The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Christian church architecture

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Christian church architecture in Sydney

Sydney has many buildings set apart by Christians as places of public worship. Their architecture has at times been the most significant in the era, and exceptional in the architecture of Sydney. At other times, church denominations have settled on continuing a successful type, seeking to make a noticeable character across the region. Sometimes the churches seem to be building little of note. Lately the power of the established types has been seen as something to be avoided and very different concepts have been trialled. This overview makes an account of this, identifying the denominations or branches which commission the architecture. Church-building reflects the changing strengths in the denominations at different times, and so the account is sometimes patchy.

The background is Sydney as a great migrant city. Its migrants have necessarily imported its architecture with a view to transporting the culture of the old country. In Sydney there was experimentation with these traditions from the start. The adaptation to the new place began with materials, such as the great sandstone of Sydney, and then moved to siting for effect in the setting, and the adoption of Australian themes in decoration. More recently, the appropriation of salvaged buildings has become important.

This is also an account of what exists in Sydney by way of church architecture and where to find it. There are too many churches for them all to be mentioned, but readers are encouraged to seek them out.

Sydney's earliest churches

Christian church architecture began here with two churches of innovative plan. The first church in Australia was built of primitive materials in just eight weeks by Reverend Richard Johnson. He was the Church of England chaplain to the colony at Sydney and paid for the work himself. Divine service was first conducted in the unnamed church on 25 August 1793. His church had a novel plan, with a three-part chamber in the shape of a T, separating three classes of people, one class being convicts. The governor's rule of compulsory church attendance for the convicts was unpopular and the building was burned down in October 1798. The [media]colonial government responded by lending a storehouse for worship and then starting construction of St Philip's, at Church Hill. This had a novel round tower, possibly for reasons of strength, and another architectural pretension in a domed apse. It was built of stone and dedicated for use in 1810, but was replaced by a new stone church in 1855.

The earliest church still existing is the Union Church at Ebenezer, built in 1809. It was built independent of government or the established church by a union of Protestant settlers. It later became a Presbyterian church, and in 1977 a Uniting [media]church. Its design is more conventional, much like nonconformist chapels in Britain. It has one chamber which served pragmatically as both chapel and school. It is plain and sensible, having the symmetry, good proportions, and solid construction typical of better colonial Georgian buildings. Its original entry door was axially aligned to a great eucalypt, under which the settlers held their first service in 1803. The tree also survives in 2010.

A decade later the colonial government began to build churches. These new churches were architecturally ambitious, to serve the civilising vision of Governor Lachlan Macquarie. Not surprisingly, he looked to contemporary English practice for guidance. He had a trained architect, Francis Greenway, who had been articled under the famed English architect John Nash. Greenway and Macquarie transported to Australia the early eighteenth century preaching room model which was then widely in use for new churches in Britain. In the churches of St Matthew's at Windsor, St James's in Sydney, and St Luke's at Liverpool, they built the earliest serious works of neoclassical architecture in Australia, inspired by the style of John Nash.

In Australian architecture, [media]patterns came to be used frequently, and this is true of Greenway's churches. As well as being beautiful and accomplished, they are important as foundation works of a type. This type might be called the evangelical, consisting of large single chambers with side entrances and usually western towers (the most common tower location found in England). This model was used later for other Anglican churches, including St Peter's Richmond, St Peter's Campbelltown, St Bartholomew's Prospect and Heber Chapel, Cobbitty. Although simple, these churches have been long admired for their stylish architecture, clear form, and dignity of proportion, like their prototype.

These churches were followed by an unsurpassed high period of church architecture arising from the government's policy of part patronage. The Church Act 1836 recognised and part-funded all the main Christian denominations and Judaism. This coincided with a burgeoning colony, the emancipation of the Roman Catholic church, and that great cultural movement in England, the Gothic revival.

Over about 60 years (1836–1890s) Sydney gained a large number of its city, suburban and country churches. They are all substantially built, often elaborate, and several are of brilliant design. They are found spread out across the Cumberland Plain which is today the greater Sydney region.

The Gothic revival in Sydney

In England the revivers of Gothic architecture for churches undertook measured study and comparison of medieval work. The first such 'archaeologically correct' Gothic church to be completed in the colony was St John the Evangelist at Camden, built in 1844. It was probably designed in England by Edward Blore under instructions from the Macarthur family. At the same time the town of Camden was laid out around it. The steeple of St John's is sited to be seen from Camden Park, the house of its main benefactor, and from Wivenhoe, the house of another benefactor. In its architectural innovation and picturesque placement in a controlled landscape, it is among the most important parish churches in Australia.

Sydney [media]has a few churches by other significant English architects of the Gothic Revival, but most are by English architects with wholly or substantially Australian careers. Edmund Blacket was the leading colonial architect of churches. Sydney is loaded with his beautifully controlled, delicate, and distinctly English parish churches. Blacket arrived in Sydney late in 1842 with a folio of his own measured drawings from England. His pursuit of an authentic medieval church architecture was further encouraged by his first clients, Bishop WG Broughton and the Tractarian Canon WH Walsh. Blacket designed a cathedral, major city churches, and a [media]suite of parish churches adapted for colonial circumstances. His work ranged in scale from very small nave churches with one door to large parish churches with transepts, towers, and shallow chancels. Each was a special design and usually executed in stone. The most representative and intact are All Saints Canterbury, St Thomas's Narellan, St John's Darlinghurst; St Stephen's Newtown and the second-generation St Philip's on Church Hill.

The first Roman Catholic Bishop, John Bede Polding (episcopacy 1834–77), also had a suite of standard [media]plans for Catholic churches. His were prepared in England by the leader of the Gothic revival movement, AWN Pugin. While none of the churches survives intact, the hall for teaching at St Mary's Cathedral does. This pure, English hall with huge, mullioned, tracery windows reveals in a small way the principles that made Pugin among the most influential architects of his time.

The earliest large Roman Catholic work to survive is the Villa Maria Monastery, commenced in 1857 at Tarban Creek (now Gladesville). William Weaver's intelligent layout of simple stone buildings is crowned by the extraordinary Church of the Holy Name of Mary. Surprisingly, this is a complete work of French Gothic architecture. It was designed within the Marist order and is said to be derived from the main church in Toulouse.

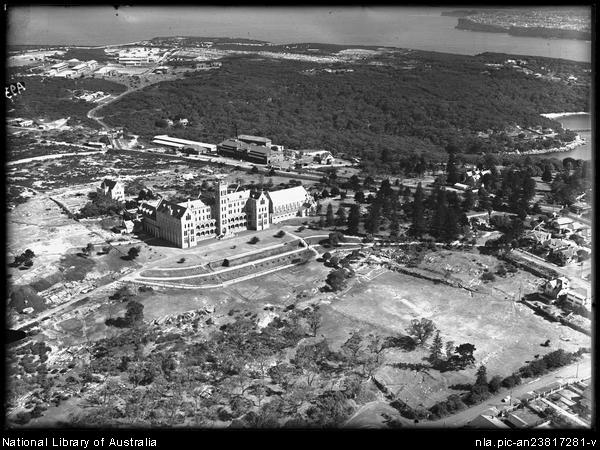

Bishop Polding was [media]succeeded by the Irish-born Francis Patrick Moran, who possessed the vision and energy of a church expanding internationally on a vast scale. His reign (1884–1911) saw dozens of Gothic buildings completed or near-completed. The architectural practice commenced by JF Hennessey was responsible for a great amount, as Moran required the full complement of church institutions. Chief among them is St Patrick's Estate, commenced in 1885 and laid out on raised, isolated land commanding the ocean and harbour at Manly. It contained a great seminary and Episcopal residence complete with pleasure gardens and its own wharf. It is one of the most elaborate and complete landscape and architectural visions in Australia. The monastery for the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart order at Kensington (1895–97) and St Joseph's College for the Marist Brothers at Hunters Hill (1882) are equally grand. The Mission House for the Order of St Vincent at Ashfield (1892) has a double-storey verandah on four sides for use in the same way as a cloister.

For [media]size and Victorian monumentality, the major work of the Gothic revival is St Mary's Cathedral (1868–82). Pugin's close friend and fellow convert William Wardell was a brilliant creator of monumental decorative work who designed both St Mary's and Melbourne's St Patrick's Cathedral. The early stages of St Mary's were built in his lifetime. Hennessey & Hennessey completed all but the spires: however some of the subtle geometry of Wardell's plan got straightened out along the way.

The [media]smaller denominations each built at least one major work of city architecture. The Baptist Chapel in Bathurst Street (1835) by John Verge and the Wesleyan Centenary Chapel (1840) by Josiah Atwool are both in the Greek revival style. John Bibb's Pitt Street Congregational church (1841) was daringly enlarged by George Allen Mansfield in 1868.

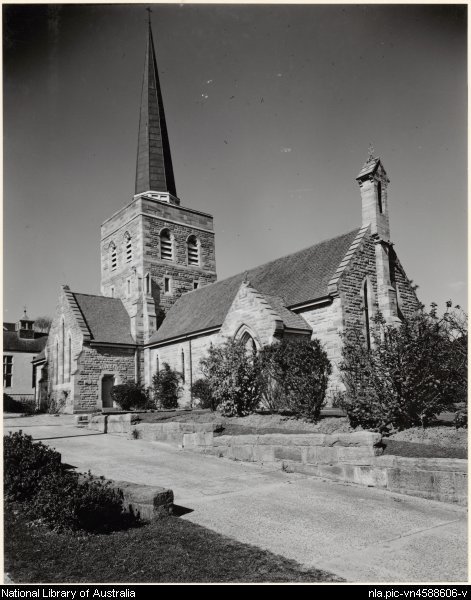

Examples of other [media]excellent churches are Blacket Brothers' Hunter Baillie Memorial Presbyterian church, Annandale, with its sublimely slender spire built of white stone; the excellent conservative Greek revival Bourke Street Congregational church by John Bibb (1846–47); the highly intact St George's Free Presbyterian Church, Castlereagh Street (Rowe & Field 1857); and some beautiful Congregational churches, such as Balmain Congregational Church (1854–55) by Goold & Field, with its great cabinetwork. John Horbury Hunt's Sacred Heart Convent in Rose Bay was built late in the period. It is a high point in the career of the most acclaimed and ambitious architect in New South Wales in the nineteenth century.

Early twentieth-century Italianate

Cardinal Moran, who [media]greatly influenced the high period of Sydney's Gothic revival architecture, was trained in Rome. Eventually he moved away from Gothic architecture and commissioned a revival of Italian architecture that was to characterise the first half of the twentieth century. The parish church of St Vincent in Ashfield (1895–1907) is in the Italian manner, modelled on Renaissance architecture contemporary to the foundation of the mission. The style is carried through in every detail of the interior: the elaborate Carrara marble sanctuary, reredos, altar, and statues, and the huge paintings depicting the stations of the cross. Thereafter the Italian form became normal for extensive Roman Catholic work until the 1950s.

Catholic churches of the early twentieth century are of a consistent and usually modest appearance. The most architecturally accomplished of them are those by Joseph Fowell, partner in Fowell & McConnel (later Fowell Jarvis Mansfield & McLurcan after World War II). St Anne's Shrine, North Bondi, won the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Medal in 1934. It is beautifully executed in every detail from its correct Italian porch in stone to its communion rails. It is also quite original in its treatment and detailing of cavity brick and its innovative ventilation system.

Modernism in church design

Many churches were built in Sydney in the twentieth century: however, more ambitious designs were reserved for new denominations, new types of churches, or for special reasons.

The City Beautiful movement that carved new form into the city immediately after 1900 led to some adventurous city church schemes. The Church of England diocese engaged Professor Leslie Wilkinson and turned St Andrew's Cathedral around to be entered directly from George Street. The cathedral cut down the pew ends, elaborated the chancel with exquisite joinery screens, added an exquisite screen to the north transept and commissioned clerestory stained glass with Australian themes.

The colonial Presbyterian Scots church of 1824 was [media]demolished in 1929 for an integrated city church and offices by Rosenthal, Rutledge & Beattie. It was to be a Gothic skyscraper and was eventually completed to a modern steel and glass design by Tonkin Zulhaika & Greer only in 2006. In 1935 St Stephen's Presbyterian church in Phillip Street was demolished to make way for Martin Place. Its replacement was built in Macquarie Street to the Gothic-style design of John Reid and Finlay Munro.

In the nineteenth century, non-conformist denominations met in meeting halls with sloping floors and a central dais, precursors to the modern auditorium. In 1927 Sydney received its first modern auditorium for meetings of the First Church of Christ Scientist in Liverpool Street, designed by SG Thorp. Externally it is a conservative study in Beaux-Arts classicism. Inside it contains a huge auditorium of fixed arcs of seating on a raking floor. Big churches have continued to be built on this model, including the Wesley Conference Centre in Pitt Street (Hely & Horne, Stuart & Perry 1983), and recently the Hillsong Church (Noel Bell Ridley Smith & Partners, 2007) in Baulkham Hills.

In [media]the twentieth century, architectural commissions for churches ceased to lead architecture as they had in the nineteenth century. There are smaller churches of good quality, but also many built on established plans which vary merely in the application of current general architectural styles. The Anglican churches of the early twentieth century followed the Arts & Crafts movement and among the best are [media]school chapels. The most forward-looking for its time is the chapel of the Sydney Church of England Grammar School (Shore) (JB Clamp and W Burley Griffin, 1913). Wilkinson designed lovely churches and alterations to churches with an air of the English perpendicular Gothic. The most complete was his Sulman-prize-winning St Michael's Vaucluse (1930). Of the many Roman Catholic chapels for schools and convents, the most accomplished is the Cardinal Cerretti Memorial Chapel (1935) which boldly added to Moran's vision at Manly.

Postwar churches

As with most Sydney architecture, the uptake of European twentieth-century modernism was slow. The first modern place of worship was not for Christians – it was the Dudok-inspired Temple Emanuel in Queen Street, Woollahra (1938–41), by the brilliant Samuel Lipson. Modernism broke in more after World War II and some adventurous churches were built in the 1960s. The most striking in conception are those of Stan Smith, whose small Presbyterian churches accord closely with contemporary liturgical innovations found in Europe.

The Roman Catholic Church [media]built many large parish churches on interesting plans, beginning with Kevin J Curtin's churches, and continues to do so. The elegant worship chamber of St Patrick's Cathedral at Parramatta (Mitchell, Giurgula & Thorpe, 2003) is unusually arranged about a central line of altar, ambo and lectern with the pews facing on either side.

The [media]most broadly acclaimed of the postwar churches of these denominations is the Wentworth Memorial church, Vaucluse (Clarke, Gazzard & Yeomans, 1965). Its plan type is straightforward, but it is sited and formed in the emerging style of the Sydney School: this is a kind of romantic modernism inspired from Scandinavian and American sources. It is the best Sydney church of the latter half of the twentieth century.

With postwar migration came churches built to represent more diverse origins. In the 1960s the Sydenham Coptic Church of St Mary and St Mina converted a former Methodist church. This pattern is found in many Greek Orthodox churches, which are usually located in old Anglican churches. Their interiors are rich and glamorous, as seen at St Sophia's Greek Orthodox Church, Bourke Street, Surry Hills.

In the 1970s a new [media]form of church came to Sydney to house Pentecostal worship. Warehouses in industrial areas were appropriated for an auditorium style of church focussed on music, projected images, and preaching. No special liturgical furniture is provided. There are no windows. These are an experimental form of church, appropriating existing buildings in the same way as the early Christians appropriated houses for their meetings. Recently warehouse churches have been built new, and for other denominations, such as the Narellan Uniting church (which doubles as a gymnasium). Experimentation has broadened beyond that. The Church in the Market Place in Bondi Junction is a drop-in centre located in a shopping mall. The Presbyterian church in Cronulla (2003) is a hall built inside a new block of flats.

Sydney has a long and substantial history of architecture for Christian worship. A consistent way of building has not developed, but many threads have formed. Perhaps a theory of church architecture developed around appropriation will come to have a cultural impact similar to that of the churches in the first decades of European settlement. Or, with the recent building of prominent and identifiable mosques and temples of other religions, perhaps Sydney's Christians will resume building identifiable churches.

References

'A sequence of Presbyterian churches', Architecture Australia, March 1986

Clive Lucas, Stapleton & Partners, Christ Church St Laurence, 812a–814 George Street / 507 Pitt Street, Sydney: Conservation Management Plan, prepared for Christ Church St Laurence, 2002

Clive Lucas, Stapleton & Partners, St John's Anglican Church Precinct, Menangle Road, Camden: Conservation Management Plan, prepared for the Anglican Parish of St John, Camden, February 2004

Clive Lucas, Stapleton & Partners, St Patrick's Estate at Manly: Comments on Tanner's Review of the RCMP and Tanner's Addendum, prepared for Manly Council, 1998

Phillip Cox and Clive Lucas, Australian Colonial Architecture, Lansdowne Editions, Melbourne, 1978

HJ Hamlyn (ed), Churches of Romance and History, Tucker and Co Pty Ltd, 1938

Morton Herman, The Architecture of Victorian Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1956

Peter Reynolds, Lesley Muir and Joy Hughes, John Horbury Hunt: Radical Architect, 1838–1904, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002