The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Economy

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Economy

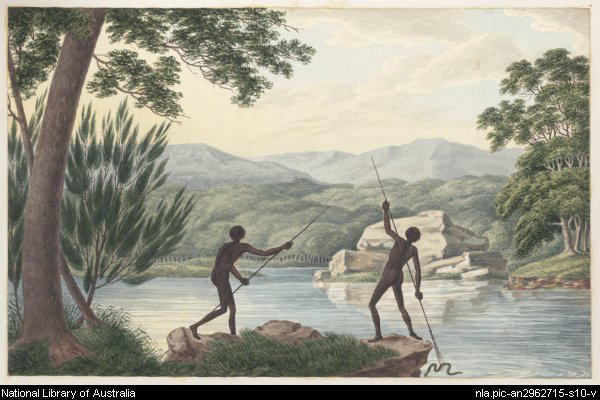

For thousands of years before 1788, the Indigenous clans living on the Cumberland Plain – now the site of metropolitan Sydney – adapted well to the availability, or scarcity, of resources within their various domains. Along the coast, the people of the harbour and the beaches – the Gadigal of the Eora and the Tharawal – lived off the local animals, plants and marine life. [media]Further inland, along the rivers and in the scrub country, the Dharug people used traps for hunting, collected plant food and fished the rivers and creeks, while to the north the Guringai had adapted to their more rugged terrain, living off the land and fishing in the various rivers that fed into the harbour. All these tribes were predominantly hunter-gatherers, using the local flora and fauna for their survival.

But with the advent of 'the First Fleet' in 1788, all that began to change.

The closed convict 'economy' and the Commissariat

When the convict colony of Botany Bay was established, the prevailing economic theory was mercantilism, a collection of policies designed to keep the state prosperous by close economic regulation. A simplistic theory, mercantilism held that the prosperity of a nation was dependent upon its supply of 'capital' – its holdings of bullion, mainly gold and silver. Mercantilism also held that the state could increase its 'capital' through a positive balance of trade with other nations – by exporting more than it imported in a world where the volume of international trade was thought to be static. Mercantilists argued that the government should further these efforts by playing a protectionist role in the economy, encouraging exports and discouraging imports, notably through the use of tariffs and subsidies. [1] Between 1600 and 1800 most of the states of western Europe were heavily influenced by such policies and their implementation. These theories account for some of the more unusual aspects of the convict colony's early structure and economy.

Little provision was made for managing an 'economy' – the presumption of a closed convict system meant that commercial market activity was neither envisaged nor to be encouraged. Central to the economy was the Commissariat – the provider of all necessities for the fledgling settlement. It was expected that the convicts would grow the food that the Commissariat Store would take in and then allocate out to the colony's inhabitants. The Commissariat could also issue Bills of Exchange (drawn on London) if it needed to purchase goods from visiting ships. Occasional shipments of currency were also available from 'home'. Fundamental to this scheme was the production of food and raw materials by convicts working on government farms. [2]

Trading for food and rum

But necessity proved otherwise. Those who arrived with the First Fleet under Governor Arthur Phillip had only two years' provisions with them and no knowledge of farming in Sydney's environment. With unproductive soils around Sydney Cove, a series of poor harvests meant that the first arrivals nearly starved to death. Clearly, new approaches had to be tried. Land grants were made to officers of the New South Wales Corps, and convicts assigned to work their farms, in an attempt to fill the food gap. Under Phillip's successor, Francis Grose, many of the officers of the New South Wales Corps were given quite large land grants: in 1794, John Macarthur received 400 acres (162 hectares) of good farming land at Rose Hill (later Parramatta). This was seen as a better way of keeping the colony alive than buying in food supplies, although early governors occasionally sent ships to India, Indonesia and the Cape of Good Hope to buy food for the starving population.

[media]But the food supply was not the only scarcity the colony faced: there was a lack of goods generally, such as farm implements, building materials, and 'industrial' equipment. Ships calling in at Sydney might have the requisite materials, and Grose tolerated the collusive tendering by officers of the Corps for these newly arrived cargoes. Members of the Corps, such as Macarthur, Grose, Paterson, Johnston, Rowley and Foveaux, purchased inbound cargoes, and sometimes even chartered entire ships. Indeed, Grose himself was a partner in chartering a ship laden with a 'speculative cargo'. [3] Opportunities for profit were seen by members of the New South Wales Corps, and many became entrepreneurs who were willing to take on the role of bringing necessities into the colony. Their trade in alcohol led to the Corps acquiring the name 'the Rum Corps'.

John Macarthur was paymaster for the colony, with the authority to issue bills of exchange which were the main form of currency. [4] As a result, the officers controlled not only the flow of imports into the colony, but its money supply as well.

Convict labour, farming success and expansion

[media]Despite its difficulties, the colony had several potential economic advantages. One was the availability of convict labour. Governor Macquarie, who took office in 1810 after the so-called 'Rum Rebellion', used this resource to pursue another line of activity with economic benefits: the construction of much needed economic and social infrastructure. [media]On his return to England in the early 1820s, Macquarie listed 265 public buildings such as convict barracks, a hospital, a lighthouse, courthouses, churches and schools built during his period as governor.

Another advantage the colony had was its situation on a harbour with various rivers flowing into it. Waterways had the advantage that no capital outlay was required to create the 'carriageway', and goods could be moved cheaply over long distances, including foodstuffs from the gradually developing outlying areas. After better soils were discovered at the head of the Parramatta River, Governor Phillip decided to set up a farm there, and convicts were sent to the site as early as November 1788. [media]Land was cleared and planted with crops. James Ruse set up Experiment Farm there a year later: the land was later granted to him, inaugurating private farming.

The need to feed the colony encouraged expansion, as the land further inland was far more suitable for agriculture. The Hawkesbury–Nepean area had productive potential and a river providing transport back to Sydney Town. Agriculture and pasturage developed in the Penrith and Windsor districts, in what is now western Sydney.

Grazing was soon established, initially as a food supply and later as a potential wool export industry. In 1795, cattle that had strayed from the original settlement at Farm Cove were discovered in the Camden area. This prompted Governor Hunter to visit the area, which he named Cowpastures. In 1803 Governor King instructed that the cattle herd be preserved, and in early 1805 two constables were settled there to ensure that the herd was protected. A far-sighted entrepreneur, John Macarthur first saw the possibilities inherent in sheep breeding, and in 1803 Governor King was ordered by Lord Camden, the Colonial Secretary, to grant John Macarthur 'not less than 5,000 acres' (2023 hectares) for this purpose in the Cowpastures area. [media]Macarthur was also allowed to import the first pure merino rams and ewes from the Royal Stud at Kew.

[media]As these outlying activities developed across the Cumberland Plain, townships grew at Parramatta, Windsor, Richmond, Liverpool and Campbelltown. Roads were needed to establish permanent communications with them, and Macquarie had several important roads built. The road to Parramatta was completed in April 1811 and a road to the South Head by mid-1811. Other roads connecting the outlying settlements to Sydney Town were constructed over the next decade. The Blue Mountains were crossed in 1813, potentially opening up the interior. Under Macquarie's stewardship the gradual transformation of the economy began to occur in earnest, and the infrastructure necessary for future economic growth was created.

Currency and finance for the colony

One major problem for everyday survival was the absence of a stable monetary system. Promissory notes, British Treasury bills, foreign coins, rum and barter were all substituted for cash, with disastrous results for emerging economic activity. Macquarie addressed some of these economic issues in a constructive, civic way. [media]To stop the outflow of currency, he converted the colony's supply of Spanish silver dollars into a purely local coinage, by stamping out a hole in the middle, creating two coins – the 'holey dollar' and 'the dump'. Both became locally acceptable currency.

Macquarie saw the need for a viable financial institution to fund economic activity, and in 1817 he authorised the establishment of the Bank of New South Wales, despite strong opposition from the Colonial Office in London. A bank able to raise funds for loans and to underpin development, with its board full of local entrepreneurs, gave a boost to the colony's economic base. [5] The bank's first president and chairman of the board was Macquarie's secretary, John Thomas Campbell, and the first directors and shareholders included well-known characters in early colonial history, such as the emancipists D'Arcy Wentworth and William Redfern. The bank opened its doors for business in April 1817 in premises in Macquarie Place, Sydney, leased from Mary Reibey, an ex-convict turned businesswoman.

Macquarie also added to the entrepreneurial mix by encouraging skilled convicts to contribute to the colony's development and rewarding good work by granting pardons. Many ex-convicts were to make important contributions to the colony's development: among them were the Colonial Architect Francis Greenway; the businesswoman Mary Reibey; the surgeon, magistrate and landowner William Redfern; the entrepreneur Simeon Lord; the merchant and miller Daniel Cooper; the storekeeper, ship owner and investor Solomon Levey; and the landowner and merchant Samuel Terry, who became known as 'The Botany Bay Rothschild'.

Shipping and trade

In 1789 a small vessel, the Rose Hill Packet, was built for transporting goods and people along the Parramatta River to the fledgling settlement there. But since early governors were also anxious to prevent convicts escaping, in 1791 the building of vessels more than 14 feet (4.3 metres) in length was prohibited, although this regulation was later relaxed.

One major problem for the emerging colonial economy was that it fell within the domain of the East India Company, an English chartered company formed in 1600 for trade with east and south-east Asia and India. The company acted as a virtual state, exercising substantial power over various areas of Asia and the subcontinent, holding monopoly powers for trade and enforcing restrictions on shipbuilding throughout the Indian and Pacific oceans. Botany Bay, being a Crown colony, came under these restrictions in its early years, and it was not until 1813 that the British government took away the company's absolute powers (which remained only in the trade with China until 1833), thus allowing for overseas trade and shipbuilding to develop in Sydney Town.

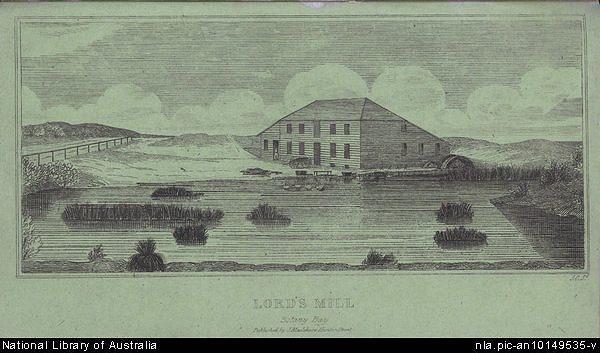

As a port city, it was inevitable that Sydney's economic development would feature various maritime industries, and in time both coastal and international shipping emerged. Internally, cheap water transport allowed industries to develop around the harbour and along the rivers. The building of Sydney Town stimulated a number of industries: timber was cut in forests around the settlement, while lime-burners gathered in the bays of the harbour and along the ocean beaches where natural shell banks and Aboriginal middens provided a source of lime for use in mortar. Brick-making also appeared early, earning George Street south of Bathurst Street its common appellation of 'Brickfield Hill'.[media] Windmills to grind flour were early additions to the landscape. As population increased, other industries gradually appeared: clothing makers, boot and shoe makers, and barbers, as well as the 'entertainment' industries – pubs, illicit stills, theatre and the arts.

By the 1820s, a new economic system was clearly emerging: superimposed on the command economy was an emerging market system. Though the colony of New South Wales covered the whole of eastern Australia, one writer noted that the City of Sydney 'can even be conceived of as being the New South Wales economy'. [6] The new economy had its origins in the greed and arrogance of the early officers of the Rum Corps, but it also gained from the expertise and entrepreneurship of the emancipists, who used the freedom and encouragement Macquarie had given them to advance their fortunes in this new land.

A free population

Sydney Town evolved rapidly over the [media]decades from 1820, and though the number of convict arrivals increased, the proportion of convicts in the total population declined. The greater flow of convicts from Britain resulted partly from the abolition there of the death penalty for over 200 offences, replaced by transportation. Between 1821 and 1830, 33,000 convicts were sent to New South Wales, many of whom went to rural areas, as workers on farms and in the rapidly expanding pastoral industry. [7] But population growth was also affected by the British government's plans for free settlement. Edward Gibbon Wakefield's ideas on 'systematic colonisation' – of substituting land sales for land grants, and using the money raised to finance immigration – were implemented from the early 1830s, and between 1831 and 1840 about 40,000 free, and often subsidised, immigrants arrived, a figure dwarfed by the 76,000 who arrived during the 1840s, after convict transportation had ceased.

There was also natural increase, as more and more 'native-born' Sydneysiders appeared, and a new 'species' was identified – the currency lads and lasses, who often went 'up country' for periods, being both better adapted and better connected than the newcomers.

Sydney's growing population was gainfully employed in a range of industries, some old, some new. Its location in the south-west Pacific meant that hunting seals for their skins and oil and whales for their oil and whalebone were soon industries of importance. Whales had been seen early on, even in Sydney Harbour. In July 1790 a midshipman and two marines drowned after their boat was sucked down into the vortex when a whale lifted it out of the water and then dived.

Maritime prosperity

With the curtailment of the East India Company's powers in 1813, the maritime industries flourished. The early governors had certainly been aware of the potential of maritime industries for the colony's economy: Phillip had one of the Third Fleet convict transports refitted to explore the southern seas, and it reported on the abundance of whales, seals and fish in the area.

[media]Whaling and sealing were the first staples that dominated the economy's exports and, even though relatively unprocessed, led to major growth and economic development of the area, through a range of linkages. These included ship building and repairs, ships' chandlery and cooperage, increased cash inflow from the sale of products of the industry, and development of banking and financial institutions to handle these flows.

While sealing and whaling fuelled growth in Sydney in the early decades, by the 1820s the development of the fine wool industry in the colony allowed for far greater export-stimulated economic growth. As the pastoral industry expanded into the interior of New South Wales, its product – in increasing demand from the factories and mills of Britain and western Europe – passed through the port of Sydney, spreading largesse in its wake. The colony's economic development was based increasingly upon the production and export of fine wool.

To lubricate the burgeoning economic activity, more banks appeared in Sydney, joining the Bank of New South Wales. Many of these were short-lived ventures: some, such as the Sydney Commercial Bank or the Australian Agricultural Bank, never really got off the ground; others, such as the Waterloo Company, folded early; a few, such as the Bank of Australia or the Sydney Banking Company, collapsed in the depression of the 1840s. There were some, such as the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, that lived on, with descendents among the 'big four' Australian banks of the twenty-first century.

The export-led boom translated into great prosperity for Sydney Town, and growth in many industries associated with exports. As one historian has noted, even by 1826

there were twenty-two shipping agents, eleven auctioneers, a chamber of commerce, two banks (which paid dividends of 40 per cent on the value of their shares) and three newspapers. There were four Sydney-based whaling vessels and six sealing vessels; foreign ships were transporting cargo from India, Brazil and Canton. On the manufacturing side, woollen textiles were being produced by Simeon Lord's factory at Botany and at the female factory in Parramatta, and rope was being manufactured from New Zealand flax. [8]

An entrepôt was lustily growing.

Despite the population increase, labour supply was always short, not so much in the city but in the rural areas and there were various schemes for importing cheap and captive labour – Indians, Chinese or Pacific Islanders who had less ability to disappear into a population of predominantly British and Irish descent. But as the urban population increased, opposition grew to bringing in cheap labour that could undercut workers' wages. The appearance of an urban bourgeoisie, allied with urban workers, led to the emergence of political factions outside the old pastoralist-centred establishment. [9]

The city grows

One sign of Sydney's growing financial maturity was the gradual emergence of a defined central business district. [10] Early decisions of the governors about the placement of the settlement and the allocation of land had long-term ramifications for the shape of Sydney. A building boom took place in Sydney in the late 1830s, with associated demand for bricks and mortar, timber, furnishings and other household accessories. Such stimulus also saw retailing flourish, with new stores such as David Jones appearing. It was a walking city, and commerce, retailing and residential life were located cheek-to-cheek.

In 1828, Sydney spread from Cockle Bay on the west to Hyde Park on the east, and south to Brickfield Hill, holding a population of 11,000. The Rocks and the streets behind Darling Harbour were the most densely populated areas. But with growing population and affluence, those signifiers of civilisation – toll gates and inns – gradually appeared on the roads snaking out from the coastal settlement to the inland centres of economic activity. [11] And it was often around these roads that suburban development took place, and new habitations and industries emerged.

[media]Sydney's first 'suburban' developments were initially in areas to the south and south-west of the harbour, along or near the Parramatta Road. These areas also had early factory developments, with a distillery and brewery in Chippendale, a steam-powered mill built in Pyrmont in 1815, with wharves, warehouses and factories quickly following within the town boundaries. John Harris's Ultimo estate, however, remained farming land into the 1850s, when it was subdivided for suburban development. Even in the east, long home to the elite and their villas and little else, suburbanisation began after the construction of major public buildings along the South Head Road encouraged a wave of expansion there. A new suburb appeared in the 1840s around the military barracks in Paddington, with the requisite pubs and brothels for the soldiery. Surry Hills, and later Darlinghurst and Paddington, grew up as part of this early in-fill suburban expansion.

A prosperous society saw some innovative institutions appear: the New South Wales Savings Bank had been set up in 1819, as a place for convict monies to be deposited, but as the free 'labouring class' grew, the Savings Bank of New South Wales was established in 1832, taking deposits from the artisan and commercial classes, as well as taking over the old convict deposits. The following year, a Mechanics School of Arts was also established, to encourage the 'artisan classes' to further their education 'through public lectures and classes, and the establishment of a library': this facilitated the spread of both trade skills and general knowledge, including basic reading and maths abilities. Sydney became a modern town when gas lighting came to the city's streets in 1841.

Depression in the forties

A small outpost of the British Empire was crucially dependent on the economic health of the 'motherland', and as Britain experienced fluctuations in its economy, Sydney also felt the shock waves. The over-rapid expansion of the pastoral industry, with growing debt, declining returns after moving into areas of lesser and diminishing productivity, and with wool prices plummeting in England for some years, provided the local trigger for collapse. Financed by increasing debt to British lenders, the colony's major export industry, fine wool, collapsed dramatically, with repercussions in the city. By 1841 the colony was experiencing a major depression: sheep, once providers of the 'golden fleece', were now boiled down for tallow and fat on the outskirts of town.

The 'outer settlements' also began to take their own economic paths. The Windsor district, where the first settlers arrived to farm their 30 acres (12 hectares) in 1794, supplied fresh produce to Sydney, which continues today. In the Cowpastures area, in 1836 John Macarthur's sons had a township surveyed. [media]Land was offered for sale in 1840 in 100 allotments of half an acre each, and from then until the early 1860s the Camden district grew. At Parramatta, the end of convict transportation in the 1840s meant the withdrawal of the imperial garrison and the loss of its financial expenditure. The local economy suffered and Parramatta was no longer seen as a possible alternative 'capital' to Sydney.

By the end of the 1840s a capitalist economy was clearly in place on the Cumberland Plain. Old mercantilist ideas had been falling into disfavour from the late eighteenth century, as the free trade arguments of Adam Smith and the other classical economists took hold. But the depression of the 1840s showed that market forces, left unregulated, could have disastrous consequences. And while the depression was over by 1845, it was a gift of nature far from the city that set Sydney on the fast road to prosperity again.

The 'long boom'

The discovery of gold in Ophir near Bathurst in rural New South Wales launched Sydney into its first 'golden age'. Thousands of hopeful diggers came through Sydney, and it was also through Sydney that the bullion flowed out. Many failed to make their fortune on the goldfields and drifted back to the city, and this population stimulus deepened and widened economic activities. Sydney's population grew, from this influx and also from later immigration flows, from just under 40,000 in 1851 to about 150,000 in 1871 and nearly half a million in 1901. [media]And while gold became a new staple from the middle of the nineteenth century, wool, wheat and minerals other than gold became major exports later in the nineteenth century.

These boom conditions saw wide-ranging manufacturing development in Sydney, responding to demand from both the city and its hinterland: 'bricks and paving tiles, sanitary ware and drainage pipes…were manufactured,' [12] using cheap raw materials from in and around Sydney. Because of Sydney's distance from other centres and high transport costs, light industries, such as textiles, clothing, footwear, foundry and general engineering, could flourish in Sydney, free from import competition, especially if they used local raw materials. Repairs and maintenance were the major activities of the emerging heavy industries, and names such as Mort's Dock and PN Russell & Co Engineering passed into the city's history. [media]Giant wool stores around Sydney Cove and Darling Harbour attested to the ongoing role of wool in the city's growth.

Political manoeuvring ensured that city interests were never overlooked, even as the rural export industries responded to growing overseas demand for colonial products. To stop rural produce being transported by river boats down the Murray–Darling system and then overland to Melbourne, New South Wales's Sydney-centric rail network ensured that the goods flowed into Sydney and out of its port. This worked to the city's benefit, in commerce and banking, transport, wharfage and other ancillary industries of the export trades, and in urban jobs . [13]

[media]Though an early historian noted that 'From 1874, money commenced to flow into the colony largely for investment purposes', [14] this had been happening since the earliest days, and it went in roughly equal parts to the public and private sectors. [15] The London capital market underpinned the city's growing wealth, with government borrowings financing major infrastructure projects – roads, railways, bridges, docks, and courthouses, schools and hospitals, overseen by a large Public Works Department [16] – although water supply and sewerage were neglected, creating subsequent health problems.

The wealth of the city was also seen in its impressive buildings, both public and private, created from Pyrmont's golden sandstone. One visitor, Richard Twopeny, noted in Town Life in Australia in 1881 that

although Sydney is poorly laid out, it must not be imagined that it is poorly built … the handsomest are the Treasury, the Colonial Secretary's Office, and the Lands Office … The Colonial Secretary's Office is … lofty, massive and dignified outwardly, elegant and spacious inside …' [17]

There were less concrete riches too. Twopeny also observed that the Sydney Morning Herald was 'the richest newspaper property in Australia. It has correspondents in almost every capital in Europe, including St. Petersburg'. [18]

Late-nineteenth-century life in Sydney

While many of the public buildings were fine examples of provincial architecture, private construction was not always so sound. The growing population required housing, and this led to a developer-led building boom, with domestic dwellings

of two broad types: old buildings that had been poorly maintained, and newer buildings that were jerry built… [19]

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Sydney extended to the municipalities of Glebe, Randwick, Waverley, Woollahra, Marrickville, Newtown, Paddington and Balmain. By the turn of the century, Sydney had overtaken 'marvellous Melbourne' as the continent's largest city. Despite its 'boom town' feel, not all visitors were impressed with Sydney: Twopeny, after commenting glowingly on the setting of the city – its harbour, the gardens of the suburban villas, and places with 'a view fit for the gods', despairingly observed: 'One feels quite angry with the town for being so unworthy of its site”. [20]

One effect of the boom conditions was easy credit, and home ownership levels in Sydney were high. Workers could earn good wages and because of mortgages provided through building societies, could venture into home ownership, although this was not prevalent in suburbs like Redfern, Waterloo or Alexandria. And the city's population found no favour with the snobbish and puritanical Beatrice Webb, who noted that

Sydney, in spite of its exquisite harbour and lovely Botanical Gardens, is a crude chaotic place. It is seemingly inhabited by a lower middle-class population suddenly enriched. [21]

But economic fluctuations could take their toll: when economic activity began to decline in the 1880s and government spending on public works fell from £5.2 million in 1885 to £2.1 million in 1888, some 15,000 men were thrown out of employment, forcing the government to start relief work programs. [22] And women were increasingly moving out of the slavery of domestic service into the relative freedom of factory work.

Feeding, clothing, transporting and entertaining the city's expanding population were growth industries. Apart from their local customers, city retailers developed strong mail-order businesses selling to rural folk. Oxford Street and George Street in the city and King Street in Newtown were dominant 'high streets', serving not only their local communities but also other nearby suburbs. Waves of immigration brought some ethnic diversity to a predominantly English colony, and parts of the city reflected this: lower Oxford Street (previously the Old South Head Road) was home to dozens of different cultures and languages, its inhabitants bringing their skills and tastes to the new world. [media]The Irish ran the pubs, the Swiss and Germans were prominent in the precision industries of watchmaking and opticals, Greek and Italian names stood out above fishmongers, oyster bars and greengrocers. The Spanish and Portuguese had their bodegas and delicatessens, and celebrated masses in their own languages at local churches, while the Chinese street vendors hawked their wares around the local suburban streets. Sydneysiders were continually being introduced to new 'foreign' products.

Getting around the spreading city was facilitated by an expanding horse bus system: by 1894, there were 68 horse-bus services operating in Sydney, adding to the train network and soon to be joined by an expanding tram system, initially horse-drawn but later powered by steam. Lacking easy transport connections, the north shore was slower to develop, although Manly had started its long road to becoming one of Sydney's more famous tourist destinations.

The city's hinterland

While the urban working classes of Sydney were able to pursue radical demands for more democratic political representation, those who lived in the more scattered communities on the fringes of the Cumberland Plain sowed, tilled and harvested, herded and husbanded: the hinterland that supplied the growing metropolis with its everyday food needs. [media]The Parramatta River played a crucial role in the economic development of greater Sydney, as industries increasingly used the river for access to their sites. As the pastoral industry expanded in the late nineteenth century, it needed fencing, and a galvanised iron and wire-netting works began on a riverside block in Camellia in 1884. As more rail spurs went in, industrial development accelerated along the riverbank, with a wide range of new industries appearing. Some benefitted from their proximity to nearby raw material suppliers: a tannery opened in 1895 on land adjacent to the Sandown Meat Co, purchasing and tanning the skins from the animals slaughtered nearby. [23]

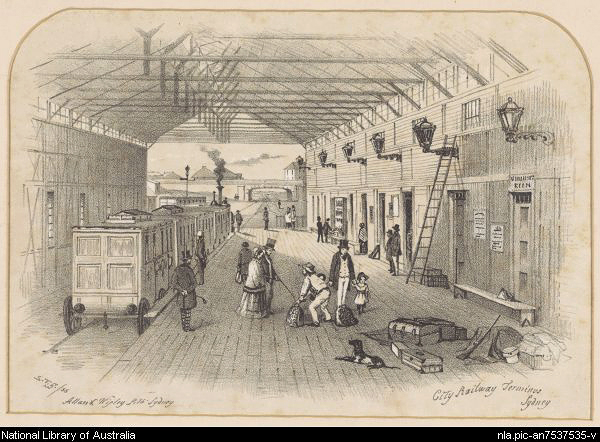

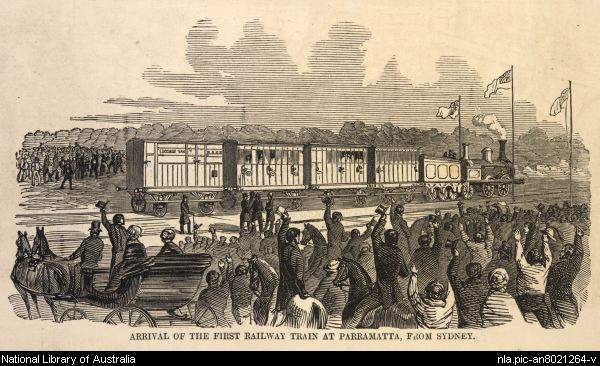

[media]At Parramatta itself, the arrival of the railway in the 1850s moved the centre away from George Street and river wharf, to Church Street and the railway station. Major stores and businesses began to realign themselves, and industrial businesses were set up, including blacksmiths, which later turned into engineering firms; there were also millers, tanneries, brick kilns and tweed mills. Parramatta's emerging role as a retail centre was reflected in the number of major bank branches established there. [media]Parramatta also experienced its own suburbanisation boom from the 1870s, as satellite towns developed in areas such as Harris Park and Granville.

On the far reaches of the Cumberland Plain, in the agricultural Penrith and St Marys districts, the Great Western Road and, later, the railway gave direct access to city markets, and this enabled other industries besides agriculture. Quarrying developed early, with gravel and sand extraction beginning at Emu Plains as early as the 1880s.

As French visitor Edmond Marin la Meslée perceptively noted, Sydney's

whole development flowed naturally from the immense resources of its hinterland, for which it will always remain the chief port. [24]

Sustained growth, population increase from immigration, and capital inflow were clearly correlated: land, labour, capital and entrepreneurship created a heady mix in the Antipodean metropolis-to-be, in an era known as 'the long boom'. But once again, over-expansion led to a depression.

Depression in the nineties

The closing decades of the nineteenth century were dire times for Sydney. Drought in the mid-1880s continued well into the 1890s, causing increasing rural unemployment. Unemployed rural workers moved to Sydney looking for work, with disastrous effects on the city's economy, already suffering from a downturn in manufacturing and construction industry by the late 1880s. The colonial government commissioned new public works, such as extending the tramline from Waverley to Randwick, and setting up the Kurnell industrial site, as a way of soaking up the unemployed.

Sydney's problems were exacerbated from 1890 by the collapse in London of Baring Bros bank, which led to turmoil in world capital markets. Capital flows to borrowers dried up, with early effects on banks and other financial institutions that were heavily geared with debt. By late 1891, two Sydney banks had failed. Subsequent industrial unrest – the shearers' strike and the maritime strike – added to the sense of foreboding, as other financial institutions started to fail. The actions of overconfident, negligent or criminal directors helped send the economy into a downward spiral. Early in 1892 there was a run on the Savings Bank of New South Wales, and even though the government stepped in to support the bank, the crisis continued. Over the following year, other lending institutions, including several 'land banks' and some building societies, failed. In May 1893, the city's largest bank, the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, suspended payments, and one-third of its deposits were compulsorily converted into equity (as shares) in the bank. Other banks had their deposits frozen.

All this had a disastrous effect on the lives of Sydneysiders. Unemployment rose and family incomes sank; homelessness increased; large numbers of people were forced to 'sleep out' in the city's parks and on its beaches. The Domain provided a haven for many: there were literally hundreds of homeless men – the 'hobos' and 'sundowners' –

who nightly use the niches and crevices of the rocks as their dormitories, from the dim recesses of which they draw forth their 'bed-clothes', consisting of old newspapers and wrappers. [25]

By mid-1893, Sydney's economy was at its lowest ebb, and there was little confidence in the system. By late 1895, 14 of Australia's trading banks had collapsed, although Sydney-based banks did better because of government activity. By the end of the following year, the 'financial crisis' was over, and the London capital market was lending worldwide again, with new loans to New South Wales written from 1895. However, the onset of a new drought that continued until 1903 meant that the economy did not recover until towards the end of the first decade of the twentieth century.

Recovery through wool and trade

The end of the drought and rising wool prices brought immense benefits to Sydney's commercial life. Wool accounted for nearly half of the value of the colony's domestic exports, and Coghlan noted in 1900 that

buyers from Continental Europe increasingly come to Sydney for the purpose of attending the wool sales. [26]

Twenty years earlier those sales would have been held in London. The heavy capital expenditure in infrastructure works like rail links and port facilities made over the last years of the long boom now brought benefits, as the wool clip went directly to Sydney's wharves and thence to Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Austria. New technological developments in refrigeration and in port facilities also meant that export markets could be expanded, with benefits to the colony's major port: new exports, of butter and frozen meat, from the second half of the 1890s helped Sydney's economic recovery.

The American sociologist Adna Ferrin Weber commented at the time on Australia's unique urban pattern, with an unusually high proportion of population living in the cities. One cost of this was continuing high levels of urban unemployment after depressions. In 1898 the colonial government had again started public works programs in the city, employing 2000 men to scrape and paint the iron railings of Hyde and Centennial parks. [27] Other government interventions led to improved economic prospects. [media]New ideas which greatly improved the economic prospects, and aesthetics, of parts of Sydney arose from such diverse sources as the impact of the plague of 1900, the 'City Beautiful' movement, slum clearance plans, and a 1908 Royal Commission for the Improvement of Sydney and its Suburbs. The plague gave the government the excuse to dramatically restructure Sydney's port facilities. The Sydney Harbour Trust was established to construct new up-to-date wharf facilities, and rebuild Circular Quay, all in the pursuit of scientific and technical excellence.

A retailing revolution which had started in Paris in the 1850s also reached Sydney, with new 'department stores' appearing, many in lower Oxford Street – Mark Foy's, Winn's, Buckingham's, Edward Arnold's and Brasch's – and these stores drew many women into the workforce. Destination shopping had arrived, greatly facilitated by the advent of steam trams. [media]The trams also led to a new burst of suburbanisation: Sydney was transformed from a 'walking city' to a 'public transport' city, as population spread from the old rented inner-city terrace houses to the new, often owner-occupied, detached cottages, along the skeleton of the rail and tram lines.

Many of these new suburbanites were members of the lower middle classes or the more secure members of the working classes, largely tradespersons or government employees. Some new suburbs had distinct religious flavours. The north shore, the St George district and the Sutherland Shire were largely Protestant, a cultural factor which had real economic consequences. In all the suburbs of the Sutherland Shire there were a mere handful of hotels, while the small inner-city neighbourhood of Glebe had almost 20. Growing concerns about alcohol consumption led to the emergence of 'coffee palaces' and temperance hotels, new businesses somewhat at odds with the city's hard-living reputation.

The possibility of federation of the colonies heightened concerns about the economic impact of a protectionist national government on free-trade Sydney. Sydney's economy was heavily dependent on its foreign trade: the value of goods passing through the port had risen from £400,000 in 1825 to £52 million in 1898. [28] As one observer noted in the early 1880s,

one would suppose that a better class of things would be obtainable in free-trade Sydney than in protected Melbourne. [29]

But federation did bring some benefits to Sydney's economy: the introduction of uniform customs tariffs which gave protection meant new manufacturing industries were able to start in the city where labour force and market were in close proximity, and an Australia-wide market for Sydney producers emerged.

World War I brought a brief pause to the city's economic development, although some import replacement industries emerged when imports from Europe were interrupted.

The interwar years

The interwar years are often called the 'sad, lost years' in Sydney's history. Even as thousands of soldiers returned from the theatres of war, looking for work and a return to normalcy, the great influenza epidemic of 1919–1920 brought thousands more deaths to the city. In the decades that followed, economic uncertainty turned to catastrophe in the Great Depression.

In 1921, metropolitan Sydney held 43 per cent of the state's population and 45 per cent of its jobs, while in 1947, when the city contained just over 50 per cent of the state's population, it had 53 per cent of the state's jobs. While commerce continued as the backbone of Sydney's economic activity, manufacturing was becoming the largest employer. In the interwar years, the city and inner suburbs continued to be the heart of Sydney's manufacturing, with industrial concentration notable in Alexandria, followed by Waterloo, Redfern, Marrickville and Balmain. [30] But there was expansion and diversification, with an ongoing trend of switching from labour-intensive forms of production to new automated technologies.

The impact of new technologies

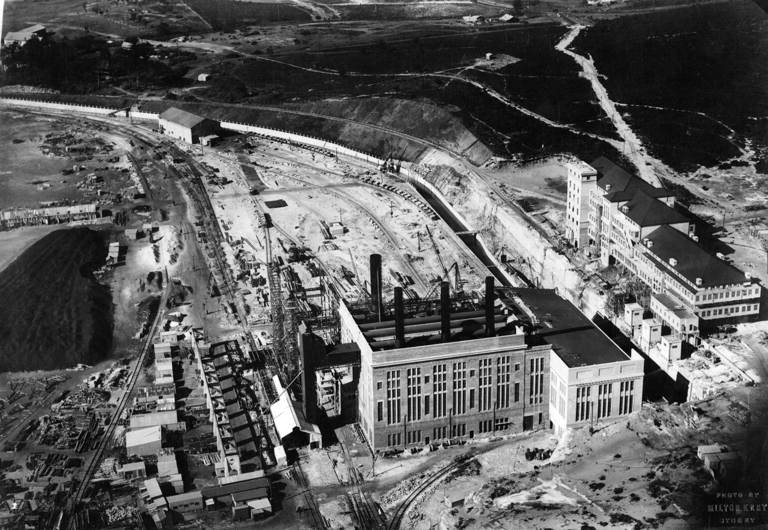

While it was still largely a steam-driven economy, gas and electricity were making inroads. [31] The electrification of the ever-expanding tram network had started decades before, and the City Council had been providing electricity to both private customers and suburban councils since 1904, when the Pyrmont Power Station had gone on line. In the 1920s, there was an explosion in domestic electricity consumption as Sydneysiders enthusiastically acquired the new-fangled electrical gadgets – irons and vacuum cleaners, and the ubiquitous electric jug. [media]Growing demand led to the building of the Bunnerong Power station near La Perouse between 1926 and 1929. All of this electrification was largely financed by British loans, and the ever-increasing demand led to the creation of Sydney County Council in 1935, to generate and supply electricity for the metropolis.

Electrification was important for the new industries, and the rail lines, electrified from the 1920s, played a critical role in allowing gradual industrial development outside the old inner-city industrial suburbs. Further industrial developments, including new chemical and rubber companies, appeared along the Parramatta River, with access to water, rail and road transport and a nearby labour market.

In the immediate post-World War I period, industries that used local raw materials and had local markets maintained their cost advantage due to the 'tyranny of distance'. Industries that fed, clothed and housed the city's population did not have to worry about competition from imports and grew steadily. Market gardens from Botany to the Hawkesbury provided food, later facilitated by a weir built on the Warragamba River in the late 1930s to improve the city's water supply. Government decided to move into areas of production previously the domain of private enterprise, such as bricks and roof tiles, to ensure their continuance. [32]

The entertainment industry crossed new frontiers with radio and the cinema, introducing new spending patterns for those who could afford it. Population growth in metropolitan Sydney – from just under 900,000 in 1921 to 1.337 million in 1941 – underpinned the expansion of industries during these years, but also put great demands on the infrastructure that served the city's commerce. The city needed improvements in power generation, its rail system, and its roads, increasingly crowded because of the growing use of motor lorries. [33]

When peace was declared in 1918, authorities had expected that 'a return in some measure to pre-war conditions would follow'. [34] Suburban expansion did continue, with Sydney's tram and ferry networks reaching their greatest extents in the early 1920s, allowing new suburbs to be opened up. And the 1920s, despite their reputation as boom times of jazz and cocktails, were in reality far more mixed. Food production that had expanded during the war years created oversupply, and despite a decline in wheat export prices, volumes held up Sydney's port activities. There were economic fluctuations, and unemployment levels often rose dramatically. During that decade, the Domain once again provided a haven for the homeless. The Salvation Army noted that even in 1923 there were so many homeless men living there that they had supplied over 17,000 meals to them in only 10 weeks. [35]

The depression of the 1930s

Into this already volatile mix came the October 1929 Wall Street stock market crash, setting off a worldwide depression. In Sydney, factories found demand falling even further, and began closing. Output fell almost 10 per cent in 1929–30 and another 30 per cent in 1930–31. Workers were laid off, and the state's unemployment level rose to 21 per cent by mid-1930 and almost 32 per cent in mid-1932. The Depression brought widespread misery. [media]As the economy faltered, and more and more people lost their jobs and were evicted from their homes for falling behind with rent, shanty towns appeared around Sydney, as at La Perouse and Brighton-le-Sands. In the Domain, villages of hessian and frame 'tents' appeared, and the unemployed and homeless gathered around campfires at night. This phenomenon was poignantly described in Christina Stead's novel For Love Alone. In such circumstances, it is little wonder that some 'escapist' industries flourished: breweries did well, and in the inner city, the working-class suburb of Darlinghurst became renowned for the prostitution and drug trades, earning it the soubriquets of Razorhurst, Cocainehurst, and Goldenhurst.

[media]Arguments over the appropriate economic policies to pursue to cushion the effects on the population hindered recovery, and led to political upheaval. Premier Jack Lang was sacked over his radical plans for greater deficit spending and debt interest deferral, policies that were greatly at odds with the economic conventions of the time. But massive public spending on the Harbour Bridge, the city underground rail system, and the power stations all helped to see the city and its inhabitants through the tough times. Despite new industries appearing in the suburbs, it is unclear whether the city's economy was in recovery mode at all during the later 1930s. It has been argued that recovery may have commenced in 1933, due partly to improved economic conditions and partly to changes in tariff policy designed to protect jobs by countering import flow, allowing manufacturing to grow. But it was World War II, and the mobilisation of labour and resources for the nation's survival, that got the economy moving rapidly again, and alerted the authorities to the virtues of a more managed economy.

Postwar changes

In the months prior to the war, the state's economic conditions had begun to worsen again after a period of possible recovery. Wartime production soon began to reverse this, and many women were drawn into the city's workforce, as men went off to the armed forces. [media]Indeed, during the war, the city's economy hummed, and new infrastructure, such as the Captain Cook Graving Dock, was a welcome addition to the city's economy. Novelist Kylie Tennant has described the port's atmosphere:

Docks boiled with activity, the arc lights blazing, cargo swinging into the holds of ships. Loaded lorries bumped down to the wharves. Trucks squealed through the dark shunting goods yards. All night long the whistling and squealing would deny the pretence of sleep that lay over the city, and not until two, three, four in the morning would there come that deadline of stillness that heralded the paper trucks, the milk and bread of a new day. [36]

But the war eventually ended, and the city returned to 'normal'.

[media]One significant feature of Sydney's postwar development was the massive growth in its population, from 1.8 million in 1951 to 3.2 million in 1981. The city spread from the beaches to the lower Blue Mountains, from Broken Bay to Port Hacking, growing to almost 70 kilometres wide east to west and 60 kilometres north to south. Parramatta, once an outlying settlement, now lies close to the demographic centre of Sydney.

Another important feature of the postwar period was large-scale immigration, bringing in workers for factories and major public works programs. The city's ethnic mix began a process of gradual but irrevocable change. [media]From the late 1940s, immigration was mostly from Europe, but as the White Australia Policy was gradually abandoned, and especially after 1971, large numbers of non-European migrants began to make their homes in Sydney. The sources of this influx have changed over the decades, from Europe to Asia and the Middle East, and now include permanent migrants, overseas students, and refugees. By the end of the twentieth century, just over 30 per cent of Sydney's population was born outside Australia. If those with one or both parents born outside Australia are added, the number rises to over 50 per cent.

Many of these migrants initially settled in the inner city, near jobs. But they were soon joined there by other groups, looking for cheap rent. Some were students, but there were also the new 'urbanites', mainly young people fleeing from suburbia, as well as others who came to the inner city looking for a cosmopolitan alternative to the suburban life. [37] The new demographics were to have an important impact.

Growth industries

Moving people or goods around this expanding city was increasingly a problem. Manufacturing industry shifted from the older inner suburbs to the fringes, a move made possible by the increasing use of motor vehicles, which freed industry from its traditional reliance on rail or water-borne transport. It was the car and the truck that 'allowed many industries to move from the inner city to the outer suburbs'. [38] On [media]the other hand, the 'motor vehicle mentality' had disastrous effects on Sydney's development, with the expanding western suburbs poorly served by public transport. The decision to replace trams with buses in the early 1960s exacerbated the city's transport problems. Even so, home ownership levels increased, even in the west.

Postwar population growth and spread necessitated the expansion of higher education facilities for Sydney. Lessons from the war years about keeping abreast with new developments in science and technology, led to the establishment of what became the University of New South Wales (formerly the New South Wales University of Technology), incorporated in 1949, followed by Macquarie University in North Ryde in 1967, and the University of Western Sydney in 1989, this latter building on the existing Hawkesbury Agricultural College and Nepean College of Advanced Education. The greater number of students who could be trained through these institutions gave a major boost to the skills of Sydney's workforce – as well as stimulating initial demand, as in building and construction, and later in education and local service industries.

New city centres and gentrification

In the late 1960s, Parramatta and Campbelltown were nominated as other major city centres for the rapidly expanding western Sydney region. Parramatta has consolidated its role as Sydney's second central business district in the geographic heart of the city, and is now a focal point for business, shopping and entertainment for western Sydney, and a key transport hub. Campbelltown has become a significant centre in the city's south-west, while north of the harbour both North Sydney and Chatswood have become high-rise nodes.

[media]Population spread, and the increasing availability of the motor car, also led to the appearance of the suburban shopping mall from the 1960s, where population densities were greatest: initially in Sydney's south-west, at Miranda, Bankstown and Roselands, and in the north, at Top Ryde and Brookvale. While these new developments undoubtedly made life easier for local shoppers, there were side effects – the great department stores that had dominated the central business district for decades began to disappear, and shops on nearby local high streets lost custom to the new giants. Old family businesses might disappear, but new job opportunities opened up for younger Sydneysiders moving into the workforce.

The Sydney central business district experienced a major property boom in the period from 1968 to 1974, largely due to the prosperity generated by a mining boom, as Sydney once again 'financed' a major export industry. [media]This prosperity fed Sydney's property market, [39] with new buildings in the CBD reaching ever upwards. The early 1970s was a time when property developers had their eyes on Sydney:

Entire suburbs and precincts such as Woolloomooloo, Victoria Street in Potts point, Paddington, Millers Point and The Rocks were faced with modification and extinction. [40]

But there were unusual forces working to prevent the destruction of historic Sydney. By the 1970s and early 1980s, 'yuppies' were buying into the suburbs of Darlinghurst, Surry Hills, and East Sydney, and the process of gentrification was well under way, bringing new life back into what had long been considered 'slum' areas of Sydney. The newcomers brought skills that would ultimately benefit both the areas they moved to and the city itself: they helped form dozens of resident action groups willing to combine with militant unions or professional organisations to further their cause of saving their local environment and protecting their amenity. [media]In support of such groups, Green Bans imposed by the Builders Labourers Federation forced a halt to some of the worst excesses of the developers, despite the apparent conflict with workers' own interests.

Some of the ethnic groups who had long been in the inner-city areas stayed – Chinatown remained, as did the 'Spanish Quarter' of lower Liverpool Street, and 'Little Italy' in both Stanley Street in East Sydney and Leichhardt. Other immigrant groups took advantage of good prices for their inner-city terrace housing and moved further out: some outer suburbs developed their own strong ethnic characters. Thus Cabramatta has a strong Vietnamese identity, Lakemba is dominated by Lebanese and Muslim communities, while the Ryde and Chatswood areas now have a strong Chinese presence. Other ethnic groups have tended to congregate in various suburbs for family and community reasons, and these have all developed identities that draw shoppers from across the city and beyond.

Sydney's urban future

The city's continuing expansion has, over time, led to many plans being devised either to facilitate the spread, or to stop it and create a denser city, better able to use existing infrastructure. In the immediate postwar period, a green belt and decentralisation with distant 'growth centres' was the desired objective; urban consolidation has become the catch-phrase of the early twenty-first century.

Urban consolidation is a policy that has clear economic implications for the city. As Sydney's ageing infrastructure began to crumble under population pressure, governments forced through policies that encouraged increased densities around existing transport nodes. [media]New ways of financing roads and motorways were explored. But these brought costs: travel became more expensive, and rising petrol prices led to many Sydneysiders rethinking ways to get to work. Unfortunately, public transport, after decades of replacement neglect, is unable to cope with peak hour population movements. Gridlock, in the city streets and on the major motorways, brings its own economic costs to the city.

Traffic issues also affect other infrastructure in Sydney. Constraints on physical wharf capacity, environmental concerns and the inability of huge modern trucks to navigate Sydney's dockside streets have led to the near-disappearance of commercial shipping from Port Jackson. The massive expansion of containerised maritime trade now comes through Port Botany, the city's main sea gateway, although this affects access and amenity for the surrounding suburbs.

Sydney's airports have traffic problems too. Kingsford Smith International airport at Mascot has been in operation since the 1920s, and there are pressures to allow more flights outside curfew times, and also to expand airports at both Bankstown and Camden, all major growth nodes, with many subsidiary industries located nearby. The air base at Richmond, on the other hand, is still operational for the Royal Australian Air Force.

A global city

As the state government proudly proclaims, 'Sydney is Australia's principal city, generating 23 per cent of the nation's value added wealth. It is Australia's largest regional economy'. It goes on:

With 30 per cent of national employment in financial and business services, and nearly half of Australia and New Zealand's top 500 companies based here, Sydney has earned its reputation as the preferred location for businesses in the Asia Pacific region. More than 60 percent of Asia Pacific regional headquarters established by multinational companies choose to reside here. [41]

Sydney's commercial underpinnings continue to support its economy and its 'lifestyle': as one historian has noted,

by the end of the twentieth century, the production and consumption of high-quality produce and fine foods had become a major business … Sydney chefs and restaurants have developed a world-wide reputation for their care and creativity. [42]

From the late twentieth century, there has been ongoing change in the economy of metropolitan Sydney, due to both internal and external factors. With reduced tariff protection, a range of urban manufacturing industries have gone, while the global economic crisis of 2008–09 led to job losses in various sectors, from retailing to finance, on top of those in manufacturing. And there has been an increased 'casualisation' of the workforce. At the same time, with the rise of Sydney as a financial capital in the Asia-Pacific area, property interests have grown more powerful. Part of Sydney's economic strength comes from its continuing commerce functions, with imports and exports now routed through Port Botany and Wollongong, rather than Port Jackson.

Tourism[media] is now a major industry. Sydney has become a popular tourist destination, particularly for Asian tourists. In 1995, just over 2 million foreign tourists visited Sydney (and 6 million visits were made by Australians). [43] It probably started with the Bicentennial celebrations of 1988 or the Olympics in 2000, which possibly generated some economic benefit to the city, although shifting exchange rates have encouraged inbound, and discouraged outbound, tourists from the mid-1980s onwards. The Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras attracts overseas and interstate visitors who spend money shopping, dining out, and on accommodation, and is now seen as a major money earner, reputed to generate more than $30 million of direct economic benefit each year, with the added benefit of being an international showcase of the city's diversity. [44] Successive state governments have argued that the spending power of thousands of visitors can be felt in Sydney events such as the Rugby League World Cup, the FIFA Congress, the V8 car races at Homebush, or the Asian and Pacific fashion festivals held in Sydney. Events NSW [media]has been established to encourage major events to come to Sydney, because of the economic stimulus they could bring: it has become an 'events-driven' city. [45]

Limits to growth

Changing orthodoxies in economic thinking have also affected Sydney. From the late 1970s a neo-classical idea known generally as 'monetarism' was revived as a response to the new phenomenon of 'stagflation' – a stagnant economy with high levels of both unemployment and inflation. 'Monetarist' policies became popular among treasury officials and politicians over the following decades, concentrating on monetary policy and debt reduction as economic fundamentals, ignoring decades of experience of Keynesian ideas about economic cycles and counter-cyclical spending.

The simplistic idea that all debt is bad, and that governments should always aim for a surplus, took hold in the final decades of the twentieth century, with disastrous consequences: it almost seemed a reversion to the mercantilist ideas of centuries ago. The state government abandoned the overseas borrowing that had been used to build infrastructure for a century and a half, with the result that in the first decade of the twenty-first century, infrastructure – ports, public transport, energy supply, hospitals and schools – began to crumble under the weight of usage and lack of maintenance or replacement. The ultimate 'logic' of the neo-liberal program has been the hollowing out of the public sphere of the economy and society. One ironic result of the world financial crisis of 2008–09 has been that Keynesian ideas of counter-cyclical spending, financed by public debt, are now becoming 'acceptable' again.

Today, there are several distinct economic regions within metropolitan Sydney. One major development, fostered by the state government, has been the creation of the 'global economic corridor' – the concentration of linked jobs and gateway infrastructure from Macquarie Park in the north-west through Chatswood, St Leonards, North Sydney and the central business district to Sydney Airport and Port Botany. It is now a critical part of Sydney's economy, and new technologies are an integral part of many industries in this corridor.

But around this central core are other regions. To the south is Sutherland Shire, predominantly a dormitory suburb for the metropolitan area, with over 65 per cent of its workforce of 105,000 people commuting out of the region for work, mostly in the Sydney central business district and nearby regional centres, since the area itself has no dominant industry.

On the western part of the Cumberland Plain is Greater Western Sydney, which stretches over nearly 9,000 square kilometres of residential, industrial and rural land. [46] The diversity of the region is reflected in its rapidly expanding economy. It is estimated that the Greater Western Sydney Region generated $71 billion in gross regional product in 2004–05, and is, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the third largest regional economy in Australia. [47] But plans to build new growth centres in the south-west ignore the fact that the area is an acknowledged pollution sink: the nearby Blue Mountains stop winds from dispersing smog- and chemical-laden air that collects there. Health problems, with their own economic costs, will loom in the future if planned development goes ahead.

Sydney's eastern suburbs, covering an area from the beaches of Sydney Harbour in the north to the shores of Botany Bay in the south, have Sydney's second-highest population density. Around 48 per cent of the region's population lives in apartments, townhouses and other medium density dwellings, [48] a far cry from the suburban quarter-acre that was once seen as 'the Australian dream'. North of the harbour lie several distinct regions, from the semi-rural and food-producing areas of the north-west, through the tip of the 'global economic corridor', to the laid-back cultures of the northern beaches.

A 'black economy' – mainly drugs, gambling and prostitution, but also other sources of undeclared income such as parts of the service and building industries – also exists in Sydney. According to the Taxpayers' Research Foundation, Australians are now failing to declare more than $100 billion a year in income to the Tax Office – an estimated 15 per cent of gross domestic product, [49] and Sydney's share is extensive.

Emerald city?

With growing unemployment, mortgage defaults, and a global financial crisis, life is not all glamour and glitz in Sydney: it has the dubious distinction of being, of all Australian cities, 'more expensive on almost every count: housing, rent, food, eating out or transport', [50] in a time of growing unemployment and deteriorating living standards. And the city faces problems associated with water shortages, greenhouse gas emissions and global warming, [51] to name but a few, on top of its crumbling infrastructure and a state government seemingly unable to deal positively with any of the issues confronting it.

[media]But as has so often happened in the past, the residents of Sydney – the 'Emerald City' as described by playwright David Williamson – ignore the doomsayers: even with its ever-apparent faults, in the latter years of the first decade of the twenty-first century its population continues to grow, many obviously believing those advertising agency claims that Sydney is 'the world's most desirable city'. [52]

References

Graeme Aplin (ed), A Difficult Infant: Sydney before Macquarie, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1988

SJ Butlin, Foundations of the Australian Monetary System, 1788–1851, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1953

NG Butlin, Investment in Australian economic development, 1861–1900, Department of Economic History, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, 1972

TA Coghlan, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales 1895–6, Government Printer, Sydney, 1897

MT Daly, Sydney boom, Sydney bust: the city and its property market, 1850–1981, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1982

Barrie Dyster, Servant & master: building and running the grand houses of Sydney 1788–1850,

New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1989

Barrie Dyster and David Meredith, Australia in the global economy: continuity and change, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1999

Shirley Fitzgerald, Sydney: a story of a city, City of Sydney, Sydney, 1999

Shirley Fitzgerald, Chippendale: beneath the factory wall, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2009

Shirley Fitzgerald and Hilary Golder, Pyrmont and Ultimo: under siege, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2009

RV Jackson, Australian economic development in the nineteenth century, ANU Press, Canberra, 1977

Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: city of suburbs; New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1987

Max Kelly (ed), Nineteenth-century Sydney: Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1978

Bev Kingston, Basket, bag and trolley: a history of shopping in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1994

Bev Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006

Macquarie University Library, Journeys through time, at http://www.lib.mq.edu.au/all/journeys/related/73rd.html

Jill Roe (ed), Twentieth century Sydney: studies in urban and social history, Hale & Iremonger, 1980

WA Sinclair, Australian economic development in the twentieth century, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1970

Peter Spearritt, Sydney's century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1999

Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, London, Elliot Stock, 1883

Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999

Garry Wotherspoon (ed), Sydney's transport: studies in urban history, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1983

Notes

[1] Library of Economics and Liberty, Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, Laura LaHaye, 'Mercantilism', http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Mercantilism.html, viewed August 2009

[2] SJ Butlin, Foundations of the Australian Monetary System 1788–1851, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1953

[3] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999

[4] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999

[5] SJ Butlin, Foundations of the Australian Monetary System 1788–1851, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1953

[6] JW McCarty, 'The Staple Approach in Australian Economic History', Business Archives and History, vol IV, no 1, February 1964

[7] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999, pp 82–3

[8] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999, p 82

[9] Terry Irving, The southern tree of liberty: the democratic movement in New South Wales before 1856, Federation Press, Annandale, 2006; Peter Cochrane, Colonial ambition : foundations of Australian democracy, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2006

[10] Norman Edwards, 'The Genesis of the Sydney Central Business District, 1788–1856', in M Kelly (ed), Nineteenth-Century Sydney: Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1978

[11] Barrie Dyster, Servant & master: building and running the grand houses of Sydney 1788–1850, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1989

[12] Bev Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006, p 97

[13] G Wotherspoon, 'The "Sydney Interest" and the Rail 1860–1900', in M Kelly (ed), Nineteenth century Sydney: Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1978

[14] TA Coghlan, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales 1895–6, Government Printer, Sydney, 1897, p719

[15] NG Butlin, Investment in Australian economic development, 1861–1900, Department of Economic History, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, 1972

[16] Hilary Golder, Politics, patronage, and public works: the administration of New South Wales, University of New South Wales, Press, Kensington, 2005

[17] Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, Elliot Stock, London, 1883, p 23

[18] Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, Elliot Stock, London, 1883, p 23

[19] AJ Mayne, Representing the slum: popular journalism in a late nineteenth-century city, History Department, University of Melbourne, 1991, p 33; Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: city of suburbs, New South Wales University Press, Kensington, 1987

[20] Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, Elliot Stock, London, 1883, p 20

[21] Beatrice Webb, quoted in AG Austin (ed), The Webb's Australian Diary 1898, Melbourne, Pitman & Sons Ltd, 1965, p 22

[22] TA Coghlan, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales 1895–6, Government Printer, Sydney, 1897, p 719

[23] James Jervis, Parramatta: Cradle City of Australia, Parramatta City Council, Parramatta NSW, 1961, p 183

[24] Edmond Marin la Meslée, The new Australia, translated and edited by Russel Ward, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1973

[25] H Furniss, Australian sketches made on tour, Ward, Lock, London, 1899

[26] TA Coghlan, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales 1898–9, Government Printer, Sydney, 1900, p 139

[27] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999

[28] TA Coghlan, The Wealth and Progress of New South Wales 1898–9, Government Printer, Sydney, 1900, p 123

[29] Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, Elliot Stock, London, 1883, p 199

[30] P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2000

[31] Official Year Book of New South Wales, 1920, NSW Government Printer, Sydney, 1921, p 332

[32] Official Year Book of New South Wales, 1920, NSW Government Printer, Sydney, 1921, p 330

[33] P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2000

[34] Official Year Book of New South Wales, 1920, NSW Government Printer, Sydney, 1921, p 22

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 June 1923

[36] Kylie Tennant, Tell Morning This, Pacific Books, Sydney, 1967, p 28

[37] A Jakubowicz, 'The City Game: Urban Ideology and Social Conflict', in D Edgar (ed), Social Change in Australia, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1974, p 336

[38] P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2000, p 269

[39] MT Daly, Sydney boom, Sydney bust: the city and its property market, 1850–1981, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1982

[40] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999, p 195

[41] NSW Government Metropolitan Strategy, Economy and Employment, http://www.metrostrategy.nsw.gov.au/dev/ViewPage.action?siteNodeId=52&languageId=1&contentId=-1, viewed August 2009

[42] Bev Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006, p241

[43] Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999, p201

[44] 'NSW Govt to sponsor Sydney Mardi Gras', Inside Retailing, 2 October 2008, http://www.insideretailing.com.au/Default.aspx?articleId=3735&articleType=ArticleView&tabid=53, viewed August 2009

[45] Bev Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006, final chapter

[46] Department of State and Regional Development website, 'Business in Regional New South Wales – Western Sydney', http://www.business.nsw.gov.au/region/profiles/westernsydney.htm, viewed August 2009

[47] Department of State and Regional Development website, 'Business in Regional New South Wales – Western Sydney', http://www.business.nsw.gov.au/region/profiles/westernsydney.htm, viewed August 2009

[48] Russ Grayson, 'Profligacy, greed or simply don't care?' in Pacific Edge, 13 October 2007, available onhttp://www.isa.org.usyd.edu.au/about/PE_Ecological-footprint_Eastern%20Suburbs_13-10-07.pdf, viewed August 2009

[49] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 2003; 21 May 2009

[50] P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2000, p 263

[51] Bev Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006, p 251

[52] Austrade website, Tim Harcourt, 'And the winner is … Sydney (again)', http://www.austrade.gov.au/The-winner-is-Sydney-again/default.aspx, viewed August 2009

.