The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Hyde Park Barracks archaeology

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Archaeology of the Hyde Park Barracks

Artefacts [media]from the Hyde Park Barracks represent one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of nineteenth-century institutional material in the world. Items found in under-floor cavities include large quantities of textiles and clothing fragments, old newspapers, religious documents, clay tobacco pipes, sewing tools and much more. These artefacts are mainly associated with two groups of women: young immigrant females, who passed through the Immigration Depot at the Barracks between 1848 and 1886, and pauper women, who lived on Level 3 of the building when it served as a Destitute Asylum from 1862 to 1886. This collection has recently been the focus of a major investigation by the Archaeology Program at La Trobe University in Melbourne, supported by the Historic Houses Trust of NSW and the Australian Research Council. [1]

There are more than 100,000 archaeological items in the collection. Around one-third were recovered when excavations were carried out in the early 1980s as part of the first 'Big Dig' in Sydney, when the Barracks was converted into a museum. Trenches were dug within the main dormitory complex, at the front and rear of the building, and within the northern range. Artefacts included substantial quantities of building debris, animal bone, and broken glass and ceramics. This material dates from the earliest phase of construction in 1817–19 right through to the 1970s, and relates to a wide range of occupants including convicts, Irish female orphans, immigrant women, and various courts and legal offices.

The Hyde Park Barracks was one of many institutions established in the nineteenth century to protect and support the destitute, orphans, 'lunatics', and other vulnerable groups. Material from the underfloor collection is highly significant for reconstructing the lives of women in the Destitute Asylum, many of whom spent years living in the crowded conditions there. The Asylum was largely self-sufficient, with the stronger women doing all the cooking, cleaning and sewing of clothes and bedding. They were also responsible for the care of elderly women who were too frail and ill to take care of themselves. Over the years, the women swept and stashed large quantities of debris into cavities beneath the floorboards, and it is this material which has been a special focus of archaeological research. The artefacts reveal important details about the work of the inmates, their clothing, religious devotions, leisure activities, and health and sanitation.

Tobacco pipes

More than 4000 fragments of clay tobacco [media]pipes were found at the Barracks, including 1014 from Level 3, emphasising the prominence of smoking among the asylum women. Only 303 pieces came from Level 2 however, suggesting the young immigrant women were far less likely to smoke. The marks of 35 different pipe makers were identified in the collection, including large numbers of well-known Scottish manufacturers such as Thomas Davidson, Thomas White and Duncan McDougall. There were also local Sydney makers including William Cluer, Joseph Elliott, Samuel Elliott and Jonathan Leak, along with Sydney tobacconists such as Hugh Dixson, Edwin Penfold, William Aldis and Myers & Solomon. There were also more than 250 [media]matchboxes, and thousands of matches, in the underfloor collection. The matchbox trays and covers were made from wood, and came mostly from Sweden, Finland and England.

The asylum inmates were each entitled to a fig of tobacco as part of their weekly ration. Smoking for many was a simple indulgence, providing comfort for those beset by old age or infirmity. While immigrant women came from a social class that increasingly frowned on women smoking, the destitute inmates continued to smoke for the simple pleasure it offered.

Many of the clay pipes were almost completely intact, and could not have fallen accidentally between the floorboards. Instead they had been deliberately hidden for later retrieval. With so many inmates and so little privacy, tucking pipes, tobacco and other items beneath the floor was one way of retaining ownership of private possessions. Most of the clay pipes were also heavily blackened, showing signs of intensive [media]use. Others had had most of the stem removed, meaning the women smoked the pipe close to their face to increase the 'hit' of nicotine.

The landing at the top of the stairs was a favourite place for the women to smoke, along with the yard at the rear of the compound. The yard had been enclosed during the 1860s to separate the asylum women from the other functions of the complex. The inmates used the area for laundry work and bathing. Excavation recovered 516 clay pipe fragments, indicating that the women also used the area to escape the close confines of the upstairs dormitories, to enjoy the open air, and gossip and smoke in peace.

Spiritual lives

Numerous religious items were also found beneath the floor of Level 3, providing insight into the spiritual lives of the asylum women. Items include several hundred paper fragments from the Bible, prayer books and religious tracts, along with rosaries and devotional medals. While visiting clergymen distributed large quantities of evangelical 'improving' literature, the inmates expressed their own religious feelings in more personal, private ways. The archaeological evidence also indicates that the Catholic women were segregated from Anglicans, mirroring the wider sectarian division in colonial Australia.

Titles of [media]moralising books and pamphlets included Are You Afraid to Die?, The Prison Death-Bed, Litany for the Sick, and Advice to the Dejected. These must have been confronting subjects for the sick or elderly inmates, although they were probably the target audience for such tracts. Other titles, such as Self Help and Sunday Rest, stressed personal morality and faith as keys to self-improvement, while an intact book of moral instruction, The Economy of Human Life, included chapters on modesty, prudence, temperance and chastity. This [media]book was written by the 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773), best known for his witty and shrewd letters to his illegitimate son: the book describes the moral duties of men and women, of masters and servants, and prescribes proper conduct with reference to a range of human conditions.

Most of these tracts were brought into the asylum from the outside and expressed the views of evangelical reformers and missionaries. There were also artefacts, however, that reveal more private religious feelings, items mostly from the Catholic tradition. These include the remains of at least four rosaries, a scapular, and six devotional medals, including examples to Mary and Saint Bernard. All of these items were found on the south side of Level 3, suggesting that the Catholic women occupied the two south-side dormitories where they could look out on St Mary's Cathedral, while the Protestant women, on the north side, had easy access to St James Anglican church directly across Macquarie Street.

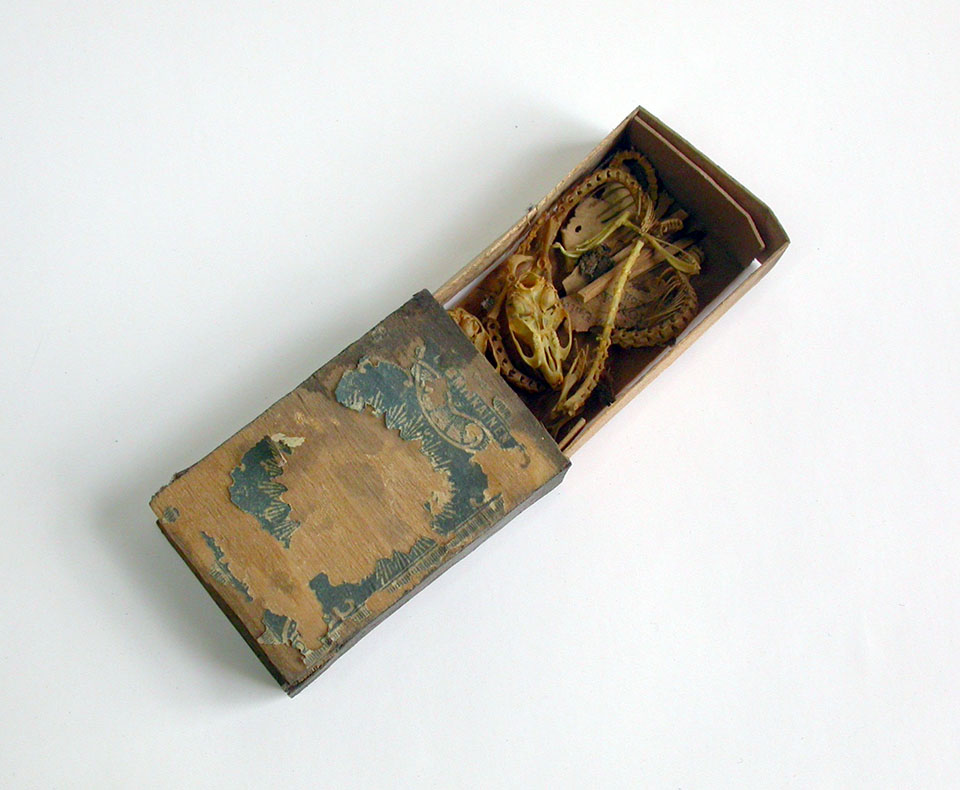

Another item from the underfloor collection may represent an item of ritual folklore. A matchbox containing the [media]skeletons of several mice was recovered from the sub-floor space on Level 3, just inside the doorway to the eastern balcony. This appears to be some kind of superstitious item, relating to the traditional practice of placing an old boot or a dead cat in building cavities as protection against evil influences. [2] The matchbox contains the skulls of two mice, three pelvises and sections of articulated vertebral columns and tails. A small scrap of newspaper below the bones shows no sign of staining, which suggests that the skeletal material was placed carefully and deliberately within the matchbox after the bodies had decomposed and dried out. This artefact appears to belong to a long tradition of concealing objects within buildings to protect against evil spirits. The threshold location of the matchbox may also be significant, on the boundary between inside and outside, intended as a 'spiritual' barrier.

Health and medicine

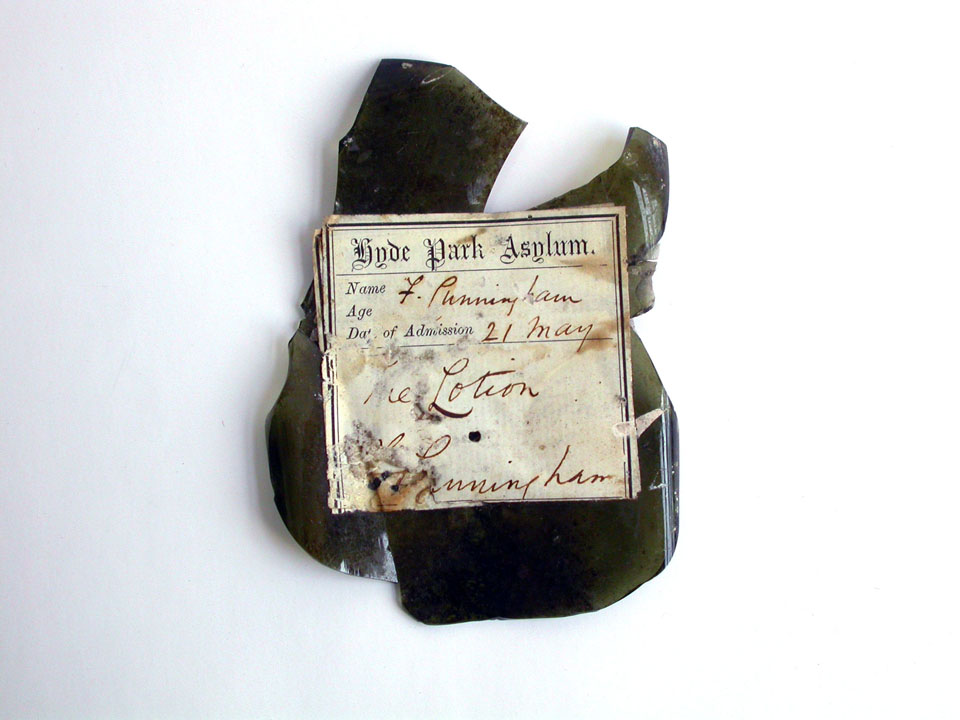

Health and sanitation were also vital where 200–300 asylum inmates lived in cramped dormitories. Pharmaceutical bottles indicate some of the medical conditions of the women, while the reuse of [media]gin and schnapps bottles to store medicines indicates the often makeshift response to providing medical support. Bottles with preserved paper labels were marked 'Raspberry Vinegar' (for sore throats and coughs), 'Tincture of Digitalis' (for regulating the heartbeat), 'Aconit' (for pain relief) and Chloroform (an anaesthetic). Commercial remedies were also found, including Dinneford's Solution of Magnesia (a laxative) and Cockle's Antibilious Pills (for settling the stomach). [3] Several bottles have labels with the names of patients still legible, including Alice Fry and Francis Cunningham. There is also a round wooden disk marked [media]simply 'The Ointment/Mrs Harris' in brown ink.

Inmates were responsible for dispensing medicines in the sick wards, but some of these women were barely literate, and relied on remembering the verbal instructions given to them on the doctor's weekly visits. The medicines were stored on mantelpieces, and some patients simply took their own dosage when required, but the risk of taking a poisonous lotion instead of medicine was very real.

Daily labour

Work was central to the lives of the women, including the sewing and repair of all the clothing and bedding used in the asylum. Even for the old and feeble, simple stitching and darning provided useful work to perform. Archaeological evidence includes thousands of sewing items, such as pins, needles, thimbles and cotton reels, along with textile scraps and leather offcuts.

Sewing pins were small and easy to lose, with more than 4000 pins found in the underfloor spaces. Wooden cotton [media]reels were also common, with more than 80 in the collection. These were often hourglass in shape with a deep waist and a conical flare at each end. Surviving paper labels indicate that the most common thread manufacturer represented in the Barracks material was J Brook & Brothers of Yorkshire, while other makers included I & W Taylor of Leicester, Griffith & Son of London, and Clark & Co of Glasgow. Mass-production of cotton reels began in the 1840s, when cotton replaced linen as the most common sewing thread. The mechanisation of cotton spinning, spool production and thread winding occurred just in time for the appearance of self-acting sewing machines, including Isaac Singer's, in the 1850s. [4]

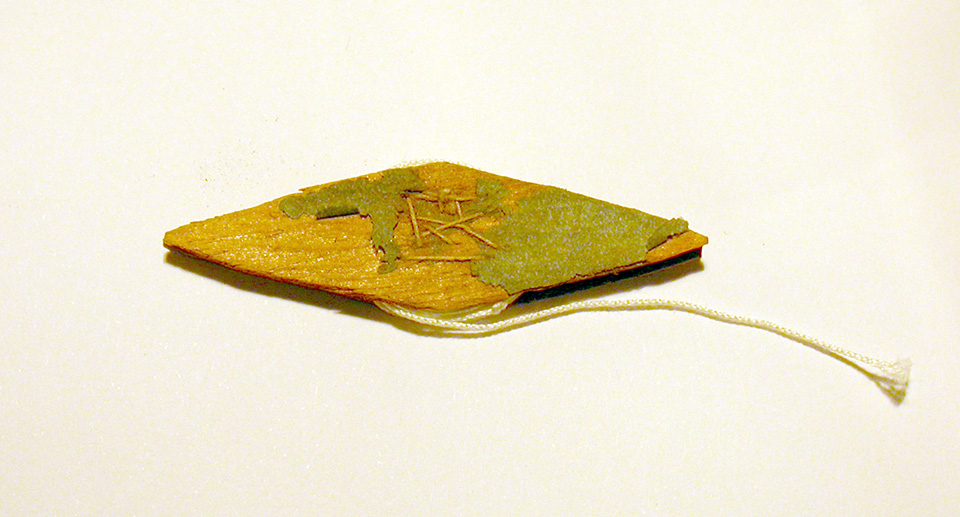

In addition to the pins, needles and reels associated with everyday sewing, there were also at least 20 items in the underfloor collection which demonstrate more specialised needlework. These included two crochet hooks, 10 elements from bobbins for lace-making, two [media]tatting shuttles and six other unidentified bone tools probably related to needlework. Most of this material came from Level 2, and is likely to be from the Immigration Depot women. They were equipped with sewing materials on board ship, both as training and to keep their hands busy, and they continued this work if they remained at the barracks for short periods of time. This needlework is likely to have been much finer, and more decorative, than the practical sewing of the asylum women.

Boots and shoes were supplied to the Destitute Asylum by outside contractors, but the archaeological remains of more than 470 leather [media]offcuts indicate that shoe repair was also carried out by some of the asylum women. While the repairs were often rough and ready, others show considerable skill. A well-preserved soft boot from the northern dormitory on Level 3, for example, has been carefully repaired to provide structure and flexibility. The boot was rebuilt using heavy cotton lining and black suede to reattach the leather toe, the upper and backstay. Wear patterns at the toe indicate that the shoe was [media]worn on the right foot, and it was fastened with 10 pairs of lace-holes at the inner ankle.

There is also archaeological evidence for hat-making. Dozens of strands of plaited straw from the cabbage-tree palm (Livistonia australis), and a palm-leaf shredding tool, were found on Level 3. The tool features eight small metal teeth inserted into a wooden handle, and was used to slice fibre into strips for weaving into hats or baskets. Hat-making began among convicts in the early settlement of Sydney, but by the mid-nineteenth century the hats had become very popular among both men and women, and good quality items were expensive. [5] The work was fairly simple and required few tools, and it became a cottage industry as well as a common form of institutional labour in the nineteenth century. There is no evidence that the hats were made for sale outside the asylum, and it appears from the location of the remains on Levels 2 and 3 that the work provided hats for women in both the asylum and the Immigration Depot.

Textiles and clothing

The clothing of working Australians in the nineteenth century has not been well documented, and that of institutional inmates even less so. [6] Clothing and textile fragments from the barracks, however, give some indication of what the asylum women were actually wearing. This material includes thousands of small fabric offcuts, along with garment components such as pockets, sleeves, cuffs and collars. The women were provided with a clean set of clothing when they entered the asylum, and their garments were washed every week in the laundry.

The women wore a kind of uniform, although this was not compulsory. Those in mourning, for example, were allowed to dress in black, and the archaeological material reveals some diversity in the fabrics and patterns used. Clothing generally consisted of a plaid (checked) dress and a cotton apron, along with chemises and petticoats, either plain or in purple cotton prints. Many of the women wore machine-knit [media]stockings of wool or cotton, most of which had been darned or repaired at some stage. Old dresses were sometimes altered and reused as warm petticoats. A number of fancy clothing items were found on Level 2, including lace collars and fingers from leather gloves. These items probably derive from immigrant women staying briefly in the dormitories.

Some of the items from the underfloor collection may also relate to the Irish female orphans who passed through the barracks from 1848 to 1852. Around 8,000 young women, aged mostly 14 to 17 years, were brought out to Australia from the workhouses of famine-struck Ireland, to meet the demand for domestic servants in the colonies. [7] More than half were sent to New South Wales, and many were accommodated on their arrival at the Hyde Park Barracks, where wards on the upper floors were made available for their comfort and protection. The Irish Poor Law Unions provided each young woman with clothing that included six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of shoes, two gowns, a shawl and a bonnet. [8] For most of the young women, this was probably the most complete set of clothing they had ever owned.

Conclusion

Archaeological material from the Hyde Park Barracks provides important insight into the lives of women who passed through the complex, especially the inmates of the Destitute Asylum. The items they lost, discarded or hid in the floor cavities speak directly of their work, health, leisure, clothing and religious convictions. We can use this material to read their lives from the inside out, where they exercised at least some control over their relations with each other and the institution as a whole.

While living conditions at the barracks were crowded and austere, there is little evidence of the worst excesses of contemporary industrial workhouses as in Britain and the United States. Regular medical care was available, food was monotonous but ample, and tobacco was given to all who wanted it. Some of the women received money or extra rations from the Matron for the work they performed. Books and religious tracts were brought in by clergymen, while private spiritual needs, especially among the Catholic women, were met with rosaries and devotional medals. Newspapers and other reading material were also available from a small library in the asylum. [9]

The Matron of the Immigration Depot and the Destitute Asylum, Lucy Applewhaite-Hicks, managed the women for almost a quarter of a century with a mix of firmness, efficiency and compassion. She and her family lived in quarters on Level 2 of the Barracks, and her eldest daughter served as sub-Matron. Their management ensured that the asylum was oriented not towards discipline and punishment, but to productive labour and support for the vulnerable. It was a permanent home for some of the inmates, temporary for most, but a vital refuge for all.

References

'Hyde Park Barracks Research Project', Archaeology Program, La Trobe University website, http://www.latrobe.edu.au/archaeology/hyde-park-barracks/index.html, viewed 25 October 2010

Notes

[1] Further details are available at 'Hyde Park Barracks Research Project', Archaeology Program, La Trobe University website,http://www.latrobe.edu.au/archaeology/hyde-park-barracks/index.html, viewed 25 October 2010

[2] Ralph Merrifield, The Archaeology of Ritual and Magic, BT Batsford, London, 1987, pp 128–36; Gerard P. Scharfenberger, 'Upon This Rock: Salvage Archaeology at the Early-Eighteenth-Century Holmdel Baptist Church', Historical Archaeology, vol 43, no 1, 2009, pp 12–29

[3] Penny Crook and Tim Murray, An Archaeology of Institutional Refuge: The Material Culture of the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, 1848–1886, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2006, p 58

[4] Sylvia Groves, The History of Needlework Tools and Accessories, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, United Kingdom, 1973, pp 60–61; WW Knox, Hanging by a Thread: The Scottish Cotton Industry c.1850–1914, Carnegie Publishing, Preston, Lancashire, 1995, pp 77–78

[5] Margaret Maynard, Fashioned From Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, p 170

[6] Margaret Maynard, Fashioned From Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, p 91

[7] BW Higman, Domestic Service in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002, pp 75–76; Patrick O'Farrell, The Irish in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1987, pp 74–78

[8] Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Orphans in Australia, The Genealogical Society of Victoria, Melbourne, 1991, p 89

[9] Joy N Hughes, 'Hyde Park Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women, 1862-1886: An Historical Study of Government Welfare for Women in Need of Residential Care in New South Wales', Master's thesis, School of Humanities, University of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2004, p 82