The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Marrickville

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Marrickville

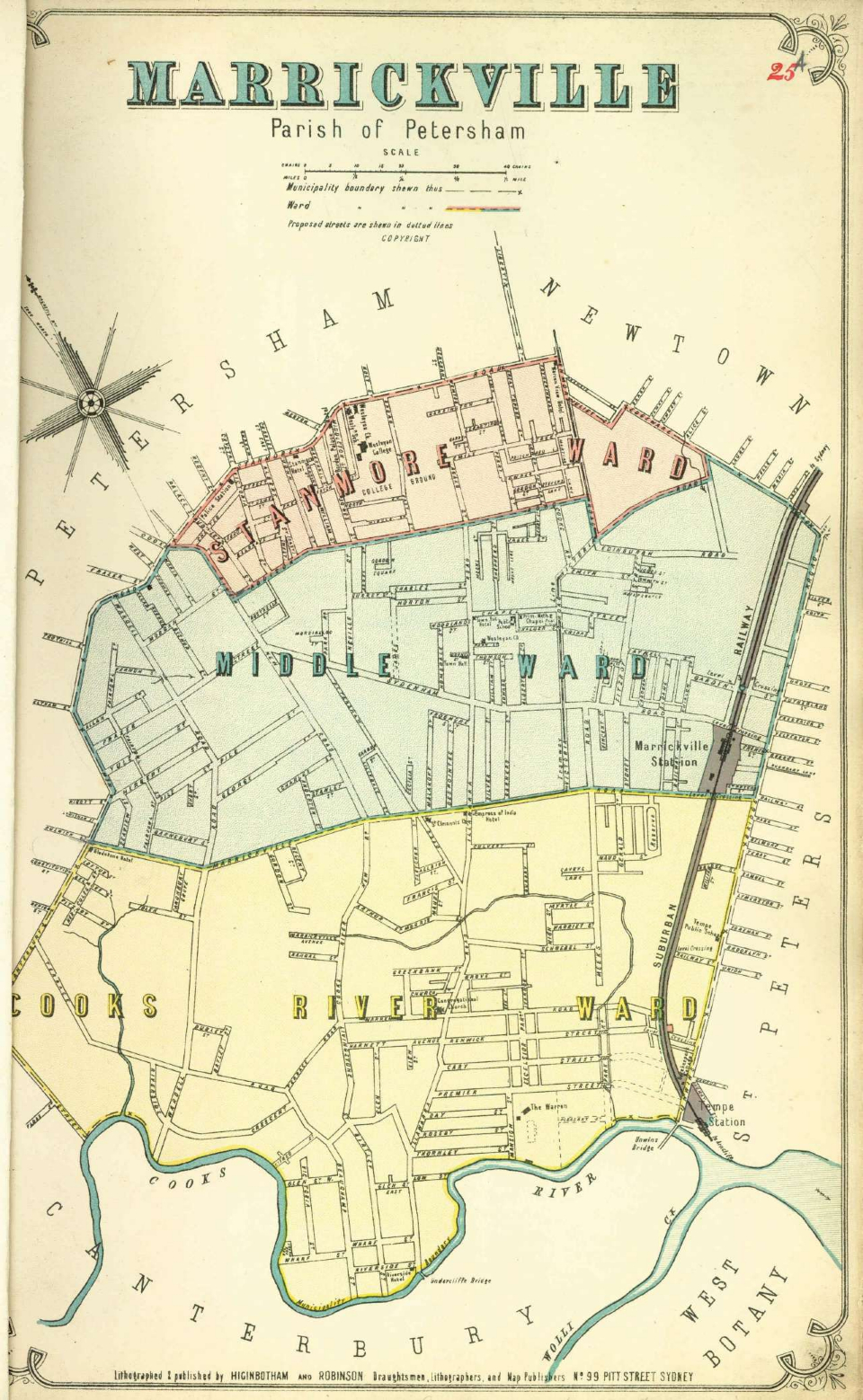

Marrickville [media]is the largest suburb in the Marrickville local government area, six kilometres southwest of Sydney. Most of the suburb of Marrickville consists of a valley – a natural low-lying saucer – that is part of the Cooks River basin. Marrickville railway station is a just 7.6 metres above sea level. The traditional owners of the land are Cadigal of the Eora Nation. The Aboriginal name for the area is Bulanaming.

Gumbramorra swamp

Following European settlement, Marrickville was a place where runaway convicts could easily hide out in the bush or disappear quietly into the Gumbramorra swamp, which was a natural boundary between Marrickville and what now comprises the suburbs of St Peters, Sydenham and Tempe. The swamp was almost always impassable.

The role of the swamp wetlands played an important part in Aboriginal life as a source of plants and animals. It supported a dense growth of thatch reed, providing an excellent habitat for a variety of birds, particularly swamp hens, moorhens, ducks, gulls and the occasional pelican.

After European settlement its role in the ecological system was not fully understood or appreciated, and the swamp was drained in the 1890s to facilitate the industrialisation of the suburb.

Timber!

In the first decades after European settlement Marrickville was simply regarded as a good source of timber for boatbuilding. Thomas Moore harvested the timber, which was sufficiently valuable for him to issue several notices in the Sydney Gazette in 1803 warning that 'trespassers intent on cutting timber would be prosecuted to the utmost rigour of the law'.

The status of the area changed with the arrival of the flamboyant Dr Robert Wardell, a wealthy barrister, who purchased more than 2,000 acres (800 hectares), including the former estate of Thomas Moore.

When Wardell arrived there were still valuable stands of timber on the estate. Wardell employed his own timber-cutters, selling it mainly for firewood. Like Moore he had trouble with people sneaking onto his property and lopping down the trees and, similarly, he routinely thundered in the press about prosecuting those responsible. The Sydney Gazette of 29 May 1830 noted that Wardell's timber had been

valued at the extraordinary sum of 40,000 pounds. The property comprises two or three thousand acres, and is, in some places, very thickly wooded. Incredible as the estimate may appear, we are inclined, from the increasing scarcity and dearness of firewood to think it was not much above the mark.

The life and death of Dr Wardell

Wardell lived the [media]high life, entertaining prominent citizens of Sydney at his home, Sara Dell, located on Parramatta Road in Petersham – now the site of Fort Street High School. Wardell conducted hunting parties through the bush to Cooks River and, in an effort to recreate conditions of 'home', fenced his entire property and stocked it with imported English deer under the watchful eye of a gamekeeper.

Wardell had arrived in Sydney in 1824 with William Charles Wentworth. Together they established a weekly newspaper, The Australian , which was the first independent newspaper in the colony. Wardell had a brilliant mind. He was also pugnacious in promoting popular causes, repeatedly clashing with Governor Darling. He once fought a duel with Darling's brother-in-law.

Wardell was murdered by runaway convicts as he rode out on a Sunday morning, 7 September 1834. Two men, John Jenkins and Thomas Tattersdale, were arrested, tried and convicted. On 7 November 1834 they were hanged for their crime. The third person involved, Emmanuel Brace, a boy of 16, gave evidence against his former companions and escaped the death penalty.

Wardell [media]was buried in the Sydney burial ground, now the site of Central railway station, but his remains were later removed and returned to England for burial in the family vault. In 1839 a marble tablet, showing a portrait modelled from his death mask, was installed in St James Church, Sydney.

Wardell's violent death came at a time when there was much concern about convict lawlessness. It caused a huge outcry and calls for increased penalties and police to protect the citizenry of Sydney. Since Wardell's brutal murder there have been several conspiracy theories about who really wanted him dead.

Agriculture and industry – Marrickville is established

The demise of Wardell opened the way for the first great era of subdivision in Marrickville. His estate, administered by Wentworth, was divided among his sisters, Anne Fisher, Margaret Fraser and Jane Isabella Priddle. The estate, which Wardell had protected so jealously from trespassers, was now unlocked.

Market gardeners found the area attractive because of its good water supply. From Scotland came the Meek, Graham, Purdy and Moncur families. They were joined by Chinese market gardeners such as Sun Hop Yin and Mow Chow. Other new arrivals included Italians, such as Nicholas Compagnoni.

Stonemasons with an eye for good sandstone also headed for the rocky outcrops of Marrickville. Adam Schwebel, a German migrant, arrived to quarry the sandstone cliffs along Cooks River and the ridge lines of the Marrickville valley. These early settlers formed the foundations on which multicultural Marrickville was built.

The year 1855 was a turning point in Marrickville's development. Thomas Chalder subdivided his Marrick Estate and laid down the village of Marrickville. Cottages, shops, churches and civic buildings rapidly appeared. Market gardens, dairy farms and stone quarries now dotted the landscape. Parts of Marrickville remained well timbered and were still referred to as Wardell's Bush.

Marrickville was a diverse area. Along with the market gardeners, stonemasons and dairy farmers, it was also home to architects, lawyers, members of parliament and senior public servants. The first mayor of the Marrickville Municipality, incorporated in 1861, was Irish-born Gerald Halligan, the chief clerk in the New South Wales Public Works Department.

In 1878 the first Marrickville Town Hall was built on Illawarra Road. It is the oldest civic building in Marrickville and the fourth oldest surviving town hall building in Sydney. It was sold to the State Government in 1920 to fund the building of the new town hall on Marrickville Road.

[media]By the late 1860s Marrickville was described as a rural suburb with pretty scenery and handsome residences. There were many dairy farms catering for the growing local population as well as serving Sydney and adjacent suburbs. One of the earliest and largest dairies was Norwood Park, owned by John Neville. Although parts of it were progressively sold, the dairy operated into the early years of the twentieth century. The remaining portion was bought by the federal government in 1914 and developed as an army depot. It is now the site of Addison Road Community Centre

The Warren

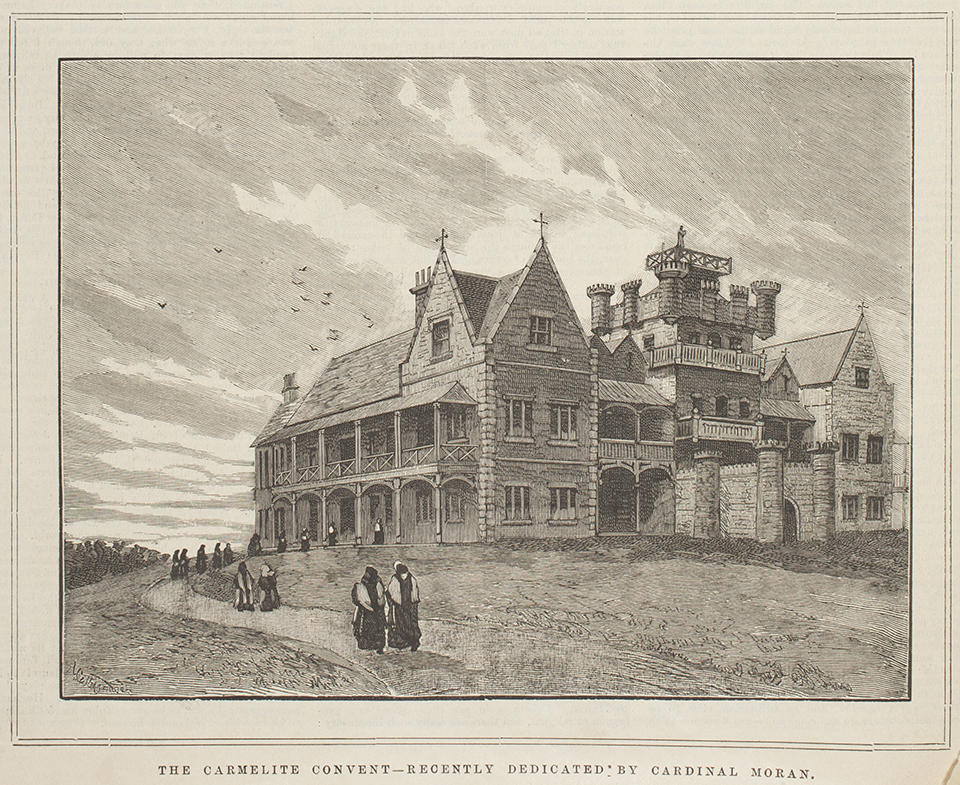

Marrickville's [media]population may have increased and diversified but the suburb was not done with its millionaire residents. In 1864 Thomas Holt, wool merchant and politician, built The Warren, a castellated Victorian Gothic mansion complete with its own art gallery, on his 130-acre (53-hectare) estate overlooking Cooks River. Holt also built bathing sheds and a Turkish bath on Cooks River for his personal use.

Holt was an enterprising individual. He was a member of the colonial parliament and a founding member of the AMP Society, the Sydney Railway Company, the Australian Joint Stock Bank and (Royal) Prince Alfred Hospital. One of his favourite causes was an adequate supply of water for Sydney, which was essential for future development.

[media]After Holt returned to England in 1883 his estate was subdivided. The Warren and 12 acres (five hectares) of land were purchased by a French order of Carmelite nuns. The Carmelites were evicted from The Warren in 1903 for outstanding debts. Eventually they were able to establish a new monastery in Wardell Road, Dulwich Hill.

[media]The Warren was used as an artillery training camp during World War I. The property was resumed in 1919 by the New South Wales government and the house demolished. Sir John Sulman was engaged to build a housing estate for returned soldiers.

The Warren may be long gone, but it still exerts a powerful fascination. Residents, both old and new, often refer to their locality as The Warren. Its presence can be sensed in many ways. Two towers from The Warren stand on Richardson's Lookout in Holts Crescent. Ferncourt Public School is built from the stone of The Warren's demolished stables. On the banks of Cooks River, hidden behind concrete, are the remains of The Warren's burial vaults, where, for a little while, the Mother Superior of the Carmelite order rested in peace. A large amount of sandstone from The Warren, acquired by Marrickville Council, was recycled into retaining walls and kerbs and gutters throughout the suburb.

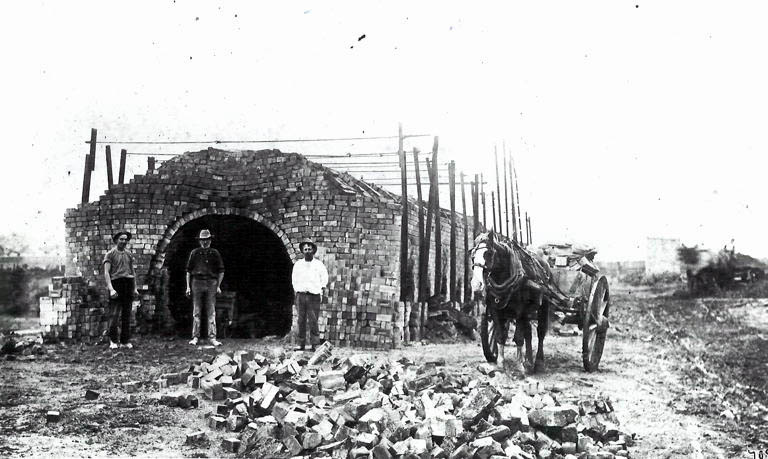

Brickmaking takes over

As Thomas Holt sailed back to England, Marrickville was still an area mostly taken up with market gardens and small-scale brickmaking. By the late 1880s many of the market gardens were converted into the more profitable brick pits, sometimes by the same family. The loamy clay soil once used to grow vegetables to feed the population was now converted to bricks to house it. At first the bricks were made by hand, but with the introduction of steam-made and then machine-made bricks, Marrickville took on a semi-industrial character. It became home to the largest brickmaking businesses in Sydney. In 1888 Johnston Brothers was producing up to 300,000 bricks per week.

Brickmaking had a lasting impact on the physical and social environment of Marrickville. Grand homes were demolished to make way for more and more brick pits, while the large estates were rapidly subdivided to provide cheap housing for the population needed to work in the brick pits or large potteries, such as Fowler's. Marrickville was now the suburb of the working family.

As [media]the clay diminished, so did the brickworks. In the end the empty, desolate pits were left to fill with water and became dangerous places where young people took a gamble on a hot summer's day for the reward of a cool swim. Drowning tragedies occurred in almost every waterhole. Marrickville Council resumed the old brick pits for public parks in the 1920s and 1930s. Most parks in Marrickville, most notably Henson Park, are built over former brick pits.

The rise and fall of industry

From the 1890s large numbers of industrial companies were established in Marrickville including woollen mills, steel and metal operations and automotive and various service industries. With the rise of heavy industry the population surged ahead of neighbouring suburbs.

The first and largest woollen mill in Marrickville was Vicars, a family-run business established in 1893. Vicars advertised their goods as 'Made in Australia by Australians for Australians from Australia's pure wool only'. By the 1960s Vicars was suffering serious competition from other fabrics, and in the early 1970s the federal government substantially reduced tariffs on imports. Vicars Woollen Mills could no longer compete and the company was wound up. The Marrickville Metro shopping centre opened in 1987 on the site. Part of the factory wall was retained and the Vicars name is still proudly seen on the facade. The Mill House, built about 1860 and occupied by the Vicars family, was incorporated in the redevelopment. It is one of the oldest buildings in Marrickville.

The period between World War I and World War II saw tremendous industrial growth in Marrickville. Industry provided almost universal employment for local men and women. In the mills of Vicars, Globe and the Australian Woollen Mills, women constituted over 70 per cent of the workforce, mostly involved in spinning, weaving, combing and mending. Men did the dirtier and heavier, but better paying, jobs of sorting raw wool, dyeing and moving bales.

Whole families spent their working lives in the confines of one factory within walking distance or a short bus or tram ride from their homes. Marrickville was proud of its industry, holding regular industrial exhibitions of its home grown products.

By 1935 there were more than 130 manufacturing businesses in Marrickville. The mayor, Henry Morton, boasted in a poem that everything you wanted was manufactured in Marrickville. The goods he described ranged from chocolates to fishing lines and guitars through to saucepans and shoes, radios and rugs to heavy-duty machinery and mowers, margarine, bathtubs and boots. It was an interesting chronicle of ordinary household goods plus essential items for the building and manufacturing industries.

When the minister for labour and industry, JJ Maloney, opened the Marrickville Centenary Fair in 1961 he described Marrickville as an important industrial municipality with some 900 different industries and undertakings.

Among the exhibitors at the fair was the Omega Trading Company, which made one of Marrickville's more peculiar claims to fame – Australia's first insecticide and deodorant blocks. They were an instant success.

The process of deindustrialisation began in the 1970s. Many of the larger concerns, such as the woollen mills and Fowler's Potteries, either closed or decentralised, moving their operations to cheaper land and larger premises on the suburban fringe.

With the disappearance of the large factories the lure of plentiful factory work was gone. The Australian Woollen Mill was demolished to build a school. The Globe Woollen Mill was converted into home units. The site of the Vicars Woollen Mill became the Marrickville Metro. There are still industrial zones within Marrickville but they are mainly populated by light industries employing smaller number of workers.

Entertainment

Life in Marrickville was not all about slogging away on the factory floor. The building of the new Marrickville Town Hall in 1922 on Marrickville Road gave the suburb a first-class venue for dancing and other entertainments.

Dances were organised three times a week by the 'Strollers', Bert Gibb and his son Hector. The dances were so popular that the local tramways inspector often had to put on additional trams to take patrons to the railway station at Sydenham or into Sydney.

[media]Marrickville Town Hall also echoed to the strains of the Marrickville Municipal Symphony Orchestra under the musical directorship of Fred Hanney, a music teacher and a member of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. The Marrickville Municipal Symphony Orchestra was established in 1930 and was the first council-supported suburban orchestra in Sydney.

In the sombre days of World War II, concerts by the Municipal Symphony Orchestra and the Strollers' dances provided much needed diversions. Many of the concerts raised funds to send medical aid to Russia under the auspices of the Lord Mayor's Patriotic Fund. The chairwoman of the fund's Russian Medical Aid and Comforts Committee was Jessie Street, a well known socialist, socialite and founder of the United Associations of Women.

Multicultural Marrickville

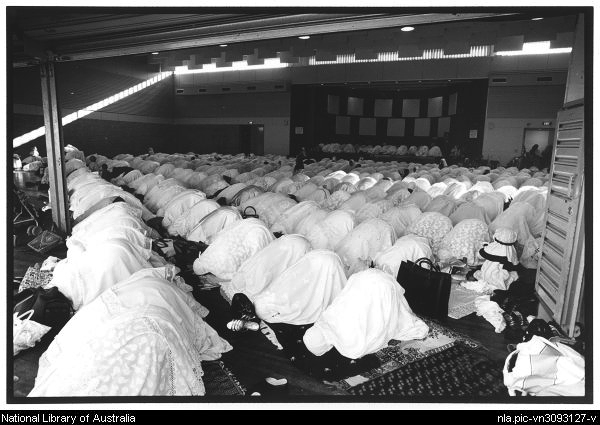

After World War II, Marrickville was transformed into one of the most diverse societies in Australia. The influx of mainly non-English speaking people, attracted by the availability of factory work and cheap housing, changed Marrickville over a very short period.

Greek-born migrants formed the largest postwar community in Marrickville. The Greek newspaper To Neo (March 1986) evoked the times, describing how

wherever you turned, you heard Greek, wherever you looked you saw Greek shop signs.

The main shopping strip of Marrickville Road was dominated by Greek shopkeepers. Taking up business was not always without problems for the new migrants. Giannis (Jack) Cordatos, one of Marrickville's most prominent Greek migrants, had to resort to subterfuge to purchase the Classic Milk Bar. The owners did not want to sell to southern Europeans but were impressed by French speakers. Cordatos changed his name to Revel and won the sale. Marrickville became known throughout Sydney as 'the Athens of the west'. There remains a strong Greek presence in Marrickville.

Vietnamese and Chinese migrants arrived in the 1980s and began to establish themselves as shopkeepers and restaurant owners along Illawarra Road.

[media]Marrickville has a long tradition of receiving migrants and a new migrant is likely to be living beside an older migrant, who went through the same process a generation earlier. The establishment of Addison Road Community Centre in 1976 provided a venue for many multicultural groups to join with their communities and mix with others. The shared experiences of migrants in Marrickville generally built a tolerant and accommodating society.

There were spectacular 'rags to riches' stories. Vojtech Zimmer, born in Vienna, fled Austria at the beginning of World War II. He joined the free Czech forces but was torpedoed off Gibraltar. He then joined French forces in the south of France. At the evacuation of Dunkirk he became a British soldier. Zimmer arrived in Sydney in 1948 and took various factory jobs before establishing a company to sell Hungarian spices and condiments. The factory moved to Marrickville in the 1960s. Zimmer was affectionately known as the Paprika King, receiving in 1973 an Order of the British Empire.

The Indigenous population

[media]There is a significant Indigenous population in the Marrickville area. At the 2006 census 1,078 people identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, 1.5 per cent of the total population of the Marrickville local government area, compared with 1.1 per cent in the Sydney Statistical District. Reports from workers in community organisations indicate that these people were under-represented in the 2001 census and this was probably the case again in 2006. The number of Indigenous residents continues to grow.

The Inner West Aboriginal Community Cooperative was incorporated in 1999. It is located in the former Marrickville Hospital, Lilydale Street, Marrickville. Since 1985, whenever it is the turn of the Aboriginal city sides to host the annual NSW Aboriginal rugby league knockout carnival, it has been held at Henson Park. In 1996 Marrickville Council formally recognised a Statement of Commitment to Aboriginal people.

Marrickville today

Marrickville's close proximity to Sydney makes it an attractive option for inner city living. Its streets are a mixture of architectural styles, with older terrace housing standing quite comfortably next to Federation bungalows. New unit developments are springing up on former factory sites. Previous service station sites are also giving way to unit and townhouse development. Marrickville is living up to its long established reputation as an area that embraces change. The population is changing too, with new settlers coming from the Pacific Islands, Africa and South America.

Marrickville celebrates its cultural diversity with fervour. Every September the colourful Marrickville Festival arrives and the community generally parties throughout the day to the beat of a variety of multicultural dance groups and musicians.

References

Marrickville Chamber of Commerce, 'Advance Marrickville: Grand Shopping Carnival April 21st to May 3rd, 1913', Marrickville Chamber of Commerce, Marrickville NSW, 1913

JG Henderson, 'Official souvenir, Marrickville Municipality: diamond jubilee, opening of new Town Hall and industrial exhibition', Marrickville Municipal Council, Marrickville NSW, 1922

Guardian and Newtown Daily, 'Centenary Supplement', 1961

Marrickville Municipal Council, 'A History of the Municipality of Marrickville to commemorate the seventy-fifth anniversary, 1861–1936', Harbour Newspaper and Publishing Co, Sydney, 1936

'Jubilee Souvenir of Marrickville', compiled by Marrickville Municipal Council, Marrickville NSW, 1912

'List of Manufacturers, 1947', compiled by Marrickville Municipal Council, 1947

'List of Manufacturers, 1965', compiled by Marrickville Municipal Council, 1965

'Marrickville Manufacturers Exhibition, 1935, March 28th to April 6th', compiled by Marrickville Municipal Council, 1935

Richard Cashman and Chrys Meader, Marrickville: Rural Outpost to Inner City, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1990

Chrys Meader, Richard Cashman and Anne Carolan, Marrickville: People and Places, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1994