The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Western Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Western Sydney

From Cowpastures to pigs' heads

On 27 May 2008 Camden Council voted unanimously 'on planning grounds' to reject the Quranic Society's development application for a $19 million Islamic school in Cawdor. The school site is located in an area that colonial authorities originally referred to as The Cowpastures, after the surprise discovery of the First Fleet's herd of runaway cattle, by then magnificently multiplied in the fertile region. Believing that the Islamic school was a cultural incursion too far, Camden residents were triumphant at the turn of events in their campaign of cultural protectionism. Prior to council's decision, hostilities had been vocal, offensive and at times vicious with the late-night staking of two bloody pigs' heads at the school site, alongside an Australian flag. Upon their triumph one resident in particular claimed her 15 minutes of fame, declaring 'the ones that come here oppress our society, they take our welfare and they don't want to accept our way of life'. [1]

'The Macarthurs will be proud of us', she went on. But invoking the name of the Macarthurs, Camden's most historically prominent family, however, was clearly paradoxical. It was much to the chagrin of some of the Macarthur descendents, who in their rebuttal showed a depth of understanding and clarity that was all but missing outside Camden Council Chambers that night. 'No one can say what their reaction would have been', they wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald.

But we can say that they were first-generation Australians who sought to continue to honour their cultural heritage in a new place and valued education for their children. [2]

From the early colonialists to the contemporary settlement of refugees from north-east Africa and the Middle East, the socio-spatial development of Sydney's west is intertwined with the waves of first-generation Australians seeking to make a new life for themselves and their families in an often unsympathetic land, with an unfamiliar language and alien culture. Most first-generation Australians have sought to maintain their native tongue and aspects of their culture. Few, however, have managed to dominate an ancient land and culture quite as proficiently as Macarthur and his peers.

[media]Western Sydney is a region of great complexity: a patchwork of culture, language, ethnicity, personal histories, religion, income and status. This essay explores socio-spatial issues, urban governance and settlement patterns in an attempt to reveal some of the foundations contributing to the contemporary character of 'Western Sydney' as both spatially and culturally the 'other' Sydney. The interplay between internal and external forces has produced a region that is at once diverse and culturally rich, yet generally regarded as homogeneous and amorphous.

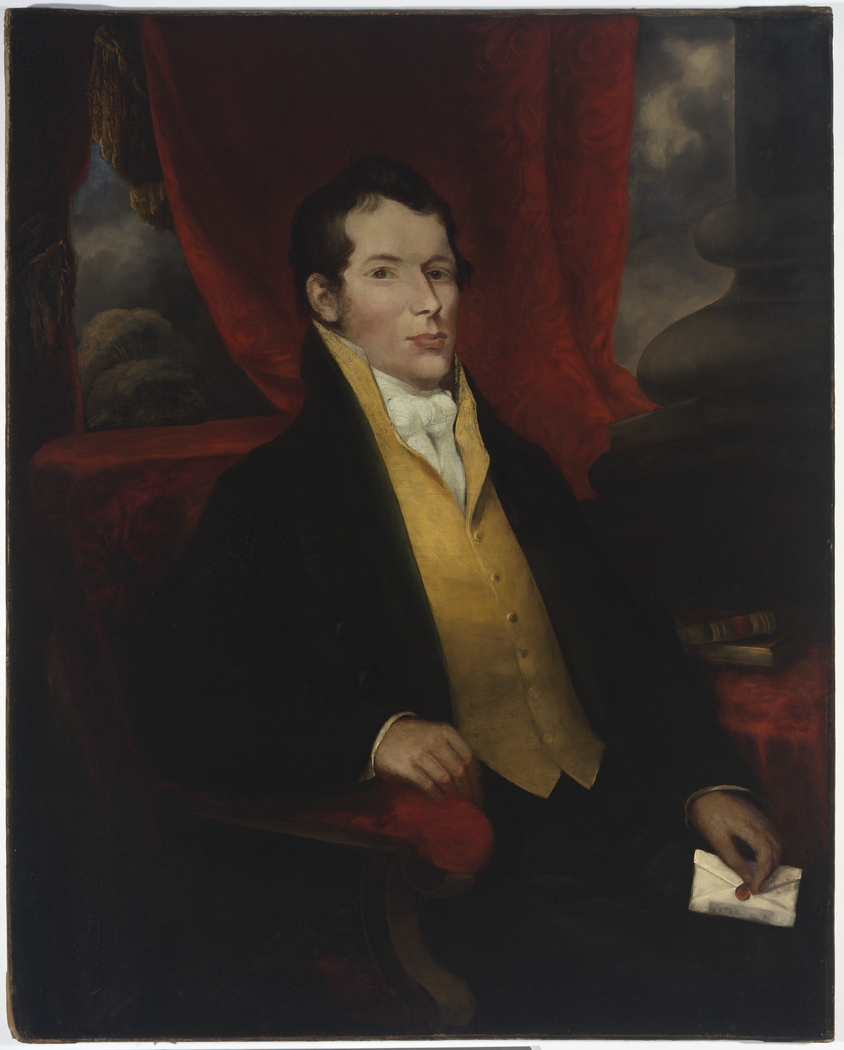

The first incursion

[media]John Macarthur (1767–1834) was a controversial character: a political activist, social climber, recipient of huge land grants, and so-called 'father' of the Australian wool industry. A ruthless lieutenant of the newly formed New South Wales Corps, Macarthur arrived in the New Holland penal colony on the Second Fleet with his wife Elizabeth (1766–1850) and a debt of £500. By 1800 he had apparently transformed the debt into a £20,000 fortune. Governor King assessed Macarthur as a man dedicated to 'making a large fortune, helping his brother-officers to make small ones'. [3] Macarthur, it seems, was the original Sydney speculator. In 1806 he took up a large land grant at Cowpastures for the purpose of sheep husbandry. By the 1830s the family had amassed an extensive convict labour force to work numerous farms, including the 27,333-acre (11,061-hectare) Camden Park, after which the township of Camden was later named. [4] Today, the Palladian-style Camden Park House and 960 acres (388.5 hectares) of the estate remain in the possession of Macarthur's descendents.

Camden Park remains a symbol of a colonial age when Anglo-Christian values, individualism and materialism succeeded in dominating an ancient land, its people and their totemic cultures. Since time immemorial the Gandangarra and Dharawal people had inhabited the Cowpastures of south-west Sydney. The initial, friendly curiosity of Aboriginal people towards the early Europeans inevitably developed into great antipathy and resistance, particularly around the Cowpastures, where clashes were frequent. For instance, on 17 April 1816, on a punitive expedition to track down 'hostile natives', Captain Wallis of the New South Wales Corps oversaw the massacre of 14 Dharawal people, including women and children, camping near Appin. [5] Within thirty years of European settlement, Aboriginal cultures within the Sydney basin were irretrievably altered, if not effectively extinguished.

In 2008, Camden locals called on their colonial narrative to support their claim to cultural protectionism. The narrative has provided the district with a distinct identity, protecting it culturally and spatially from the seeming ravages of more ethnically diverse neighbouring suburbs. A campaign advertisement by Wendy Underwood, a local resident, in the lead-up to the 2004 local government election, encapsulates the sentiment:

But most importantly, we are still a country community that cares, we have not got lost in the multicultural jungle – we have retained old-fashioned Christian values and will stand up for what is right. [6]

[media]Although Camden's contemporary attempts at preserving its cultural 'integrity' have been unusually intense, the historical development and character of Sydney's western suburbs is rooted in local and domestic struggles against successive waves of cultural incursion. What differentiates western Sydney's experience from other parts of Sydney, however, is that these struggles have taken place in a region distinctly disadvantaged in social and physical infrastructure, employment opportunities, educational and cultural facilities, and subject to place-based prejudice.

Sydney's western growth

In contrast to Melbourne, pre-World War I Sydney was a relatively dense, compact city, defined by the terrace and confined by the harbour and lack of adequate public transport. Prior to 1906 the lack of public transport was due in large part to the domination of the New South Wales parliament by rural interests. [7] Competition for housing pushed up rents, caused overcrowding and turned less salubrious areas like the Rocks, Balmain, Alexandria and Newtown into slums. Low density suburbs like Strathfield developed around city-centric railway lines to cater for bourgeois families. 'Western Sydney' comprised variously sized country towns and hamlets (of which Parramatta was the largest and most significant) clustered around transport routes and interspersed with farm holdings and bush. These towns were invariably controlled by and for the benefit of a handful of elite, usually Anglican, families and generally comprised both a Methodist middle class and a Catholic working class. This historical narrative is well recognised in the naming of local suburbs, parks and monuments, as well as in contemporary local histories and the permanent exhibitions of local and regional museums. The standard historical stories of the region typically fade out as they approach World War II. But the postwar period in fact, is when Western Sydney comes alive as a region of dynamic development and social significance.

Postwar 'Western Sydney'

The most intense period of development of Sydney's western suburbs commenced after World War II when demand for housing outstripped building supplies, and the need for industrial labour was met through postwar immigration programs. The western suburbs became the settling place for families subject to the inner-city slum clearance programmes, as well as lower income migrants. In the booming economy of the postwar period, rabbit-ridden paddocks between towns filled in rapidly with lower income private and public subdivisions.

[media]Services and basic infrastructure, like sewerage and curb and guttering, were generally an afterthought, if provided at all. The lack of public transport was premised on the expectation of car ownership, even though 20 per cent of households in western Sydney were still without a car in 1971. [8] The region was without a teaching hospital until the establishment of Westmead Hospital in 1978, although inequality in health care was not really confronted until the Wran government's bitterly fought 'beds for the west' campaign in the 1980s; and the region's only university was not established until 1989.

The shortage of construction material in the period meant that suburban housing was generally austere, cheaply constructed and frequently jerry-built. [media]Fibro cement became the most popular building material for working class homes, so that by 1971 some 179,379 fibro dwellings had been constructed in Sydney's 'fibro belt', in contrast to Melbourne's 20,297 dwellings. [9] The availability and low cost of the material encouraged both owner-building and easy extension.

[media]Some suburbs, like the 'planned estate' of Winston Hills in the north-west, were established specifically for middle class families. Larger, brick-veneer houses were built and services established from the outset. As historian Peter West notes, unlike other suburban developments, Winston Hills 'was fully serviced, with sewerage, parks and trees already supplied, as well as new shopping centres'. [10]

Coinciding with the rise of consumer society and the ensuing socio-economic cleavages that subsequent consumption patterns created, 'Western Sydney' from the outset signified low income, low education, homogeneity and disadvantage. Even today 'Western Sydney' continues to be conceptualised as some amorphous location and culture by the non-local news media and non-residents. Greater western Sydney stretches over nearly 9,000 square kilometres and 14 local council areas, and has a population of some 1.79 million people – 43.2 per cent of the Sydney metropolitan total. [11] In reality, it comprises socially and economically distinct sub-regions, each with its own urban issues.

Sub-regions of greater western Sydney

| Sub-regions of western Sydney | Local government area | Median household income $ | English spoken only % |

| South-west Sydney | Canterbury | 836 | 29.8 |

| Bankstown | 926 | 43.3 | |

| Fairfield | 873 | 25.5 | |

| Liverpool | 1,082 | 47.0 | |

| Outer south-west Sydney | Campbelltown | 1,066 | 72.0 |

| Camden | 1,353 | 88.5 | |

| Wollondilly | 1,186 | 90.7 | |

| Central western Sydney | Auburn | 906 | 22.0 |

| Parramatta | 1,043 | 48.8 | |

| Holroyd | 998 | 48.5 | |

| Outer western Sydney | Blacktown | 1,105 | 62.1 |

| Penrith | 1,147 | 81.7 | |

| North-west Sydney | Baulkham Hills | 1,732 | 72.5 |

| Hawkesbury | 1,146 | 90.1 | |

| Sydney (MSR) | 1,154 | 64.0 | |

| Australia | 1,027 | 78.5 |

(Source: ABS 2006 Census of Population and Housing: Community Profile)

'Westies' and cultural stereotyping

During the period of rapid suburbanisation, public intellectuals and artists, including Patrick White, Germaine Greer and Robin Boyd, carelessly branded utilitarian suburbs as places of dreariness and mediocrity. For entertainer Barry Humphries, working class suburbs became a subject of great mirth, and financial reward. The residents of western Sydney must still contend with this legacy. [media]One of the more debilitating status signifiers produced during this period was the 'Westie'. It was a term of division and derision, and became shorthand for a population considered lowbrow, coarse and lacking education and cultural refinement. The 'Westie' was a rhetorical device that designated the 'other' Sydneysider: spatially, culturally and economically different from the more prosperous and privileged Sydneysiders of the north and east. As one resident of Harrington Park in the Camden area explained, when asked how she felt about moving from Sutherland to the western suburbs:

A: I wouldn't call this the western suburbs. It's more rural. I wouldn't live in the western suburbs.

Q: Why not?

A: Well, they're a different type of person. [12]

[media]Derogatory labelling of residents of western Sydney was aided by the social problems and cheap aesthetic of large-scale, public housing estates developed in the 1950s at Seven Hills, followed by Green Valley and Mount Druitt in the 1960s, and the Radburn estates of Bonnyrigg, Villawood, Claymore, Minto, Airds and Macquarie Fields in the 1970s.

Public housing in Green Valley

Probably because of its scope, Green Valley came in for particular drubbing. Between 1961 and 1966 the population of the 'Valley' increased from 1,000 to 24,000, with British and native-born settlers predominating. This growth not only doubled the population of Liverpool, but injected a disproportionate number of financially and socially distressed households into the area, placing great pressure on the municipality's limited resources. [13] Although Housing Commission planners included parks, playing fields and other social infrastructure in the plans for Green Valley, it was left to the struggling local council to actually fund and construct these facilities. For outer urban councils it has been a game of 'infrastructure catch-up' ever since.

Green Valley brought a degree of notoriety to otherwise sleepy Liverpool. By 1966, about 60 per cent of the population of Green Valley was under 20 years of age. The mere concentration of such large numbers of youth in the area meant that 'delinquency' was an observable problem, and consequently newsworthy. The media unfairly dubbed the suburb 'Dodge City' in reference to the frontier mayhem of the American wild west. However, accusations of delinquency were not confined to Green Valley and Liverpool. Blacktown and Penrith were similarly afflicted, with stories of delinquency peppered through the local papers. [14]

During the 1960s, moral panics resulted in Sydney's western suburbs being viewed as the nursery for juvenile delinquency, and a rhetorical relationship developed around the ideas of delinquency, working class culture and the derogatory term 'Westie'. Arguably, the 'delinquency' problem was more an outcome of the emerging development of youth culture and media interest than of an association between place and behaviour. [media]The demonising of young people in Sydney's west continues into the twenty-first century, with media representations of ethnic gangs, car-loving hoons, mall rats and teenage mothers, not to mention the spurious belief that western suburbs youth are more prone to low literacy levels and attention deficit disorders.

Since the early 1980s, western Sydney's public housing estates have been particularly affected by successive Federal and State government policies of 'residualisation'. Rather than housing a mix of employed and welfare-dependent households – the social housing model – these estates accommodate stressed households contending with a number of health, social and economic issues. [media]A number of these estates, including Minto and Bonnyrigg, are currently being 'regenerated' through the introduction of private home ownership in the expectation of creating a 'social mix'. Rather than acknowledging the relationship between socio-economic structure and disadvantage, this policy continues to promote the causal relationship between poverty and geography that has categorised people in Sydney's west for decades.

'Wogs and Dagos'

Under the economic and defence-based policy mantra of 'populate or perish', some 2.5 million migrants, mainly from the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Malta, Italy, Greece and the former Yugoslavia, settled in Australia in the two decades following World War II. [15] Initially cheap rental housing, in conjunction with an established ethnic presence, in the declining inner suburbs of Alexandria, Leichhardt, Marrickville, Newtown and Enmore meant they served as first-stage settlement areas for postwar migrants, particularly from southern Europe. [16] From the 1960s, however, slum clearance and gentrification forced lower skilled migrants out to cheaper public and private housing in the new subdivisions of Sydney's west.

Yugoslavs, Germans, Austrians, Russians and Italians tended to settle in the Liverpool-Fairfield area where small ethnic concentrations, particularly of Italians, were already established. Maltese tended to concentrate around Blacktown, Greystanes, Holroyd and Fairfield, while Greeks displayed a more dispersed pattern of settlement in the suburbs, with a solid presence in Blacktown as well as the south-western suburbs between Kingsgrove and Bankstown. Poles settled in numbers in Bankstown and Parramatta. [17] Between 1947 and 1966 these suburbs experienced immense population growth and social restructuring (Table 2). By 1986 migrants comprised between 20 and 50 per cent of the population of these suburbs. [18]

Table 2: Population growth in specific local government areas between 1947 and 1966

| Local government area | Population 1947 | Population 1966 |

| Bankstown | 42,646 | 159,981 |

| Blacktown | 20,753 | 111,357 |

| Fairfield | 15,987 | 101,226 |

| Holroyd | 24,129 | 65,983 |

| Liverpool | 12,642 | 68,959 |

Source: P Spearritt and C Demarco, Planning Sydney's Future, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

[media]Apart from enhancing the variety of foodstuffs available and the contribution of the 'wog mansion' to an otherwise fairly bleak architectural landscape, southern European migrants did little to disturb the suburban status quo. Arriving in the period of assimilation, 'new Australians' were expected to conform to an indeterminate ideal of Anglo-Australian culture and values. Nevertheless they were looked on with suspicion by their Anglo neighbours. They were discouraged from becoming involved in community activities, and their children were harassed and bullied at school. It is hardly surprising that they generally kept to themselves and their expatriate networks.

These postwar migrants settled in Australia during an extended period of economic growth and an economy with an insatiable appetite for labour. Still, for many unskilled migrants from southern and eastern Europe settling in Sydney's west, moving beyond the proletariat proved difficult. As Ware argues of Melbourne, but with relevance to Sydney:

They start with a much greater disadvantage than merely being at the base of the ladder as the native-born proletariat were. Because of the vast difference between the education and occupational skills of southern European-born and even the most disadvantaged of the native-born the bottom rung of the ladder has effectively been removed. [19]

This has been a recurring experience for more recent low-skilled, non-English speaking migrants. For many, social advancement has been even further compromised by the industrial restructuring of the past 20 years and an unforgiving global economy. Inexplicably little recognition has been given to this issue. Migrants have generally been left to get on with 'it' – economic and social integration [20] – and any lack of achievement is likely to be viewed as either a cultural or an individual deficit.

Non-European migration and the multicultural neighbourhood

[media]From Federation in 1901 until 1973, the White Australia Policy and 'dictation test' restricted non-European migration. This policy was premised on the superiority of cultural homogeneity and the notion that some cultures, namely western European ones, were more amenable to assimilation. The overtly racist nature of assimilation was tempered from 1966 with the introduction of integrationist policies which supported ethno-cultural rights and organisation. [21]

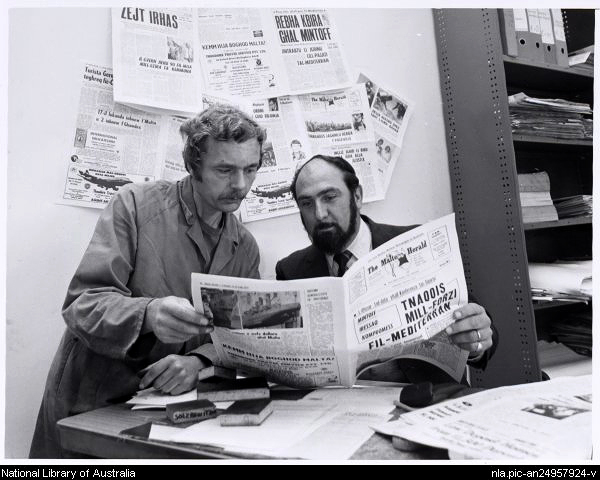

This laid the groundwork for the policy shift in the 1970s towards an 'ethnic group'-based model of multiculturalism. Although a positive move, such a model nevertheless denies the complexity and difference in 'ethnic' experience and identity. [media]Ethnic Communities Councils were established under the Whitlam Labor government of 1972–75, but it was the conservative Fraser government that followed which 'espoused the ideology of cultural pluralism' [22] on economic grounds, and supported this by permitting large-scale Asian and non-European migration.

This was in keeping with the history of Australia's postwar immigration program, which has invariably been a history of 'labour migration'. With unfortunate economic timing, the mass entry of low-skilled, impoverished migrants from south-east Asia and the Middle East commenced on the cusp of a period of global restructuring. This period was witness to economic deregulation, industrial reorganisation, a retargeting of government expenditure and a contracting welfare state. This has resulted in the formation of certain ethnic communities of structural deprivation, particularly in south-west Sydney.

Arguably, the two migrant groups which have most challenged suburban life are the Indochinese and people from the Middle East, many of whom arrived as refugees, usually under harrowing circumstances. The first Vietnamese refugees entered Australia in 1975 in the wake of the Vietnam War and unification under the communists. From their migrant hostels they moved out to nearby suburbs like Bankstown and Cabramatta, and began challenging the notion of what it was to be Australian. They unwittingly confronted the suburban status quo through their concentrated settlement patterns, Asian appearance and languages, temples, religious festivals and non-English shop signage, a particularly sensitive issue in Sydney's west in the 1980s. There are great stories of social mobility and economic success. Nevertheless, a disproportionate number of Indochinese have experienced 'mobility blockage' for a range of reasons – incongruous employment skills, language difficulties, and in some cases employee exploitation. The psychological impact of their dislocation experience may also have been a factor. [23]

Although Lebanese migrants, particularly from the Christian north, have been settling in Australia since the mid-1800s, civil unrest in Lebanon during the 1960s and 1970s caused a spike in migration, particularly amongst Muslims entering Australia through the family reunion stream. A generally unskilled group, they arrived in a deindustrialising economy. Lebanese migrants and their offspring are today disproportionately concentrated amongst the poor and low-income families of Sydney. [24] Their concentration within the western suburbs of Lakemba, Greenacre, Punchbowl, Bankstown, Auburn and Harris Park, in conjunction with their dress, language, shops and mosques makes them a visible minority within the wider community. [25] Racism is a major force in the lives of Lebanese Australians and particularly for young, second-generation Muslim men. In the classic intersection of minority ethnicity, age and gender, a proportion of these youth have responded by adopting a type of 'ethnic masculinity'. According to Poynting, Tabar and Noble,

this involves asserting what for them constitute their Lebaneseness in Australia, and doing so with a good deal of male aggression, often directed at authority figures from the 'mainstream' culture which are implicated in institutional racism. [26]

Problems involving young Muslim men tend to be viewed from a cultural or ethnic perspective, ignoring their social, political and economic disadvantage and exclusion.

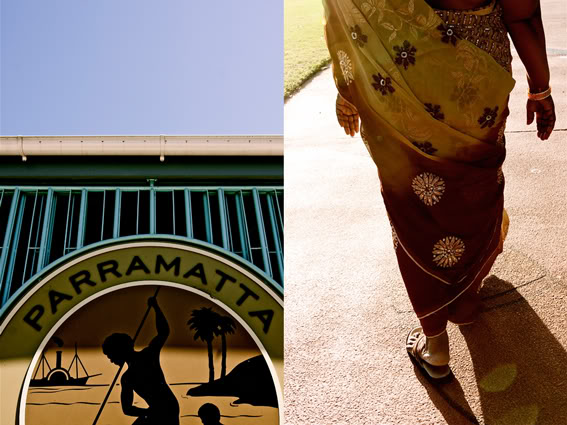

Throughout Sydney's history of migration, migration settlement patterns remain: better skilled, more highly resourced ethnic groups settled in Sydney's comfortable northern and eastern suburbs; while less skilled, poorly resourced migrants have made their homes in the suburbs of west and south-west Sydney. [media]Nevertheless, the vibrancy of western suburbs like Cabramatta, Bankstown and Auburn are a tribute to migrants' resilience and courage in surmounting the financial, emotional and cognitive difficulties of a foreign land, language, education system and culture.

The 'Aspirationals'

It's started to change Ingleburn to a Cabramatta type place. And the same thing in Liverpool. Once they get an influx it's like it changes the outlook of the place. Hurstville is a prime example. It used to be a beautiful place, but it's changing. It's going down the tubes the way it is going with all the shops that are around. It makes the area look grubby, dirty, unclean. [Male resident of Camden local government area who had recently moved from Ingleburn.] [27]

Towards the end of the 1980s, a subtle shift in institutional support for multiculturalism began occurring. The Fitzgerald Report [28] on immigration was critical of the selection criteria in immigration policy, and emphasised some dangers of multiculturalism to social cohesion. Immigration was reduced, and cuts were made to multicultural programs on the grounds of economic rationalism. This development intensified with the Howard Liberal government's visible withdrawal of commitment to multiculturalism, particularly after the rise of One Nation, a political party that fostered popular hostility to Asian immigration and multiculturalism. It was during this 'post-multicultural' period that a constituency of Anglo-Australian residents variously dubbed 'Howard's Battlers' and 'Aspirationals' began decamping from the multicultural suburbs of Sydney's west and southwest, to settle in homogenous residential enclaves on the 'new' urban fringe.

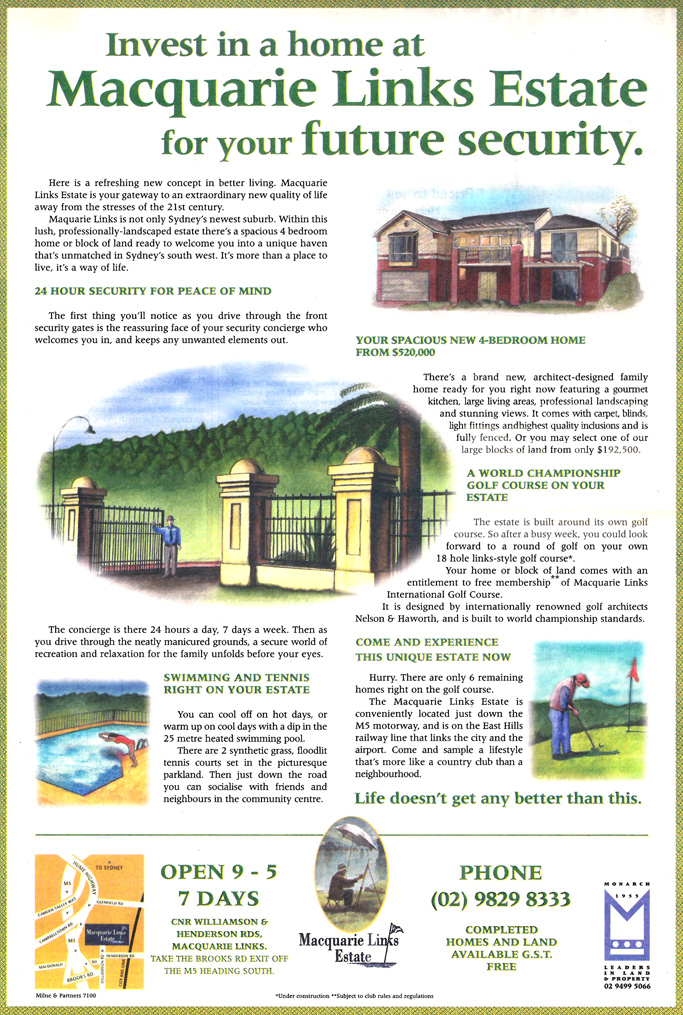

The term 'Aspirationals' came to prominence in the late 1990s to describe a seemingly new political constituency living in new middle-income estates on Sydney's urban fringe. Sydney's aspirationals are mostly 'Westies', just all grown up and taking advantage of dual incomes, easy finance and housing-based wealth. The master-planned communities they live in promote a particular ideological form of community, one which is used to buttress residents' social, physical and economic security in a variable and changing region like western Sydney. [media]Research into the decisions of residents to move into master-planned communities in Camden local government area indicates that their desire to move away from multicultural suburbs was merely one push factor, although a significant one. [29] They also wanted to move away from low-income neighbourhoods and disorderly public housing estates; they expected that buying into a new, economically and culturally homogeneous estate would better protect their property value; they wanted to move into a neighbourhood 'reminiscent' of their own Anglo-Celtic childhood, and to exhibit status and success through residential exclusivity. As one Camden resident explained when asked what motivated his purchase in Garden Gates:

It was a nice new estate. The houses appeared to be of a similar size. Large houses. There were no housing commission problems out here, because it's away from all that.[30]

The development of higher income 'Aspirational' areas in western Sydney indicates the strengthening of socio-spatial polarisation at both regional and local scales within Sydney. It can be argued that the economy and social fabric of western Sydney is strengthened by a mix of incomes, job types and employment opportunities, to ensure that it retains its talent, knowledge, creativity, wealth and established social networks, and can offer the range of social, cultural and economic opportunities that the rest of Sydney takes for granted. Nevertheless, such a perspective must rest on an understanding of the structural and spatial disadvantage that affects certain social groups and areas of western Sydney and on an agenda that supports lower socio-economic and marginalised social groups in their attempts to realise full social citizenship.

A region of diversity and complexity

It is remarkable that a disparate region like western Sydney, with its social complexity, pockets of social disadvantage and high concentrations of first and second generation migrants, has in the main been able to maintain a sense of stability and social cohesion. [media]Until recently, the development of western Sydney, with its low density and detached housing, in conjunction with the systematic release of land on the fringe for lower income, residential development, has worked to alleviate suburban pressure points and population displacement. Since the mid-1990s, however, this equation has been disrupted by the scarcity of new land releases despite continuing population growth primarily from migration. Other factors have included the displacement of first-home-buyer subdivisions on the urban fringe with higher income master-planned communities, the residualisation of public housing, and the lack of creative policies and support for low-income migrants that might enable them to claim a meaningful part of Australia's 'booming' economy.

Over the next 25 years, western Sydney is expected to receive 400,000 new residential dwellings; 160,000 new homes in greenfield sites in the north-west and south-west sectors, and the rest from urban renewal and densification programs in existing suburbs. Such growth will inevitably increase pressure on local and regional social and physical infrastructure, as well as intensify socio-economic and cultural reorganisation. Policy makers, planning strategists and government treasurers must heed the lessons of western Sydney's postwar development, to ensure social cohesion amongst disparate groups as well as a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunity. [media]With regard to equitable distribution, they could start, for instance, by questioning the social outcomes of the 'Plan for Sydney's Future' [31] which supports the strengthening of high-tech employment opportunities in Sydney's 'global arc' from Macquarie Park to Sydney Airport, while Sydney's 'utilitarian' west must be satisfied with the release of more industrial land. They should also rethink the ludicrous decision to ‘defer’ the construction of the south-west and north-west rail links through the region’s growth centres. Planning decisions like these inevitably entrench the perception of 'Western Sydney' as a low-skilled, lower socio-economic region, which has consequences for public and private investment and for the lived experience of residents of Sydney's west.

References

D Burchell, Western Horizon: Sydney's Heartland and the Future of Australian Politics, Scribe, Melbourne, 2003

J Collins, 'From Beirut to Bankstown: The Lebanese Diaspora in Multicultural Australia', in P Tabar (ed), Lebanese Diaspora: History, Racism and Belonging, Lebanese American University, Beirut, 2005, pp 187–212

G Gwyther, 'Once Were Westies', Griffith Review: Cities on the Edge, 20, 2008, pp 153–164

K Mee and R Dowling, 'Tales of the City: Western Sydney at the End of the Millennium', in J Connell (ed), Sydney: The Emergence of a World City, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, pp 273–291.

D Powell, Out West: Perceptions of Sydney's Western Suburbs, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards NSW, 1993

P Spearritt and C Demarco, Planning Sydney's Future, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

Notes

[1] McCulloch cited D Murphy, 'Am I the new Pauline Hanson? I hope so', Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 2008, p 1

[2] H Finlay and Macnell family, Letter to the Editor, Sydney Morning Herald, 2008, p 12

[3] K Buckley and T Wheelwright, No paradise for workers: Capitalism and the Common People in Australia 1788–1914, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1988, p 36

[4] A Atkinson, Camden: Farm and Village Life in Early New South Wales, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1988

[5] V Fowler, Massacre at Appin 1816, Campbelltown and Airds Historical Society Inc Campbelltown, 2005

[6] Camden Advertiser, 17 March 2004, p 15

[7] L Frost, 'Suburbia and Inner Cities' in A Rutherford (ed) Populous Places: Australian Cities and Towns, Dangaroo Press, Sydney, 1992, pp 190–197

[8] P Spearritt and C Demarco, Planning Sydney's Future, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1988

[9] P Spearritt, 'Statistical Tables' in J Davidson (ed), The Sydney – Melbourne Book, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1986

[10] P West, A History of Parramatta, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst NSW, 1990

[11] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 Census of Population and Housing: Community Profile at http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/Home/census 2007 and Office of the Minister for Western Sydney, About Western Sydney, at http://www.westernsydney.nsw.gov.au, accessed 10 July 2008

[12] G Gwyther, 'Paradise Planned: Community Formation and the Master Planned Estate', PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney, 2004

[13] T Brennan, New Community: Problems and Policies, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1973

[14] P West, The Secret Lives of Men: Growing Up in Penrith 1920–1992, University of Western Sydney, Nepean, 1992, p 56

[15] P O'Farrell, The Catholic Church and Community: An Australian History, NSW University Press, Kensington, 1992

[16] A M Tamis, An Illustrated History of the Greeks in Australia, Darsalis Archives of the Greek Community, La Trobe University, Melbourne, 1997 and J Collins, K Gibson, C Alcorso, S Castles and D Taid, A Shop Full of Dreams – Ethnic Small Business in Australia, Pluto Press Australia, Sydney, 1995

[17] P West, A History of Parramatta, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, Sydney, 1990

[18] G Karskens, Holroyd: A Social History of Western Sydney, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1991

[19] H Ware, 'The Social and Demographic Impact of International Immigrants on Melbourne: A Study of Various Differentials' in I H Burnley (ed), Urbanisation in Australia: The Postwar Experience, Cambridge University Press, London, 1974, pp 185–199, p 198

[20] P West, A History of Parramatta, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, Sydney, 1990

[21] S Castles, M Kalantzis, B Cope and M Morrissey, Mistaken Identity: Multiculturalism and the Demise of Nationalism in Australia, Pluto Press Australia, Sydney, 1988

[22] S Castles, M Kalantzis, B Cope and M Morrissey, Mistaken Identity: Multiculturalism and the Demise of Nationalism in Australia, Pluto Press Australia, Sydney, 1988 p 65

[23] G Y Lee, 'Indochinese Refugees Families in Australia: A Multicultural Perspective', Cultural Diversity and the Family: Volume 3, Ethnic Affairs Commission of NSW, Ashfield, 1997

[24] J Collins, 'From Beirut to Bankstown: The Lebanese Diaspora in Multicultural Australia' in P Tabar (ed), Lebanese Diaspora: History, Racism and Belonging, Lebanese American University, Beirut, 2005, pp 187–212

[25] J McKay, Phoenician Farewell: Three Generations of Lebanese Christians in Australia, Ashwood House Academic, Melbourne, 1989

[26] S Poynting, P Tabar and G Noble, 'Representations of Youth in Sydney: A Critique of Liberal Rhetoric about Young Lebanese Immigrants' in P Tabar (ed), Lebanese Diaspora: History, Racism and Belonging, Lebanese American University, Beirut, 2005, p 213–249

[27] G Gwyther, 'Paradise Planned: Community Formation and the Master Planned Estate', PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney, 2004

[28] Committee to Advise on Australia's Immigration Policies, Immigration: A Commitment to Australia Australian Government Publishing Services, Canberra, 1988

[29] G Gwyther, 'Paradise Planned: Community Formation and the Master Planned Estate', PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney, 2004

[30] G Gwyther, 'Paradise Planned: Community Formation and the Master Planned Estate', PhD thesis, University of Western Sydney, 2004

[31] NSW Department of Planning, Metropolitan Strategy: Cities of Cities, A Plan for Sydney's Future Sydney, 2005

.