The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Rickards, Kate

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Rickards, Kate

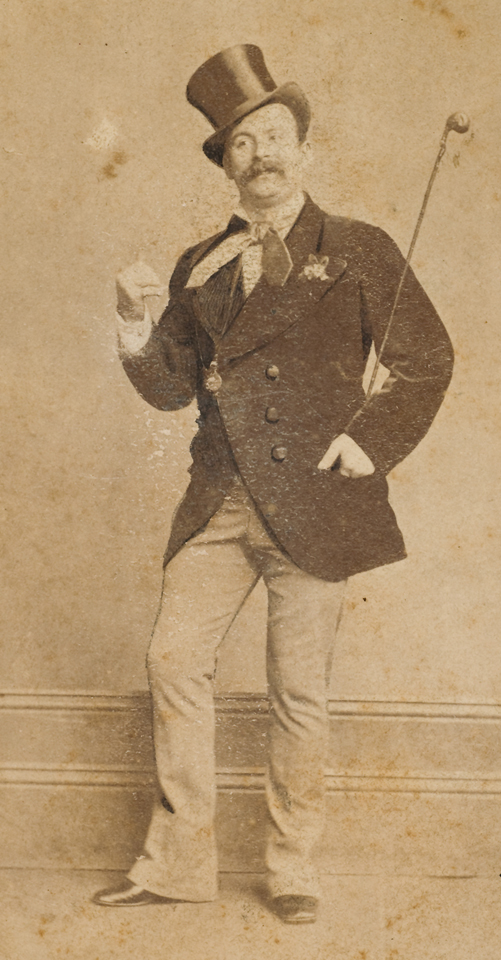

Kate Rickards, also [media]known as Kate Leete, Kate Rickards-Leete, Katie Rickards and Katie Angell, was an Australian gymnast, trapeze artist, vaudeville performer and costume designer best known for her work on the Tivoli circuit owned by her husband, the Cockney comic and theatrical entrepreneur, Harry Rickards.

Early life and career

Born Kate Roscow in Melbourne, on 8 December c1862, she was the daughter of a publican, William Roscow, and is thought to have spent some of her childhood years in Nelson, New Zealand. [1] As Katie Angell, she began her stage career at the age of 11 when she was apprenticed to Lottie D'Aste and Victor Angell of the British Royal Magnet Troupe. The Royal Magnet Troupe promoted Katie as 'the youngest and most beautiful trapeze performer in the world'. [2] Following her performance on the double trapeze with Lottie D'Aste during their second Brisbane School of Arts season in 1873, the Brisbane Courier noted:

The petite debutante must certainly be congratulated on her first appearance, and Lottie had better look to her laurels, which bid fair to be disputed by her 'little sister'. [3]

Both Katie and Lottie received similarly favourable reviews for the duration of the troupe's Australian tour. The following year, Lottie's husband Victor Angell died tragically by drowning when the troupe was in Queensland. [4] Despite their loss, Lottie and Katie continued to perform.

[media]By August, 1874, the Royal Magnet Troupe was in San Francisco, where Harry Rickards, still married to his first wife but smitten with Lottie, took over as manager and toured them across the United States. Katie, then 12 or 13, travelled with the troupe by rail in cold and uncomfortable conditions to New York. As the Rickards Combination the performers opened at Josh Hart's Theatre Comique, the city's most popular variety hall, in February 1875.

Harry Rickards accompanied the troupe back to London. They toured England in 1876 and around this time Katie Angell also used the stage name of Mademoiselle Katrini. The gymnasts received rave reviews for their daring and expertise. Harry Rickards's biographer Gae Anderson has suggested that the popularity of Lottie D'Aste and the Angells had a positive impact on Rickards's career. [5]

The troupe soon set off on a world tour with the first stop in South Africa. Katie was billed as 'Mademoiselle Katrini, the flying fairy and empress of the air'. [6] This tour was cut short due to apprehension about impending war and they returned to England in 1877. In 1878 Lottie, by then Harry Rickards's lover, died suddenly after a brief illness.

Katie, although affected by Lottie's death, continued to perform and Harry Rickards continued to tour the troupe. When Rickards discovered that two other performers were using the names of Katie and Victor Angell, Katie suggested that she change her name, as an alternative to Harry's plan of legal action. Katie was thereafter billed as Mademoiselle Zenoni, after the Italian prima donna, Margherita Zenoni. [7] Rickards also gave her star billing as 'The Premier Lady Gymnast of the World'. [8]

Becoming Mrs Rickards

Harry and Katie eventually formed a relationship and, on 23 December 1879, their first child, Noni, was born. Around this time Harry had begun to call Katie 'Kate'. They had married on 24 November 1880 in the registry office at Chorlton, Manchester. Kate was 17 and Harry 36. After her marriage, Kate took her husband's family name of Leete as her stage name. Two more children followed: Sydney Stokes Rickards, born 21 September 1883, and Madge Adelaide Rickards on 21 May 1885.

[media]The 'Rickards-Leete Combination' toured Australasia in 1885–86 and Kate made a career change from gymnast to singer and dancer. Her first performance was in the role of Miss Maud Tomkins, a dignified heiress, in Garnet Walch's Eccentricity, (later Bric-a-Brac).

Back in England, on 28 April 1887, Kate gave birth to another daughter, Edith, who died in September of the same year. Harry and Kate decided to return to Australia indefinitely for the sake of the remaining children's health. The family arrived in Adelaide in 1888.

In the same year, the Rickards-Leete Combination performed in Melbourne, where Kate was criticised for singing a song with references to the Queen. [9] The Rickardses took heed of emerging republican sentiments and modified their repertoire accordingly.

[media]One of Kate's most important stage roles was that of Tootsie Sloper, in The Land Lubber: a nautical nightmare. The farcical comedy was written especially for Kate by Garnet Walch and was first performed at Melbourne's Gaiety Theatre after she'd been absent from the stage due to a serious illness. The musical is set in Admiral Blazer's house on Scarborough Beach and on the deck of the yacht, Tootsie. Harry Rickards played Bertie Bobolink, a land lubber in love with Tootsie Sloper, whose family were all sailors. Tootsie declares that no man who cannot prove himself a sailor shall ever become her husband. When The Land Lubber was performed in New Zealand, the Auckland Star attributed its success to Kate:

her song was very good and in the sparkling repartee with which the little piece fairly sparkles she is brilliant. Miss Rickards has fully established herself as a popular favourite in Auckland. [10]

The versatile Miss Rickards played another minor, male role (Charles) in the same play. [11]

In 1892 the Rickards family made Sydney their headquarters. At the opening night show, in May, Kate and daughter Noni were two of the six women who performed the hit of the evening, 'The Ta-Ra-Ra Lament', a song that bemoaned the depravity of the popular but boisterous song, 'Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay'. Eventually all participants surrendered, cavorting wildly around the stage to triple encores. [12]

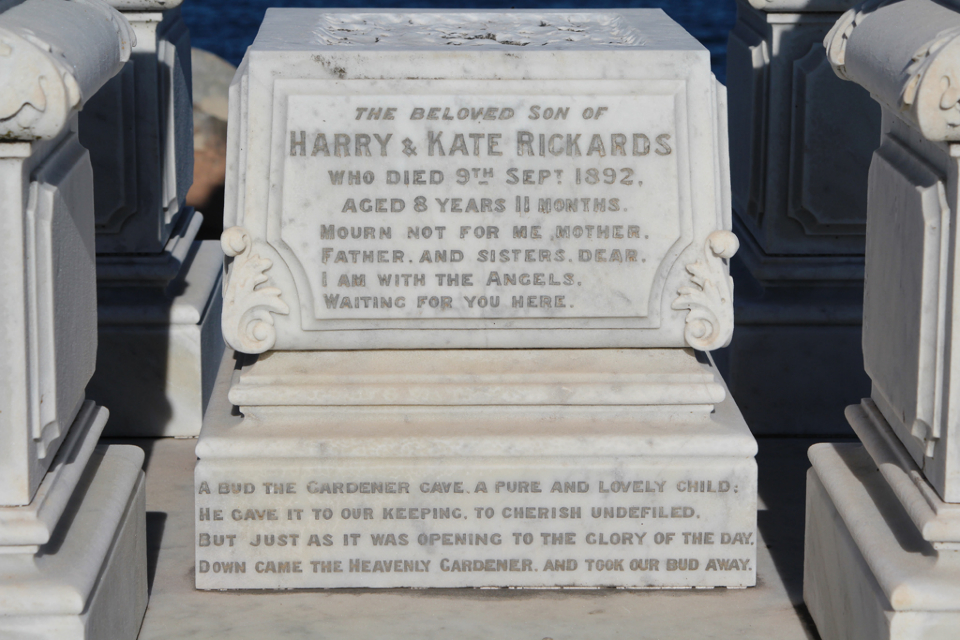

[media]In September of the same year, Sydney Rickards (Leete), aged eight, died suddenly of scarlet fever in Sydney while his parents were on tour in Melbourne. [13]

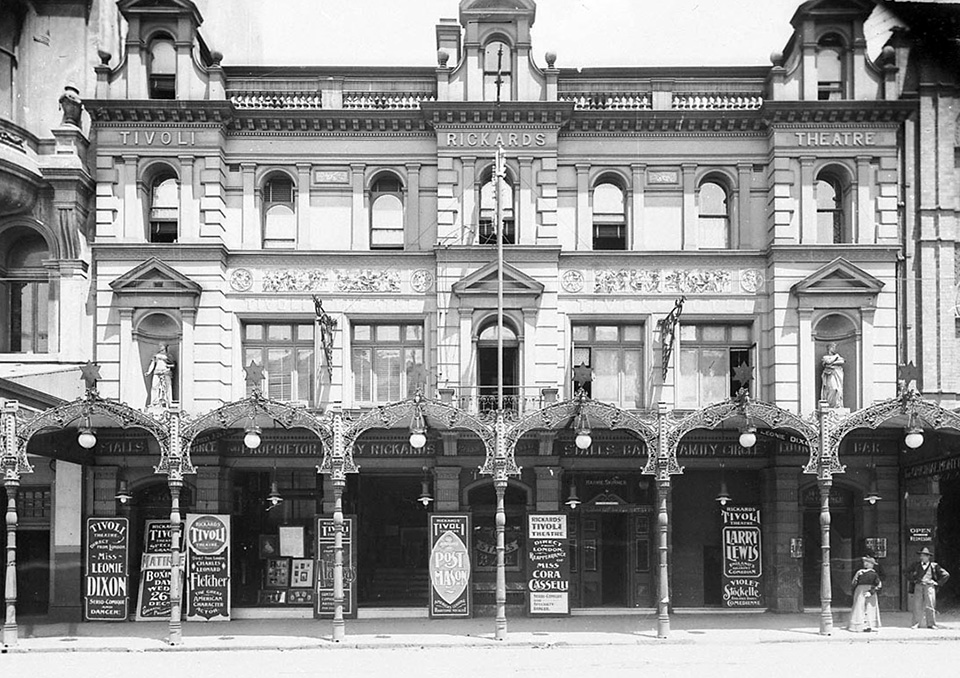

[media]When the rent on the Opera House on the corner of King Street was raised, it was on Kate's advice that Harry leased the Garrick Theatre in Sydney and renamed it the Tivoli. [14] Both Harry and Kate took part in performances; Katie introducing Daisy Bell, inspired by the popularity of bicycling. [15] The Tivoli theatre and circuit were outstandingly successful and Harry Rickards became known as Australia's king of vaudeville. Around this time the family lived in Canonbury, [16] a rented house in Allison Road (now Alison Road), Randwick, where on Sundays they regularly entertained company members and friends.

Life after the stage

In January 1894, Kate retired from the stage to concentrate on costume design for her husband's productions. With help from some London theatrical costumiers and assistants in Sydney, Kate designed costumes for the Rickardses' first foray into pantomime, Jack the Giant-Killer; or, Harlequin Fee Fi Fo Fum, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table at the Theatre Royal. [17] She was also credited with designing costumes for The Gypsy Revels at the Prince of Wales Opera Theatre in Melbourne in 1895 [18] and The Carnival at the Tivoli in 1901. [19]

Around 1905, the Rickards family moved into another house called Canonbury, a grand mansion that Harry had built at Darling Point.

Kate continued work at the Tivoli after retiring from professional life, hosting events such as receptions for visiting celebrities.

Kate Rickards was known for her generosity. In Frank Van Straten's book, Tivoli, there is an anecdote from Percy Crawford describing her sitting in a box at Tivoli shows while the comic Irving Sales, of whom she was very fond, would negotiate loans from the stage with her using hand signals.

[media]After Harry Rickards died in 1911, Kate visited Waverley Cemetery every Sunday and placed fresh flowers on her husband's grave, delegating the duty to someone else when she was not in Sydney. [20] She also commissioned sculptor James White to produce three more busts of Harry in addition to the one that was centrepiece of White’s Rickards memorial. [21] In 1914 a bust of Harry was placed in the foyers of the Tivoli theatres in Sydney and Melbourne. Kate kept the third portrait bust of Harry for her home. [22] The bust in the Waverley cemetery memorial was removed by the family following vandalism c1990.

Kate and her daughters inherited an estate valued for probate at over £135,000 in Australia and £10,000 in England. After her husband's death, she involved herself in the Crown Street Women's Hospital and continued the Rickards tradition of hosting Christmas dinners for the poor in the basement of the Sydney Town Hall. She was reported to have sometimes provided financial assistance to those attendees whom she found to be in particular distress. [23]

In 1921, Kate suffered the additional loss of her daughter, Noni, also an actress.

In September 1922, following a visit to England, Kate Rickards died on board the RMS Ormonde while crossing the Red Sea. As well as providing for her family, she left £100 to each of her servants.

Obituaries praised Kate Rickards not only for her contribution to theatre but also for her kind and generous spirit, her philanthropy and her love of animals. She reputedly kept a 'fine assortment' of dogs at Canonbury, rescued strays and supported every association for the protection of animals.

[media]A commemorative plaque to Kate Rickards sits on the ocean side of the Rickards memorial in Sydney's Waverley Cemetery.

References

Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009

Notes

[1] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 68

[2] Brisbane Courier, 11 September, 1873, p 1

[3] Brisbane Courier, 18 September, 1873, p 2

[4] Queenslander, 11 April 1874, p 11

[5] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 77

[6] Cape Times, 17 March 1877, p 2, quoted in Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 79

[7] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 84

[8] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 84

[9] Argus, 9 July 1888, p 8

[10] Auckland Star, 12 December 1889, p 10

[11] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 167

[12] Frank Van Straten, Tivoli, Lothian, South Melbourne, 2003, p 8

[13] 'In Memoriam', Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September 1898, p 1; NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, registered under Leete, Sidney.

[14] Rutledge, Martha, 'Rickards, Harry (1843–1911)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 11, 1988, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rickards-harry-8207/text14359, viewed 4 September 2012.

[15] Frank Van Straten, Tivoli, Lothian, South Melbourne, 2003, p 8

[16] Not to be confused with Canonbury at Darling Point, built by Harry in 1905.

[17] Gae Anderson, Tivoli King: life of Harry Rickards, vaudeville showman, Allambie Press, Kensington NSW, 2009, p 218

[18] Frank Van Straten, Tivoli, Lothian, South Melbourne, 2003

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 October, 1901

[20] Perth Sunday Times, 8 October 1922, p 31

[21] Conversation with Martin Forest-Reid, Waverley Cemetery, 04/02/2013

[22] The Argus, Melbourne, 16 April 1914, p10

[23] Perth Sunday Times, 8 October 1922, p 31

.