The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Painting Old Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Urban life, art and the roots of heritage conservation in Sydney

The Rocks was always Sydney's 'old place', even when it was new. Convicts arriving on ships were delighted to see such a familiar urban landscape. The houses scattered on the rugged slopes looked much like the simple vernacular cottages of England and Ireland. Their blunt shapes, cropped eaves and knobbly stone walls became strikingly different to the modern styles of the city as it expanded over the decades. [1]

With its population of working people, sailors, the Irish and Chinese, the Rocks in the nineteenth century was a magnet for ministers, philanthropists and slum clearance advocates. All came to wander the streets, peer into windows and over back fences and even invite themselves into homes. All assumed they saw a people living in the darkness of filth and immorality; all of them felt the tantalising shadow of the dark convict past. [2]

Like other large cities at the end of the nineteenth century, Sydney faced serious urban problems such as poor sanitation, overcrowded and substandard housing and epidemic diseases which killed thousands, particularly in poor and working class areas. The Rocks and Millers Point were often regarded as the sites with the densest concentration of urban ills – they were stamped with the stigma of physical as well as moral disease. Yet from the 1850s, the streets, lanes and drainage were slowly improved and sewerage was gradually extended to serve almost every home. Gas was connected in the 1860s and 1870s and from 1886 a clean, safe and reliable water supply from the Upper Nepean Scheme was available. Residents' lives improved immensely as a result of these measures. Infant mortality statistics for inner-city neighbourhoods like the Rocks and Millers Point fell considerably from 1880 on, while they rose in the so-called 'healthy' suburbs. [3]

Yet when bubonic plague broke out in Sydney in 1900, all eyes turned accusingly to the Rocks and Millers Point, and long-held fears about the area appeared to be confirmed. The disease was brought ashore by fleas on rats from visiting ships, so those who worked on or near the waterfront areas, like Millers Point, were most vulnerable. Only five people in the Rocks contracted the disease. Nevertheless, the city improvers promoted plans to resume, demolish and rebuild extensive tracts in the area in the name of public health and sanitation. Photographs taken by John Degotardi and more especially George McCredie provided classic 'slum' images of decrepit and chaotic housing and poorly clad 'street' children. In retrospect this can be seen as part of much larger global patterns, as working class people and their housing were shifted out of city centres worldwide to make way for business and industry, so creating 'modern' cities. [4]

In 1901, when these old Sydney neighbourhoods were apparently doomed to extinction through demolition and redevelopment, there was a curious reversal in sentiment. As the seemingly inevitable destruction drew closer, the blighted neighbourhood became a site of affection and romance. What had been appalling was now appealing. Notable artist Julian Ashton persuaded the then Minister for Works, EW O'Sullivan, to provide funds for purchasing artworks depicting 'Old Sydney'.

An exhibition of pictures of Old Sydney

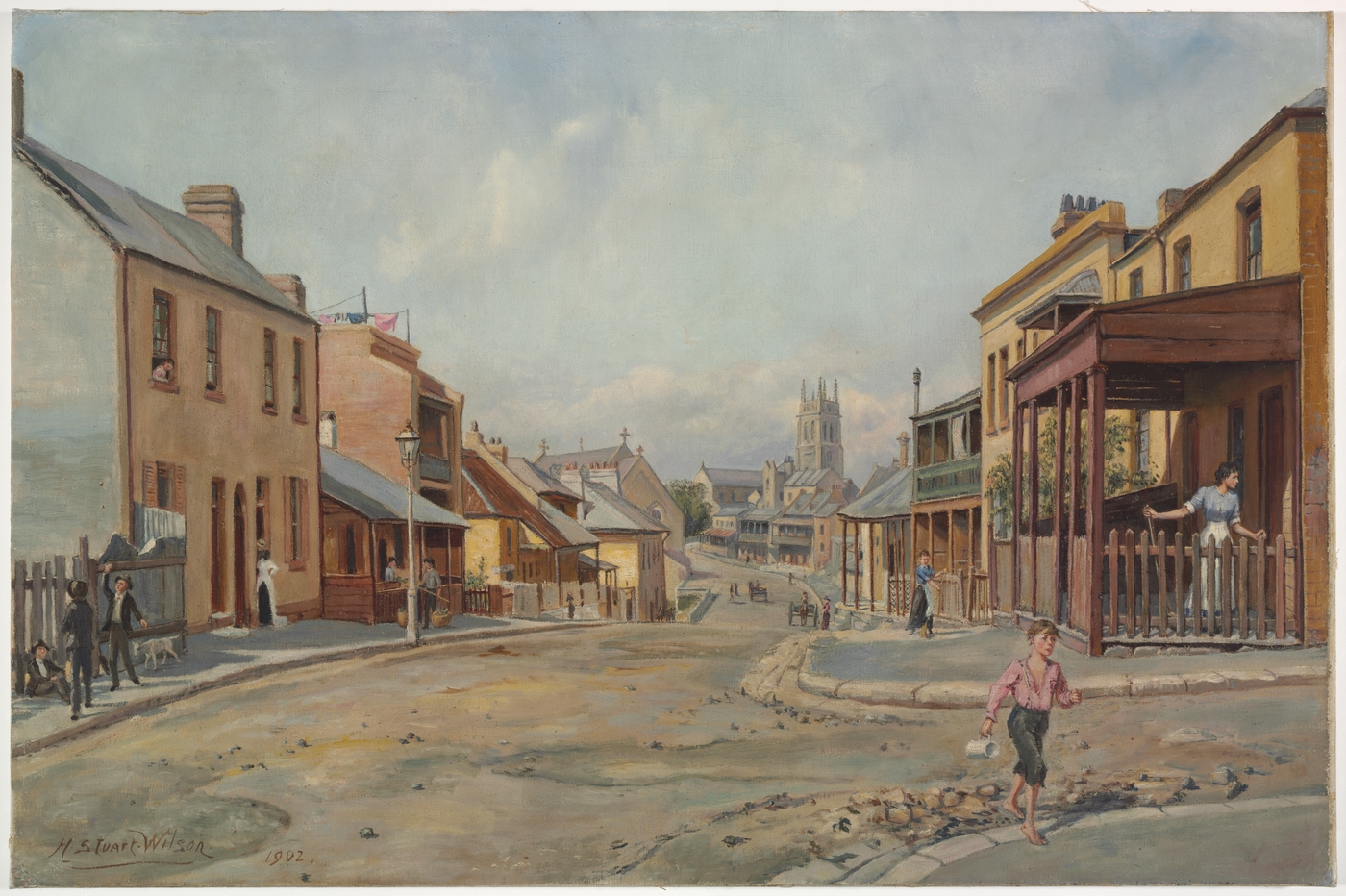

The exhibition that brought these paintings together was An Exhibition of Pictures of Old Sydney at the Society of Artists' Rooms on Pitt Street in March 1902. Artists were invited to paint 'old' Sydney at risk of demolition. One hundred and forty-five works were submitted for the exhibition, primarily depictions of The Rocks and Millers Point. Charged with the 'difficult task of choosing works illustrating in a typical way the fast disappearing remnants of old Sydney quite as much as the purchase of works artistically good' [5], the selection committee chose 15 works for government purchase, including paintings by the well-known artists Julian Ashton, Sydney Long, Walter Spong, Fred Leist, Clarence Backhouse, Alice Muskett, Howard Ashton and H Stuart Wilson.

The Old Sydney paintings depicted the world as it once was – a world without machines, factories or clocks. They show small, intimate places shaped by hand, houses, pubs and shops, children playing in the street, makeshift clothes lines, cottages with wide eaves and plastered brick, horse-drawn carts, gas lamps, sailors, street hawkers, goats and chickens.

[media]It was, of course, a partly contrived vision. John Degotardi's 1901 photographs of the same streets and vistas reveal that, while artists depicted the built environment in an astonishingly realistic way, details like goats and chickens wandering the streets were mostly fantasy. Roads were made to look more uneven that they were, roofs were shown patched when they were not. Most striking of all, the painters deliberately erased the unmistakable signs of modernity. Busy shops, men hurrying off to work, large advertisements on hoardings and the sides of buildings, telegraph poles and wires – all were banished from these visions of Old Sydney. [media]The artists created myths quite at odds with the real, busy, lived Rocks – they placed working class and poor people, especially women, outside the realm of modernity. They belonged to a sleepy, slow, old-fashioned past, an age which was fast slipping away.

At the same time, the paintings of The Rocks and Millers Point stood in direct opposition to the received and contemporary view of the area and its inhabitants. By rendering Sydney's most notorious slum district in picturesque and sentimental terms, with local residents at the heart of the pictures, the artists proposed an alternative set of urban, social and aesthetic values. At a time of destruction and change, these paintings gave form and narrative shape to feelings of affection, concern and loss. They were instrumental in fostering the earliest appreciation of Sydney's old buildings and the early townscape. This sensibility became a constant stream, growing in strength and conviction over the twentieth century. Eventually it turned the tide against the idea that the destruction of heritage is the necessary price of modernity.

The Old Sydney exhibition was the first documentary material that shows an interest in Australia's urban past. It was the birth of action aimed at securing Sydney's past in the face of the speed of modernization. It also created an informal network of artists, architects and historians who, during the first years of the twentieth century, produced words and pictures inspired by colonial architecture and motivated by protecting this historical essence from the modernisation of Sydney.

The Old Sydney network

The Old Sydney network was by no means politically or socially homogeneous. Julian Ashton, Albert Henry Fullwood and George Collingridge had experience and appreciation of urban subjects. Ashton, who claimed to have painted Australia's first plein air painting, was a leading champion of the immediacy and accuracy of art created directly from the subject. His art school was a focal point for the most prominent Sydney artists.

In contrast, Lionel Lindsay, one of Australia's leading printmakers and opponents of the modern movement, did not participate in the Old Sydney exhibition. Lindsay described modernism as 'loaded up with leprosy of the ages. It is offensive to the eyes' – a conservatism shared by many of the Old Sydney group. [6] Nevertheless Lindsay made a career of Old Sydney, producing hundreds of charming and intimate views of the streets, locales and buildings about to be demolished to make way for the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the 1920s and 1930s.

Sydney Long exhibited several paintings in the Old Sydney exhibition of 1902 that displayed a consciously realist technique and subject matter at odds with his usual marriage of European mythology and Australian landscape. Sydney Ure Smith, the city's leading proponent and populariser of modern design and consumer lifestyle, used his black and white illustrations and hand-coloured drawings of the built environment as propaganda for its preservation. Charles Bertie and Sydney Ure Smith's Old Sydney of 1911 is probably the best display of Ure Smith's draughtsmanship and 'his love of architecture as an evocative link with colonial Australia'. [7]

Although the Old Sydney campaign was expressed primarily in paintings, etchings and prose, photography also played a role. Photographers had depicted The Rocks and Millers Point for many years, not least in the McCredie collection of government photographs that helped bring about the 'slum clearance' of The Rocks. The Old Sydney movement's preference for art over photographic records was appropriate to its aim of historicising and romanticising the area.

The exception to this was Harold Cazneaux. Anxious to enhance the artistic credibility of photography, Cazneaux shared both the subjects favoured by his printmaking contemporaries and the desire to create carefully composed pictures – 'dense and often sombre tonal effects, and…carefully constructed to achieve the compositional coherence of a print or watercolour'. [8] Cazneaux's depictions of Rocks children, especially, are among the best-known statements of the Old Sydney school.

Urban development, urban preservation

Old Sydney can be read as the beginnings of urban preservationist activity through which artists and antiquarians sought to document and preserve colonial architecture in the face of a perceived homogenisation of the city. Sydney's unwavering love of development and change indicates that for many, little has changed in more than 100 years. Indeed, Frank Walker's 1908 call to arms could have been written today:

What are we doing at the present day in the way of the preservation of historic spots and landmarks in our city and country? This is a question which every year becomes more and more insistent. And it is an important one if we are to go down to posterity as a people who, mindful of generations yet unborn, seize the opportunity now, to keep the links of our historic chain intact. What says the callous individual, intent on more moneymaking and the aggregation of creature comforts? No time for sentiment? [9]

References

Paul Ashton, Caroline Butler-Bowden, Anna Cossu and Wayne Johnson (eds), Painting The Rocks: The Loss of Old Sydney, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2010; produced in association with an exhibition at the Museum of Sydney on the site of the first Government House, 7 August to 28 November 2010, a joint initiative of the Historic Houses Trust and Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

Notes

[1] Grace Karskens, The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1997

[2] Grace Karskens, 'Small Things, Big Pictures: New Perspectives from the Archaeology of Sydney's Rocks Neighbourhood', in Alan Mayne and Tim Murray (eds), The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, pp 69–85

[3] Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp: Sydney 1870–1890, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, pp 99–100; Grace Karskens, Inside the Rocks: The Archaeology of a Neighbourhood, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1999, pp 86-90

[4] Grace Karskens, Inside the Rocks: The Archaeology of a Neighbourhood, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1999, pp 191–4; Register of cases of Bubonic Plague, 1900–1908, series number 591, X647, State Records of New South Wales; Peter Curson and Kevin McCracken, Plague in Sydney: The Anatomy of an Epidemic, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, c 1987; Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point: The Urban Village, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 69–74; Alan Mayne, Representing the Slum: Popular Journalism in a Late Nineteenth Century City, Department of History, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 1990

[5] The Art Gallery of New South Wales acquired these works. Five are still held by the gallery; the others were transferred to the Mitchell Library in 1920. Other paintings from the exhibition are held by the National Library of Australia or are in private hands. In particular, the extraordinary private collection of Fred and Elinor Wrobel houses a number of paintings from this exhibition

[6] Melbourne Herald, 14 October 1927

[7] Nancy DH Underhill, Making Australian Art 1916–49: Sydney Ure Smith, Patron and Publisher, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1991, p 31

[8] Joanna Mendelssohn, The Life and Work of Sydney Long, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, 1976, p 31

[9] Frank Walker, 'The Historic Landmarks of Sydney: Their Need of Preservation,' Art and Architecture, May–June 1907, p 88

.