The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Parramatta and Black Town Native Institutions

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Parramatta and Black Town Native Institutions

The Parramatta and Black Town Native Institutions existed from 1814 till 1829 as part of a campaign, led initially by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, to extend enlightenment ideals to the Indigenous peoples of the Sydney colony. Their stories can be found in the remaining colonial archive carefully studied by Brook and Kohen and, in recent years, enriched by greater appreciation of local and family oral history. The Native Institution was designed to inculcate European ideas of 'civilisation', commerce and Christianity into Aboriginal people and turn them into industrious workers. [1]

Background to the Native Institution

Colonisation brought widespread social disruption for the Eora and Cadigal people from 1788 and for the Cumberland Plain people to the west a few years later. The smallpox epidemic that caused massive casualties in the east in the opening years of the colonial occupation – only a handful of Cadigal people were reported to have survived by 1791 – is also likely to have dramatically impacted people west of the new colony, out to the Nepean River. [2]

European explorers in 1789 and 1790, journeying beyond the settled colony to the west and north-west, noted the presence of Aboriginal people. On one occasion, while accompanied by coastal people Colebee and Burraberongal, the exploring party was greeted by Gombeeree, his son Yarramundi and grandson Deeimba, along with their respective wives, while children watched from the banks. At this meeting, Gombeeree presented hunting equipment to the Governor, suggesting an amicable, cooperative resource exchange. But with ever-encroaching settlements rapidly depleting resources and traditional hunting grounds, any trust and goodwill evaporated.

By 1791, at Prospect Hill, conflict between Aboriginal people and settlers saw a musket fired and a convict hut burned to the ground in retaliation. A decade later, in May 1801, Governor King authorised firing on Aboriginal people to drive them well away from the European settlements at Parramatta, Prospect Hill and Georges River, further dislocating people from their traditional lands. When the settlement further west at Mulgoa suffered severe drought in 1814, and crops withered on stripped traditional hunting grounds, a state of frontier warfare broke out to the west of the colony.

To quash the uprising, Governor Macquarie dispatched three military parties in April 1816 to Cowpastures, Airds and Appin. With a list of the names of known offenders and Aboriginal guides (Nurragingy, alias 'Creek Jemmy' of the 'South Creek tribe', and Colebee of the 'Richmond tribe' among them), they set forth to drive the 'marauding blacks over the mountains' and capture offenders. They had instructions to protect innocent women and to procure Aboriginal children for the Parramatta Native Institution. As part of a promised peace, Macquarie offered land grants for Aborigines who agreed to settle and cultivate assigned small lots. This gesture amounted to significant recognition of Aboriginal rights to land, despite its limited nature and misunderstanding of Aboriginal land usage. A grant of land was subsequently made to Colebee and Nurragingy.

Establishing the Black Native Institution at Parramatta

By 1814 Macquarie turned his attention, no doubt with consideration of the frontier conflict on the western edge of the colony, to establishing a 'Black Native Institution' at Parramatta. Macquarie's 'General Orders', as outlined in December 1814, acknowledged the loss of livelihood Aboriginal people had suffered and the need for a humane response. Correspondence from William Shelley of the London Missionary Society outlined ambitions to 'improve' and 'civilise' students through instruction in reading, writing and religion, training in manual labour for the boys and useful needlework for the girls, and the plan for the School was born. Shelley was appointed superintendent and principal instructor of the Native Institution at Parramatta, the first of its kind in the colony. His death on 6 July 1815 left his wife, Elizabeth Shelley, to run the new school, which she did until 1826. The Native Institution aimed 'to effect the civilisation of the Aborigines' of NSW and to 'render their habits more domesticated and industrious'.

Governor and Mrs Macquarie were the School's patrons and there was a seven-member committee including such notables as John Thomas Campbell, D'Arcy Wentworth, William Redfern, Hannibal McArthur, and the clergymen William Cowper, Henry Fulton and Rowland Hassall. The colony's chaplain, Reverend Samuel Marsden, was a notable exclusion owing to his opposition to Macquarie's 'civilising' mission.

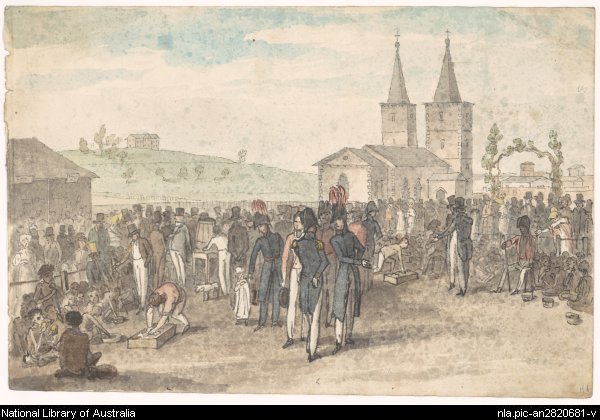

[media]The first 'Public Conference with all those tribes of the Natives of [NSW] residing in the Colony' at the marketplace in Parramatta on 28 December 1814, 'the day after the full moon', with a 'feast' of roast beef, bread and jugs of ale, was intended to recruit students by communicating the aims and purpose of the Native Institution along with plans to offer land grants for settled industrious adults. [3] Four students were enrolled from the conference, taking the number to eight; another two boys enrolled in June 1816 although only briefly; in August 1816 nine new children were enrolled and in September a baby boy came to the Institution.

At the 1816 'friendly meeting of all Natives', rewards such as blankets, clothes, and shoes were inaugurated. [4] The Governor awarded breastplates to 'Meritorious Natives', attempting to select and empower 'chiefs', and land grants were offered. Before the crowd of 179 men, women and children, the Native Institution students walked in procession to the marketplace gathering. The next year's gathering saw 16 students paraded before reportedly proud families. [5] The Conference and feast of December 1818 attracted a crowd of 300 Aborigines including some from over the mountains and from distant north and south lands, with some participants painted in red and white ochre – but no children were handed over to the school at this time.

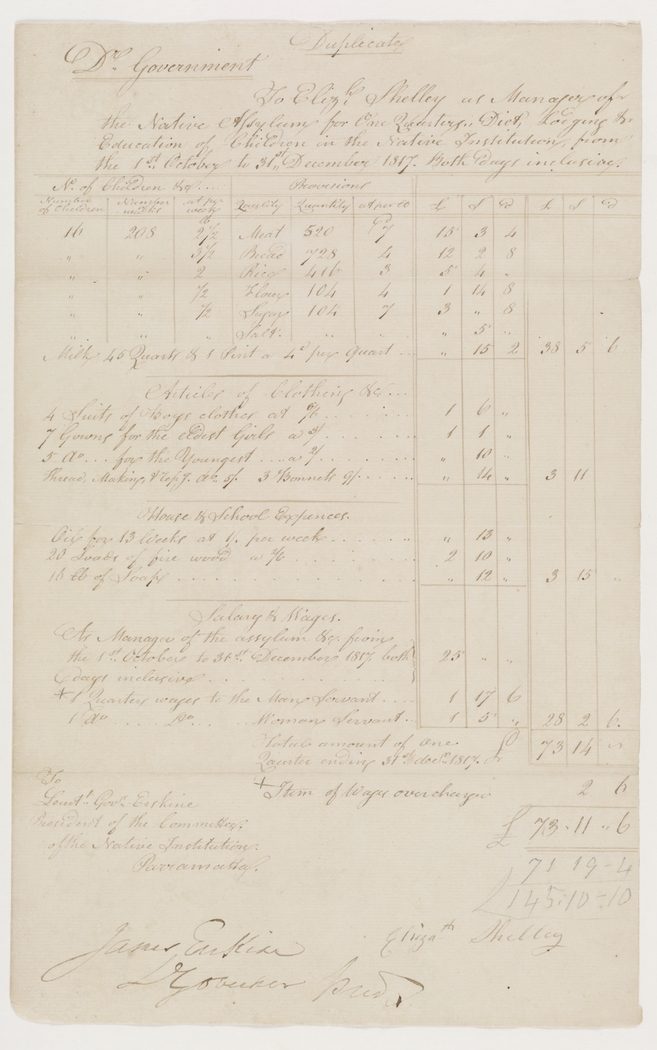

[media]Over the life of the Parramatta Native Institution from January 1814 to December 1820, a total of 37 students were enrolled. Most stayed only for a short time before making their way back to their families. In September 1818 the number of children enrolled at the Native Institution swelled to 19; by the annual conference and feast of 1819 another three children had enrolled and by the end of 1820, 20 students were enrolled – the highest number of concurrent enrolments in the history of the Institution. By 1822 a more regular number of 13 children continued to be schooled at Parramatta. [6] In August 1821 several of the children died, which produced a strong feeling among the other Aboriginal children that they should get away from the place. Many students fled the Institution.

Aboriginal parents had resisted the school and pined for their children from the beginning – an open slat fence was built early in 1815 to provide parents the requested opportunity to gaze upon their children while at school. Shelley, before his early death in 1815, noted the reluctance of Aboriginal parents to give up their children and Yarramundi spoke of the fear of 'men in black clothes' taking the children to the Institution in 1818. [7]

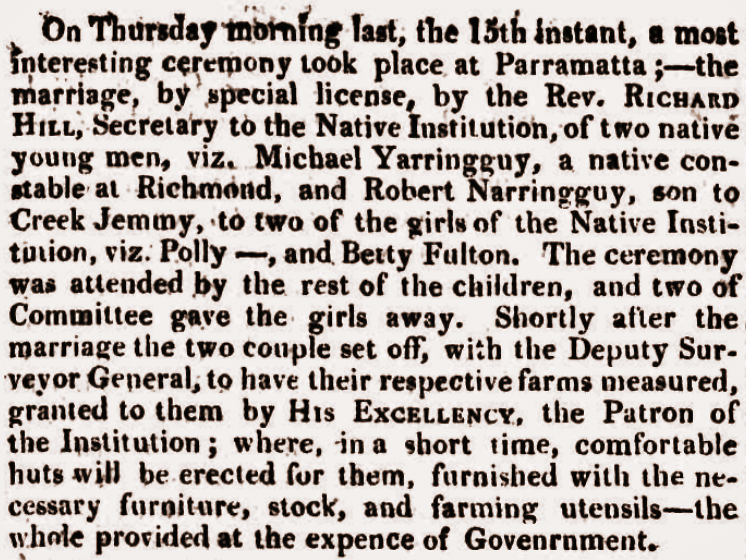

The low enrolments did not seem to deter Macquarie: he wrote glowingly of the School's success, including its role in conciliating Aboriginal people. Maria Lock's academic success and the celebration of the [media]marriages of two students to eligible Aboriginal men (those showing European aptitude) were cited as successes for the project. The married couples were subsequently granted land along the Richmond Road and supplied with a comfortable hut and domestic fittings. Eventually five families were settled on the south side of Richmond Road close to where Nurragingy continued to live.

Macquarie's final conference and feast in December 1821, where he introduced his successor Sir Thomas Brisbane, drew the biggest crowd of 340 Aboriginal men, women and children.

The Black Town Native Institution

In August 1820 William Walker of the Wesleyan Mission Society was appointed missionary to the 'Black natives of [NSW]', the first minister of any denomination to be solely responsible for Indigenous Australians. [8] From 1822 Walker found an ally in Governor Brisbane, to whom he conveyed his vision for a large, thriving, self-sufficient settlement at Black Town with instruction in both agriculture and Christianity. However, the presence and activity of the Wesleyan Mission Society was less than enthusiastically received by the established Anglican church and its chaplain to the colony, Reverend Marsden, who had joined the Native Institution committee after Macquarie's departure. He was more impressed with the Māori people than Sydney Aboriginal people and at other times advocated more direct involvement by the Anglican Christian Missionary Society in Aboriginal lives. Intra-religious factions played a significant role in the history of the Black Town Native Institution and also reflected government politics.

By the end of 1823 a large Native Institution Mission House and chapel, six small cottages and some outbuildings had been built along the Richmond Road adjacent to Colebee and Nurragingy's 1819 land grant. Ten years later, in 1833, the Native Institution at Black Town was abandoned, following low and fluctuating student enrolment and changing management and religious and governmental ambitions. However, the site has enormous significance in the history of Aboriginal and European contact. It is of enduring importance for Aboriginal people who trace their traditional ancestry and social history to the Black Town Native Institution site and of broader significance in understanding the politics of the colonial administration. Its story illustrates the clash of cultures and the active and passive forms of resistance used by Aboriginal people that perplexed and disappointed the Europeans.

In the absence of Macquarie's care and enthusiasm for Aboriginal people, there was little genuine religious or government interest in the Black Town Institution. The Clarke family, who oversaw the construction of the Mission School and buildings from June to September 1823 were, by the end of the year, eager to depart for their appointment to Kerikeri Mission in New Zealand, as their interest in Māori customs, culture and rights was much greater.

In 1824 Governor Brisbane sacked Samuel Marsden and his colleagues on the Native Institution committee. The children attending the Black Town Native Institution were subsequently divided up between the established church and the Wesleyan Methodists. William Walker, who had been operating the Wesleyan Mission House in Parramatta and tutoring several Aboriginal children, returned to Black Town. The Aboriginal population at Black Town increased: in 1824, 10 adults and 13 children were provided for, increasing to 30 by early 1825. [9]

In 1825 Governor Brisbane announced the closure of the Native Institution at Black Town. His decision to do this is perplexing but is perhaps best understood through the events that subsequently unfolded: William Walker was placed in charge of the amalgamated Native and Female Orphan Institution at Parramatta. The residents at Black Town were abandoned to their fate in a battle between the colonial church and the Methodists.

The new Governor, Ralph Darling, had different ideas again and renewed Macquarie's earlier ideas that Aboriginal people should become 'the objects of civilisation and conversion to Christianity'. The Reverend Frederick Wilkinson was initially appointed to head up an Aboriginal Infants' School at the Black Town Mission House site and the Native School was resurrected. Ambitions to establish more Native Schools were thwarted by the small numbers of children and so Black Town became the sole school. Children were transferred back to the Black Town Native School, now under the management of William Hall: six girls from the Female Orphan School, boys from the Male Orphan School at Liverpool and three Māori students were enrolled as well. By 1827 there were 14 students enrolled and, by September of that year, 17 Aboriginal students and five Māori students. In 1829, six Aboriginal children and five Māori children continued instruction at the school. Under Hall's administration the school was less successful: the Institution suffered with the dire economy and worsening environmental conditions of the colony. Drought limited their harvest and their livestock were depleted and emaciated. Their limited resources were stringently rationed and the Native Institution was increasingly fortified to secure what little they had from both hungry students and outsiders. Venereal disease caused the deaths of several of the children at this time. By January 1829 the resurrected Native Institution was permanently abandoned and the remaining 10 children transferred to the care of Reverend Cartwright at Liverpool who, reluctant to continue to care for the children, had them reassigned to the Wellington Valley Mission in 1833.

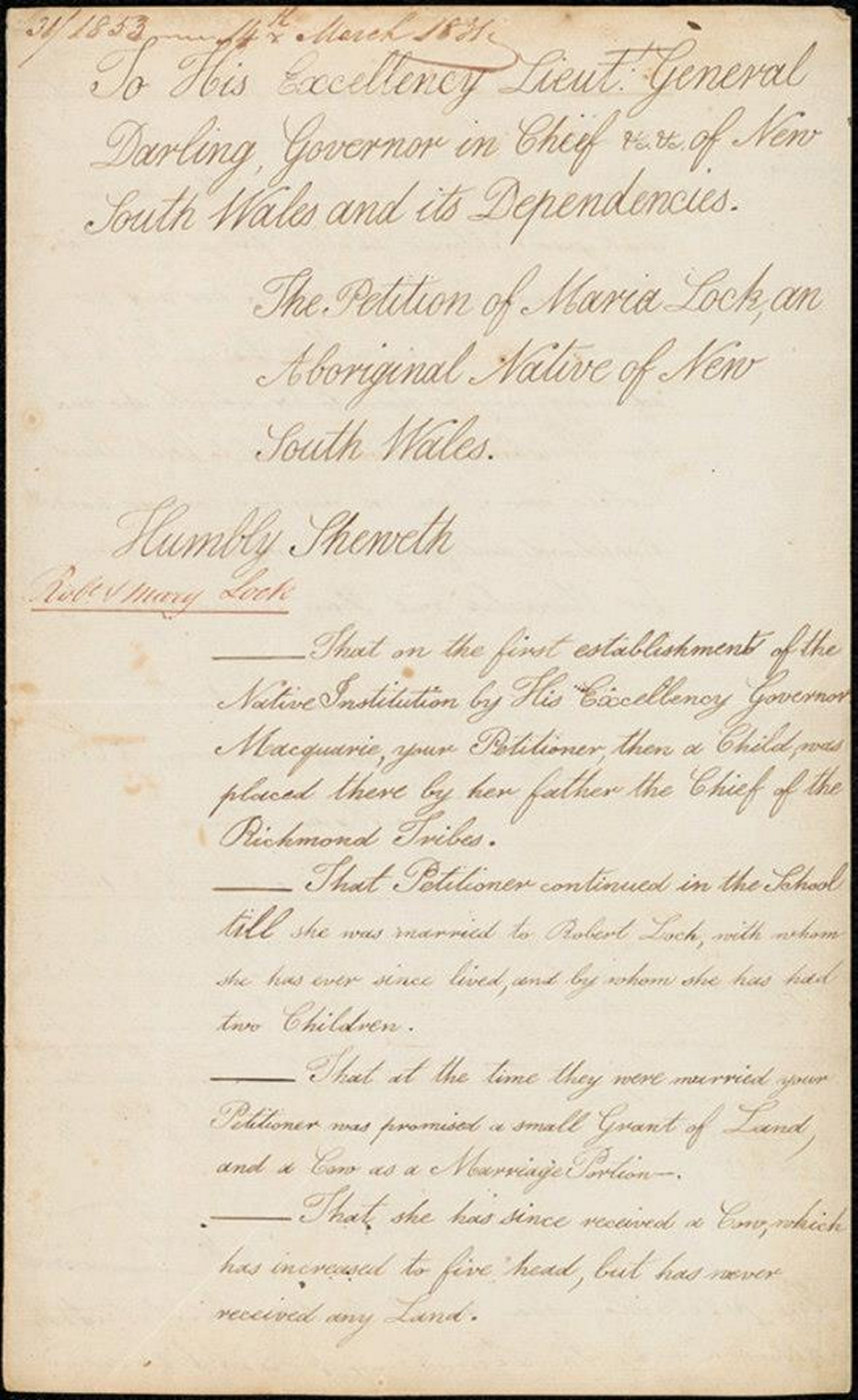

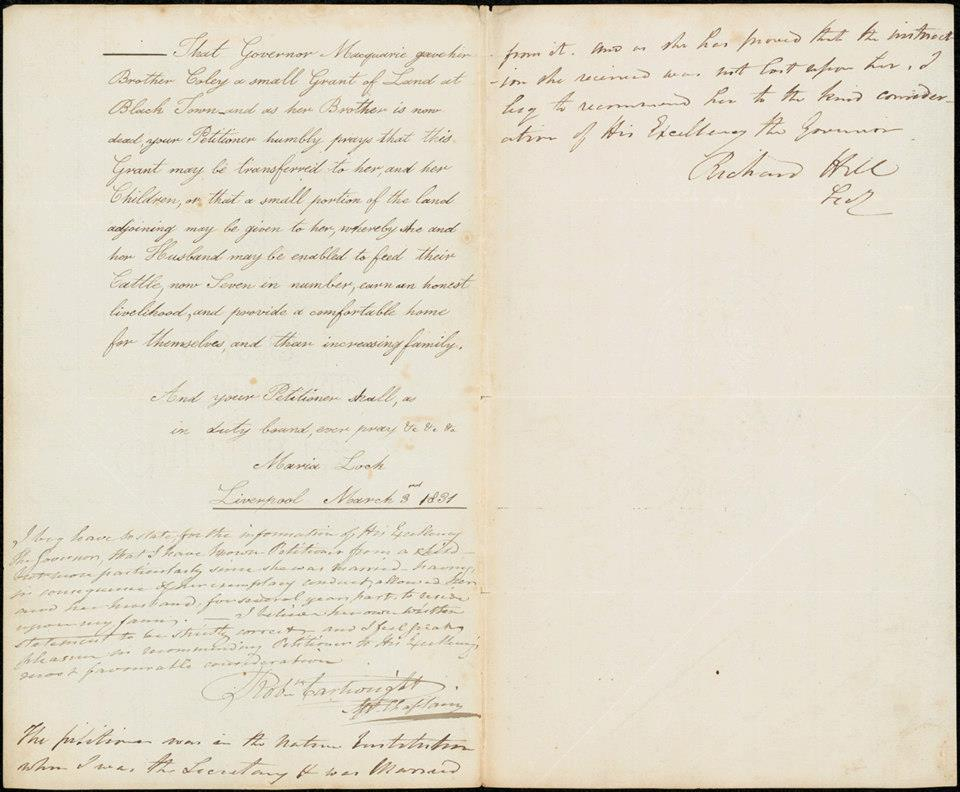

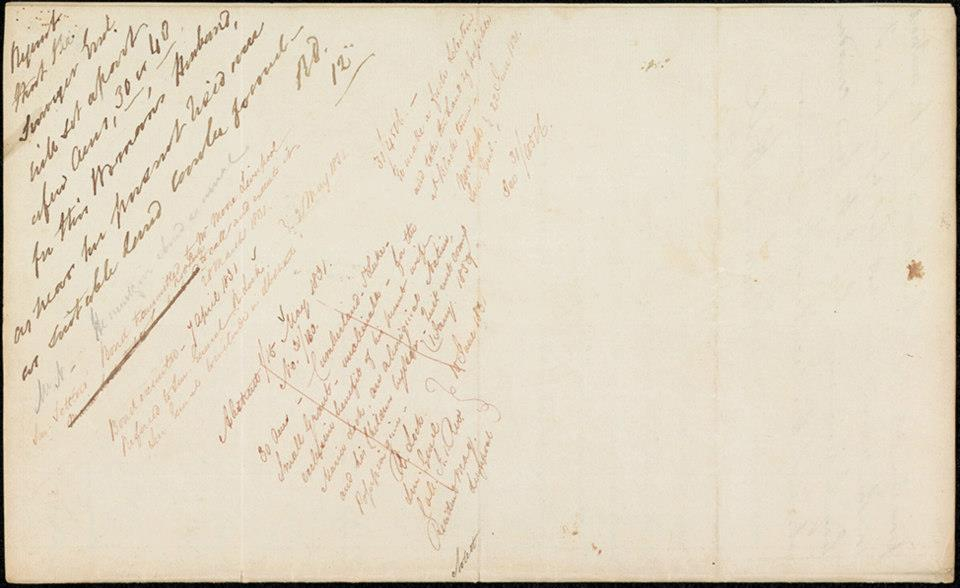

[media]The Native Institution's land was later acquired by Maria Lock, Colebee's sister [media]and a former prize-winning student at the Parramatta Native Institution. She had petitioned the government for her brother Colebee's neighbouring grant, [media]and for land at Liverpool, and left considerable land holdings to her children on her death in 1878. The Native Institution site remained in Aboriginal hands until the early twentieth century.

Land rights struggle

The Darug Tribal Corporation has long argued for the return of their land either as compensation under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 or as a result of traditional and continuous occupation under the Native Title Act 1993. Despite a documented record of land title and occupation on the Richmond Road 'Black Town' lands, the land has not been returned to Aboriginal people.

Darug Tribal Corporation elder, Sandra Lee, said in April 2013:

We want it back [the site of former Blacktown Native Institution] after waiting in vain for 20 years for the government's proposed Aboriginal cultural centre. [the site of the Black Town Native Institution]…is part of the ongoing history of Aboriginal people's struggle for land rights. It's time the site is celebrated within our broader community so that it receives the recognition it deserves'. [10]

References

Brook, J and Kohen KL. The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History. Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991.

Goodall, H. Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996.

Hinkson, M. Aboriginal Sydney: A Guide to Important Places of the Past and Present. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2001.

Karskens, G. The Colony: A History of Early Sydney. Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, 2009.

Morris, B. Domesticating Resistance: The Dhan-gadi Aborigines and the Australian State. Berg Publishing: Oxford, 1989.

Norman, H. 'What Do We Want? A Political History of Aboriginal Land Rights', Aboriginal Studies Press (2015).

Notes

[1] For further reading on Macquarie's legacy, the influence of Enlightenment thinking and the emerging administration of Aboriginal lives, see Heidi Norman, 'What Do We Want? A Political History of Aboriginal Land Rights', Aboriginal Studies Press (2015) 6; Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996); B Morris, Domesticating Resistance: The Dhan-gadi Aborigines and the Australian State (Berg Publishing: Oxford, 1989); Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2009)

[2] Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972 (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1996), 14

[3] 'First Aboriginal Feast Day at Parramatta 28 December 1814', Sydney Gazette, 31 December 1814, 2a online at The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive, http://www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema/1816/congress28dec1816.html, accessed March 8th 2015

[4] 'First Aboriginal Feast Day at Parramatta 28 December 1814', Sydney Gazette, 31 December 1814, 2d–3a online at The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive, http://www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema/1816/congress28dec1816.html, accessed March 8th 2015

[5] 'First Aboriginal Feast Day at Parramatta 28 December 1814', Sydney Gazette, 31 December 1814, 2b, online at The Lachlan & Elizabeth Macquarie Archive, http://www.lib.mq.edu.au/digital/lema/1816/congress28dec1816.html, accessed March 8th 2015

[6] J Brook and JL Kohen, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History, (Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991), 86

[7] J Brook and JL Kohen, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History, (Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991), 263

[8] J Brook and JL Kohen, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History, (Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991), 104

[9] J Brook and JL Kohen, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History, (Kensington: University of New South Wales Press, 1991), 179

[10] N Soon, 'It's time to give it back', Blacktown Sun, 29 April 2013

.