The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Prisons to 1920

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Prisons to 1920

Crime and its punishment in Sydney have never been considered a respectable topic. 'Out of mind, out of sight' was the catchcry. Small justice was shown and little pity. Sympathy for the violators of the law did not seem to exist. The belief that villains should be severely punished seemed universal. Hanging over Sydney's underworld for nearly two centuries was the shadow of the death penalty.

Beginnings

In the 1830s, a person walking south along George Street's western side from Kings Wharf would come upon His Majesty's Gaol on the corner of Essex Street. Here, prisoners were confined before and after trial. Public hangings were commonplace outside its walls, attracting a rowdy mob. The world of the gaol was unforgiving.

The building was made of logs and then rebuilt by convict labour in sandstone. As soon as it was opened, lack of security, poor sanitation and overcrowding prevailed. Cramped conditions persisted. At the same time, there was a gaol in Parramatta with similar problems.

Domestic prisons in Sydney began when in 1796 Governor John Hunter ordered the erection of the two gaols along English lines – one for Sydney and the other for Parramatta. [1] They were not built to house transported convicts. Rather, they were intended for domestic criminals, those committing offences within the colony and particularly in the cultural underbelly of Sydney.

In moral panic against the rise of a criminal class among currency lads and lasses, Hunter claimed that robberies were a daily occurrence. Thus prisons were needed in the main settlements. They were originally erected from material supplied by free landholders. Each settler was required to provide ten logs. Settlers on bigger properties, who employed more than 20 convicts, were expected to produce 20 logs. A communal effort to put in place an early prison system was created. Such was the enthusiasm that logs were brought at a much faster rate than carpenters could put them together. Thatching was also supplied by free settlers. [2]

The George Street Sydney and Parramatta gaols were completed in June 1797. Each was fitted with 22 cells, but both were burnt down in the same year by unknown arsonists, and then replaced by the more substantial sandstone dormitory buildings.

The decline of the George Street Gaol

Henry Kable, First Fleeter convicted of burglary in Norfolk, England, was placed in charge of the Sydney Gaol as Chief Constable in 1797, after first becoming a trusted overseer of convicts and then a constable and nightwatchman. He was dismissed as the gaoler in 1802 for illegally buying and importing pigs from a visiting ship in the port. [3]

The George Street gaol was enthusiastically described in 1800 as handsome and commodious with two undivided dormitories, one for men and one for women, separate apartments for debtors and six secure cells for the condemned. [4] It was army barracks in style with an enclosed parade ground. The cost of its operation, under the new governor Philip Gidley King, was met by import duties on spirits, wine and beer. [5]

Between the 1800s and the 1830s, public executions took place as the ultimate punishment for the same range of crimes as in England. At the same time, executions for prisoners incarcerated in Parramatta Gaol were conducted at Castle Hill. Last minute reprieves occurred, but there were also gruesome spectacles to please the Sydney and Castle Hill crowds.

By 1835, the Sydney Gaol was in an insecure and ruinous state and considered an eyesore with its timber gallows towering over its stone walls. George Street by this time was more respectable, with shops, commercial businesses and residences.

Thomas Macquoid, the High Sheriff, condemned the existing buildings, arguing that human conditions there were extremely shocking. He reported that 110 male prisoners shared a dormitory 32 by 22 feet (9.75 by 6.7 metres) while 40 women with 10 children were enclosed in the other, 27 by 22 feet (8.2 by 6.7 metres).

The outcome was that a Select Committee was appointed to examine the plans and estimates for the erection of a large metropolitan gaol at Darlinghurst to replace the George Street eyesore, a project that had stop-started from the early 1820s. The Select Committee presented its findings on 26 August 1836 to Governor Sir Richard Bourke.

Construction was soon recommenced. The foundations and part of the walls and gatehouse had been erected during Governor Brisbane's term between 1822 and 1824, but then deferred because of financial difficulties. [6] In 1826 overcrowding at George Street led Governor Darling to the temporary expedient of providing the hulk Phoenix to take the overflow, with the effect of delaying the construction of the new gaol. However, £10,000 was voted in 1835 by the Legislative Council to aid its completion.

Constructing Darlinghurst Gaol

The site chosen was the Woolloomooloo Stockade, an elevated area of windswept bush and sand dune, a kind of no-man's-land which had become a detention camp for those who could not be crammed into either the George Street Gaol or the Phoenix. The stone for the prison was quarried in nearby Barcom Glen – later the corner of Forbes and William Streets. Every block cut was marked with the convict's number or symbols called 'dargs' [7] 'Dargs' still can be seen on the outside walls.

[media]The construction at Darlinghurst was a massive public works project. Thirty thousand tons of sandstone were quarried for the walls alone. There were approximately 80 recurring 'dargs' on these walls that indicate the number of convicts cutting the stone. When a convict had cut his quota, he was then allowed to be assigned to a settler as a ticket-of-leave man.

In 1836, a chain-gang of 80 convicts had been stationed within the walls to construct the sandstone buildings, starting with A Wing, D Wing and the Governor's quarters, which they completed ready for occupation in 1841. At night, these convicts were housed in portable wooden boxes.

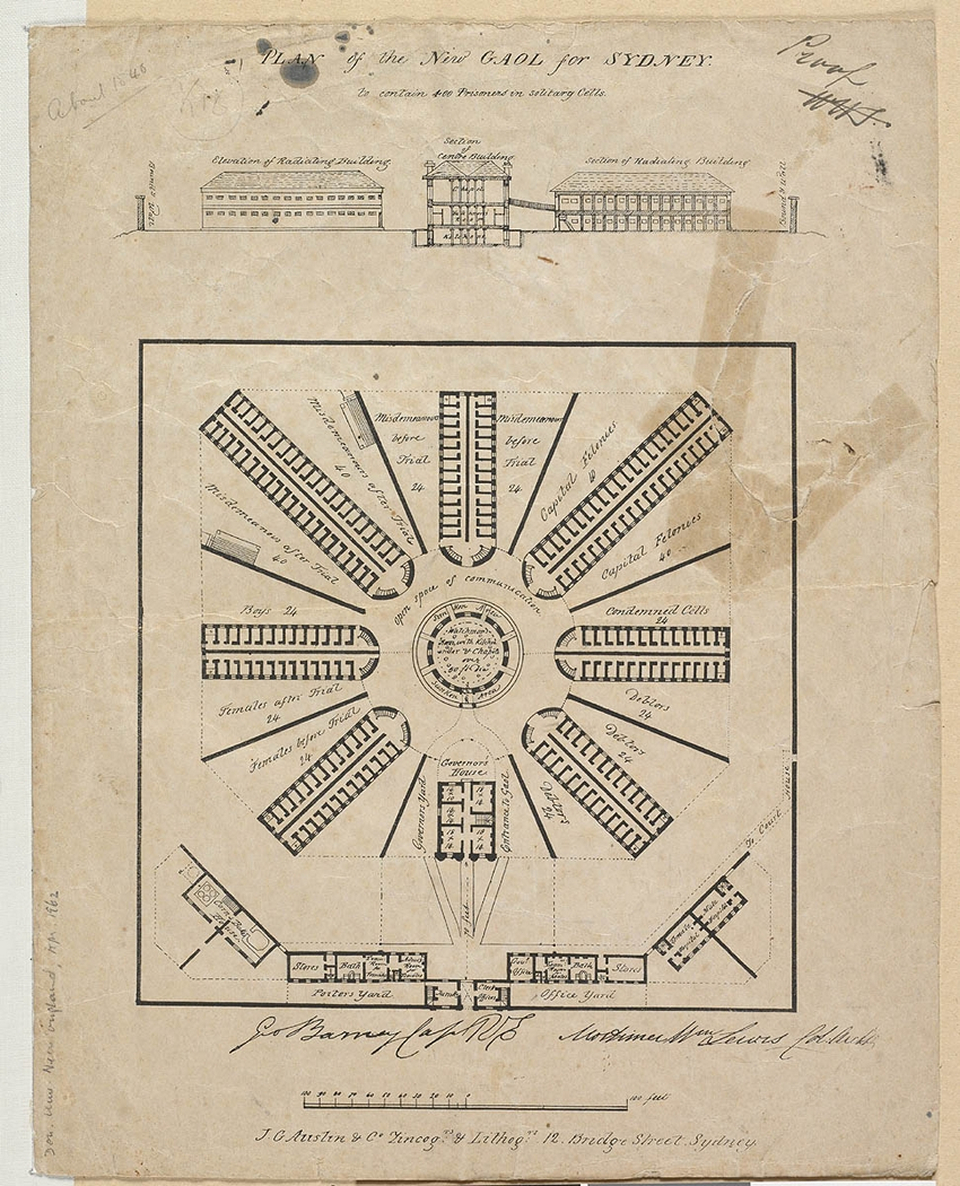

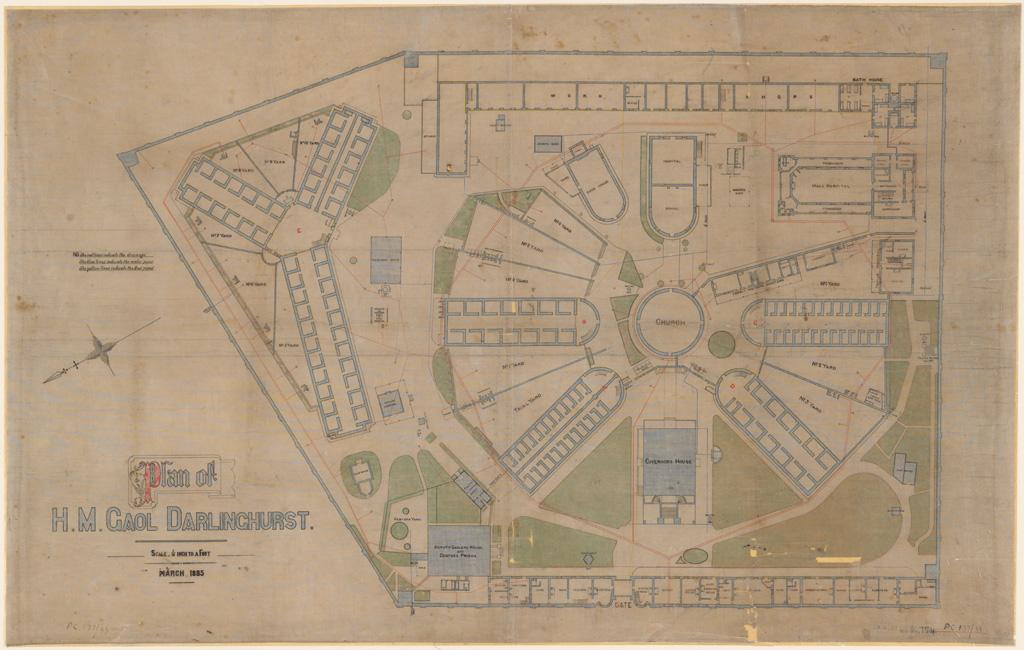

W Mortimer Lewis, the colonial architect, and Captain George Barney of the New South Wales Royal Engineers, designed Darlinghurst using the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia as a model. A radial design in the form of Jeremy Bentham's idea of the panopticon was used, with a central observational rotunda and seven separate two-storey cell blocks radiating from it. It was to be a system of solitary confinement for prisoners who were to be under constant observation.

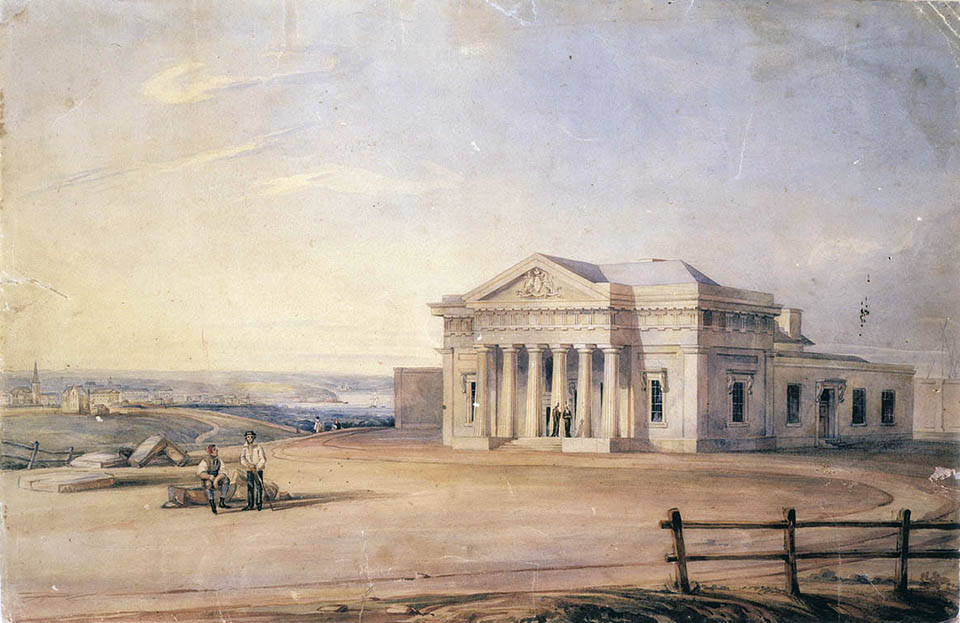

[media]The site is bounded by Darlinghurst Road, Burton Street and Forbes Street and by the Darlinghurst Courthouse on the Taylor Square side; this was also designed by Mortimer Lewis and completed in 1844. An underground tunnel was built from the gaol leading to the main courthouse, through which prisoners on trial were escorted to and from the court room. [8]

The march to Darlinghurst

On the morning of 7 June 1841, an unusual procession left the old George Street gaol and headed up towards Woolloomooloo Hill. At the procession's head was the wild-eyed Patrick 'Paddy' Curran, a notorious bushranger who was heavily ironed and on remand to face trial. Curran did his criminal apprenticeship under the bushranger known as 'Jackey Jackey' – William John Westward – who was executed on Norfolk Island after playing a leading part in an uprising. On 9 September 1841, Curran faced Berrima Court on separate accounts of murder and rape. Thus he was soon removed from his new quarters at Darlinghurst Gaol and hanged in public at the newly established Berrima Gaol, close to the scene of his crimes.

Behind the procession of male prisoners was a draft of 50 veiled female prisoners dressed in black and following the same route through the city. Hanging their heads, they received the same jeers and cheers from the mob. Their drab garb remained in use until 1909. [9]

'The ultimate home of the mug'

The first assembly at the new Darlinghurst Gaol was complete and inmates were assigned to their cells in their designated cell block. They were to be joined by others sent there by the newly built Darlinghurst law courts via the tunnel connecting the two institutions.

In 1849, B Wing was competed, providing more accommodation. In 1852, the last public hanging outside the gates took place, although executions continued inside the gaol into the first decade of the twentieth century. In 1861, C Wing was completed and the Y-shaped separate E Wing was built between 1864 and 1866. A modern gallows was built in the E Wing in 1869.

When Darlinghurst Gaol was opened, it stood alone on Woolloomooloo Hill, visible from Sydney Town as a warning against a life of crime. When public executions were conducted outside, the gruesome proceedings could be seen from afar. [10] Nevertheless, Darlinghurst was a great leap forward from the earlier gaols.

From 1867, prisoners were classified under the British Crofton system according to the legal character of the offences and the length of the sentences they had been given. The Philadelphia system in the United States and the Pentonville Model system in England were also influential. There were three distinct divisions of Darlinghurst inmates – A, B and C. The A classification was for serious crimes and dangerous, intractable prisoners, while the C classification indicated who had committed minor crimes or misdemeanours, such as inebriates, non-violent lunatics, debtors and others considered easy to control. The B classification fitted in between these two classifications. [11]

[media]In New South Wales, a solitary confinement regime for prisoners was organised from the Philadelphia system, for up to nine months depending on the length of the sentence. The prisoner worked, ate and slept in his cell and took exercise by himself. The emphasis was on solitary and sorrowful repentance. The subduing state of solitude would lead, it was believed, to the maintenance of perfect order in the prison. [12] Drawing from the convict era, colonial administrators chose to use physical punishment, by flogging, leg irons, solitary confinement and the gallows, believing it to have a punitive effect. Such punishments were gradually watered down. Woven into it all was the high Victorian notion of the possibilities of moral, social and spiritual reform of prisoners.

By the 1870s, Darlinghurst was well established as a 'labour gaol' – a gaol that had workshop facilities for employing prisoners. Parramatta was another labour gaol, and there were gaols at Berrima, Maitland, Goulburn and Bathurst, all 'hives of labour' based on the Darlinghurst model. By the end of 1877, Darlinghurst had 596 inmates, of whom 453 were men and 143 were women. During that year, there was a large turnover – 8,016 entries and 7,966 discharges. And by this time it was overcrowded, as there was separate cell accommodation for only 348 prisoners. [13] Most of the solitary accommodation had to be abandoned.

Replacing Darlinghurst

In the 1900s when Henry Lawson was making frequent short-term visits to its cells as a vagrant or inebriate, Darlinghurst was considered an obsolete institution, unfit for the modern era of penology. Municipal authorities called it a 'social blot' in what was by then a heavily populated and prominent residential area. Owners of surrounding properties were agitating for its removal. [14] It was seen as an obstacle in the path of city improvement. As a result, by 1909 Darlinghurst was already two-thirds unoccupied and its closure as a major prison was imminent, with Parramatta, Bathurst and Goulburn gaols all being expanded to help empty it out.

To replace Darlinghurst, a state penitentiary complex was erected in south-eastern Sydney in the sandy dunes of Long Bay and adjacent Little Bay. The new penitentiary was opened in stages. The State Reformatory for Women at the Little Bay end of the vast site was first proclaimed on 25 August 1909. All the Darlinghurst Gaol women were transferred there, together with those in Biloela (on Cockatoo Island) and Bathurst. Thus the incarceration of women became centralised. Women who were removed from small country gaols were those who had committed serious offenses. The new Female Reformatory had room for 300 prisoners. This was viewed as adequate, as fewer women than men were committed from the law courts.

On 1 June 1914, the Long Bay State Penitentiary was proclaimed and 32 prisoners were sent there to prepare it for general occupation. Forty-two days later, all prisoners had been removed from Darlinghurst to the coastal penitentiary complex with all the necessary stores, furniture and equipment. Detention at Long Bay was considered infinitely superior: the new cells were healthier and better situated and the labour occupation on a much larger site could be more varied. [15]

Darlinghurst, for the majority of its existence, had been the principal manufacturing gaol in the New South Wales system of prisons, and had had inmates comprising all classes of criminals. It had also been the largest prison. The buildings remain as an outstanding colonial landmark in a pleasant position with what used to be a fine prospect over the surrounding cityscape before modern high-rise occurred. Passersby can still see the massive walls and sandstone buildings inside built to last forever, now housing the National Art School and a technical college.

Parramatta Gaol

The history of Parramatta Gaol parallels Darlinghurst, except that it escaped permanent closure even though there were temporary closures in the 1920s and again in the1980s. The 1835 Report condemned the old Parramatta Gaol as containing overcrowded dormitory apartments in imminent danger of falling down. One was for chain gangs, one for debtors, one for women and one for male prisoners committed for trial. Finally, a decision was made to erect a new gaol near Hunter Creek on the northern outskirts of the town on block 76, which was three and a half acres (1.4 hectares). Tenders were called for in September 1835, and by early 1836 the foundations had been laid. The building was designed by W Mortimer Lewis with similarities to the plans for Darlinghurst.

In November 1841, the building of the new gaol was so far advanced that it had been roofed and at least half was ready for occupation. The criminals were moved from the gaol at Alfred Square, Church Street, Parramatta on 15 January 1842. This event was neck-and-neck with the occupation of Darlinghurst. The two events were connected by an official policy of expansion.

The square surrounding the wall of Parramatta Gaol had been completed in 1837. The new prison contained five cell blocks, a central chapel and attached warder quarters. When the new gaol was occupied, the old one was demolished. By 1846, the male inmates were engaged in breaking blue metal for road works. The doctrine of useful hard labour was thus applied.

Over the decade, new buildings continued to be erected and were not completed until 1854. Mortimer Lewis's plan had been modified, especially in respect to the central block. The wings became three storeys rather than two. The three wings that had been built were numbered from the south 1, 2 and 3. A gate-lodge consisting of upper and lower rooms on each side of the entrance was also designed by Lewis.

With the closure of smaller gaols at Windsor, Campbelltown and Liverpool, there was a ready influx of prisoners to Parramatta. Number 3 wing was used for women until female prisoners were removed to Darlinghurst in 1863. Parramatta's central block was used for offices and gaolers' quarters, and the rear upper room served a dual purpose as chapel and schoolroom for the elementary education of illiterate inmates. Two hospitals, one for males and the other for females, were built at Parramatta as in Darlinghurst. In 1859, the Parramatta site was expanded by enclosing a portion of land on the town side.

By the 1890s, Parramatta Gaol was providing industrial training. They had a large, well-equipped blacksmith's shop and other workshops. It had become a 'hive of industry'. Thus they went beyond punishment and restrictive confinement to the notion of reform by useful work. But by the 1880s, prison accommodation was not keeping pace with population growth. [16]

Shaftesbury Girls' Reformatory

New ideas about dealing with young female prisoners were also implemented. The New South Wales Department of Prisons took over from a voluntary organisation, the Shaftesbury Girls' Reformatory at Vaucluse on the Old South Head Road. It had started with four girls in 1878. By the end of 1880, the number had risen to 17 under-16-year-olds who were sentenced for criminal offences. The Shaftesbury Reformatory was modelled on the cottage plan to house the relatively small number who had moved from the Biloela Reformatory when it was closed down in 1878. The building was designed around an enclosed courtyard used for the girls' private recreation. To create further privacy, the building had few external windows.

The purpose of Shaftesbury, under the control of Harold Maclean, Comptroller General of Prisons, was that the girls were to be taught 'habits of cleanliness, industry and diligence' so that 'moral and pious conduct' could be developed. The girls were to be treated with kindness combined with strict discipline – at least in theory. Time each day was set aside to teach domestic skills and household management. An elementary school operated each morning until 12 pm and from 2 to 4 pm in the afternoon. Domestic training and work were fitted in around these times. The girls were kept busy.

Some inmates found themselves incarcerated at an older age in the Women's Reformatory at Long Bay. [17]

The Women's Reformatory, Long Bay

'They have sold their bodies and would sell their souls for drink to drown

Memories of wrong that haunted them – haunt the women of the town'. [18]

When Dulcie Deamer, journalist and colourful avant-garde Queen of Bohemia, visited the Women's Reformatory to do a story for a magazine in 1925, she had to stoop to pass through the high security metal postern door at the gates. She found the Reformatory, like the adjacent Long Bay Penitentiary, was close to the rugged coastline in the east, Botany Bay to the south, and to the west the vast flat countryside of the Cumberland Plain. The Women's Reformatory she gazed upon consisted of a central glassed circular Benthamite conservatory, set in a spacious quadrangle around which four large halls radiated as diverging wings, each containing 72 individual cells for women. There were two large ventilated workshops for needlework and allied domestic skills, and a special lock hospital with a visiting surgeon for those placed there under the 1908 Prisoners' Detention Act which required a complete cure from venereal disease before release into the cell block. There was a large kitchen with modern appliances, a supply of steam for heating baths and washing water in the laundry. A tramway line ran within the grounds from the outside. The prison tram conveyed women to and from the Darlinghurst Courts some miles away.

When Deamer visited, a chapel existed for spiritual comfort. At the main entrance were found a complex of bath and reception rooms to receive inmates, to check them for infectious diseases, to wash them and supply them with clean pastel-coloured prison outfits (in contrast to the old black drab uniforms of previous years) before they were passed on to the halls and their cell. They were placed under a strict classification system.

Each woman occupied a single cell and was supplied with uplifting literature and an electric light to read by until 'lights out'. Deamer described all this with some irony:

Wide paved spaces and beyond the range of bars dividing up the exercise yards that are big open-air cages. Great heavens! It is reminiscent of a zoo! But these hefty, capable, pleasant-faced women in crisp, blue print dresses? They are the wardresses. They give the hospital touch to the picture...the matron takes charge of us. Here is a woman in a thousand, a 'tower of strength', if ever there was one. Her grey eyes briefly examine us, and one is moved to think, instantly of Napoleon's generals...She is in white, like a nursing sister and again the atmosphere of a hospital overrides the first ludicrous impression of a zoo. [19]

It was a far cry from Darlinghurst's damp dark cells and inmates in hideous black dresses and veils – a place rooted in a pessimistic Victorian view of the possibilities of reform of degraded or fallen women.

Nevertheless, regulations framed control of every aspect of behaviour in the shiny new reformatory. The women were assigned three tasks – needlework, laundry work and sweeping. Early each morning, the routine of marching in silence in a circle had been replaced by a new system of vigorous physical drill and exercise, based on the Swedish method, followed by a cold shower bath. Erect deportment was encouraged. An incentive system for the women moved them from one grade to the other after entry, with an expanding scale of small rewards. Each inmate had the opportunity through good conduct to reach the Special Class where privileges were extended to playing a game of chess, draughts, dominoes, and so on. It was a model establishment that provided individual counselling from the Ladies' Committee of the Prisoners' Aid Society.

The charges that saw the inmates committed ranged from indecent language to soliciting in the street, keeping a disorderly house, drunkenness, assault, stealing and vagrancy. A few had committed murder. Many who found their way there had had a long sad experience of institutionalisation, some from early childhood. Deamer cited the case of Fanny K, who had done no regular honest work for a long while. She had received 14 charges of stealing, four for vagrancy and two for being drunk and using bad language. She had been brought up in the Parramatta Female Orphan School and on her liberation had embarked on a life of petty crime. She had lived rough in the alleyways. After completing her sentence at Long Bay, she desired to enter the Newington Asylum to spend the rest of her days there.

After her visit, Deamer reached a devastating conclusion:

So the Reformatory, with all its efficiency and beautiful machinery of hygiene and humane discipline, was much sadder than any hospital, for a hospital is a place of great hope. Here there is no need to grave 'Hope Abandon' above the entrance. For the majority of those entering here there had never really been any hope to lay aside. [20]

Emu Plains Prison Farm

Ideas about 'Afforestation' and Agricultural Training Camps were part of the modernisation of the system immediately before and after World War I. Agricultural and horticultural training had been in full swing in the principal gaols for some years, but faced the major restrictions of prison walls.

The first Afforestation Camp for low security prisoners was opened at Tuncurry in October 1913; others were progressively established in the countryside. The Sydney facility was founded soon after Tuncurry at quasi-rural Emu Plains on 107 acres (43 hectares) near Penrith. Situated on the banks of the Nepean River 35 miles (56 kilometres) from the city's centre and about a mile (1.6 kilometres) from Emu Plains railway station, Emu Plains Prison Farm became a place of detention in December 1914. The purpose was to supply vegetables and other produce to government institutions in Sydney, including its prisons. Ten wooden huts in the place of cells were first constructed in the workshops of Goulburn Gaol and transported to the site. The first batch of prisoners arrived there on 12 April 1915. At first, the Department of Prisons was responsible for the supply and control of prison labour and the Department of Agriculture was responsible for the system of cultivation. Because of interdepartmental rivalry, this dual system lasted only about a year; then the Department of Agriculture took over the entire running of the prison farm. The prisoners were released under license to the Department of Agriculture and the farm was disestablished as a prison and became the Emu Plains Irrigation Farm. The Department of Agriculture appointed its own supervisor. This system worked better for a while – until the farm was placed back under the Department of Prisons in November of the same year.

Prisoners sent to Emu Plains Prison Farm were first offenders below the age of 25. The whole idea, apart from vocational training, was to protect first offenders from the corrupting influence of older, more hardened criminals in the main city prisons.

Many of the first intake at Emu Plains farm were transferred from Goulburn Gaol and some from the main city prisons. The results in the first decades were good, the numbers of re-offenders small.

Eventually, 42 healthy and comfortable huts were established. The operation developed into a systematic training in general farming. Prisoners with good behaviour records were selected for posting to the farm. Consideration was given to recreation with the provision of the usual outdoor sports as well as farm work.

The farm was profitable. There were rich fields of vegetables – rhubarb, asparagus, carrots, parsnips, cabbages, tomatoes and potatoes – as well as pigs, poultry and a dairy farm. The wooden huts were arranged around a quadrangle with a drill square as part of it. Drill was a daily activity. The young offenders ate alone in their huts at a small table under which was a food-safe made by kerosene tins and wire gauze that held extra food brought in by relatives, usually on Sundays, the main visiting day. There were no walls or high barbed-wire fences enclosing the institution, but warders were on guard duty. An honour or parole system was enforced. Attempted escapes were uncommon. [21]

Conclusion

Penal practice was an eclectic mix of overseas models, moving from the brutal English county lock-up to elaborate machine-like buildings such as Darlinghurst and Parramatta where prisoners were placed in separate cells – solitary confinement – under Benthamite observation based on the Panopticon principle and ritual. As one Bulletin writer observed in 1882

Upon the tower reclines as usual the watchful warder. He is holding across his knees – force of habit in consequence of so frequently nursing a baby – his regulation rifle, upon the barrel of which, and upon his martial 'bagginet' the sun gleams pleasantly. [22]

The prominent early Comptroller-General of Prisons Harold Maclean created the gaol as a 'hive of industry', of industrial training, elementary education and restricted association. His successor Frederick Neitenstein, who guided the system into the first years of the twentieth century, added to it by using Alexander Maconochie's far earlier penal reform on Norfolk Island – a system of incentives through marks, enabling the well-behaved prisoner to move from one grade to the other, with an expanding range of privileges and small freedoms available. It was a matter of climbing the incentive ladder to release and freedom.

A lasting reform by Neitenstein was the setting up of modern techniques of identifying criminals through the systematic Galton-Henry method of fingerprinting, which was added to photography, established in the 1870s, and written description of prisoners as practiced at Darlinghurst and Parramatta.

References

Deborah Beck, Hope in Hell: A History of Darlinghurst Gaol and the National Art School, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2005

Clive Faro, Street Seen: a History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 2000

James Semple Kerr, Design for Convicts, National Trust of Australia (NSW) and Australian Society of Historical Archaeology, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1984

James Semple Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, SH Erwin Gallery & the Australian Bicentennial Authority, Melbourne, 1988

John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996

John Ramsland, Most Healthily Situated? Maitland Gaol 1844–1998, Verand Press, Sydney, 2001

John Ramsland, 'Dulcie Deamer and the Women's Reformatory, Long Bay', Journal of interdisciplinary gender studies, vol 1, no1, 1995, pp 33–40

'History of NSW Corrections', Corrective Services NSW website, http://www.correctiveservices.nsw.gov.au/about-us/history-of-nsw-corrections, viewed 6 April 2011

Notes

[1] Charles H Bertie, The Story of Old George Street: A Chapter in Old Sydney, Tyrells, Sydney, 1920, p 13

[2] Governor John Hunter, Government and General Order, 26 September 1796, Historical Records of Australia, vol 1, p699 and 19 May 1797,3, pp 139, 209

[3] DR Hainsworth, 'Kable, Henry (1763–1846)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1978, pp 31–2

[4] Hunter to Under-Secretary King, 25 September 1800, Historical Records of Australia, vol 4, p 153

[5] Governor King to Commissioner Palmer, 27 June 1801, Historical Records of Australia, vol 4, p 418

[6] Charles H Bertie, Old Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1911, p 22; also HC Brewster and V Luther, King's Cross Calling, HC Brewster, Sydney, 1945, pp 67–70

[7] HC Brewster and V Luther, King's Cross Calling, HC Brewster, Sydney, 1945, p 70; Freda MacDonnell, Before King's Cross, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1967, p 93

[8] James Semple Kerr, Design for Convicts, National Trust of Australia (NSW) and the Australian Society for Historical Archaeology, Sydney, 1984, p20; pp 97–100; Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon, (Annotated Chart), London, 1791

[9] No 54, by 'Old Chum', 18 October 1908 Newspaper cuttings, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, Q991/N

[10] Deborah Beck, Hope in Hell: A History of Darlinghurst Gaol and the National Art School, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2005, pp ii–iii, 1–9

[11] John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996, pp 34–8

[12] Michael Ignatieff, A Just Measure of Pain: The Penitentiary in the Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850, Peregrine, Ringwood, 1978, pp 194–5

[13] John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996, p 44

[14] John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996, pp 81–5

[15] 'Long Bay Penitentiary: Founded on Good Lines – Equal to the Best', New South Wales Police News, vol 12, no 8, 1932, p 5; 'In a Penitentiary Garden Relieved of Iron Bars', New South Wales Police News, 7 November 1921, p 28; 'State Penitentiary: A Suitable Building', New South Wales Police News, 7 November 1921, p 9

[16] John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996, pp 87–91

[17] Copies of letters sent to Department of Justice and other Public Officers, 30 November 1880 to 27 April 1882, vol 4/6483, State Records NSW; John Ramsland, Children of the Backlanes, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986, pp 204–5

[18] Henry Lawson, 'The Women of the Town'

[19] John Ramsland, 'Dulcie Deamer and the Women's Reformatory, Long Bay', Journal of interdisciplinary gender studies, vol 1, no1, 1995, pp 33–40

[20] John Ramsland, 'Dulcie Deamer and the Women's Reformatory, Long Bay', Journal of interdisciplinary gender studies, vol 1, no1, 1995, pp 33–40

[21] Reports of the Comptroller-General of Prisons 1916, 1917, Govt Printer; 'The Prison Camps of New South Wales', undated typescript ms, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library; John Ramsland, With Just But Relentless Discipline: A Social History of Corrective Services in New South Wales, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1996, pp 209–21

[22] 'In the Jug', Bulletin, 25 March 1882

.