The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Barnett Levey's Theatre Royal

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Barnett Levey's Theatre Royal

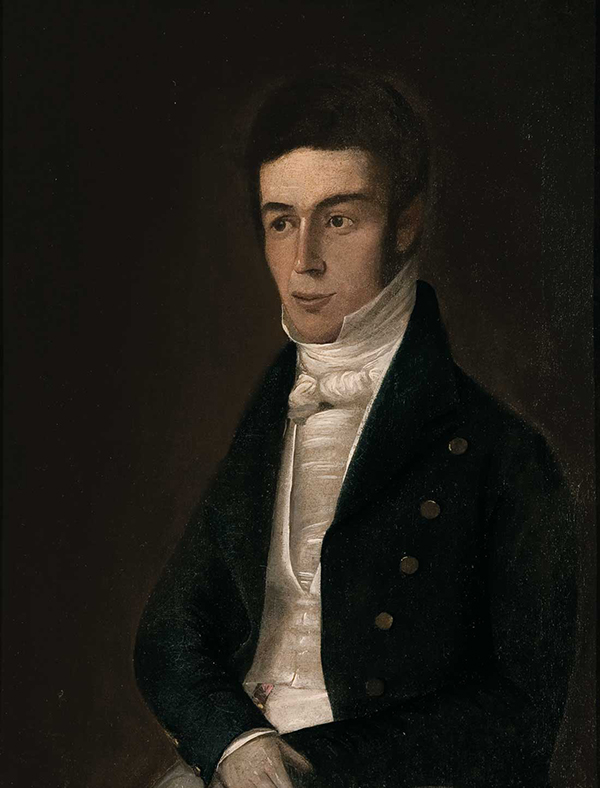

[media]For the first 40 years of settlement at Sydney Cove any theatrical venture had to have the governor's consent. Then in the late 1820s local entrepreneur Barnett Levey emerged as the leading figure in a long-running campaign against Governor Darling for permission to open a commercial theatre.

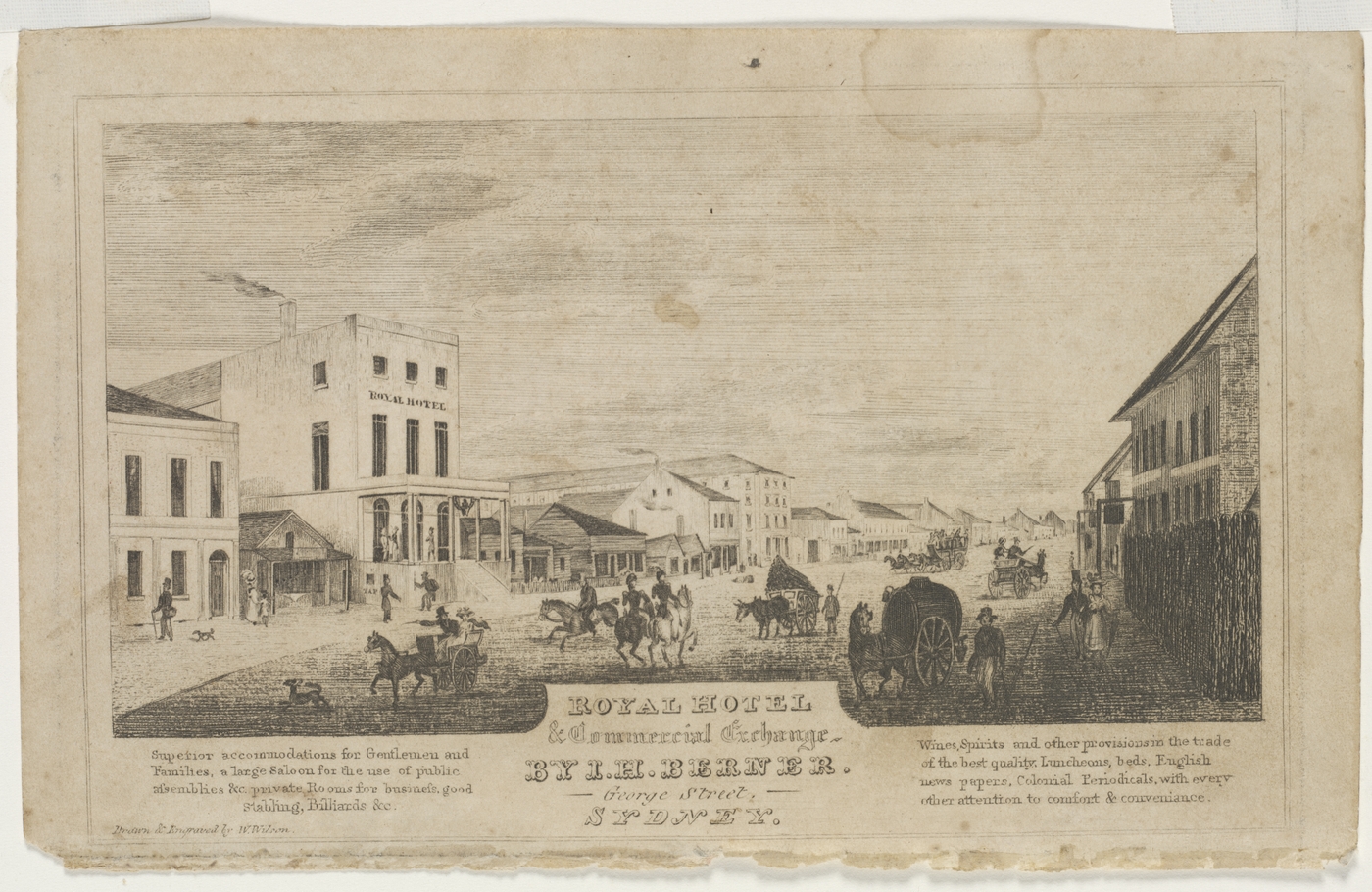

[media]These negotiations took place in a settlement without a purpose-built theatre, but Levey had a plan. Through his successful older brother Solomon, Levey had acquired a warehouse on George Street, roughly where the Dymocks building now stands. He had grand plans to expand this into his Colchester Warehouse, a five-storey complex, with a windmill on top and, inside, 'a large space for the purpose of dramatic representation'. Other entrepreneurial colonists thought Levey's grandiose building plans were suspect and there were few investors in the project. So he changed tactics. Levey converted the street front of his warehouse into a grog shop, which he styled the Royal Hotel, and opened several of the warehouse spaces as the Royal Assembly Rooms.

Descriptions of these Royal Assembly Rooms vary, but rough and ready, it was a rectangle about 90 feet (27.4 metres) long, with two tiers of boxes and a pit. The forestage had doors on each side, painted with portraits of the Muses. There was a green baize front curtain and a painted act drop showing steps leading to a distant temple. It was a theatre in all but name. One estimate is that it held about 700 people.

Levey announced a concert to be held in August 1829. The theatre was licensed and performances continued erratically for about a year. Then, to overcome falling returns, Levey tried to expand into his own solo 'at home' presentations, in the style popularised by the leading British performer Charles Mathews. It was too much. The governor threatened to revoke his licence and Levey did not go ahead.

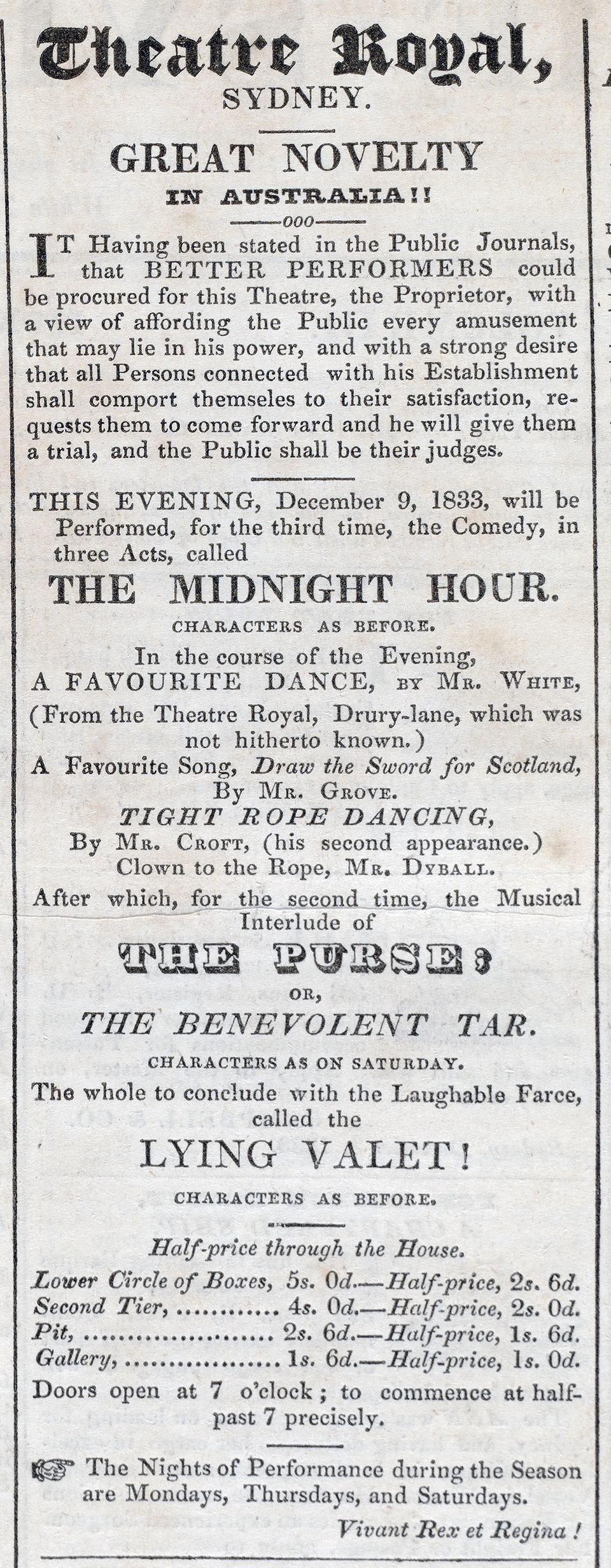

With the departure of Darling and the arrival of Richard Bourke, Levey again tried for permission and this time, in April 1832, he was granted a licence to present theatrical entertainments at his George Street site. Unfortunately by then he was bankrupt and no longer owned the building. The former mortgagee Daniel Cooper arranged to complete the theatre space and finish the hotel in the front. Levey, meanwhile, leased part of the building from the new licensee of the hotel, George Sippe. He called his area the Salon Royal, again set it up as a theatre and held a series of successful concerts, with himself as solo performer. After establishing a repertory company, [media]on Boxing Day 1832 he staged, in the same area, the popular British nautical melodrama Black Eyed Susan and the farce Monsieur Tonson – a picture of the Englishman abroad. The first night was a great success and business remained quite good.

It is unclear when the 'proper' theatre designed within the building was completed. This involved structural changes, including raising the ceiling to just under nine metres over the stage and raking the floor of the pit. The interior was decorated in green and gold, with mirrored stage doors, and an audience area of two tiers of narrow boxes and a gallery. The whole area was about 26 metres long.

Levey [media]finally reached an agreement with the owner Daniel Cooper to lease this theatre and opened his Theatre Royal on 5 October 1833 with his company playing the well-known melodrama The Miller and his Men and the even older farce The Irishman in London. The repertoire remained drawn from British popular standards, but Levey also organised the first professional performance of Shakespeare in Australia in his theatre – a production of Richard III on Boxing Day 1833.

[media]Initially business was good at the Theatre Royal. Unusually for the times, Levey promoted the dress circle as the best part of the house, and he charged from two to five shillings for seats. As a venue, however, it had its ups and downs. The pit was often the scene of disruption, and the cause of much complaint.

Levey, also, was not a particularly good businessman. He was quick-tempered and litigious and his liking for drink rapidly increased. The result was deterioration in discipline in the theatre, and there were quarrels with the actors over money. In 1835 Levey was forced to lease his theatre to a group of six businessmen. One of these, Joseph Wyatt, bought out the other partners in 1836 as the lessee. Levey returned briefly to the then failing theatre enterprise, and appears at this time to have also regained ownership of the building. But he died a year later. Wyatt then persuaded Levey's widow to sell him the building. Wyatt had plans for another theatre, so he closed the Theatre Royal. Two years later, in 1840, it was destroyed by fire.

References

Ian Bevan, The Story of the Theatre Royal, Currency Press, Sydney, 1993

Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1985