The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Railways of Sydney: Shaping the City and its Commerce

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Railways of Sydney: Shaping the City and its Commerce

[media]Proposals to build railways in New South Wales first emerged in 1841. A public meeting was called on 24 January 1848 to present the surveyor's report on the route for a railway from Sydney to Goulburn. [1] The prospectus for the Sydney Tramroad and Railway Company (subsequently the Sydney Railway Company) was issued on 31 October 1848. From the outset the primary aim of the colony's railways was to assist inland primary producers to transport their produce to the port of Sydney for export and to open the country up for closer settlement. Improved transport for urban residents was a low priority.

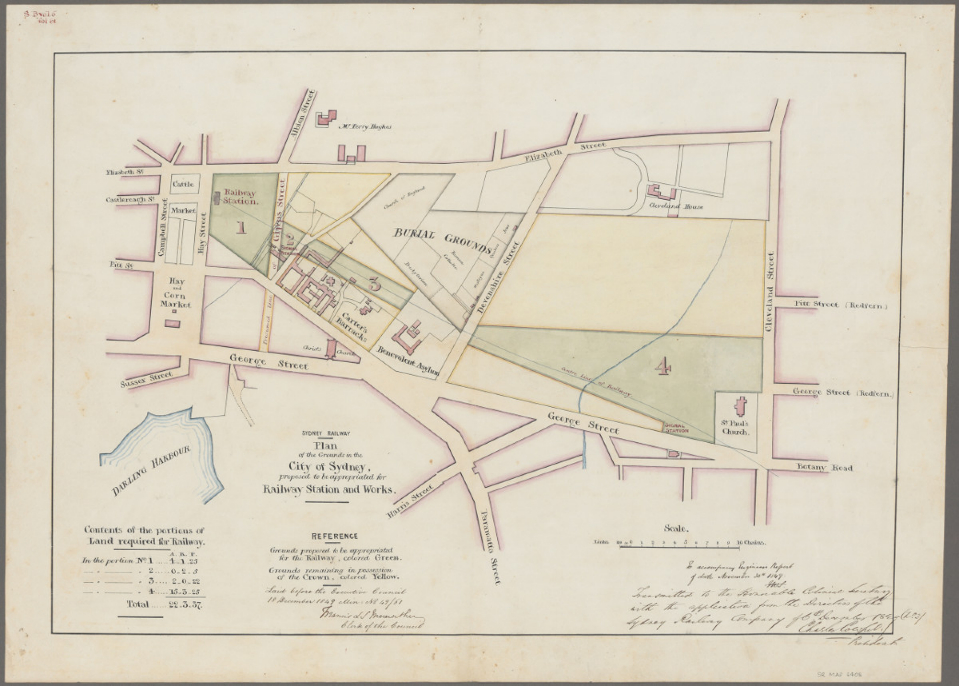

[media]The surveyor, Thomas Woore, proposed the location of the 'terminal station' along the western side of Darling Harbour, but this was quickly put aside when the first manager of the company, Charles Cowper MLC, decided that the terminus should be in the 'government paddock, by Cleveland House,' with a branch line to Darling Harbour. [2] This was an area of undeveloped land on the periphery of the city boundary where the teamsters who transported goods into and out of the city rested their horses and bullocks.

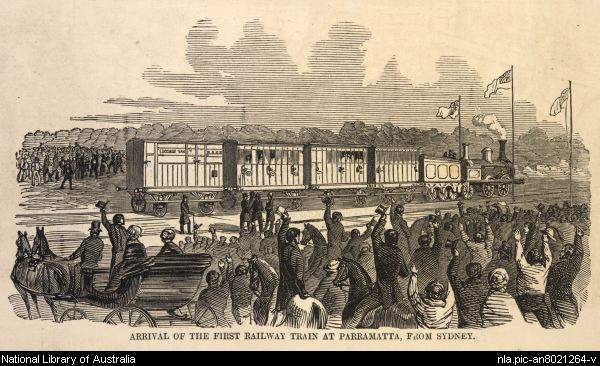

Governor FitzRoy's daughter, Mrs Keith Stewart, turned [media]the first sod for the railway in Cleveland Paddock on 3 July 1850. While the intended destination was Goulburn, the plans were to build the line to Parramatta in the first instance. Under-capitalisation and the regular changing of engineers brought numerous delays and variations in the scope of the works over the coming years, including a change of gauge from the agreed Irish gauge (5 feet 3 inches, or 1.6 metres) to the English standard gauge (4 feet 8.5 inches or 1.44 metres). As costs escalated and funds diminished, the company became increasingly dependent on the government for assistance. In December 1854 an act authorising the government's purchase of the Sydney Railway Company was passed and the assets were formally transferred to government on 3 September 1855.

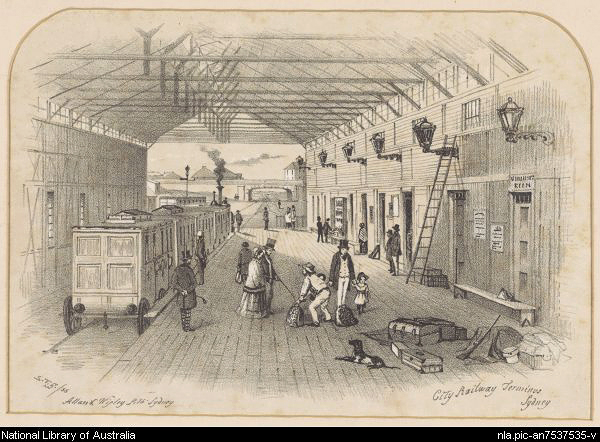

[media]A priority for the government was to reduce the capital cost of the railway. James Wallace, the engineer responsible for construction, produced plans for temporary stations at both terminals in July 1855. [3] The first Sydney terminal was a single wooden platform covered by a corrugated iron shed, 100 feet long and 30 feet wide (approximately 30.5 x 9 metres). An iron building with a lean-to roof housed the offices and public rooms, while there was a short branch line to Darling Harbour for goods traffic to and from the wharves. The official train for the opening departed from the station 'about twenty past eleven' on 26 September 1855.

[media]Because the terminal station was located on the periphery of the city, horse-drawn buses and cabs transported passengers through the city to Circular Quay. Within two months of his arrival the new engineer-in-chief, John Whitton, identified the extension of the railway into the city as a key priority with a proposed terminal station at Hyde Park. This would involve the demolition of St James' Church and the Supreme Court and the resumption of the northwest quarter of the park. The latter proposal, in particular, was unpopular with Sydney's citizens. [4]

Building the trunk railways

The high cost and slow progress of building the main lines over the Great Dividing Range provided ammunition for critics of Whitton's construction standards but once the mountains had been conquered the pace of construction quickened and costs were reduced.

With the return of Henry Parkes as premier and John Sutherland as secretary for Public Works in May 1872 there was a rising sense of optimism in the colony. The new ministry saw railways as crucial to transforming the social and economic landscape of the colony by opening up land for settlement, which in turn would generate revenue through land sales. [5] By March 1873 the railway network had been expanded to Goulburn in the southwest (220 kilometres), across the Blue Mountains to Raglan in the west (212 kilometres) and from Blacktown to Richmond (26 kilometres). The major towns on these lines were provided with imposing brick and/or stone station buildings.

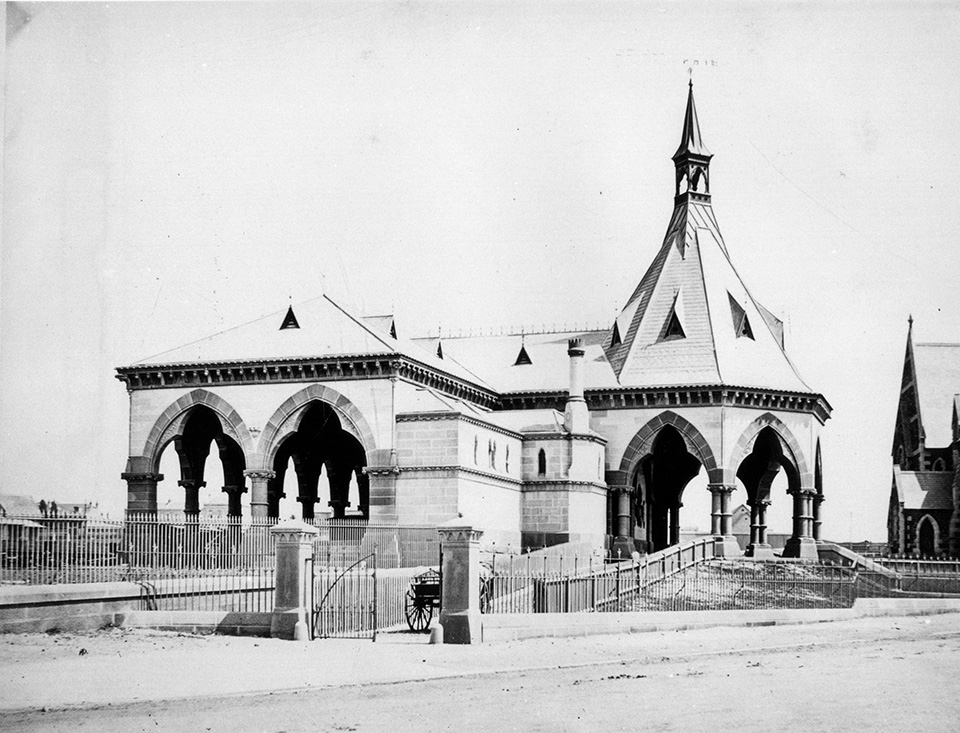

In [media]the frenzy of railway construction to service inland centres, the inadequacies of Sydney's temporary station became all too apparent. Its lack of facilities to cope with the increased traffic and its lowly status brought public agitation for a new building, particularly after the handsome sandstone Mortuary Station was opened nearby in April 1869 to cater for funeral trains to Rookwood Cemetery. [6]

Designed by the engineer-in-chief John Whitton in 1871, Sydney's larger and more permanent terminal station with its northern frontage on Devonshire Street was finally opened in 1874. [7] The brick building was in neo-classical style with decorative detail formed using polychromatic relief work. A two-storey administrative block was located to the west of the building, with the district superintendent occupying a first floor office. This station was generally referred to as Redfern while what is now Redfern Station was called Eveleigh.

Whitton's plans for a terminal station in the city proper failed to gain political support, but as the number of trains serving the station dramatically increased in the 1880s, a mishmash of additional platforms (eventually numbering 13) and supporting buildings were erected across the site.

Another main line was planned for the Sydney system in March 1881 when the Parkes ministry gave priority to construction of the then 95-mile (153 kilometre) double-tracked Homebush to Waratah line that would link Sydney with the Northern Railway system centred on Newcastle via the Central Coast. The Sydney to Newcastle Link Railway (colloquially known as the 'Short North'), 104.25 miles in length (168 kilometres), was finally completed with a lavish official opening ceremony of the Hawkesbury River Railway Bridge on 1 May 1889. [8] It branched from the Main Suburban Line at Strathfield and was served by a number of stations up to Hornsby.

Sydney's first suburban railway

The extensive land speculation in the boom years between 1870 and the late 1880s brought pressure from city-based land developers for the construction of new suburban passenger lines, but the powerful rural interests in the New South Wales Parliament rejected these proposals. Among the early lobbyists were Richard Hayes Harnett and the colonial treasurer Alexander Stuart (later premier, 1883–1885) who had developed the East Chatswood Estate in 1875 and, together with Michael McMahon, mayor of Victoria, lobbied for a railway to link their investment with Sydney Harbour at Milsons Point.

[media]Their efforts were unsuccessful. However, Henry Parkes, who had resigned as premier in 1883, ran for the seat of St Leonards in the October 1885 state election, against the sitting member and premier, George Dibbs. Parkes promised a bridge across Sydney Harbour and a railway line from Pearce's Corner at Hornsby to Milsons Point. The ambitious promises brought electoral success and when Parkes again became premier in January 1887, he appointed his long-standing colleague Sutherland as secretary for Public Works for his fourth term. Sutherland moved quickly to approve the line and the tender for its construction was issued in July 1887. A Harbour bridge would be a longer term project!

Because David Berry, the main landowner along the proposed route to Milsons Point, opposed the project, the initial tender was for a line from Hornsby to St Leonards. The railway commissioners agreed to construct the Chatswood station on Harnett's land and were duly recognised by Harnett who named streets in his North Shore Railway Estate after them before the land auction on 19 January 1889.

The colony slid into a deep economic depression in 1889 so there was little fanfare when the North Shore Line opened from Hornsby to St Leonards on 1 January 1890. Just four trains a day (with none on Sunday) were deemed sufficient for the traffic offering, while passengers relied on horse buses for transport between St Leonards Station and the ferry terminal at Milsons Point. The railway extension from St Leonards to Milsons Point opened on 1 May 1893. By 1895, Sydney's population had reached half a million people, the majority of whom lived in suburbs served by railways. [9]

Other suburban lines soon followed. The Illawarra Line route from Redfern to Kiama was approved in 1880 and construction of the first 23 miles (37 kilometres) commenced the following year, with the section to Hurstville opening on 15 October 1884 and that to Waterfall on 9 March 1886, travelling onto Kiama from 9 November 1887. The Bankstown Line between Sydenham and Belmore opened on 1 February 1895, while a private line opened from Clyde Junction to Rosehill on 17 November 1888 and was extended by another company to Carlingford on 1 August 1901.

In December 1896 the minister appointed the Public Works Committee as a royal commission to examine the best way of extending the railway into the city. It dismissed the need for the conveyance of railway goods traffic into the city but highlighted the requirements for a city railway that would provide scope for a future extension to Circular Quay, a line to the eastern suburbs, a link with the north shore and a future circular railway under the city. [10] The commission also backed a plan for a new city terminal station by Henry Deane, the new Engineer in Chief for Existing Lines, but this would require resumption on 10 acres (four hectares) of Hyde Park, which was strongly opposed by powerful local interests.

Thus, Redfern Station on the outskirts of the city remained the terminus for rapidly increasing number of commuters, who needed to change to steam trams (and electric trams from 1898) for their onward travel to and from their places of work.

The importation of three open saloon carriages from the United States in 1877 brought a revolution in suburban rail travel and on the wider commuter network. Over the years, nine different builders supplied 659 of these popular carriages, which dominated Sydney's suburban scene for over 50 years. [11]

A grand station for the city

The economic depression of the 1890s significantly reduced public works but its impact on rural communities had tipped political power towards the metropolis. In 1895 a new electric tramway was built from Circular Quay to Redfern Railway station, commencing operations in December 1901, while the railway commissioners agitated for an improved city terminal station from 1896.

In early 1897, a royal commission examined the need for a terminal station at Hyde Park. It found it

…expedient the railway system…be extended to the city for the convenience of passengers, and that the best method of doing this is by the route and according to the plan … which would use land in Hyde Park.

The strident opposition of city power-brokers to the loss of 10 acres (4 hectares) of Hyde Park land resulted in the abandonment of the proposal in September 1899. [12]

Edward William O'Sullivan, appointed Minister for Public Works in September 1899, was an enthusiastic champion for railway building and a new grand 'Central Station' for Sydney. Henry Deane and his staff at the Railway Construction Branch of the Public Works Department prepared plans for a new and much larger station, to be built on the site of the Devonshire Street Cemetery.

O'Sullivan established an advisory board to oversee the design and arrangements of the station. Government Architect Walter Liberty Vernon took over responsibility for the design of the new station, assigning the Scottish-born architects Gorrie McLeish Blair and John Barr to prepare designs for the advisory board. Barr's design featured a French Renaissance character, whereas Blair followed the Italian Baroque style. The former was selected to prepare the detailed designs for Sydney's 'Central Station', which is regarded as being in the Federation Academic Classical style. [13]

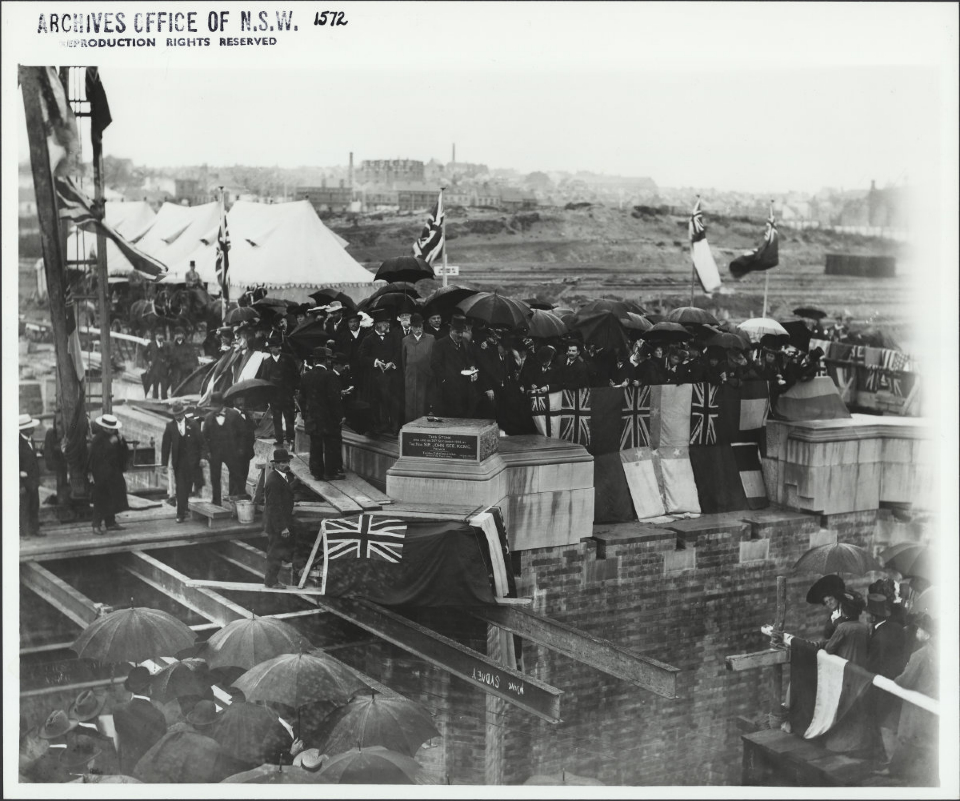

[media]Work on surveying and clearing the site for the new station commenced in 1901. The graves were removed from Devonshire Street Cemetery and the coffins and headstones were loaded onto wagons and hauled by steam trams to a new cemetery at La Perouse.

[media]The station building was constructed in two distinct phases. Edward O'Sullivan laid the foundation stone for the stage one station on 30 April 1902, with a second foundation stone for the tower block being laid by Premier Sir John See on 26 September 1903. The official opening of the phase one station building was on Saturday 4 August 1906. Joseph Carruthers, as Premier and Minister for Railways, opened the grand ticket office and then Charles A Lee, Minister for Public Works, sold the first ticket, blew a golden whistle and waved off the first train from No. 12 platform (of 13 initially provided). [14] In April 1913 two additional tracks (the Bankstown Lines) were constructed and divided into four new terminal platforms numbered 16 to 19.

The Commonwealth Government's Postmaster-General had a grand parcels post office erected immediately to the west of Central Station. Also designed by Gorrie McLeish Blair, this six-storey building was completed in 1913. The parcels post office handled parcels, luggage and on-board provisioning for the trains and was connected to various station platforms (and eventually the Sydney electric platforms) by a series of tunnels in the station basement.

[media]In 1914–15, the Government Architect's Office, now headed by George McRae, drew up plans for stage two of the grand station, again with Gorrie McLeish Blair as the principal architect. The work comprised a new east wing of offices, two new floors of offices and a first floor dining room, as well as a smaller third floor office complex and completion of the clock tower. Construction commenced in August 1915, but wartime shortages slowed progress. The tower clock began operating on 12 March 1921 and the commissioners reported that the world-class station had been completed.

Separating passenger and goods trains

By the early twentieth century the passage of goods trains along Sydney's main lines was disrupting the flow of passenger traffic. With the appointment of Thomas Richard Johnson (from the Great Northern Railway in Britain) as Chief Railway Commissioner in January 1907, there was now a decisive leader prepared to address this issue. Two Standing Committees on Public Works recommended the Glebe Island be developed for upgraded shipping and railway facilities. The Public Works report recommended a double-track goods line from Summer Hill to White Bay and Rozelle with connections to Darling Harbour; a goods line from Wardell Road to connect with the above at Abbotsford and a railway yard to accommodate 5000 goods wagons and 4200 feet of ship's berthing facilities.

The first Metropolitan Goods Line from Flemington to Campsie was officially opened on 11 April 1916 and a the second, from Wardell Road Junction in Dulwich Hill to Glebe Island (Rozelle), opened on on 25 May 1916. The locomotive depot and new 'gravitation' marshalling yards at Enfield, big enough to take 4000 wagons, followed best practice in America and England and were at the heart of the system. The connecting line between Rozelle and Darling Harbour opened on 23 January 1922. [15]

Another component of the metropolitan goods network was the abattoirs branch line north from Pippita, which opened on 31 July 1911, although the State Abattoirs complex did not open until April 1915. [16] The line crossed busy Parramatta Road by an overbridge. Passenger trains carried workers to the abattoirs while goods trains brought in livestock and materials and took out their finished products. Other sidings, such as those at Rozelle, Dulwich Hill and Leichhardt, served the emerging industries in the inner suburbs.

Enhancing goods handling

The loading and unloading of goods onto traditional four-wheel railway wagons was a labour intensive task and the New South Wales Railways had a reputation for delivering goods in damaged condition. Accordingly, improving the efficiency of goods handling technology was an important goal of the Metropolitan Goods Lines initiative.

With ever increasing quantities of grain being grown in the 'wheat belt' on the plains west of the Great Diving Range, the task of transporting it to Darling Harbour in bags and transferring it to ships for export was increasingly seen as inefficient. Despite a detailed report by Dr NA Cobb of the Department of Agriculture for the introduction of bulk handling for wheat in February 1902, there was no action until 1915, when the American firm Metcalf & Company Ltd, offered to act as consulting and designing engineers for the establishment of bulk facilities in four states. New South Wales was the only state to accept the offer and in 1916 the Grain Elevators Act was introduced, providing for the erection of terminal elevators at the Sydney and Newcastle ports, together with up to 200 country silos.

Pyrmont quarry master Robert Saunders was contracted to level Glebe Island and by 1918 the foundations for the grain elevators and silos were being established. [17] The Sydney grain terminal was completed in 1921, but the Newcastle terminal and silos in the northern wheat belt were initially eliminated from the program. [18] While the railway commissioners failed to provide the large bulk grain wagons urged by Metcalf engineers, the equipment that was installed greatly enhanced the efficiency of wheat transport by rail and overcame the large losses of wheat that had occurred at country rail centres due to mice. Transport from farm to country silo still required bagging of wheat and transporting these to the board's silos.

Bradfield's grand vision

[media]In 1908 Charles Wade's Liberal Reform government deflected pressure about urban transport by appointing a royal commission to enquire into improving the City of Sydney. It received submissions from Walter Vernon, who drew examples from London and Paris, and the brilliant young engineer John Job Crew Bradfield, who submitted designs for an underground electrified city railway. The election of the McGowen Labor government in 1910 brought hope for action with its minister for public works, Arthur Hill Griffith, introducing a bill for the underground city loop railway into parliament in 1912. It was condemned by conservative politicians as 'an orgy of extravagance' and was withdrawn. [19]

The resounding election win by Labor under William Holman in December 1913 provided the platform for the party to implement its policies. Bradfield was sent overseas in 1914 to study advances in urban railways, electric traction and long span bridges to link the north shore with the city. He submitted designs for the through-electric station at Central and a three-track underground loop in 1914 and 1915. Bradfield's Central Electric Station was a radical departure from current station design, being derived from North American practice, although the Elizabeth Street entrance featured classic design with Greek Ionic columns.

The outbreak of World War I diverted funds to the war effort and Holman was forced to postpone the city works in June 1916. Construction commenced again in early 1917, only to be halted after scandals led to the cancellation of the contract with Norton Griffith. Over the next 25 years, construction of the City Railway became a start-stop affair, with Labor governments supporting the work and conservatives closing it down.

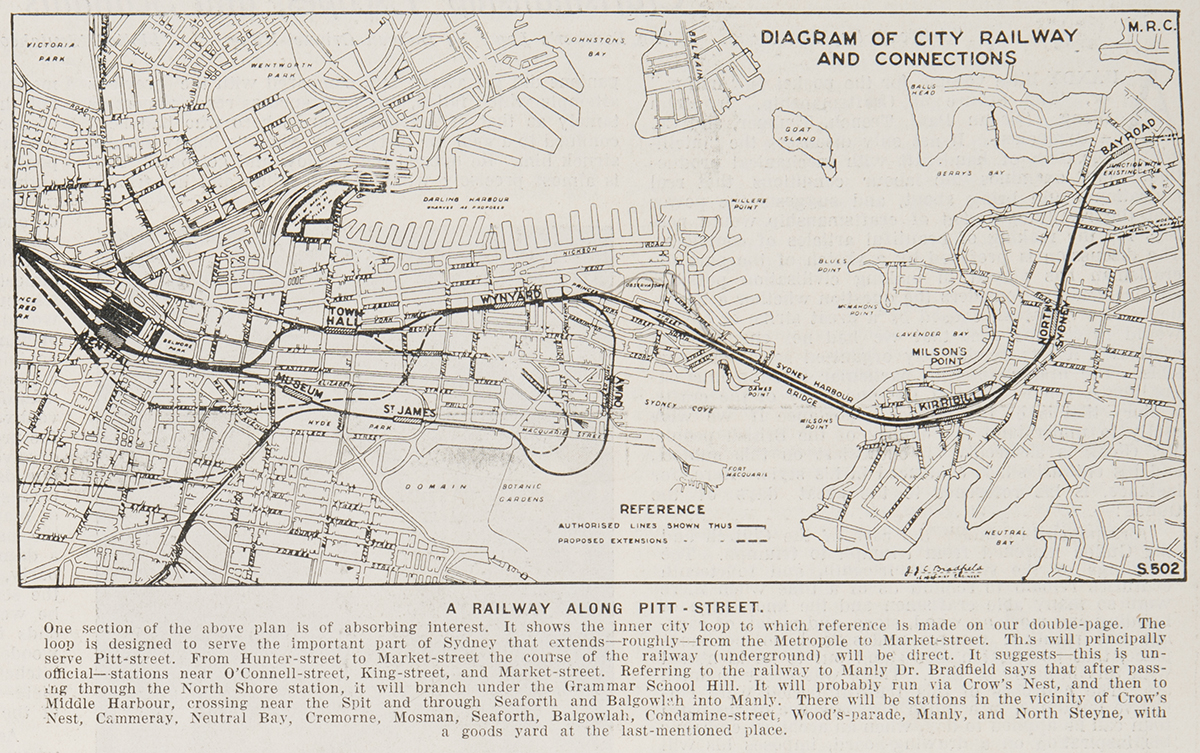

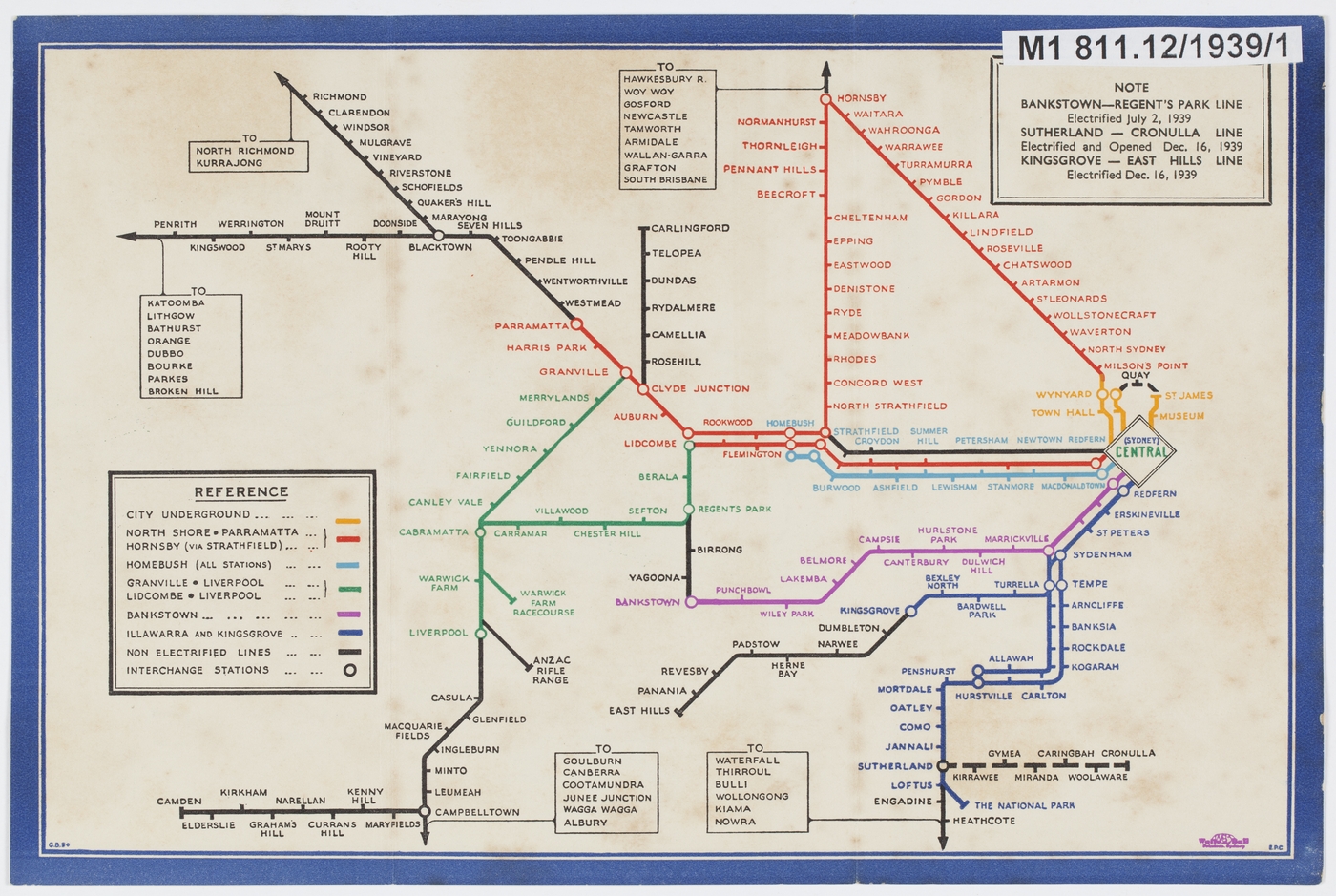

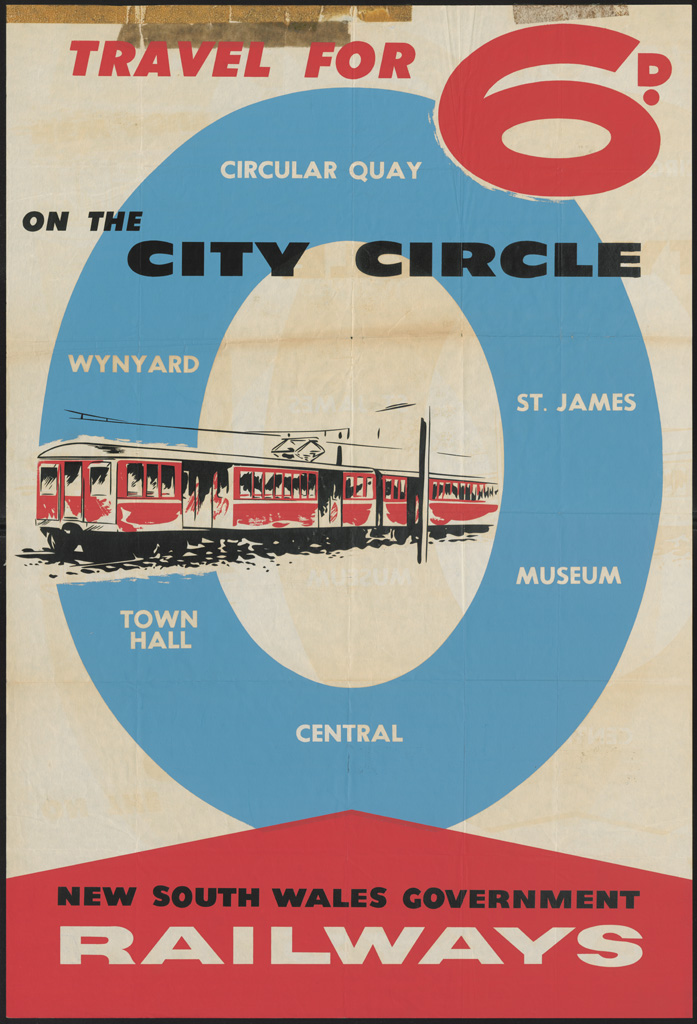

[media]Construction of the City Railway commenced under the Dooley Labor government and received a major boost with the election of the first Lang government in June 1925. New electric trains, built to American designs, were introduced in 1926 and the first service ran from Central Station to Oatley on 1 March 1926. By December that year, electric trains commenced running on the underground section to Museum and St James stations.

[media]The onset of global depression in 1929 led the conservative Bavin to government lay off 1400 construction workers on the project and cancel the Circular Quay section of the City Railway and the Eastern Suburbs line. When Jack Lang won the October 1930 election in a landslide, work on the City Railway and the Harbour Bridge was expanded to create employment, bringing Lang into conflict with the Loan Council. Lang had the satisfaction of overseeing the commencement of electric train services between Central Station and Wynyard on 28 February 1932 and of formally opening the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which linked the North Shore Line with the Sydney suburban network at Wynyard, on 19 March that year, two months before he was dismissed by Governor Philip Game. [20]

[media]The City Railway loop would finally be completed on 22 January 1956 with the opening of Circular Quay station.[media] The Eastern Suburbs Railway, dogged by cycles of start-up and abandonment, finally opened on 23 June 1979.

Sydney's Olympic Games in 2000 brought new investment in suburban railways. A new electric line and high-capacity station serving the Olympic Park and other facilities at Homebush opened on 8 March 1988 while the 10 kilometre underground Airport Line from Central to Wolli Creek (on the East Hills Line) opened on 21 May 2000. [21] The Carr government announced a proposal for a rail link from Chatswood to Parramatta. Construction of the underground Chatswood to Epping section commenced in November 2002 with intermediate stations at North Ryde, Macquarie Park and Macquarie University serving industrial, commercial and educational centres. The line opened on 22 February 2009.

Commuter trains

In the post-World War II suburban settlement expanded beyond the metropolitan area to the Blue Mountains, Central Coast, Southern Highlands and the Illawarra. The Western Line was electrified to Bowenfels by June 1957, as was the Short North to Gosford, on 24 January 1960. These areas were served by new electric trains for commuters and traditional carriage stock hauled by electric locomotives. Sydney's first double-deck electric train commenced service on 6 January 1969, with this design becoming standard for the Sydney suburban fleet. The first double-deck long-distance commuter trains commenced running to Gosford in June 1970.

The Wran government extended the northern electrification to Newcastle on 3 June 1983, and on the Illawarra Line to Wollongong on 4 February 1986 (extended to Kiama on 17 November 2001).

Further reading

Collins, Ian. 'The country interest' in Wotherspoon, Garry, ed. Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History. Sydney, Hale & Iremonger, 1983.

David Cooke, et al. Coaching Stock of the NSW Railways: Volume 2. Matraville: Eveleigh Press, 2003.

Fitzgerald, Shirley and Golder, Hilary. Pyrmont and Ultimo Under Siege. Ultimo: Halstead Press, 2009.

Grain Elevators Board of New South Wales. 50 Years of Bulk Grain Handling in NSW. Sydney: Grain Elevators Board of NSW, 1972.

Hagarty, Donald. The Building of the Sydney Railway: The known story of the work of six men – a naval surveyor, four engineers and the contractor who, with many others, built the first railway from Sydney to Parramatta 1848–1857. Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2005.

Heritage Group, State Projects. Central Station Conservation Management Plan. Sydney: NSW Department of Public Works and Services, 1995.

Lee, Robert. Colonial Engineer: John Whitton 1819–1898 and the Building of Australia's Railways. Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2000.

McKillop, Robert, Ellsmore, Donald and Oakes, John. A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006. Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008.

Pollard, Neville. 'City meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines'. Australian Railway History 67, no 942 (April 2016).

Pollard, Neville. 'The Story of the Abattoirs Line'. Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin 36, no 571–2 (May–June 1985).

Report of the Royal Commission on City Railway Extension 1897. NSW Parliamentary Papers 4, 1897.

Singleton CC. 'History of the Sydney Railway Station, Part II'. AR&LHS Bulletin 50, December 1941.

Notes

[1] D Hagarty, The Building of the Sydney Railway: the known story of the work of six men - a naval surveyor, four engineers, and the contractor who, with many others, built the first railway from Sydney to Parramatta 1848–1857 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2005), 34

[2] D Hagarty, The Building of the Sydney Railway : the known story of the work of six men - a naval surveyor, four engineers, and the contractor who, with many others, built the first railway from Sydney to Parramatta 1848–1857 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2005), 32–41

[3] D Hagarty, The Building of the Sydney Railway : the known story of the work of six men - a naval surveyor, four engineers, and the contractor who, with many others, built the first railway from Sydney to Parramatta 1848–1857 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2005), 197

[4] R Lee, Colonial Engineer: John Whitton 1819–1898 and the Building of Australia's Railways (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2000), 116

[5] R Lee, Colonial Engineer: John Whitton 1819–1898 and the Building of Australia's Railways (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2000), 217

[6] Heritage Group, State Projects, Central Station Conservation Management Plan (Sydney: NSW Department of Public Works and Services, 1995), 46

[7] CC Singleton, 'History of the Sydney Railway Station, Part II', AR&LHS Bulletin, no 50 (December 1941): 73

[8] Australian Railway Historical Society Railway Records Centre, Charles Oliver Collection, official menu, 'Celebrating the Joining of the Southern & Northern Systems of NSW Railways'

[9] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 13

[10] Report of the Royal Commission on City Railway Extension 1897, NSW Parliamentary Papers 4 (1897): 20

[11] D Cooke, et al, Coaching Stock of the NSW Railways: Volume 2 (Matraville: Eveleigh Press, 2003), 10–11, 13–15, 30–79

[12] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 27–28

[13] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 23–24

[14] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 36

[15] N Pollard, 'City Meets Country: Centenary of the Metropolitan Goods Lines', Australian Railway History, 67, no 942 (April 2016): 22

[16] Neville Pollard, 'The Story of the Abattoirs Line', Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, 36, no 571–2 (May–June 1985): 78

[17] S Fitzgerald and H Golder, Pyrmont and Ultimo Under Siege (Ultimo: Halstead Press, 2009), 88

[18] Grain Elevators Board of New South Wales, 50 Years of Bulk Grain Handling in NSW (Sydney: Grain Elevators Board of NSW, 1972), 9

[19] I Collins, 'The Country Interest' in G Wotherspoon, ed, Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983), 122

[20] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 49–53, 55–58

[21] R McKillop, D Ellsmore and J Oakes, A Century of Central: Sydney's Central Station 1906 to 2006 (Sydney: Australian Railway Historical Society, 2008), 104, 122

.