The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Harriet and Helena Scott

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Harriet and Helena Scott

[media]Harriet and [media]Helena Scott were the foremost natural science painters in New South Wales from 1850 until turn of the century, despite being born in an age when female scientific education was limited, women's 'gifts' were to be kept in the private sphere of home and hearth, and the professions were a male preserve. In Australia, as in England, the study of natural history was the pursuit of gentlemen, for whom amassing a collection was a status symbol. Yet, through prodigious talent, Harriet Scott and her younger sister Helena became esteemed as professional artists, brilliant natural history illustrators and meticulous specimen collectors. Contemporaries hailed their contribution to late colonial natural science, yet they were mostly forgotten until the twenty-first century.

Background

The Scott sisters were daughters of Harriet Calcott, who was born in New South Wales in 1804 to a free woman, Catherine White, and the emancipist and 'convict made good' Richard Calcott. Calcott worked for the prominent Sydney merchant and pioneer Robert Campbell and by the 1820s owned a number of properties in the Rocks.

Harriet Calcott had two daughters, out of wedlock, by the time she was 19. Despite the outward rules of moral propriety, whereby an unmarried woman who gave birth was 'outcast' from society, the social mores in colonial Australia were somewhat more accommodating. When the brilliant, intrepid and very respectable Alexander Walker Scott arrived in New South Wales in 1829 he was little concerned that Harriet had 'a past' and accepted her two daughters into his household. Although Harriet Scott was born in 1830 and her younger sister Helena followed in 1832, Alexander and Harriet only married in 1846, when the girls were teenagers. [1]

[media]Walker Scott, a free settler, received a considerable grant of land shortly after arriving. As well as being a grazier and entrepreneur, he was an entomologist and a trained artist with a lifetime interest in natural science. He inherited his passionate curiosity for botany and entomology from his father, Dr Helenus Scott, a physician and botanist who worked for the East India Company in India for thirty years. This familial legacy shaped the trajectory of the Scott sisters' personal and professional lives. [2]

Ash Island

The girls were schooled and educated by their father, firstly in Sydney and then at his estate on Ash Island in the Hunter River of New South Wales, where the family went to live in 1846. Ash Island, 2560 acres (1,000 hectares), had been granted to Alexander Walker Scott in 1829. It was a 'naturalist's paradise' with a visually splendid and luscious landscape of red cedar, coastal ash trees, mangrove and swamp oak and many species of eucalypt. The natural scientist and explorer Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt visited the island and the Scott estate in 1842. In a letter to his friend Lieutenant Robert Lynd he wrote

…it is a remarkably fine place, not only to enjoy the beauty of nature, a broad shining river, a luxuriant vegetation, a tasteful comfortable cottage with a plantation of orange trees, but to collect a great number of plants which I had never seen before…Climbing Polypodium, the Aerostichum growing on the trees, a great number of creepers, the nettle Tree, the Caper, the native Olive and many others. [3]

[media]Here the Scott sisters began their life-long love affair with nature and botany, putting nature on paper, engraving it in stone and collecting hundreds of specimens. Marion Ord has written that, in this environment, they were

…able to master, under their father's eye, the intricate, exact techniques of painting and the knowledge of botany and entomology necessary to natural science illustrators. [4]

The girls' mother also encouraged their interest in the natural world. As Helena recalled in a letter written to her friend Edward Pierson Ramsay in October 1862

How beautiful the native flowers are at this season! Our railway line is positively resplendent with the yellow dogwood, blue campanula and scarlet bottlebrush. Somehow the scent of native flowers is always associated in my mind with the days when we were tiny little children and Mamma used to take us in the early morning for long rambles in the fragrant brush (then) around the Botanical Gardens. It is wonderful how these early recollections, associated with the sight or scent of peculiar flowers, cling to us… [5]

Between 1852 and 1883 the sisters painted over 160 plant species from the countryside between Ash Island, Newcastle and the Illawarra. They also collected around Port Jackson, Manly, Lane Cove, Burwood, the Blue Mountains and Springwood, creating a catalogued treasury of the natural botanical life of New South Wales. Harriet or 'Hattie' as she signed herself, and her sister 'Nellie', became well known among members of the Entomological Society, of which their father was a founding member, earning high praise for their detailed, intricate paintings of Australian insects and native flowers. The sisters corresponded with colonial and international scientists and executed commissions for them.

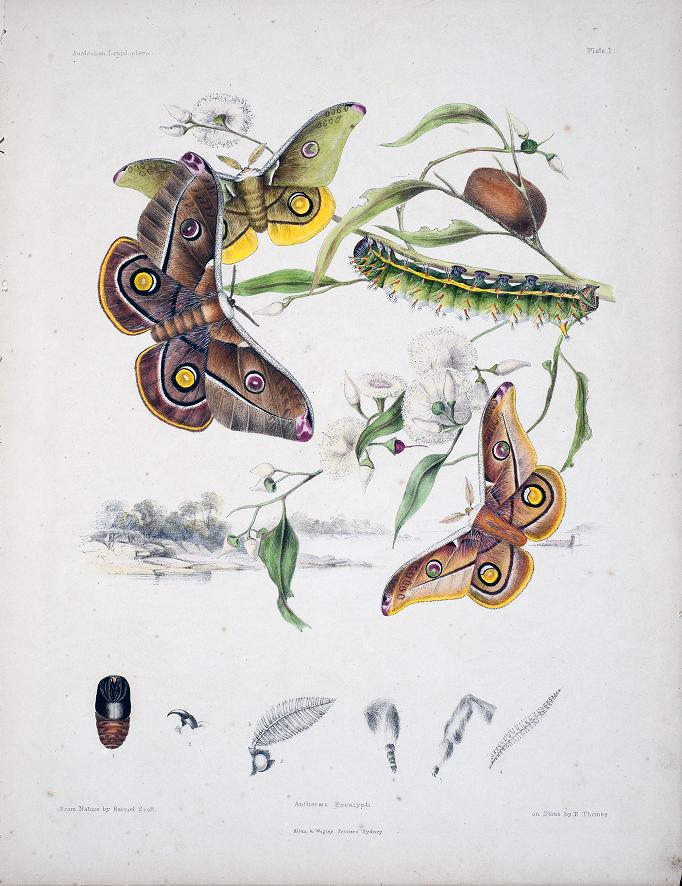

Australian Lepidoptera and their Transformations

[media]The Scott Sisters were elected honorary members of the Entomological Society after the publication of their most famous work, Australian Lepidoptera and their Transformations. The text was written by their father, whilst Harriet painted most of the moths and Helena the butterflies. [6] Although the work was not published in London until 1864, it was completed in 1851 when the sisters were only 21 and 19 years of age. An early and very favourable review of the book, by the eminent botanist, naturalist and zoologist William Swainson, appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald in August 1851. [7] Swainson welcomed 'the accuracy of observation' and the exact precision of Scott's writing 'which certain entomologists who have recently published…in England would do well to imitate'. Swainson's most ebullient praise was, however, reserved for Harriet and Helena's illustrations.

Of the execution of these drawings I am almost afraid to write lest the public may think that the desire of complimenting the fair artists may have biased my judgement. I am willing, however, to hazard that scrupulous regard for veracity which the scientific public has long given me credit for, when I state that these drawings are equal to any I have ever seen by modern artists…whether, in short, we look to the exquisite and elaborate finishing, the correct drawing, or the astonishing exactitude of the colours, often most brilliant and generally indescribably blended, there is no poetic exaggeration in saying: The force of painting can no further go…every tuft of hair in the caterpillar, the silken web of the cocoon, or the delicate and often intricate pencillings on the wings of a moth, stand out with a prominence of relief which is perfectly impossible to reproduce by simple watercolours. [8]

The Lepidoptera Paintings

The sisters were equally talented and it is difficult to tell Harriet's work from Helena's without checking for their signatures. Their manner of working together made the Lepidoptera paintings both remarkable and exceptional, for they combined accurate scientific detail with stunning visual appeal. Their illustrations were completed with the aid of microscopes to capture the exact colour, texture and details of tiny body parts. They depicted the life cycle and host plants of each species and often included background landscapes, such as familiar locations in and around Sydney, which revealed further information about the habitat of the insects. These landscapes were executed in black pen and ink wash or light colours, to contrast with the vibrant colours of the insects. This contrasting technique was unique to the Scott sisters – few contemporary natural history illustrators at the time used such backgrounds in their work. Harriet and Helena often worked with living specimens whilst most natural history illustrators used long-dead, pinned specimens that faded and shrank, losing the kaleidoscopic colour of their living counterparts. [9] The Lepidoptera paintings, as a result, are known for their lifelike poses and vibrancy.

Growing recognition

Swainson's review was the first public recognition of the extraordinary talents of the Scott sisters and it was not to be the last. During the 1850s and 1860s the sisters were engaged and absorbed in their art, receiving praise and support from family friends, overseas visitors and increasingly from the wider society. They worked mainly in watercolour and pen and ink but also produced pencil sketches and lithographs. In 1860, Helena's intricate painting of Christmas Bush Ceratopetalum gummiferum was reproduced as plate vii in George Bennett's Gatherings of a Naturalist in Australasia. [10] Helena's paintings of native wildflowers and plants are among her finest and most enticing works – [media]her 1854 Butterflies with Passionfruit Flower is a prime example. [11] The English artist and traveller Marianne North bought some of Helena's works when she visited Sydney in 1889. [12]

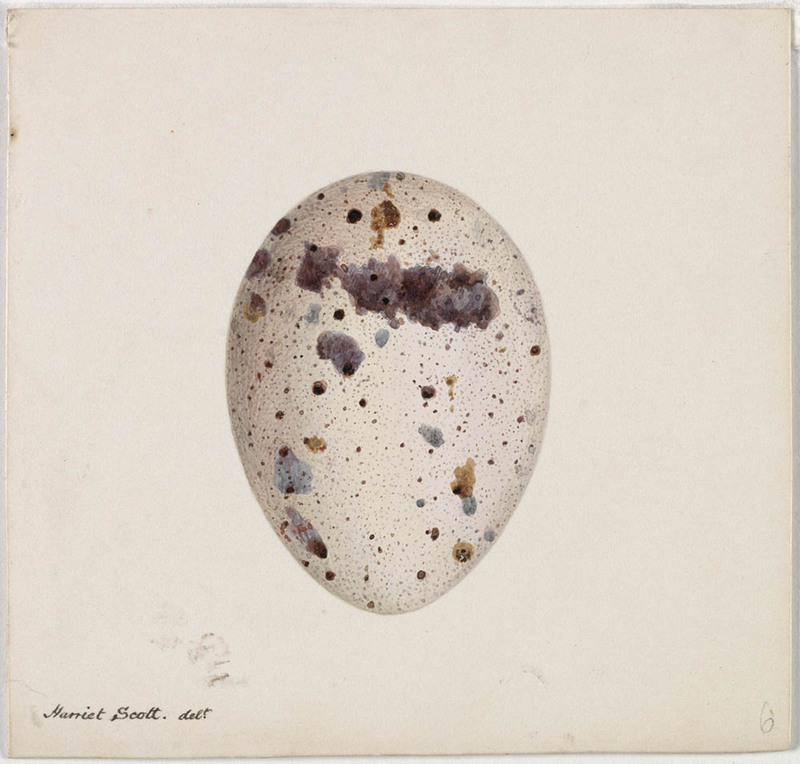

[media]The Scotts were part of an influential extended family that mixed with scientists, explorers and experts. Their cousins included Rose Scott, the feminist and social reformer and David Scott Mitchell, whose extensive book collection (which included the Scott sisters' work) was bequeathed to the state to form the Mitchell Library. Of particular significance was their relationship with the Ramsay family, including a long lasting friendship with Edward Ramsay, who would become the first Australian born Curator (or Director) of the Australian Museum in Sydney, and whose surviving letters and papers reveal much about the sisters' lives. [13] Harriet and Helena wrote candid, lively and intelligent letters to Ramsay that express both joyfulness in progress and frustrations with their scientific and artistic endeavours. In one such letter, from Ash Island in October 1862, Helena acknowledged the utmost gratitude she felt towards her father for the unusual 'freedoms' he permitted his daughters

Oh! You cannot think how thankful I am that my dear father allows me to place my name to the drawings! It makes me feel twice as much pleasure while painting them. [14]

Despite their privileged family, education and talents, the sisters still felt the social and cultural constraints of nineteenth century femininity. In 1865, at the age of 35, Hattie wrote of her

…great desire to distinguish myself in some way or other, and if I were only a man I might do it, but as I am a woman I can't try, for I hold it wrong for women to hunt after notoriety. [15]

Yet the woman who admitted that she wished that she should have been 'Harry' Scott instead of 'Hattie' Scott and had the opportunity of the university education enjoyed by her cousin David and her friend Edward, was obviously proud of her work. In a letter to Ramsay confided 'Fancy Mr [Johan] Krefft introducing Papa to a friend of his…a Mr Pitt…and the said Mr Pitt accosting Papa with "Are you the Mr Scott that has the clever daughters?"' [16]

Harriet in Wollongong

During the 1860s Harriet spent some time with friends in Wollongong and painted many scenes from 'this lovely district' including Berkeley Avenue, Wollongong (1861, oil), two other oils, several watercolours and some work in sepia. [17] Her delight in the natural landscape was encapsulated in a letter written in 1865 describing the Bong Bong Mountains where she saw

…some of the grandest valleys…one where the huge Fig trees looked just like rose bushes and Cabbage and Bangalow Palms as if they were green mops of six feet high! There seems such a variety of trees and plants in these valleys, I wonder if they are all known? [18]

Her return to Ash Island that year was accompanied with a sense of frustration at the daily duties demanded of an unmarried, dependent daughter. As she wrote to Ramsay in October 1865

I have had such a lot to do about the house since I came back that I have not been able to gaze at my stamp book and play on the piano yet. I wish houses and servants did not exist, or that breakfasts, dinners and teas were never required, and then I could have a lot of time to enjoy myself. [19]

Helena's marriage to Edward Forde

Helena – Nellie – also inherited the family passion for discovery and adventure, and may have been even more adventurous than her elder sister. She was a keen eyed naturalist, lithographer, an engaging letter-writer and an intrepid explorer in the service of science. In 1864 she married the Anglo-Irish artist and navigator Dr Edward Forde. [20] Her younger cousin Rose Scott, who she was close to, attended the wedding on Ash Island. [21] Forde was described by a contemporary as 'a gentleman no less admired for his amiable disposition than distinguished for his scientific attainments.' [22] He was the chief draughtsman in the Department of Harbours and River Navigation.

In 1865 the intrepid newly-weds travelled to Adelaide and then up the Darling River where Forde had been commissioned to survey the area for obstructions to river navigation. The journey, only five years after Burke and Wills' tragic expedition, involved traversing a hostile and rough environment, but Helena seems to have felt no particular hardship and revelled in the scientific and artistic opportunities of the expedition. During her time on the Darling she drew a series of sketches portraying camp life and the country through which they were passing.[23] Helena collected and painted many botanical specimens around the campsites and proposed to use them in a forthcoming book, Flora of the Darling. However tragedy struck near Menindee where they both contracted typhoid fever. While Nellie recovered, Edward died on 20 June 1866 'of low fever and exhaustion'. [24]

The loss of Mrs Scott and Ash Island

The year 1866 was particularly sad for the Scott family. The sisters lost their beloved mother Harriet in January 1866, and further distress and anxiety ensued later in the year when Alexander Walker Scott was declared bankrupt. The Scott's much-loved Ash Island was sold and Harriet, together with her father and half-sister Mary Ann Calcott, moved back to Sydney. Despite the loss of her mother and the wrench away from their idyllic home on Ash Island, which had shaped and influenced her talents and passions, Harriet cheerfully and stoically tried to embrace the life of the city 'where we can be much happier than at so very quiet a place'. [25] From 1867 the sisters lived with their father at Craig-end Terrace, Darlinghurst, once owned by Sir Thomas Mitchell. They later moved to Ferndale, near to Rushcutters Bay. This property, like the Ash Island estate before it, became famous for its beautiful and luscious gardens.

Walker Scott was appointed a Land Titles Commissioner in Sydney and the sisters worked to support the family. Helena returned to Sydney and eked out a living from painting on commission. She gave her material from her travels in the Darling region to the clergyman-botanist William Woolls for his A Contribution to the Flora of Australia (1867). Woolls was ever grateful and in his book acknowledged 'the fortitude with which Mrs Forde encountered the difficulties of the expedition, and the melancholy circumstances which deprived the colony of an able and efficient officer', saying he believed such tragic circumstances 'attach peculiar interest to the collection.' [26] Woolls stated that Helena's specimens and sketches were probably 'the most representative collection of plants from the lower Darling River actually brought to Sydney up to this time', as earlier specimen collections had gone to Melbourne.' [27] Helena and Woolls would remain friends and scientific colleagues for many years following this generous gift of her specimens and her art.

Shells, reptiles, mammals and Christmas cards

For several years Harriet and Helena executed almost all the artwork for the scientific literature produced in Sydney. This included James Charles Cox's Monograph of Australian Land Shells (1868) and Johann Ludwig Gerard Louis Krefft's The Snakes of Australia (1869) and The Mammals of Australia [media](1871). [28] [media]In the preface to his 1869 collection Krefft thanked the sisters for their excellent and accurate illustrations

The gifted daughters of AW Scott, Esq, MA – Miss Scott and Mrs Edward Forde – have done everything in their power to give correct figures of the reptiles illustrated. This task (one of peculiar difficulty, as every naturalist knows) has been well carried out, and the different species will be easily recognised. [29]

The plates which they illustrated for Krefft's 1871 collection were exhibited by him under his own name in the 1870 Sydney Intercolonial Exhibition, but the juror's report noted that the works were 'principally lithographs of snakes and native animals, which were drawn on stone by Mrs Forde and Miss Harriet Scott, and are deserving of very high commendation'. The judges added 'these remarks equally apply to the lithographs printed and exhibited by the Government Printer, of native animals – drawn by the same ladies for the Council of Education'. [30]

Later, in 1879 and 1880 Helena and Harriet drew the designs for some of the first commercial Australian Christmas cards using native flowers. These cards were produced as a set of twelve in postcard format and printed by Turner and Henderson in Sydney. [31]

Harriet's marriage to Cosby Morgan

In 1882, at the age of 52, Harriet married a long-term friend, the recently widowed Dr Cosby William Morgan. Becoming a doctor's wife and inheriting four teenage daughters (who it seems, resented her) meant she had little leisure to paint and the volume of her work considerably diminished. Although their acquaintance and friendship had been a long one, historians have suggested that the marriage was not a particularly happy one. [32] Despite this, the couple lived for many years at Pambula on the south coast of New South Wales. Harriet painted several landscapes of the countryside between Newcastle and the Illawarra and south-coast regions and one of her last known commissions was for the 1879, 1884 and 1886 editions of The Railway Guide of New South Wales. For this she drew the many delicate ferns and native flowers that dotted the landscapes and railway lines of the Blue Mountains area. [33]

Walker Scott's death

Alexander Walker Scott died at Paddington in 1883 and was buried in Waverley cemetery. Sometime after her father's death, Nellie moved to Roslyn Gardens in Darlinghurst (now part of Kings Cross.) Despite her success and prestigious contacts, her financial position, as a freelance artist and collector and a single woman with little property, was always precarious. [34] She persuaded the Australian Museum to publish the second volume of the Lepidoptera in five parts between 1890 and 1898. Later in 1904 at the age of 72 Helena was boarding with a 'quiet couple' in Harris Street, Harris Park. She wrote to her cousin George in Newcastle that she had applied to the museum for some scientific work connected with her father's Australian Lepidoptera 'as I must try and earn a little money somehow to keep the wolf from the door and I hope I shall get it – as it is the only work I am fit for.' [35]

The deaths of Harriet Scott and Helena Forde

Harriet died at Granville, Sydney on 16 August, 1907, aged seventy-five. She had lived all her life in New South Wales. The flowers, the landscapes and the wildlife that she encountered here, had deeply informed her life and her work. Today her paintings bear testimony to her enormous gift and talents, but also to her great love of natural history, of botany and ultimately, of New South Wales. Three years later, Helena died at Harris Park on 24 November 1910, aged seventy-eight. An obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald hailed her as 'the last of the artist naturalists' and noted that she had been 'a warm hearted, cultured woman of very considerable intellectual gifts'. [36] JJ Fletcher of the Linnean Society reflected on the contribution both women had made to the science and art of New South Wales and said he regarded Helena's death as marking the passing of an era of outstanding scientific and artistic achievement – 'to these artist-naturalists we owe most of the figures in the scientific literature of the period produced in Sydney.' [37]

Sydney and the legacy of the Scott family

Harriet, Helena, Rose and David Scott Mitchell – none left descendants, but all left an enduring cultural, social and artistic legacy to Sydney, to New South Wales and indeed to Australia. Rose is remembered for her feminism, her liberal thought and her social reform activism and David left the magnificent Mitchell Library. Harriet and Helena, through their scientific and artistic talents and accomplishments, created an extraordinary and beautiful collection of nineteenth century Australian art. In 1851 William Swainson had concluded his review of the Lepidoptera with the following observation:

I cannot but hope that the Australian public…will reap honour to themselves by patronising what is to them a NATIONAL WORK, and thus not only confer a great and lasting benefit to science, but manifest…that we have both native talent and the wealth and disposition to foster and uphold it. [38]

The Scott sisters were forgotten for a long time but careful preservation of the tangible remnants they left behind – their letters, plates, albums, specimens and sketch books at the Australian Museum and at the Mitchell Library – have enabled their work to survive. Their art continues to inform and delight today. [39]

Further reading

Joan Kerr, ed. The Dictionary of Australian Artists; Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992

Marion Ord, ed. Historical Drawings of Native Flowers: Harriet and Helena Scott. Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988

Ronald Strahan et al. Rare and Curious Specimens; An Illustrated History of the Australian Museum, 1827-1979. Sydney: The Australian Museum, 1979

Notes

[1] Richard Calcott had been transported to New South Wales in 1799 on the Hillsborough after being convicted for theft. Harriett's daughter Mary Ann was born in 1820 when Harriet was just 15 years of age. Mary Ann's father, Ensign Edward King of the 48th Regiment was recalled back to England 'on family business' before she was born. Harriet's second daughter, born in 1823, was Frances (Fanny) Murdoch Stirling, child of Lieutenant Robert Stirling, aide-de-camp to Governor Brisbane. Stirling lost his life at sea in 1829, supposedly at the hands of pirates, somewhere between India and England. Mary Ann remained unmarried and lived at home with the Scotts until her death in 1889. Fanny went on to marry William Charles Ludwig Kirchner, who was German immigration officer at Grafton and brought the first German immigrants to New South Wales. Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Native Flowers, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 18.

[2] Walker Scott was born on the island of Salsette near Bombay. The Scott family left India in 1809 and returned to England where Scott and his four brothers were educated. Their father Helenus encouraged his sons to look to the colonies to make their mark on the world

[3] Marcel Aurousseau, editor and translator, The Letters of FW Ludwig Leichhardt, Volume 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968): 526

[4] Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Moths and Butterflies, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 15

[5] Mitchell Library, Letter from Helena Scott to Edward Pierson Ramsay, 22 October 1862. Correspondence and miscellaneous papers 1860-1912 (Ramsay), Mitchell Library MSS 563. Edward Pierson Ramsay (1842-1916), ornithologist and zoologist, would become the first Australian-born curator of the Australian Museum in 1874, remaining in this role until 1894. He was the founding treasurer of the Entomological Society of New South Wales and was involved in the establishment of the Linnean Society of New South Wales in 1874, which aimed 'to promote the cultivation and study of the science of natural history in all its branches.' Its first President was Sir William Macleay (1820-91) who was one of Helena Scott's art patrons

[6] The full title was Australian Lepidoptera and their Transformations, drawn from the Life, by Harriet and Helena Scott: with Descriptions, General and Systematic by AW Scott, MA. The original plates for this publication are in the Australian Museum, Sydney

[7] 'SWAINSON, William, 1789–1855', An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by AH McLintock, An Encyclopedia of New Zealand 1866, http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/swainson-william-1809-1884, viewed 26 February 2015

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 30 August, 1851: 2

[9] Fran Dorey, A biography of the Scott sisters, http://australianmuseum.net.au/A-biography-of-the-Scott-sisters, viewed 26 February 2015

[10] George Bennett, Gatherings of a Naturalist in Australasia: Being Observations Principally on the Animal and Vegetable Productions of New South Wales, New Zealand, and some of the Austral Islands (London: John Van Voorst, 1860)

[11] [Butterflies with passionfruit flower], 1854 / Helena Scott, State Library of New South Wales, DL pd 779, a128970, http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_DAMl/image/21/144/a128970r.jpg, viewed 26 February 2015

[12] Marion Ord, 'Scott, Helena' in Joan Kerr, ed, The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 707

[13] A proposed work between Ramsay and the Scotts, On the Oology of Australia, got the sisters busy collecting and painting birds' eggs and nests in the early 1860s. Harriet Scott and Helena Forde, Drawings of bird's eggs to illustrate a proposed work on oology by E P Ramsay with other natural history drawings by Helena Scott and Harriet Scott, ca 1861. State Library of New South Wales, PXA21, http://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=430795, viewed 26 February 2015

[14] Letter from Helena Scott to Edward Ramsay, 22 October 1862, Correspondence and miscellaneous papers, 1860-1912, Mitchell Library MSS 563

[15] Letter from Hattie Scott to Edward Ramsay, 19 November 1865, Correspondence and miscellaneous papers, 1860-1912, Mitchell Library MSS 563

[16] Johann Ludwig Gerard (Louis) Krefft was the curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney from 1861 until his dismissal in 1874. He was also a scientist, author, prolific sketcher and naturalist. There was a fierce personal and professional rivalry between him and Edward Ramsay, who succeeded him at the Australian Museum in 1874. Letter from Hattie Scott to Edward Ramsay, 31 December 1865, Correspondence and miscellaneous papers, 1860-1912, Mitchell Library MSS 563

[17] Marion Ord, 'Scott, Harriet' in Joan Kerr (ed) The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 707

[18] Quoted in Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Native Flowers, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 25

[19] Letter from Hattie Scott to Edward Ramsay, 27 October 1865, Mitchell Library MSS 563

[20] After her marriage she signed her work 'Helena Forde', sometimes just '4D'

[21] Judith A Allen, Rose Scott: Vision and Revision in Feminism (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1994): 37

[22] William Woolls, A Contribution to the Flora of Australia (Sydney: F White, 1867): 192

[23] . Darling River Series by Helena Forde (Scott) 1865-66, Mitchell Library 2PX A551

[24] Marion Ord, 'Scott, Helena' in Joan Kerr, ed, The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 707

[25] Quoted in Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Moths and Butterflies, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 29

[26] William Woolls, A Contribution to the Flora of Australia (Sydney: F White, 1867): 193

[27] Dr Lionel Gilbert, Armidale, NSW, quoted in Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Native Flowers, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 29

[28] In the Preface James Cox wrote, 'The Illustrations, kindly executed for me by Miss Scott and Mrs Edward Forde, speak for themselves, and I have no doubt will be duly appreciated by the public'. Interestingly the copy held at the Mitchell library once belong to Cox's contemporary Gerard Krefft. See JC Cox, A Monograph of Australian Land Shells (Sydney: William Maddock, 1868)

[29] G Krefft, The Snakes of Australia: Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue of all the Known Species (Sydney: Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1869). In the copy held in the Mitchell Library, there is a delightful handwritten letter enclosed in the front cover of this book, written to Helena from Krefft. It is dated March 7 1863 and is a thank you letter for her recent donations of frog, lizard, bat and snake specimens to the Australian Museum. Krefft also wrote that any further specimens in the future 'especially small mammals' would be gladly received. Finding this unexpected letter was a moment of absolute and utter historical magic for the author

[30] Quoted in Marion Ord, 'Scott, Helena' in Joan Kerr, ed, The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 707

[31] See plates 37 and 50 in Marion Ord, ed, Historical Drawings of Native Flowers, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 108-09, 134

[32] Judith Allen suggests that it quickly ended in separation however Marion Ord and others merely hint that it was 'unhappy'. My own research reveals Helena mentioned going to stay with her sister and 'the Doctor' for 13 months in a 1904 letter to her cousin George, so even if it was an unhappy alliance, it was an enduring one. Judith A Allen, Rose Scott: Vision and Revision in Feminism, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 38: Marion Ord, Historical Drawings of Moths and Butterflies, Harriet and Helena Scott (Roseville: Craftsman House, 1988): 30

[33] New South Wales Government Railways and Trams, The Railway Guide of New South Wales. (For the use of Tourists, Excursionists, and Others). A Convenient Volume of Reference to Railway Routes, Stations and Places of Interest on the Lines of Railway: Containing a Map of the Blue Mountains and Numerous Illustrations (Sydney: Government Printer, 1884)

[34] Helena's patrons included WJ Macleay, Thomas S Mort, Baron von Mueller, Sir George Macleay and Sir William Macarthur. Despite these wealthy patrons, Helena's financial difficulties worsened after the death of her father in 1883. In 1884 Helena sold a bundle of Walker Scott's papers to the Australian Museum, including notes, drawings and a handwritten manuscript of the Lepidoptera. She later sold field notebooks, drawings, correspondence, dried botanical specimens and beautiful water colour plates of moths and butterflies that the sisters had made in the 1850s and 1860s for their father's landmark publication. The Museum's entomology department also holds a collection of insects collected by the Scott family in the course of their lepidoptera research, also sold by Helena Scott in 1884.

[35] Quoted in Marion Ord, 'Scott, Helena' in Joan Kerr, ed, The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 707

[36] Sydney Morning Herald, 'The Last of the Artist Naturalists', Wednesday 14 December 1910: 5

[37] Quoted in Marion Ord, 'Scott, Helena' in Joan Kerr, ed, The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870 (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1992): 708

[38] Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 30 August 1851: 2

[39] In 2011 the Australian Museum held an exhibition Beauty from Nature: Art of the Scott Sisters, a testament to the enduring beauty and astounding accuracy of their scientific and artistic work This has since become a touring exhibition. Australian Museum, 'The Scott Sisters', http://australianmuseum.net.au/Beauty-from-Nature-art-of-the-Scott-Sisters, viewed 26 February 2015

.