The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Darlinghurst Gaol

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Darlinghurst Gaol

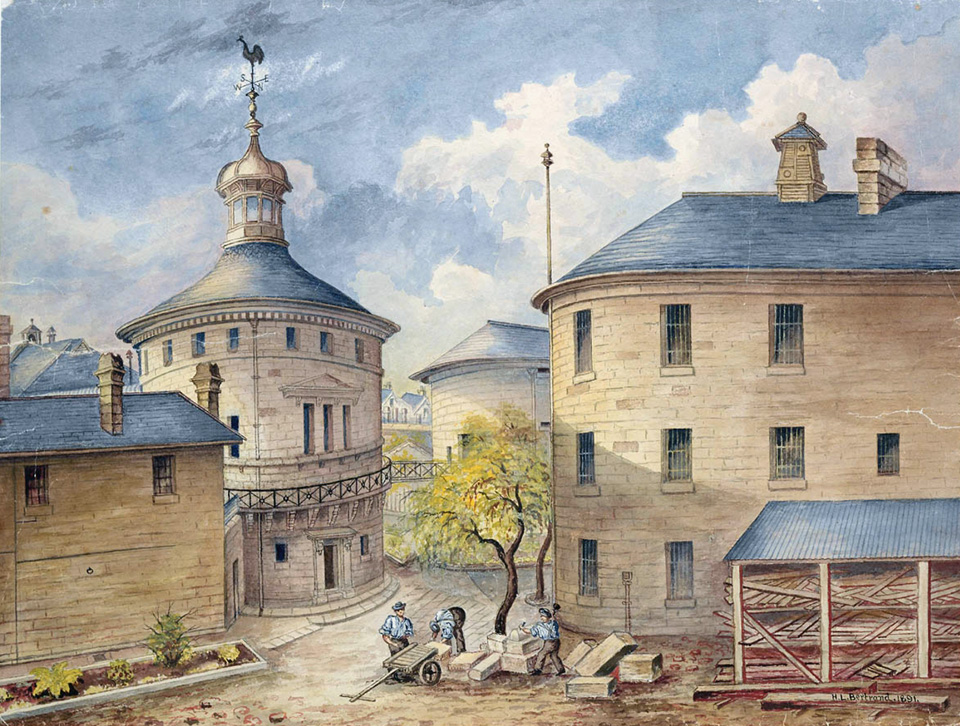

[media]In the early 1820s it was decided to build a gaol on Darlinghurst Hill, and Francis Greenway was commissioned to design a building that would overlook Sydney, as a constant reminder that Sydney was a convict town. The walls of the jail were built by convicts between 1822 and 1824. However, after an initial flurry of activity that saw the outer walls constructed, building languished for want of funds. [1] It was only the pressure of extreme overcrowding in the existing gaol in The Rocks that forced the colonial administration to act, and in 1835 a further £35,000 was voted by the legislature to complete the building. [2] Work recommenced in 1835 – but it took 50 years to finish.

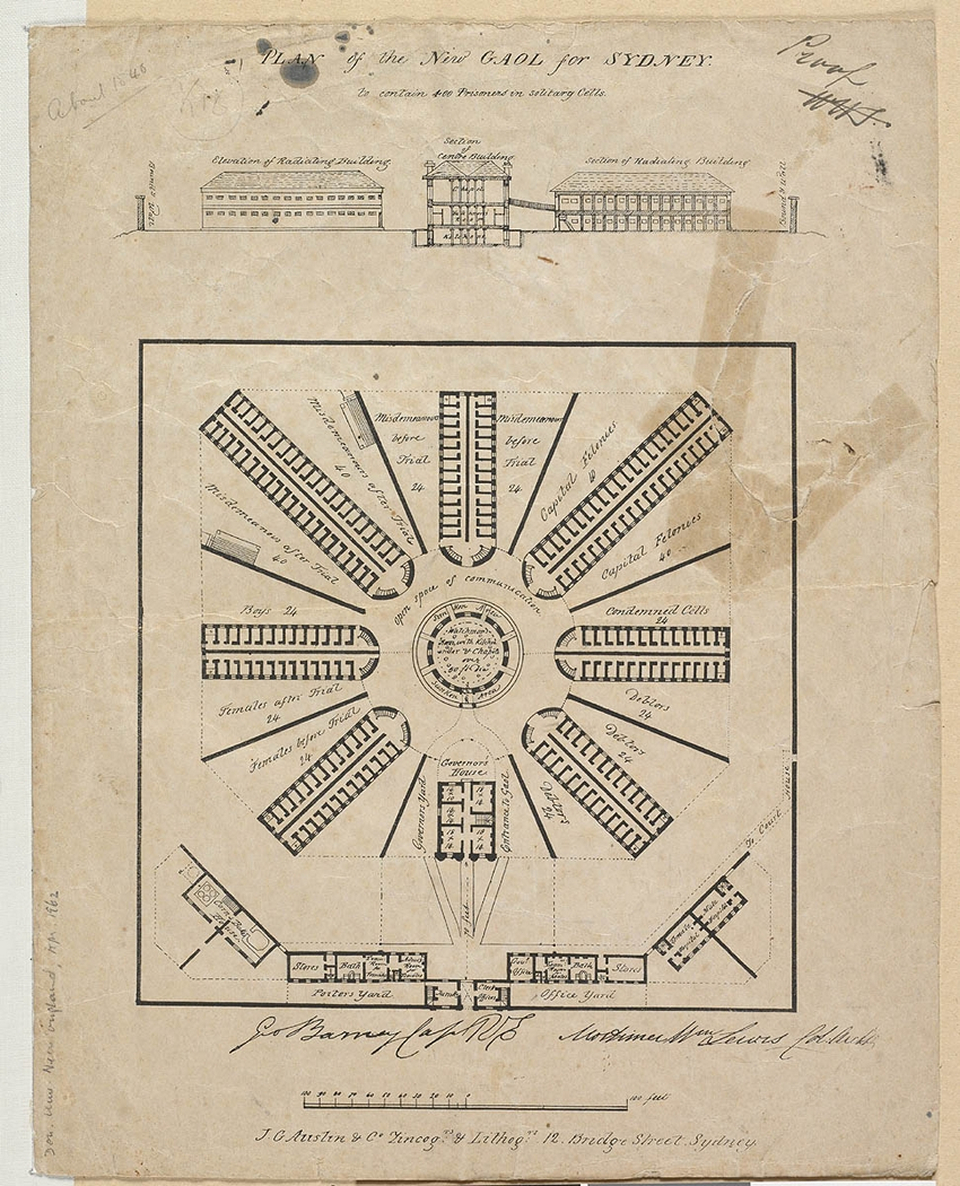

[media]The later designs for the prison, by Mortimer Lewis, were radically altered by George Barney, who arrived to take charge of the project. The gaol represented some of the most progressive ideas of incarceration of the time. It incorporated the view of the British Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline that optimal prison conditions were necessary to ensure reform rather than punishment, and it used Jeremy Bentham's panopticon concept of radial buildings, which allowed for the central surveillance of the prison population. Built partly by convicts, and partly by the free labour of ticket-of-leave tradesmen and others, the gaol symbolised a colonial 'coming of age' in the minds of many. Convict transportation had ceased in 1840 and brought a new emphasis on attracting free settlers to the colony. Treating prisoners more humanely was one element of the much larger endeavour of creating a civil society. [3]

The 1840s saw several major public buildings erected on the South Head Road: apart from the gaol, there was the courthouse and Victoria Barracks. And for all the 'scientific' planning that went into the gaol, the reality was something far more prosaic. In 1841, when the prisoners were marched inside, the buildings were still unfinished. Barney's designs had also been drastically revised by the administration, in order to accommodate even more prisoners. In the original plans each cell was to accommodate one prisoner, but now each cell had to house three. [4] From the start, the gaol was overcrowded, its high-minded design principles compromised by an administration eager to extract the highest return on its expenditure. Outside the walls, near the gaol entrance, effluent and sewerage collected in a huge pond, the stench rising up to greet anyone passing by on the South Head Road. [5]

Inmates

[media]Over the decades it was in operation, Darlinghurst Gaol hosted some significant prisoners, including Bulletin editor JF Archibald and poet Henry Lawson, who did time for drunkenness and non-payment of alimony. Lawson recorded his gaol experience in his haunting 1908 poem 'One Hundred and Three' – his prison number – referring to 'Starvinghurst Gaol' because of the meagre rations given to the inmates.

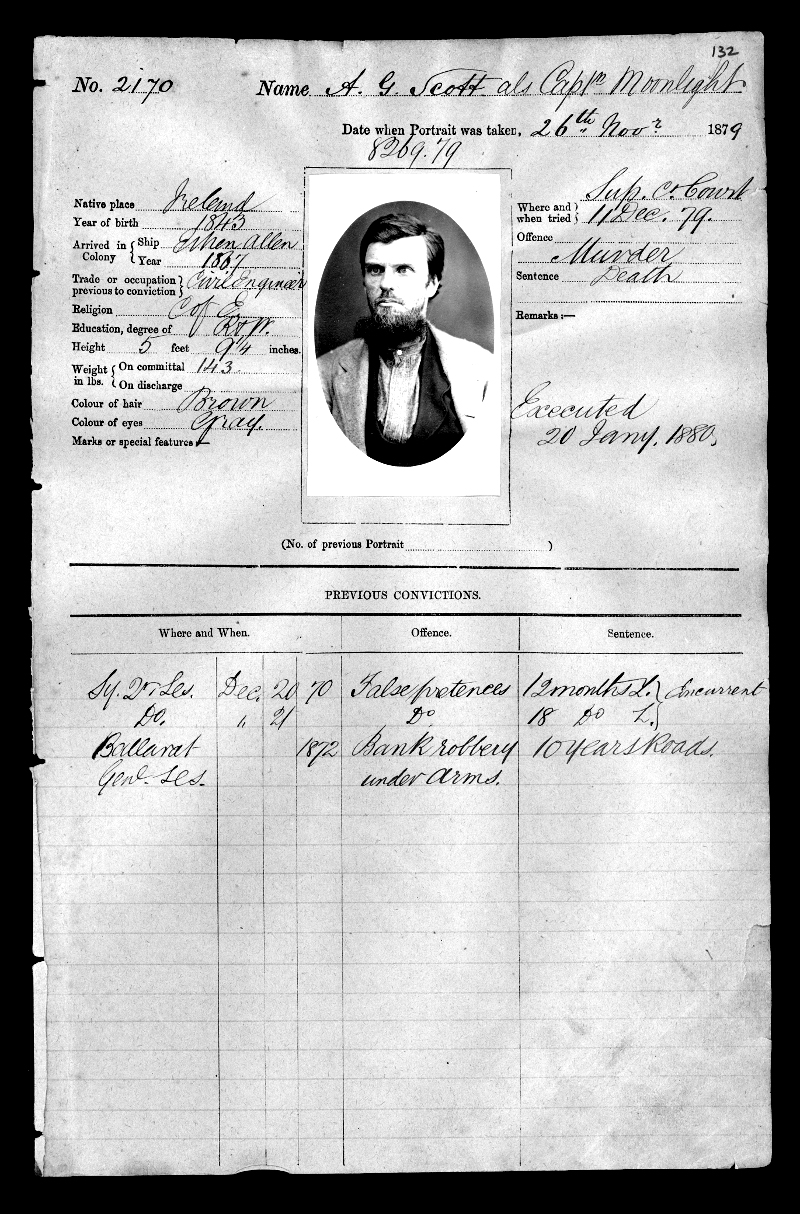

The gaol was also the site for numerous public executions, either on a makeshift gallows outside the main gate in Forbes Street, or as regular 'private' executions on the permanent gallows just inside the main walls near the intersection of Darlinghurst Road and Burton Street. Over the years, a total of 79 people were executed there, including the naval captain, forger, informer and convicted murderer John Knatchbull, hanged in 1844; the [media]notorious bushranger Captain Moonlite, hanged in 1880; Jimmy Governor (immortalised as Jimmy Blacksmith in Thomas Keneally's novel The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith), hanged in 1901; and the last woman to hang in NSW, Louisa Collins, in January 1889.

Over the later decades of the nineteenth century, the prison had become even more overcrowded, with continuous problems with drainage, security and disease. Plans were made for new gaols, and when the 'male penitentiary' was opened at Long Bay, near Malabar in 1914, with lighting in the cells and a prison library, it marked a significant improvement in the conditions and treatment of prisoners in the city's gaols.

Later uses

The old Darlinghurst Gaol was used as an internment camp during World War I, and in 1921 the buildings were converted into the East Sydney Technical College, teaching a range of 'technical' trade courses. Before World War I, 'art' departments were trade-oriented, and 'fine arts' courses were undertaken primarily because of their use in the application of art to industry: thus technical colleges were places with trade drawing classes for engineers, plumbers and metalworkers. But in 1924, all 'art' courses within the technical education system in the state were transferred to the East Sydney Technical College.

In 1921 the National Art School also took up residence in the old gaol buildings and offered diplomas in painting, sculpture, ceramics, design and commercial art. A range of part-time and short courses were also available, and by the early 1960s the National Art School had nearly 500 full-time and 1,000 part-time students and 93 staff. In 1996, the National Art School achieved 'stand alone independence', becoming the sole occupant of the complex of buildings.

The school boasts a prestigious alumni of important figures in the history of Australian art, including James Gleeson, Margaret Olley, Tim Storrier, John Coburn, Ken Done, Max Dupain, Fiona Hall, Alan Jones, Reg Mombassa, Wendy Sharpe, Jeffrey Smart, John Olson and Cressida Campbell, and the sculptor Rayner Hoff.

Also in the complex is the Cell Block Theatre. In the 1950s there was a push to convert part of the building to a theatre. This cause gained significant momentum in 1955 when Katherine Hepburn and Robert Helpmann agreed to visit the Cell Block to announce the project. According to guests at the event, Hepburn made a speech noting how appropriate it was

...that a member of the second oldest profession in the world should open a building which had housed women from the oldest profession.

The venue flourished as a home to avant-garde arts, hosting events as diverse as the Australian premiere of John Cage's Sonatas and Interludes for Piano, concerts by sitar legend Ravi Shankar, and performances from a university student by the name of John Bell. Since the 1980s the theatre has served primarily as a venue for the Art School's formal gatherings and as exhibition space for student works.

Darlinghurst Gaol is the oldest surviving large gaol complex in Australia. It is well designed and largely intact; constructed entirely of sandstone; the workmanship is extremely good. Its chapel is considered one of the finest examples of the stonemason's art in Australia.

References

Clive Faro, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

Deborah Beck, Hope in hell: a history of Darlinghurst Gaol and the National Art School, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest NSW, 2005

The Thin Blue Line website, 'The Old Darlinghurst Gaol', www.policensw.com/info/history/darlgaol.html , viewed 17 February 2009

National Art School website, 'History', http://www.nas.edu.au/History.htm, viewed 17 February 2009

Notes

[1] Brisbane to Bathurst, 14 May 1825, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 11, p 582; Oxley to Darling, 22 March 1827, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 13, p 367; Darling to Huskisson, 27 May 1828, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 14, pp 202–3; and Darling to Huskisson, 29 August 1828, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 14, pp 352–3

[2] Sydney Gazette, 30 April 1835, 12 January 1836 and 14 January 1836; Sydney Gazette, 6 December 1836

[3] Report from the Committee on the Gaol at Darlinghurst, New South Wales Legislative Council Votes and Proceedings, 1836; Australian, 17 June 1841 and 24 August 1842; Sydney Morning Herald, 9 January 1914 and 18 December 1913; Daily Telegraph, 24 March 1923. JS Kerr, Design for convicts; Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1984; JS Kerr, W Thorp, C Burton and G Brooks, East Sydney Technical College Conservation Masterplan, Sydney, 1989

[4] Australian, 10 September 1840

[5] Australian, 24 August 1842; Report from the Select Committee on the Public Prisons in Sydney and Cumberland, New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, 1861, vol 1, pp 1027–1310

.