The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The decorated footpath

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The decorated footpath

Paved footpaths are a familiar feature of our urban environment. Whether taking a purposeful walk, a social stroll, or a healthy jog, we expect the footpath to be there, providing a safe and sturdy platform beneath our feet. But pavements should not be dismissed as simply utilitarian. A close inspection of Sydney footpaths will reveal that they are seldom purely practical, and never plain. There is always some decorative embellishment embedded in the paving or applied to its surface.

Pride and ostentation

Footpaths [media]are a matter of civic pride. The state of the sidewalks is an indicator of a city's wealth and progress. It shows how well (or how poorly) a city looks after its citizens and visitors. That is why, in the lead-up to the 2000 Olympic Games, the dowdy asphalt on the major pedestrian routes of Sydney's central business district was torn up and replaced by smart, geometrically arranged bluestone flagging. Months of chaos for pedestrians and business owners resulted in a sparkling facelift for the influx of Olympic visitors to admire. Chic new suburban developments and civic improvements in older centres have followed suit, with pedestrian thoroughfares finished in granite pavers or their synthetic equivalent.

Footpaths [media]were considered so important in the early days of the colony that many of them were paved long before the carriageways were surfaced. Wooden 'foot crossings' were even constructed across streets to save 'foot passengers' from having to pick their way through horse manure and dust or mud as they crossed from one side to the other. Terminology changes over time: what Sydneysiders now call the footpaths or pavements have often been called footways (and sometimes even sidewalks). Pedestrians were known as foot passengers until the early 1900s.

City footways were essentially an extension of the indoors. They functioned as a 'welcome mat' for customers and, before the advent of plate-glass windows, a place where store owners could display their wares. Although Sydney Council installed kerbs and gutters, owners of new buildings were obliged to pave the footway outside their premises, or pay the Council to do it. Flagging was the usual method, the flagstones often coming to Sydney as ballast on ships from overseas.

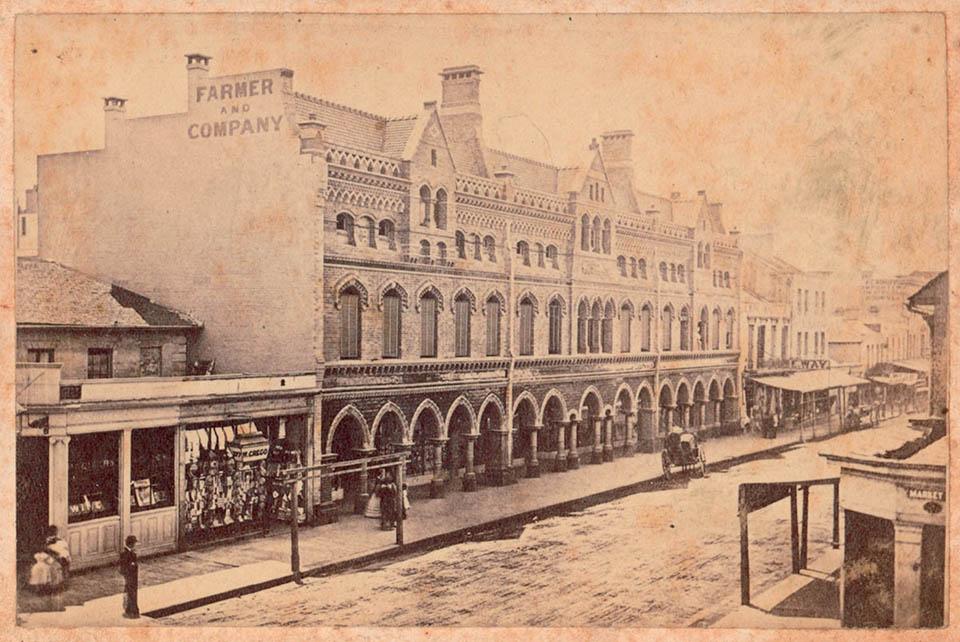

For [media]city businesses, the appearance of the adjacent paving was as important as its utility. In 1873, prominent architect J Horbury Hunt wrote to the Lord Mayor James Merriman with a request about the laying of kerb and guttering in front of Messrs Farmer and Company's new premises. As he explained:

This firm is going to a very great expense to make these new buildings an ornament to this end of Pitt St. … the most important feature in the design … is an Arcade extending the whole length of their premises [with] flagging – which is to be the very best of "Blue stone" from Melbourne. Therefore to make the design complete we ask you to put down kerb and gutters of same material … and so help to furnish a fine block of buildings. [1]

By [media]the late 1800s the flagstones of Sydney were being replaced by new materials, usually versions of asphalt and later, concrete. Paving stones might have a certain charm, but their cracked and uneven surfaces were expensive to maintain and a hazard for pedestrians. Smooth asphalt surfaces were considered to be modern and progressive.

As the outskirts of the city grew into suburbs, and farmlands were marked out into streets, local governments also chose to pave the footways with asphalt. A description of the wealthy borough of Petersham in 1890 noted

… at the present rate of progress, it will not be many years before the Council can boast that every street is metalled and every footpath asphalted. When this can be said there will be no pleasanter abiding place around Sydney than Petersham. [2]

The written word

Not [media]only do the state of footpaths and the materials they are made of carry an implied message, but their flat surfaces can also function as a canvas for written messages. When concrete replaced asphalt in suburbs like Petersham in the mid-twentieth century, a touch of class was added by setting street names into the pavement in contrasting coloured cement. Many of these red-coloured names remain, although some are rather the worse for wear. Much more recent pavement improvements in some parts of Sydney, such as Darlinghurst, also incorporate street names, but nowadays these are neatly engraved in the concrete.

The very first signs embedded in Sydney pavements were not street names but the names of adjacent businesses. For example, in 1884 the owners of a company in George Street asked Sydney Council for permission to construct the words Market Chambers, in brass or marble, flush with the flagging of the footpath outside their premises. Permission was given, on the grounds that similar requests from other companies had already been granted. [3]

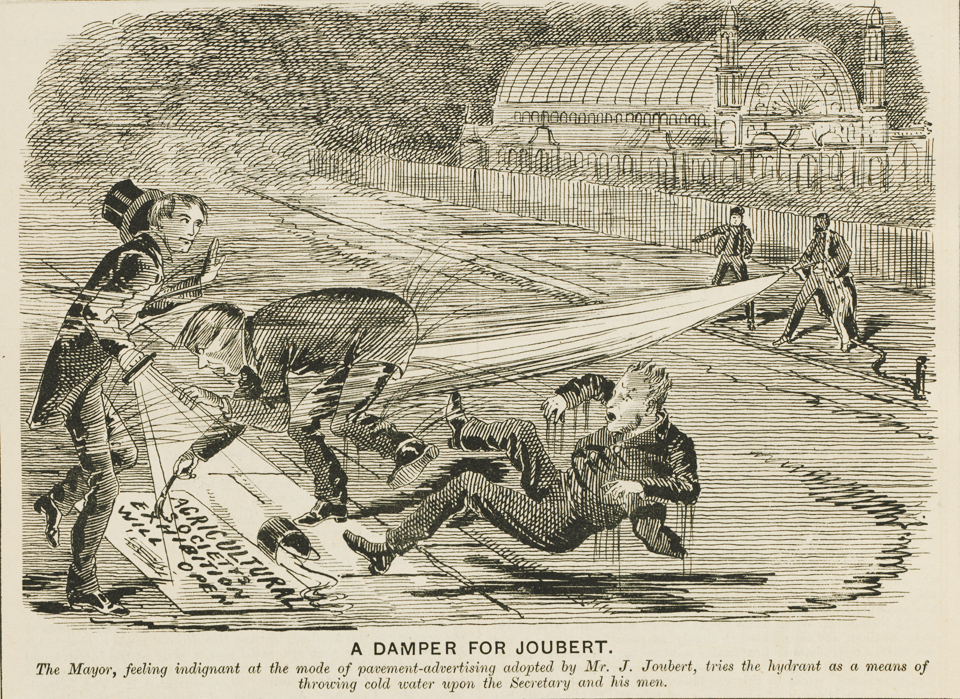

When the [media]new paving technologies were introduced in the late 1800s, opportunities for broadcasting written messages on the pavement expanded. Asphalt turned the footpaths into giant blackboards where small business people quickly seized the chance to advertise. This was too much for one Surry Hills citizen, who wrote to the Town Clerk in 1904 to complain:

Coming into town this morning I find that the footpaths of Crown and Oxford Streets are daubed with a white-wash advertisement of “Joe Gardiner's boots”. On the asphalt at the Oxford St entrance to Hyde Park the advertisement covers almost all the available space, and the appearance of the place is anything but aesthetic. [4]

Painting on the pavement was illegal, but only perpetrators caught in the act could be prosecuted. And indeed, at the Town Clerk's request, police increased their night-time vigilance and two offenders were soon nabbed.

Despite being illegal, the practice of advertising on the footpaths continues to this day, perhaps not in lime whitewash but often in chalk. It is not unusual to see chalk notices for café specials, or 'arrow trails' to garage sales. In 2008–10, a 'chalk battle' was waged between the owners of shops in the side-streets of Newtown, each of them regularly renewing their chalked signs on the main shopping strip and at busy nodes in nearby neighbourhoods.

Preaching and politicking

Repetition [media]is an important part of most advertising campaigns. It was the technique of Sydney's most famous chalk graffitist, the 'Eternity Man'. His message is not generally thought of as an advertisement – but of course it was. Arthur Stace was a former no-hoper who had been dramatically converted to Christianity in the early 1930s. After a miraculous epiphany in 1932 he began walking the city's streets in the early hours of the morning, inscribing the word 'Eternity' in copperplate script on the footpaths over and over again. Sydney's enduring fascination with this chalked advertisement for an afterlife with God was fuelled by the mystery over where these signs had come from. Arthur Stace's identity was not revealed until he had been writing his message for over 20 years.

Chalk continues to be the medium of choice for many people with a message to preach: gays proclaim their pride, student collectives denounce capitalism, and street-proud residents admonish 'filthy dog owners'. Unless these inscriptions are small and nestled at the edge of the pavement – as Arthur Stace's were – they do not last long but are soon scuffed by passing feet. Chalking is labour-intensive, but it inspires spontaneity, and its ephemeral nature leads graffitists to believe that it is not illegal.

Advertising

In fact, graffiti of any [media]sort is illegal in New South Wales – defacing by chalk, paint, felt-tip markers or other media is an offence, although some municipalities, including the City of Sydney, take the view that rapid removal is a better deterrent than fines. Nevertheless, advertisers and activists, wielding all sorts of marking devices, still choose to flout the rules and risk rapid erasure. Perhaps they feel their notices are safe from the pavement scrubbing machines, because there are also many official survey marks on the footpaths, sprayed there in fluoro colours by councils and utility companies.

Towards [media]the end of the 1990s, little spray-painted stencils began to appear on Sydney footpaths. Some of these were made by activists broadcasting their political slogans, while other, more esoteric messages were about dance parties, raves and garage bands. This type of promotion has sometimes been complemented by a wider advertising campaign in free entertainment newspapers, on stickers attached to traffic light buttons, or on fliers pasted to municipal litter bins.

[media]Commercial companies, targeting young urban types, soon copied the idea in legally questionable stencil advertising campaigns. The green 'X' of Microsoft Xbox marked the spot around Sydney streets in 2001 when this product was first released. Many others have followed, and the pavements of busy clubbing districts, such as those in Oxford and Crown streets, are favourite locations for stencil advertisers.

It was also in the 1990s that it became important for businesses and other organisations to have a presence on the World Wide Web, and since then pavement stencils have often been used to publicise an organisation's website. Marrickville Council, in Sydney's inner west, was a fairly early enthusiast, stencilling its new web address on footpaths around the municipality in 2002. More recently, an alcohol company drew people into a viral advertising campaign via large fake 'proposed bikestand' sites stencilled at inconvenient places on city footpaths in 2008.

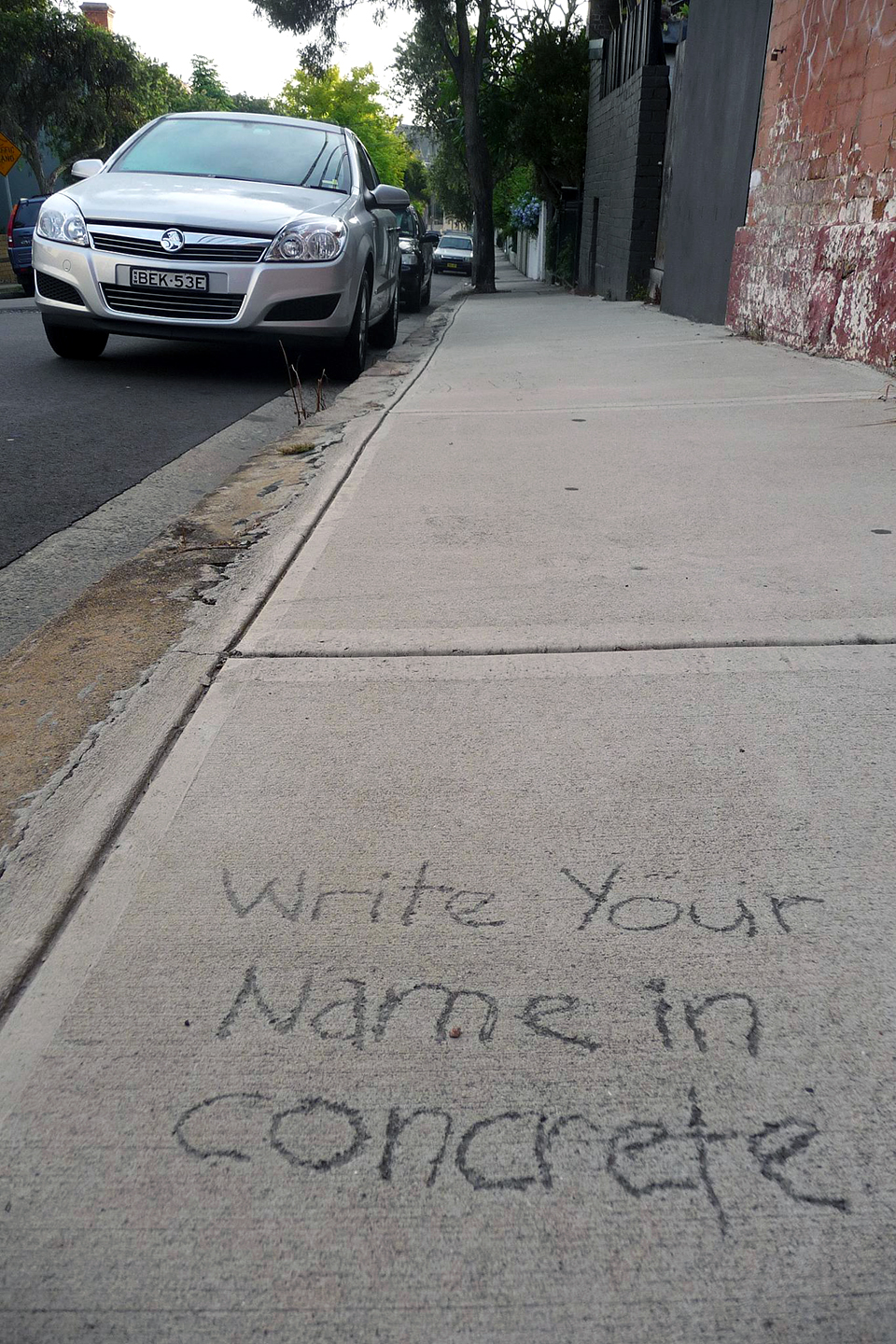

[media]But it is not only goods and services that are advertised on the pavement. Sometimes people just feel like publicising themselves, their personal allegiances or their romantic inclinations. Wet cement has long been a favourite medium for this kind of message and in between the initials and names it is possible to read a great deal in the concrete about a neighbourhood or locality – who used to love who, who was proud of being Aboriginal, what politicians were hated, and what was the local recreational drug of choice.

Crowd control

At [media]busy times in the central business district, there is no chance to linger over the making or the reading of pavement inscriptions. In fact, pedestrians in a hurry maintain that others should not linger over anything at all. Since the 1870s, letter writers and newspaper columnists have fumed over window shoppers and social chatterers blocking the footpath, and have likened city crowds to [media]flocks of sheep going in different directions or cattle caught in a barn. [5] From time to time, the solution has been for traffic authorities to paint lines on the pavement to assist in herding pedestrians and corralling bus queuers. A centre line has appeared and disappeared on footpaths over the decades, sometimes accompanied by a stencil that warned 'Keep left'. The last time the centre line was applied in George Street seems to have been the 1980s. During periods when it has been absent, letter writers have waxed nostalgic over its regulatory powers. In 1974, for instance, a citizen from Belfield wrote to the Lord Mayor:

Please bring back the “YELLOW LINE” that adorned Sydney City footpaths a decade ago, so that at least the poor employees in the city area (like myself) get a bit of a “fair go” at all times. [6]

Amusement and art

Though [media]many of the adornments on the footpaths are about regulation, marketing, proselytising and self-promotion, there is still some room for fun. Children have always used the pavement for games – stepping over the cracks to avoid being eaten by bears, marking out hopscotch squares and marble circles with chalks or bits of fibro, and drawing extravagantly coloured crayon pictures. Now there are adults who are joining in as well. In the back streets of Enmore there is a decorative hopscotch and the woman who painted it likes to watch through her window as people have a bit of a hop and jump as they pass by.

Written [media]jokes are part of the fun, some impetuously inscribed in wet cement or spilt paint, some premeditated and applied by stencil, some scrawled in chalk. But the cheekiest jokes are those that subvert the official signs on the pavement.

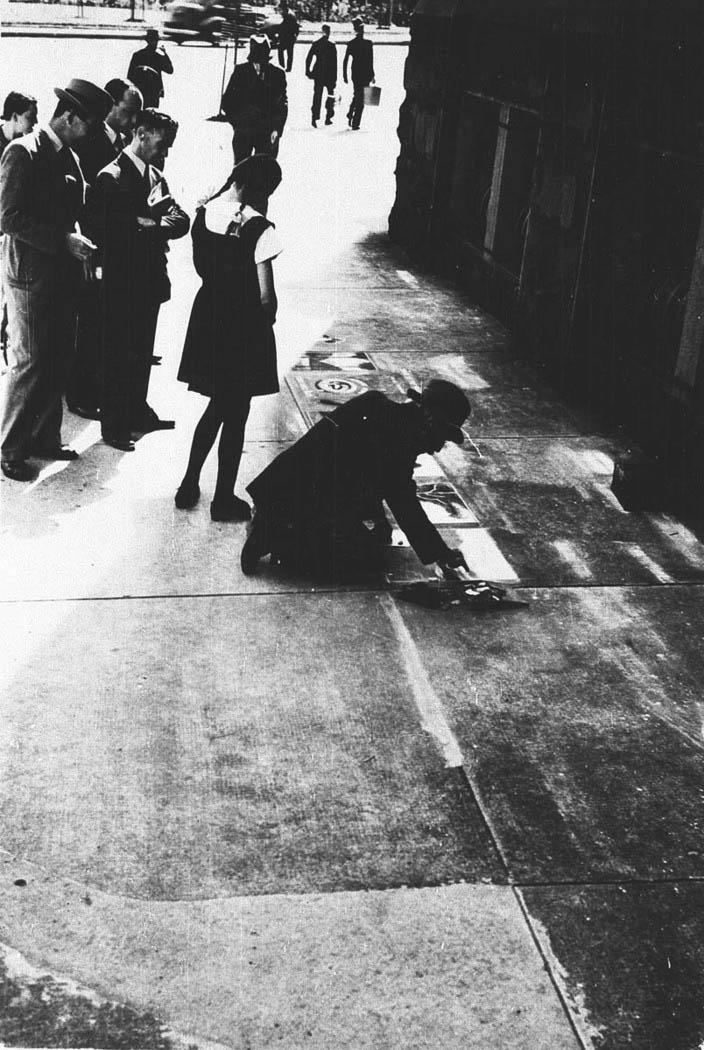

The footpath is a gallery of horizontal art works as well. In Sydney, pavement artists in the nineteenth and the mid-twentieth centuries eked out a living making chalk drawings on flagstones or asphalt. These men were often returned servicemen. In recent times buskers have generally not been allowed to draw directly on the pavement but sometimes street beggars manage to make a small artistic gesture in return for coins. There is also the annual Chalk Urban Art Festival in Darling Harbour, where the most skilled of the participating artists use elaborate techniques to produce surprising three-dimensional works.

Less showy, [media]but perhaps more impressive and certainly more permanent, are the commissioned plaques and public artworks embedded in the city's pavements. Demonstrating once again the symbolic role of footways in presenting the city's image, many of Sydney's pavement installations were integrated into the civic improvements that preceded the 2000 Olympic Games. Ironically, in marking historic sites and past events, such works often commemorate what the paving itself has interred. 'Into the head of the cove' marks the course of the Tank Stream, now a drain underneath Pitt Street Mall; a curve of contrasting coloured paving stones and metal plugs at Circular Quay indicates where the edge of the original shoreline was before the area was reclaimed and paved; 'Wuganmagulya' at Farm Cove recalls former Aboriginal inhabitants and their long-since-obliterated rock carvings.

However, site-specific art [media]need not be elegiac. There are stealthy artists around the city whose ephemeral footpath works celebrate not the dead and gone, but the here and now – the shadows of everyday street furniture cast by street lights, night-time shenanigans in parks, or the election of a US President. It is pavement creations like these that capture the zeitgeist.

What a world there is to be explored in the decorations on the footpaths!

Notes

[1] City of Sydney Archives 26/123/930 (1873)

[2] Allan M Shepherd, The story of Petersham 1793-1948, The Council of the Municipality of Petersham, Sydney, 1948, p 25

[3] City of Sydney Archives 26/195/148 (1884)

[4] City of Sydney Archives 1904/0592 (1904)

[5] See, for instance, City of Sydney Archives 26/121/511 (1873); 1902/0068 (1902); 1083/16/115 (1913); 1083/18/132 (1914); 268/60 (1960–1978)

[6] City of Sydney Archives 268/60 (1960–1978)