The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Ardill, George

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Ardill, George

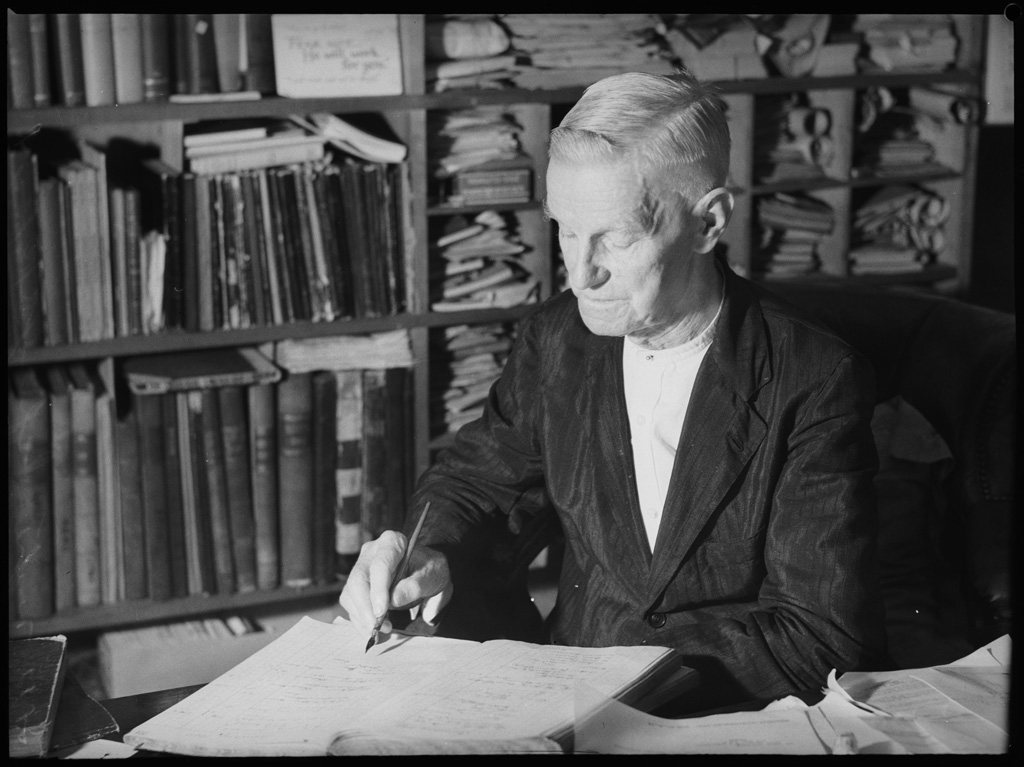

[media]George Edward Ardill, evangelist and social worker, was born at Parramatta on 17 December 1857 to Joshua Ardill, plasterer and Freemason, and his wife Anne Maria (née Johnson) and died on 11 May 1945 at Stanmore, Sydney.

After an elementary education and Bible training in the local Baptist church, he took an office job. In his mid-twenties, he briefly set up a stationery and printing business in Pitt Street, Sydney. He was a young man of strict principles, a teetotaller and a street preacher.

While in his twenties, he decided to devote himself full-time to organising charities and to evangelism. Attracted to the gospel temperance movement and with a gift for organisation, he formed the Blue Ribbon Gospel Army, a temperance organisation which remained under his direction for many years. Ardill also joined other temperance groups: the Local Option League on its formation in 1883 and later the New South Wales Alliance, serving it for 30 years as a councillor and sometimes as treasurer and secretary.

Women and children

At late-night street rallies taking the gospel to the godless of the alleyways and byways of Sydney, Ardill became aware of destitute and homeless women. Using his organisational abilities, he formed the Sydney Rescue Work Society in 1890, a major charity that financed his work with impoverished women. He approached wealthy philanthropists like the Methodist Ebenezer Vickery, a merchant who had premises in Pitt Street close to his own stationery business, and Samuel McCaughey, a pastoralist who gave generously to charities.

In 1884, Ardill founded an All-night Refuge and the Home of Hope for Friendless and Fallen Women, a lying-in hospital to which he attached a commercial laundry, where the inmates were employed and given training and a good dose of the gospel. The Crusade to Women was another he ran to reclaim homeless female alcoholics. In 1884–91, he organised two halfway homes for discharged prisoners.

Ardill turned his attention to children. In 1886, he founded the Society for Providing Homes for Neglected Children, which opened Our Babies Home that year, Our Children's Home at Liverpool in 1887 and Our Boys Farm Home at Camden in 1890, where older boys were given training on nearby farms. In the 1890s, Ardill organised crèches for working women.

By the 1890s, he was a director of 12 societies. He was moving gradually from rescuing the fallen to providing for the impoverished. He became less successful in extending his institutions despite persistence and some ingenuity in fund-raising. [1]

Heather Radi describes him as an energetic professional social worker and evangelist who loved to scheme and contrive in the interest of causes 'dear to his heart'. He was a mover-and-shaker and a Victorian public man, a moral improver who was absolutely certain of the validity of his notions. When he 'discovered' homeless women and abandoned children, he formulated the template that he would use to deal with impoverished Aboriginal children.

'Protecting' Aboriginal people

Ardill joined the Aborigines Protection Association which had been formed by the missioner Daniel Matthews in Sydney in 1878 as a committee to aid the Maloga Mission in southern New South Wales. The committee's work broadened to support the Warangesda Mission in the Riverina and secure further reserves, but it was ultimately a failure.

As secretary of the Association, Ardill was involved in the removal of the Maloga settlement to a site five kilometres downstream on the Murray at Cummeragunja, a 75-hectare reserve for Aborigines. Cummeragunja soon became a large New South Wales government reserve. Ardill was keen on the wholesale removal of people from other places.

In 1883, the Association lobbied the New South Wales government to replace its single Protector of Aborigines with a government-controlled Aborigines Protection Board, a goal which was achieved in the same year. In 1897, Ardill joined the Board as the Aborigines Protection Association's representative. He was energetic in visiting the rapidly growing number of Aboriginal stations and reserves across New South Wales, and in making several key recommendations to the Board, most of which were taken up.

He became the Board's most influential mover-and-shaker and was vice-president by 1909, when the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 was enacted, which gave the Board extensive powers of control over Aboriginal reserves and stations in the state. [2] Ardill often chaired meetings of the Board in the president's absence. On 30 November 1911, he was to make major changes 'for the better working of the Aborigines Protection Act in dealing with the Aboriginal population of the state'.

He recommended the appointments of an Inspector of Aboriginal reserves and stations, and of a 'Home Finder' and Superintendent of Apprentices, establishment of residential training homes for Aboriginal girls and Aboriginal boys, and the amendment of the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 to secure more comprehensive powers of control over Aboriginal children and define clearly the power to apprentice such children. He went on to suggest that small reserves be closed and the people settled on larger reserves under appointed government managers, and that 'able-bodied quadroons and half-castes' be removed from the Board's reserves after a period of 12 months. [3]

Ardill advocated a rigid carceral, or prison-like, universe for all Aboriginal adults who were unfortunate enough to be living in the state's Aboriginal reserves and stations. His suggestions at the Board's regular meetings in Phillip Street in Sydney substantially aided the creation of the Stolen Generations of the twentieth century in New South Wales. On a single day, he turned the Aborigines Protection Board into a ministry of fear. Most of his suggestions became policy as expressed in the Act's Amendments, until the establishment of the Aborigines Welfare Board in 1940. Even then, things did not improve very much. The deep shadow of Ardill's ideas remained.

His policies had a profound effect on Aboriginal station children. Their enforced occupational destinies were to be either farm labourers or domestic servants. The Syllabus for Aboriginal Schools issued in 1916 by the New South Wales Department of Education pointed them in those directions, with an emphasis on practical work such as gardening, needlework, manual work (for boys) and laundry work (for girls). The sole object of the syllabus was to assist boys to become capable farm and station labourers, and the girls, useful domestic servants. [4]

In 1954, a Sydney newspaper presented a case study that vividly demonstrates the long-term impact of Ardill's suggestions made in 1911:

Everybody will hope, with the release of Betty Zooch from the reformatory to which she was condemned, that happier days are dawning for this little Aboriginal orphan... Now 16 years old, she has been a ward of the Aborigines' Welfare Board [and formerly the Protection Board] ever since she was a baby.

Sent out to work among strangers, she committed the crime of being lonely and homesick. She also stole 10/- and a bit of tobacco.

For these sins, she was sentenced to be confined for up to 2 years in a penal 'training school' hundreds of miles from the only people she knew as friends... [5]

The newspaper went on to emphasise that even though Betty was then allowed to live in a home where she would be given sympathy and understanding, its readers would be justified in wondering whether it was an isolated case, implying that it was not. Even Betty's future was bleak, as she had no other means of supporting herself other than being a domestic servant.

In 1911, the year Ardill made his suggestions in the Board's meeting, two of his recommendations were achieved. The Cootamundra Training Home for Girls was founded in an old hospital acquired by the Board. A matron, Emmaline Rutter, was appointed for the Home. A 'Home Finder', Alice Lowe, was also appointed. Her responsibility was to make enquiries about suitable homes for female Aboriginal apprentices. As well, she was to inspect such apprentices in their appointed situations. Kinchela Training Home for Aboriginal Boys, near Kempsey, was founded in 1924, following the model that Ardill had set up in farm training.

While Ardill had become the Board's policy-maker between 1911 and 1915 when the Act was amended, his triumph was short-lived. He resigned from the Board in April 1916 and two months later the Board was reconstituted and dominated by high-level public servants. [6] It was the beginning of the end for the days of the power of rigid Victorian philanthropists.

Ardill's 1915 amendments did not pass through the New South Wales Parliament without some debate. The member for Murrumbidgee posed the question of whether the amendments amounted to 'stealing the child away from his parents'. The reply from the conservative side was that it was not a question of stealing the children away but of saving them. [7] The nineteenth-century notion of child-saving by removal from environmental influences to an institution or boarding out as a servant still had resonance in society.

George Ardill overreached himself with the 1915 amendments, and was condemned in some religious circles, such as the Australian Aborigines Mission, for attacking Aboriginal family life and even the reintroduction of slavery. [8] It was, however, worse than what had gone before in the nineteenth century, and the Board's power over Aboriginal children was to remain for decades.

Ardill was not alone in having a profound effect in promoting the dispersal and dispossession policies of the Aborigines Protection Board between 1897 and 1940.

In 1934, George Ardill was awarded an MBE for services to the community. He was buried in Waverley Cemetery in 1945.

George Ardill junior

George Ardill's son, also George Edward (1889–1964), grew up in the family at Stanmore, Sydney, and absorbed many of his father's interests, but unlike his father, who was a Sydney man of public affairs, Ardill (jnr) became absorbed into the country way of life. At first he farmed at Coraki and then at Gunning where he bought a dairy farm. In 1921 he established himself as a local country auctioneer and agent. A prominent Methodist lay preacher, he also served on the Gunning Shire Council in the 1920s and 1930s.

George Ardill (jnr) turned to state politics and was elected in the Yass seat as a Nationalist Member of the Legislative Assembly. He found his way onto the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board on 12 November 1935 and served on it during its last troubled years. Like his father before him, he was active on the Board, raising issues in an energetic manner, although his approach appeared to be less hardened than his father's. In early 1938, he advocated the need for employment opportunities for Aboriginal youths:

It was resolved that steps should be taken in suitable cases [to] find employment in the Police service for young able-bodied Aborigines who would be trained in the handling of horses, looking after motor vehicles, and to be found employment on sheep stations and farms, their places in the service being filled by other Aboriginal recruits with similar ends in view. [9]

Thus George Ardill (jnr) wanted a scheme by which Aborigines were trained in the police force and then placed out on sheep stations with these skills available for grazier employers. The police chief was instructed to keep this matter in mind.

References

Minutes and Annual Reports of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board, 1883–1940

Heather Radi, 'Ardill, George Edward (1857–1945)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 7, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979, pp 90–92

Victoria K Haskins, One Bright Spot, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, 2005

John Maynard, Fight for Liberty and Freedom: the origins of Australian Aboriginal activism, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2007

John Ramsland, The Rainbow Beach Man: the life and times of Les Ridgeway, Worimi elder, Brolga Publishing, Melbourne, 2009

John Ramsland, 'The Aboriginal Training Home, Kinchela 1924–1965', Journal of Educational Administration and History, vol 38, no 3, December 2006, pp 237–48

John Ramsland, 'The Aboriginal School at Purfleet, 1903–1965', History of Education Review, vol 35, no 1, 2006, pp 47–57

John Ramsland, ' "The Great Australian Silence Reigns": Aboriginal children and schooling in New South Wales', Annual National Museum of Education Lecture, 23 September 2009

Leonard Fox, 'Aborigines in New South Wales', unpublished typescript, February 1960, Mitchell Library

Notes

[1] Heather Radi, 'Ardill, George Edward (1857–1945)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 7, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979, pp 90–92

[2] John Ramsland, '"The Great Silence Reigns". Aboriginal children and schooling in New South Wales 1901–1909', Australian National Museum of Education Annual Lecture, 23 November 2009, pp 7–8

[3] Minutes for 30 November 1911, Aborigines Protection Board Minute Book, 9 March 1911 – 21 December 1911, State Records New South Wales, 4/7117

[4] Course of Instruction for Aboriginal Schools, issued 1916, Government Printer, Sydney, 1919, pp 1–9

[5] Editorial, Sydney Sun, 2 November 1954

[6] Victoria K Haskins, One Bright Spot, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, 2005, pp 30–1

[7] John Maynard, Fight for Liberty and Freedom. The origins of Australian Aboriginal Activism, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2007, pp 37–8

[8] Heather Radi, 'Ardill, George Edward (1857–1945)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 7, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1979, p 91

[9] Minutes of the Aborigines Protection Board, 2 February 1938, microfilm, State Records New South Wales

.