The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Echo Point

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Echo Point

Echo Point, [media]high above the Jamison Valley on the southern edge of Katoomba, is the most popular scenic lookout in the Blue Mountains. Its viewing platforms offer panoramic views of the orange cliff tops of the Kings Tableland to the east, Mount Solitary opposite and the long plateau of Narrow Neck to the west. Viewed from a height of almost a kilometer above sea level, the undulant blue-green contours of the valley floor resemble a sea or gentle labyrinth; the huge valley often filling with spectacular formations of mist and cloud. However, Echo Point is most famous for the iconic Three Sisters rock formation, to the immediate east of the viewing platforms. These three craggy sandstone rock-towers, emerging from an eroded cliff, provide a picturesque focal point, making this an especially popular location for taking photographs.

[media]Situated in Gundungurra and Darug country, and emerging as a major tourist destination in the 1920s, Echo Point now attracts around 1.4 million visitors a year. Because of its popularity (almost 'loved to death' in the words of one newspaper) [1] it is an uncanny site which for almost a century has combined a 'holiday playground' [2] atmosphere with the sublime. This constant tension between the beautiful and kitsch makes it a compelling site for thinking about the many different ways of seeing that have shaped the Blue Mountains landscape: Indigenous, Romantic, commercial and environmental.

[media]Originally named Tri Saxa ('three stones') Point by its colonial viewers – its Aboriginal name was not recorded – Echo Point did not particularly lure early scenic tourists. Between 1879 and 1925 it was part of an industrial landscape with mines for shale and coal operating between Narrow Neck and Mount Solitary. Huge flying foxes and cliffside cable tramways transported ore and workers – who also had encampments in the valley – to the town above. [media]While the Blue Mountains train line opened in 1876, the same year Katoomba (previously known as 'The Crushers') was officially named, the point remained part of Sir Frederick Darley's 'Lilianfels' estate until 1908, meaning that visitors had to negotiate private access. Those in search of views or a sublime subject to sketch or photograph tended to favour the Weatherboard (later Wentworth) Falls, Govetts Leap (near the village of Blackheath) or even the Burragorang Valley, later flooded to form Sydney's Warragamba Dam.

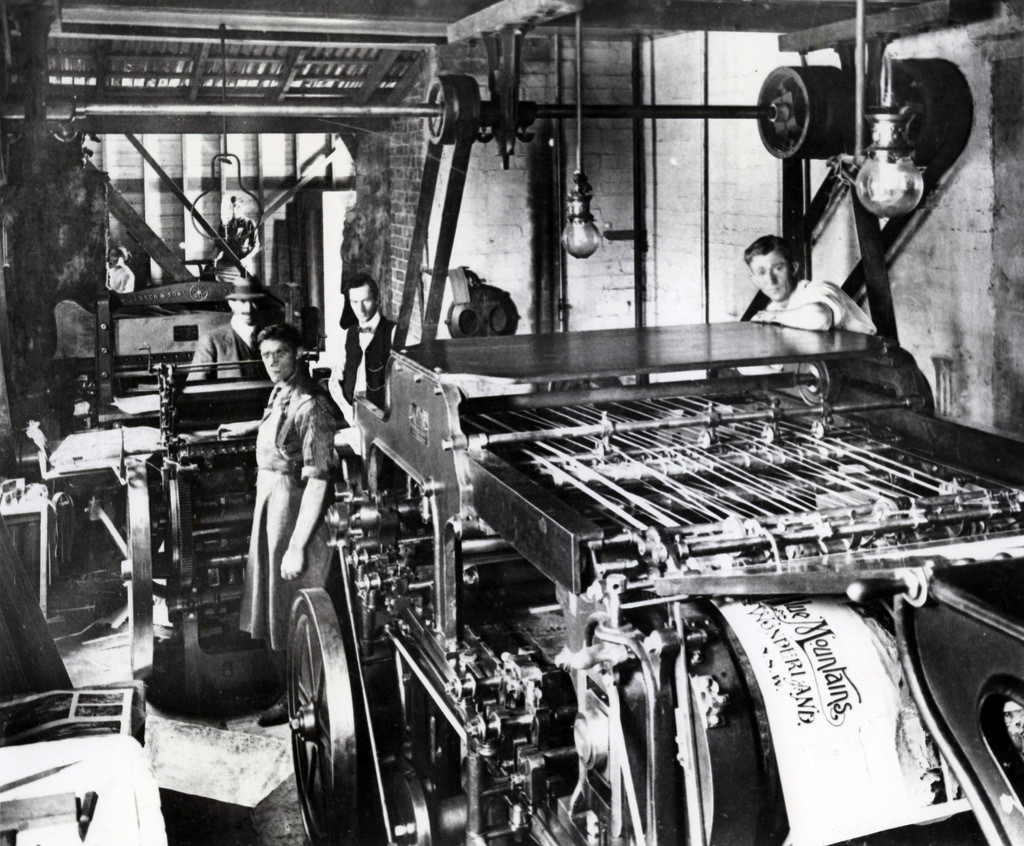

[media]Nevertheless, there was sufficient interest in the area's attractions for it to be renamed in 1890 as 'Echo Point', while the three stone pillars became the 'Three Sisters'. In this way it was part of a common story, as an imported European romanticism embodying the 'grand dreams of elsewhere' [3] transformed sites in the mountains into 'sights'. (Nearby lookouts were named Tarpeian Rock and Sublime Point, while the natural rock formation on Mount Solitary became known as the 'Ruined Castle'). Tourists were very much part of this process, describing dawn, dusk and weather from the area's various lookouts in deathless prose, which they sent to publications such as the Blue Mountains Echo.

The Three Sisters

[media]Although the Three Sisters are now central to the iconography of Echo Point, it was Orphan Rock, the isolated and lopsided sandstone pinnacle to the immediate west of the lookout, which most excited Victorian tourists. Invested with sentimental notions of independence and pluck, the outcrop was a ubiquitous image on commemorative spoons and crockery, also serving as the icon for the chocolates sold by Katoomba's famous Paragon Cafe and Dash's Department store in Leura Mall ('The Orphan Rock and Dash's stand alone'). The three pillars, on the other hand, with their eerily sheer orange facades, seemed to puzzle tourists, perhaps because they were harder to reconcile with European notions of the picturesque. Contemporary writers compared them to 'a cathedral with weird spires' and 'weird monuments of Egyptian architecture.' [4]

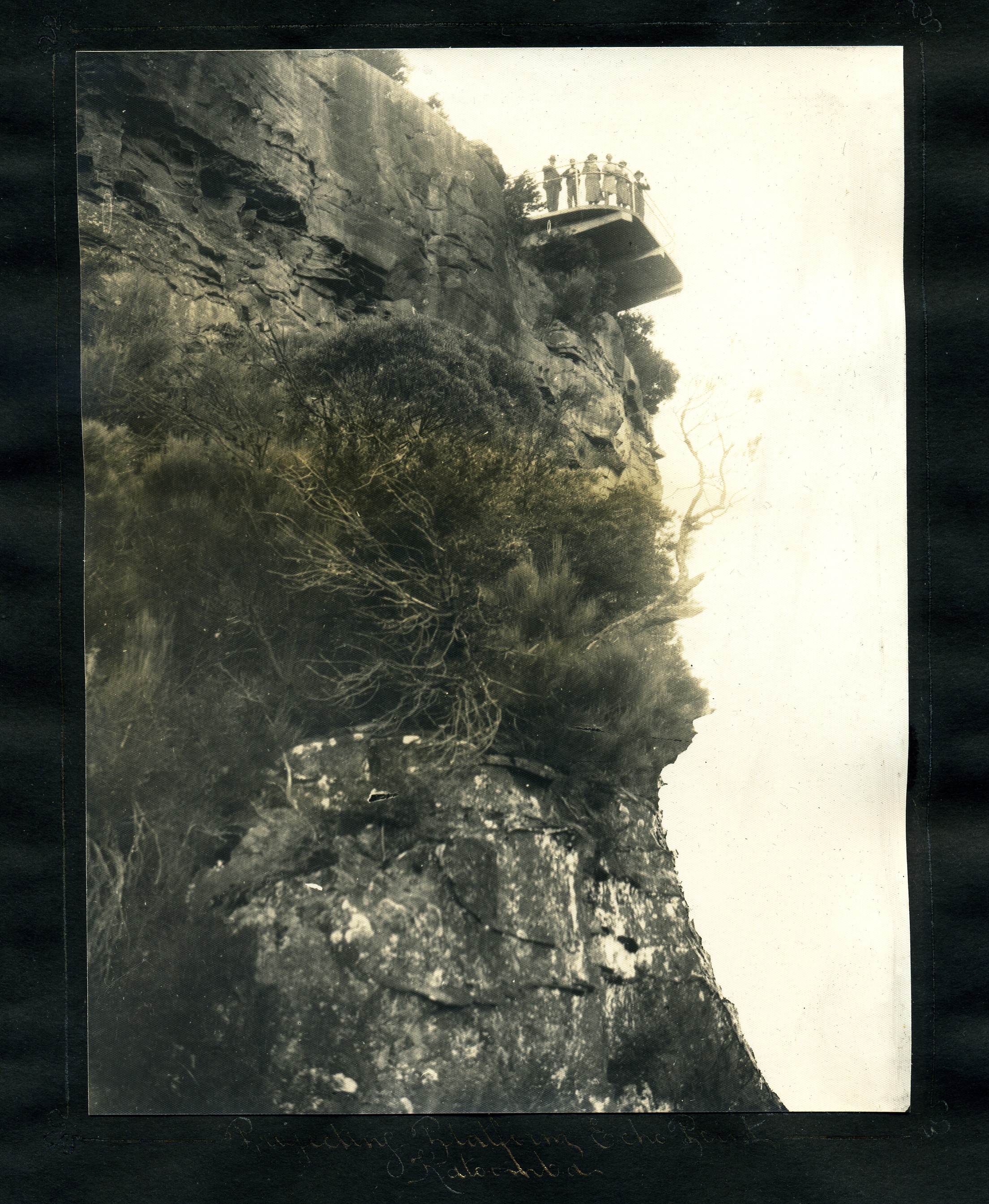

[media]It was only around the turn of the century, as Katoomba boomed as a tourist destination, that the Three Sisters became the dominant sight that they remain today. In 1912, The Katoomba Municipal Council placed the Three Sisters on the cover of its official tourist guide while photographers like Frank Hurley created iconic images of the valley. [media]The projecting platform (later Queen Elizabeth Lookout) and the Giant Stairway, with its decorative stone arch creating a gateway to the valley, opened on the same day in 1932.

[media]Photographer Harry Phillips arguably did more than anyone to make Echo Point famous. [5] From 1908 into the 1920s Phillips sold souvenir view books from his Katoomba Street shop. Filled with panoramic photographs that exaggerated the curvature and length of the area's cliffs and steps, and featuring looming skyscapes, the postcards were so well-known they were sent to soldiers in the trenches in the World War I. A cloud fanatic, romantic and relentless booster of the mountains, Phillips specialised in images of clouds and mist rising from the Jamison Valley, often shot from a perspective above the darkly jutting curve of Echo Point. He also popularized the somewhat kitsch conceit of three women posed in front of the Three Sisters. [6]

The 'Indigenous' legend of the Three Sisters did not attach itself to the public story of Echo Point until 1949, when Melbourne (Mel) Ward, proprietor of the Pyala Museum – an ethnological and natural history museum that relocated in 1959 from the Hydro Majestic Hotel in Medlow Bath to Echo Point's La Plaza building – published it, claiming to have learned it from Indigenous informants in Burragorang. In Ward's version, the 'sorcerer' of the Katoomba tribe turned the three beautiful sisters Weemala, Meenie and Gunedoo into stone in order to save them from being carried away by young men of the Nepean tribe. Dying in the subsequent battle, he was unable to change them back, so that they remain petrified on the valley's edge.

Historians have expressed great skepticism about this legend which has become central to the charisma of Echo Point. Yet recent work between the traditional landholders and local authorities suggests the 'Three Sisters' name and legend may have grown around the grain of local knowledge. In 2005, Bill Hardie, then chairman of the Gundungurra Tribal Council, said that the Gundungurra identify the Three Sisters as the remnants of an original seven stone pagodas and that they are an intimate part of the Muggadah, or 'Seven Sisters Dreaming', linked to the Seven Sisters of the Pleiades star cluster. According to the late Darug elder, Aunty Joan Cooper, women would give birth in a cave near Echo Point and the men would watch the third sister –who would bow her head – for a sign that the birth had occurred. [7] The NSW government declared the Three Sisters an Aboriginal Place in 2014.

Tourism and development

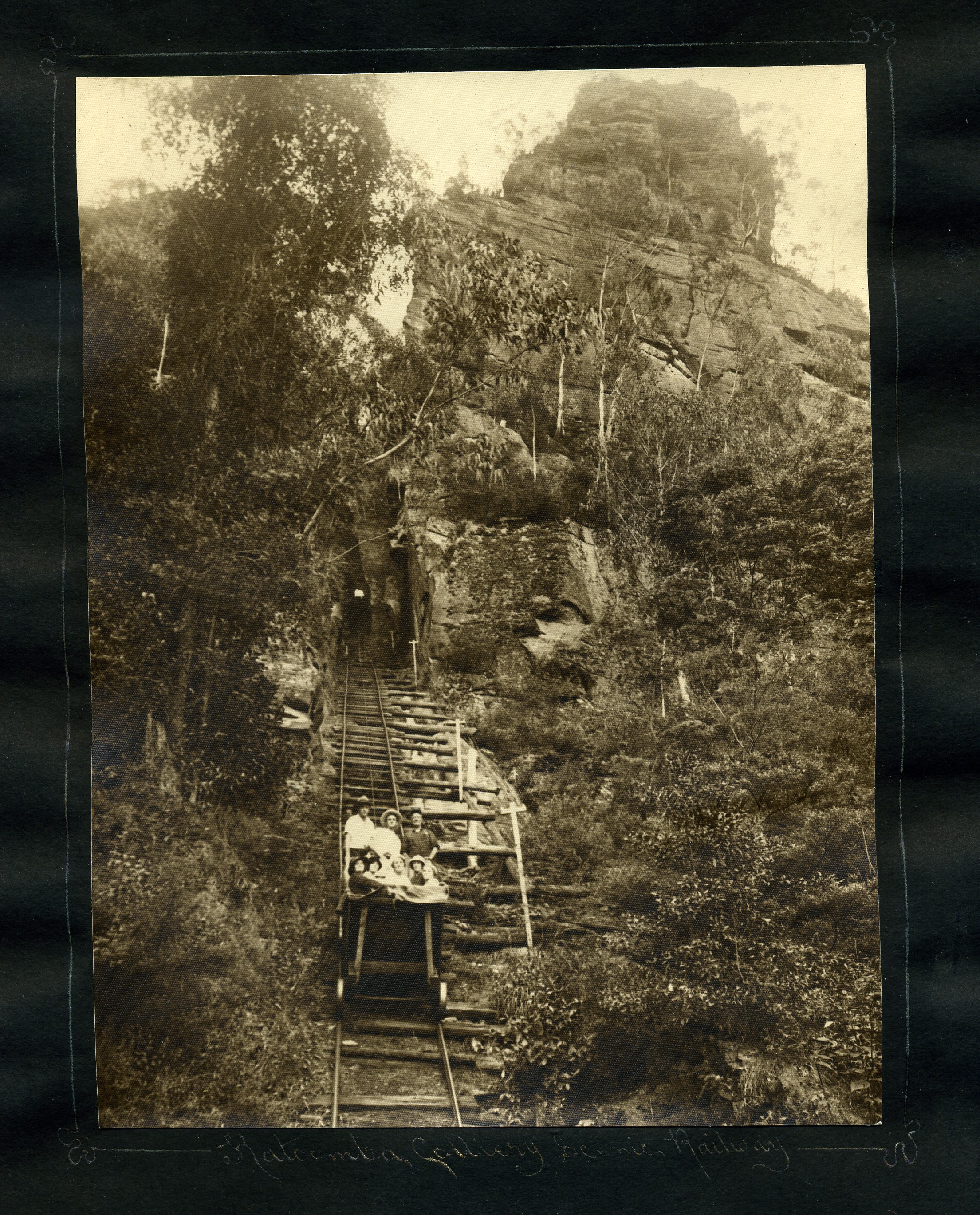

Echo Point's [media]popularity has also made the area a site of intense commercial activity. Since 1945 the Hammon family's Scenic World complex has drawn tourists to the valley's western edge. Refurbished extensively in 2013, it offers tourists thrill rides on its near-perpendicular Scenic Railway (originally the Katoomba Colliery's coal hoist), glass-floored Scenic Skyway (also made originally from salvaged mine equipment) and more sedate Scenic Cableway. (The Orphan Rocker, a derelict rollercoaster on the cliff's edge, is part of local mythology; constructed in 1983, but failing to meet safety standards, it has never carried a paying passenger). [media]From the 1930s to the 1950s, Dan Evans 'the Felixman' took souvenir photographs of tourists at the Echo Point lookout, posing them with child-sized Felix the Cat and Mountain Devil props, [8] while various buskers, including Indigenous didgeridoo player Goombar Wylo, have performed there.

[media]By the late nineties, concerns about appropriate development simmering as far back as the 1920s, [9] focused on the number of tourist coaches blocking the lookout with engines running, 'reminiscent of George Street – peak hour,' as one resident wrote to the local paper. [10] In 1998 the Blue Mountains City Council commissioned plans for a major redevelopment of the site with the aim of reducing traffic and making the area more pedestrian-friendly. In 2003, the refurbished Echo Point opened . Its vast new drum lookout six meters above the old projecting platform, offers a 270-degree view; new balustrade lighting, seating and interpretive signs aim to 'create a sense of anticipation’ and improve the 'climax experience'. [11]

It could be argued that the visual ecology of the Three Sisters and Jamison Valley, reproduced so often over so many decades, has become a cliché; certainly, it is perceived as the point-and-click alternative to more 'authentic' and immersive modes of entering the Greater Blue Mountains wilderness, which UNESCO granted World Heritage status in 2000.

Yet Echo Point's ambiguity and resistance to neatly scripted experience persist, most poignantly in its history as a popular suicide destination, and in the uncertainty that shrouds its Indigenous past. As historian Martin Thomas writes of the area's history, 'the more light you shine, the hazier it gets.' [12] Perhaps all the layers of human manipulation present at Echo Point enhance, rather than dispel, the site's mysterious power.

The question of whether there is, in fact, an echo at Echo Point also remains unsettled, the subject of humorous debate in newspaper letters pages throughout the last century. Some locals claim a 'cooee' from the suspended lookout will echo from the left of the Three Sisters while others have suggested it will return, with a long time delay, from the Kanimbla Valley beyond Narrow Neck; though, as local historian Jim Smith observed, 'two minutes is an awfully long time to the impatient tourist of today.' [13]

Further reading

Falconer, Delia. The Service of Clouds. Sydney: Picador, 1997.

Kay, Phillip. The Far-Famed Blue Mountains of Harry Phillips. Leura, NSW: Second Back Row Press, 1985.

Thomas, Martin. The Artificial Horizon: Imagining the Blue Mountains. Carlton, Victoria: University of Melbourne Press, 2003.

Notes

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 December, 1997, 7

[2] Frank Hurley, quoted by Martin Thomas, The Artificial Horizon: Imagining the Blue Mountains (Carlton, Victoria: University of Melbourne Press, 2003), 158

[3] Delia Falconer, The Service of Clouds (Sydney: Picador, 1997) 1

[4] John Low, Blue Mountains Pictorial Memories (Crows Nest, NSW: Atrand Pty. Ltd, 1991), 90

[5] Harry Phillips – whose life embodied so many of the contradictions in ways of seeing the mountains – is the fictionalised subject of my novel The Service of Clouds (Sydney: Picador, 1997). For more on this much-loved, eccentric Blue Mountains character, see Phillip Kay, The Far-Famed Blue Mountains of Harry Phillips (Leura, NSW: Second Back Row Press, 1985)

[6] However, Martin Thomas points out in that posing three women at the Three Sisters was a popular photographic conceit extending back to the 1890s: Martin Thomas, The Artificial Horizon: Imagining the Blue Mountains (Carlton, Victoria: University of Melbourne Press, 2003),159–161

[7] Daniel Lewis, 'Once were seven – now we must protect the last sisters', The Sydney Morning Herald, August 29, 2005, http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/once-were-seven--now-we-must-protect-the-last-sisters/2005/08/28/1125167552293.html, viewed 13 January 2016

[8] John Merriman, 'Mr Evans, the Felixman of Echo Point,' blogpost, Blue Mountains Local Studies, Wednesday June 25, 2008, http://bmlocalstudies.blogspot.com.au/2008/06/mr-evans-felixman-of-echo-point.html, viewed 13 January 2016

[9] Echo Point was perceived to be neglected in the 1920s. In 1988, the Blue Mountains City Council moved to demolish the Echo Point observation platform and shelter shed when big cracks appeared in the walls and floor of the shelter shed beneath. 'Echo Point is Falling Down', Blue Mountains Gazette, 20 December, 1988

[10] S McKay of Katoomba, letter to the editor, Blue Mountains Gazett, 3 June 1998

[11] On 30 September, 1998, the Blue Mountains Gazette reported that the plan's design philosophy for the area was to 'create a sense of anticipation by providing a gateway and small glimpsed of the view' and to 'allude to the attraction of a sandstone precipice and the Blue Mountains without belittling the experience.'

[12] Martin Thomas, The Artificial Horizon: Imagining the Blue Mountains (Carlton, Victoria: University of Melbourne Press, 2003),153

[13] See, John Cronshaw, letter to the editor, Blue Mountains Gazette, 9 December 1987 and Jim Smith, letter to the editor, Blue Mountains Gazette,16 December 1987

.