The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Utzon's Opera House

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Utzon's Opera House

[media]There are many myths about Sydney's Opera House and divided opinions (still) about its architect, Jørn Utzon. Mies van der Rohe considered it the 'devils work' [1], while Frank Lloyd Wright didn't consider it architecture at all; rather, it was a 'circus tent', an 'inorganic fantasy' that merely reveals 'the folly of these now-too popular competitions' [2]. American architect Louis Kahn wrote that 'the sun did not know how beautiful its light was, until it was reflected off this building' [3] and Harry Seidler described Utzon's 1957 competition winning scheme as 'poetry, spoken with exquisite economy of words' [4]. And this from a losing entrant!

There are stories that it was inspired by sails, sea shells or oranges. I once heard a young girl proudly telling her father as they approached the building that it was designed by 'the man that peeled a mandarin'. And the architect, well, he was a sculptor, not an architect; impractical and interested only in form. A visionary but also slow, expensive, arrogant and so on.

So how did this sun-drenched former penal colony, not noted for its charm or sophistication even within Australia, snare this rare beauty? And how could its architect be so divisive and misunderstood when his first public building so quickly came to define a city?

Utzon's method

Utzon was an architectural enigma. He won Sydney's first and last single-stage, open international architectural competition at the age of 38 having completed nothing larger than a single family house. He was warm, shy and charming with movie star looks (the Australian Women's Weekly described him as 'a young Gary Cooper, only better looking' [5]). The son of a naval engineer, he spent his formative years in his father's ship yard in Alborg drawing, making and racing yachts. These experiences taught Utzon about the relationship between form and performance – form following function – as well as important lessons in reading landscape.

Utzon ascribed to a method, not a style. When designing, he would ask the same questions and pursue the same lines of inquiry, regardless of project or scale. By definition, if you ask the same questions and the parameters change (site, context, brief, budget and so on), then unique solutions are found every time. For Utzon, each project was a chance to return to first principles. Like a detective in a foreign landscape, he would set off with an open and inquisitive mind, quietly researching and agitating the context in order to see what emerged, and when things did, he would respond decisively.

Nature was his primary inspiration and it was a study of Sydney's navigational maps that gave him his opening gambit and enduring motif for the Opera House. Studying Sydney's geology, he observed the way the sandstone fingers behave as they approach Sydney Harbour, falling gently before rising slowly then hitting the water in a series of vertical and horizontal shelves. The platform of Sydney Opera House is a gentle abstraction of Sydney sandstone. The heavy concrete base clad in horizontal and vertical stone panels gives the city its great amphitheater, hiding within its walls the building's functions, providing the springing point for the 'clouds' that hover above (the minor hall, major hall and restaurant) while continuing the city's geological pattern. Clouds – not sails – hover above the platform.

Utzon was not preoccupied with the forms nature produced, nor was he concerned with some kind of organic aesthetic. Rather, he was interested in nature's generating principles. Covering the 'clouds' in ceramic tiles was a rational decision when you consider he wanted the building to last 2,000 years (he stole the solution from the Persians) but unlike these ancient precedents, Utzon's 'tiled lids' were prefabricated from a family of plywood moulds and sit directly over the structural vaults. This is beautiful but rational and pragmatic at the same time: beautiful because the skin relates to the structure and rational because it allows the vaults to move independently. A study of glaciers, the way water plays with sunshine, the skin of fish, even fragments of Japanese porcelain, helped refined his architectural solution; nature as inspiration at every scale.

Utzon had little interest in the work of his contemporaries unless he considered them to be masters, that is. He loved the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, a love that was clearly not reciprocated. He adored the work of Ray and Charles Eames, LeCorbusier, Louis Kahn as well as Scandinavian masters like Aalto, Lewerentz, Jacobsen, Saarinen and Asplund. But his real love was the architecture of the ancients, works that had withstood the test of time. If an idea was any good, he figured, it would still be good a thousand years later. So the Greek, Roman, Mayan, Persian and Gothic traditions all play out decisively in Sydney. The platform is a Mayan platform (Utzon travelled to Chichen Itza in Mexico in 1949 to study the ruins) informed by a careful study of the Greek and Roman amphitheaters, the gathering spaces of the ancients. The vaults are gothic, albeit with a different geometry, and the skin is Persian. These ideas were stolen, translated then explored in a completely modern way, taking leading edge technology and pushing it into uncharted territory. So the building remains utterly contemporary yet was informed by projects at least 1,000 years old, one of many charming contradictions in the Sydney Opera House.

Utzon's third conceptual line was the notion of counterpoint or complimentary opposition. Counterpoint is a musical term whereby one combines 'two or more melodic lines in such a way that they establish a harmonic relationship while retaining their linear individuality.' [6] The 'clouds', for example, hover dramatically over their heavy base; they are curved against the sharp horizontals and verticals of the platform. Something light plays against something heavy, shiny against matt, public against private, performance against function, and so on. If you look carefully at the ceramic skin, you see there are two different glazed tiles: one rough, shiny and white, the other smooth, matt and off-white. Utzon likened their relationship to 'snow against ice' and best of all, the 'tiled lids' were prefabricated so it was quick to erect with all the economic, time and quality benefits of mass-production.

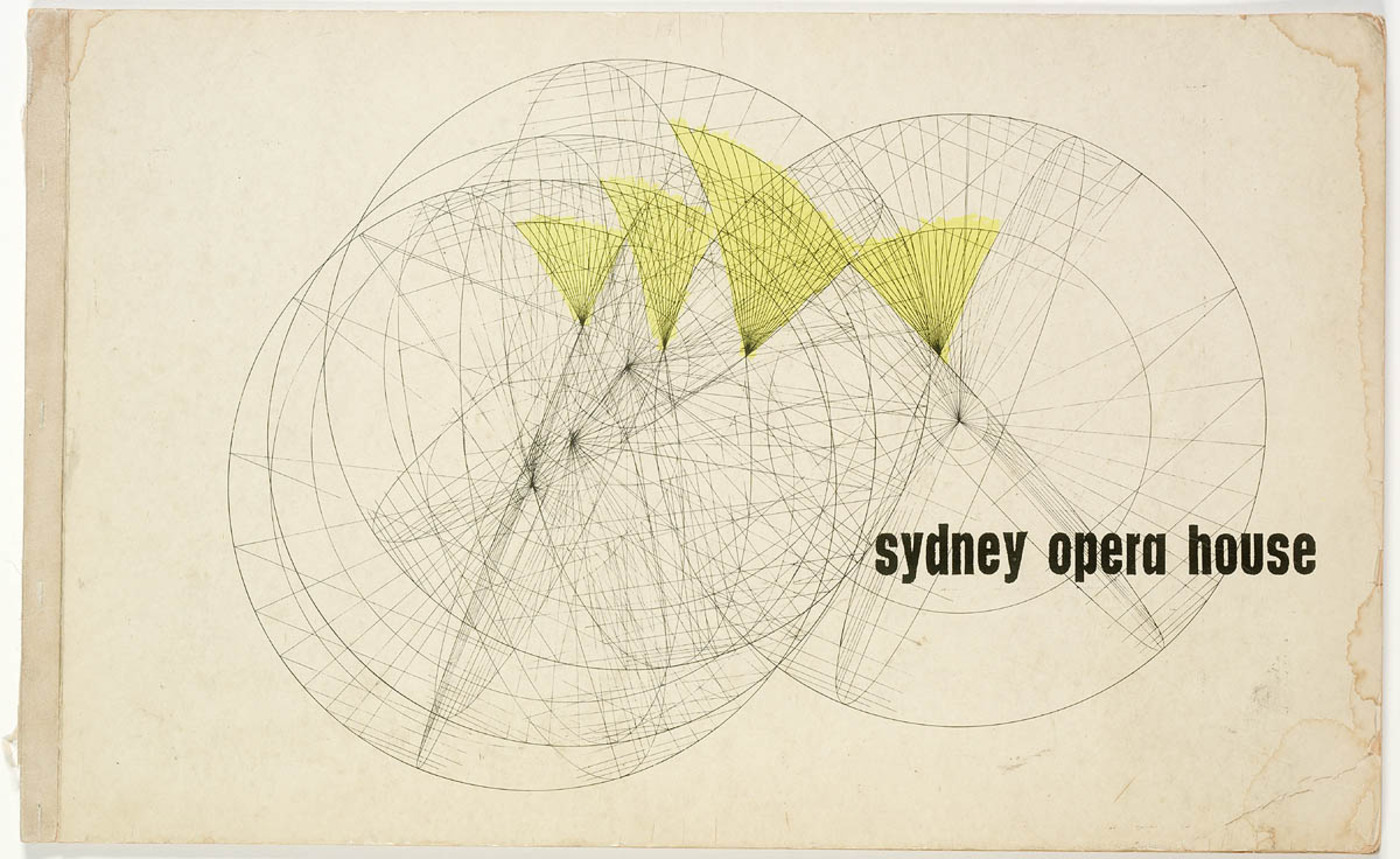

So what about that orange? Play was central to Utzon's creativity and in the fifth year of construction, after almost 120,000 engineering hours spent pursuing structural and geometric alternatives for the 'shells' – none of which worked satisfactorily – the architect stumbled across a solution as elegant as it was simple. Perhaps the geometry of each of the 'clouds' could be derived from a constant form such as the surface of a sphere; a repeating radius that would allow the vaults to be constructed from a small family of elements and in turn, a uniform pattern could be achieved for the tiling of the exterior. The one, unifying geometry linking all the spherical surfaces is a radius of approximately 74 metres, a solution that was explained by peeling an orange and laying out its wedged-shaped segments in a certain way. Childs play!

A ruin one day

Bill Wheatland was Utzon's principal Australian assistant during his final years in Sydney. After Utzon left Australia for the last time in April 1966, Bill spent a number of years cleaning up Utzon's office, archiving his drawings and models and organising his legal fight for unpaid fees. The building Utzon left behind was deep in construction and while the platform and vaults were more or less complete and the ceramic skin well under way, the six years of work invested in the design of the glass walls ('suspended curtains in bronze and glass') and acoustic interiors ('two "exotic birds" perched within the bleached concrete skeleton') had not started on site – and thanks to the irascible Askin state government, nor would it. Utzon described this period between 1960 and 1966 as the most productive of his career and sadly, there is little to show for it apart from drawings, models and prototypes; a half-finished monument to New South Wales' politics of compromise.

With Utzon gone, the new client appointed a committee of local architects to complete the project. The brief changed dramatically – the function of the major and minor halls were swapped – rendering Utzon's interior designs redundant and, at great expense (the non-Utzon interiors cost four times the sum of the platform, vaults and skin [7]), the building was finally opened in October 1973.

On his way back to Denmark, having left Sydney for the last time, Utzon sent Bill a postcard from New York depicting a Myan temple. It read: 'Went to Yucatan. The ruins are wonderful, so why worry? Sydney Opera House becomes a ruin one day.' [8]

References

Richard Weston, Utzon: Inspiration, Vision, Architecture, Edition Blondal, Hellerup, Denmark, 2002

David Messent, Opera House Act One, David Messent Photography, Balgowlah, NSW, 1997

Trevor Garnham, Kenneth Powell and Phillip Drew, City Icons: Antoni Gaudi, Warren and Wetmore and Jørn Utzon, Phaidon, London, 1999

Francoise Fromonot, Jørn Utzon: The Sydney Opera House, Christopher Thompson (trans), Electa Gingko, Corte Madera, California, 1998

Notes

[1] Richard Weston, Utzon: Inspiration, Vision, Architecture, Edition Blondal, Hellerup, Denmark, 2002, p 114

[2] David Messent, Opera House Act One, David Messent Photography, Balgowlah, NSW, 1997, p 112

[3] Utzon Design Principles, Sydney Opera House, Sydney, 2002, p 18

[4] Richard Weston, Utzon: Inspiration, Vision, Architecture, Edition Blondal, Hellerup, Denmark, 2002, p 119

[5] Eric Ellis, 'Utzon Breaks His Silence', The Good Weekend, 31 October, 1992

[6] 'Counterpoint', The Free Dictionary website, http://www.thefreedictionary.com/couterpoint, accessed 25 February, 2014

[7] Trevor Garnham, Kenneth Powell and Phillip Drew, City Icons: Antoni Gaudi, Warren and Wetmore and Jørn Utzon, Phaidon, London, 1999

[8] Francoise Fromonot, Jørn Utzon: The Sydney Opera House, Christopher Thompson (trans), Electa Gingko, Corte Madera, California, 1998, p 187