The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Jews

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Jews

With the arrival of around 16 Jewish convicts on board the First Fleet in 1788, a rudimentary Jewish community was present from the beginning of European settlement in Sydney. [1] However, it took time before formal communal structures were created. [media]The first developments related to burial, because correct interment of the dead is one the most important religious imperatives a Jewish community must observe. From 1817, Jews in Sydney came together to perform Jewish burials. In 1832 a section of Devonshire Street Cemetery (where Central Station stands today) was consecrated as Jewish.

Free settlers

[media]Until the late 1820s only a few free Jewish settlers arrived in Sydney. In 1828 Phillip Joseph Cohen arrived with permission from the British Chief Rabbi to carry out Jewish marriages and, in 1832, a formal community was established with Joseph Barrow Montefiore as its first president. [media]Since nearly all of these early settlers came from England, they transposed their English pattern of Jewish practice to Australia.

Most Jews in the colony were shopkeepers, and their presence in George Street was strongly felt. They were the drapers and the auctioneers. Barnett Levey established the first theatre in Sydney, the Theatre Royal, located where Dymocks bookshop stands in 2008.

One of the Jewish emancipists who started as a shopkeeper was Moses Joseph. He became a very successful trader, developing a fleet of 15 vessels. In 1852 he was the largest exporter of gold in the colony. In 1832, whilst still a convict, Moses Joseph married free settler Rosetta Nathan, who travelled from London for this purpose. Theirs was the first official marriage performed by PJ Cohen. [media]By 1840, Joseph was wealthy enough to purchase a block of land in York Street to build a synagogue. [2]

Joseph's achievement was just one of the many success stories. This success was due to the fact that many of the Jewish convicts were literate; that networks were established between them and free settlers; and that Jews were highly proficient in their traditional occupations as shopkeepers, and in commerce.

In 1844, the Sydney congregation moved to their first purpose-built synagogue in York Street. Built in the Egyptian style, it was funded partly by the Jewish community with some donations from Christian supporters and a government subvention.

Development of the Great Synagogue

In the mid-nineteenth century, 40 per cent of the colony's Jews lived in rural areas of New South Wales, but for most it proved too difficult to maintain a Jewish lifestyle and they either assimilated or moved to Sydney. [media]In the 1870s, under the leadership of Reverend Alexander Davis, the two Sydney congregations in York and Macquarie Streets united and in 1878 the Great Synagogue was consecrated. For 35 years from its inception in 1878 it was the only synagogue functioning in Sydney. Also referred to as the 'cathedral synagogue', it remains in active congregational use as well as being one of Sydney's historical landmarks.

Eastern European migration

The pogroms instigated by Tsar Alexander III of Russia during the 1880s led to a mass exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe. Most of these Jews had lived in shtetls, small Jewish villages almost completely isolated from outside influences. Although many of them spent time in Britain before arriving in Australia, they found the cold formality of the established and well-assimilated Anglo-Australian Jewish community alienating.

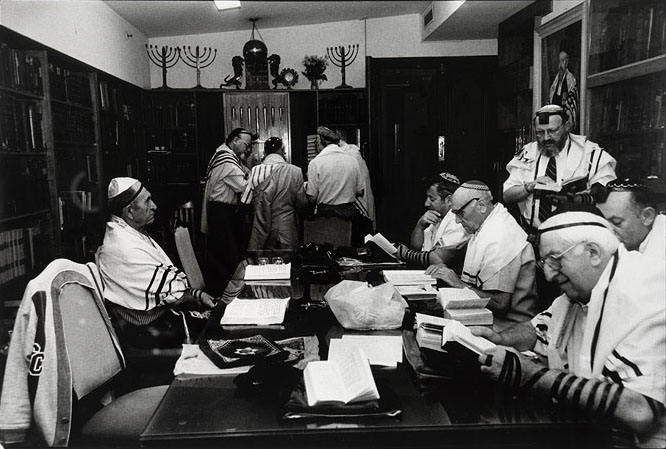

The [media]new migrants settled in Darlinghurst, Surry Hills, Paddington, and Newtown, and later some moved to Bondi and Bankstown. Initially, they formed small religious prayer groups ( minyan, or the ten men needed for formal Jewish prayer). The first was in Druitt Street in the 1880s. Later, the Baron de Hirsch minyan was formed in Darlinghurst, and small groups met for prayer in Newtown. The first suburban congregation to build its own synagogue was in Bankstown in 1913; the Newtown Synagogue opened in 1918 and the Eastern Suburbs Central Synagogue, initially formed in Surry Hills in 1912, opened its synagogue in Bondi Junction in 1923. The newcomers also introduced Zionist ideas to Sydney Jewry, which until the 1890s was largely unaware of the stirrings of Jewish nationalism in Europe.

Eastern European migrants also brought with them a love of Yiddishkeit (Jewish culture based on the Yiddish language). However, when Rabbi Isadore Bramson delivered a sermon in Yiddish in 1901 he was strongly criticised by the established community at the Great Synagogue. [media]Rabbi Francis Lyon Cohen, who was appointed as the senior rabbi at the Great Synagogue, and served in that position until his death in 1934, continued to be highly critical of Zionism and to make derogatory comments about the Yiddish language. Unlike Melbourne and Brisbane, Sydney did not develop organisations that sponsored the use of Yiddish or Yiddish theatre.

The golden age

By the end of the nineteenth century, Jews had become a well-established minority with identifiable settlement and occupational patterns, making them more visible than their 0.5 per cent of the total population may have predicted. Although there was some anti-Jewish prejudice, most enjoyed success in economic, political and social life. Observers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, remarked on the high proportion of Jews active in Sydney's public life. An article published in 1922, entitled 'One Hundred Years of Judaism in Australia', claimed:

'Every country has the sort of Jews it deserves.' Berthold Auerbach made this epigram about his own race and if there is any truth in it, New South Wales has deserved exceedingly well. In every branch of our activities since the earliest times, members of the Jewish community have taken a large and distinguished part. [3]

Sydney Jews were a very acculturated group, who spoke English and were so well integrated that 'their outward manner was hardly distinguishable from [non-Jewish Australians]'.

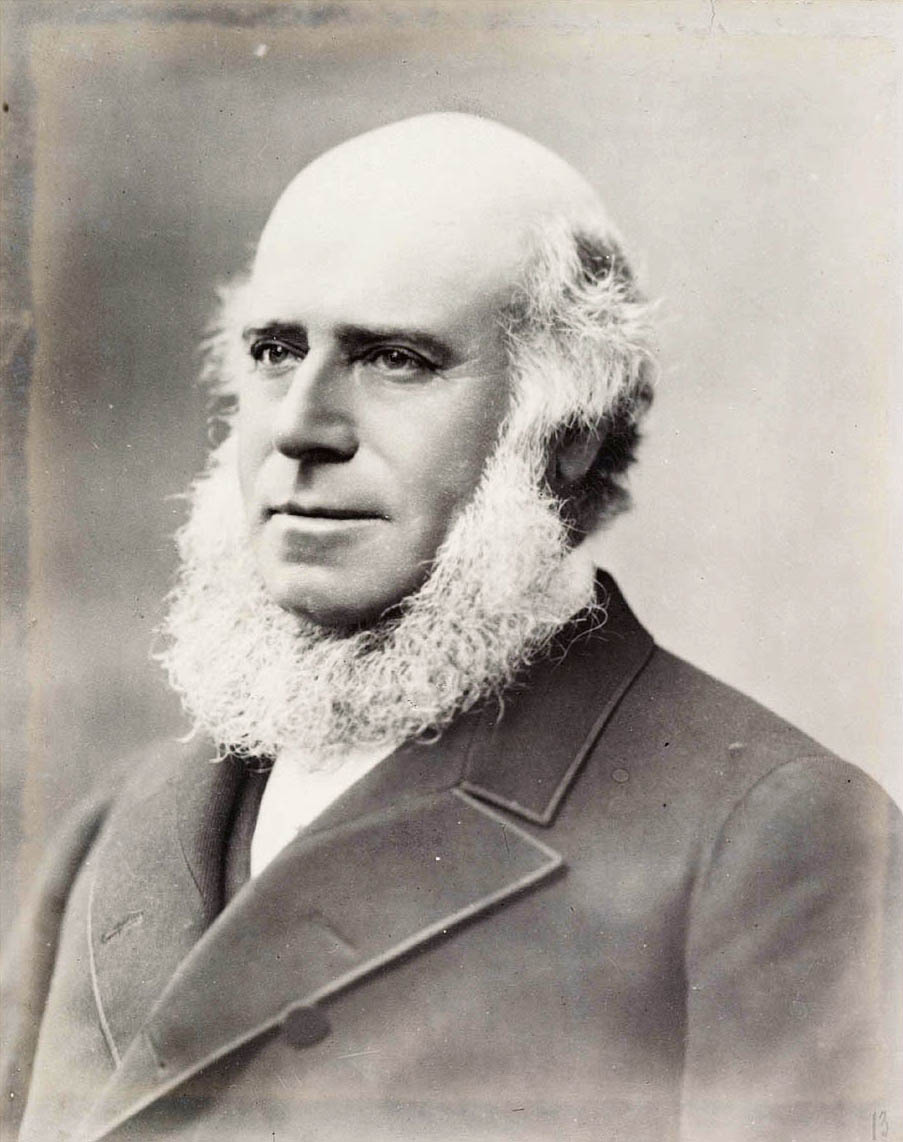

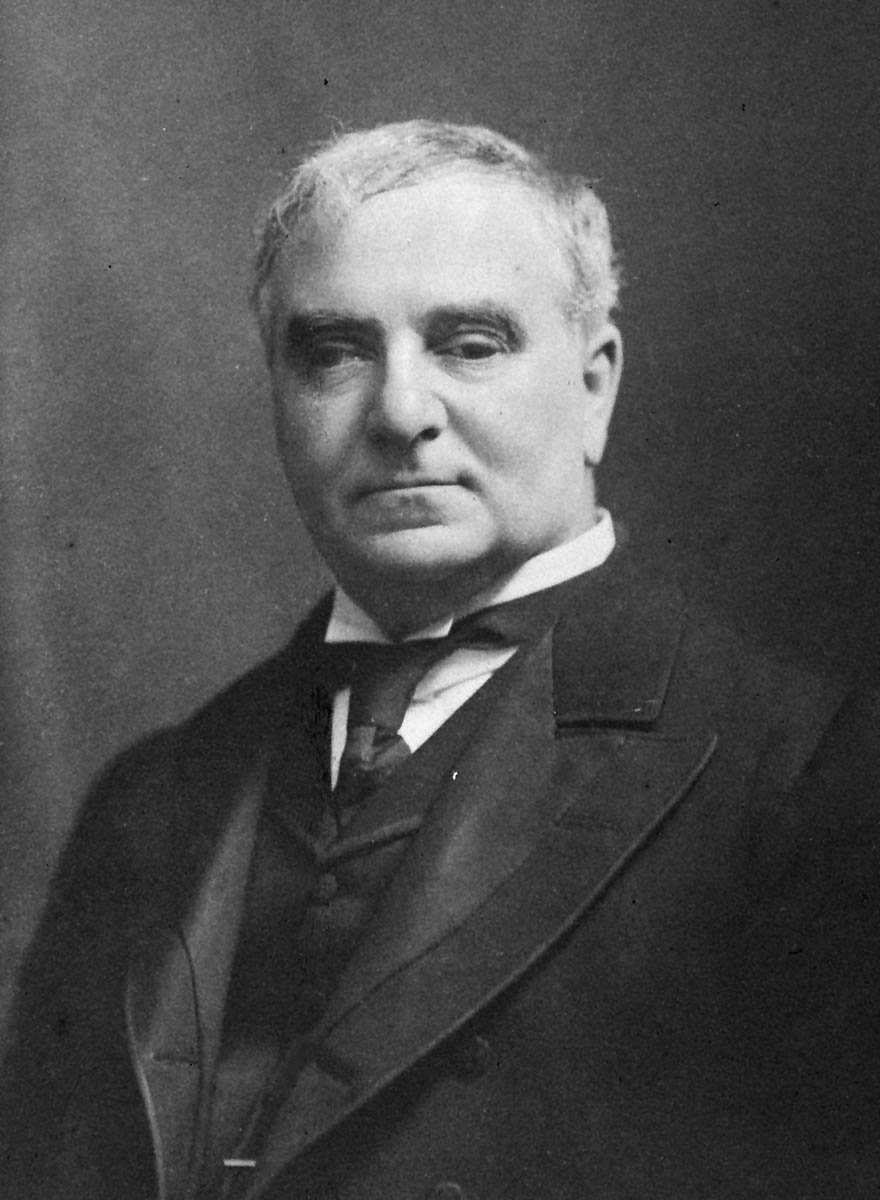

[media]From 1859, when Saul Samuel was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, the number of Jewish parliamentarians in both the lower and upper houses increased. Saul Samuel was knighted and went on to serve as New South Wales Agent-General in London from 1880 to 1889, after having been elected as the first president of the Great Synagogue.

[media]Sir Julian Salomons, another prominent Jewish politician, succeeded Samuel as Agent General in London. Salomons served for various periods from 1870 to 1889 in the Legislative Council, and was Solicitor-General and vice-president of the Legislative Council. In 1886 he was appointed Chief Justice of New South Wales, but resigned after a few days because Sir William Windeyer, a leading figure in Sydney, accused him of 'always breaking down mentally'. [4]

There were many other leading Jewish figures in the New South Wales parliament. In 1917, the Legislative Assembly did not sit on Yom Kippur (the Jewish Day of Atonement) because the Speaker, John J Cohen, and the Deputy Speaker, Sir Daniel Levy, were both observing Jews. [media]In the 1930s, Ernest S Marks was elected as Sydney's first Jewish Lord Mayor, and a number of other Jews were active on local councils.

Sydney's Jews developed a specific demographic pattern, which has continued to distinguish the community. The shift to suburban areas reflected a move up the economic ladder into the merchant and professional classes during the early twentieth century. In Sydney in the 1870s, 89 per cent of the Jewish population was concentrated in the Town Hall area. By 1901, 77.6 per cent had moved to Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Paddington, Glebe and Newtown, 5.4 per cent to the working-class and lower-middle-class suburbs of the south-west, 11 per cent to the residential suburbs of Woollahra, Waverley and Randwick, and 6 per cent had scattered in other areas. By 1921, 33.9 per cent of Sydney Jewry was living in the eastern suburbs, and this trend continued in the 1930s. [5]

Refugee migration before World War II

Nazi persecution led to the arrival of 8,000 Jewish refugees before World War II, and the beginning of a period of transformation for the Australian Jewish community, with around 5,000 settling in Sydney. In 1940, the infamous ship Dunera brought another 2,000 internees. The 'Dunera Boys', as they became known, had sought to escape Nazi persecution by migrating from Europe to England. However, once war broke out they were classified as 'enemy aliens', interned and transported to Australia. [6]

Mainly from the professional and business classes of central Europe, prewar refugees quickly moved up the economic and social ladder. They sought to strengthen and diversify religious and communal life. [media]They revitalised the newly established and more orthodox synagogue Bondi Mizrachi, but also introduced Reform (Progressive) Judaism with the foundation of the Temple Emanuel in Woollahra in 1938. The Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the New South Wales Board of Deputies were formed, and sports such as soccer were popularised through social networks at Bondi's Hakoah Club. Together with other European migrant groups, prewar Jewish migrants brought a continental flavour to Sydney's art, music and theatre scenes and to its cuisine.

Postwar migration and transformation of the community

The end of World War II consolidated these significant changes for Australian Jewry. The community almost doubled as a result of postwar migration, and by the 1950s over 60 per cent of Sydney's Jewry was foreign-born. Most who came were Holocaust survivors; others left India following Independence in 1948, or escaped the Hungarian Revolution or were expelled from Nasser's Egypt, in 1956.

Increased migration stimulated the Jewish consciousness of the established community. Again this resulted in changes to the community's organisational structure and religious life. Jewish education was further developed, as were Jewish cultural organisations along the lines of European and American models.

Despite this growth, popular and government hostility to Jewish immigration, epitomised by the enforcement of 'quotas' and the exclusion of Jews from official government immigration programmes, meant that Jews continued to constitute only 0.5 per cent of the overall population.

Sydney's changing cityscape

The period between 1938 and 1961 saw Sydney's Jewish population more than double as a result of European Jewish migration. In 1966, well-known theatre director Hayes Gordon summed up the impact:

It would seem that Australia has much to be thankful for in the dislocation of people as a result of Hitler's war. While it was undoubtedly painful perhaps beyond measure to witness great cultures burnt with their books, yet so many Europeans were able somehow to salvage a measure of this cultural wealth, and bring it with them to their new home on this vast Pacific island. They came at a time when Australia was crying out to find itself. And coming with a fresh outlook, it was often the newcomer who saw what needed to be done, and how. [7]

The contributions of the Jewish refugees were in the realms of business; the professions, particularly science and medicine; the arts, including music, theatre and painting; and general culture, including restaurants and delicatessens.

Sydney's cityscape changed significantly due to this 'dislocation' of the Jews from Europe. A number of Jewish refugees and survivors contributed significantly to Sydney's urban landscape in the areas of architecture and property development. [media]They included architect Harry Seidler, who was central in developing a modernist approach in Sydney; property developer Sir Paul Strasser; Frank Lowy, who developed the Westfield shopping centres, initially in partnership with fellow survivor, Hungarian John Saunders; Ervin Graf, who developed Stockland; and Harry Triguboff, whose Meriton apartments have provided inexpensive apartment living in Sydney, not without controversy. Sydney's second Jewish Lord Mayor, Leo Port, represented the Civic Reform Movement.[media] As Lord Mayor he brought to Sydney European sensitivities concerning civic spaces, which resulted in the creation of Sydney Square, the pedestrianisation of Martin Place and the redevelopment of the Queen Victoria Building. However, many of his projects did not reach fruition due to opposition from the green movement and bans introduced by the Builders Labourers Federation. Port died in office in 1978, with his name under a cloud – he was considered by some to be too close to developers and accused of financial impropriety through two finance companies linked to the acquisition of urban land during the 1974 financial crash. [8]

Kings Cross was also influenced by Jewish personalities. Developer Frank Theeman had major plans but became embroiled with a great deal of controversy due to the murder of journalist and Mark Foy department store heiress, Juanita Nielsen, who was campaigning against his development. Abe Saffron, known as 'Mr Sin', owned many of the pubs and bars in the Cross and was accused of being involved with organised crime and prostitution. Saffron was eventually arrested and imprisoned for tax evasion. In a new biography, his son has claimed that he was directly involved in Nielsen's murder, and that it took place in the Carousel Club, which Saffron owned.

Impact of the 1967 Six Day War

In June 1967, the Six Day War erupted between Israel and its neighbours Egypt, Jordan and Syria. Within a week it had changed the geography of Israel, with significant repercussions across the Jewish world. Assessing Australian Jewry's reactions to these momentous events, Professor Ronald Taft commented that

whatever the explanation, the June crisis obviously had a fundamental effect… and its repercussions are likely to be felt for a long time to come. [9]

Professor Taft's prediction proved correct, since the Six Day War had a galvanising impact on Jewish awareness throughout Australia. A 1970 survey conducted in Sydney by Professor Sol Encel showed that the war resulted in an intensification of feelings of Jewish identity, which had a long-term effect on the self-perception of diaspora Jewry. [10]

Another major result was the formation of the Joint [Jewish] Communal Appeal (JCA) which, without doubt, has changed the face of Sydney Jewry. A former president of the New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies, Gerry Levy, stated that the JCA has become 'the lifeblood of the community'. [11] Consisting initially of 10 organisations, today it includes 19 Jewish organisations in Sydney, representing the educational, welfare and community sectors of Sydney Jewry.

The impact of the 1967 war also influenced the growth of Jewish day schools in Sydney. Moriah College, the first Jewish day school in the twentieth century, was founded in 1942, but it developed very slowly. In 1965 it had only 150 students and its high school, opened in 1960, was experiencing severe problems. Masada College, founded on the North Shore in 1966, was also initially a very small school. From 1970 on, however, the schools grew rapidly and three new schools were formed: Mount Sinai College, Emanuel School and Yeshiva College. In 2005, Yeshiva College split as a result of an internal dispute. Yeshiva College was renamed Kesser Torah, and since then a Yeshiva Primary has been re-established in Flood Street, Bondi, in 2008. Around 55-60 per cent of Jewish children attend Jewish schools. Those attending government schools are serviced by the New South Wales Board of Jewish Education, now called Academy BJE, which teaches Hebrew as a community language in a number of primary and high schools in the eastern suburbs and on the north shore.

New waves of migration

Sydney Jewry is one of the few Jewish diaspora communities that have been growing in size – almost entirely due to immigration from Russia, South Africa and Israel.

From 1967 the continuing denial of human rights in the USSR caused many Soviet Jews to apply for migration to the West. Those who managed to migrate to Australia settled mainly in Bondi or in inner-city government housing. The Australian Jewish Welfare Society (now JewishCare) sought to ease their integration into Australian society by running English classes for Russian Jews and organising social activities, especially for the elderly in the community.

With South African Jewish migration, noticeable increases occurred following the Sharpeville riots of 1960, the Soweto uprising of 1976, and the period of the collapse of apartheid in the late 1980s and 1990s. Many left South Africa prior to 1989 due to their unease with the government policy of enforced racial discrimination; others, particularly more recently, left to escape the escalating crime and violence. Fifty-eight per cent of all South African Jews have chosen to settle in Sydney, compared with 26 per cent in Melbourne, and 13 per cent in Perth, with the remainder settling in Brisbane and Adelaide. Initially South Africans settled in and around St Ives, where they could buy larger homes like those they had been accustomed to in South Africa, but at lower prices than in the eastern suburbs.

Many of the Israelis who come to Australia, attracted by the way of life they discover while travelling, envisage their stay here as a temporary one. According to a survey conducted in 2005, about 27 per cent of Israelis said they chose Australia as it offered a better future for family; 25 per cent said better climate, lifestyle, or political stability; 21 per cent did not feel safe/secure; and only 13 per cent said to escape conflict/war. [media]Most Israelis, who are accustomed to apartment living, also have settled in Bondi, although some live away from the areas of Jewish concentration. [12]

Expansion of the community from the 1980s

With increased immigration since 1980, Sydney Jewry has experienced a further expansion of synagogues, mostly in the area around Bondi, with a further 12 congregations being formed, as well as a number of smaller prayer groups.

Much of this expansion has been due to growth of the Habad movement, a sect of the Hassidic ultra-orthodox group also known as Lubavitch, after the Russian town where the movement was centred in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From 1967, the Yeshiva in Flood Street came under Habad leadership, and in the 1980s it established a rabbinical training college. Most of the congregations in Sydney are led by Habad rabbis, even if they do not espouse the Habad philosophy.

[media]The Temple Emanuel in Woollahra has also experienced growth and diversification and in 2007 was renamed Emanuel Synagogue. Representing a more pluralistic approach to Judaism, this campus now houses three different movements – Progressive, Conservative and Renewal – all of which are alive in Sydney.

References

Suzanne D Rutland, Jews in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2005

Notes

[1] JS Levi and GFJ Bergman, Australian Genesis: Jewish Convicts and Settlers, 1788-1850, 2nd edition, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002 (first published 1974)

[2] John S Levi These are the Names: Jewish Lives in Australia 1788–1850, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2006, pp 369–71

[3] Sunday Times, 24 December 1922

[4] MZ Forbes, 'Sir Julian Salomons, 1835–1909', Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal, vol 13, no 3 1996, pp 367–94

[5] Charles Price, 'Jewish Settlers in Australia', Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal, vol 5, part 8, 1964, pp 392–94

[6] Konrad Kwiet, '"Be Patient and Reasonable": The Internment of German-Jewish Refugees in Australia', in Konrad Kwiet and John A Moses (eds), 'On Being a German-Jewish Refugee in Australia', special issue, Journal of Australian Politics and History, vol 31, no 1, 1985, pp 61–77

[7] Viennese Theatre, Sydney, 1966, quoted in Suzanne D Rutland, Edge of the Diaspora: Two Centuries of Jewish Settlement in Australia, Brandl & Schlesinger, Sydney, 2001, pp 279–80

[8] Shirley Fitzgerald, 'Port, Leo Weiser (1922–1978)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 16, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002, pp 18–19

[9] Ronald Taft, 'The Impact of the Middle East Crisis of June 1967 on Melbourne Jewry: An Empirical Study', The Jewish Journal of Sociology, vol 9, no 2, 1967, p 261

[10] S Encel, BS Buckley and JS Schreiber, The New South Wales Jewish Community: A Survey, School of Sociology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 1972

[11] Interview with Gerry Levy, conducted by John Temple, Sydney, 27 December 2006, quoted in Suzanne D Rutland, Triumph of the Jewish Spirit: 40 Years of the Jewish Communal Appeal, Jewish Communal Appeal, Sydney, 2007, p 29

[12] Suzanne Rutland and Antonio Carlos Gariano, 'Survey of Jews in the Diaspora: An Australian Perspective', unpublished report commissioned by the Jewish Agency Research and Strategic Planning Unit and Department for Jewish Zionist Education, p 17; Suzanne D Rutland, Jews in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2005, pp 144–45

.