The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Reserve Bank of Australia Building, 65 Martin Place, Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

A new beginning

[media]In January 1960 the Reserve Bank of Australia commenced operations as the nation’s central bank with Dr HC Coombs as its first Governor. It was formed by the Reserve Bank Act 1959, which separated the central banking role of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia from its commercial functions. The legislation mandated that the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Commonwealth Banking Corporation should have separate head offices, and plans were developed for the Reserve Bank’s new headquarters in Martin Place Sydney, between Macquarie and Phillip Streets. Coombs appreciated the symbolic importance of this and took the opportunity to establish a distinct public profile for the Reserve Bank in order to ensure public recognition and confidence in the institution.[1]

The significance of Martin Place

[media]The Reserve Bank building faces Martin Place, a space that has historically been the centre of Sydney’s banking and commercial district. Institutions such as the Australasia Bank, the Sydney Stock Exchange, the Colonial Bank, the Rural Bank of New South Wales, and later the National Australia Bank and Westpac have all established offices there at various times. The building that housed the headquarters of the Bank’s predecessor as Australia’s central bank, the Commonwealth Bank at 42 Martin Place, is one of the most prominent buildings in the precinct. These institutions have been crucial to the functioning of Australia’s banking system and its economy.

At its eastern end Martin Place meets Macquarie Street – Sydney’s premier civic boulevard. Public institutions, such as the New South Wales Parliament, the Supreme Court and the State Library of New South Wales define the character of Macquarie Street as a civic, democratic precinct. Traditionally, these institutions have been of national as well as state significance. The Parliament of New South Wales was the nation’s first elected legislature. As the residence of the Governor of New South Wales, Government House has served as the symbol of an enduring government office in Australia, and the law courts on Macquarie Street are the location for the High Court of Australia’s sitting in Sydney. The State Library of New South Wales traces its origins to the first public library established in Australia.

[media]The positioning of the Reserve Bank of Australia at the junction of Martin Place and Macquarie Street borrows associations from both spaces. The Bank’s position on this site complements its identity as an organisation that is central to the functioning of the Australian economy, but also an institution that represents the interests of the Australian people and remains accountable to them.

A modern building

[media]The Reserve Bank building was designed in 1959 by the Commonwealth Department of Works. The working group assigned to the project undertook an extensive study tour of Europe and North America to familiarise themselves with the premises of the Bank’s international counterparts as well as contemporary trends in commercial architecture.

The design team for the building comprised Clive D Osborne, Director of Architecture, Richard M Ure, Chief of Preliminary Planning, George A Rowe, Supervising Architect, and Fred J Crocker, Architect in Charge, with advice from Henry Ingham Ashworth, the Professor of Architecture at the University of Sydney, who was consulting during the same period on the Sydney Opera House’s progress.

[media]Construction began in 1961, and by the end of 1964 the building reached its full height of 80 metres above the street. The building totals 20 floors, together with a mezzanine and three basement levels. At its summit, it is surmounted by an observation lounge in the form of a lean pavilion. Extensions to the building were made between 1974 and 1980.

[media]Pre-war bank buildings invoked the qualities of strength, stability and solidity by employing heavy granite and trachyte stonework in the podiums and pillars, and the use of dark marble in their foyers. The 1916 building that housed the Reserve Bank’s predecessor, the Commonwealth Bank, towards the western end of Martin Place typified this style.

The Reserve Bank’s architecture aimed to embody a different set of values from those of earlier banks in Martin Place, replacing solidity with the associations of transparency. The building’s fenestration and glass curtain wall avoided the load-bearing role usually played by the pillars and walls of the traditional bank, admitting daylight and uninterrupted views of the banking chamber from the street. The use of light materials for interior surfaces such as aluminium and white marble complemented this open, light aesthetic. The minimal use of ornamentation and sleek, lean architecture conveyed a sense of efficiency and modernity. The transparency of the foyer in its interface with the public domain of Martin Place was analogous with the democratic accountability of the Reserve Bank as a public institution.[2] The Bank’s Governor, Dr HC Coombs remarked that:

‘The massive walls and pillars used in the past to emphasise strength and permanence in bank buildings are not seen in the new head office. Here, contemporary design and conceptions express our conviction that a central bank should develop with growing knowledge and a changing institutional structure and adapt its policies and techniques to the changing needs of the community within which it works.’[3]

[media]The national mandate of the Reserve Bank consciously informed the design of the building. A publicity brochure celebrating the completion of the building proudly announced that:

‘This…is a building having both national and civic importance. In its construction, materials and equipment of Australian origin have been used wherever possible.’[4]

[mediaThis preference was expressed in a multitude of forms. A variety of types of Australian stone were carefully selected from different states: Wombeyan grey marble and Narrandera granite from New South Wales, Ulam marble from Queensland, Footscray basalt from Victoria and black granite and slate from South Australia.[5] The timber finishes within the building were completed with local timbers such as Jarrah, Black Bean, Tallowwood and Tasmanian Blackwood.[6] The prosperity that wool had traditionally yielded for the Australian economy inspired its use in the building’s carpets and upholstery. The thoughtful use of this range of high quality Australian materials was unusual among comparable office buildings of the period.[7] Their incorporation into the building’s finishes was intended to represent confidence in Australian industry, creativity and craftsmanship.

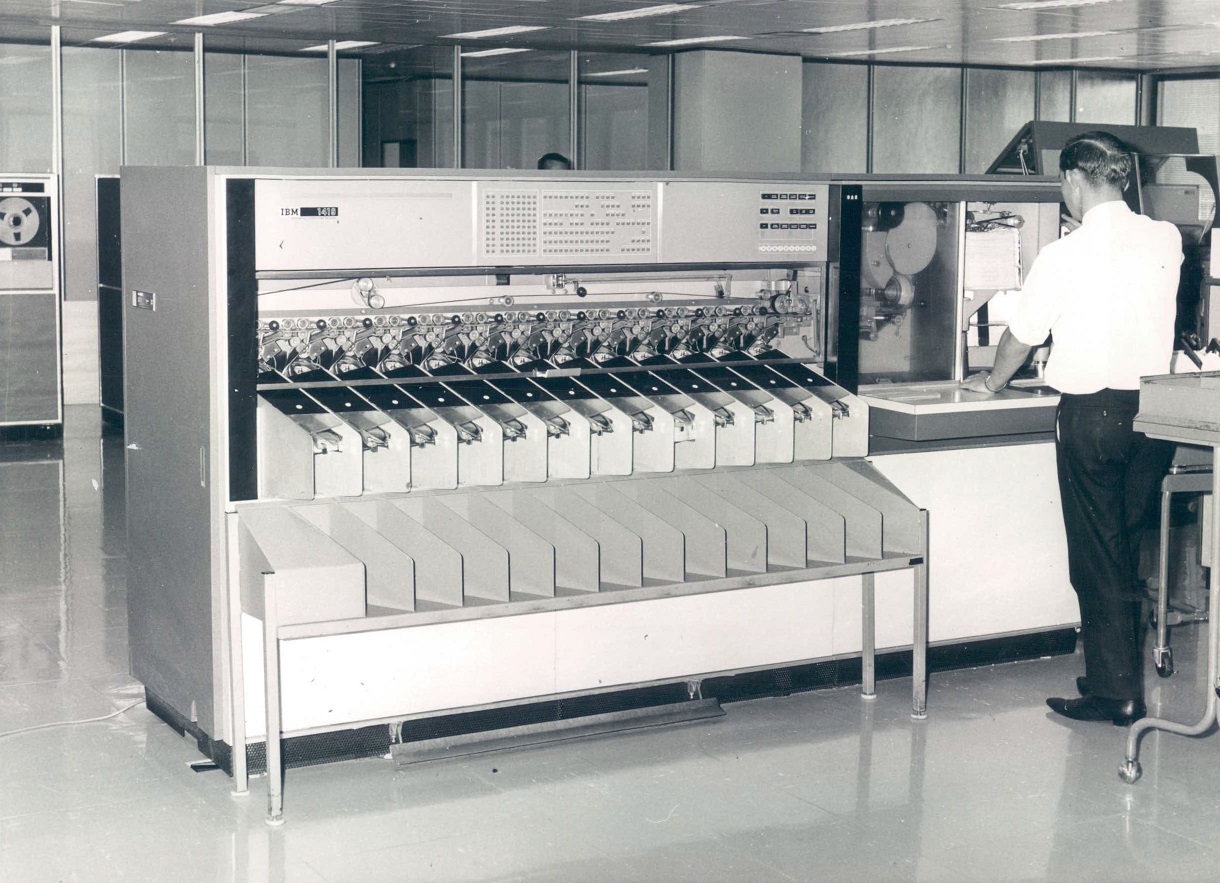

As well as meeting the demands of a modern office building, the Reserve Bank building was constructed with several specialised facilities. Because of the Bank’s need to maintain stores of gold, the building’s basement was equipped with special strongrooms. The strongrooms were the largest and most technically advanced in the southern hemisphere at the time of their installation. The doors of the strongrooms weighed 18 tons, and its walls were 75cm thick. A firing range was situated on the 18th floor for the training of the Bank’s security guards. The building incorporated a well-stocked library and a sizeable computing room to support the work of the Bank’s economists and researchers. A document lift and pneumatic tube system were also distinctive features.

[media]Although the building introduced a new architectural style to Martin Place, it alluded to aspects of the precinct’s commercial structures through its polished stone cladding and spacious two storey foyer. The building was also stylistically consistent with a new suite of Reserve Bank buildings constructed in each state and territory capital, which were designed and constructed by the same architects with the exception of the Canberra branch.

International Style

[media]The building’s architectural character relates to the International Style. Derived partly from the philosophy of the Bauhaus, the German school of architecture and the arts, the style advocated clarity, functionality and the simplification of architectural form, without reference to historical styles. Bauhaus teaching also reinforced the interrelationship between all the plastic arts within the overarching art of architecture. These principles informed the aesthetic of a number of Sydney’s buildings, especially those designed by Harry Seidler. Indeed, Martin Place showcases the final, significant sculpture of Bauhaus educator, Josef Albers, whose Wrestling (1977) was commissioned by Seidler as part of the environment of his MLC Centre, together with a foyer tapestry designed by Albers.

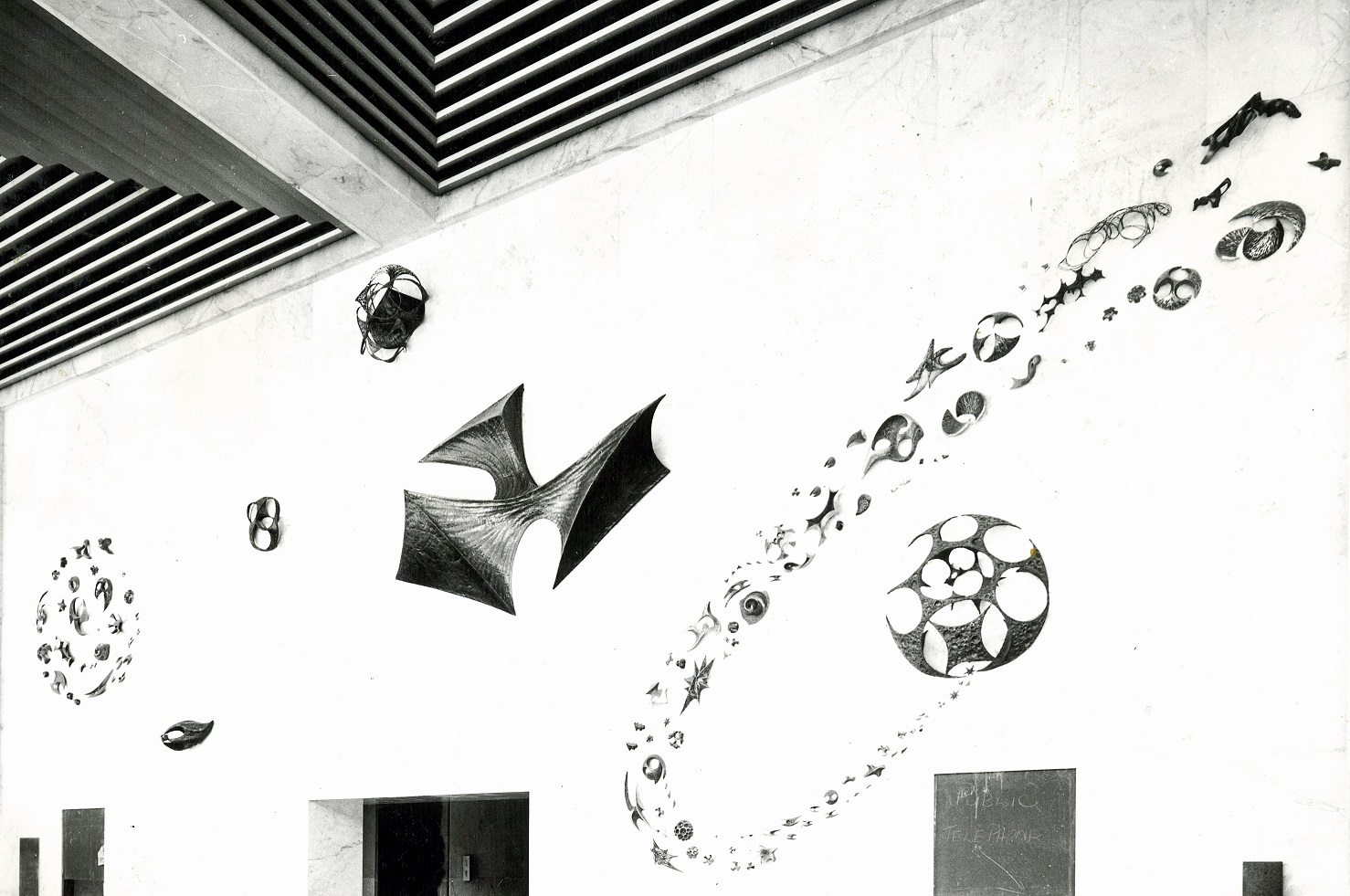

[media]In a similar way, the Bank commissioned works of art in diverse forms, including a tapestry by Margo Lewers for its boardroom. Competitions were held for a free-standing sculpture outside the building and a relief sculpture for the Bank’s foyer. Margel Hinder was awarded first place for her abstract sculpture that now stands adjacent to the Bank’s façade, and Bim Hilder’s wall enrichment was chosen for the foyer. Hilder’s sculpture integrates the design of the Bank’s new corporate emblem by Gordon Andrews, and shows it in a number of variations, reflecting the Bank’s influence in different spheres. Hilder’s work integrates architecture with sculpture and design in a way that realises the Bauhaus ambition to interrelate the plastic arts.

[media]Frederick Ward, one of Australia’s leading modernist designers, designed furniture for the building and oversaw its interior design. In the mid-1950s, Ward had criticised the state of Australian furniture design and advised that patronage by major agencies such as government departments may help to remedy the industry’s ‘unintelligent copying for uncritical patrons, both of past styles and present fashions’.[8] Dr Coombs was asked in 1958 to open a design conference, and he spoke of the ability of thoughtful design to contribute to the quality of everyday life, commenting that he preferred furniture which avoided imitation, pretension and superfluous decoration.

‘The capacity of simple everyday objects to express in some way the character of the people whom they serve is something which adds greatly to the richness of everyday experience...When commodities produced here have something to say to the world, not merely about their own purpose but about the qualities of Australian people and Australian life, the world will still want to buy them. They will pay for them and this will help the balance of payments.'[9]

[media]With the opportunity presented by the new head office, Coombs answered directly Ward’s criticism of government patronage. Coombs’ own office was decorated with thoughtfully selected Australian paintings and sculpture and functional modernist furniture. In 1968, Vogue’s Guide to Living featured Dr Coombs’ office alongside the executive suites created by Dior Perfumes, Fiat and Revlon.[10] These offices coupled the requirements of a working office with elegant settings of sofas and chairs for informal conversations, together with large oil paintings and works of sculpture.

Fred Ward also determined the arrangement of paintings by artists such as Charles Blackman, William Dobell, Russell Drysdale, Leonard French, Margo Lewers, Sidney Nolan, Carl Plate, Clifton Pugh, Lloyd Rees, and Fred Williams, that were acquired over time to complement its interior design, and to assist in promoting Australian art.

[media]In 1961, a competition was held seeking designs for a landscaped garden to serve as the building’s interface with Macquarie Street. Malcolm Munro’s garden plan was chosen for its geometric pattern of changing textures through gravel, pools of water and plantings comprised exclusively of native species, like the selection of the building’s Australian materials.

[media]At the time that the Reserve Bank’s headquarters were designed in the early 1960s, the Australian economy was increasingly opening itself to international influences. The design of the building in the International Style embodied the confidence of the country’s participation in the international economy, and conveyed an image of a modern, optimistic nation, as expressed decisively in Planned for Progress, the film commissioned by the Reserve Bank to document its construction.[11]

Notes

[1] John Murphy, Planned for Progress, Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia, 2010, 10

[2] John Murphy, Planned for Progress, Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia, 2010, 10

[3] Dr H.C. Coombs, speech and press statement for the opening of the Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, 10 December 1964, Reserve Bank of Australia Archives. Dr Coombs prepared a ‘mock speech’ and press statement for the building’s opening, but no official function marked the occasion.

[4] Reserve Bank of Australia Sydney promotional brochure, Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia, 1964, unpaginated

[5] Reserve Bank of Australia Sydney promotional brochure, Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia, 1964, unpaginated

[6] Reserve Bank of Australia Sydney promotional brochure, Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia, 1964, unpaginated

[7] Russell Rodrigo, ‘Banking on Modernism: Dr H.C. (Nugget) Coombs and the Institutional Architecture of the Reserve Bank of Australia’, Fabrications: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 26, no.1 (2016), 90 https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2015.1129687

[8] Frederick Ward, ‘The Problems of Furniture Design’, paper delivered at the Sixth Australian Architectural Convention, Adelaide, 1956, published in Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Philip Goad, Modernism & Australia, Documents on Art, Design and Architecture 1917–1967, Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2006, 819

[9] Dr H.C. Coombs, opening speech for the symposium, ‘Design in Australian Industry’, University of New South Wales, 1958, published in Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Philip Goad, Modernism & Australia, Documents on Art, Design and Architecture 1917–1967, Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2006, 835.

[10]‘The new look of executive offices …’ Vogue’s Guide to Living; Spring 1968, Sydney: Conde Nast Publications (Australia),1968

[11] Planned for Progress, Produced by David Koffel Film Productions, 1965, Reserve Bank of Australia Archives AV0000373/1