The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bodgies and African American Influences in Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Bodgies and African American Influences in Sydney

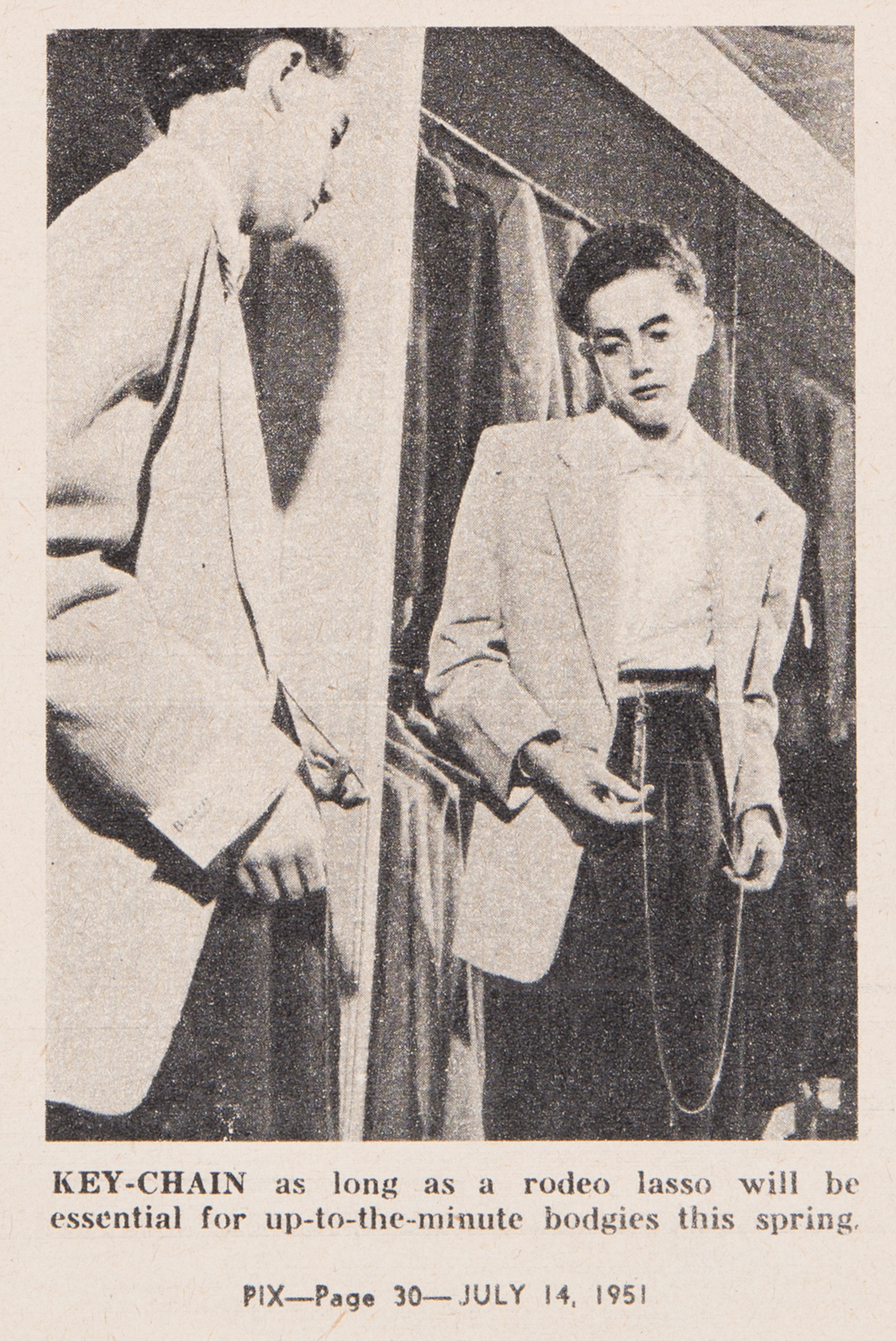

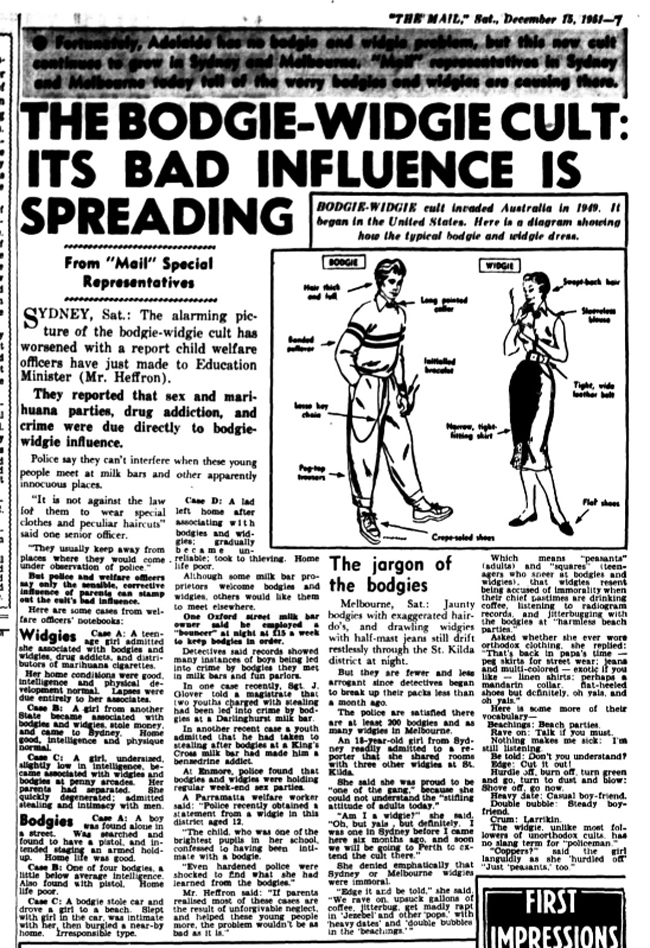

[media]During wartime in the 1940s something approaching a sensual revolution occurred among a small cohort of young men in the inner-city working class suburbs of Sydney. They began to sport big, loose-fitting jackets with brightly coloured shirts, and wore their pants tight at the ankles, while key-chains dangled from their belts. They wore suede shoes, often with crepe soles. Their hairstyles resembled those of American film stars, long at the back and sides with curls cultured over their foreheads. They called themselves bodgies (their girlfriends were widgies) and were directly influenced by African American servicemen who were amongst the thousands of US soldiers clustered in the clubs and streets of Kings Cross, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst. The bodgie style, and the music and fashions that went with it, smoothed the path for subsequent waves of African American cultural influence in Australia, such as rock music, blues, gospel and hip-hop. [1]

Bodgies and black GIs

The bodgie movement, which embraced sensuality and bodily expression, was a rejection of the dry, blokey, anti-emotional male culture of inherited British tradition. [media]Black American culture had begun to enter Sydney, in a very small way, in the 1920s when dances such as the Black Bottom and the Charleston became fashionable, brought to Sydney by films such as Stormy Weather and Stairway to Heaven. The wider adoption of black American culture began in 1943, when US soldiers, including thousands of black GIs, were stationed in Sydney. [2] [media]With the black GIs came V-discs, which were rhythm and blues records issued to black service personnel by the US Army. African American musicians also visited Sydney. The soldiers and musicians were the vanguard of a gentle invasion of African American culture.

Oral history about bodgie culture

This article is drawn from interviews conducted with men and women, now elderly and some since deceased, who were bodgies and widgies in Sydney during the 1940s and 1950s. [3] These respondents reported that the presence of large numbers of black American troops, in civilian clothing, had a profound influence upon their cultural choices – more so than films they viewed or the GI V-discs which introduced them to rhythm and blues, spirituals, jazz and swing. The fashion, music, dance, speech and body language of the young black Americans who were in Sydney during that period were utterly dissimilar to the pre-war larrikin cult or the English fashions of the middle and upper classes. While changes in Australian street culture were gradual and irregular, and not all of the influences outlined in this chapter were adopted by all Sydney bodgies, many took on the whole 'black thing', as one respondent termed it, as soon as they were exposed to it. Widgies, who had no female black models in Sydney to follow, took their fashion cues from 1940s and 1950s films, but embraced other elements of this new youth culture.

The nature of African American influence

The former bodgies and widgies interviewed during research for this article have said that many older Australians regarded African Americans as uncivilized and perceived jive dancing as primitive sexuality. The bodgie cohort rebelled against their elders by engaging with the 'primitive', that is, the physical. This was not a process of 'Americanisation', as that term is widely used and generally understood. Bodgies, who were disempowered young Australians, adopted elements of American culture that were practiced by disempowered African Americans. Bodgies did not just adopt African American fashion, but absorbed it into their own bodies and bearing. This is a process I refer to as 'performative embodiment', in which the bodgies consciously appropriated the sensual and physical characteristics of African Americans, and identified themselves with 'the primitive'. [4]

American influences on bodgie fashions

Bodgie style was influenced by suits worn by young African Americans in the first half of the twentieth century, which were in turn influenced by gunnysack clothing worn on cotton plantations. The gunnysack shapes found their way to Harlem and Chicago and by the 1940s had become modified and stylised into a suit, which was identifiably black and a sort of badge of black solidarity. These suits exaggerated male characteristics by padding the shoulders, and the looseness of the clothing allowed men much more movement, stylish and exaggerated, than was strictly necessary to propel the body forward from one step to the next. This walk was a performance, designed to be looked at. [5] More colourful variations of the so-called 'zoot suit' may be seen on Sammy Davis Junior and in the all-black musical, Stormy Weather.

Bodgie clothing more or less copied these suits. The trouser knees were 13–14 inches (32.5 to 35 cm) in diameter, tapering down to an eight to eight-and-a-half inch (20 to 21 cm) cuff. Jackets were loose, 'box-backed' and quite a bit longer than the standard Australian or British garments. Many bodgies sourced their garments directly from GIs, and visited American ships at Woolloomooloo docks, both during and after World War II, to buy clothing from black American sailors. [6]

The trade in black fashions

Martin Vaughan was one fan who frequented the docks to meet American sailors, during and after the war, and who preferred buying the disks that were being offered by black seamen because the music was more exciting and better for dancing than dance records then available in Sydney. He and his friends felt American culture meant black American culture, and they wanted to make this culture theirs, and were in contact with black American seamen who 'were frequent visitors to the Gaiety Ballroom in the Fifties.'

Val Squires was a teenager in Sydney during the 1940s and early 1950s and frequented dance halls, milk bars and private parties where black Americans were present and where V-discs were played. A self-professed follower of fashion, Val said young Sydney men purchased clothing, in particular drape jackets, from African American soldiers on leave, and from African American sailors on commercial vessels in port at Woolloomooloo. Other respondents had drapes made by Sydney tailors, in particular Andy Ellis in lower Pitt Street. Ellis told me in interview that he made hundreds of 'zoot suits' and drapes for Sydney's bodgies during the late 1940s and into the 1950s. [7]

Johnny Griffin remembered going to the docks to buy clothing which he described as 'sexual'. Kenny Lee, a Sydney bodgie who started the bodgie cult in Perth during the early 1950s, made a similar comment. Warren Poltmeir, another of the bodgies in this cohort, visited the ships and bought records and clothing from American seamen, black and white – 'I wanted to be the sharpest, and to do that I bought clothes from the black Septics'. 'Septic tanks', of course, was Australian rhyming slang for 'Yanks'. [8]

David Perry, who later became an independent film-maker, said that before he met African Americans and began wearing bodgie clothing he had been looking for, but not finding, a sense of 'who he was'. He remembered going to the ships docked at Woolloomooloo during the late 1940s and early 1950s to buy records and clothing, mostly from black American seamen, who brought extra items when they travelled to Australian ports, in anticipation of the demand for their style of clothing.

Joe Lane remembered the carefree attitudes of the black Americans visiting Australia, both during and after the war. He stated that he set out to make his own body language, clothing, walking, slang speech and other expressions of fashion as much like African Americans as possible, 'training' his body, as he put it, to be like theirs. Their clothing impressed him deeply.

The clothes we had been wearing were tight and skimpy, English-style. There was something attractive to us about the idea that you could waste clothing (his emphasis). It was like a statement, a kind of slap in the face to the powers that be.

Body language and 'cool'

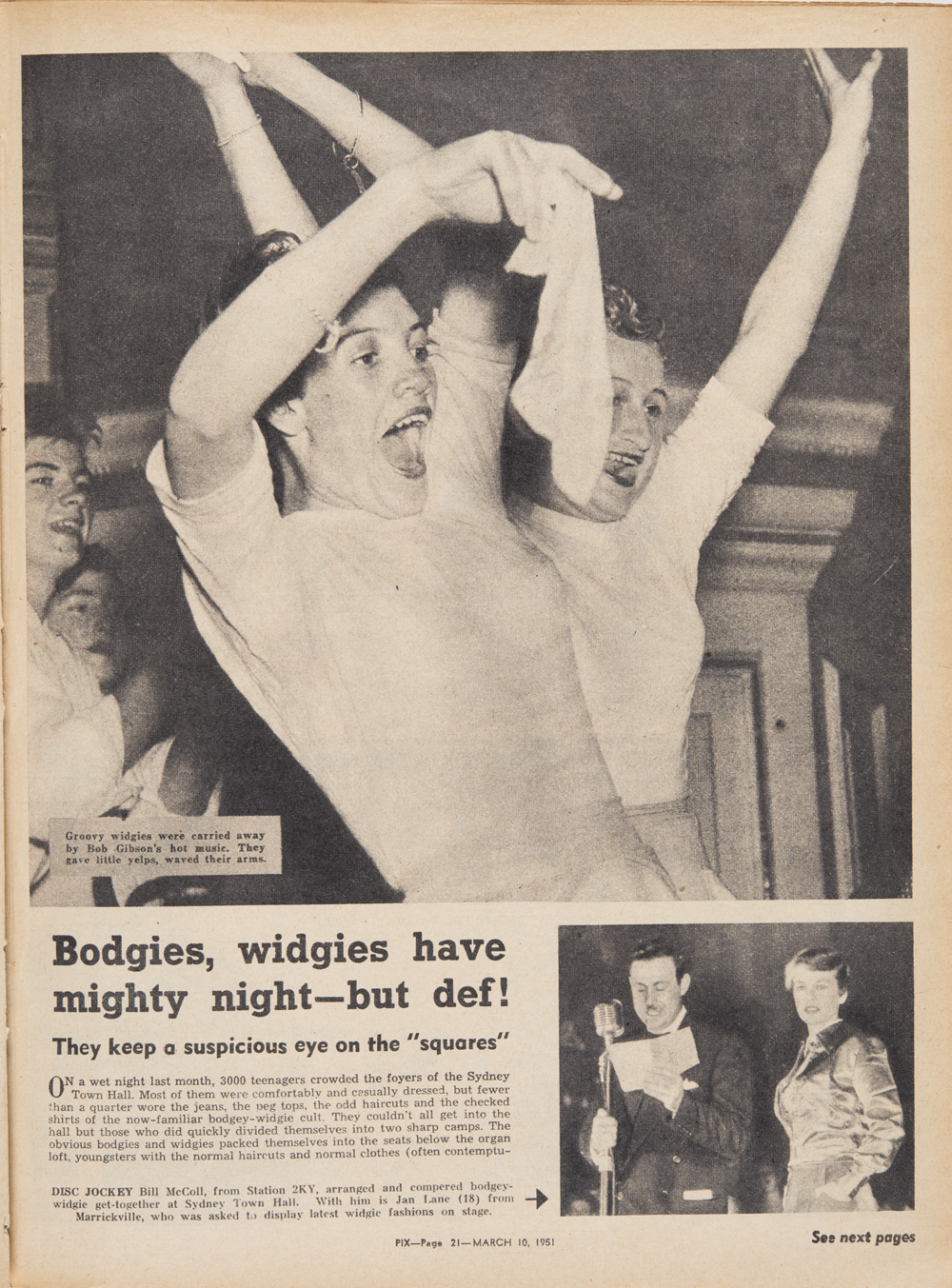

Respondents noted that the African American soldiers always looked as though they were giving a performance. They had a rolling gait, expressive hand gestures, and a 'cool' mien. The African American soldiers also brought with them their loose, highly rhythmic, circle-based dancing, that emphasized fluidity in the hips, free arms, tapping feet and a joyful, insouciant attitude. [9] When young Australians from working-class areas met and fraternised with the African Americans they were impressed, and immediately took on this new way of moving to music. It was so different, so much sexier and so much more joyful than, say, the Pride of Erin or the foxtrot. [10]

Some respondents attempted to express the extent to which they learnt what might be termed a mode of being from the black Americans they met. Jean Jurd said 'I learnt from the (Negroes) that it was OK to move one's body sensuously', a comment echoed by others including Peter Collingwood and Johnny Griffith. The freedom of the body enjoyed by African Americans, whether on the dance floor or in simple ambulation, was, according to a number of respondents, immensely attractive to many young Sydney people during this period.

Respondents noted that group dancing became more common during this period, attributing the change to the adoption of African American culture. Groups of bodgies and their consorts would often, at the Gaiety and especially at the larger Trocadero Ballroom, gather together in the centre of the dance floor and dance as a group, rather than in pairs. This type of dancing enabled individuals to move as they pleased without having to match the movements of a partner. This in turn enabled the development of more individual displays of technique, body sensuality or style, uninhibited by the presence of a partner, as might be the case with the dominant dance style of jive.

Contemporary magazine articles on the subject of youth culture reveal the rise of group dancing. In June 1947 PIX magazine showed Australian girls jitterbugging on an American aircraft carrier in Sydney Harbour with American sailors, under the heading 'Navy Hepcats'. [11] The following month PIX featured Burt's Milk Bar in Darlinghurst Road, Kings Cross, with bodgies and their consorts standing in groups, or jiving. [12] This is most clearly the case in the cover photograph of the story in PIX on 3 December 1949, showing respondent Martin Vaughan as a young bodgie, jiving with a partner at the Gaiety Dancehall in Oxford Street, Darlinghurst, clearly wearing clothing influenced by African American styles. [13]

The sensualisation of slang

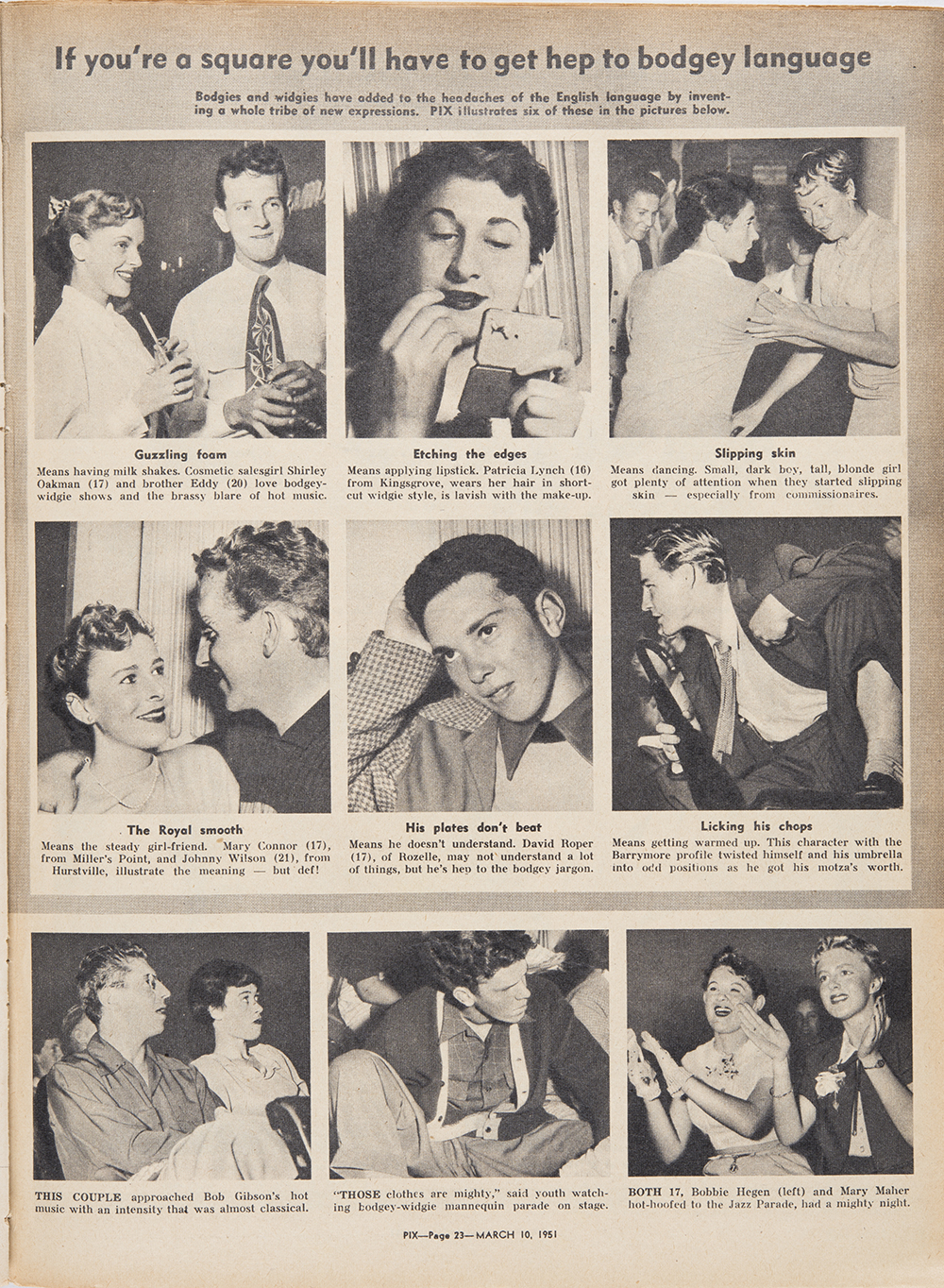

[media]The speech patterns of African Americans were copied by the bodgies, as minutely as possible. Respondents said they would listen very intently to the speech of black Americans they met, deliberately engaging them in conversation to hear how they talked and, according to respondents like Gordon Mutch, their slang. Bodgies reproduced these speech patterns as part of a process of absorbing an African American character into their bodies and minds – as Mutch and Lee put it, this was part of trying to be 'as black as possible'. [14]

A number of respondents have indicated that African American slang was considered sensual. Terms like 'hip', 'dig', 'cool' and 'sharp', some of which can be traced back to West African words, came into the everyday slang of bodgies during this period, according to Mutch, Ian Jewkes, Vaughan, Marshall, Collingwood and several others. They thought the use of such terms and emphases would make them more attractive to women, and more up-to-the-minute, more of a leader. However, not all bodgie slang was of African American origin, indicating that a process of bricolage, the merging of several cultures, was ongoing among bodgies during this period. A number of words inherited from British culture, such as 'peasant' to indicate a person who had not adopted bodgie styles, or 'scarper', meaning to leave, were retained alongside African American terms.

Language also served to shield bodgie culture from parents and other authority figures. Gordon Mutch was one of several bodgies who said the use of African American slang was a private 'creole', a teenage language that adults would not understand. According to these respondents bodgies spoke sensually, with a rising and falling inflection adopted from African Americans, that contrasted with the flat, monotonous accents of the older Australian working-class generation.

The 'sharpest cat in the Cross'

Respondents Martin Vaughan [media]and Kevin Caporn believe there were several hundred bodgies in inner-Sydney during the mid to late 1940s, if not 2000. Although most of them, by their own definitions, were of working-class or lower-working-class backgrounds, they appear to have regarded themselves as breaking away from the stereotypes of class which had come from the old world. While bodgies noticed each other, they did not seek publicity, or to be noticed by the majority population. Sydney author John Clare, in his book Bodgie Dada and the Cult of Cool, wrote

Black American writer Ralph Ellison equated coolness with invisibility. The main protagonist in his 1992 novel Invisible Man reached the conclusion that the individual Negro was invisible to most white people, and that this invisibility, if coldly accepted, could engender a heady internal freedom, which could lead in turn to being hip, and cool, or detached, in an almost Buddhist sense. [15]

The man known as the 'sharpest cat in the Cross' embodied this coolness in Sydney. It is significant that the respondents who mention him, including Joe Lane, Martin Vaughan and Johnny Griffin, could not agree on his name, which was variously given to me as Kenny Lee, Donny Mannion, or several Greek and Italian names. Perhaps he concealed his name to avoid the police, or perhaps a number of bodgies, at different times during the late 1940s and early 1950s, answered his description. Whoever he was, he was extremely good looking, successful with women, had impeccable taste in African American-styled clothing, was hip, sharp, knowledgeable about music, cool and tough. He may have been a mythic figure, created by word of mouth to represent an idealised version of 'bodgiedom' which no individual could meet – a projection of all that bodgies aspired to become. That several respondents claimed to have known him does not prove that they were all meeting the same person. The 'Kings Cross Yank' may also have been a mythic figure, used to represent a young Australian who embodied American modes of behaviour.

Fraternising with African Americans

The US Army was segregated during World War II and US military authorities generally frowned upon fraternization between African American soldiers and Australians, upholding racial divides within their own forces. Despite this, the Red Cross selected a number of young Aboriginal women from Christian missions near Sydney to dance with the black Americans during World War II. While it has not proven possible to interview any of these women, two of them, Christine Hinton and Daisy Hickey, gave an interview for ABC Radio during the 1980s in which they stated that they were deeply influenced by the confidence and racial pride the young African American men displayed. This was both a cultural and a political influence on dispossessed Australians.

Young white bodgies refused to obey restrictions on fraternisation. Many of the respondents, including Luke Cori, Vaughan, Mutch, Perry, Lane and others, stated they went out of their way to place themselves in the company of black Americans. They described the amount of time and energy they expended trying to make the moves and appearances of the African Americans 'their own', which involved not only appearance but also performance. 'Fraternising with the Negroes was what we did on weekends' said Marie Ermington. [16]

Sites of fraternisation

Bodgies met African Americans at particular venues in Sydney. The Gaiety Dancehall, which was only the size of an average suburban church hall, was located behind a milk bar and fruit shop in Oxford Street, Darlinghurst. To enter it, patrons had to pass through the milk bar off the street. At one end, on a stage, a swing band would play on Friday and Saturday nights. Chairs lined the walls and women would sit in a line on one side of the hall, men on the other side, or, more often, standing around in groups. When the band started up men would walk across the hall and ask women to dance, and in no time the floor would be packed. According to respondents, jiving was the overwhelming favourite form of dance, though during slow numbers a dance called the 'Creep' – basically a shuffle with male and female bodies pressed together, hands held at the side – would start. In the 1950s a mirror ball shone coloured lights over everything, creating a slightly surreal atmosphere. Jiving was a milder variation of jitterbugging, with much less flinging around of the female body by the male. Skirts still flew up, especially in the 1950s when hooped skirts became fashionable, enabling males to glimpse female legs and panties. The site of the Gaiety Dancehall is now occupied by a supermarket. [17]

One night a week bodgies converged upon the 'Troc', The Trocadero Ballroom in George Street, near the intersection with Liverpool Street. This was a large custom-built ball-room which featured a swing band from the 1940s onward, and where 'modern' dancing – mostly jive or creep – would take place.

An important venue for black servicemen between 1943 and 1945 was the Booker T Washington Club. It was located near the top of Albion Street, Surry Hills, in a Georgian building which still stands and was a registered club under the control of the American Red Cross. Swing bands played most nights, African American musicians sat in and patrons jived to the music, although the creep was discouraged. As was the case in the other clubs, the proprietors viewed bodgie patrons with suspicion and mistrust, owing to their media-driven reputation for violence.

Pete Sawyer's barber shop, in what is now the Watters Gallery building in Darlinghurst, was a site of fraternisation between white youths, many of them bodgies, and black Americans. The tradition of barbershop fraternisation was still strong in the United States during this period, and it may well be that African Americans felt comfortable gathering in a barbershop, especially one so close to the Booker T Washington Club. V-discs were played there, clothing was admired and discussed, and black American slang was modelled. [18]

Kings Cross, which became famous in this period for night-time entertainment, was rarely visited by African American servicemen – respondents report that US Army military police generally picked up any African American servicemen seen north of Oxford Street. While it seems that some black Americans took the risk of crossing Oxford Street to frequent brothels, the only site in the Cross where fraternization occurred was Burt's Milk Bar, on Darlinghurst Road. Although dancing there was limited to spontaneous movement around the jukebox, respondents remember that young people went to Burt's to find out where the parties were, meet new people, and make advances to members of the opposite sex, displaying jive-talk, clothing or 'gear'. The site is now a McDonalds.

Late night jazz

Black GIs, many of whom had been professional musicians before they were conscripted, turned up nightly to the Booker, joining with white Sydney musicians. Many respondents, former musicians at the club, noted how much they learnt, on an informal basis, at the club during the nightly dance sessions.

Musical influences did not end with the war and the closing of the Booker. During the 1950s many Sydney jazz musicians played with black American musicians at nightclubs and jazz clubs around the city. Among the black musicians who participated in these informal jam and skill-sharing sessions through the 1940s and 1950s were drummers JC Heard, Jonah Jones and Jessie Martin, piano players Nat Cole and Teddy Wilson, trumpeters Rex Stewart and Dizzy Gillespie, tenor saxophone player Coleman Hawkins, and singer Al Hibbler.

The most fertile exchanges took place during late-night jam sessions held every night in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when musicians from all over Sydney would gather at a particular night spot after the patrons had left to play together, swap yarns, joke and smoke marijuana. Sydney musicians who participated in these sessions include Alan Geddes, Norman Erskine, Ed Gaston, Ron Falson, Len Barnard, George Golla and Jim Blevins. [19]

Spectacle and rebellion in street culture

African Americans in Sydney in the 1940s and 1950s consciously created a spectacle on the street, adopting extravagant body movements, apparently intended to convey a larger-than-life appearance. Respondent Adrian Rawlins, a gay Melbourne poet who frequently visited Sydney during this period, stated that he had always found black Americans attractive because of their visual appeal. To be as 'Negro' as possible was to become more attractive socially and sexually. Collingwood stated 'the sharpest guys pulled the chicks, not necessarily the best-looking guys'.

Bodgies were quick to take on these elements, and embellished them with their choice of colours and clothing styles. Melody Maker reported in June 1941

…tough-looking lads in fearful pink suits…strange, thick-soled rubber shoes, leaping and gyrating like Dervishes to the rhythm of…a swing band. [20]

Bodgies competed to appear flamboyant and sensual, in opposition the conformity of mainstream Australian youth cultures. The colour pink, associated in the public mind with softness and sensuality, was favored by bodgies for shirts, jackets, pants, socks and even shoes. Although bodgies did fight – often, respondents claimed, in response to attacks on their appearance – the evidence of respondents is that that sex, love, and sensual excitement generally were at the core of the bodgies' agenda.

[media]The respondents interviewed for this article remember their years as bodgies as a time to seek new ideas and embrace fun, sensuality and spectacle. It was a rebellion against the dull years of the Depression and the War, the conformism of the dominant Anglo-Irish culture, and their parents' generation. Bodgies – part of the first generation recognised as teenagers – saw African American cultures as a way to be different.

References and further reading

This article is informed by nearly 100 interviews that were collated over many years from the 1990s until 2009. They included musicians, bodgies and patrons of the Booker T Washington Club. Some were members of the Jazz Action Society.

John Clare. Bodgie Dada and the Cult of Cool. Sydney: University of NSW Press, 1995.

AE Manning. The Bodgie: A Study in Psychological Abnormality. Wellington: AH Reed, 1958.

ED Potts and A Potts. Yanks Down Under. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Jon Stratton. The Young Ones. Perth: Black Swan, 1992.

Richard Waterhouse. Private Pleasures, Public Leisure. Melbourne: Longmans, 1995.

Richard White. 'Americanization of Popular Culture in Australia'. Teaching History, August 1978.

Shane White and Graham J White. Stylin': African American Expressive Culture from Its Beginnings to the Zoot Suit. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Notes

[1] Jon Stratton, The Young Ones (Perth: Black Swan, 1992); Jon Stratton, 'Bodgies and Widgies in the 1950s', Journal of Australian Studies, November, 1984; AE Manning, The bodgie: a study in psychological abnormality (Wellington: AH Reed, 1958); Keith Moore, 'Bodgies, Widgies and Moral Panic in Australia 1955–59', paper presented at Social Change in the 20th Century Conference at University of Queensland, October 2004

[2] Ralph Barry, They Came This Way (Roseville: Kangaroo Press, 2000); Interviews with David Perry, Paula Langlands, Martin Vaughan, Joe Lane

[3] The Respondents for this article were nearly one hundred people who frequented the Booker T. Washington Club. They included musicians, bodgies, and young people attracted to the joy and music of the Club

[4] Keith Moore, 'Bodgies, Widgies and Moral Panic in Australia 1955–59', paper presented at Social Change in the 20th Century Conference at University of Queensland, October 2004

[5] Shane White and Graham J White, Stylin': African American Expressive Culture from Its Beginnings to the Zoot Suit (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999)

[6] Interviews with Lane Vaughan and Luke Cori

[7] As a teenager Val Squires visited the Club and enjoyed the music and the dancing.

[8] Johnny Griffin visited Sydney from Perth, was a bodgie, and absorbed performative African American culture in clothing, walk, slang and dance. Kenny Lee, David Perry and Warren Poltmeir were Sydney bodgies.

[9] John McDonald, The Bodgie, BA Honours Thesis, University of Sydney, 1951

[10] John Clare, Bodgie Dada and the Cult of Cool (Sydney, University of NSW Press, 1995)

[11] PIX, 28 June 1947

[12] PIX, 19 July 1947

[13] PIX, 3 December 1949

[14] Respondents Gordon Mutch, Tommy Potter, Peter Collingwood and others, all bodgies

[15] John Clare, Bodgie Dada and the Cult of Cool (Sydney, University of NSW Press, 1995)

[16] Respondent Marie Ermington was a widgie who frequented the Booker T Club

[17] ABC TV Documentary Swingers, 1999

[18] Respondent Chuck Hall, a jazz musician who attended Sawyer's barber shop regularly, and Tony Barker, another attendee, gave almost identical testimony about this venue. T Barker, 'Durham Hall', City of Sydney Historical Society Newsletter, 4, no 10, August 2004

[19] All of these men were swing or jazz musicians working in Sydney at that time, who were employed in the resident swing band at the Booker T. Club; Andrew Bisset, Black Roots, White Flowers (Sydney: ABC Enterprise Press, 1979); Bruce Johnson, 'Naturalizing The Exotic', Jazz Planet Magazine, October 2008

[20] Melody Maker, June 1941

.