The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Windmills of Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Windmills

[media]The magnificent roof of the Sydney Opera House is famous throughout the world for its 'sails' and for providing Sydney with such an iconic skyline. Yet long before the Opera House was built, sails of a different kind dotted the Sydney skyscape. In the late eighteenth century, and well into the nineteenth century, the tallest structures around Sydney Cove were windmills. They left few physical remains, yet their presence left a lasting legacy in early colonial landscape art and the minds and hearts of many contemporaries.

In the early days of white settlement, food shortage was a constant and pressing problem. The First Fleet landed with 40 hand-powered iron mills but they proved hard work and were generally unsatisfactory as they wore out easily. A windmill was urgently needed to grind grain for the fledgling community and numerous and regular requests for a mill to be sent out were despatched to London. Eventually, parts for a windmill were shipped out from England and arrived with Governor John Hunter in September 1795.

Government windmills

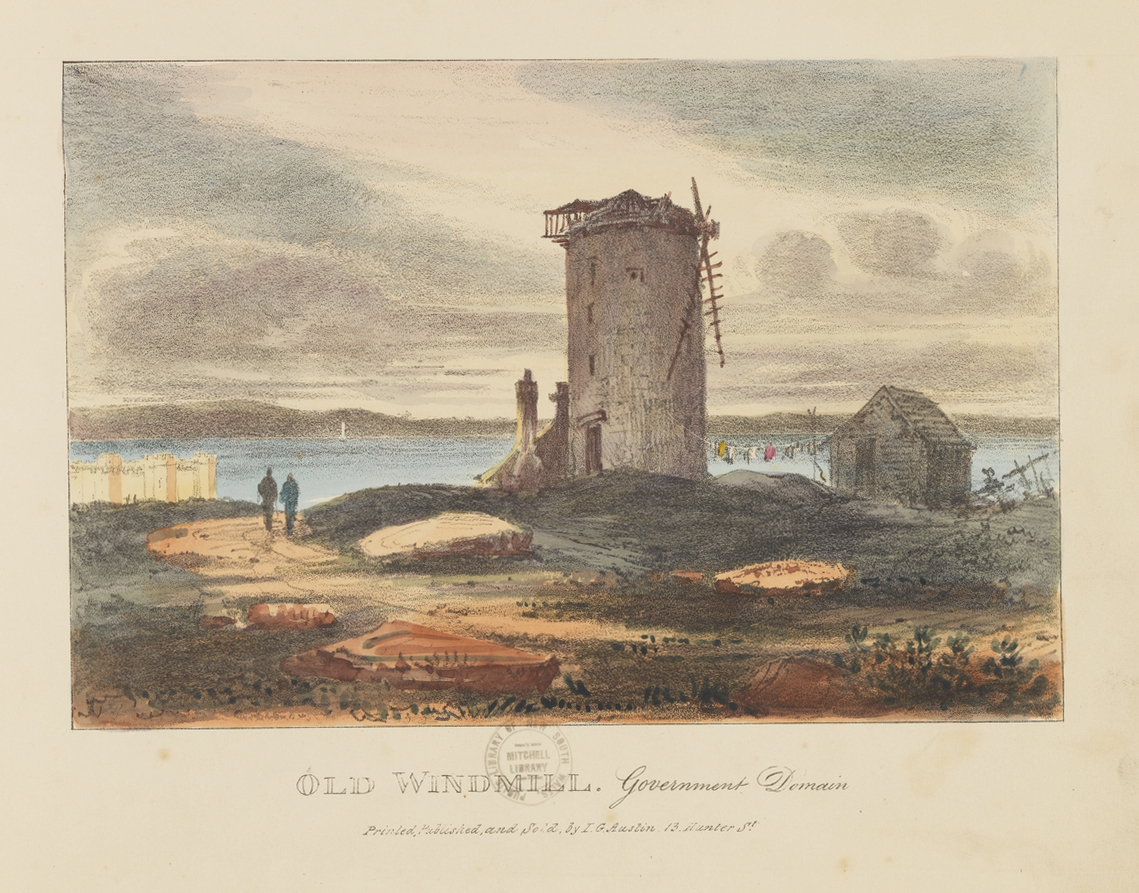

[media]The early colonial government built three windmills in Sydney. The first windmill was built on Flagstaff Hill (now Observatory Hill, but also known as Windmill Hill) in 1797. In February 1797 David Collins recorded in his journal that

the windmill being nearly finished at the commencement of this month, it was tried with only two of its sails; when it ground, with one pair of stones, a bushel of wheat in ten minutes, and considering the immense weight of the wood-work, its motion was found to be easy and convenient. [1]

[media]Despite this progress and Governor Hunter's boast to the Colonial Office in London that the manpower in the colony was capable of building 'a strong substantial and well-built windmill with a stone tower, which will last for two hundred years', the mill soon fell into disrepair and from about 1810 the stone tower stood without sweeps for many years. [2] In January 1798, the construction of a second windmill commenced on the site where Clarence Street now crosses the top of Grosvenor Street. [3] Hunter's rather optimistic 200-year assertion was again dashed to pieces, together with the windmill, when a violent three-day storm ravaged Sydney in June 1799. According to David Collins,

…the weather became very tempestuous and continued for three days blowing a heavy gale from the southward, attended with a deluge of rain; by which several buildings belonging to Government, which had been erected with great labour were much damaged; among others, was unfortunately the tower of the new mill at Sydney, of which the roof was fitting. The south-side of this building was so much injured that it became necessary to take the whole down; which was done, and the foundation laid a second time. [4]

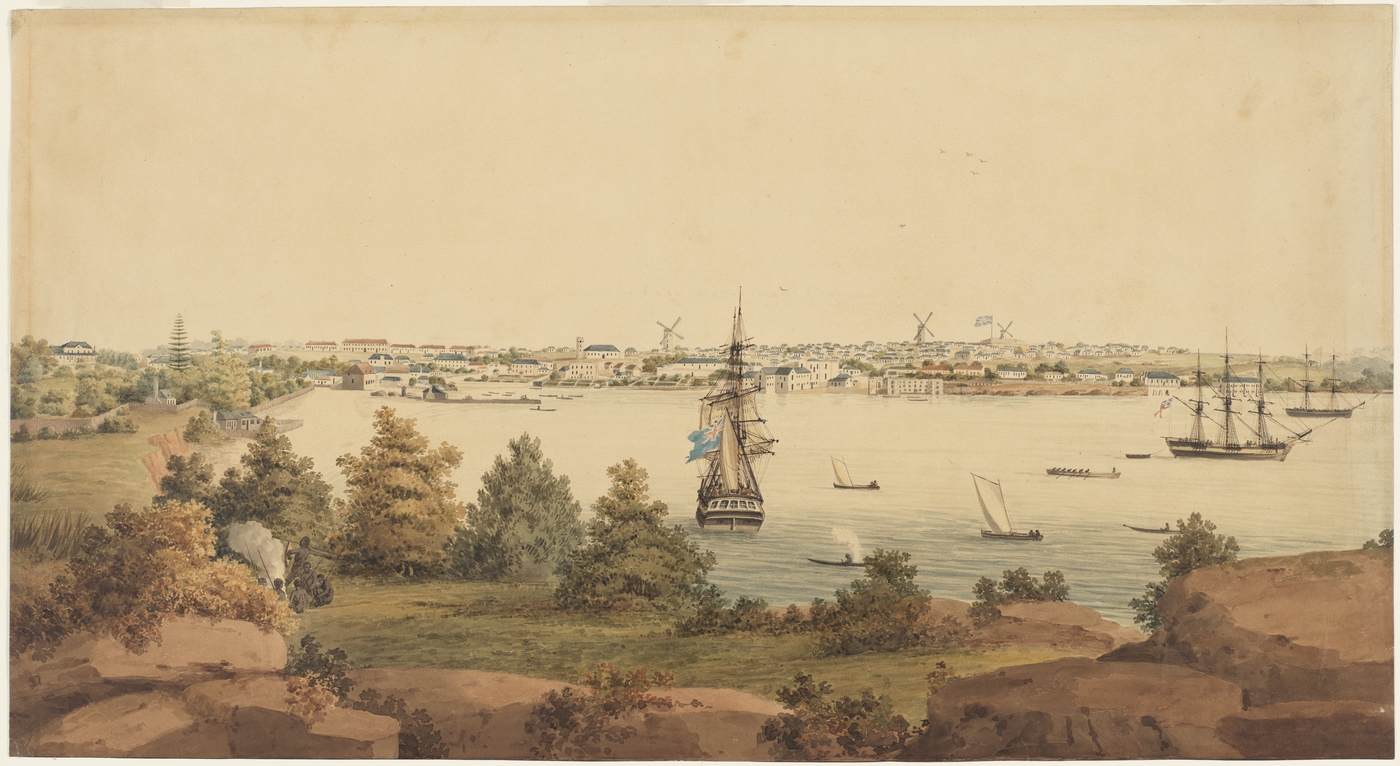

[media]The windmill was slowly repaired between 1800 and 1802 and it continued to function into the 1840s. [5] It was known as the military windmill and it was beautifully captured in Major James Taylor's watercolour 'Sydney Looking South from Flagstaff Hill' of 1821.

[media]A third government windmill was built around 1806 by Nathaniel Lucas near the site where Fort Street public school now stands. This mill was a large wooden structure, known as the wooden government mill. [6]

[media]The building of the first windmills, with their ability to grind much greater quantities of flour, was naturally hailed as an important development by the early settlers – so much so that the windmill's unmistakable form was included in one of the first emblems designed to symbolise the colony. This design featured at the top of the front page of Australia's first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, in 1803. It represented a seated figure marked '1788' with a beehive, plants, picks and shovels, a plough, a ship, a fort, a church, a house and a windmill. Around these were the words 'Thus We Hope To Prosper'. It is clear from this that the ability to cultivate the land and produce enough food was central to the early settlers' hopes for their future and dreams of economic security; in this, windmills would play an important part.

Commercial mills

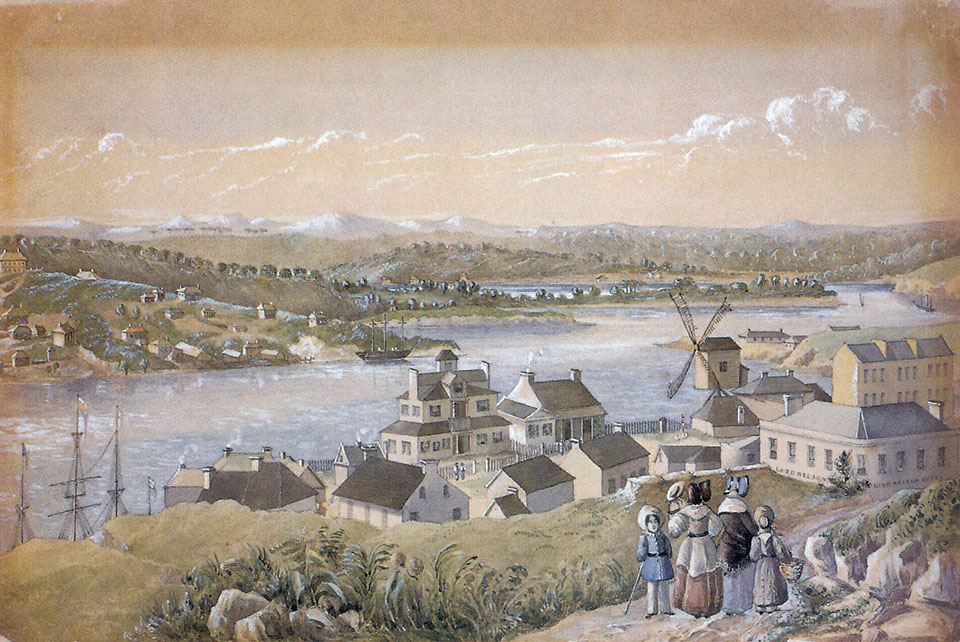

[media]As the colony developed its infrastructure, and shipping, commerce and agriculture became well established, the population grew. The demand for food (flour for bread in particular) soon meant that private windmills overtook the government ones. There was clearly much lucrative commercial gain to be made by men who had the necessary skills and capital to run milling businesses. During the early decades of the nineteenth century, windmills dotted the entire Sydney landscape, all the way from The Rocks to Parramatta. Alexander Harris sailed into Sydney during the 1820s and later recalled

a waterside town scattered wide over upland and lowland, and if it be a breezy day the merry rattling pace of its manifold windmills, here and there, perched on the high points, is no unpleasing sight. [7]

The three eastern mills

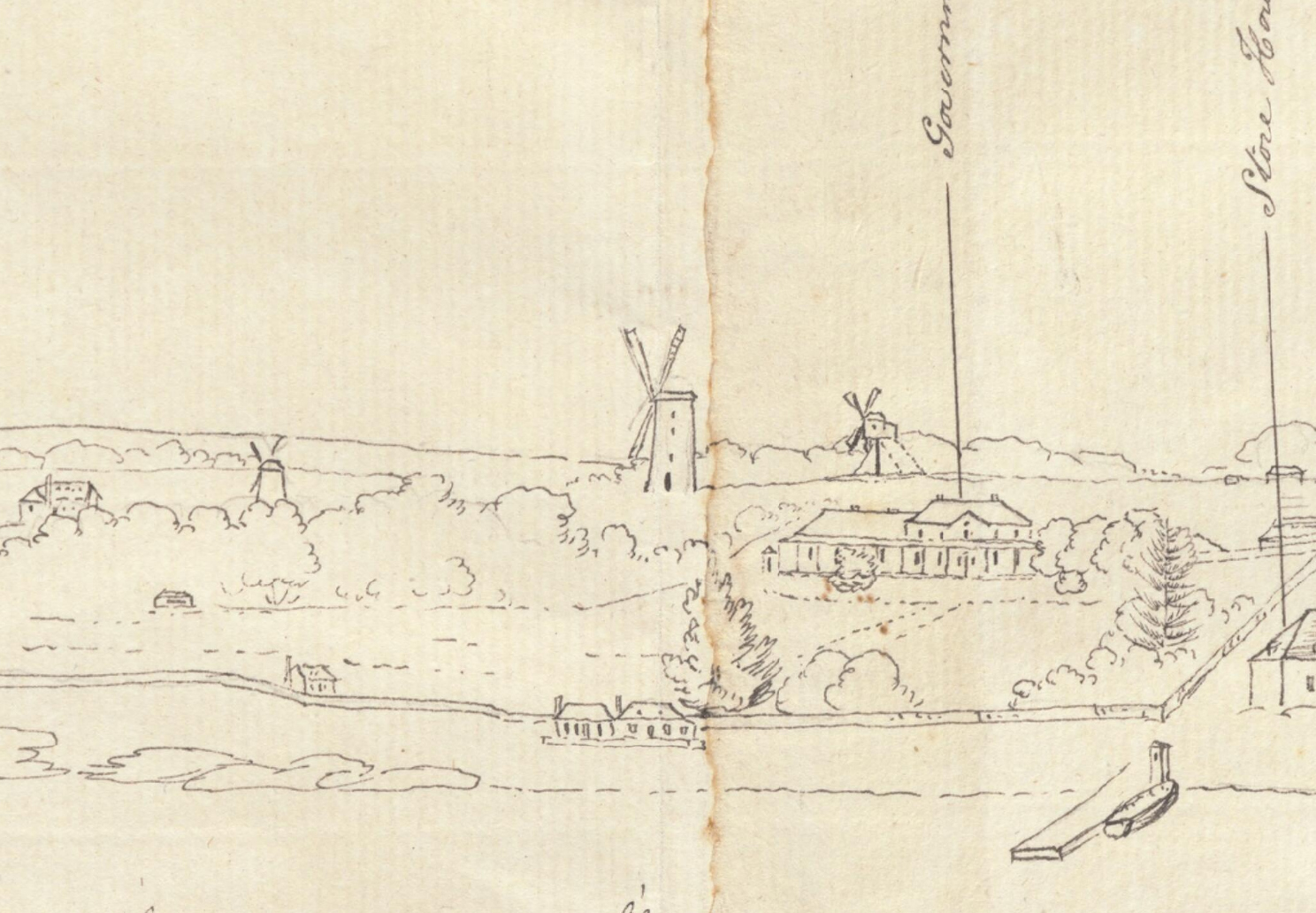

[media]Between the present location of Governor Bourke's statue outside the Mitchell Library and the present site of the Conservatorium of Music 500 metres north, there were, at times, three windmills at work. [8] These three mills on the eastern side of Sydney town were known as Boston's Mill, Palmer's Mill and Kable's Mill. John Boston, John Palmer and Henry Kable all became successful and wealthy colonial entrepreneurs. The convict artist John Eyre painted a delightful watercolour of the east side of Sydney Cove in about 1808 in which the three eastern mills can be seen – Boston's mill on the left partly hidden by trees, Palmer's in the centre on higher ground and Kable's small post mill on the right. In front of Kable's mill is the first Government House, whose site is now marked at the corner of Phillip and Bridge streets. [9] [media]The painting attests to the rapid and prolific development of Sydney within the first 20 years of British colonisation.

Millers Point

Millers Point[media] was originally called Cockle Bay Point. By 1822 there were three wooden windmills erected on the high ground there, west of Sydney Cove, apparently run by a local character, Jack Leighton.[media] Known as 'Jack the Miller', he met an untimely death in 1826 when he fell, 'in a state of intoxication', from a ladder leaning against one of his mills. [10] His original mill was near today's Bettington Street, on the high ground just past Dalgety Terrace. The second mill was built on land granted to Joseph Underwood in 1817 'for the purpose of erecting a windmill thereon'. It was situated west of present day Merriman Street and was demolished in 1842 and replaced by a terrace of three houses. [media]The third windmill, in the Merriman Street area, was still standing in the 1840s on land owned by a Mr Davis. The date of its disappearance is uncertain. [11]

The Pyrmont windmill

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, the landowner and wool pioneer John Macarthur built a windmill on a very high point at Pyrmont. [12] It was built, using local stone, in the triangle formed by Church, Mill and Point streets, later the site of St Bartholomew's church. The mill was still operating in the 1810s and is marked on the 1822 map of Sydney as a lonely structure with no other buildings nearby. However by 1832 it had been deserted and its sails were broken. [13] Because of its elevation it could be seen as far away as the north shore of the harbour, from the high land around the Observatory and even from the South Head Lighthouse. It was depicted in Major James Taylor's 1823 panorama of Sydney and the convict artist Joseph Lycett's many windmill-friendly watercolour paintings of Sydney during the 1820s. [14]

The Darlinghurst mills

[media]Windmills also dotted the landscape on the high ground east of Sydney, linking what is now Kings Cross with Darlinghurst and Paddington. Writing in 1902, Norman Selfe remembered that:

The most picturesque windmills of Sydney, and those whose 'poetry of motion' – 'responsive to the friendly breeze' – first greeted the new arrival by sea, were undoubtedly those which crowned the ridge at Darlinghurst. [15]

The wealthy merchant Thomas Clarkson owned the first of these mills at Darlinghurst, and there were two smaller wooden post mills nearby, very close to where Liverpool Street is now. Little is known of these mills, except that one of them was Kable's mill, which had been moved there from its former site near the Domain. In Kings Cross there were two more stone tower windmills that stood near where Roslyn Street joins Darlinghurst Road. One was owned by Thomas Barker and the other by Francois Girard. Thomas Barker was one of the wealthiest flour millers in Sydney during the 1820s and 1830s and eventually established the first steam mill in the colony at Darling Harbour. Girard was a colourful colonial character, a Frenchman transported as a convict, who soon after receiving his conditional pardon in 1825 became embroiled (together with a few other dubious bakers) in a legal scandal involving the short weighing of Sydney-made bread. This did not deter him however and by May 1826 his advertisements promised

every kind of fancy bread, of a superior quality for gentlemen's tables. N.B. French Hot Rolls at Half past 7 in the morning. [16]

Girard would later become a leading baker and coffee shop owner, ship owner, builder and pastoralist. [17]

[media]Hyndes mill (referred to as the Craigend windmill by the 1860s because of its proximity to the Craigend estate) occupied one of the highest points in the Sydney area, a rocky hill above Kings Cross roughly where Royston Place is now. For a short period, when it was leased in the 1830s to John Hill, it was also known as Hill's Mill. [media] Thomas Hyndes posted an advertisement for a stonemason to erect a tower and complete a windmill in 1825 [18] and the mill opened for business in 1829. It reached a height of 105 feet (32 metres) with sails 140 feet (42.6 metres) long. During the 1850s and 1860s its prominent position and size meant that its sails were a central feature of the Woolloomooloo landscape. [19] Frederick Charles Terry's engraving 'Sydney From the Old Point Piper Road' illustrates the sky and landscape of the area in the 1850s with the sails of Hyndes, Barker's and Girard's windmills high in the sky and visible from many miles away. [20]

Paddington and Waverley mills

Gordon's mill[media] was built in Stewart Place in Paddington about 1829. It was a large wooden post mill sitting on a circular stone base, sometimes referred to as a 'stone and post mill', and bigger than the earlier post mills. This mill is said to have been the second last of the Sydney windmills in operation, continuing until the 1870s. In the 1850s and 1860s, theatre scene painter George Roberts painted many pictures of the eastern suburbs of Sydney, and Gordon's mill features in several watercolours that are now in the Mitchell Library. [21] The storekeeper and amateur sketcher John William Hardwick also produced a watercolour showing Gordon's mill in 1853 [22]. Both paintings are testimony to the ongoing importance of the windmill in colonial daily life and also in the landscapes and skyscapes of colonial artists' imaginations.

Henry Hough[media] owned Hough's mill, which stood on the site now occupied by St Barnabas's church in Mill Hill Road, Waverley. It was a wooden post mill and operated from 1846 until 'it was levelled to the ground on October 1 1878'. [23] It was probably the last Sydney mill in existence. As with other Sydney windmills, it was captured in ink and paint by a number of artists; another watercolour by John William Hardwick shows Hough's mill in 1853 [24] and Samuel Elyard made several paintings of the windmill in the 1860s and 1870s.

Mills in writing

Colonial artists beautifully captured the windmills of Sydney in their landscape drawings and paintings. Yet other contemporaries also seemed to be enraptured by these functional and yet whimsical, pre-industrial romantic structures. In 1823, while a student at Cambridge University, William Charles Wentworth wrote a poem 'Australasia' in which he described the beauties of Sydney – the harbour, the ships, street, square and mansion, church and font and market throng – and at the climax of his description:

The lofty windmills, that with outspread sail

Thick line the hills, and court the rising gale. [25]

Windmills in Sydney would remain close to the hearts of Sydneysiders into the middle of the nineteenth century. In 1851 the Sydney Morning Herald wrote a special report on Woolloomooloo and noted that it was

perhaps, the most delightful little spot within the city boundary… A large number of the 'well to do' persons who earn their living in the learned professions, as well as in trade, have chosen this spot to enjoy the rus in urbe. The crest of the hill is studded with fine dwellings, we might call them mansions, in which almost everything that art and luxury can produce contribute to the comfort and happiness of those who are fortunate enough to reside in them. Intermixed with these houses are several windmills, materially adding to the diversity of the scenery … This is certainly a very pleasing picture to contemplate; pity it is that the prison of Darlinghurst looks frowningly on the whole scene, and reminds us that we are not yet in the promised land. [26]

Remaining traces of mills

[media]Other windmills were constructed at various times at Parramatta, Camden, Campbelltown, Liverpool and Windsor as well as further out at Picton, Mittagong and Bathurst. Yet with the march of industrial progress that characterised the mid to late nineteenth century, steam and coal power increasingly began to take over and the picturesque sails of Sydney's windmills gradually disappeared from the skyline.

[media]Today names like Millers Point, Windmill Street, Mill Hill Road and Mill Street refer to an almost forgotten and lost Sydney landscape. The last remnants of the Sydney windmills have mostly disappeared – although you can still find a few stones of one windmill under the stage at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, discovered during archaeological excavations in the 1990s. Stone from Hyndes mill, the largest mill in Darlinghurst, was later reused to build Beare's Stairs in Caldwell Street. The stone from Thomas Barker's windmill was used to build two terrace houses in Kellet Street, Kings Cross which remain today on the corner of Kellet Lane. Most importantly, however, the windmills' existence will remain forever encapsulated in the watercolours, sketches and paintings of the nineteenth century artists who drew them and left to us a lasting record of their significance to the history of Sydney.

Further reading

The Views of Frederick Charles Terry c. 1862, Fine Arts Press, NSW, 1978

Bertie, CH. Old Sydney. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1911

Cobley, John. Sydney Cove 1795–1800, The Second Governor. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1986

Collins, David. An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 2. Edited by Brian Fletcher, Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975, first published 1802

Fitzgerald, Shirley & Christopher Keating. Millers Point, The Urban Village. Sydney: Halstead Press, 2009

Flannery, Tim (ed). The Birth of Sydney. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 1999

Fox, Len. Old Sydney Windmills. Marrickville: Southwood Press, 1978

Hainsworth, DR. The Sydney Traders, Simeon Lord and his Contemporaries 1788–1821. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1981

Harris, Alexander. Settlers and Convicts; or Recollections of Sixteen Years Hard Labour in the Australian Backwoods. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1954 first published London, 1847

Karskens, Grace. The Rocks; Life in Early Sydney. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1997

Maiden, JH. 'History of Sydney Botanic Gardens'. Royal Australian Historical Society Journal & Proceedings 17, part 2 (1931): 126–44

McPhee, John (ed). Joseph Lycett, Convict Artist. Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, 2006

MacDonnell, Freda. Before Kings Cross. Melbourne: Nelson, 1967

Selfe, Norman. 'Some Notes on the Sydney Windmills'. Royal Australian Historical Society Journal & Proceedings 1, part 6 (1902–3): 96–107

Prout, J Skinner and John Rae. Sydney Illustrated 1842–3. Sydney: Tyrells Pty Ltd, 1949

Tatrai, Olga. Wind and Watermills in Old Parramatta. Marrickville, NSW: Southwood Press, 1994

Waldersee, J. 'Emancipist in a Hurry; Francois Girard'. Royal Australian Historical Society Journal 54, part 3 (September 1968): 238–55

Wheeler, JSN. 'Old Miller's Point, Sydney'. Royal Australian Historical Society Journal, 48, part 4 (August 1962): 301–20

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 2, edited by Brian Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975, first published 1802), 16

[2] Tim Flannery, ed, The Birth of Sydney (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 1999), 149

[3] For the commencement of the building of the second windmill see David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 2, ed Brian Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975, first published 1802), 37

[4] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 2, ed Brian Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed, 1975, first published 1802), 153–54

[5] There is something of a disparity in the historical records as to the exact date when the second windmill was repaired and began to work again. Governor Hunter reported it had been rebuilt and was completed in a despatch to the Colonial Office in London in September 1800. Yet in 1804 Phillip Gidley King who had arrived in the colony in 1800 to take over the Governorship claimed that on his arrival 'only one windmill was finished and at work…The tower of the second was carried only 15 ft. high…this windmill was not finished completely 'till the latter end of the year 1802'. See Hunter to J King, Enclosure no 2, 25 September 1800, in Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 2, 1797–1800 (Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914–25), 561; Governor King to Lord Hobart, Despatch, 1 March 1804, in Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, Volume 4, 1803–1804, (Sydney: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914–25), 467–68

[6] Len Fox, Old Sydney Windmills (Marrickville, NSW: Southwood Press Pty, 1978), 23–24

[7] Alexander Harris, Settlers and Convicts; or Recollections of Sixteen Years Hard Labour in the Australian Backwoods, (Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press, 1953, first published London, 1847), 1

[8] JH Maiden, 'History of Sydney Botanic Gardens', Royal Australian Historical Society Journal & Proceedings 17, part 2 (1931): 136

[9] John Eyre, ‘East view of Sydney in New South Wales’, ca 1809, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (a1528247 / DL Pg 49) http://acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=825865

[10] The coroner concluded it was an accidental death. See Sydney Gazette, 24 June 1826, 3

[11] Shirley Fitzgerald and Chris Keating, Millers Point, The Urban Village (Sydney: Halstead Press, 2009): 16; see also J Skinner Prout and John Rae, Sydney Illustrated 1842–3 (Sydney: Tyrells Pty Ltd, 1949): 30; CH Bertie Old Sydney (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1911): 1

[12] Margaret Steven, 'Macarthur, John (1767–1834)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macarthur-john-2390/text3153, published in hardcopy 1967, viewed 2 May 2014

[13] Len Fox, Old Sydney Windmills (Marrickville, NSW: Southwood Press Pty, 1978), 33–35

[14] John McPhee (ed), Joseph Lycett, Convict Artist (Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2006)

[15] Norman Selfe, 'Some Notes on the Sydney Windmills', Royal Australian Historical Society Journal & Proceedings 1, part 6 (1902–3): 103

[16] Sydney Gazette, 13 May 1826

[17] See J Waldersee, 'Emancipist in a Hurry; Francois Girard', Royal Australian Historical Society Journal 54, part 3 (September 1968): 238–55

[18] The windmill appears in the Ellerslie Panorama which is dated about 1835. See Len Fox, Old Sydney Windmills (Marrickville, NSW: Southwood Press Pty, 1978), 55

[19] For this windmill's prominence see the engraving reproduced in the Illustrated Sydney News, 15 October 1864, p8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page5408351, viewed 19 Jun 2016

[20] Frederick Charles Terry was a noted Australian colonial painter, water-colourist, engraver and designer. In 1855 forty engravings from his sketches were published in The Australian Keepsake. This was in turn republished as New South Wales Illustrated, The Views of Frederick Charles Terry c. 1862 (NSW: Fine Arts Press, 1978)

[21] Works by George Roberts in the State Library of New South Wales’ pictures collection: http://acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/s/search.html?collection=slnsw&meta_e=401498

[22] Hardwick, John W ‘Windmill : Panorama of Paddington 1853, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (PXA 6925, 11) http://acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=446719

[23] Norman Selfe, 'Some Notes on the Sydney Windmills', Royal Australian Historical Society Journal & Proceedings 1, part 6 (1902–3): 105. However there seems to be some uncertainty that this was indeed the correct date and estimates range from between 1873 and 1881.

[24] Hardwick, John W ‘Windmill : Waverley - near Sydney’ 1853, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (PXA 6925, 7) http://acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=446719

[25] William Charles Wentworth, 'Australasia', 1823, available online http://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/wentworth-william-charles/australasia-0009001, viewed 18 June 2015

[26] 'The Sanitary State of Sydney', Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1851, 2

.