The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Workers' Educational Association in the post-war era

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Workers' Educational Association in the post-war era

The Sydney Branch of the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) was founded in 1913 with a democratic structure that enabled it to thrive in the postwar era and meet shifting community and government expectations of adult and continuing education, while remaining relevant and independent, into the twenty-first century.

The WEA in the city

[media]The WEA head office was originally located in the Department of Education building on Bridge Street, but by 1939 the state headquarters, lending library and club room of the WEA were in rented premises at Sirius House in Macquarie Place. Classes were held wherever space could be found, including the University, but tutors scrabbled to find venues, even using public schools, where adults learned on desks made for children.[1] This use of borrowed premises threatened the non-sectarianism of the organisation, as was the case in 1944 when the Unitarian Church found out the WEA was teaching a course on ‘Sex and Society’ in its hall and cancelled the booking.[2]

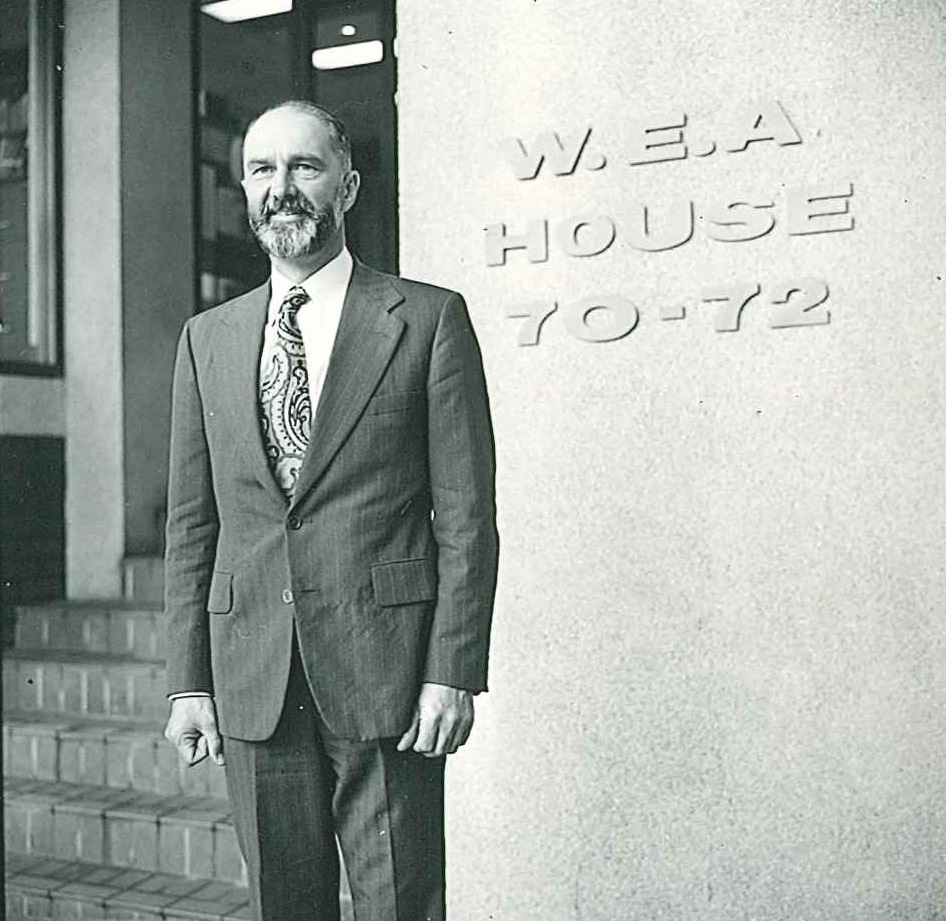

In 1948 Sirius House was sold and the WEA moved to the somewhat smaller premises of the basement of 4 Albert Street, Circular Quay. In 1950 the organisation moved again to more spacious and suitable rooms in St James Hall in Phillip Street.[3] In 1959 the Association bought 52 Margaret Street, which it named David Stewart House after the organisation's late general secretary, but quickly outgrew the building. A decade later it sold David Stewart House and bought 109-119 Liverpool Street, although it operated from rented premises at 52–54 Clarence Street. Opportunity struck in the form of developer demand, so the WEA sold Liverpool Street for twice what it had paid without ever moving in, and bought 70 and 72 Bathurst Street, which it redeveloped. The official opening of the WEA’s new seven-storey headquarters, WEA House, was on 4 December 1971.[4]

Meeting post-war challenges

At the end of the war WEA was clearly a leader in the field of adult education and its passion was legendary. Its principles that working people should be able to access the life of the mind and that learning should be participatory, non-vocational, and interested in social change, would be tested in the postwar adult education environment.[5]

[media]In 1944 WGK Duncan, director of tutorial classes at the University of Sydney, had surveyed adult education and concluded that most people who might seek adult education were ‘more interested in their jobs, their families, and their recreations than they are in public affairs.’ The WEA was focused on subjects that might be considered recreations, while University tutors spoke in abstract ways that were unintelligible to ordinary people.[6] The difficulty for the WEA was whether and how it should respond to market demand, as opposed to concentrating on studies relevant to social change.[7]

In the 1950s the Central Council decided to divide into regional areas. The Sydney area became WEA Metropolitan Region, and stretched north to Ourimbah, west to Katoomba and south to Helensburgh. The Newcastle area became the Hunter Valley Regional Council and the Wollongong District Committee was replaced by the Illawarra Regional Council.[8]

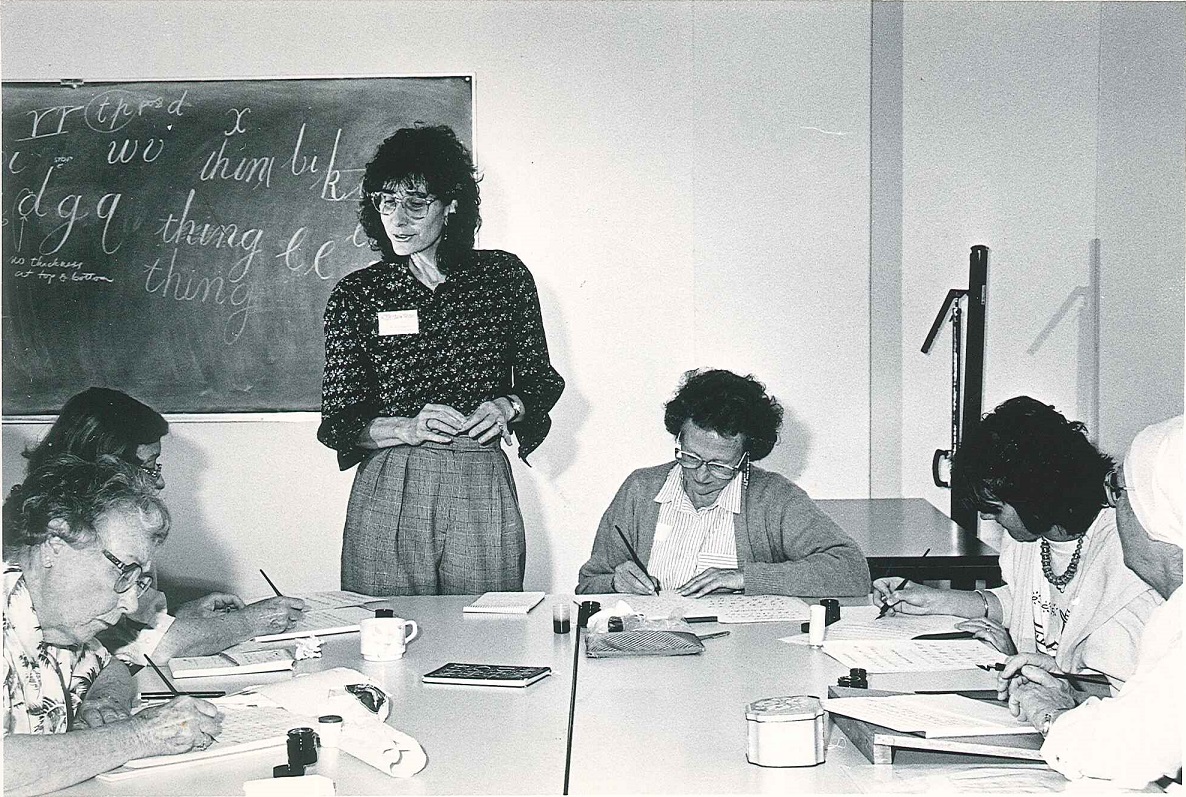

[media]The WEA still served workers – relations with the Labor Council that had suffered during the war had thawed, and it offered scholarships to the WEA Trade Union School and conducted psychology classes in the Eveleigh Railway Workshops. However, its courses were increasingly diverse, ranging from documentary film-making to French literature and languages. This led to some criticism that its offerings were outmoded and better suited to the middle classes and in a 1959 study concluded the liberal education offered by WEA was unsuited to the highly rural environment of contemporary Australia, and that WEA courses had a negligible effect on the trade union movement.[9]

[media]Though stinging, this criticism was not unjustified, especially when the WEA clung tightly to its traditions of providing liberal education, and trade union relationships were lessening in importance and fading away.[10] The WEA decided enrolments could be arrested by increasing its expectations of students and reintroducing three-year courses.[11] The organisation did modernise, although one might say it moved away from, rather than towards, the working class. In 1961, WEA introduced the first creative writing courses in the US model to Australian adult education and the writer Frank Moorhouse joined WEA Metropolitan Region as a tutor, assistant secretary, and, from 1964–1965 editor of The Australian highway, as well as the Australian Workers' Union The Worker[12]. That year the WEA Film Study Group was formed, and the WEA became the first adult education provider to venture into the relatively new medium of television when it partnered with TCN9 to launch a one-hour programme, Doorway to Knowledge, which aired four times weekly, for four terms a year, from 1960 until 1964.[13]

[media]During the late 1960s the Commonwealth Government had considered the recommendations of a report on the future of tertiary education in Australia and debated removing funding from adult education altogether, but the election of the Whitlam Labor government in 1972 shifted the focus of adult education once more. A series of inquiries was conducted into adult education and training looking at increasing offerings for less well-educated sections of the community. The WEA maintained its liberal and cultural streams but made concessions to the vocationalism of the age by introducing innovative computer training courses in 1973. By 1974, WEA Metropolitan classes exceeded 300 for the first time, with almost 10,000 students.[14]

Shifting relationships with Sydney University

[media]In 1963, the year the WEA celebrated its golden jubilee, the University of Sydney had abolished its Department of Tutorial Studies and established a Department of Adult Education. The University had never quite accepted the WEA's philosophy that students should set class content, and the new department was adamant that it should do so. This fanned long-standing grievances within the WEA about the University's tendency towards unilateralism. As government funding changed, the University and WEA found themselves on different sides of the funding stream. The Commonwealth Government now funded adult education through the Australian Universities Commission and from 1974 the WEA received its funds from the New South Wales Government's Board of Adult Education.

[media]Matters came to a head in 1979, when women in Class 177, ‘Varieties of Feminism’, voted to exclude three men from the course. They took their fight to the WEA’s Metropolitan Council, asserting their right as WEA members to manage class affairs democratically, but the University was disturbed that the rights of all students were not protected. In the end Class 177 was cancelled but the incident shone a light on the hostility between particular members of the WEA and those in the Department of Adult Education.[15] As the university’s finances declined, a vice-chancellor’s working party was already investigating the university’s role in adult education and in 1983 the University advised the WEA that it would no longer conduct joint programs, ending a 70-year relationship.

The 1980s

In 1980, the WEA introduced summer classes for the first time, and a range of courses that informed and entertained – yoga, home maintenance and other hobbies. It was a difficult period, with external review by the Adult Education Board and the WEA’s first years of operating without the involvement of the University, and a review of the WEA’s constitution and clarification of its educational policy was undertaken. Although only one-third of classes it offered fitted its traditional liberal education mould, and the Education Committee's recognition that Mansbridge’s ideals needed to be tempered, the WEA remained committed to its ‘special and distinctive objective’ of serious and critical study of nature and society, past and present, and of history and the arts. Non-partisanship remained a vital force within the movement, but the focus was now less on the worker than the general public, and the committee stated its willingness to provide courses in different locations within the city, and to cater to different social groups.[16] The traditional emphasis on discussion remained, and courses still consisted of lectures and tutorial groupings. The focus was on the humanities.

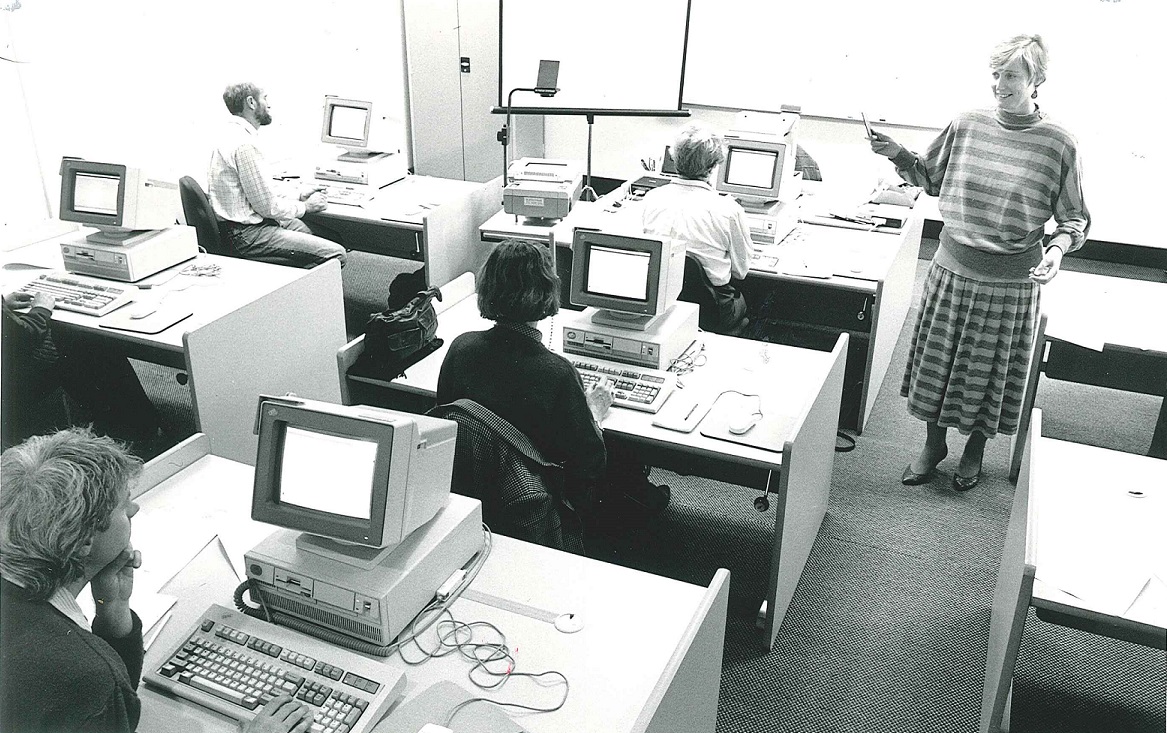

[media]With more than 15,000 students enrolled in the later part of the 1980s, the WEA remained a bastion of liberal adult education, despite considerable government pressure – funding was often tied to the delivery of vocational courses and competency standards. The WEA incorporated new courses, such as Arabic, and catered to hearing impaired students and in 1989 it established a Computer Training Centre at WEA House. But the organisation was, by then, in severely straitened circumstances – the Board of Adult Education cut WEA Metropolitan’s funding in half in 1988 under then Education Minister Rodney Cavalier.

At that point the WEA provided 30 per cent of student contact hours in New South Wales but received only 15 per cent of the available government funding.[17] With the change to the Greiner Government in 1988 the organisation had high hopes for the new minister Terry Metherell, a former WEA tutor, like his mother. It was not to be. Metherell condemned ‘cappuccino courses’ and New South Wales Government policy towards the adult and community education sector turned out to be in line with the Commonwealth Government’s National Training Agenda. Vocational education and competency-based training became the hallmarks of adult education. WEA met the challenge, enrolling nearly 17,000 students in 1992. Still, it continued to provide intensive humanities courses and in 1993 it also took over the Discussion Groups program pf the University of Sydney’s Centre for Continuing Education.[18] It also began to develop activities with organisations that were sympathetic to its aims, such as the Australian Museum, Blacktown City Council, and the Heritage Council of New South Wales.[19]

WEA Sydney

[media]In 1994 WEA Sydney, WEA Hunter and WEA Illawarra became separately incorporated entities. WEA Sydney’s enrolment at that point was more than 18,000, with a range of daytime and evening courses in creative and humanities subjects, 100 language courses, and 12 accredited vocational courses. The WEA also began to build new relationships, developing new courses with the State Library of New South Wales and a relationship with the University of New England. At a time when government policy was driving adult education to be a service, rather than a movement, the WEA held fast to its belief in liberal education. By the late 1990s, when enrolments reached nearly 20,000, the WEA had identified that achieving independence from government agencies was a worthy challenge.[20]

WEA Sydney prospered in the first decade of the new century as a registered training organisation (RTO), delivering corporate education, as well as its offering of vocational and other subjects, but in 2004 the New South Wales Government cut WEA’s grant by 35 per cent. The organisations expertise as an RTO meant it was well placed to deliver courses that were in high demand, such as Certificate IV in Workplace Training and Assessment, and it landed important contracts to deliver training to large CBD organisations, such as St George Bank.[21] Along with flourishing language courses, this training capacity provided it with the economic base to continue delivering its traditional, high quality liberal humanities courses, and attracting fine tutors. Former New South Wales Premier Bob Carr was delivering a lecture at WEA Sydney on the day in March 2012 that the news broke that then Prime Minister Julia Gillard had asked him to serve as Foreign Minister, and the Governor of New South Wales, Marie Bashir, attended lectures on her predecessors at WEA.[22]

By the 2000s, WEA Sydney had moved far from its origins and was no longer involved with the trade union movement or Sydney University, but it cleaved to its liberal principles. Truly independent, it was both a respected training provider and a collaborator with other respected humanities organisations.[23]

One hundred years on

In 2013, WEA celebrated its centenary and in 2018, still supports groups to organise, select a topic, and find a tutor to facilitate their learning, fulfilling Mansbridge’s vision of student-directed learning. It remains the preeminent provider of adult education in Sydney and serves the needs of more than 15,000 students a year. It does not receive government funding, or support from unions, and stands on its own two feet. The humanities and social sciences program remain at the core of the WEA.

The modern WEA mission statement would still be entirely recognizable to founders Albert and Frances Mansbridge and David Stewart:

WEA Sydney is a voluntary, independent, not-for-profit adult education organisation. Our mission is to provide adults with stimulating and varied educational activities which develop their knowledge, understanding and skills. Within our program we place special emphasis on providing opportunities for the serious and objective study of the arts, humanities and sciences.[24]

References

Darryl Dymock,‘A special and distinctive role in adult education’: WEA Sydney 1953–2000, Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001

EM Higgins, David Stewart and the WEA, Sydney: The Workers Educational Association of New South Wales, 1957

Moorhouse, Frank. The writer and the State: Patronage, national security and secrets, National Archives of Australia, Frederick Watson Fellowship paper, 8 February 2005, Canberra, http://www.naa.gov.au/Images/Moorhouse_tcm16-35763.pdf, viewed 10 August 2018

Jill Roe (ed), Social policy in Australia: some perspectives 1901-1975,Stanmore: Cassell, 1976

Michael Roe, ;Nine Australian Progressives: Vitalism in bourgeois social thought 1890–1960, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1984

Sydney Labour History Group. What rough beast: the state and social order in Australian history,Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1982

WEA Sydney, Workers’ Educational Association, Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning, Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013

Notes

[1] 'Letters To The Editor', The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 April 1946, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17976994, viewed 13 April 2018; 'Letters To The Editor Premises For Education' The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 January 1948, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18056299, viewed 13 April 2018

[2] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013)

[3] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 105–106

[4] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 107–109

[5] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 28–29

[6] WGK Duncan, 'Adult education in New South Wales', unpublished typescript, August 1944, cited D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 32

[7] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 33

[8] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 25

[9] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 34–36

[10] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 34–36

[11] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 40

[12] Frank Moorhouse, The writer and the State: Patronage, national security and secrets, National Archives of Australia, Frederick Watson Fellowship paper, 8 February 2005, Canberra, http://www.naa.gov.au/Images/Moorhouse_tcm16-35763.pdf, viewed 10 August 2018

[13] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 74–75

[14] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 42–47

[15] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 110–111

[16] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 48–51

[17] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), pp 144–145

[18] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013), pp 20–21

[19] D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 72

[20] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013), pp 20–21; D Dymock, 'A special and distinctive role in adult education': WEA Sydney 1953-2000, (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001), p 155

[21] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013), pp 22–23

[22] Personal communication, Michael Newton, 2018

[23] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013), pp 22–23

[24] WEA Sydney, WEA 100 years: Workers' Educational Association Sydney celebrates 100 years of lifelong learning (Sydney: WEA Sydney, 2013), p 1