The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Second Fleet

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Second Fleet

The Second Fleet was a term later applied to the second wave of British convict transports and storeships sent to the newly established colony of New South Wales in 1789–90, about two years after the departure of the First Fleet in 1787. The despatch of the First Fleet had done little to alleviate the problem of overcrowding in Britain's gaols and hulks. The government was unable to send more convicts to the colony until word arrived from Governor Arthur Phillip that the new colony had survived. Once this was received, a second fleet was assembled and despatched. [1]

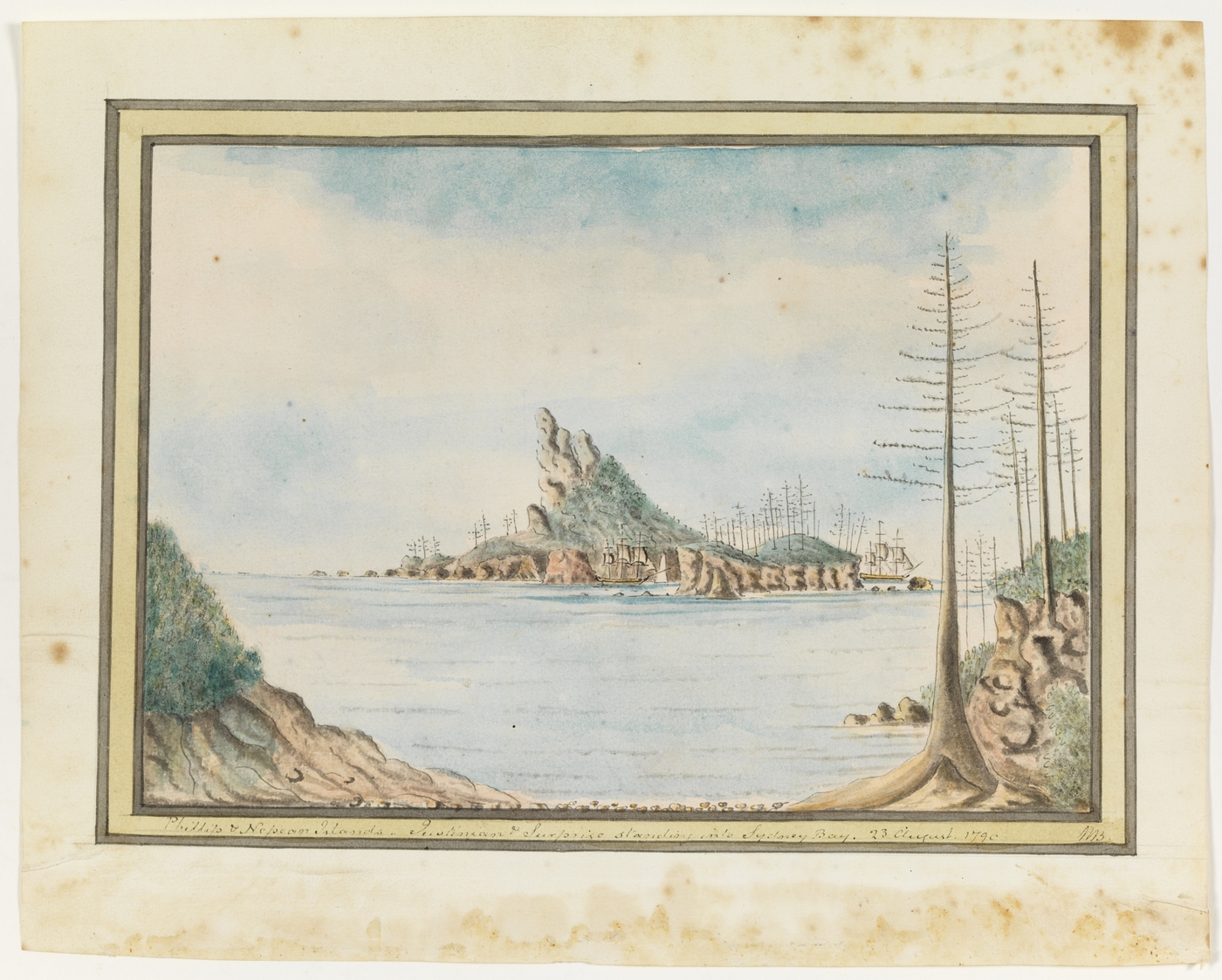

[media]The group included the female convict transport Lady Juliana, chartered from private shipping merchants; the naval warship Guardian, carrying stores for the colony; and the storeship Justinian and transports Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize, chartered from private shipping merchants, carrying mostly male and a small number of female convicts.

[media]The ships sailed in three stages in differing contexts, but all arrived in the colony during June 1790 (except Guardian, which struck an iceberg in the Southern Ocean).

Their voyages were very different. The Lady Juliana left first and made the longest voyage, but arrived with a relatively healthy group of women convicts. Of 928 male convicts on Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize, 26 per cent died on the voyage and nearly 40 per cent were dead within eight months of their arrival in the colony. This shocking mortality rate – nearly ten times that of the First Fleet voyage –prompted the government to enact changes to the system of transporting convicts to avoid a repeat of what was later tagged the 'Death Fleet'.

The Lady Juliana

Only 193 women had sailed on the First Fleet during 1788, and high numbers of female prisoners, especially at London's Newgate Gaol, remained an acute problem because women could not legally be sent to prison hulks.

As a stopgap, the First Fleet contractor William Richards Jr was asked to hold women in a ship on the Thames until news from New South Wales was received. About 230 women were embarked and managed under the supervision of Thomas Edgar as a naval agent (the government official monitoring the captain and crew contracted to transport the women), eventually spending nearly six months on the river. Four women escaped the night before the vessel left London on 20 June 1789, at least two of them desperate to be reunited with children left behind. The husband of one escapee rowed them to shore while other convicts distracted the watchman with gin, singing and 'making fun'. After further delay, the Lady Juliana left English waters from Plymouth on 29 July 1789.

A memoir written in the 1820s by [media]the ship's Scottish steward John Nicol describes the voyage on which, he wrote, every man on board formed a consensual relationship with a woman who became his 'sea-wife'. Such partnerships were common on female convict ships in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

A letter from an unnamed woman who sailed on the Lady Juliana was published in London's Morning Chronicle on 4 August 1791, providing a rare woman's voice in the public domain and expressing what seems to have been a generally favourable view of their treatment:

We arrived here safe after a long voyage, thanks to our good agent on board, and the gentleman in England who sent us out, as we had everything that we could expect from them, and all our provisions were good.

The length of the voyage (more than 11 months) raised eyebrows at the time and in 1959 the maritime historian Charles Bateson referred to the ship as 'a floating brothel'. The ship was a poor sailer and required extensive repairs at three ports of call, Tenerife, Rio di Janeiro and Cape Town, where the women received the benefit of fresh meat and vegetables which improved their health. They were also supplied with tea, sugar and soap and the death rate of 2 per cent (five convicts died on the voyage) was low.

The ship's arrival at Port Jackson on 3 June 1790 with news that stores were on the way was greeted with joy by the near-starving colonists; 'News burst upon us like meridian splendour upon a blind man', wrote Captain Watkin Tench.

A seaman who saw the convicts land said: 'they were all fresh, well looking women'. [2] They raised the ratio of women in the colony from about 20 per cent to 40 per cent, a level not equalled for decades. Seven children were born on the voyage and many more in the months after landing. A British newspaper commented facetiously:

The female convicts carried to Botany Bay, by the Lady Juliana transport, were delivered very soon after their arrival of thirty-seven children, the exact number of men in the ship!

[media]Many of the Second Fleet women became mothers of the rising emancipist generation, among them Catherine Crowley. Her son, the future politician William Charles Wentworth was conceived on Neptune with D'Arcy Wentworth, who sailed as a free surgeon after narrowly escaping a conviction in London as a gentleman highwayman.

Vital stores for the colony

In September 1789 the naval warship HMS Guardian sailed for New South Wales after being fitted out as a storeship. Phillip had requested more supplies for the near-starving colony and skilled personnel. The ship was loaded with stores, plants and stock, but struck an iceberg in the Southern Ocean on the last leg of the voyage on Christmas Eve 1789. Part of the crew abandoned ship, but her commander, Lieutenant Edward Riou, succeeded in a desperate bid to save the vessel and barely made it back to Cape Town where the ship was beached. It was a disaster for the colony, where further cuts to rations were made in 1790, to preserve dwindling food supplies.

A storeship, Justinian, [media]was supplied by another contractor to carry government stores. A portable military hospital, dismantled into 602 pieces, was also taken on board.

Contracts and incentives

Meanwhile British gaols continued to overflow. The government acted quickly to make arrangements for three ships to carry 1000 convicts, along with farm implements, tools, medicines, clothing, books and food. The Navy Board rejected a bid from William Richards Jr, who was displaced as transportation contractor by the slave-trading firm Camden, Calvert & King.

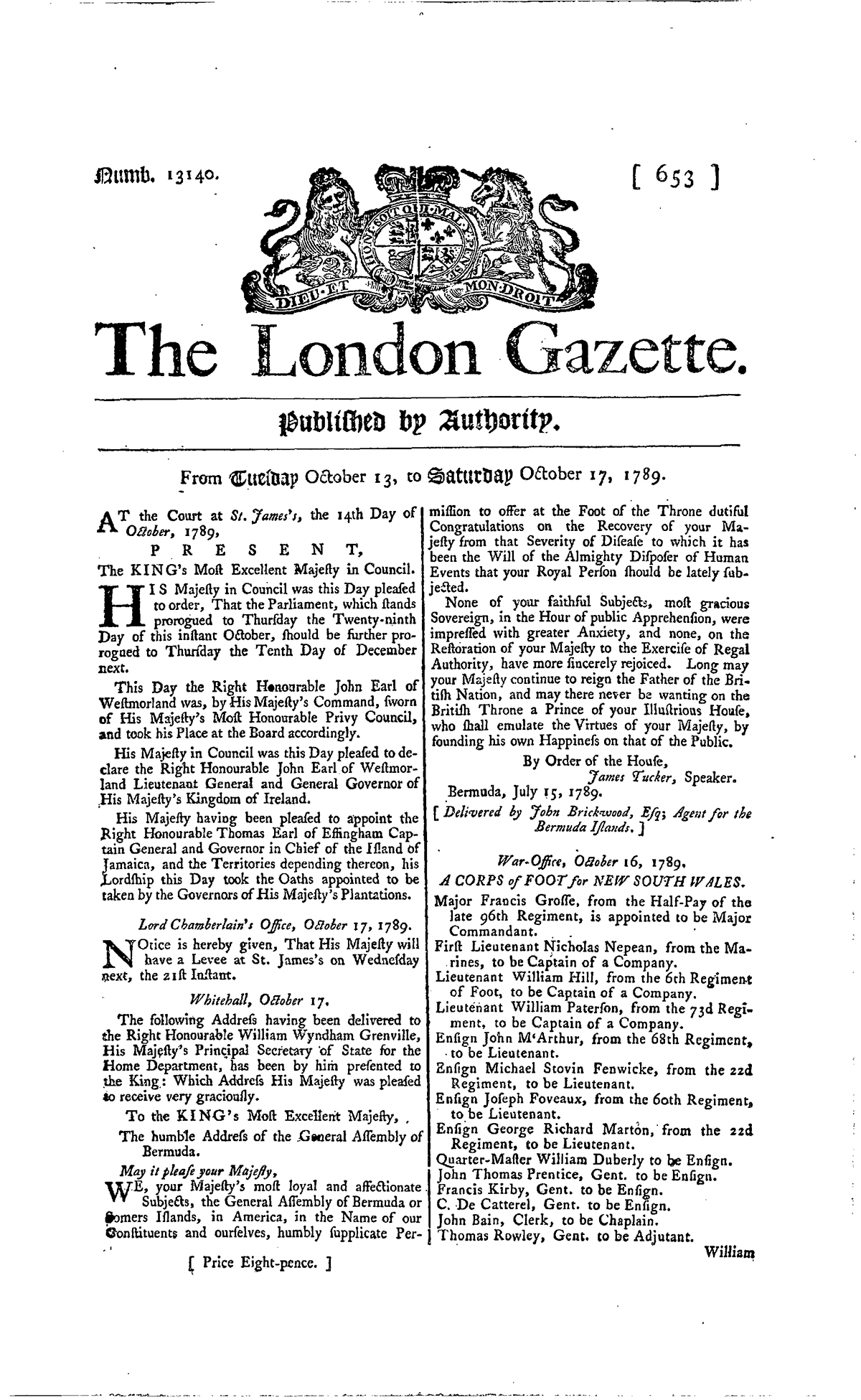

The change coincided exactly with the resignation of Lord Sydney as Home Secretary and his replacement in June 1789 by William Wyndham Grenville. Aged 29, Grenville was an energetic new minister interested in cost cutting and efficiency. The lower tender seemed a quick, cheap solution to the gaol problem after the huge expense of the First Fleet.

Evan Nepean, the permanent Undersecretary at the Home Office who had done much to make the First Fleet a success, remained in office, but was incapacitated by illness for part of 1789, leaving oversight of the fleet to a less experienced colleague. George Teer and Joshua Thomas, both veteran Navy Board officials who had handled arrangements for the First Fleet both died in mid-1789. Their work was done by James Bowen, an inexperienced man in his late twenties. [3]

In August 1789 a representative of Camden, Calvert & King signed a contract with the Navy Board in which he agreed to supply three ships to convey 1000 convicts, their military guard and stores to the colony. He was to ensure the ships were in good condition, fully fitted up for sea under the direction of naval officials with secure accommodation for the convicts including irons and handcuffs, cooking equipment, bedding, cutlery, lamps etc. The captains were required to obey the orders of the naval agent (Lieutenant John Shapcote, aged 50) who would sail with them to monitor compliance with the contract and were given permission by the East India Company to bring back a cargo of tea from China.

The contractors were to be paid a sum of £17.7.6 for each convict embarked. Of this sum £5 was to be paid when the ship was fitted up, £10 when the stores were loaded and the remainder when the NSW Commissary certified that the stores had been delivered. The contract gave the firm a financial incentive to land the stores safely, but gave no encouragement for the convicts to be landed alive and healthy.

Boarding the fleet

During October and November 1789, convicts were embarked on the Neptune (about 502 convicts: 424 male and 78 female, Surprize (254 men) and Scarborough (253 men). Donald Trail, captain of Neptune, a crusty Scot from Orkney, was a former navy master who had also commanded a slave ship for the contractors. Nicholas Anstis, master of Surprize, was an Irishman who was also a former navy master, and had sailed with the First Fleet as first mate on Lady Penrhyn. John Marshall, captain of Scarborough, had previously sailed Scarborough on the First Fleet voyage.

[media]About 114 soldiers of the newly formed New South Wales Corps and about 10 of their wives and 10 children were ordered to sail with the ships, along with six free wives of convicts and a small group of convicts’ children. As the ships moved around the coast, disputes soon arose between the ship captains and army officers on board over who had primary authority over the convicts. Neptune's initial master, Captain Thomas Gilbert, fought a bloodless pistol duel with Lieutenant John Macarthur at Plymouth and was replaced by Donald Trail. [media]The duel caused a sensation in the newspapers and though the army officers managed to remove Gilbert, they were forced to acknowledge that the ship captains and naval agent had authority over the convicts at sea.

Captain William Hill, a genteel but irascible army officer, had a similar conflict with Anstis on Surprize and wrote a series of letters home, declaring 'The slave trade is merciful compared with what I have seen in this fleet'. He complained of the need for:

a controlling power in each ship over these low-lifed, barbarous masters, to keep them honest … it is impossible to suppose that men bred up Gentlemen must be obliged to herd against their Inclinations with a set of men who for the Most Part are so illiterate and uneducated as not to be able to write their names – so that they cannot behave with good manners from a total Incapacity.

His view was echoed and amplified by the First Fleet officer Captain Watkin Tench in his book on the colony, who wrote that the ship captains and contractors had:

violated every principle of justice, and rioted on the spoils of misery, for want of a controlling power to check their enormities.

Justinian sailed separately from the others and left English waters off the Cornish coast on 17 January 1790, calling only at St Jago and reaching Port Jackson on 20 June after a voyage of 154 days. The three transports sailed in company, reconnoitred off Portsmouth, and also left England on 17 January, reaching Port Jackson between 26 and 28 June.

Scurvy, starvation and death

The voyage was a disaster. In February, a convict alleged that convicts were planning to rise up and take Scarborough. As a consequence, male convicts on all three ships were kept chained for longer periods and allowed less exercise than the convicts of the First Fleet. Sixty-eight had died (mostly from scurvy and most of them convicts) by the time the ships reached Cape Town on 13 April. There, Riou, master of Guardian, negotiated with Shapcote, the naval agent, who reluctantly accepted some of the salvaged stores from the disabled Guardian, making the ships even more crowded. Riou thought Shapcote was incompetent and beholden to Trail and reported in a tone of exasperation that:

if ever the navy make another contract like that of the last three ships they ought be shot and as for their agent Mr Shapcote he behaved here just as foolishly as a man could well do.

[media]The agent was also ailing and died in his cabin in the presence of his convict mistress two weeks after Neptune left Cape Town on 29 April. By the time the ships reached Port Jackson a total of 256 male convicts and 11 women had died, with a large percentage of the remainder in poor health from scurvy and infectious fevers, with 124 hospitalised on arrival. Only about 25 per cent were in reasonable health.

The First Fleet's chaplain, the Reverend Richard Johnson, left a powerful eyewitness account of the landing of the convicts on 26–28 June 1790, at the colony's first wharf, a natural rock formation just north of Cadman's Cottage, where the Overseas Passenger Terminal now stands [4]:

I beheld a sight truly shocking to the feelings of humanity, a great number of them laying, some half, others nearly quite naked, without either bed or bedding, unable to turn or help themselves. Spoke to them as I passed along, but the smell was so offensive that I could scarcely bear it…. The landing of these people was truly affecting and shocking; great numbers were not able to walk, nor to move hand or foot; such were slung over the ship side in the same manner as they would a cask, a box, or anything of that nature. Upon their being brought up to the open air some fainted, some died upon deck, and others in the boat before they reached the shore. When come on shore many were not able to walk, to stand, or stir themselves in the least, hence some were led by others. Some creeped upon their hands and knees, and some were carried upon the backs of others.

The unnamed Lady Juliana convict whose letter appeared in the Morning Chronicle gave another poignant account of the arrival of the unlucky convicts of the Neptune and her two sister ships:

Oh! If you had but seen the shocking sight of the poor creatures that came out in the three ships it would make your heart bleed they were almost dead, very few could stand, and they were obliged to fling them as you would goods, and hoist them out of the ships, they were so feeble; and they died ten or twelve a day when they first landed; but some of them are getting better … They were not so long as we were in coming here, but they were confined, and had bad victuals and stinking water. The Governor was very angry, and scolded the captains a great deal, and, I heard, intended to write to London about it, for I heard him say it was murdering them. It, to be sure, was a melancholy sight. What a difference between us and them.

Scandal and litigation

Many of the crewmen on the fleet had deserted. As the ships arrived back in England from September 1791, newspapers reported on the great mortality among the convicts in shocked tones. In November a London lawyer, Thomas Evans, who specialised in acting for seamen recovering lost wages, mounted a private prosecution of Trail and his chief mate William Ellerington in the London courts, alleging that their ill-treatment of the ship's Portuguese cook had caused his death and was tantamount to murder. He also made a series of allegations about the mistreatment of the convicts and crew, based on evidence he collected from seamen on the ships, alleging that the mortality had been caused by the convicts being starved by the contractors in order to defraud the government and increase profits from the voyage.

Shocking details were published describing physical abuse of crew and convicts, the brutal use of irons, convicts concealing deaths of their messmates to collect their rations and eating oatmeal poultices from dead bodies, adding that on arrival Trail had sold rations left unconsumed because of the mortality at exorbitant prices. One sailor claimed he had heard Governor Phillip say the Neptune should be renamed the Wilful Murder. [5] The Governor wrote to Grenville:

I will not, sir, dwell on the scene of misery which the hospitals and sick tents exhibited when those people were landed, but it would be want of duty not to say that it was occasioned by the contractors having crowded too many on board these ships, and from their being too much confined during the passage.

The Navy Board was embarrassed and on the defensive. Documents tending to favour the contractors were tabled in the House of Commons when the matter was raised in February 1792. Trail had absconded to Belgium, but returned to face trial with Ellerington in the High Court of Admiralty for the murder of the ship's cook when the Attorney General made the private prosecution a public one. Both were acquitted in June and Evans was recommended to be struck off the roll of solicitors for prejudicing the case with handbills and news stories.

There remained a degree of concern over the fiasco within government, probably over what degree or combination of incompetence, negligence or corruption was involved in preparations for the despatch of the Second Fleet. In theory, the job of the Navy Board was to ensure that the convicts were transported safely but an unacceptable level of overcrowding had been allowed to occur which was exacerbated by difficult weather conditions and the contractor's attempt to shorten the voyage by stopping at one port only for fresh provisions, whereas the First Fleet had stopped at three.

In July 1792 the Attorney General and Solicitor General reported to the King, recommending an inquiry because of:

the consistency of the great number of witnesses who speak to these points tend strongly to criminate the Contractors and also the officers of the Navy Board.

Camden Calvert & King's Third Fleet ships had already sailed. No other action was taken against them or, as far as can be ascertained, against any public official. The Second Fleet mortality had one good effect. A system of incentive payments paid on the number of convicts landed alive was introduced which eventually contributed to a fall in the death rate on convict voyages.

Further reading

Accounts and Papers Relating to Convicts on Board the Hulks, and Those Transported to New South Wales', ordered to be Printed 10th and 26th March 1792. House of Commons Sessional Papers of the Eighteenth Century, (83)

1791-92.

Bateson, Charles. The Convict Ships, 1787–1868. Sydney, Library of Australian History, 1983.

Britton, Alexander (ed). Historical records of New South Wales. Volume 1, Part 2. Phillip, 1783–1792. Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer: 1892–1901.

Britton, Alexander. History of New South Wales from the Records: Phillip and Grose, 1789–1794. Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer, 1894.

Cobley, John. The Crimes of the Lady Juliana Convicts, 1790. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1989.

Collins, David. An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales; With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. Vol 1, 1798. Edited by H Fletcher. Sydney: AH & AW Reed in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1975.

Flynn, Michael C. The Second Fleet: Britain's Grim convict Armada of 1790. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1993.

Nicol, John. John Nicol, Mariner: Life and Adventures 1776–1801. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 1997.

Rees, Siân. The Floating Brothel. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2010.

Sturgess Gary, L & Cozens, Ken, 'Managing a Global Enterprise in the Eighteenth Century: Anthony Calvert of The Crescent, London, 1777–1808,' The Mariner's Mirror, 99, Issue 2 (2013): 171–195.

Tench, Watkin. Sydney's First Four Years; being a reprint of A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson. Introduction and annotations by LF Fitzhardinge. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1979.

Notes

[1] Unless otherwise stated, all references for this item are given in Michael Flynn, The Second Fleet: Britain's grim convict armada of 1790 (Sydney, Library of Australian History, 1993), 1–65. References from The National Archives, London, and National Maritime Museum, London supplied by Gary L Sturgess from his research: see www.convicts.sturgess.org.

[2] Ham Rust Examination, 'Examinations and Depositions of the several Sailors…of the Ship Neptune', The National Archives, London TS11/381, TS11/381, 37

[3] Middleton to Pitt, rough draft, May 1789, John Knox Laughton (ed.), Letters and Papers of Charles, Lord Barham, 1758-1813 (London: Naval Records Society, 1910), vol II, 305–09, 322, 326; On Teer – Teer to Middleton, 25 April 1789, National Maritime Museum, London MID/1/184; Teer to the Navy Board, 1 June 1789, The National Archives, London ADM106/243; Minutes of the Navy Board, 29 June 1789, The National Archives, London ADM106/2630; Minutes of the Navy Board, 25, 29 & 30 June 1789, The National Archives, London ADM106/2630. Bowen's first correspondence in his new role is dated 2 July – Bowen to Navy Board, 2 July 1789, The National Archives, London ADM106/243.

[4] Michael Flynn and Gary Sturgess, 'New Evidence on Arthur Phillip's First Landing Place – 26 January 1788', History: Magazine of the Royal Australian Historical Society no 122 (December 2014): 3–5, available online at:http://www.rahs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/New-Evidence-Online-Version1.pdf

[5] Statements of Thomas Bishop, Robert Fletcher and Ham Rust at 'Examinations and Depositions of the several Sailors … of the Ship Neptune', The National Archives, London TS11/381, 29–30, 37, 63.

.