The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Colonial Hospital

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Colonial Hospital

[media]The Colonial Hospital was Parramatta's third and final hospital dedicated to convict healthcare. Commencing in 1818, this Macquarie-era hospital operated for the next 30 years on the site of the previous two hospitals until it became the public Parramatta District Hospital in 1848. Today the area in which these early hospitals were located is called the Parramatta Justice Precinct, but the Heritage Courtyard at the Justice Precinct offices on Marsden Street commemorates the site's earlier role as the Hospital Precinct by offering the public a glimpse into its two hundred year history of continuous medical care.

Early history of the site

Between 10,000 and potentially 22,000 years before European settlement, [1] Parramatta was the traditional hunting and fishing grounds of the Darug-speaking Burramatta people. Located on the bank of the Parramatta River, the land of the Parramatta Hospital site would have been used by the Burramatta at least sporadically for fishing and camping purposes. [2]

From 1789 to 1818, Parramatta's first two hospitals, collectively dubbed the General Hospital, were located here. These hospitals suffered from poor design and construction and were ill-equipped in both size and resources to serve the considerable healthcare needs of the ever-increasing penal colony. In fact, Richard Rouse complained that the second of these hospitals was 'so dirty and the smell so offensive that I could hardly ever go in,' [3] adding that the convicts were 'carried there often against their will.' [4] Governor Macquarie, who was determined to improve public buildings while in office, concurred with Rouse but further accounted for the hospital's problems by referring to its surgeon in charge in 1813, Edward Luttrell, as 'sordid and unfeeling' to those under his care and generally negligent in 'the discharge of his public duties,' leaving the hospital unhygienic and unregulated. [5]

Parramatta's third hospital, 1818–1848

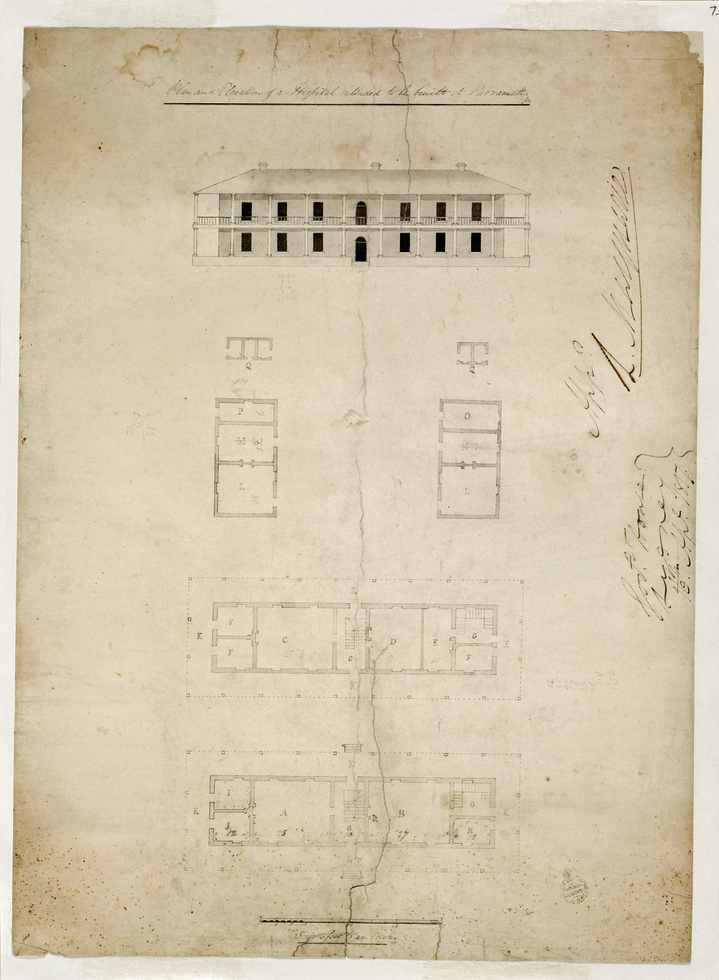

[media]At Macquarie's request, John Watts designed a new hospital for the site. On 16 April 1817, Macquarie approved Watts's design for a two-storey brick building with 'an upper and lower verandah all round.' The main hospital building was to contain slender timber columns and 'all the necessary out offices for the residence and occupation of 100 patients, with ground for a garden and for the patients to take air and exercise in,' as well as a 'high strong stockade' to enclose the premises. [6]

By August 1817 construction was underway with Rouse acting as overseer and by September the following year the hospital was completed. It contained two wards and outbuildings including two morgues, washrooms, a kitchen and privies. [7] Brick portions of the hospital's privy system dating back to this period have been partially excavated and can be viewed in situ today at the Heritage Courtyard located on the old hospital site at 160 Marsden Street. [8] Pavers containing facts about archaeological excavations in the courtyard also mark the spots where footing trenches for the walls of the 1818 kitchen outbuilding stood, as well as the location of the hospital's 1844 stone boundary wall which replaced the original timber stockade, [9] and where a deep well and cistern that supplied the Colonial Hospital's laundry and cookhouse with water in the 1820s were discovered. [10]

The main hospital's wall footings are also displayed in situ at the courtyard and contain flat sandstock bricks with rare double arrow markings, likely made at The Crescent in Parramatta Park or at Brickfield Street. [11] While the broad arrow was indicative of convict-made bricks and therefore, government ownership, the archaeologists responsible for the site's excavation assert that the double arrow marking is isolated to this site in Parramatta, potentially as a way of showing that these bricks were specifically intended for the hospital building. [12] During the 2006 excavations, archaeologists also uncovered a pit from the 1818 hospital era containing animal bones, an amputated human hand and smoking pipes. [13]

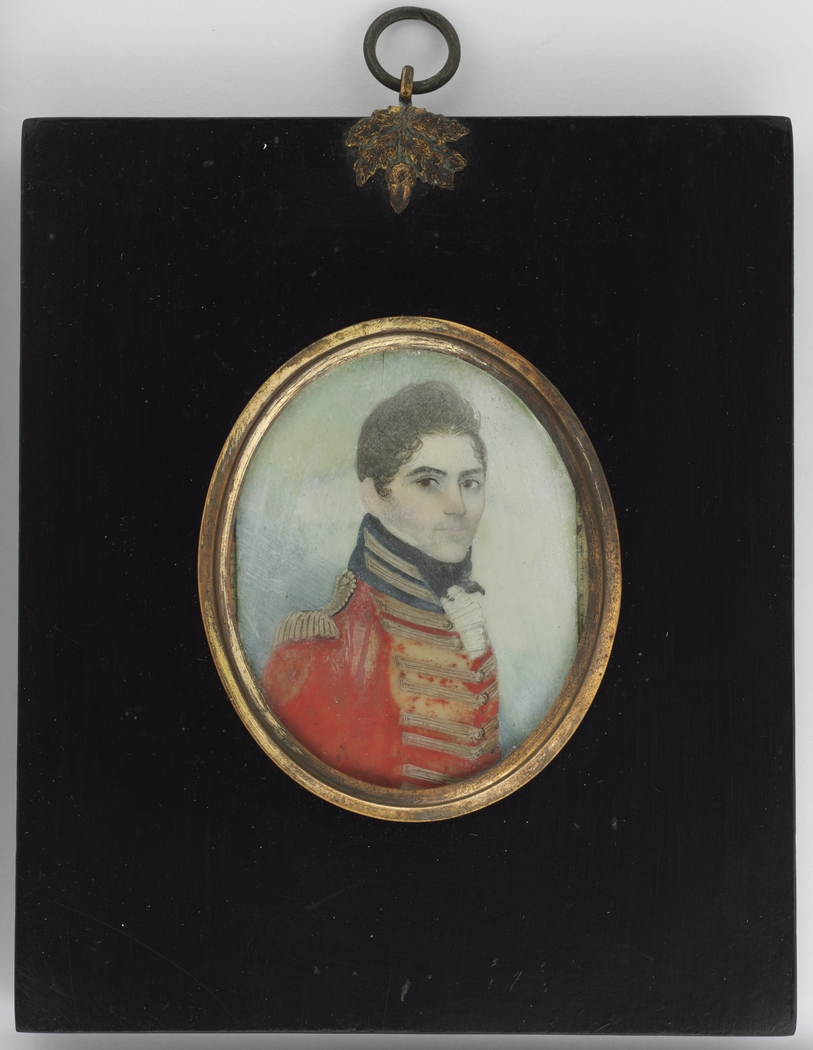

[media]The new hospital was far from ideal. When designing the hospital, Watts neglected to consult Major West, who was appointed Parramatta's surgeon in charge in August 1815 (a position West held until July 1821). Instead, Watts based his design solely on the military hospital he had previously designed at Sydney. Consequently, male and female patients were not separated and the building that was supposed to accommodate 100 patients could, in reality, only accommodate 50. Epidemics, such as the typhus fever that affected the convict population in winter 1819, [14] influenza, mumps and whooping cough outbreaks in the 1820s, [15] seriously tested the limits of what should have been the new and improved hospital. At the best of times, the hospital also had to contend with the constant problem of dysentery, which claimed the lives of over half the convicts admitted, [16] as well as tuberculosis or 'consumption,' scurvy, oedema (also known as 'dropsy'), arthritis and an eye condition that caused blindness when the inflammation was left untreated. [17] Unsurprisingly, syphilis was prevalent enough in the convict population for Principal Surgeon D'Arcy Wentworth to have told Commissioner Bigge that, in the absence of doors and locks, the common knowledge that female patients were all syphilitics served as the hospital's only security against the wider male population. [18]

The poor sanitation and generally malodorous state of the earlier hospitals also proved to be an ongoing problem. In 1820, for example, surgeon William Redfern complained about the 'large dung heap collected behind the hospital.' [19] The dung heap, Redfern believed, had been 'accumulating there since the building was first opened' two years prior and 'the effusia from it is very injurious and at times almost intolerable when the sea breeze blows it into the wards...' [20]

The Parramatta surgeons

[media]When West moved to Windsor Hospital in 1821, Henry Grattan Douglass was put in charge of the Colonial Hospital. Macquarie stipulated that a new surgeon's residence was to be built for Douglass and his family on the hospital site. The new surgeon's residence, built in the early eighteenth century English Palladian style that Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth preferred, replaced what Macquarie considered to be the dilapidated 'almost uninhabitable' 'barrack' West had presumably endured previously. [21] Thomas Berdmore Allen succeeded Douglass and, upon Allen's transfer to Windsor Hospital in 1826, Matthew Anderson filled the position of surgeon at Parramatta until his retirement in 1838. The Anderson Fountain, which once stood in Centenary Square (also known as Parramatta Square) and is currently located in the northwest corner of Prince Alfred Park, was constructed with funds bequeathed by Anderson for this specific purpose. Anderson had frequently campaigned on public health issues and particularly lobbied for the public availability of fresh water as a preventative for disease, [22] undoubtedly because unclean drinking water was considered a major cause of the dysentery that afflicted so many of his patients. [23]

The cost of treatment

Originally, settlers had been entitled to send their sick and injured convict servants to the hospital at the government's expense. By the end of Ralph Darling's governorship, however, settlers were expected to pay for their servants' hospital treatment. Free settlers were also expected to pay for their own treatment at the convict hospitals. By contrast, government employees, including the military and their families and servants, were treated without charge, as were any free paupers and Aboriginal people who could supply a signed certificate from a clergyman or magistrate confirming their lack of funds, although Aboriginal and pauper emergency cases were admitted at the surgeon's discretion. [24]

A period of transition

With an ageing convict population, sick and elderly paupers were a growing problem in the colony, but at the same time the decrease in transportation ships in the 1830s, and the complete cessation of the convict system in 1841, led the government to make preparations for the closure of its colonial hospitals. [25] In the meantime, while Governor Gipps preferred that the convict hospitals be reserved for convicts only, he recognised that in the absence of designated pauper hospitals there was nowhere else for the free poor to seek treatment. [26] As the decade of the 1840s wore on, institutions catering for elderly and infirm ex-convicts who could not support themselves were established and convict hospitals were once more deemed strictly for the treatment of the few remaining convicts. [27] Typically, earlier government institutions that were no longer relevant were reassigned as asylums. The Female Factory, for example, became Parramatta's Asylum for Invalid and Lunatic Convicts.

The closure of Parramatta's Colonial Hospital was considered as early as 1843 [28] but another five years passed before the convict hospital was closed on 31 March 1848. [29] Parramatta locals who wanted the hospital to henceforth serve the community as a public hospital petitioned the governor who granted their request on 6 May 1848. [30]

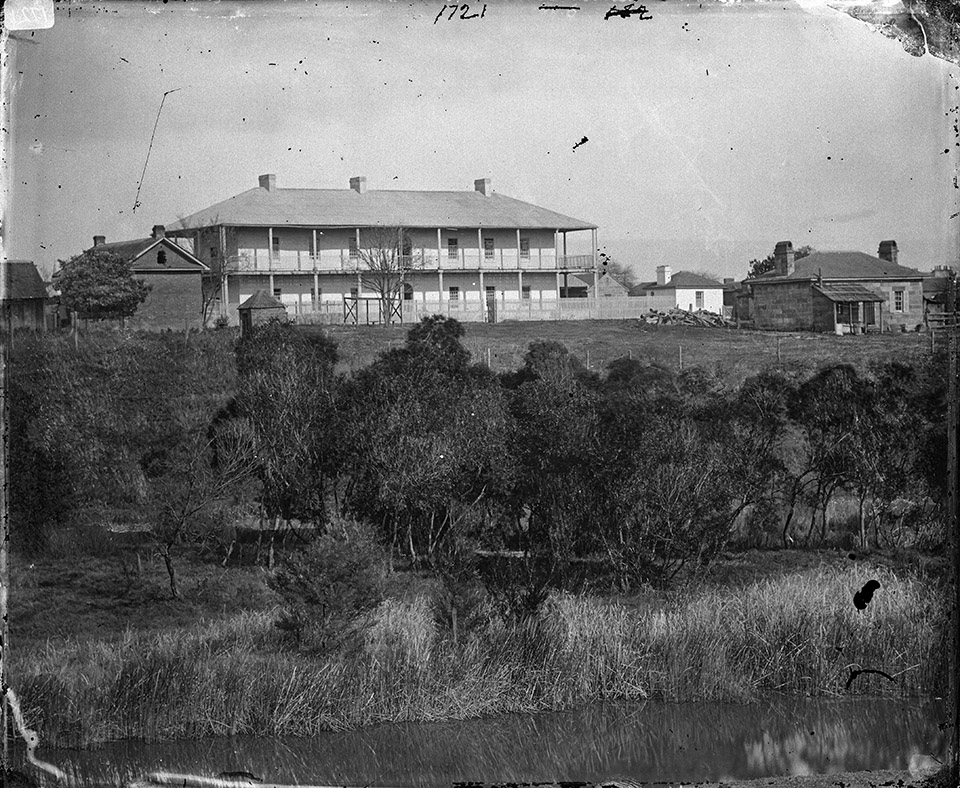

The official closing of the Colonial Hospital in March 1848, and its reopening as the public Parramatta District Hospital in June – partially funded by the government, private contributions and patient fees [31] – brought to an end an era of convict health care that all began in a tent hospital by the Parramatta riverside in 1789. [media]But it would be decades before sufficient funds were available for the public hospital to completely shed its former convict visage of barred windows and to acquire newly painted walls, decorative garden tiles and welcoming flower-filled gardens.

References

Casey, Mary and Tony Lowe, Reports Relating to the Excavation of the Former Parramatta Hospital Site. Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, March 2006. http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/reptpjp.htm. Viewed 8 January 2015.

Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW). Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital. Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988.

Kass, Terry, Carol Liston and John McClymont. Parramatta: A Past Revealed. Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996.

Notes

[1] 10,000 plus years is the conservative date but use of this land for hunting and fishing could easily date back 15,000 to 22,000 years when taking into account the archaeological evidence of Aboriginal presence discovered in 2004–05 during excavations of 109–113 George Street; the eastern end of the street on which the Parramatta Hospital site is located. According to Casey and Lowe, 'Recent archaeological work at the eastern end of George Street indicates the presence of Aboriginal people in Parramatta as extending back 15,000 to 22,000 years BP. The 109–113 George Street site is the oldest known archaeological site revealing Aboriginal presence in the Sydney region indicating the known location of Aboriginal existence prior to stabilisation of post-glacial sea levels c.6000 years ago.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation' (Marickville, NSW: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006) 51, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[2] Dr Laila Haglund's testing of the Parramatta Children's Court site for potential Aboriginal archaeology unearthed only limited Aboriginal artefact remains. Haglund concluded that 'Aboriginal heritage material was in early colonial times present on and/or in the surface sediments of the site but probably as occasional small scatters, and 'It is likely that the area was not intensively used in pre-colonial times or that evidence of earlier, more intensive use had been removed well before this time by natural events such as erosion or floods.' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Parramatta Children's Court Site: Results of the Archaeological Investigation' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 2006), 51, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pcc/pccs3.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015. Archaeological remains may also have been disturbed by nineteenth and twentieth century occupation and hospital construction activities. Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Results Archaeological Investigation Stage 2c: Parramatta Justice Precinct former Parramatta Hospital Site (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September, 2006), 2, 8, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015; Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Archaeological Excavation: Parramatta Justice Precinct, Former Parramatta Hospital Site, George and Marsden streets, Parramatta (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, April 2005), 1, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/leaflet2.pdf, viewed 6 January 2015

[3] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 17; Evidence of Richard Rouse, 19 September 1820, in JT Bigge, Report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Colony of New South Wales (Great Britain: Parliament, House of Commons, 1822), appendix; Bonwick Transcripts, Box 1, 329–332, Mitchell Library, Sydney; Rebecca Catherine Ruth Geraghty 'A Change in Circumstance: Individual Responses to Colonial Life' (Honours Thesis, University of Sydney, 2006), 34, http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/2190/3/GeraghtyRebecca.pdf, viewed 16 March 2015. Note that some signage displayed near the site incorrectly attributes this quotation to Governor Macquarie.

[4] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988)17; Evidence of Richard Rouse, 19 September 1820, Bonwick Transcripts, Box 1, 329–332, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales; Rebecca Catherine Ruth Geraghty, 'A Change in Circumstance: Individual Responses to Colonial Life' (Honours Thesis, University of Sydney, 2006), 34 http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/2190/3/GeraghtyRebecca.pdf, viewed 16 March 2015. Note that some signage displayed near the site incorrectly attributes this quotation to Governor Macquarie.

[5] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 17

[6] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 19

[7] Terry Kass, Carol Liston and John McClymont, Parramatta: A Past Revealed (Parramatta: Parramatta City Council, 1996), 87

[8] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 2 Final' (Marrickville, NSW: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September 2006) 38, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart2.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[9] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 2 Final' (Marrickville, NSW: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September 2006), 38–9, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart2.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[10] Images of the well and cistern can be found in Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 1 Final' (Marrickville, NSW: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September 2006), 22 http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015. The well is Photo 2–17 and the cistern is Photo 2–18.

[11] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 1 Final' (Marrickville, NSW: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, September 2006), 20 http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[12] 'Convict Arrow Bricks,' Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/find_arrow_bricks.htm, viewed 19 March 2015

[13] Mary Casey and Tony Lowe, 'Preliminary Excavation Report, Stage 2c Part 1 Final' (Marrickville: Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, 21, 26 (contains photo), 27 (contains photos) http://www.caseyandlowe.com.au/pdf/pjp/pjpstage2cpart1.pdf, viewed 19 March 2015

[14] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 19

[15] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 22

[16] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 22

[17] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 19, 22

[18] Evidence of D'Arcy Wentworth, nd 1820, in JT Bigge, Report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Colony of New South Wales (Great Britain: Parliament, House of Commons, 1822) appendix; Bonwick Transcripts, Box 6, 2510–31, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales; Rebecca Catherine Ruth Geraghty, 'A Change in Circumstance: Individual Responses to Colonial Life' (Sydney, University of Sydney, 2006), 34 http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/2190/3/GeraghtyRebecca.pdf, viewed 16 March 2015

[19] Evidence of William Redfern, in JT Bigge, Report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Colony of New South Wales (Great Britain: Parliament, House of Commons, 1822), Bonwick Transcripts, Box 26, 6215–19, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[20] Evidence of William Redfern, in JT Bigge, Report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Colony of New South Wales (Great Britain: Parliament, House of Commons, 1822), Bonwick Transcripts, Box 26, 6215–19, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[21] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital, (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 21

[22] 'The Anderson Fountain, Parramatta - A Surgeon's Gift,' Parramatta Heritage Centre, http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/06/04/the-anderson-fountain-a-surgeons-gift/, viewed 18 March 2015

[23] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988), 19

[24] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 22, 24

[25] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 24

[26] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 25

[27] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 25

[28] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 22

[29] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 30

[30] Cumberland Area Health Service (NSW), Caring for Convicts and the Community: A History of Parramatta Hospital (Westmead: Cumberland Area Health Service, 1988) 30

[31] This information is displayed in the pavilion windows at the Heritage Courtyard, Justice Precinct Offices for the NSW Attorney General's Department, 160 Marsden Street Parramatta.

.