The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Muslims in Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Muslims in Sydney

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Sydney-siders learned some unlovely truths about the intolerance of their fellow citizens for minorities. There were the 'race riots' at Cronulla Beach in December 2005, after text messages incited 'Aussies' to take revenge against 'Lebs and wogs'. [1] In early 2008, at Camden, local non-Muslims demonstrated violently against proposals by other locals to build a new Muslim school in the area. [2] Such incidents might lead one to believe that Muslims are a recent – and, for some people, unwelcome – addition to the city's demographic mix. However, Muslims have long been part of Australia's history, and of Sydney.

Early Muslims in Australia

Some of Australia's earliest visitors – well before European settlement – were Muslims from the east Indonesian archipelago. They were fishermen from Macassar, who came to fish for 'trepang', commonly known as the sea slug and considered a delicacy by the Chinese. [3]

According to Bilal Cleland, author of The Muslims in Australia, other early colonial records indicate a Muslim presence. The 1792-96 Norfolk Island Victualling Book mentions that in January 1796 the island received several Muslim sailors, and at least eight convicts who arrived in Australia after 1813 were of 'Arab or part-Arab' heritage. Cleland states

Evidence was given before an Immigration Committee in 1838 that over 100 settlers had organised for 1203 Indian [including Muslim] labourers to be brought in, and between 1837 and 1844 about 500 did arrive. [4]

Another group of Muslims who played an important role in nineteenth century Australia, in the centre and far north, were the 'Afghans', who were camel drivers from the Indian sub-continent. They played a vital role in the early exploration of the north of the continent and, from 1870 to 1872, the establishment of the overland telegraph line between Adelaide and Darwin, which eventually linked Australia to London via India. [5] The Ghan – the train between Adelaide and Darwin – was named in recognition of the work of these Afghan cameleers.

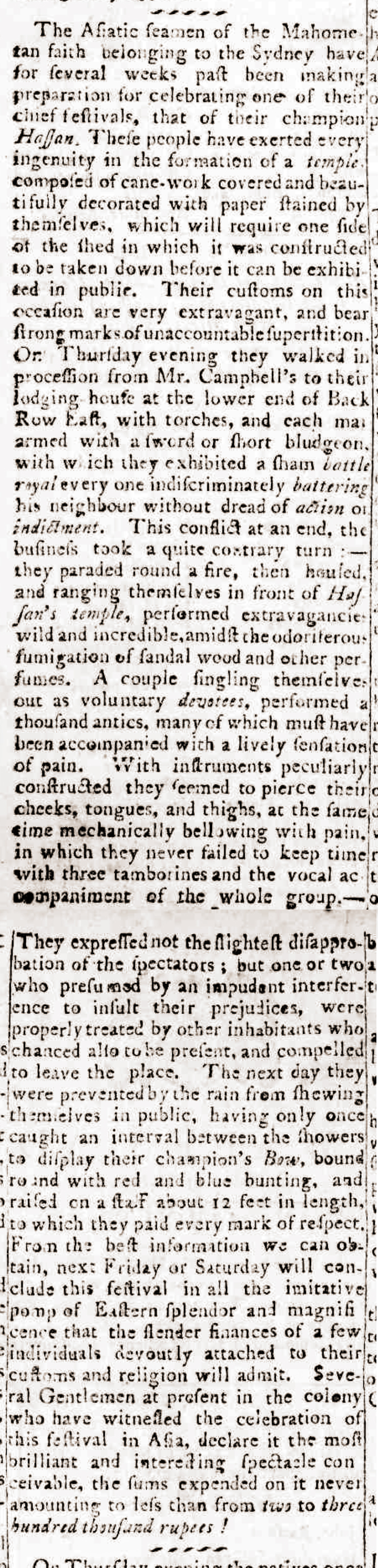

Muslims in Sydney

Sydney [media]has also had a long involvement with Muslim people. In 1795 John Hassan, one of several Muslim crewmen on the colonial-built ship Endeavour, left Port Jackson, only to see his ship scuttled off New Zealand. [6] In the 1870s, 'Afghan' traders set up their place of worship in Haymarket. However, from the 1850s Anglo-Celtic colonists grew increasingly concerned about 'the Asian hordes' to the north and developed severely racist attitudes, culminating in a formal 'White Australia' policy that was implemented by the newly formed Commonwealth Government from 1901 as the Immigration Restriction Act.

Australian Muslims under the White Australia Policy

[media]The impact of the Immigration Restriction Act was soon felt. When Sayyid Mahomet Shah Banuri applied to the Secretary for the Department for External Affairs for a Certificate of Domicile in 1903 he submitted a petition of support signed by a variety of Sydney's Indian and Syrian Muslims and Christian merchants, most of whom appear to have lived in Redfern. [7] Shah Banuri was apparently a well-educated religious leader who spoke Arabic, Persian, Pashtu, Hindustani and Sindhi and intended to visit India and the Hejaz to further his religious education, but feared he would have difficulties re-entering the country to return to his flock in Sydney. He was eventually granted a twelve month Certificate of Exemption in November 1903. [8] Such cases highlight the difficulty faced by Muslims living in Australia under the White Australia Policy.

By 1921 there were fewer than 3,000 Muslims living in all Australia, and very few in Sydney. [9] Indeed, between 1901 and 1921 the number of 'Afghans' fell from 393 to 147. [10] (The term 'Afghan' was applied somewhat indiscriminately to people of various ethnicities from the Pakistan/northern India area.) A Sufi Muslim group came to Sydney and settled, ironically in the context of recent events, in the Camden area. [11] However, as Australian National University sociologist Shakira Hussein notes, the group came under the auspices of a German national, Baron Frederick Elliot von Frankenberg, as a form of indentured labour, and so were not subject to the usual unsympathetic bureaucratic scrutiny. [12] Another group of Muslims that managed to enter Australia in the 1920s were from Albania, but as they were Europeans, they were accepted as 'white'. [13]

'White Australia' policies restricted immigration to Europeans until the election of the Whitlam government in 1972.

Muslim migration after the White Australia Policy

Perhaps surprisingly, the first intakes of Muslims were refugees from the Middle East. Following civil war in Lebanon in the 1970's, Lebanese Muslim migration increased dramatically. [14] While Sydney had long been home to Lebanese communities, many of these were Maronite Christians, who had arrived in the 1880s, and settled in the Redfern and Zetland area, the closing decades of the twentieth century saw dramatic growth in the city's total Muslim population, which increased by 90 per cent between 1981 and 1991, with the largest ethnic groups being Lebanese and Turks. The 1991 Census revealed that 50 per cent of Australian Muslims lived in Sydney, and another 32 per cent lived in Melbourne. [15]

As with many new immigrant groups, umbrella support groups were soon formed. The Islamic Council of NSW (ICNSW) was established in 1976. It was open to all Muslims (regardless of race, colour and ethnicity) and to any Muslim organisations in New South Wales. Its primary aims are to advocate for, support, and develop Muslim communities, and to foster and promote cooperation between Muslims and others. In the same year, the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils was formed, and while initially based in Melbourne, it shifted to Zetland, near Redfern in Sydney, the location of an early Muslim community in that city. [16]

Modern Muslim communities in Sydney

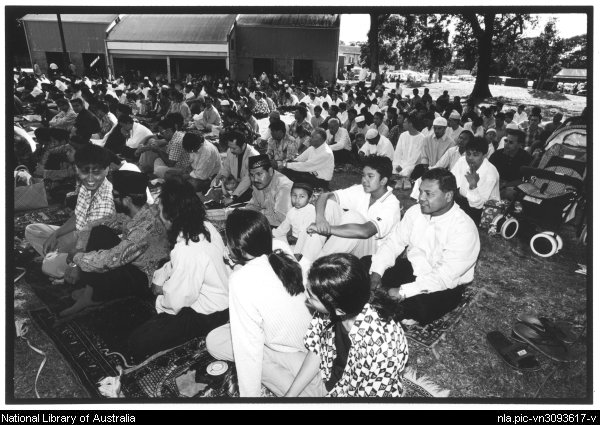

[media]Mosques and community organizations played, and continue to play, a critical role in the life of Muslims in Sydney. Today, there are more than 120 mosques spread across the city, although they cluster most strongly in areas where there is a large Muslim population, as in Sydney's west and south-west, around Bankstown, Auburn and Liverpool. As The Sydney Morning Herald has noted, many of these mosques and musallas (prayer halls) have an ethnic flavour. Sydney's Turkish Muslim community tends to congregate at the Gallipoli Mosque in Auburn and the mosque in Bonnyrigg, while the lives of Lebanese-Australian Muslims centre on the Ali Ben Abi Talib Mosque in Lakemba and a series of other mosques and prayer halls in Belmore and Bankstown. Hundreds of Bosnian Muslim families who escaped the civil war in their homeland in the early 1990s have found a refuge at the Smithfield Mosque, in Smithfield. [media]More ethnic variety is seen at the Zetland Mosque, where people of dozens of different ethnic and social backgrounds share prayer mats, while in the Ryde Musalla, services are given in Urdu and English, to cater for both the local Pakistani community and other ethnic groups. [17]

Prejudice against Muslim community activities in Sydney

Community support is important in a society that has long been xenophobic about 'foreigners'. Although long-held expectations that migrants should 'assimilate' and abandon their culture and traditions in favour of 'traditional Australian values' have been replaced by ideas of multiculturalism, prejudice comes in many forms. One Camden resident told The Sydney Morning Herald in 2008 that he felt burying Muslims in the St Thomas Anglican Cemetery, which dated back to 1839, might compromise its heritage value. He said 'I've got nothing against migrants but when they want to take over your cemetery…' [18]

Nor are community leaders immune from expressing racist attitudes. In February 2006, during a debate over the availability of the abortion pill mifepristone (RU486), Danna Vale, the Liberal MP for the federal NSW seat of Hughes, stated the number of abortions being carried out each year would eventually lead to Australia becoming 'predominately Muslim'. [19] Her inflammatory and ill-informed comments revived the 'populate or perish' slogan of the years of the White Australia policy.

[media]The 2008 proposal to build an Islamic school in Camden brought out similar attitudes. Yet Islamic schools aren't exactly a new idea in Sydney. The Malek Fahd Islamic school, for example, was established in 1989 in Greenacre near Bankstown, with just 87 children. [media]It now has 1,700 students. Camden has a high proportion of religious schools, with eight Catholic schools and three other-denominational Christian schools serving the needs of nominally Christian members of the community.

The tensions in Camden are not the only examples of attempts to prevent Muslims from exercising their rights as citizens. Over the last two decades, Muslims in metropolitan Sydney, where roughly half the Australian Muslim population lives, have been surprised to find, despite Australian rhetoric about freedom of religion, it is the norm for local governments to deny permission to establish mosques and schools. In 1981, in Campbelltown, the local Islamic society sought Council permission to establish an Islamic Centre. They were hindered by opposition from local residents and the local newspaper, which portrayed the centre as a potential fortified building, bristling with armed guards. The centre went ahead, but only after ten years of disputation. Camden Council and the Fairfield Council have also been involved in lengthy disputes with the Muslim community over the rights of Muslims to establish Islamic centres. [20]

Another prominent case occurred in Sefton in 1995, when the Bangladesh Islamic Centre of NSW bought a disused Presbyterian church in Helen Street. As the church had been zoned as a place of worship since 1954 the Society was sure it would be a suitable site for a mosque. But Bankstown Council thought otherwise – it permitted use of the existing church as a place of public worship for only 12 months then withdrew permission. A challenge went to the Land and Environment Court of NSW, where Justice Terry Sheahan ruled that 'A mosque, while a place of worship, is not a church, which is a place of worship in the Christian tradition', and awarded costs against the Bangladesh Society. [21] This decision was not only widely publicized within Australia, but throughout the Muslim world, and highlighted the way that prejudice can subvert a legal system. It also caused much public outrage in Sydney, expressed by the Premier, Bob Carr, Ali Roude, the chairman of the Islamic Council of NSW, and Stepan Kerkyasharian, chairman of the state's Ethnic Affairs Commission. The Islamic Society lodged an appeal, and in March 2000 the three judges of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of NSW set aside the ruling that a 'church' could not be a mosque. [22] This hard-fought outcome went some way to reassuring the Muslim community's belief in the potential of Australia's multicultural society, although the Gulf Wars of 1991 and 2003 saw increasing levels of violence against Muslims in Sydney. [23]

Offensive behaviour is not entirely one-sided. In 2006 the ever-controversial Sheik Taj Aldin al-Hilali, Australia's most senior Islamic cleric, responded to news of the sexual assault of four young Sydney women by a group of young Lebanese men by saying women who didn't dress 'appropriately' and would 'sway suggestively' as they walked, wearing make-up and 'immodest dress' were 'uncovered meat.' He was quoted as saying

If you take out uncovered meat and place it outside...without cover, and the cats come to eat it...whose fault is it, the cats' or the uncovered meat's? The uncovered meat is the problem. [24]

There was broad community outrage about his words, shared by Muslim community leaders, who condemned Sheik Hilali for his comments and insisted that he no longer deserved his title as Australia's mufti. [25]

Muslims in twenty-first century Sydney

[media]Today, Muslims comprise only 1.9 per cent of all Australians but approximately 3.4% of Sydney's population is Muslim. This comprises about half of Australia's Islamic population. [26]

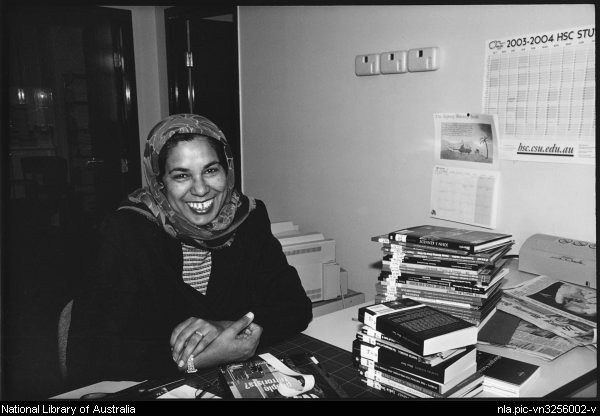

Muslims in Sydney are ethnically, linguistically and culturally diverse, having come from more than 120 countries. The 2001 Census shows New South Wales has the largest Muslim population, with nearly a third of the city's Muslims born here, while other major sources were Lebanon (ten percent), and Turkey (eight percent). Other countries from which Muslims have migrated to Sydney include Afghanistan, Bosnia, Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh and Iran. The Muslim presence is now part of Sydney's diverse culture. They are particularly concentrated in the suburb of Lakemba and surrounding areas such as Punchbowl, Wiley Park, Bankstown and Auburn. [27]

The [media]annual Eid Festival and Fair draws large crowds of Muslims and non-Muslims alike, while support groups have sprung up, not only in suburbs where there is a large Muslim population, but also in universities and schools. The Islamic Society of Sydney Boys High School represents the Muslim community of that school, and provides a prayer room for the daily prayers as well as a newsletter and regular Da'wah (call to Islam) activities, while in nearby Randwick, Kensington and Kingsford, many restaurants serving foods from a variety of Muslim cuisines have appeared. [28]

[media]In any multicultural society, there will always be debate about identity, and the advent of increasing numbers of Muslims in the city has prompted Sydney-siders to consider, once again, issues of cultural identity, challenging, as they do, a mind-set of generally Anglo-centric values, values which have in the past not been representative of Australia's multicultural diversity.

In the second decade of the 21st century things seem to be changing for the worse again. Early in 2014 the Liberal-National Government, led by Tony Abbott, declared it would amend the Racial Discrimination Act by repealing section 18C, which makes it unlawful for someone to publicly 'offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate' a person or a group of people. The Attorney General, George Brandis, told his fellow senators

People do have a right to be bigots you know…In a free country people do have rights to say things that other people find offensive or insulting or bigoted. [29]

Although this seemed like an act flagging a return to the old days of a less civil and civilized world, it now appears unlikely to pass a hostile Senate.

At the end of 2014, another incident occurred which allowed anti-Muslim sentiment to surface – the tragic siege at the Lindt Café in Sydney's Martin Place. A deranged gunman, out on bail and with a history of domestic violence, held customers hostage while making numerous demands. He was eventually shot dead by police, but his request for an Islamic State flag led many to believe that he was part of some terrorist plot. While a few commentators tried to make that link, strong leadership from prominent public figures ensured that such sentiments were treated with the contempt they deserved. [30]

References

Bilal Cleland. The Muslims in Australia: A Brief History. Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002; also at http://islam.iinet.net.au/channel/islam_australia.html

Abdullah Saeed. Islam in Australia. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2003

MuslimVillage Incorporated. MuslimVillage Inc, 2001-2012. http://muslimvillage.com/

'The Face of Islam'. The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 August 2007. http://www.smh.com.au/specials/islam/

Notes

[1] 'Mob violence envelops Cronulla, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 December 2005, http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/mob-violence-envelops-cronulla/2005/12/11/1134235936223.html, viewed 4 February 2014; SBS, Cronulla Riots: the day that shocked a nation, SBS, http://www.sbs.com.au/cronullariots/, viewed 6 July 2013.

[2] Angela Cuming and Caroline Marcus, 'A town's dirty secret', The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 2007, http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2007/11/10/1194329563801.html, viewed 6 July 2013

[3] Bilal Cleland, The Muslims in Australia: a Brief History (Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002), 8-10

[4] Bilal Cleland, The Muslims in Australia: a Brief History (Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002), 13-17

[5] Bilal Cleland, The Muslims in Australia: a Brief History (Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002), 19-24; Wafia Omar and Kirsty Allen, The Muslims in Australia, (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1996), 9

[6] White Christian Civilisation to the East, The Islamic Council of Perth Western Australia, 2015, http://www.islamiccouncilwa.com.au/white-christian-civilisation-to-the-east/, viewed 16 April 2014.

[7] Muslims and the Police of Racial Exclusion from 1901, The Islamic Council of Perth Western Australia, 2015, http://www.islamiccouncilwa.com.au/muslims-and-the-policy-of-racial-exclusion-from-1901/, viewed 16 April 2014

[8] Muslims and the Police of Racial Exclusion from 1901, The Islamic Council of Perth Western Australia, 2015, http://www.islamiccouncilwa.com.au/muslims-and-the-policy-of-racial-exclusion-from-1901/, viewed 16 April 2014

[9] Islam in Australia, IslamCan.com, http://www.islamcan.com/islamic-history/islam-in-australia.shtml, viewed 16 April 2014

[10] Jens Sorensen Lyng, Non-Britishers in Australia (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1935), 187

[11] The Argus, Melbourne, Saturday 19 February 1938, 10

[12] James Jupp, 'Religion and Integration in a Multi-faith Society', in Multiculturalism and Integration: A Harmonious Relationship, edited by Michael Clyne and James Jupp, (Canberra: ANU ePress, 2011), http://press.anu.edu.au?p=113381, 137

[13] James Jupp, 'Religion and Integration in a Multi-faith Society', in Multiculturalism and Integration: A Harmonious Relationship, edited by Michael Clyne and James Jupp, (Canberra: ANU ePress, 2011), http://press.anu.edu.au?p=113381, 137

[14] Bilal Cleland, The Muslims in Australia: a Brief History (Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002), 75-76

[15] Special Feature: Trends in religious affiliation, 4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, 1994, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 27 May 1994, http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/2f762f95845417aeca25706c00834efa/10072ec3ffc4f7b4ca2570ec00787c40!OpenDocument, viewed 4 February 2014

[16] Islamic Council of New South Wales website, http://www.icnsw.org.au/, viewed 4 February 2015; Australian Federation of Islamic Councils, Muslims Australia, http://muslimsaustralia.com.au/contact-us/, viewed 4 February 2015

[17] Details of the various ethnic groups and the mosques where they practice their faith can be found in Husnia Underabi, Mosques of Sydney and New South Wales Research Report (Auburn: Charles Sturt University Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation, Islamic Sciences and Research Academy Australia, University of Western Sydney School of Social Sciences and Psychology, 2014), http://uws.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/754140/IS0001_ISRA_NSW_Msq_Rprt.pdf, viewed 4 February 2015

[18] Linda Morris, 'Over Camden's Dead Body', The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 September 2008, http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/over-camdens-dead-body/2008/09/24/1222217331341.html, viewed 16 April 2014

[19] Stephanie Peatling, 'Abortion will lead to Muslim nation', The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June 2006, http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/abortion-will-lead-to-muslim-nation-mp/2006/02/13/1139679540920.html, viewed 16 April 2014

[20] Tom Iggulden, 'Camden Council rejects building Islamic School, ABC Lateline, 27 May 2008, http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2007/s2257133.htm, viewed 2 February 2015

[21] 'Q: Why is this church not a church?', The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 October 1998

[22] 'After the Second World War,' Islamic Council of Perth Western Australia, 2015, http://www.islamiccouncilwa.com.au/after-the-second-world-war/, viewed 16 April 2014

[23] 'After the Second World War,' Islamic Council of Perth Western Australia, 2015, http://www.islamiccouncilwa.com.au/after-the-second-world-war/, viewed 16 April 2014

[24] Mark Tran, 'Australian Muslim leader compares uncovered women to exposed meat', The Guardian, 26 October 2006, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/oct/26/australia.marktran, viewed 12 July 2013. The men at least did receive long gaol sentences.

[25] Mark Tran, 'Australian Muslim leader compares uncovered women to exposed meat', The Guardian, 26 October 2006, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/oct/26/australia.marktran, viewed 12 July 2013

[26] Drew Warne-Smith, 'Muslim numbers to rise 80pc in 20 years', The Australian, 29 January 2011, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/muslim-numbers-to-rise-80pc-in-20-years/story-e6frg6nf-1225996403047, viewed 16 April 2014

[27] Islam in Australia, Islamic Population Worldwide, http://www.islamicpopulation.com/Oceania/Australia/Islam%20in%20Australia.htm, viewed 16 April 2014

[28] Sydney Boys High Facebook page, incorporating Islamic Society of Sydney Boys High School, https://www.facebook.com/SydneyBoysHigh?rf=110213342332643, viewed 4 February 2015

[29] Emma Griffiths, 'George Brandis defends 'right to be a bigot' amid Government plan to amend Racial Discrimination Act', ABC News, 24 March 2014, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-03-24/brandis-defends-right-to-be-a-bigot/5341552, viewed 8 April 2014

[30] 'Sydney Siege: TV hostage interviews won't affect inquest', SBS News, 29 January 2015, http://www.sbs.com.au/news/storystream/sydney-siege-tv-hostage-interviews-wont-affect-inquest, viewed 2 February 2015