The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Housing Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Housing Sydney

Greek culture did not begin with the Parthenon, it began with a white-washed hut on a hillside. [1]

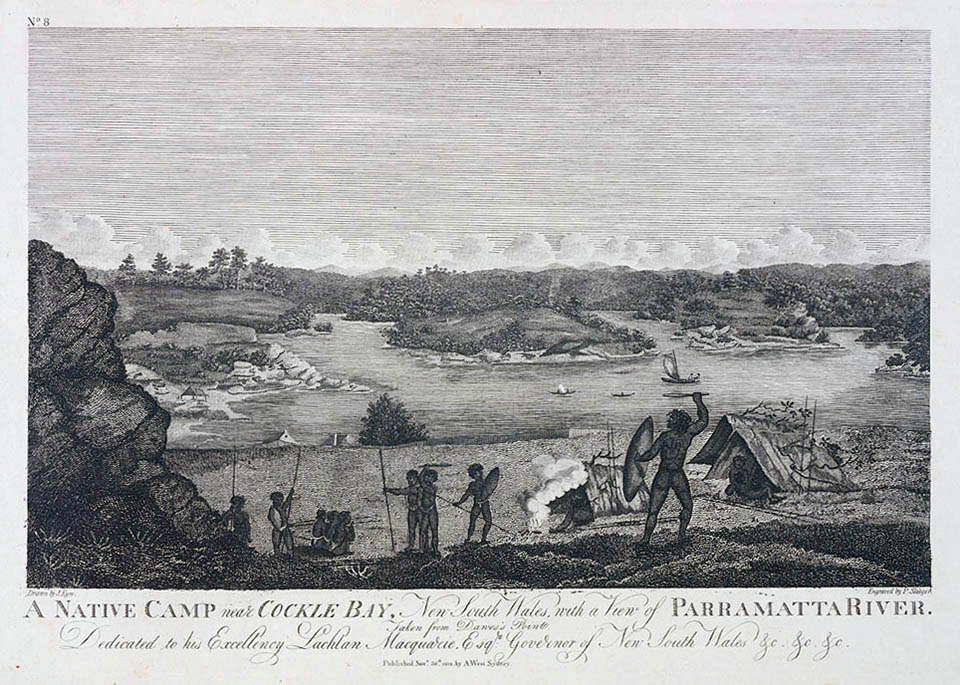

Sydney is not just the Opera House and the Harbour Bridge, but the homes and lifestyles of its residents, past and present. [media]The Sydney region has provided homes for people for many thousands of years, from the more or less temporary shelters of its Aboriginal residents, through early colonial wattle-and-daub huts to Georgian cottages, squalid row housing, Victorian terraces, Edwardian and Californian bungalows, shacks, shanty towns, serviced apartments, flats, weatherboard and fibro cottages, caravan parks and most recently to McMansions and the high rise steel and glass towers of the twenty-first century. [2] But housing is not simply houses – it is the process by which houses come to be built and occupied, and thus it is one of the most important processes that form a city.

Sydney's first housing

[media]Local materials – including pise, slab, timber thatch and wattle-and-daub – determined the construction of Sydney's first houses. A little later, housing was also made of brick and of Sydney's famous sandstone. Climate and the availability of land influenced building practices and styles as did the cultural baggage the colonists brought with them. Sydney was also a penal settlement. The local environment, both natural and social, mediated the various imported European tastes and desires for a home in early Sydney.

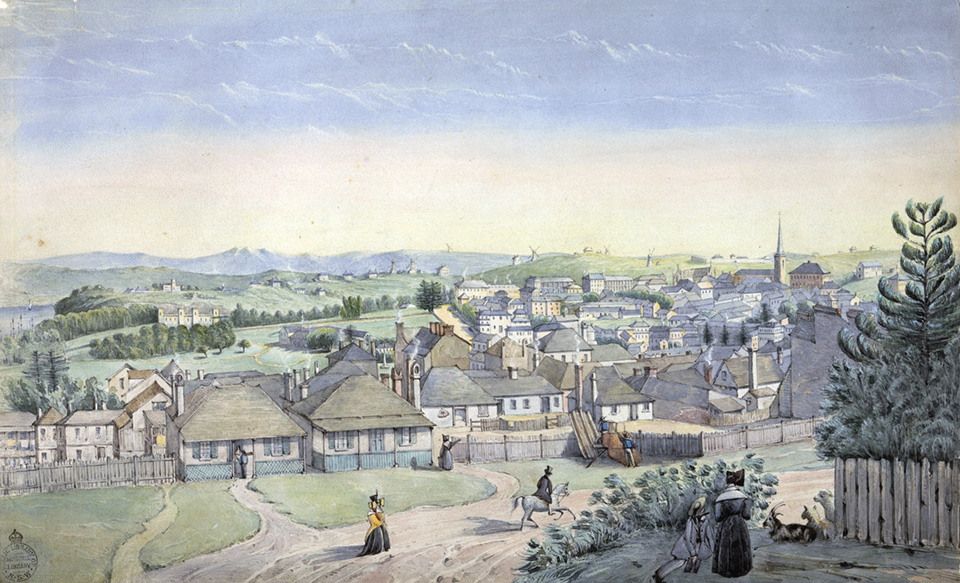

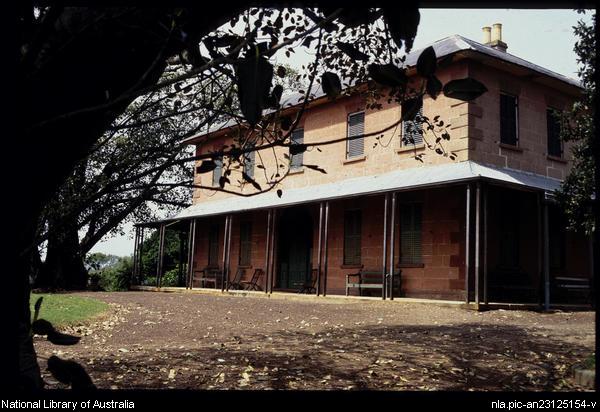

[media]Housing was also, and remains, a symbol of social and economic status. Well-heeled colonists imitated housing styles from Britain, such as villas, associating themselves with the dominant classes 'back home'. The respectable classes emulated the choice of housing of their counterparts at home. During the nineteenth century, pattern books aided this process by providing examples of ideal vernacular architecture. Poorer people rented housing from landlords. Some of the destitute were accommodated in places such as the New South Wales Benevolent Society asylum built with government funding at the corner of Devonshire and Pitt Streets in 1821.

Sydney housing now

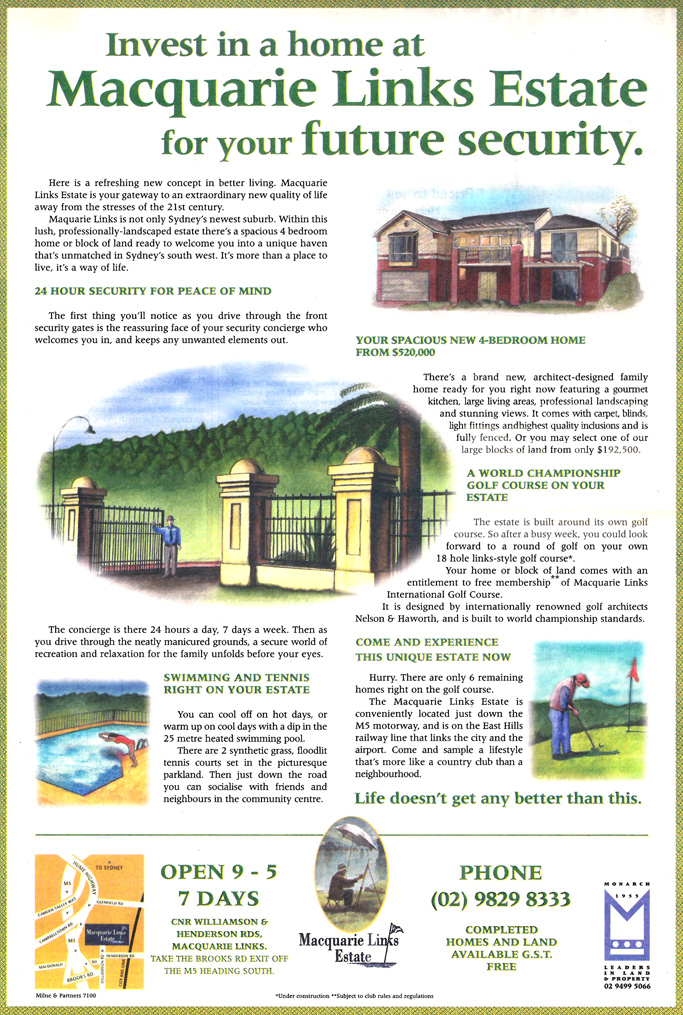

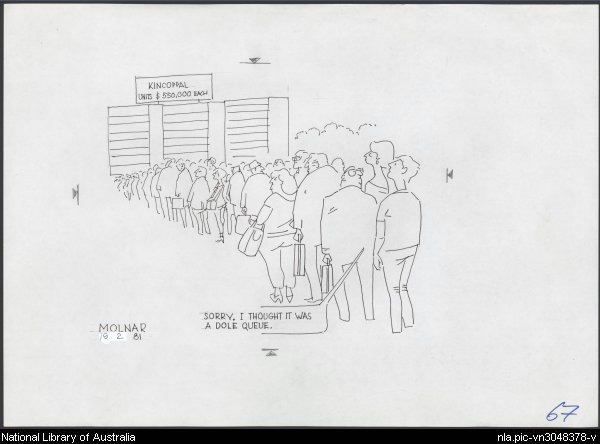

In an international context, Sydney ranks as one of the most expensive housing markets in the world and has for some time. In August 1998 Sydney's Sun Herald reported that 'Only the rich can afford to buy a house within 25 kilometres of the city.' [3] This article featured figures showing that houses in areas close to the city centre, and especially to its north and east, were between two and four times more expensive than the Sydney median, while those areas where prices were below the median all fell far to the west and south.

[media]Real estate prices are a frequent and prominent theme in the Sydney media, just as they are a particular obsession for the many people attempting to secure a stake in the Sydney housing market. All major Australian cities are deeply polarised by housing costs, but the low density and large area of Sydney as well as its inimitable harbour and particular topography ensure that housing processes and outcomes in Sydney are a key contributor to great wealth for some and enduring poverty for others.

The essential nature of housing as shelter, the central part it plays in our personal aspirations and community identity, together with the durability of houses themselves, mean that housing processes and products provide an invaluable contribution to understanding the city. The form, location and condition of its dwellings are a key feature of Sydney, reflecting its historical development, household and social structure, economic conditions and response to climate. Housing as a process involves household status and aspirations and social institutions, including local state and federal government, banks, builders, and welfare agencies.

Four closely interacting aspects of Sydney's housing provide indispensable insights into the city's social makeup, its economic foundations and cultural identity.

- Types – what types and sizes of structures house Sydney people, and what condition are they in?

- Tenure – how do Sydney people secure and pay for their homes?

- Costs – how much do people pay to live in Sydney?

- Location – what is the relationship between place and each of these other dimensions?

Unfortunately, as in most large metropolises around the world, at any given time a proportion of Sydney's residents are unable to secure housing of any kind. For shorter or longer periods and for personal or structural reasons, some individuals and families remain homeless. This issue is also discussed below.

Types: from the quarter acre block to apartment living

[media]The stereotypical Sydney house is either a narrow two-story Paddington terrace (or row-house), or a double-fronted brick veneer (or possibly 'fibro') bungalow on a large block in the suburbs. While each of these certainly exists in abundance, Sydney's housing types are changing both in form and balance.

In 2006 approximately 1.5 million dwellings housed Sydney's 4.1 million residents. [4] Almost 940,000 of these were detached houses and a further 180,000 were semi-detached row or terrace houses. Separate detached houses make up just over 61 per cent of Sydney's housing (compared with 75 per cent for Australia as a whole) but this proportion is slowly falling across the city.

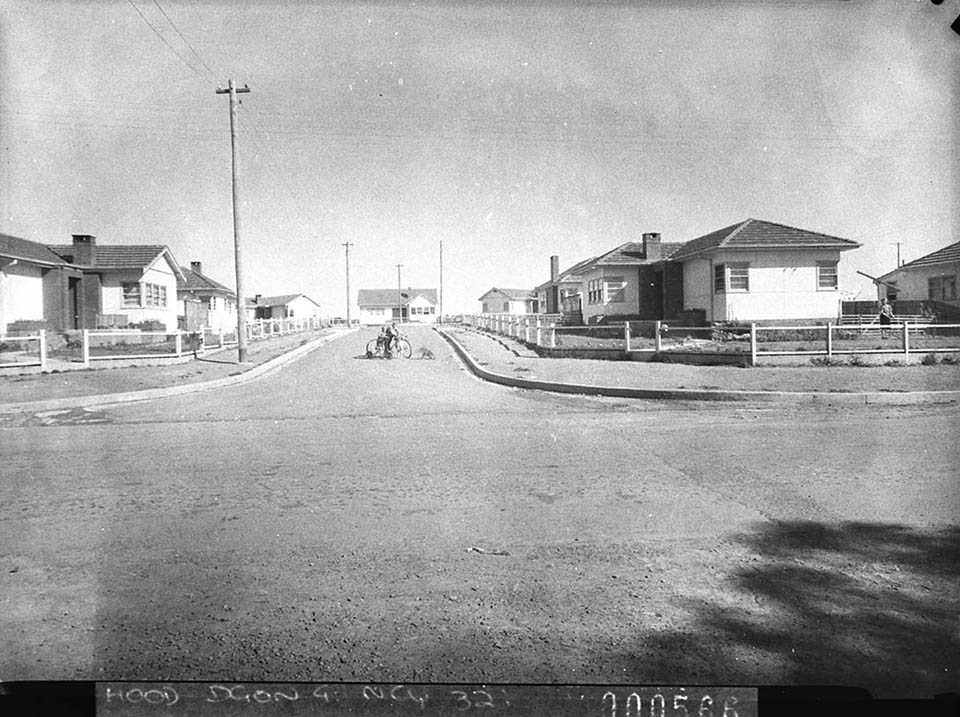

Terrace and row housing is most prevalent in inner-city areas up to about 8 kilometres from the city centre, developed before the wide spread of car ownership. While the legendary 'quarter-acre block' (1011 square metres) has always been an exaggeration for most Sydney households, housing blocks of 500 square metres and more have dominated housing development in the middle and outer ring suburbs developed since World War II. [media]However, under environmental and economic pressures, and in response to the increasing prevalence of smaller households, the last two decades have seen an accelerating trend towards denser multi-unit apartment buildings, known in Sydney as 'home units'.

Increasing demand for smaller dwellings closer to urban amenities, combined with changes to planning laws designed to address concerns over the environmental and economic costs of urban sprawl, resulted in a 30 per cent increase in the number of apartments in Sydney between 1996 and 2006, and this trend appears set to continue. However, while the number of apartments springing up in virtually all parts of the city is large, it still represents only a little more than a quarter of all dwellings.

While it is [media]widely accepted that housing density in Sydney must increase both to reduce our reliance on motor vehicles and to allow lower income households to have some chance of accessing jobs and the established physical and social infrastructure of the city, there is debate about whether current policies will achieve this.

Critics of the suite of policies known as 'urban consolidation' argue that the traditional preference of Australians for low-density suburbs is an important cultural value, which will not be removed without serious consequences. Some have claimed that the policy is simplistic and will consign lower income households to lower quality housing, rather than improve their situation. Meanwhile, the well-off in established suburbs are able to resist change and maintain their high levels of housing and urban amenity. [5] Studies showing that, despite the growth in numbers of higher density dwellings, the populations of inner and middle ring suburbs have not grown significantly, support this argument. Much of the demand for smaller dwellings in inner areas comes from new arrivals to Australia and overseas investors.

Thus separate houses continue to dominate suburban Sydney. [media]In western Sydney 80 per cent of all dwellings are separate houses, compared with 61 per cent in the greater Sydney area and 70 per cent across New South Wales. But despite this, or perhaps because of it, housing types and density in western Sydney are actually changing faster than in the city as a whole. From its lower base, the increase in the proportion of multi-unit dwellings in western Sydney has been much more dramatic than for the city as a whole – 157 per cent between 1981 and 2001, compared to 62 per cent across the Sydney area. [6]

Tenure: to rent or buy?

It surprises many people to learn that in the nineteenth century, Sydney was primarily a city of tenants. It was not until after World War II that home ownership became more common than renting in Sydney. Even today, Sydney has significantly fewer home owners than the national average.

Housing tenure refers to the legal and financial arrangements under which households occupy houses. The vast majority of Sydney households fall into one of two categories: owner occupiers and tenants. Owner occupiers may own their dwelling outright, or it may be mortgaged to a lender. Tenants may rent from private or public landlords. While many individual arrangements may fall outside this classification, the balance of these four basic groups helps to explain the state of Sydney's housing processes.

Tenure arrangements carry with them many differential costs, subsidies and rights. In Sydney, where the entry price for families seeking to purchase houses is the highest in Australia, there is often little choice for lower income households but to accept the insecurity of private rental or to join the long waiting list for public rental housing.

At the 2006 census, owner occupiers made up just over 60 per cent of Sydney households, which is about 4 per cent less than the proportion for Australia as a whole, while tenants comprise 30 per cent of households compared to 27 per cent nationally. This is partly explained by the cost of purchasing, and partly by the fact that Sydney has a higher than average proportion of non-permanent residents. Approximately 10 per cent of Sydney households have other tenure arrangements, or did not answer the question on the census form.

Notably, while the balance between owner occupiers and tenants has been relatively stable at 2:1 for many years, the proportion of Sydney owner occupiers who own their dwellings outright has dropped sharply since 2001 (from 40 per cent down to 30 per cent of all households). This is partly a consequence of more flexible banking arrangements which allow people to redraw mortgage borrowings to fund other things such as holidays, cars or renovations. However, the fall in outright owners in Sydney has been more marked than for the rest of Australia, reflecting the need for Sydney house buyers to borrow more money over longer periods. The proportion of households paying mortgages is also marginally higher in western Sydney, largely because of the higher proportion of younger families and first home buyers. This is why it has been described as Sydney's 'mortgage belt'.

Renting is perceived by most Sydney people as an inferior tenure, suitable only as a temporary arrangement for young singles, families saving to purchase, or for those with incomes too low or employment too insecure to qualify for a mortgage on a suitable dwelling. This reflects the relative insecurity of private tenancy in a city where most landlords own only one or a handful of residential properties and may choose to sell them to owner occupiers at any time in order to capture the capital gain on their investment. Under New South Wales law, tenants can be evicted without any cause so long as the landlord provides 60 days notice. Despite this, there are almost as many tenant households in Sydney as there are households with mortgages.

Sydney suffers a chronic shortage of rental housing, exposing tenants to uncontrolled rent increases, poor maintenance and even illegal discrimination (such as against disabled people or families with children) by some unscrupulous landlords.

Public housing

There are approximately 80,000 houses and apartments in Sydney let to qualified low-income tenants by the New South Wales housing department, and a further 8,000 by non-profit housing associations, cooperatives and welfare organisations. Public and community (social) housing tenants pay subsidised rents, assessed at 25 per cent of household income, and cannot be evicted without cause – although under new rules introduced in 2006, public housing tenants' eligibility to renew their leases can be reviewed at fixed intervals if their circumstances change.

Provision of subsidised social housing in Sydney has declined over the past decade both as a proportion of all households (from 6 per cent to just over 5 per cent) and in terms of the actual number of dwellings (a loss of around 1,000 housing units) and there are almost as many eligible people on the waiting list for public housing as there are existing houses. About half of the stock of public housing is located in 'estates' of 100 units or more, most of which are located in western and south-western Sydney.

In [media]the 1960s and 1970s, when the public housing system was expanding, these estates were developed for working families and played a major part in pioneering new housing development on Sydney's urban fringe. Thirty years on, with public housing allocations restricted to the neediest, they have become degraded and stigmatised, and in some cases are sites for social unrest. The housing department is currently embarking on some ambitious projects to redevelop run-down housing estates in parts of western Sydney through partnerships with private developers and housing associations.

Public housing providers are also facing a major challenge in attempting to adjust the balance of housing types in their portfolio to better meet the needs of the changing population. Around 70 per cent of metropolitan applicants require one- or two-bedroom accommodation although this type comprises just over half of the social housing stock, and up to 60 per cent of applications are for pensioner accommodation which makes up less than a quarter of Sydney's public housing stock. The public housing system now faces the challenge of progressively redeveloping and reconfiguring its stock of dwellings to better reflect the needs of its tenants and applicants. Projects designed to achieve this are currently being developed in Minto and Bonnyrigg, with many others to follow.

Costs: affordability in Australia's world city

The 2007 Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey [7] ranked Sydney housing as the seventh most unaffordable in its study, outranked only by markets on the United States' west coast. Sydney residents pay more for housing than those in London, and Sydney is by far the winner of the dubious honour of most unaffordable city in Australia. Demographia's index sets a notional 'affordability standard' of 3.0 which all major Australian cities exceed by at least a factor of two – but Sydney's score in 2007 was closer to three times the standard at 8.7.

The New South Wales government's Metro Strategy report (2006) [8] showed that while house prices declined as distance from the city centre increased, even at the city fringes (some 40 kilometres from the central business district) the median house price in 2004 was more than a quarter of a million dollars. This was up by around 70 per cent since 1994. Within five kilometres of the city centre, median prices were over half a million dollars which was eight to ten times the average annual wage for full-time workers.

The rapid decline in housing affordability in Sydney in recent decades is being driven primarily by the rise in the value of the land component in house prices. The 2004 National Summit on Housing Affordability [9] heard that while house building costs had increased modestly, the contribution of land value to house prices in Sydney had risen from 32 per cent to 60 per cent between 1977 and 2002. The price of land for housing results from a combination of factors, including development costs for newly released residential land, and tremendous demand for prime Sydney locations.

Serious concerns over the social equity implications of the high cost of housing in Sydney have dogged policy makers and housing and social justice activists for the last 15 years. In the early 1990s, the National Housing Strategy [10] defined those lower income households paying more than 30 per cent of their income for housing as suffering from 'housing stress'. The Ministerial Task Force on Affordable Housing in New South Wales [11] reported that of the 290,000 very low-income households in Sydney, about 50,000 (17 per cent) were paying at least this much for their housing. However, 94 per cent of the 38,000 very low-income tenants fell into this category, along with 55 per cent of the 20,000 very low-income purchasers. Full owners and public tenants experienced no housing stress, despite their very low-income status. Housing stress continues to be more prevalent in Sydney than anywhere else in Australia.

Location: harbourside mansions and fringe estates

[media]Sydney illustrates more clearly than any other Australian city the national issue of social justice in urban design. The north shore and the eastern suburbs have traditionally been the areas where housing is more expensive (and more expensively built), while the vast western and south-western suburbs have been seen as the dormitories of the working class, and the home of the humble timber-framed fibro or brick veneer cottage with a large backyard. [media]These stereotyped perceptions are compounded by a myriad of micro- and macro-locational factors such as availability of transport and other infrastructure and services, the housing needs of certain population groups such as students or families with young children, and the environmental amenity of particular areas.

The dynamic relationships between these have changed dramatically over time. For example, many areas close to the centre of the city, which a generation ago were seen as slums providing substandard, albeit cheap, housing for very low-income households, have been transformed into elegant and wealthy inner-city suburbs (examples include Paddington and Glebe). This is because of changing transport economics and a new urban environmental aesthetic. In recent years, as inner-city property prices have increased dramatically, 'gentrification' has begun to affect traditional working-class areas further from the city. Similarly, much of the previously undifferentiated low density suburbia of the middle-ring suburbs is rapidly being replaced by denser, multi-unit forms of housing, especially around major commercial centres and public transport nodes. This trend is, in part, a policy response to population and environmental pressures and their effects on the economics of land development.

[media]While the outer-ring suburbs in areas such as Campbelltown and Penrith generally remain the cheapest places to build new houses, newly 'corporatised' public utilities now emphasise an up-front 'user-pays' approach to infrastructure provision. The cost is now more likely to be loaded into land prices than taken on as public debt and spread across the city through rate payments. These areas are now favoured by more established households with greater equity and higher incomes, rather than first home buyers.

High land prices in well-serviced areas also mean that public housing is less likely to be found in areas where working families most want, or need to live.

The social problems created by rapid development of new residential areas on the metropolitan fringes have been a fact of life in Sydney for decades. In the 1960s and 1970s relatively cheap outer urban land provided an attractive alternative to state public housing providers faced with ever growing waiting lists, and to developers seeking to satisfy the enormous demand at the lower-priced end of the home purchase market. However, such rapid population increases, where a disproportionate number of new residents are low-income purchasers or public housing tenants, and often without due consideration of factors such as the prospects of developing local employment opportunities, have a massive impact on the social and economic infrastructure of the affected areas. Suburbs such as Macquarie Fields and Mount Druitt were originally developed as affordable and secure rental alternatives for working families but in recent years have become stigmatised by media and political attention given to them as centres of social disadvantage.

Homelessness

Visitors to the city often comment that they encounter far fewer homeless people on the streets of Sydney than in many major cities in Europe, Asia or the United States. This is an accurate observation, but reflects the fact that Sydney has an excellent network of shelters and emergency accommodation services. While 'rough sleepers' are not as obvious as in many other places, homelessness remains a significant and growing problem.

The annual number of requests for assistance to the Sydney Homeless Persons Information Service (an information and referral agency operated by the City of Sydney Council) more than doubled over the five years to 1998, when the service received 18,000 enquiries regarding approximately 26,000 homeless people. By 2003, enquiries to the service exceeded 30,000 and the number continues to grow.

Contrary to the common perception of homeless people as socially isolated or even mentally ill, 30 per cent of these calls (representing more than half of the homeless individuals) concern one- or two-parent families with children. Just over half the callers are women.

The most common reasons given for becoming homeless were interpersonal conflicts and family breakdowns (23 per cent), domestic violence (15 per cent), financial difficulty (15 per cent), and eviction, most often due to unpaid rent (10 per cent). Financial difficulty is a contributing factor in the homelessness of more than 36 per cent of the people concerned. About one third were living with friends or relatives, while about 3,500 (15 per cent) were living in a car, park, street, tent or other improvised dwelling. Most gave their last permanent accommodation as living with friends or relatives or renting in the private market.

The vast majority had only social security income, most commonly unemployment benefits, disability or sole parent pensions. Ten per cent suffered from psychiatric disabilities, while a further 20 per cent admitted to drug or alcohol problems either current or past. [12]

Despite the fact that most crisis accommodation services are located in inner areas only 14 per cent of the homeless people cited their last permanent accommodation in the inner-city area. Most homeless people called from, and last resided in, outer metropolitan areas. While around half were currently living in the inner city or inner suburbs, only a third gave this as their last permanent address. Only 6 per cent of homeless people called from country or interstate locations, but almost 30 per cent had come from previous permanent addresses outside Sydney, perhaps in the vain hope of securing more appropriate or affordable housing.

Those presenting as homeless to services such as those provided by the city council represent only the tip of the iceberg of housing insecurity and inadequacy. Census data shows thousands more living permanently in caravans and improvised dwellings, mainly in middle and outer suburbs such as Bankstown, Blacktown and Liverpool. According to official statistics, which may understate the number, caravans provide long term accommodation for approximately 1.5 per cent of families, but single parent families are almost three times as likely to be found living in them. While caravan park dwellers are not technically homeless, they rarely have the security of a tenancy agreement or lease of any kind, and often pay rents close or equivalent to those paid for flats in the same area. Despite this, at the last census, one-third of caravan park dwellers had been living there five years previously.

Ten years ago, Frank Stilwell suggested that

the concept of 'global city' or 'world city' … can be interpreted as a means of trying to legitimise what are for many people painful economic-social dislocations. [13]

There is no doubt that Sydney is now a world city, but for those seeking to make their home here, Sydney's ascent into the global housing and property markets has definitely made life more difficult.

Notes

[1] Herbert Read, The politics of the unpolitical, Routledge, London, 1946

[2] J Archer, The Great Australian Dream: The history of the Australian house, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1996

[3] Andrea Dixon, 'Houses in City a Bit Rich', The Sun-Herald 16 August 1998

[4] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Sydney Statistical Division

[5] Patrick Troy, The Perils of Urban Consolidation: A Discussion of Australian Housing and Urban Development Policies, Federation Press, Leichhardt NSW, 1996

[6] Urban Frontiers Program, Western Sydney Social Profile, University of Western Sydney and Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils, Blacktown NSW, 2002

[7] Demographia, 3rd Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, 2007, www.demographia.com/dhi-ix2005q3.pdf

[8] Sydney Metropolitan Strategy, New South Wales Department of Planning, NSW Government Metro Strategy 2006, www.metrostrategy.nsw.gov.au/dev/uploads/paper/housing

[9] Marion Powell and Glenn Withers, 'National Summit on Housing Affordability: Resource Paper', National Housing Alliance, Canberra, 2004

[10] National Housing Strategy, The Affordability of Australian Housing (Issues Paper No 2), Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra, 1991

[11] Ministerial Task Force on Affordable Housing in New South Wales, Affordable Housing in NSW: the Need for Action, New South Wales Government, Sydney, 1998

[12] Michael Darcy, 'Housing: the Great Divide' in John Connell, (ed), Sydney: the Emergence of a World City, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2000; Michael Darcy, 'Pathways to Homelessness: Assessing the impact of structural and socio-demographic factors on the scope and nature of homelessness in Sydney', National Housing Conference, Brisbane, October 2001

[13] Frank Stilwell, Globalisation and Cities: An Australian Political Economy Perspective, Australian National University Urban Research Program, Canberra, 1997

.