The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Old Toongabbie and Toongabbie

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Old Toongabbie and Toongabbie

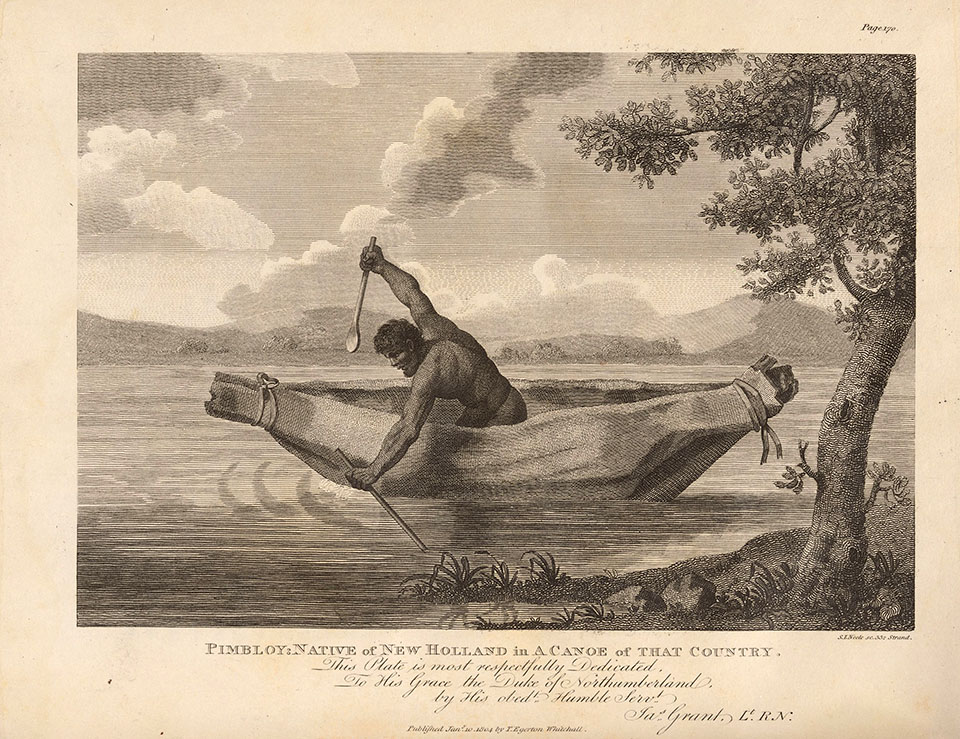

The Indigenous people who inhabited the Parramatta River and its headwaters found this part of the country highly suitable as a place to live, with its ample fresh water, prolific plant and animal life and temperate climate. A number of clans or families known generally as the Darug gradually settled along the river. At the head of the river were the Burramattagal (or Barramattagal) of Parramatta, while to their west and north lived the Bidjigal, another Darug group: the Bidjigal were known in both the Castle Hill and Botany areas. Pemulwuy,[media] the guerrilla leader who features in the early history of the district, was of this clan. Another known identity of the Bidjigal was Pemulwuy's son Tedbury.

They lived on a diversity of plant and animal life from the streams and the bushland. Fresh water streams yielded mullet, crayfish, shellfish and turtles. Male food-gathering activities ranged from trapping and hunting native animals to collecting bull ants and their eggs and larvae of the longicorn beetle (the witchetty grub). All were prized and sought in the never-ending daily quest for food. Animals such as lizards, snakes, birds, potoroos and wallabies were all hunted. Of these activities, possum hunting was probably the most fruitful, the method of capture being to smoke them out of their hollow tree haunts. [1]

Toongabbie Creek[media] was situated in an alluvial valley that ran eastwards from Prospect to the sea, dominated by stands of tall timber, together with gullies providing humid and fire-free conditions that developed closed canopies supporting patches of local rainforest or 'brush' in the rich soil. Patches still remain along the creek between Oakes Road and Briens Road. The turpentine ( Syncarpia glomulifera) and the coachwood or scented satinwood (Ceropetalum apetulum) were common, as were the lillypilly (Acmena smithii) and the water gum (Tristaniopsis laurina). [2]

The spread of settlement around Rose Hill

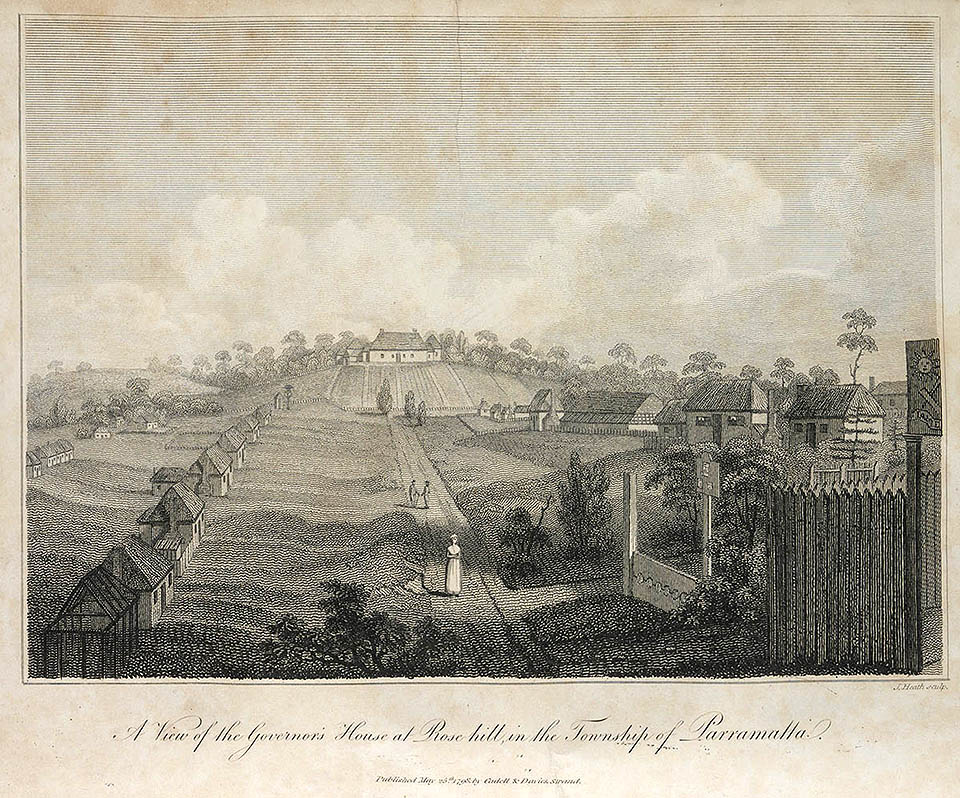

Governor Arthur Phillip established the government farm at Rose Hill in November 1788, to develop an agricultural community that would make the colony almost self-sufficient. The township at Rose Hill developed as an administrative and market centre, and settlement expanded around it. The river and creek lands to the west were fertile, only needing clearing. Phillip decided to expand the settlement to the north-west along the river valley after the Second Fleet arrived in June 1790.

The first expansion of the township of Rose Hill was a new 'public settlement' built about a mile and a half (2.4 kilometres) to the north, on the south side of the 'creek' in the corner of land formed by Toongabbie Creek and the head of the river. This site was initially referred to as 'the new grounds'. Collins first mentions it in August 1791 and mentioned that clearing would result in about 40 to 50 acres (16 to 20 hectares), allowing corn to be planted in season. The labour was directed by Thomas Daveney. Cultivated land was gradually extended to 134 acres (54 hectares), and 13 large tent huts were built there. Huts may be seen on the first plan drawn of the area. The site is occupied by today's Westmead Children's Hospital and remnants of the Psychiatric Centre Farm. [3]

Toongabbie – the second settlement

[media]It was only a matter of time before a 'second settlement', further up the main (Toongabbee) creek was planned by Phillip, who appointed Thomas Daveney to select, plan and superintend a more extensive farming area. A site was chosen about two miles (3.2 kilometres) further on and, until a township was laid out. In his dispatch of October 1792, Phillip outlined that

a new settlement [was] formed about three miles to the westward of Parramatta and to which I have given the name Toon-gab-be, a name by which the natives distinguish the spot.

Legend has it that this was the first colonial town to be given an Aboriginal name. Even admitting that names were given to places often before being officially committed to print, Parramatta was named by Phillip in June 1791 on the King's birthday and Toongabbe in July of that year. [4]

The site chosen for the settlement is shown on the plan, The Town of Toongabby, and was located on the banks of Toongabbee Creek between what is now Old Windsor and Oakes roads. [5] The superintendent, the military and the stores were located on the northern side of the creek. The town plan was laid out by Phillip (perhaps with the assistance of his Surveyor General, Augustus Alt) and shows the same studied simplicity as may be seen at Rose Hill. Although it lacked the boldness and 'picturesqueness' of the street plan of Parramatta, it was not merely another grid plan. [6]

[media]An early drawing, A western view of Toongabb e, depicts the buildings on the site. There appears to be 20 convict huts that agree with the layout of the 1792 plan, The Town of Toongabby. [7] The design of the huts appears to be similar to those built at Rose Hill but instead of 10, they were planned to hold 20 occupants. They were of wattle and daub construction with gabled roofs of thatch. There is no mention of brick kilns or brickmaking although each hut appears to be complete with a brick chimney.

The principal agricultural centre

By 1792, farming had ceased entirely at Sydney, and Toongabbie was becoming the principal farm, as Phillip had intended. Daveney was a hard taskmaster and drove his convicts relentlessly through his assistants, 'a set of merciless wretches' often chosen from the toughest and most brutal convicts. Newly arrived male convicts were sent direct to Toongabbie, even if ill and emaciated from their long voyage, those surviving one test often succumbing to the next. Those capable of handling a spade or hoe were set to work despite their emaciated condition. [8] By December 1792 Toongabbie totalled over 696 acres (281.6 hectares) of wheat, barley and maize whereas Parramatta cultivation had dwindled to 316 acres (127.8 hectares). [9]

With Phillip's departure in December 1792, Lieutenant Governor Grose adopted a different agricultural policy. He discontinued centralised government farming, granted land to military and civil officers, officials and settlers, allotted the majority of the convict workforce to them, and encouraged them to raise cereal crops, to be purchased by the Commissariat Store. As the Toongabbie land was starting to show signs of exhaustion, it gave Grose the opportunity to alienate most of it and reassign the convict work force.

Governor Hunter arrived in September 1795 with orders to re-establish public farming. A large barn was completed at Toongabbie in December 1797: it was 90 feet (27.4 metres) in length with a floor capable of allowing eight or nine threshers to work concurrently. A large number of cattle were placed at the farm and thrived: it was hoped that their manure would revitalise the soil. [10] In August 1801, Governor Philip Gidley King advised the government that he had 50 men clearing land for a new Government Farm at Castle Hill to replace the worn-out Toongabbie farm. [11]

[media]The farm superintendents and assistant superintendents were Thomas Daveney, George Barrington, Richard Fitzgerald, Andrew Hamilton Hume and John Jamieson.

Land grants

The first land grants at Toongabbie were made to Thomas Daveney (100 acres/40.4 hectares), Andrew Hume (30 acres/12 hectares), Charles Grimes (100 acres) and John Redmond (60 acres/24 hectares) by Grose in 1794. Later grants, ranging between 25 and 160 acres (10 to 64.7 hectares), were made each year until the end of the century.

In June 1798 Hunter was in Parramatta surveying land near Mount Wilberforce (West Pennant Hills) where he found good, open, well-watered land to settle the Tahitian missionaries and the Barwell settlers. Andrew McDougal and John Smith of the Barwell preferred the option of 150 acres (60.7 hectares) each at Toongabbie. [12]

Nothing remains of the site of the 'township' today other than the possible remains of some steps cut into the sandstone bank on the north side of the creek, the remaining 300 acres (121.4 hectares) having been granted by sale mostly to George Oakes, son of missionary Francis Oakes.

The settlement however gradually prospered into a respectable farming community and township at the junction of Old Windsor and Fitzwilliam roads, with a Methodist church, a fire station, post office, primary school and a produce store. The area regarded as the township was gradually 'lost' with the widening of Old Windsor and Fitzwilliam roads and the development of a more modern township adjoining the railway station.

Rail and the new town

With the [media]opening of the Parramatta-Blacktown extension of the railway on 26 April 1860, it was only a matter of time before a platform was opened to service the rural suburb of Toongabbie to the north. There was a gradual relocation of public utilities towards the town that grew up beside the station, mainly on the south side.

The post office had several changes between the two Toongabbie locations until it was firmly established as Toongabbie Post Office at the 'new' Toongabbie in December 1960, whereas the first school named Toongabbie began in April 1886. Other schools were established at Toongabbie East (1966) and Toongabbie West (1967).

[media]The name Old Toongabbie for the suburb alongside the creeks came into use to distinguish the older part of the suburb from the suburb that grew around the 1880 railway station.

The Old Windsor Road that ran from Parramatta to the Hawkesbury once bisected the convict farm. Once notorious for Toongabbie Creek flooding across the road, today the road is a six-lane highway and the transport artery to the Hawkesbury. A motorway from the city joins Old Windsor Road at Abbot Road. These roads allow traffic to flow to the populous new suburbs of the western Hills District.

In 1996 the Geographical Names Board changed the spelling of Toongabee Creek to the standard form of Toongabbie to conform to other spelling. Various meanings have been attributed to the word, 'the junction of two creeks', 'meeting of the waters' and 'near the water'. Doris Sargeant in her Toongabbie Story refers to John Sternbeck, a McDonald River settler, who in his reminiscences suggested the meaning as 'land of the hills near the water'. Allowing for the spectacular flooding in the vicinity of Oakes Road and Johnston's Bridge that occurs periodically, Sargent suggests perhaps 'meeting of the water'.

Toongabbie, [media]once part of the Shire of Blacktown, was amalgamated into Parramatta in 1948 by a State Government anxious to consolidate municipal boundaries.

Toongabbie Primary School, in Fitzwilliam Street, opened in 1886 and another school, Toongabbie East, commenced in January 1966. A new Anglican church of St Mary was built in 1889 but demolished and replaced by new buildings in 1994. The Marist Brothers once conducted a seminary and farm on land that was previously the western part of the convict farm.

References

D Sargeant, The Toongabbie Story, Sydney, Toongabbie Public School Parents and Citizens Association, 1975

Notes

[1] J Brook and J Kohen, Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1991, pp 3–5; J Kohen, The Darug and their Neighbours, Darug Link in association with Blacktown and District Historical Society, Blacktown NSW, 1993 p 28; J White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1962, p 129

[2] J Brook and J Kohen, Parramatta Native Institution and the Black Town, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1991, pp 60, 356, 369, 371; J White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1962, p 128

[3] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 1, pp 146; W Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, Library of Australian History in association with the Royal Australian Historical society, Sydney, 1979, p 249; F Campbell, 'The Rose Hill Government Farm', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 12, 1926, p 360; 'Plan of Rose Hill Settlement', ML BT 36 plan 18; J White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1962, p 128

[4] The first recorded mention of the name Toongabbe appears to be by Collins in July 1792. Phillip officially named Rose Hill 'Parramatta' on the King's birthday in June 1791, recording it first on 5 Nov 1791, Historical Records of New South Wales, p 539

[5] 'The Plan of Toongabby', 1792, Public Record Office, London, CO 700, 5

[6] Paul-Alan Johnston, 'The Phillip Towns: Formative Influences in Towns of the NSW Settlement from 1788 to 1810', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 1985, pp 266, 369

[7] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 1, p 346 and editor's note to illustration, p 525; D Sargent, The Toongabbie Story, Sydney, Toongabbie Public School Parents and Citizens Association, 1975, p 18

[8] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 1, vol 1, p 181

[9] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 1, pp 207, 209

[10] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 2, pp 5, 52

[11] King to Portland, 21 August 1801, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 4, p 462; 1 March 1802, p 714

[12] D Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, Sydney, AH & AW Reed with the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 2, pp 83, 258

.