The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Health and welfare

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Health and welfare

The 1786 Heads of a Plan proposal for a colony at Botany Bay sought to create a settlement that would 'be fully sufficient' for the 'maintenance and support' of colonists and authorised the appointment of surgeons who would 'attend to the wants of the sick'. [1] So instructed, Governor Phillip arrived in Sydney with the health and welfare of colonists an uppermost concern. Nonetheless, while the Eora peoples of the Sydney harbour region found food plentiful, the colonists struggled to survive in this alien environment.

The early years were harsh; crops failed, supply ships were delayed and drought frustrated efforts to provide the necessities of life. In these 'hungry years' the governor rationed government stores to feed and clothe convicts and other colonists in need. Health was also a priority; able-bodied colonists were needed to sustain the settlement. In the first months Phillip built a tent hospital in what is now The Rocks. In 1792 a brick hospital was built at Parramatta and the Rum Hospital in Macquarie Street (later Sydney Hospital) was opened in 1811. In the same year the first lunatic asylum was established at Castle Hill. [2] Government provision of health and welfare services was a central task from the very beginning of Sydney's colonisation and has remained so since.

Joint responsibility

Within a few decades, however, health and welfare was no longer merely a matter of government effort but also a responsibility of the wealthy. After initial hardship the colony became increasingly prosperous, a place where men of relatively humble origins possessed of initiative and enterprise might reach a level of comfort unattainable at home. A landowner, merchant and commercial class emerged and it was to this class that the government turned to ensure growth and prosperity. Governors still supported some convicts on the public purse but by 1810 two-thirds were assigned to landowners who took responsibility for their upkeep. In time substantial numbers of colonists were free settlers, attracted by the opportunities offered by colonial expansion. Many emancipated convicts preferred to stay than return. By 1828 there were 36,000 colonists in New South Wales, the majority in the Sydney region, around a third of whom were convicts. [3]

In any burgeoning colony there were bound to be winners and losers. [media]While well-off colonists ensured their own welfare and paid for medical services, other colonists found themselves unable to survive without assistance; the unemployed, drunken, sick, ill, orphaned, widowed, insane, and aged and infirm. How were these 'unfortunates' to be supported? The answer to this question rested on English precedent and tradition, modified and adapted to the peculiar circumstances of colonial society. [4]

English charity and the 'poor law'

Charity was a traditional Christian virtue and all churches supported parishioners suffering misfortune and reached out to other flocks (even 'heathens') with benevolence, tinged with moral fervour and missionary zeal, to bring them into the fold. Similarly, wealthy citizens demonstrated their virtue through philanthropy. The other great English welfare tradition was the 'poor law', originating in the fourteenth century, whereby poor law overseers levied rates on landowners to establish relief funds that would support local parishioners. The poor would normally only receive support from their own parish of settlement and those seeking assistance from outside were refused. [5] While the poor law system was easily adopted in Britain's American colonies, it was far from suitable for New South Wales where settlement was sparse and dispersed. Few parishes had sufficient landowners to sustain an adequate poor rate and in far-flung districts overburdened police and magistrates already had many other administrative duties to perform. Thus in Australia poor relief fell more heavily on colonial administrations. What principles guided this government provision?

The early years of colonial settlement in New South Wales coincided with a time of momentous change in the English poor law system. Since its inception the poor law had been designed to discourage indigence by making relief local. By the late eighteenth century the effort to contain poverty in local areas, however, was collapsing under the weight of extensive land enclosures, increasing commercialisation of agriculture, the growth of mercantile and industrial enterprises and the emergence of large towns and cities. The labouring poor had to travel in search of work and when misfortune struck they were often far from their place of birth. Moreover by the late eighteenth century a series of poor harvests, a significant increase in the population, large numbers of soldiers and sailors returning from the wars with France, the emergence of organisations of labouring poor and complaints from poor law commissioners about the problems they faced controlling the swelling numbers of relief seekers created the conditions for an intense debate about how best to curb the problem of poverty.

On one side of the debate were poor law commissioners, some dissenting clergy, organisations sympathetic to the plight of soldiers and sailors, and radicals who all saw poverty as a natural consequence of fluctuations in the market for labour and food. In 1795 such groups supported the new Speenhamland poor law regulations, which waived the requirements for local assistance and eased the workhouse test to alleviate the plight of the poor. Such groups accepted that much poverty arose from famine and starvation wages and was not the fault of individual families.

On the other side were political economists, evangelical reformers, business and commercial interests, Tory and Whig politicians, and philanthropists who saw poverty as largely a moral failing in the poor. They demanded stricter rules governing the provision of assistance to ensure that only the genuinely impoverished were helped and the rest forced to return to the labour market to earn a living through honest toil. These more punitive attitudes to the poor slowly gained the upper hand and were entrenched in the new poor law of 1834, which stiffened the workhouse test and made assistance more difficult to obtain. [6]

The new poor law ethos had a profound influence on the provision of assistance in New South Wales. Churches, charities and governments trumpeted the importance of differentiating between the deserving and the undeserving poor in the granting of relief. The deserving were those whose misfortune arose from circumstances beyond their control – the aged and infirm, sick and injured, orphaned and neglected children, widows and the insane. The undeserving were those whose poverty was believed to be a consequence of idleness, depravity and lack of moral rectitude – the unemployed, drunks, members of the criminal and 'depraved' classes, and those who demonstrated little interest codes of respectability. Such people should be denied assistance in order to force them to adopt habits of industry, temperance and thrift. [7]

Philanthropy in the colony

These principles and practices shaped colonial philanthropy. As the colony grew in size and complexity there was an increasing need to assist the impoverished and unfortunate who had no immediate call on the government commissariat. In 1801 the wife of the colony's third governor, Anna King, Richard Johnson, the first colony's Anglican chaplain and Samuel Marsden, established an asylum to rescue the many young girls 'verging on the brink of ruin and prostitution'. [8] There, wayward and orphaned girls were housed, fed, trained in the domestic arts and given instruction in religion and morality. Aboriginal children were also a priority. In 1814 Governor Macquarie established a school for Indigenous children, the Native Institution near Parramatta and later Blacktown. [9]

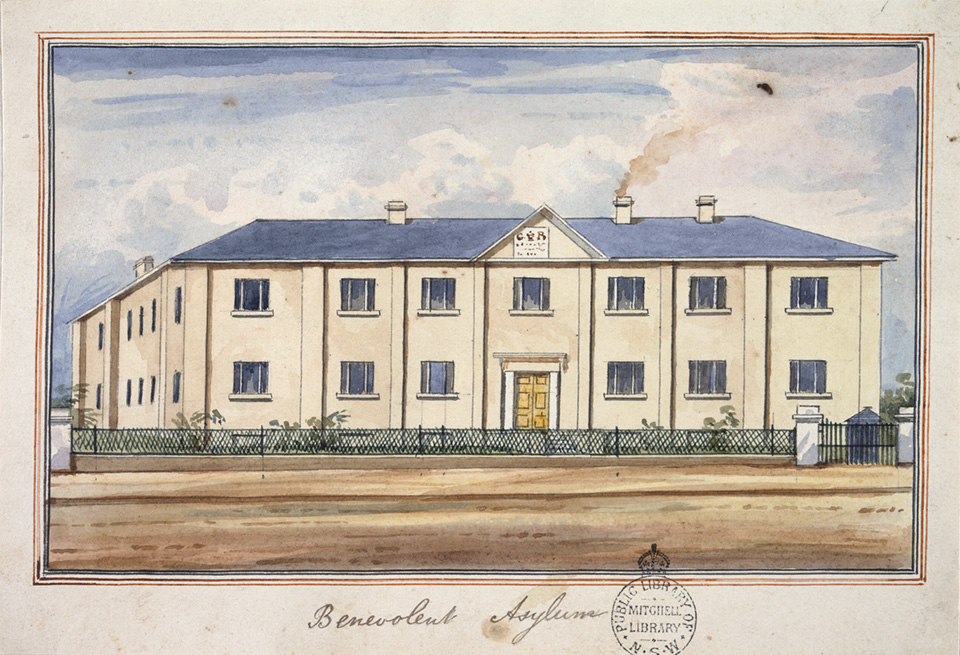

[media]By the early years of Macquarie's term as governor, Sydney had a hospital, an insane asylum and schools for orphans and natives. But the health and welfare needs of colonists were increasing, creating the imperative to institute a more comprehensive charity network. In 1813 a small group of evangelical colonists established the New South Wales Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Benevolence, seeking to promote missionary work and charity. Charity, however, consumed much of their energies and within five years the society had distributed poor relief to over 600 colonists. In 1818 it changed its name to the Benevolent Society of New South Wales, becoming the largest and most significant charity organisation in New South Wales, remaining so to this day. It assisted such diverse groups as the aged and infirm, destitute families, fallen women, nursing mothers and the unemployed. In 1821 the society built an imposing asylum (expanded and extended many times) on the site of what would later be Central Railway Station: a memorable symbol of private benevolence and the heart of poor relief in Sydney until its demolition in the first years of the twentieth century. [10]

Government and charity

Nonetheless philanthropy and poor relief faced major challenges in nineteenth-century Sydney. The proportion of wealthy citizens was small, and many of those who made substantial fortunes were self-made men more inclined to safeguard their fortune than distribute some of it to the less well off. Few were inclined to support charities by paying a charity organisation subscription. [media]Even in the 1860s the Secretary of the Benevolent Society was still complaining about the fact that 'so few people are subscribers and the same people subscribe to them all'. [11] Thus all charities faced a major hurdle in finding sufficient support. As a consequence, governors, and later the New South Wales Parliament, had to vote considerable funds each year to support both government asylums and private charities.

Government involvement posed a major dilemma for philanthropists. On the one hand they were dependent on the government for much of their funding. On the other government involvement threatened to convey the idea that fortunate colonists need not bother becoming subscribers. Worse, for the less fortunate it might cultivate a belief that relief was a right rather than a gift, undermining the moral reform imperative that was at the heart of the charity ideal. As Governor Darling explained in 1828, if the government became more involved 'inhabitants…would no longer subscribe at all' and it 'would induce a greater number of the poor to seek support…instead of restraining them'. [12] Similarly churches feared that government involvement would break the pastoral link with their flock. It might encourage people to pick and choose a church or leave altogether in pursuit of more generous relief.

Thus governments, churches and charity organisations struck a peculiar colonial arrangement. Governments assumed responsibility for some populations, notably lunatics, for whom there was little philanthropic support. More commonly, however, governments provided much of the funding for colonial charities and some support for church charity institutions. In return government officials had the power to recommend particular colonists for relief. But the funds provided were always insufficient to the needs of organisations, leaving a gap to be made up by private subscription and donation. More importantly the administration of relief was left in the hands of philanthropists and churches.

Why was private benevolence seen as so important? Philanthropists and governments, influenced by early nineteenth century English poor law reformers, feared that if charity were readily available, then many would opt for dependence rather than work. To guard against the perils of dependence required vigilance and strict application of charity principles. Two strategies were seen as essential in this regard. First assistance should always be less than what might be obtained by the lowest paid worker, a concept that scholars have termed 'less eligibility'. [13] In other words work should always be a more attractive proposition than dependence and it should be clear to all charity recipients that if they were able to work they would be better off than if they remained dependent. The second was that philanthropists needed to ensure that 'unscrupulous idlers', impostors perfectly capable of earning a livelihood but too indolent, dissolute or criminal, should be denied assistance.

Detecting 'unscrupulous idlers'

The challenge was how to detect and prevent imposture. In this context philanthropists stressed the importance of a direct and personal acquaintance with the poor. Philanthropists needed to know each recipient, understand their circumstances and regularly check to ensure that their circumstances had not changed such that they should be taken off the charity roll. While philanthropists might have an understanding of the lives of the poor in their vicinity a personal acquaintance with all those seeking relief was rarely possible. Thus charities developed three main techniques to safeguard against imposture.

The first was a recommendation. No person could receive relief unless they had a recommendation from a subscriber to a charity. In other words worthy citizens, who funded and supported charities, could authorise relief for those they deemed worthy.

The second was interview. Each week charities opened their doors and those seeking assistance had to wait, usually on long benches in large waiting rooms, often for hours, to undergo interview by philanthropists. Charities made inquiries into their circumstances, often involving home visits to verify the detail given at interview. If the committee was satisfied that the applicant was genuine then a recommendation for relief was authorised.

Finally, charities, anxious that applicants might try to deceive them, insisted on the right to visit recipients on a regular basis. Charities commonly had volunteer visitors, often women who had the time and inclination to devote to philanthropy, whose task was to check on all recipients of relief. This involved inspecting the state of the house (clean and respectable or untidy), the character of the recipients (evidence of drunkenness or prostitution) and whether those receiving relief were deceiving the organisation (for instance if a widow had found a male companion). These inquiries could be intrusive and punitive. The aim was to remove people from assistance; those who didn't conform to middle-class ideals of respectable impoverishment faced the prospect of being denied or taken off relief. Philanthropists sought to assist only the genuinely needy and recommendation, interview and visiting were thought essential to this end. Assistance was not a right but a privilege granted by philanthropists to those who passed their tests of character and whose circumstances warranted relief.

In the charity system, philanthropists were seen as the only people with the moral worth to be able to distinguish between the deserving and undeserving poor. They feared the system would collapse if the undeserving gained support and thus vigilance was essential. Handing the reins of power to government officials, even if governments provided most of the funds, might foster a false sense of entitlement amongst the poor. Government officials, philanthropists believed, would not have the incentive to police the moral boundaries of poverty. In reality, however, the demand for assistance often overwhelmed charities. They lacked the resources to conduct long interviews or visit on a regular basis and thus many recommendations were signed with only the most perfunctory of interviews. Moreover, because the public purse supported most charities, government officials had the right to sign recommendations. When charities opened their doors each day to long lines of applicants, many of them suffering dire hunger and poverty, the inclination and imperative to assist led to shortcuts and hasty decisions undermining rigorous enforcement of charity rules. [14]

Outdoor and indoor relief

There were [media]two main forms of charitable relief. Outdoor relief was food and clothing to sustain poor families during times of hardship. In Sydney the Benevolent Society was the most important provider of such relief. Each Wednesday those who had been recommended, after interview and inspection, trudged up Devonshire Street to the Benevolent Asylum with their relief tickets in hand. There they waited in long queues to receive their ration of food and clothing. By the second half of the nineteenth century, nearly 1000 families a week were supported by the Society. Other organisations provided support. Small charities assisted where they could, feeding and clothing a few families in their local suburb. Local churches and lay religious organisations, such as the Catholic St Vincent de Paul Society or the Anglican Church Missionary Society provided food and clothing rations to a substantial number of struggling families. Sometimes outdoor relief was occasional rather than regular. From the mid-nineteenth century, each Christmas, the Lord Mayors of Sydney would hold a special dinner for the city's poor. [15]

For many of the poor, however, their misfortune could not be addressed by the provision of sustenance. The ill, injured, aged and infirm, insane, orphaned and delinquent children, and drunks could not survive on rations – they needed care, accommodation and, for some, moral reform. This became known as indoor relief.

Nineteenth century philanthropists and evangelical reformers were fervent advocates of the transforming power of institutional life. At the heart of philanthropy lay a pervasive belief that the poor, lacking moral rectitude, were in some sense responsible for their own fate. In institutions they could be brought under the reforming influence of daily routine, religious instruction and contact with morally upright philanthropists. These influences would encourage the poor to reform and become respectable and self-sufficient. Asylums and hospitals were also places of last resort, places to accommodate those in their final days.

Large, often grandiose, institutions dotted Sydney's landscape. The Benevolent Asylum in the city not only dispensed rations but also contained wards for the care of the aged and infirm and a maternity ward for newborns. By the 1860s it was admitting up to 700 inmates a year. Large asylums for lunatics were opened at Tarban Creek (1838) and Callan Park (1880). Sydney Hospital expanded, dominating Macquarie Street. In 1853 The Society for the Relief of Destitute Children opened a substantial asylum in Randwick (now part of Prince of Wales Hospital), which at its peak had an inmate population of 700. Churches were active asylum builders. By the end of the nineteenth century the Catholic Church operated an asylum for orphaned and delinquent boys at Westmead, and a number of major hospitals, including St Vincent's in Darlinghurst. Many of these institutions were old convict barracks or other buildings turned to new purposes. [media]The Parramatta Female Factory later accommodated, in different sections, facilities for the insane and the aged. In 1906 the Protestant Boys' Orphan Asylum at Rydalmere became a lunatic asylum. There were also numerous small homes and cottages operated by charities. The Ashfield Infants' Home and the Sydney Female Mission Home only admitted 30 to 50 inmates a year by the late 1880s but these were still vital facilities for the struggling classes. [16]

Overcrowding was rife in most charity asylums and hospitals and conditions often pitiful. In the 1860s the Benevolent Asylum was overcrowded, dilapidated and filthy and during heavy rains inundated with burial refuse from the nearby cemetery. At the same time, visitors to Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum (in Gladesville) discovered cells crawling with rats and cockroaches. At Sydney Hospital there was insufficient water to wash patients after surgery, inmates slept on the floor and rats mutilated bodies left in the morgue. [17]

Challenging charity

It is little wonder that charity was stigmatised, something feared and best avoided. Workers and their families resisted the implication that they were morally at fault if the vicissitudes of life left them impoverished and dependent. They resented the fact that charity was a gift bestowed at the whim of the better off not an entitlement. Thus many working families sought to make their own provision for hard times. A weekly subscription to a Friendly Society, to cover unexpected medical and funeral expenses, was a common resort. By the 1880s there were 35,000 friendly society members in New South Wales. [18]

Charities, supported by government revenues, were fundamental to the provision of health and welfare services in nineteenth-century Sydney. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, a series of movements emerged challenging the censorious, moral policing principles underpinning charity, insisting that health and welfare should be a right not a gift. Others saw that social problems confronting progress required a more coordinated and comprehensive approach than that offered by charities. Thus trade unions, doctors, psychiatrists, child welfare experts, progressives and other social reformers sought to move beyond charity. Out of this ferment emerged what has become known as the welfare state, providing more systematic provision for those suffering misfortune. After Federation of the colonies, both Commonwealth and State governments became major contributors to the health and welfare of Sydney's population. [19]

Labour demands

One powerful force for change was the labour movement. The growing popularity of trade unions underpinned a larger desire for improved wages, sufficient to sustain independence rather than dependence. The escalating level of industrial conflicts between capital and labour, most evident in the great strikes of the 1890s, encouraged some liberal reformers to embrace reforms that mediated the interests of both capital and labour, favouring harmony over conflict. They supported the introduction of conciliation and arbitration systems to achieve reasonable wages without destroying industry. On the national stage the labour movement supported the idea of a 'living wage', remuneration sufficient to support a man and his family, a principle enshrined in the famous 1907 Harvester Judgement of the Commonwealth Arbitration Court. [20]

Agitation by the unemployed added to the growing demand for state rather than philanthropic solutions to distress. By the second half of the nineteenth century, periodic recessions (in 1872, 1884 and 1887) caused high unemployment. Governments sought to alleviate the situation and prevent the growth of a disgruntled urban unemployed class by establishing a Government Labour Bureau, which found positions in the country and provided railway passes for men to travel there. Many of the unemployed, however, resented having to wait in long queues at the Bureau in Prince Alfred Park for positions miles from home at low rates of pay. Worse, sometimes the position had been filled by the time they had travelled up country.

[media]Groups of unemployed began to organise protest marches, demanding a right to work and a fair day's pay. In the 1880s and 1890s, riots by unemployed men sparked by the punitive nature of assistance and the unscrupulous practices of employers driving down wages when there were men eager for any work, forced governments to provide public relief work to support the unemployed. Public relief work again became a major way the government dealt with serious unemployment and unrest during the Great Depression of the 1930s, although by then the gap between government provision and need was so great that the weakness of such piecemeal solutions fostered efforts to introduce unemployment payments to alleviate distress. [21]

The age pension

Others felt the sting of charitable dependence. Men and women from the working poor feared the consequences of age and infirmity. Being confined to overcrowded and dispiriting asylums, and mistreated and abused by staff and inmates, seemed poor recompense for a life of honest toil. Philanthropists too came to see that aged and infirm asylums were neither fair nor appropriate. Revelations of horrific conditions in these asylums, the ageing population (the proportion of the population over 60 years rose from 2.75 per cent to 6.5 per cent in the 50 years after 1861) and the costs of building and maintaining expensive asylums was proving to be a burden that charities and governments were finding difficult to bear. Charities such as the Benevolent Society experimented with paying a small allowance to the aged in an effort to keep them at home. [media]By the mid-1890s, prominent Sydney charity workers Arthur Renwick and Reverend FB Boyce established an Old Age Pensions League, to press for the payment of a small pension to the respectable poor in preference to incarceration. The campaign made headway and in 1901 the New South Wales Parliament introduced an old age pensions scheme. The federal government followed suit in 1908. Pensions represented a break with the charity principles: more a right than a gift. There were means and assets tests to limit the liability of governments but pensions involved little interrogation, no demeaning visits or humiliating incarceration. Pensions heralded the beginnings of the twentieth century welfare state. [22]

Supporting children

Fears for future generations also drove change. By the early twentieth century, concern about Australia's falling birth rate and high infant mortality rate and, for some, the belief that the dissolute poor were breeding more than the respectable classes, promoted population policies. In 1912 the federal government introduced a maternity allowance (baby bonus) to help mothers meet the medical costs of giving birth. State and local governments established baby health clinics and home nursing services to combat the problem of poor infant nutrition. [media]In 1904 Sydney City Council opened such clinics in Alexandria, Newtown and Balmain. School medical services were also introduced to ensure early identification of health and nutrition problems in children. Richard Arthur, New South Wales Minister for Public Health (1927–30), authorised the provision of milk for every school child.

Governments also became more active in dealing with the problem of neglected and delinquent children. In 1905 New South Wales established a children's court (originally in Albion Street) to ensure that such children were placed in the right form of care, preferably with their parents and supported by a small allowance, but if necessary in foster homes or small cottage institutions. In 1923 New South Wales established a Child Welfare Department to manage the myriad of charitable and government homes for wayward children. The following year the Lang Government introduced the first child endowment scheme in Australia to help parents to care for children. [23]

'Protecting' Aboriginal people

Running counter to the growing belief that neglected and wayward children should remain at home rather than be sent to large impersonal institutions was an increasing interest in removing Indigenous children from their families. From the 1870s the establishment of Aboriginal reserves under government supervision was combined with a policy of removal of Aboriginal children, particularly those considered 'half-caste' and placing them in large institutions for training as apprentices and domestics. The extensive system of native reserves was not dismantled until the 1950s and 1960s when policies of assimilation and a growing Indigenous civil rights movement led to the dissolution of paternalist protection policies. Some Aborigines moved into Sydney, around Redfern, or moved back and forth between rural communities and urban enclaves where unemployment, poor health and problems of drug and alcohol abuse stimulated the introduction of Aboriginal health, welfare and legal services, oftentimes operated by Aborigines themselves (with government funding), to address the particular needs of Sydney's Indigenous Australians. [24]

Changing health and welfare

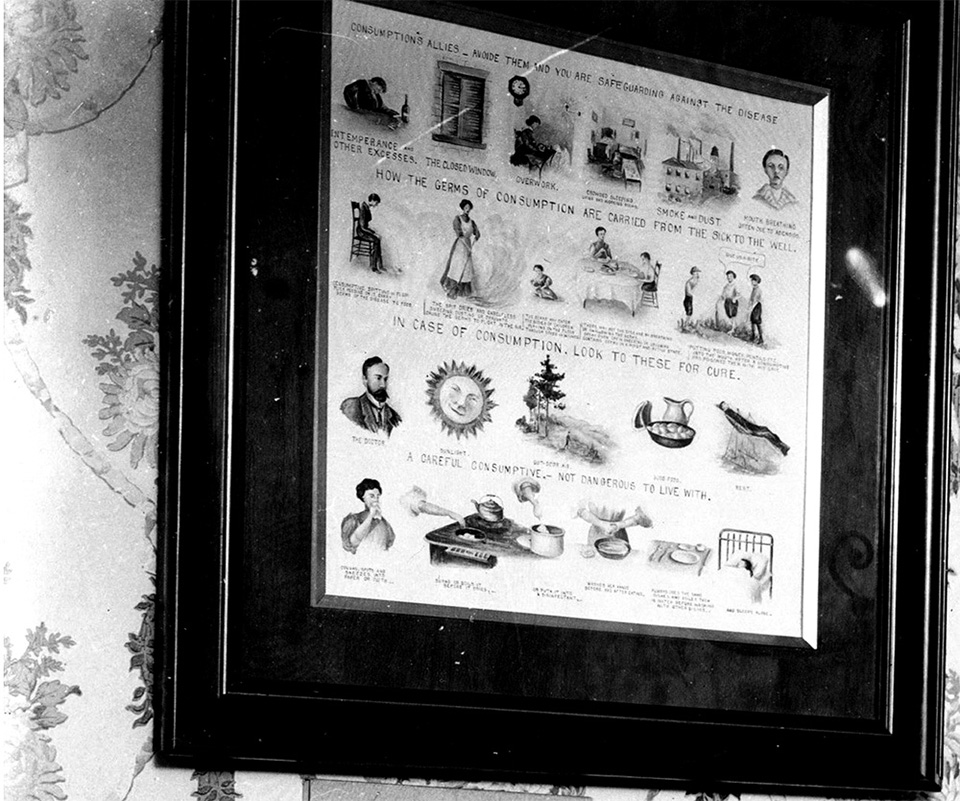

Health services were also undergoing profound change. Concern about the impact of epidemic disease, criticism of unsatisfactory conditions in hospitals and significant advances in medicine (arising from Listerism and the [media]germ theory) gave doctors new confidence in their capacity to cure. They supported a move away from the idea that hospitals were places for the poor towards the view that they were institutions where all citizens might undergo expert curative treatment. The nineteenth-century charity hospital was gradually replaced by the twentieth-century public hospital. Preventive health also emerged as an important area for government intervention. [media]A series of late nineteenth and early twentieth century epidemics – including a number of bubonic plague outbreaks in Sydney between 1901 and 1910 and Spanish flu in 1918 – fostered greater concern with hygiene, sanitation, quarantine and vaccination programs. [25]

War also had a major impact on health and welfare. After World War I the establishment of a comprehensive repatriation system created a second, parallel, and more generous welfare state for returned servicemen: pensions for returned men and widows, employment preference schemes, free hospital care, mental health services and rural settlement schemes. While public funds supported and governments administered the repatriation system, private charities also contributed with comfort funds and numerous private hospitals and homes for ill and injured soldiers and war widows and children. The gap between the small civilian welfare state and the extensive returned services welfare system did not begin to narrow until World War II. During the 1940s new welfare benefits for all citizens were introduced as part of a broader postwar reconstruction effort: unemployment benefits, national child endowment, pharmaceutical subsidies and widows' pensions. It was not until 1973, however, that the Whitlam Federal Labor Government introduced a national medical and hospital benefits scheme, overcoming the resistance of the medical profession to government regulation of medical services. [26]

The retreat from institutions

The increasing involvement of governments in the provision of welfare and health benefits, however, imposed a significant burden on the public purse. The old Victorian charity institutions that were still integral to public health and welfare services were expensive to operate, requiring significant upkeep and maintenance. [media]Equally important new movements for social reform in the 1960s and 1970s – feminism, gay rights, prisoner action, Indigenous civil rights, anti-psychiatry and community activism – questioned traditional policies of institutional care, arguing that they were forms of social control for those who deviated from middle-class norms of behaviour rather than places for genuine care and assistance. Many of these groups established alternative community based welfare systems. Feminists opened women's refuges to assist victims of domestic violence, such as Elsie Women's Refuge in Glebe, or community health services geared to the needs of women, such as Leichhardt Women's Health Centre. In the 1980s, when AIDS was identified as a major infectious disease, gay rights groups established special health care services in Albion Street, Sydney, and elsewhere, to promote preventive sexual health practices in the gay community. [27]

Many of these reform movements shared an antipathy to large psychiatric institutions. Public revelations of appalling conditions in mental hospitals such as Callan Park, resulting in a 1961 Royal Commission, cemented the image of these institutions as places of incarceration rather than therapy. Reformers advocated policies of 'de-institutionalisation', removing patients to community-based treatment facilities and integrating them into the wider society. Governments embraced such policies, in part to alleviate the fiscal burden of sustaining these Victorian institutions. In 1983 the comprehensive Richmond Report on mental health and mental disability services in New South Wales recommended the closure of all the old mental asylums with patients sustained by a comprehensive community services. Over the next decade many of the old institutions were sold off or turned into education, art school and other facilities. Critics claimed that governments failed to fund sufficient community services, leaving former inmates in a twilight world of hostels and boarding houses, maintained by high levels of medication or incarcerated in other institutions such as prisons and reformatories. [28]

Public–private partnership

Closing down older institutional forms of care did not solve the fiscal problems confronting the welfare state. By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries an emerging neo-conservative and neo-liberal discourse arguing that the welfare state was a bloated and wasteful bureaucracy, inherently inefficient, and fostering dependency rather than self-sufficiency, encouraged governments to gradually downsize and outsource health and welfare services to charities and private operators.

Increasingly churches and non-government organisations such as the Smith Family, Salvation Army, Sydney Mission, Anglicare and St Vincent de Paul moved into the frontline of service provision for those suffering poverty, distress and misfortune. Governments sustained welfare payments and funded hospitals and other essential services, but the non-government sector, supported by government subsidy, was still centrally involved in the provision of community health and welfare services. The size and complexity of health and welfare services has increased exponentially since the early years of colonial settlement but the partnership between governments and charities has remained at the heart of solutions to the problem of misfortune.

References

Cora Baldock and Bettina Cass (eds), Women, social welfare and the state in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

Peter Beilharz, Mark Considine and Rob Watts, Arguing about the welfare state: the Australian experience, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1992

Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980

Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990

Adam Graycar (ed), Retreat from the Welfare State: Australian social policy in the 1980s, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983

Michael Jones, The Australian Welfare State, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1980

Thomas Kewley, Social Security in Australia, 1900–1972, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1973

Stuart Macintyre, Winners and Losers: the pursuit of social justice in Australian history, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985

Ronald Mendelsohn, The Condition of the People: social welfare in Australia 1900–1975, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1979

Anne O'Brien, Poverty's Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880–1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988

John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes: Destitute and Neglected Children in Colonial New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986

Notes

[1] 'Heads of a Plan, 1786' in CMH Clark (ed), Select Documents in Australian History, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, pp 35–6

[2] Lois Davey, Margaret Macpherson and FW Clements, The Hungry Years: 1788–1792, Melbourne University Pres, Melbourne, 1947; Alan Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia: A History Volume I, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1997, pp 220–40; Jan Kociumbas, The Oxford History of Australia Volume II: 1770–1860, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992, pp 1–62; Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 1–29

[3] 1828 Muster; Jan Kociumbas, The Oxford History of Australia Volume II: 1770–1860, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992, pp 1–62

[4] Stuart Macintyre, Winners and Losers: The Pursuit of Social Justice in Australian History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985; Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 1–29; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 15–22

[5] David Fraser, The Evolution of the British Welfare State, 2nd edition, Macmillan, London, 1984; David Harvey, English Philanthropy 1660–1960, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1964

[6] Gertrude Himmelfarb, The Idea of Poverty, Faber & Faber, London, 1984; JD Poynter, Society and Pauperism: English Ideas on Poor Relief 1795–1834, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969

[7] Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 30–66; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 43–61; Anne O'Brien, Poverty's Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880–1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988

[8] John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes: Destitute and Neglected Children in Colonial New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986, pp 1–23

[9] Jack Brook and JL Kohen, The Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1991

[10] Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 44–7; CJ Cummins, The Development of the Benevolent Asylum 1788–1855, New South Wales Department of Health, Sydney, 1971

[11] Select Committee on the Benevolent Asylum, New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, vol 2, 1861–2, Minutes of Evidence, p 2

[12] Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, vol 14, p39

[13] David Fraser, The Evolution of the British Welfare State, 2nd edition, Macmillan, London, 1984, pp 40–42

[14] Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 43–61

[15] Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 30–66; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 48–54; Anne O'Brien, Poverty's Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880–1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, pp 33–8

[16] Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 30–66; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 54–61; Anne O'Brien, Poverty's Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880–1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, 202–11

[17] Select Committee into the Sydney Benevolent Asylum, New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, vol 2, 1861–2; New South Wales Royal Commission into Public Charities, New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, vol 6, 1873–4; Stephen Garton, Medicine and Madness: A Social History of Insanity in New South Wales, 1880–1940, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1988, p 161

[18] Royal Commission into Friendly Societies, New South Wales Votes and Proceedings, vol 3, 1883

[19] Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 96–140; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 62–109

[20] John Rickard, Class and Politics: New South Wales, Victoria and the early Commonwealth, 1890–1910, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1976; Stuart Macintyre and Richard Mitchell (eds), Foundations of Arbitration: the origins and effects of State compulsory arbitration, 1890–1914, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989; PG Macarthy, 'Justice Higgins and the Harvester Judgement', Australian Economic History Review, vol ix, no 1, 1969, pp 17–38

[21] Colonial Secretary's Department Special Bundle, Casual Labour Board 1887–89, New South Wales State Records, 4/891; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 72–7; Anne O'Brien, Poverty's Prison: The Poor in New South Wales 1880–1918, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, pp 66–71

[22] Jill Roe, 'Old Age, Young Country: The First Old Age Pensions and Pensioners in New South Wales', Teaching History, July 1981, pp 23–8

[23] Neville Hicks, This Sin and Scandal: Australia's Population Debate 1891–1911, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1978; TH Kewley, Social Security in Australia 1901–1972, 2nd edition, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1973, pp 99–116; Michael Roe, Nine Australian Progressives: Vitalism and Bourgeois Social Thought 1890–1960, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1984, pp 1–20; Stephen Garton, 'Sir Charles Mackellar: Psychiatry, Eugenics and Child Welfare in New South Wales 1900–1914', Historical Studies, vol 22, no 86, 1986, pp 21–34

[24] Peter Read, The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883–1969, New South Wales Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, Sydney, 1985; Richard Broome, Aboriginal Australians: Black Response to White Dominance, 1788–1980, Allen & Unwin, Kensington, 1982, pp 170–201

[25] Peter Curson, Plague in Sydney: anatomy of an epidemic, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1989; Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp: Sydney 1870–1890, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, pp 69–100; Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 101–11

[26] Clem Lloyd and Jacqui Rees, The Last Shilling: A History of Repatriation in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Vic, 1994; Stephen Garton, The Cost of War: Australians Return, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1996; Brian Dickey, No Charity There: A Short History of Social Welfare in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1980, pp 219–22

[27] Stephen Garton, Out of Luck: Poor Australians and Social Welfare, 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1990, pp 162–8; Cora Baldock and Bettina Cass (eds), Women, Social Welfare and the State, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983

[28] Stephen Garton, 'Changing Minds' in Ann Curthoys, Allan Martin and Tim Rowse (eds), Australians Since 1939, Fairfax, Syme and Weldon, 1988, pp 343–55

.