The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Surprize

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Surprize

The [media]convict ship Surprize sailed to Australia in January 1790 in company with the Second Fleet transports Neptune and Scarborough.

Three other ships, the female convict ship Lady Juliana , the storeship Justinian and the Royal Navy supply ship HMS Guardian, sailed from England separately between July 1789 and January 1790, but all six vessels reached Port Jackson in June 1790 and came to be known as the Second Fleet. Because Surprize, Neptune and Scarborough had the highest mortality rate in the history of penal transportation, it was later known as 'The Death Fleet'. [1]

Built in Shoreham, West Sussex, 10 years before its voyage to Australia, the 400-ton [2] Surprize. Surprize was owned by slave traders Camden, Calvert & King who charged per head for each convict embarked, regardless of the state in which they arrived. The other convict transport of the Second Fleet, Lady Juliana, was chartered by First Fleet contractor William Richards junior and experienced a much lower death rate. [3]

For the voyage to Australia, Surprize sailed with about 254 convicts. [4] The ship had a crew of around 40 men, and was initially commanded by Donald Trail, a Scot and former navy master who had been employed by Camden, Calvert & King for some years. Prior to departure, Trail was moved to the command of Neptune, and replaced on Surprize by Nicholas Anstis. [5] The voyage was Anstis's second to New South Wales – he had sailed with the First Fleet as first mate on the transport Lady Penrhyn.

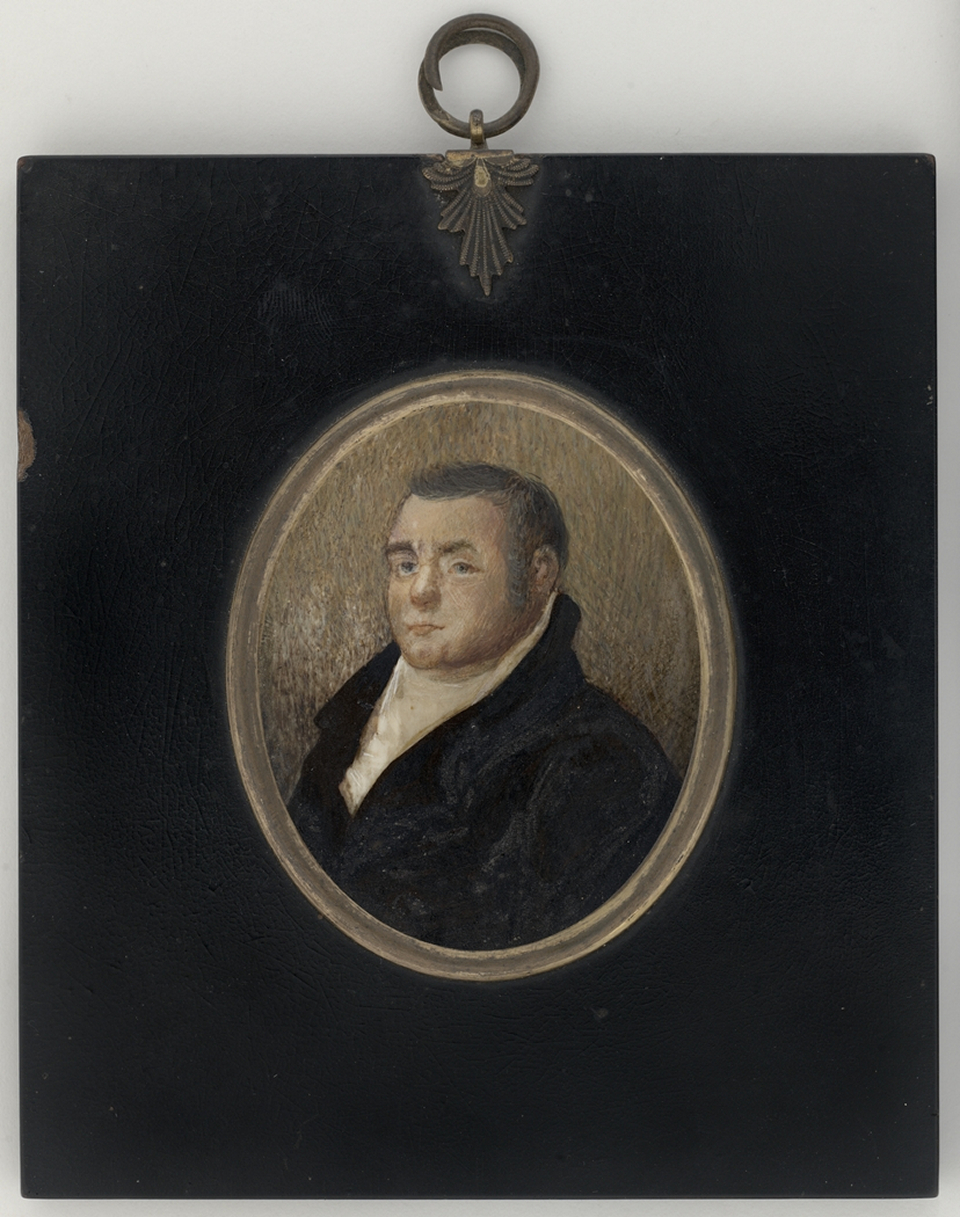

[media]Also onboard were surgeon William Waters [6] and two captains, a surgeon's mate, a lieutenant, a corporal, a drummer and 23 privates [7] of the New South Wales Corps who were part of two companies [8] replacing the marines who had sailed with the First Fleet. John Harris, the surgeon's mate, went on to play a key role in the development of the colony as a landholder and in a variety of military and administrative positions. [9]

The three ships were loaded with stores of flour, salt beef and pork, and on 17 January 1790, Surprize sailed from Portsmouth in company with Neptune and Scarborough. [10]

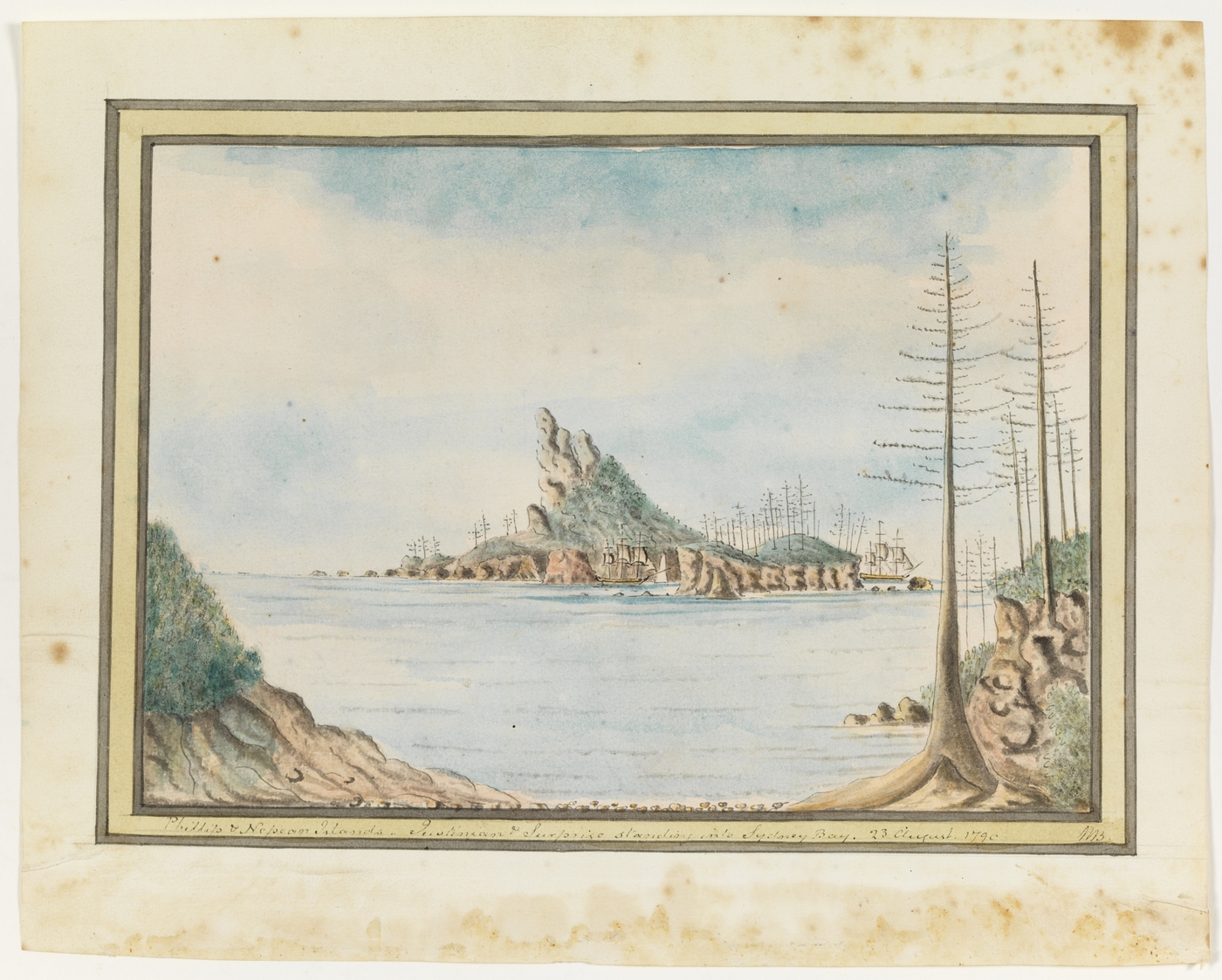

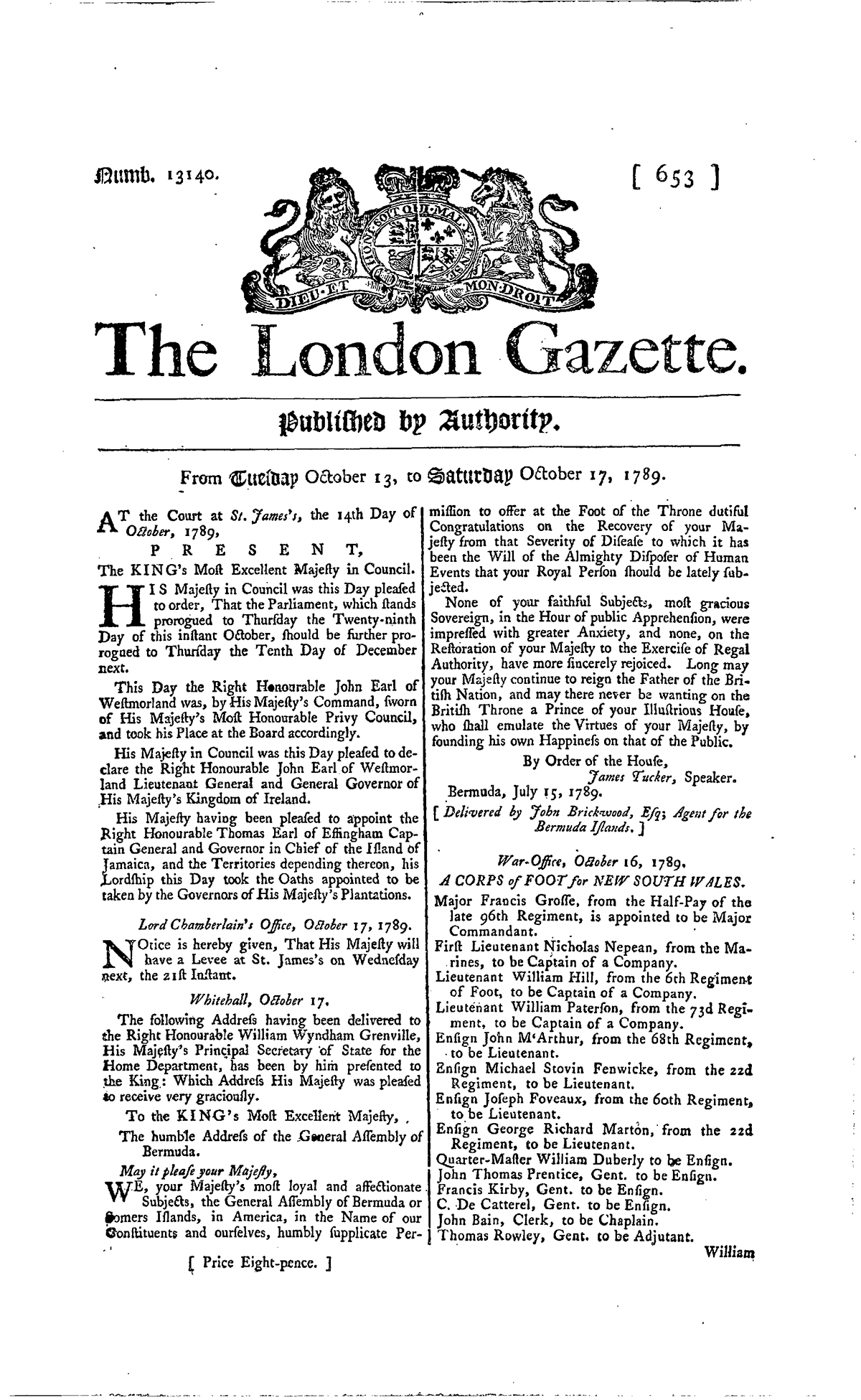

[media]The ships crossed the equator on 25 February and reached False Bay, Cape Town, on 13 April after a voyage of 86 days during which eight of Surprize's convicts died. [11] Tensions between two of the officers on board, Captain William Hill and Ensign John Thomas Prentice, culminated at False Bay with the arrest of Hill. [12]

Surprize reached Sydney Cove on 26 June 1790. Scarborough and Neptune arrived two days later. [13] As the three ships began to disembark their cargo of malnourished and sickly convicts, the extent of the convicts' mistreatment became clear. Of the approximately 1,000 convicts who had embarked from England on the three ships, over a quarter had died. On Surprize, one soldier and 36 convicts had perished during the voyage, and 126 required hospitalisation on arrival, [14] with many dying in the months after disembarkation. John Hindley, transported on Surprize for stealing, was buried at Sydney Cove on 7 September 1790, less than three months after landing.

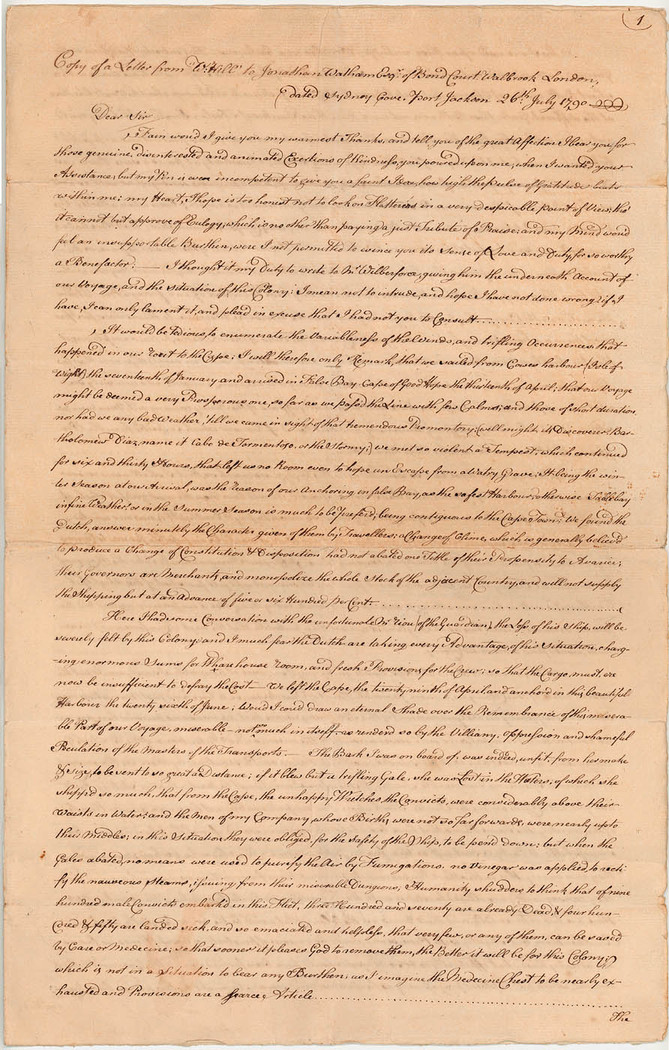

William Hill [media]of the New South Wales Corps, who sailed on Surprize, observed that during the voyage, convicts' rations had been withheld so that the food could be sold at a profit by several of the masters of the transports upon their arrival in Sydney Cove. The excessive use of irons and restricted movement contributed to the convicts' ill health during the voyage, made worse on Surprize by the leaky ship's tendency to take on water:

The Bark I was onboard of, was indeed unfit from her make and size, to be sent such a great distance; if it blew but a trifling Gale… the convicts were considerably above their waists in water. [15]

Surprize sailed from Sydney Cove on 1 August for Norfolk Island, transporting provisions as well as 35 male and 150 female convicts, two superintendents and one deputy commissary. The arrival of Surprize, in addition to the storeship Justinian, was met with gratitude and relief at the isolated settlement. Marine Ralph Clark wrote of his joy at seeing the familiar face of Surprize's master Anstis, whom he knew from the voyage of the First Fleet. [16]

Surprize left Norfolk Island for Canton on Sunday 29 August, arriving on 26 October 1790. The five remaining ships of the Second Fleet all followed, arriving in Canton in stages over the next month. Here they were loaded with a cargo of tea to freight home for the East India Company. Surprize returned to England in early September 1791. [17]

Despite their terrible experience on the Second Fleet, many of the convicts survived to complete their sentences and, along with their descendants, went on to make significant contributions as citizens of the colony. Surprize convict Joseph Wilson became one of the first emancipist settlers in the Hawkesbury River district when he received a land grant of 30 acres (12 hectares) in 1794. Thomas Higgins, son of a Surprize convict of the same name, was the first permanent settler in the Hornsby Valley. James Morley, sentenced to transportation on board Surprize for theft, became a partner in a shipping firm that transported goods between Sydney and the Hawkesbury and later operated a Sydney timberyard. Edward Merrick, also transported on Surprize for theft, became a successful farmer with a number of land grants and later reached the position of District Constable and Poundkeeper at North Richmond.

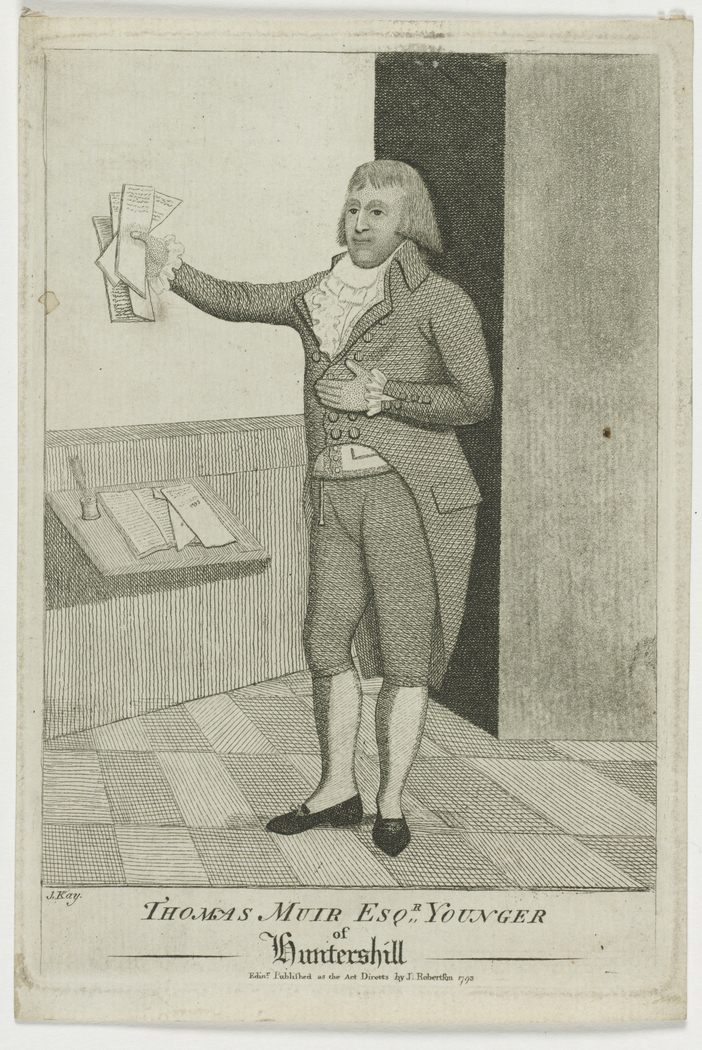

Surprize [media]made a second voyage to Australia as a convict ship in February 1794. Among the ship's convict cargo for this journey was famous Scottish political prisoner Thomas Muir whose farcical trial, transportation and subsequent escape to America in 1796 caused a sensation. [18] Surprize was later employed as a slave ship and merchant ship and in 1799 reports surfaced that the ship was captured by the French Frigate La Forte in the Bay of Bengal during the French Revolutionary Wars. [19] The ship's entry in the Lloyd's Register the following year confirmed its status as captured. [20]

Further reading

Bateson, Charles. The Convict Ships, 1787–1868. Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1969.

Collins,David. An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher. Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975.

Flynn, Michael. The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001.

Notes

[1] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 1

[2] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 30

[3] Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868 (Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1969), 20

[4] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 46

[5] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 30

[6] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 44

[7] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 129

[8] Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1987), 105

[9] BH Fletcher, 'Harris, John (1754–1838)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/harris-john-2164/text2773, published in hardcopy 1966, viewed 15 December 2015

[10] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 32

[11] Siân Rees, The Floating Brothel: The Extraordinary Story of the Lady Julian and its Cargo of Female Convicts Bound for Botany Bay (Sydney: Hodder Headline Australia, 2001), 191

[12] Elizabeth Macarthur, journal entry, in Some Early Records of the Macarthur's of Camden, edited bySibella Macarthur Onslow (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1914), 13

[13] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, volume III, 1798, edited by H Fletcher (Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975), 129

[14] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 46

[15] William Hill, letter to Jonathan Wathen, 26 July 1790 (copy), Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6821, available online at http://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=402753

[16] Ralph Clark, Journal and letters 1787–92, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, Safe 1/27a, b, online at http://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/s/search.html?collection=slnsw&meta_e=410289, 156

[17] Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim Convict Armada of 1790 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 2001), 52

[18] John Earnshaw, 'Muir, Thomas (1765–1799)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/muir-thomas-2488/text3347, published in hardcopy 1967, accessed 17 December 2015

[19] Northampton Mercury, 3 August 1799, 3

[20] Lloyd's Register for Shipping the Year 1800, printed by HL Galabin, 1799 (London: The Gregg Press Limited, nd)

.