American Society, 1990–2003

Notes

[1] (For this article American refers to North Americans from the United States of America); Congressional Research Service, Bruce Vaughn, Australia: Background and U.S. Relations, updated 8 August 2008

[2] United States Reference Service, U.S. – Australia Relations, Statement by the Press Secretary on the President's Call with Prime Minister Julia Gillard, 7 September 2010, usrsaustralia.state.gov/us-oz/2010/09/07/wh1.html

[3] James Jupp (ed), The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation Its People and Their Origins, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1988

[4] Alan Frost, 'Matra, James Mario (Maria) (1746–1806)', Australian Dictionary of Biography,supplementary vol, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 265–266, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/AS10326b.htm

[5] Cassandra Pybus, 'From Chesapeake Bay to Botany Bay' in Robert Dessaix (ed), The Best Australian Essays, Black Inc, 2004, pp 273–5; Cassandra Pybus, Black Founders: the unknown story of Australia’s first black settlers, University of New South Wales Press, , Sydney, 2006, p 5

[6] Gordon Greenwood, 'The Contact of American Whalers, Sealers and Adventurers with the New South Wales Settlement' in Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, vol XXIX, part III, 1943, pp 138–40

[7] Margaret Park (comp), Naming North Sydney, 2nd edition, North Sydney Council, North Sydney, 1996, p 76

[8] Dennis Laurence Cuddy, The Yanks are Coming: American Migration to Australia, R & E Research Assoc, Inc, San Francisco, 1978?, p 14

[9] G P Walsh, 'de Mestre, Jean Charles Prosper (1789–1844)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 1, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1966, p 305, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A010290b.htm

[10] Despatches from US Consuls in Sydney, 1836–1906, microfilm, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library. The despatches include reports, inventories, letters and other data concerning the daily life of an American Consul in Sydney. Correspondence between the US Secretary of State and the Colony Secretary feature among the records viewed during James Hartwell Williams period as Consul; and Annette Potts; 'Williams, James Hartwell (1809–1881)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 6, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1976, pp 404–05, online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A060437b.htm

[11] Letter from Williams to US Secretary of State, 1 January 1842, Despatches from US Consuls in Sydney, 1836–1906, microfilm, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library

[12] Annette Potts; 'Williams, James Hartwell (1809–1881)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 6, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1976, pp 404–05, online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A060437b.htm

[13] Sam Baum and Christobel Young, The Exchange of Migrants between Australia and United States, Australian National University, Canberra, 1989, pp 4–6; David Mosler and Bob Catley, America and Americans in Australia, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 1998, p 12

[14] Ruth Teale, 'Hall, Hayden Hezekiah (1825–1888+)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 4, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972, pp 323–24, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A040366b.htm

[15] KA Austin, 'Cobb, Freeman (1830–1878)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 432–33, online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030404b.htm

[16] Marguerita Carey, Cameron's Ships: Assisted Immigration From the USA to NSW: A Case Study of Five Immigrant Ships from New York to Sydney, Marguerita Carey Research Services, Burwood, Sydney, 2004, p 3

[17] Marguerita Carey, Cameron's Ships: Assisted Immigration From the USA to NSW: A Case Study of Five Immigrant Ships from New York to Sydney, Marguerita Carey Research Services, Burwood, Sydney, 2004, p 12

[18] Marguerita Carey, Cameron's Ships: Assisted Immigration From the USA to NSW: A Case Study of Five Immigrant Ships from New York to Sydney, Marguerita Carey Research Services, Burwood, Sydney, 2004, p 16

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Sept 1895, p 6 ; The Protestant Hall was located at 236–240 Castlereagh Street and the Athenaeum Club at the corner of Castlereagh and Hosking Streets

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 Sept 1895, p 6

[21] Mark Twain's Australian lecture tour of 1895 is the subject of his book: Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World. Extracts from this work feature in Don Watson's edited The Wayward Tourist: Mark Twain's Adventures in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2006. Watson introduces Twain's storytelling style and provides a brief overview of Twain's life, his lecture style and his Australian journey; http://goaustralia.about.com/od/cultureandthearts/ig/Sydney-Writers-Walk/

[22] Jeff Wells, Boxing Day: The Fight That Changed The World, HarperSports, Sydney, 1998, pp 1–5

[23] http://goaustralia.about.com/od/cultureandthearts/ig/Sydney-Writers-Walk/; The Argus, 12 December 1908, p 20; Sydney Morning Herald, 4 March 1909, p 8

[24] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 August 1908, p 14

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 August 1908, p 14

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 August 1908, p 14

[27] Ian Cohen, New South Wales Greens website, http://nsw.greens.org.au/people/ian-cohen, viewed 20 June 2011

[28] Alan Davies, Vaniman Panorama, exhibition brochure, State Library of New South Wales, 2009

[29] The Argus, 30 January 1939, p 9

[30] Advertiser, 13 February 1936 p 18

[31] Sally O'Neill, 'Coppin, George Selth (1819–1906)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 459–62, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030430b.htm

[32] Helen M van der Poorten, 'Williamson, James Cassius (1845–1913)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 6, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1976, pp 406–07, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A060439b.htm

[33] Diane Langmore, 'Jeffries, Maud Evelyn Craven (1869–1946)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 9, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1983, p 476, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090468b.htm

[34] Richard Refshauge, 'Moore, Maggie (1851–1926)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 5, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1974, pp 279–80, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A050322b.htm

[35] Dennis Shoesmith, 'Jefferson, Joseph (1829–1905)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 4, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A040537b.htm

[36] Canberra Times, 14 July 1952, p 2

[37] The Mercury, 8 April 1939, p 10

[38] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 September 1928, p 8

[39] Diane Collins, 'Dyer, Robert Neal (Bob) (1909–1984), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 17, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2007, pp 348–49, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A170344b.htm; Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 1942, p 7

[40] Lynee Murphy, 'Gibson, Grace Isabel (1905–1989)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 17, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2007, pp 431–32, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A170429b.htm

[41] Michael Sturma, 'Gordon, Lee Lazer (1923–1963)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, pp 298–99, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A140337b.htm

[42] 'Don Lane', Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Lane, viewed 21 June 2011; 'Marcia Hines', Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcia_Hines, viewed 21 June 2011

[43] Shane Maloney, 'Frank Sinatra and Bob Hawke', The Monthly: Australian Politics, Society & Culture, no 50, October 2009, No 50

[44] BG Andrews, 'Hopkins, Livingston York Yourtee (Hop) (1846–1927)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 4, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972, pp 421–22, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A040475b.htm

[45] TH Irving, 'Scott Griffiths, Jennie (1875–1951)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 16, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002, p 199, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A160234b.htm

[46] Valerie Lawson, 'Clinch, Lindsay (1907–1984)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 17, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2007, p 225, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A170222b.htm

[47] Peter Harrison, 'Griffin, Walter Burley (1876–1937)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 9, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1983, pp 107–10, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090111b.htm; The architectural partnership of Griffin & Nicholls (Eric Milton Nicholls worked with Griffin in Melbourne) designed several Sydney incinerators between 1930 and 1936, located at Kuring-gai, Randwick, Glebe, Willoughby, Pyrmont and Leichhardt Walter Burley Griffin Society website, www.griffinsociety.org, viewed 21 June 2011

[48] GP Walsh, 'Peters, Frederick Augustus Bolles (1866–1937)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 11, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, p 208, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A110214b.htm

[49] Paul Ashton, 'Reactions to and Paradoxes of Modernism: The Origins and Spread of Suburbia in 1920s Sydney', PhD thesis, Macquarie University, 2000, pp 212–13

[50] James H Coleman, 'Hauslaib, William Russell (1897–1970)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p 409, online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A140468b.htm

[51] American Society of Sydney Newsletter, May 2003. B Lachlan, RV Cayce, AA Burch, WJ Howatt and AW Boynton initiated the luncheon held to form the Society on 14 November 1922. Cal Loney was elected its first president

[52] American Society of Sydney Newsletter, May 2003

[53] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 September 1943, p 8; American Society of Sydney Newsletter, May 2003

[54] Ray Aitchinson, The Americans in Australia, A E Press, Melbourne, 1986, p 96

[55] Ray Aitchinson, The Americans in Australia, A E Press, Melbourne, 1986, p 98; Department of Veterans' Affairs, 'All in – 'over-sexed, over-paid and over here', Australia's War 1939–1945 website, www.ww2australia.gov.au/allin/yanksdownunder.html, viewed 21 June 2011

[56] Department of Veterans' Affairs, 'All in – 'over-sexed, over-paid and over here', Australia's War 1939–1945 website, www.ww2australia.gov.au/allin/yanksdownunder.html, viewed 21 June 2011

[57] New York Times, 15 August 1947, p 8 in Dennis Laurence Cuddy, The Yanks are coming: American Migration to Australia, R & E Research Assoc, Inc, San Francisco, 1978?, p 18; Southern Eagle (Journal of the American Society), November 1995

[58] Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Community Information Summaries – The United States of American-born Community, c2006, p 1

[59] New South Wales Government Office, New York, Agency Number 5134, State Archives of New South Wales, pp 1–2

[60] Billy Graham Down Under, Compass, ABC TV, 15 February 2009, online at www.abc.net.au/compass/s2484481.htm, viewed 21 June 2011

[61] Ray Aitchinson, The Americans in Australia, A E Press, Melbourne, 1986, p10 ; Jim Dykes interviewed by Martyn Goddard, National Library of Australia Australian Response to Aids Oral History Project, 1992

[62] 'Ride over the Bastards!' in Green Left Weekly, 1 October, 2003, p 1, online at http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/28937, viewed 21 June 2011

[63] Daily Telegraph, 4 September 2007

[64] Ray Aitchinson, The Americans in Australia, A E Press, Melbourne, 1986, p 99; Southern Eagle November 1995

[65] Dennis Laurence Cuddy, The Yanks are coming: American Migration to Australia, R & E Research Assoc, Inc, San Francisco, 1978?, p 75

[66] National Archives of Australia, Fact Sheet 170 – Migrant Hostels in New South Wales, 1946–78 www.naa.gov.au/about-us/publications/fact-sheets/fs170.aspx, viewed 21 June 2011

[67] Author's personal experience as an American migrant in Sydney – arrived on a BOAC flight from New York City into Sydney's Kingsford Smith Airport in July 1971, lived at Villawood Hostel until October 1971; became an Australian citizen in 1996; lived in Sydney until 2003

[68] Janice Larson Gentle, 'American Women Migrants in Sydney: Similarity and Difference', MA Hons thesis, Macquarie University, 1994, pp 95–118. Gentle's thesis provides an analytical view of the differences between Australians and Americans alongside the similarities. Her significant findings include: people from the United States 'arrive with a false sense of security because of the same language, same peoples, same backgrounds, but 'live in another land' or reality'; 'Americans live to work; Australians work to live; 'humour, attitude to work, behaviour, dominance in Australia of male chauvinism'; 'no physical American community'

[69] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 Census of Population and Housing, Sydney, Ancestry by country of birth of parents – United States

[70] History, Mission & Vision, United States Studies Centre website, http://ussc.edu.au/about/history, viewed 21 June 2011

[71] Janice Larson Gentle, 'American Women Migrants in Sydney: Similarity and Difference', MA Hons thesis, Macquarie University, 1994, p 133

[72] Janice Larson Gentle, 'American Women Migrants in Sydney: Similarity and Difference', MA Hons thesis, Macquarie University, 1994, p 202

[73] Kristina Keneally Bio, New South Wales Labor website, http://www.nswalp.com/people/electorate-search/kristina-keneally/ , viewed 21 June 2011

.