The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Koreans

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Koreans in Sydney

The Korean community in Sydney first became palpable in the early 1970s. The community has continued to expand in numbers and nature. This is reflected by various structures around which the Korean community in Sydney is organised. Notable organisations include over 150 Korean-language Christian church congregations, multifarious business enterprises, and an established Korean language text and broadcast media which includes both local and imported materials and information.

[media]Although Australia's foremost individual Korean arrivals were mostly to Melbourne, the most sizeable and visible evidence of 'organised community' among Koreans is found indisputably in Sydney. The Korean Society of Sydney, the first of its kind in Australia, was established in Redfern in December 1968. Now based in the suburbs of Campsie and Croydon Park, the Society states it is the largest of its kind in the southern hemisphere.

The Korean community in Sydney may be considered from a number of different perspectives. For example, the community has been described as an aggregate of distinct groups: observers have identified 'waves' of migration, especially male migration, distinguishable by migration date or motivation; or more specifically, by length or circumstances of stay in Sydney; and 'generations' sorted by birthplace, or age at time of emigration. Alternatively, elements which are prevalent throughout the community have also been identified, notably Christianity, and also a strong capacity to assert Korean ethnic, cultural and national identity. Like any other community, the Korean community as an overall group encompasses a spectrum of smaller groups, each claiming different experiences and backgrounds, but nonetheless displaying a single identification as the Koreans in Sydney.

Early migration

The 1971 census recorded fewer than 500 residents of Korean birth in all of Australia. These were predominantly students or domestic workers who had arrived after 1921, that is, over a period of half a century. Over the decade following 1971, this figure would increase more than ninefold.

The period 1972–75 saw Australia's first significant influx of Koreans. This first wave of migrants, roughly 500-strong, settled mostly in Sydney. Indeed, the ethnic Korean population in Australia continues to concentrate itself primarily in Sydney. The next major influx of Korean migrants was in the 1980s, with two distinct groups or waves arriving in the middle and at the end of the decade respectively.

Amnesty migrants, 1970s

The first wave of Korean migration which took place in 1972–75 was triggered by circumstances largely beyond the domain of Australian authorities. It was during this period that the Republic of Korea (South Korea) began to withdraw its citizens from military and non-military service in the Vietnam War (1954–75). Rather than returning to Korea, many of these Koreans, mostly men, sought work and opportunity in other places, including the Americas, West Germany, the Middle East and South Vietnam. A few thousand arrived in Australia by air, mostly on tourist visas. Many overstayed their visas and took up employment. Of these 'illegal immigrants', approximately 500 were able to obtain residency as a result of the federal government's amnesty provisions. Many more were deported, especially for working illegally. The first such amnesty was introduced by the Whitlam Labor government in 1974. [1] 'Amnesty' was extended to all visa overstayers and their families. It also had the effect of attracting more Korean 'migrants-hopeful' to Australia, especially those then working outside Korea in countries including Iran, Saudi Arabia, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina, during the period of Korea's vigorous pursuit of foreign currency. Thus, some Koreans who arrived in Australia as late as 1979 were granted permanent residency by the 1980 amnesty, the last of its kind in Australia.

Most of these amnesty migrants settled in Sydney and, like many of their counterparts from other countries, rapidly entered 3-D – 'dirty, difficult and dangerous' – jobs. This included employment in metal refining or steel construction or welding. During the mid-1960s and 1970s Australian governments had begun to actively seek the expansion of manufacturing sectors, which depended on an expansion of labour. Amnesty migrants were commonly employed in menial labour, including cleaning, truck driving and delivery services.

Container migrants, 1980s and 1990s

In the years following 1980, the Korean population continued to grow as amnesty migrants were reunited with their families. However, the key reason for the growth of the Korean population in Sydney in the 1980s was actually the arrival of skilled migrants in the mid-1980s, and business migrants, whose rates of arrival first jumped in the late 1980s. Koreans in Sydney refer to a distinction between these well-equipped 'container migrants' on the one hand, and the 'empty-handed' amnesty migrants on the other.

Container migrants arrived on very different terms compared to amnesty migrants. In contrast to the relatively circumstance-driven settlement of those who arrived via the battleground of Vietnam, the bulk of Korean migration in the 1980s occurred after greater voluntary deliberation on the part of both the migrants and the Australian government. After the amnesties of 1974–80, the new decade heralded a re-tightening of immigration regulation. Of course in the broader scheme, the 1980s represented not so much a re-tightening as it did a fundamental aperture, in the sense that the policy door to Asian migration had been flung well and truly open.

Following the growth of Australia's manufacturing sector in the 1970s, the 1980s was a key period of expansion for the skilled work sector. Immigration policy was adjusted in accordance with this economic change, bringing an influx of skilled migrants and their families to the Korean community.

Upon arrival, skilled migrants entered government-provided English language education and generally were at leisure to perhaps stroll along the harbour or explore other Sydney attractions when not in class. However the task of re-establishing their livelihoods in Australia would prove more challenging. Most of these professionally trained Korean migrants would disappointingly find themselves in manual labour for want of English language proficiency. Similar sets of challenges met those Koreans who had arrived under the federal government's business migration initiatives.

[media]Introduced by the Fraser Liberal government of the late 1970s, 'business migration' was amplified under the Hawke Labor government after its second term which began in 1985. In the late 1980s, business migration accounted for over 40 per cent of Korean migration to Australia. [2] This 'entrepreneurial' migration was to continue through the 1990s, as distinct from skilled or professional migration.

In particular, the federal government intended business migration to enliven investment in the feeble economy. Korean business migrants arrived during the global economic downtime of the 1980s and the recession which Australia underwent through to the early 1990s. This may have made fine policy sense to the government; however the reality for business migrants and also skilled migrants was not as sensible. They have encountered language and cultural barriers which have hampered their employment and enterprise opportunities, and their aspirations and expectations have been profoundly frustrated, not least by economic conditions.

Health

The nature of the jobs undertaken by amnesty and container migrants has had direct impacts upon their health. Amnesty and skilled migrants have often developed physical ailments as a result of their employment in hard labour, usually in long shifts. In addition, they, especially skilled migrants, have suffered in their mental health as they found themselves in occupations which they had expected to avoid. Business migrants also suffered psychologically as they encountered various difficulties and disappointments in launching their livelihoods anew.

Business migrants often occupied themselves with sporting activities, having saved enough in Korea to be at leisure to do so. Some maintained their business in Korea and thus supported themselves. These people were hardly pleased to be fishing or playing golf when they had hoped to direct successful businesses; however they mostly avoided the work-related injuries and chemical-related cancers which were known to be prevalent amongst amnesty and some skilled migrants. After 15 or so years of hard labour, amnesty and, in turn, skilled migrants experienced disproportionate mortality rates. 'Iminppyeong' ('migration-itis') became a recognised condition within the Korean community, where migrants often fell seriously ill after years of relentless exertion in difficult jobs, often just as their labour was beginning to promise amelioration. [3]

Asian Economic Crisis, 1997

Australia experienced internal and immediate economic downturn from the 1980s through to the early 1990s. Skilled and business migrants, migrants of essentially economic interest, had arrived during this unfavourable period. By the late 1990s, the federal government had introduced economic reforms which would help support Australia while the Asian economies around it crashed. Despite Australia's geographic location and its degree of economic integration within the Asia-Pacific, the national economy is generally understood as having weathered the Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s. However economic calamity in the homeland would reverberate through the Korean community in Sydney. The IMF (International Monetary Fund) intervened in the South Korean economy on November 23, 1997, following the collapse of the Korean won, initiating a period which Koreans commonly refer to as 'the IMF [intervention] crisis'.

'The IMF wanderers'

As the Korean economy began to claw its way back to the surface, the Korean community in Sydney underwent significant socio-economic change. Many dynamics shifted, adumbrating trends which, a decade later, are patent. While the flow of Korean tourists to Sydney dried up, the presence of temporary migrants began to be felt acutely. This was due to the fact that, although the combined numbers of Koreans arriving on working holiday and visitor visas actually fell after 1997, they were no longer mostly university students but instead the newly unemployed, bankrupt or otherwise dislodged citizens of Korea. The more established members of the community promptly dubbed the new arrivals 'IMF bangnangja' ('drifting people'). [4]

Figure 1 shows how the number of movements to and from Korea recorded by Australia plummeted after 1997 and has taken about a decade to recover. The sharp fall in numbers of Korean tourists spelled a serious decline in business for many otherwise established Koreans in Sydney. At the same time, the competition for jobs in these and related enterprises increased. Consequently, the Korean community in Sydney witnessed the closure of many of its businesses and a fall in wages. There was unmistakeable tension between the Korean community's gupo and sinpo, or 'old' and 'new' migrants. Newly arrived Koreans reported instances of established migrant employers withholding pay. The established migrant community scorned the newcomers' lack of English skills and bemoaned their ignorance of Australian norms. Being the suburb with the highest concentration of Koreans during this period, Campsie was the epicentre of this community-wide upheaval. In recent years Strathfield has emerged as Sydney's avant-garde 'Korean town'. The 2006 Census recorded 1,943 Strathfield residents claiming Korean ancestry, and 1,429 in Campsie. [5]

Later arrivals

The Asian Economic Crisis represented a watershed for the homeland and its stock of Australian immigrants. As conditions in Korea improved and its rhetoric of globalisation gathered pace, Sydney's Korean community would begin to see fewer permanent arrivals and more sojourners. The contrast between 'old' and 'new' would solidify into that between 'established' and 'temporary'.

Temporary migrants, 2000s

Over the past decade, Korea has consistently been a key source of overseas students for Australia, surpassed only by China and recently India. [6] Also, the number of working holiday visas granted to Koreans has mushroomed, with a 243 per cent increase between 2003 and 2008. Meanwhile, the number of settler arrivals fell after 1990. [7] These trends indicate that the growth of the Korean community is increasingly dependent on temporary migration and less dependent on permanent migration.

1st versus '1.5' and 2nd generations

As the community becomes more settled, natural births will increasingly contribute to the growth of the community. In the more established communities in the diaspora, such as those of Hawaii and Los Angeles, Koreans count themselves back at least eight generations. In Sydney, younger Koreans are still largely viewed as an emergent element of the Korean community. In reality, the Korean community in Sydney can count its third generation at the very least, and Australian-born Koreans are certainly not without positions of leadership and responsibility within the organisational structures of the Korean community. Nonetheless it is undoubtedly those amongst the major founding migrant groups described above who currently retain overall leadership of the community. Tellingly, perhaps, in 2008 the Korean Society of Sydney's second forum for Korean youth was held in the Society's hall in Campsie, despite many students' preference for the location of Strathfield. Asserting the importance of meeting in the Establishment building, in an unprecedented move the Society organised transport between Strathfield and Campsie for forum attendees. [8]

Korean migrants all over the world draw a well-understood distinction between the 'one-point-five' and second generations. In Australia, the second generation broadly denotes the Australian-born children of Korean immigrants. These immigrants comprise the first generation, such as amnesty and container migrants, and were generally adults at their time of arrival in Australia. [media]The 1.5 generation describes those Korean-born who arrived in Australia at a young age, especially with their first-generation migrant parents, and these are popularly characterised as having a reasonably deep appreciation for both the Korean and Australian cultures and languages, in contrast to the second generation who are stereotyped or lamented as being dismissive of Korean culture and as having relatively limited Korean language proficiency, instead being steeped in the Australian way of life. It is not uncommon for members of these later generations to achieve high academic standards at school, and many are employed in medical, legal, political and other esteemed professions.

Christianity

Organised religion, especially Christianity, plays a central role in the life of the Korean community in Sydney. Sydney's first ethnic Korean church was established in 1974; by 1993 there were over 70 such congregations in Australia, of which more than 50 were located in Sydney. [9]

In 2009 there are at least 151 ethnic Korean Protestant churches in Sydney, constituting well over half the figure for all of Australia. [10] The reasons for this staggering growth are by no means straightforward; however, a couple of clear factors are the presence of many theological graduates from Korea, and church schism. [11] This phenomenon of church growth is not unique to Sydney but recognised in Korean churches throughout the homeland and the diaspora. [12]

The Uniting Church in Australia has codified provisions and practices relating to its many ethnic Korean congregations in a single document. There are some significant differences between the operation of the 'Korean parish' and the conventional parishes; for example, in some cases the minister of a Korean congregation may receive lifetime tenure. [13] There are also stipulations regarding the status and retirement of elders. A fair assessment would be that the document is primarily about giving Koreans the latitude to maintain Korean congregational conventions whilst remaining within the broader denominational structure.

The Korean Catholic Church of Sydney Archdiocese is located in Silverwater. Roman Catholic mass is held in Korean in several suburbs, including Baulkham Hills, Belmore, Marsfield, North Auburn, Paddington, Parramatta and Waitara. Apart from there being fewer Korean Catholics than Protestants, the number of Catholic congregations can be contrasted to the number of Protestant congregations in that according to the nature of the polity of the Roman Catholic Church, Catholics do not ordinarily experience church schism.

The church is central to the migrant experience of most of Sydney's Koreans. As well as being a place of worship, it is a key site of ethnic identity affirmation and an important point of social contact with other Koreans.

Buddhism

While Buddhism is a major religion in Korea, its influence in the homeland has not been significantly transferred to the Korean community in Sydney. The first Korean Buddhist temple was established in 1986. Disgruntled members of the churches sometimes are to be found in Sydney's Korean Buddhist temples. These are found in a handful of suburbs, including Belfield, Belmore, Burwood, Punchbowl and Woodford.

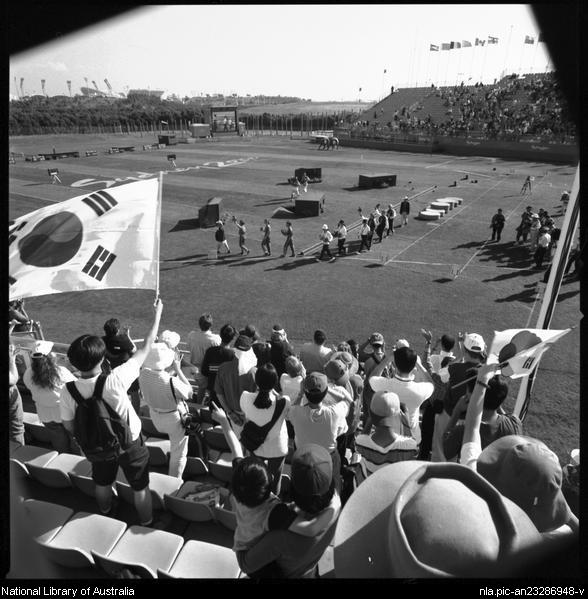

Maintaining Korean ethnicity

[media]Apart from its religious collectives, the Korean community in Sydney has numerous other associations and clubs. A few well-established examples include the Korean Chamber of Commerce in Australia, based in Campsie and Canterbury; the Korean Vietnam Veterans' Association of Australia; and the Korean Judo Association of Australia. Sport is a popular means for Koreans to gather. For example, many enjoy playing competitive and recreational golf, soccer, swimming, table tennis, bowling and badminton. Each year, many travel to Korea where they play in competitions attended primarily by overseas Koreans.

Koreans [media]in Sydney are able to watch the latest Korean films and television serials either by subscribing to the satellite television service which broadcasts Korean channels, or by hiring out recordings from Korean video rental stores. Sydney's established Korean language print media circulates information pertaining to both the local and the homeland.

Data from the 1996 Census indicates that 63.1 per cent of Australia's eligible Korean-born had been naturalised, a relatively low figure, particularly compared to other groups of Asian-born migrants. [14] It is difficult to infer the reasons for this low figure; however among those who have taken up Australian citizenship, it is possible to observe significant degrees of political engagement. A handful of Korean-born Sydneysiders have successfully been elected to local councils, notably Canterbury and Strathfield. In September 2008, 1.5 generation Korean-Australian Keith Kwon was elected Mayor of Strathfield Council, having served four years as a councillor.

[media]The Korean community in Sydney is, by any measure, dynamic. There is much internal variation amongst its members, their backgrounds and experiences. The community is not without its points of tension. With its penchant for names such as 'container migrant', '1.5 generation' or 'wild goose parent' (usually a mother, who migrates for the purpose of her child's education while being financially supported by her spouse back in Korea), the community as a whole may appear to be as riven as its schismatic churches. However, initiatives such as the Korean Society's annual youth forum, the growth of English language ministries within the ethnic Korean churches, the burgeoning voice of Korean overseas students on Sydney's university campuses, and the vibrancy of Sydney's Korean media suggest that the community does share a collective awareness and is prepared to actively engage this awareness.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australia, Profile: Ancestry 1st Response (ANC1P) by Persons, Place of Usual Residence, table, retrieved from CDATA Online, ABS, Canberra, 2007

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 'Table 3: Short-term Movement, Visitor Arrivals - Selected Countries of Residence: Trend', Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia (cat no 3401.0), June 2009, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, 2009

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Perspectives on Migrants, 2009 (cat. no. 3416.0), available at <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3416.0Main%20Features99992009?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3416.0&issue=2009&num=&view=>, viewed 24 October, 2009

J Coughlan, 'Korean-Australians: Present and impending contributions to Australia's future – An outsider's perspective', Cross-Culture Journal of Theology & Ministerial Practice, vol 1 no 1, October 2008, pp 51–62

Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC), Immigration Update: July to December 2008, National Communications Branch of the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Belconnen, 2009

Statistics Section, Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (DIMA), Immigration: Federation to Century's End 1901-2000, DIMA, Belconnen, 2001

G-S Han, 'Economic aspects of Korean churches in Sydney and their expansion', Journal of Intercultural Studies: An International Journal, vol 15 no 2, 1994, pp 3–34

G-S Han, Health and Medicine under Capitalism: Korean Immigrants in Australia, Associated University Presses, London, 2000

G-S Han, 'Immigrant life and work involvement: Korean men in Australia', Journal of Intercultural Studies: An International Journal, vol 20 no 1, 1999, pp 5–29

G-S Han, 'Korean Christianity in multicultural Australia: Is it dialogical or segregating Koreans?', Studies in World Christianity, vol 10 no 1, 2004, pp 114–135

G-S Han, 'Koreans in Australia', in J Jupp (ed), The Australian People , Cambridge University Press, Oakleigh, 2001

G-S Han, 'Leaping out of the well and into the world: A reflection on the Korean community in Australia with reference to identity', Cross-Culture Journal of Theology & Ministerial Practice, vol 1 no 1, October 2008, pp 33–50

G-S Han, 'An overview of the life of Koreans in Sydney and their religious activities', Korea Journal of Population and Development, vol 35 no 2, 1994, pp 67–76

G-S Han, 'The pathways of Korean migration to Australia', Korean Social Science Journal, vol 10 no 1, 2003, pp 31-52

G-S Han, Social Sources of Church Growth: Korean Churches in the Homeland and Overseas, University Press of America, Lanham, 1994

Hojuhanin 50nyeonsa Pyeonchanwiwonhoe (50 Year History of Koreans in Australia Editorial Committee) (eds), 50 Year History of Koreans in Australia, Kyeongjin Park, Croydon Park, 2008

C Inglis and C-T Wu, 'The “new” migration of Asian skills and capital to Australia', in C Inglis, S Gunasekaran, G Sullivan and C-T Wu (eds), Asians in Australia: The Dynamics of Migration and Settlement, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1992

Keuriseuchan Ribyu (Christian Review), edition 235, The Christian Times Australia, Sydney, July 2009

Young-Sung Kim, 'Migration and residential mobility of Koreans in Sydney, Australia', Jirihak yeon-gu (Research in Geography Studies), vol 42 no 2, 2008, pp 513–525

K Lim, 'A new wave in the Sydney Korean Society', The Sydney Korean Society Bulletin, vol 2, 15 May, 2008, pp 1, 5

C Rhodes, 'Amnesty for Illegal Aliens: The Australian Experience', Review of Policy Research, vol 5 no 3, 1986, pp 566–581

Byung-Soo Seol, 'The Sydney Korean community and "the IMF drifting people"', People and Place, vol 7 no 2, 1999, pp 23–33

Uniting Church in Australia, Hojuyeonhapgyohoe haningyohoereul wihan daeche gyujeong (Overview and rules for Korean churches in the Uniting Church in Australia), March, 1999

MD Yang, Australia and Korea: The 120 Years of History, Yonsei University Press, Seoul, 2009

Notes

[1] C Rhodes, 'Amnesty for Illegal Aliens: The Australian Experience', Review of Policy Research, vol 5 no 3, 1986, p 568

[2] C Inglis and C-T Wu, 'The "new" migration of Asian skills and capital to Australia', in C Inglis, S Gunasekaran, G Sullivan and C-T Wu (eds), Asians in Australia: The Dynamics of Migration and Settlement, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1992, p 199

[3] G-S Han, Health and Medicine under Capitalism: Korean Immigrants in Australia, Associated University Presses, London, 2000, p 122

[4] B-S Seol, 'The Sydney Korean community and "the IMF drifting people"', People and Place, vol 7 no 2, 1999, p 23

[5] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australia, Profile: Ancestry 1st Response (ANC1P) by Persons, Place of Usual Residence, table, retrieved from CDATA 2006 Online edition, ABS, Canberra, 2007. These figures are indicative only and are provided with caution. Although 36,940 Census respondents in Greater Sydney claimed Korean ancestry, it is popularly estimated that today there this number approximately doubles when undocumented long-term residents are taken into account. When short-term visitors such as tourists are also counted, it is estimated that there are up to 100,000 ethnic Koreans present in Sydney at any given time.

[6] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Perspectives on Migrants, 2009 (cat no 3416.0), available at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3416.0Main%20Features99992009?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3416.0&issue=2009&num=&view=, accessed 24 October 2009

[7] Statistics Section, Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (DIMA), Immigration: Federation to Century's End 1901–2000, DIMA, Belconnen, 2001

[8] K Lim, 'A new wave in the Sydney Korean Society', The Sydney Korean Society Bulletin, vol 2, 15 May, 2008, p 1

[9] G-S Han, Social Sources of Church Growth: Korean Churches in the Homeland and Overseas, University Press of America, Lanham, 1994, pp 4, 107

[10] Keuriseuchan ribyu (Christian Review), edition 235, The Christian Times Australia, Sydney, July 2009, pp 96-7. It is estimated that there are at least another 100 churches in Greater Sydney which are not listed in this directory

[11] G-S Han, Social Sources of Church Growth: Korean Churches in the Homeland and Overseas, University Press of America, Lanham, 1994, p 150

[12] G-S Han, Social Sources of Church Growth: Korean Churches in the Homeland and Overseas, University Press of America, Lanham, 1994, p 7

[13] Uniting Church in Australia, Hojuyeonhapgyohoe haningyohoereul wihan daeche gyujeong (Overview and rules for Korean churches in the Uniting Church in Australia), March, 1999, section 2.7.6

[14] J Coughlan, 'Korean-Australians: Present and impending contributions to Australia's future – An outsider's perspective', Cross-Culture Journal of Theology & Ministerial Practice, vol 1 no 1, October 2008, p 56

.