The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Glebe

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Glebe

Aboriginal clans [media]of the Sydney region observed the First Fleet enter Port Jackson in January 1788. The pale-skinned people ( gubbas) the ships brought from Britain would quickly have a catastrophic impact on their lives. The territory of the Cadigal and Wangal clans adjacent to the British settlement at Sydney Cove embraced a tract measured out in 1790 as the Sydney Glebe lands. Smallpox (galgal) swept through the local Indigenous population within 18 months of first contact, killing half the Aboriginal population of the Sydney district. [1]

Church lands

Governor Phillip's instructions from the British authorities directed him to allocate 400 acres (161.8 hectares) in each township to support a Church of England clergyman. [2] The first chaplain appointed to the colony, Richard Johnson, set out to clear his heavily timbered glebe, which he later wrote was unsuitable for cultivation; it was '400 acres for which I would not give 400 pence'. About 1794, Johnson obtained a much more productive 100-acre (40.4-hectare) grant which he named Canterbury Vale, where he engaged in stock raising and agriculture, ending his contact with Glebe. [3]

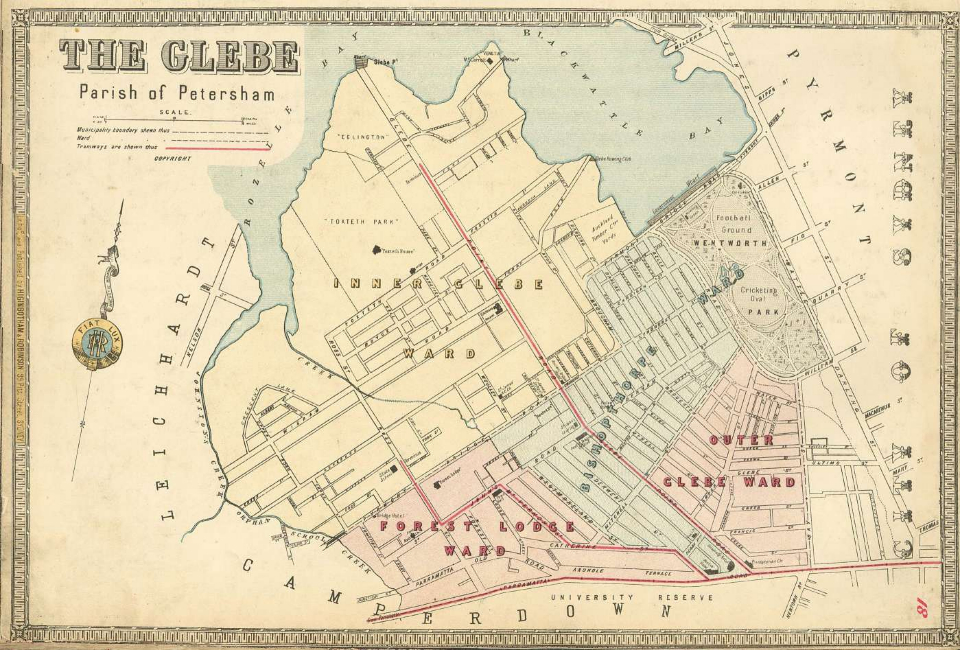

The Hawkesbury [media]sandstone ridge runs from south-east to north-west through Glebe. The soft Wianamatta shale capping the sandstone has weathered to produce gently rolling summits with contours ranging from 20 to 30 metres, and its original vegetation was influenced by shale-derived soils. [4] On Glebe's eastern, northern and western limits, where the underlying Hawkesbury sandstone outcrops, steep cliff faces appear. The ridges were drained by Blackwattle and Johnstons creeks, carving shallow valleys into the physical landscape.

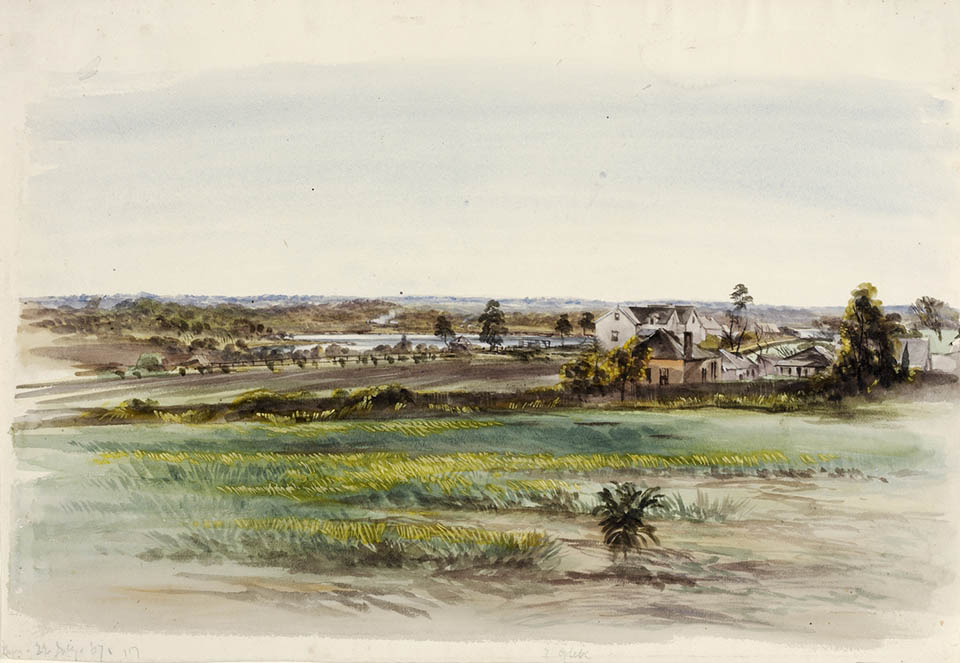

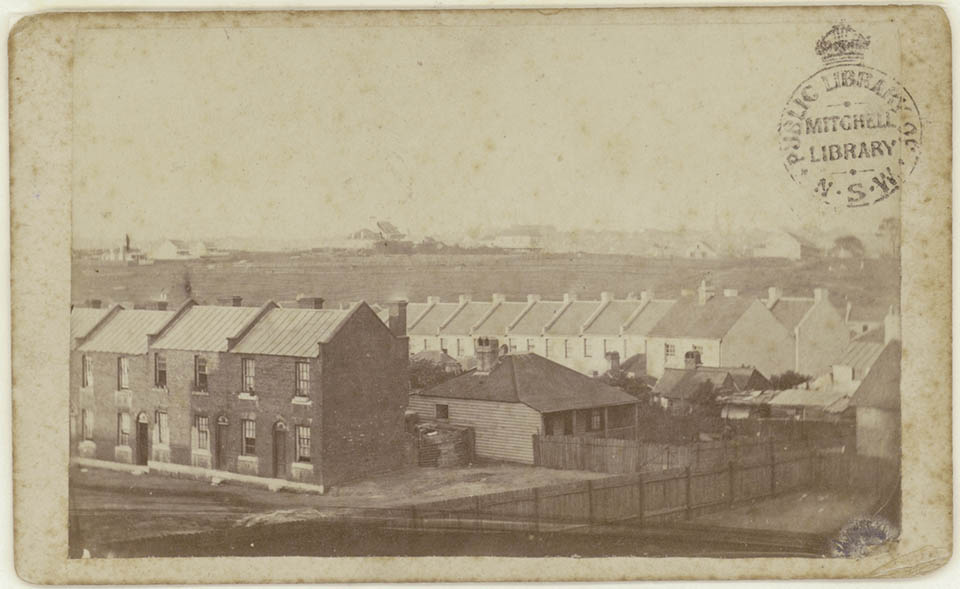

Small portions of Glebe were leased for cultivation of cereal crops and vegetables, but most of the church reserve remained unoccupied until the Church and School Corporation, 'in view of the pressing needs of clergy', subdivided Glebe into 27 allotments and auctioned most of it in 1828. [5] The first to flee the befouled town of Sydney in the late 1820s, and create 'clusters of elegant dwellings and pleasure grounds' on the urban perimeter, were families of professional and mercantile men, and the administrative elite who sought to fulfil dreams of self-importance and respectability. [6]

The larger, more elevated allotments at Glebe Point appealed to middle-class bidders with a clear preference for better drained sites with a view. At Glebe's other extremity, smaller, low-lying lots near Blackwattle Swamp, close to a freshwater creek, attracted commercial activities, slaughterhouses and boiling-down works, and a distillery nearby. Residential dwellings erected in the vicinity were of the cheapest type. [7] Topography was an important social and sanitary consideration in early suburban development, and the original subdivision boundaries, staked out in 1828, acted as a framework which rigidly dictated the layout of Glebe's streets. [8]

Elegant dwellings and pleasure grounds

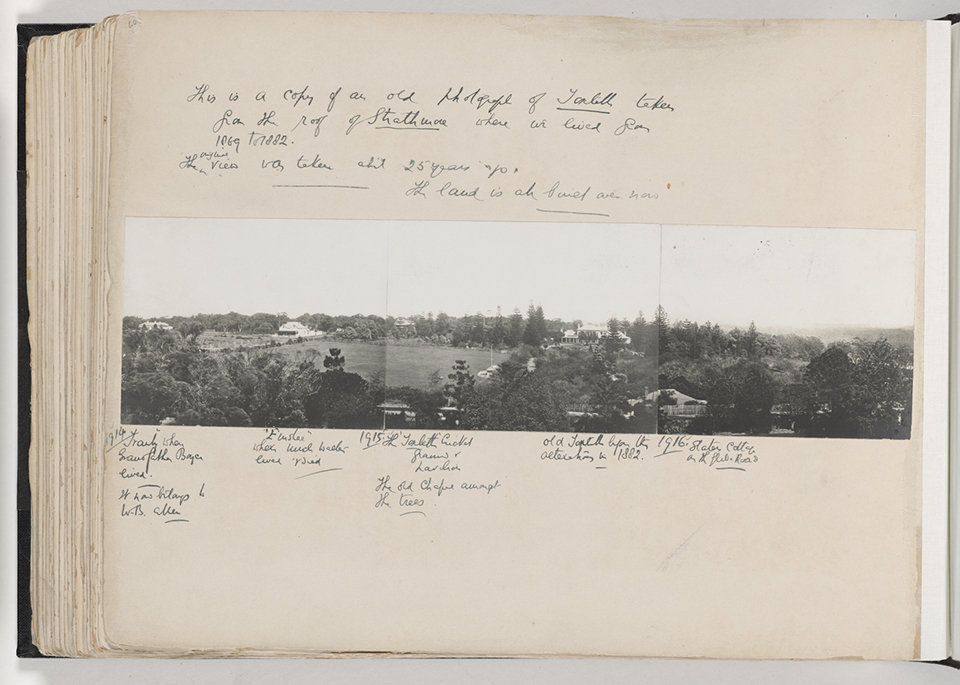

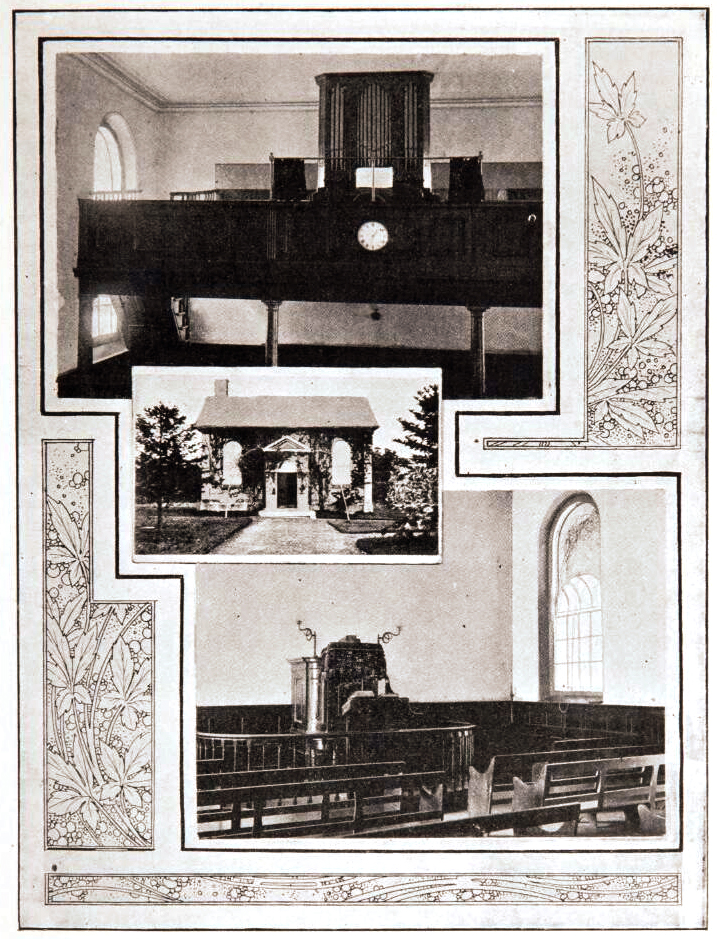

The [media]largest Glebe Point landowner was George Allen, who in 1831 moved to his John Verge-designed Toxteth House which embodied the essence of respectability, wealth and physical comfort, dominating his 95-acre (38.4-hectare) estate with its 'spacious garden containing several hundreds of fruit trees' and 15 convict servants. Later the landed lawyer added a [media]private Wesleyan chapel and turf cricket ground. [9]

Several of the 13 owners of Glebe's semi-rural retreats in 1841 were merchants and traders who grew wealthy on the Pacific trade or an annually increasing wool clip, and picturesque architectural styles designed for a middle-class dreaming of landed possessions and status became a feature of the Glebe landscape. The size of their mansions and spacious grounds, and the numbers of domestic servants they employed, demonstrated the wealth and social standing of the occupants. Villa building in Glebe was largely confined to two broad territories. One group was consciously aligned along and close to the ridge that Glebe Road followed from St John's Road to the water, and the other cluster was on either side of Bridge Road between Glebe Road and Ross Street. [10]

'So [media]rapidly has population spread and multiplied in the suburbs', wrote Ralph Mansfield in 1846, 'that its aggregate numbers are now but little short of one fifth of the population of the city'. [11] Mansfield accorded the title of suburb for the first time to these areas encircling the city. On exploratory walks around Sydney in 1858, William Jevons discerned three broad social areas in Glebe. The first-class residences, he recorded in his notebook, were concentrated on elevated land, where, beyond Bridge Road, the main artery Glebe Road 'entered the rural first class suburb of Glebe Point'. At the other extremity, third-class residences, he wrote, occupied the lowest and least desirable localities. He described the precinct around Blackwattle Creek as 'unhealthy and disgusting'. [12] Jevons's sharp focus on social topography, revealing a clear pattern of class segregation in Glebe, was reinforced by data in the 1861 census. [13]

Terracing Glebe

The process of [media]building up Glebe and peopling its streets spanned the years between 1841 and 1915, with the most intensive phase occurring in the 20 years after 1871. Those parts of Glebe closest to the main routes into the city, especially Parramatta Road, were the first to experience intensive residential development. Accommodation within easy walking distance of city work places, or public transport links to them, was of fundamental importance to potential residents and developers of the suburb. [14]

The terrace became the [media]dominant built form in Glebe from about 1870, providing sufficient resources to accommodate rapidly growing population in self-contained private housing space for an economy of outlay on land and building materials. [15] Significant economies could also be derived from regular and continuous development and, multiplied over tracts of the townscape, the terrace produced a distinctive texture of relief. The straight lines of the post-Regency terrace gave way to the Italianate style of the 1880s where at least four types of this terrace were discernible. By 1915 Glebe's diversity of domestic architecture – colonial Georgian, Regency, Victorian Gothic, Italianate and Federation styles – broadly corresponded with the periods in which the suburb was built up. [16]

Throughout the nineteenth century, Glebe was a well [media]defined social mosaic of middle-class, lower middle-class and working-class neighbourhoods, sharply divided along class lines. It was a highly stratified and unequal society with the occupants of Italianate cottages and terraces at Glebe Point as the social leaders of the community, enjoying near-absolute sway through the whole range of suburban institutional life. Glebe's parliamentary representatives, Protestant urban men of independent means, came out of the same mould as Glebe's councillors, self-made men who fervently supported free enterprise and opposed trade unionism. [17] However, as the century drew to a close, the social boundaries that characterised the neighbourhoods of Glebe were about to become much hazier.

Working-class Glebe

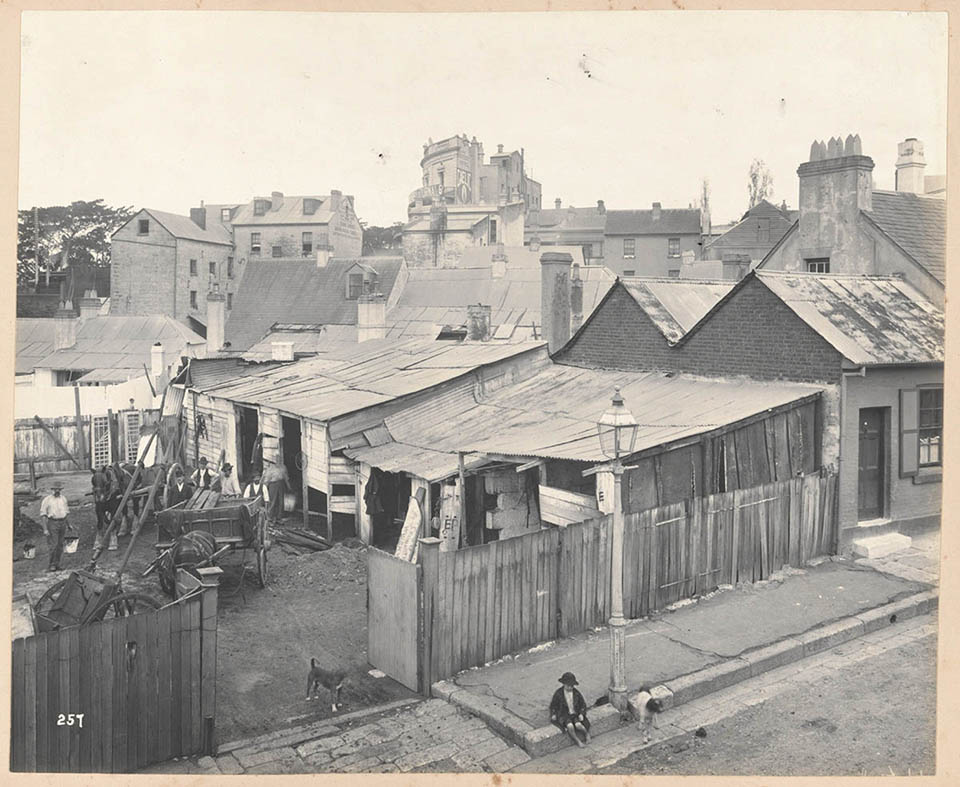

Glebe's [media]open spaces were rapidly being filled with new people, new houses and industry, accommodating 19,220 people in 3,737 houses by 1901. [18] A growing middle-class perception of inner Sydney as a breeding ground for disease, poverty and vice was reinforced by the outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900. The movement of the better-off, with their rising incomes to semi-detached houses and bungalows with gardens in the new suburbs just beyond the main centres of population, took place like a series of rings on the townscape, accompanied by a gradual but perceptible change of class in the inner ring. The places they left behind were increasingly taken by people on lower incomes, especially blue-collar workers who had to remain close to the city where they could pick up a few days' work. In the first decade of the new nation, a zone embracing Redfern, Newtown, Surry Hills, Camperdown, Paddington, Glebe and Balmain became more industrialised and overtly working-class in their demographic profile, and were transformed into blue-ribbon Labor Party electorates. [19] And in contrast to those ensconced in Glebe Town Hall before 1925, the new councillors were Labor, predominantly Catholic, and wage earners. It was a social pattern that would not be drastically revised for a long time. [20]

To the casual observer, Glebe is a seemingly shapeless tract of suburban Sydney with no decipherable pattern. A triangular piece of land covering 240 hectares about two kilometres west of Sydney's central business district, Glebe is in many ways typical of inner-city suburbs in Western societies and, in common with other areas close to the city, it has narrow streets, back lanes, a range of house sizes and a diversity of architectural styles. [21] And like all places, it possesses three important features – some type of boundary, a place name, and its own individuality or uniqueness. Some localities have lost what made them distinctive places but Glebe has retained a strong sense of place. [22]

On the eve of the Great War, the Report of the Royal Commission for the Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs was a blanket condemnation of the pattern of life in inner Sydney, reinforcing the belief that the social and physical fabric of these areas were doomed to decay. [23] The word 'slum' was being used to describe the inner suburbs, delineating the territorial and social division between rich and poor. Like poverty itself, the label 'slum' has always been a relative thing, focussing on the decay of the physical fabric and the social image created. The existence of slums created a sense of uneasiness, because it challenged two strong assumptions about Australian society – that everyone made a comfortable living and that it was egalitarian. [24]

War, depression and relief

World War I was a time of trial and tragedy in Glebe. Etched in bronze in the foyer of Glebe Town Hall are the names of 792 local citizen soldiers who served overseas in the armed services. Traumatic as the war was in terms of personal grief and mourning (174 Glebe men died of wounds or were killed in action), the conflict also accelerated existing social, economic and political changes and exacerbated already entrenched divisions within society. [25] Mounting casualty lists turned simple patriotism at home into something much more grim and ugly; one symbol of xenophobic repression was the Glebe Anti-German League, which questioned the loyalty of anyone with a German name. [26] Two referendum campaigns, in October 1916 and December 1917, on the conscription of single men without dependants for war service, produced a revival of sectarian conflict and polarised the nation, and their defeat heightened tensions. And evangelical Protestants utilised the war to press for more temperance reform, inspired by the spirit of self-denial accompanying patriotic fervour, resulting in the introduction of 6 o'clock hotel closure in 1916. [27]

A working-class and wage-earning culture in Glebe in the first half of the twentieth century was distinguished by patterns of housing, work, consumption and recreation, and family households divided into breadwinners (mostly men) and dependants (mostly women and children). Neighbourhoods within the suburb offered families a chance to piece together the social fabric they needed in order to exist with some measure of security. Without the sustaining services of a welfare state, many sought out relatives, and lived either with or close to them. Kinfolk could be trusted in a way neighbours could not be, during periods of sickness, unemployment and old age. [28]

The Great Depression in Glebe came [media]early in 1929 when the timber strike began, and didn't really finish until the end of the 1930s. With 39.5 per cent of the Glebe male workforce listed as unemployed in 1933, listless bands of local people began to congregate on street corners, and from 1935 some gathered around the Wireless House to listen to 'specially selected programmes'. [29] Glebe Council nurtured a spirit of self-help by making small [media]grants to the Glebe Brass Band, the local Distress Society, St Vincent de Paul and other bodies. [30]

Poet Judith Wright recalled of her university days in the 1930s:

I moved to an upstairs room in a terrace house in Glebe. There was neither bath nor shower, the landlady indicating that the backyard washtub provided all a Christian should need (she was stronger on Godliness than cleanliness). [31]

Some strolled along Glebe Point Road singing doggerel:

When my hair turns blue mouldy,

I'll still be on the dole

And on Monday morning to Glebe Town Hall I'll stroll,

When my hair turns blue mouldy,

I'll still be on the dole. [32]

Once in winter, and again in summer, local people went upstairs in Glebe Town Hall where certain items were laid out on tables. Men received a shirt and boots while women and children received underwear, shoes and a few yards of dress material. [33]

Unemployment evaporated with the outbreak of war in 1939, but it disrupted and constricted peacetime patterns; for half a decade normal life was suspended. Almost 12 per cent of Glebe's population, some 2,347 men and 79 women, enlisted for service in the war, of which 81.5 per cent joined the Army.

Newcomers and activists

At the 1947 census Glebe and the [media]other inner suburbs remained industrialised and working-class in composition, and Glebe's population of 20,510 was overwhelmingly Australian-born. [34] But the advent of non-British migration, especially from Italy and Greece, meant the homogeneous culture of the Anglo-Celtic era began to fade as ethnic diversity broadened. The number of overseas-born residents in Glebe rose from 148 in 1947 to 3,420 in 1971. [35] The inner city entered a period of long population decline, and Glebe was described as a transit camp where 'families pause long enough to save money to buy a home and then move on'. [36] A steady exodus of young couples attracted by the prospects of owner-occupancy in outlying areas was reflected in declining public school enrolments. Between 1955 and 1975 the number of students at Glebe school fell from 882 to 350, and the number of Forest Lodge students declined from 445 to 232. [37]

Community participation in the 1960s led inner-Sydney communities to begin forming opinions of their own about the quality of their environment, and to cultivate new awareness of the history of their neighbourhoods. On planning maps, Glebe was coloured in as a zone of blight with two expressway corridors earmarked, with official sanction, to carve through its heart. Resident action groups were formed at Paddington (1964), Balmain (1965) and Glebe (1969), largely composed of young, usually tertiary-educated, socially aware people, often with salaried jobs in large companies, universities or the public service, and they agitated against serious threats to the character of their townscapes. A more vigorous style of pressure politics at the municipal level accompanied the entry of new residents, and they captured some Australian Labor Party branches. [38]

Resident action over the quality of life in the 1970s was defensive in nature, ranging from opposition to proposed expressways to action to protect inner-city housing. The enemies were the state government's Department of Main Roads (DMR) and developers intent on constructing brick walk-up units. Two threats to Glebe's townscape – urban radial expressways and the building of flats – preoccupied the Glebe Society in its early days. The DMR had acquired 80 Glebe properties by 1969 when the Glebe Society was formed. [39] The route of the North Western expressway conveniently avoided the dog track at Wentworth Park but threatened the old mansion Lyndhurst in Darghan Street, which became a symbol of the anti-expressway movement. The Builders Labourers Federation, led by Jack Mundey, imposed a 'green ban' on construction of the expressway. Green bans represented an alliance between militant trade unions and middle-class conservationists, and the movement took on the classic features of an urban social movement; it was sudden, unexpected and spontaneous, and its impact was dramatic. Expressway opposition took the form of confrontation at demolition sites and squatting at DMR-affected properties. After several confrontations between the Builders Labourers Federation, anti-expressway groups, police and demolishers in 1972, the DMR withdrew from Glebe. [40]

But the Liberal/Country Party Askin state government was determined to push ahead with expressway work. It ordered the DMR to move into Fig Street in Ultimo with bulldozers, chains and police, where they were confronted by a variety of groups. The Fig Street confrontation in 1974 received national coverage, and the Federal government withdrew funding for urban arterial roads, including the North Western, thus halting further demolition work. [41] For Glebe residents it was a sweet victory, and several months later in November 1974 the Glebe area was listed by the National Trust as a Conservation Area, receiving the highest category of listing. In the same year the Federal government acquired Bishopthorpe and St Phillip's estate from the Church of England. It was a venture notable for the scale of the project (723 properties used as family dwellings and 27 commercial buildings), for retaining a tract of Glebe inhabited largely by low-income families, and for being the first example of government acquisition of property to rehabilitate rather than redevelop. [42]

The return of the gentry

There was an intuitive feeling among long-time residents from the late 1960s that a social and physical transformation had begun in inner Sydney, and Paddington, Balmain and Glebe were among the first areas to experience a phenomenon later called 'gentrification', a term borrowed from the housing scene in inner London. The city, once a location of working-class employment in factories, was becoming exclusively a place for middle-class employment in large offices; critical to this transition from an industrial to a corporate city was redevelopment of the central business district. [43] A growing number of young professional and administrative people, working in the central business district, were attracted to the older type of inner-city housing that fitted in with the fashionable idea of heritage conservation. At every census between 1966 and 1986 there was a steady upward shift in the number of professional and technical workers moving into Glebe. This occupational group rose from 7.3 per cent of the population in 1966 to 12.6 per cent in 1971, 18.7 per cent in 1976, 26.7 per cent in 1981, reaching 36 per cent in 1986. At the same time, blue-collar workers were moving out, their numbers reducing from 46.9 per cent in 1966 to 24.1 per cent by 1986, when Glebe housed 11,484 people. [44]

Glebe and other inner suburbs have had their ups and downs over the last 170 years. They began as semi-rural resorts of the well-to-do and, with a renewed appreciation of city life, their transformation might be perceived as something like a return to their origins. Glebe has been reshaped through a convergence of the market forces of gentrification and the entrepreneurial initiatives of state and local governments. It has been transformed into a place where people consume its heritage ambience, with eating places, upmarket shopping and alternative lifestyles. [45]

References

Max Solling, Grandeur and grit: a history of Glebe, Halstead Press, Ultimo NSW, 2007

Notes

[1] RJ Lambert, 'Aboriginal Life Around Port Jackson 1788–1792', in B Smith and A Wheeler (eds), The Art of the First Fleet and Other Early Australian Drawings, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1988, pp 19–69

[2] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 1 Part 2, Grenville to Phillip, 24 August 1789, Encl. Phillip's additional instructions, 20 August 1789, p 259

[3] Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, p 35

[4] Doug Benson & Jocelyn Howell, Taken for Granted: The Bushland of Sydney and Its Suburbs, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 1990, p 61

[5] JF Campbell, 'Notes on the Early History of the Glebe ', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 15, 1929, p 301

[6] R Mansfield, Analytical View of the Census of New South Wales for 1841, Kent and Fairfax, Sydney, 1847, p 49

[7] Report of the Select Committee on Slaughter Houses, New South Wales Legislative Council Votes and Proceedings, 1848, pp 426–28, 433–435

[8] Church and School Corporation, Land Account Book 1827, 1829, vol 1, State Records New South Wales, 7/2708

[9] GWD Allen, Early Georgian: Extracts from the Journal of George Allen 1800–1877, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1958, p 120; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 May 1864

[10] Sydney District Council Assessment Sheets, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, D67

[11] R Mansfield, Analytical View of the Census of New South Wales for 1841, Kent & Fairfax, Sydney, 1847, p 11

[12] WS Jevons, 'Remarks Upon the Social Map of Sydney, Investigation into the City of Sydney 1858 and Pyrmont, Glebe, Camperdown, Sydney, 1858', State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, B864

[13] New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings, 1862, vol 3, p 658

[14] Max Solling, 'Bishopgate Estate 1841–1861', Leichhardt History Journal, no 1, 1971, pp 14–17

[15] R Jackson, 'Owner Occupation of Houses in Sydney 1871 to 1891' Australian Economic History Review, vol 10, no 2, p 148

[16] Bernard and Kate Smith, The Architectural Character of Glebe, University Co-operative Bookshop, Sydney, 1973, pp 70–90

[17] Max Solling, 'Biographical Register of Glebe Local Elected Representatives, (unpublished), Glebe Lodge No 96, 1881–1981: A Review of the First 100 Years of Glebe Lodge, 1981 p 24

[18] 1901 Census, Journal of New South Wales Legislative Council, 1902, part 2, p 1179

[19] J Hagan and K Turner, A History of the Labor Party in New South Wales 1891–1991, Longman Cheshire, Melbourne, 1991, p 259

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 December 1925 pp 3, 11; Daily Telegraph, 7 December 1925 pp 1,5; Max Solling, 'The Labor Party in Inner Sydney', Leichhardt History Journal, no 22, 2000, pp 3–10

[21] RJ Johnston et al (eds) The Dictionary of Human Geography, Fourth Edition, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2000, pp 582–585

[22] Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness, Pion, London, 1976

[23] Report of the Royal Commission for the Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs, New South Wales Legislative Assembly Votes and Proceedings 1909, vol 5, pp 379–703

[24] Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp: Sydney 1870–1890, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, p 8

[25] Max Solling, Card Index of Glebe Men Killed in the 1914–1918 War

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 January 1916, p 16

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 June 1916, p 10

[28] Annie Fairs, Evidence to Inquiry on the Cost of Living and the Living Wage, NSW Industrial Arbitration Court, 1913, State Records New South Wales 6/17670/1 Mary Ann Dunn, Evidence to Royal Commission on the Basic Wage, Government Printer, Sydney, 1920, p 984

[29] Daily Telegraph, 22 February 1935, p 5

[30] Glebe Municipal Council, Minutes, 6 February 1930, p 130

[31] J Wright, 'Forty Years and Australian Cities, Community, No 7 (February 1975) pp 2–3

[32] Reg Burbury, interview with Max Solling, 19 April 2008

[33] Noeline Reddie, interview with Max Solling, 10 June 2008

[34] Commonwealth Census, 1947, vol 1, pp 44, 52

[35] Katherine Gibson, 'People and their Place', BA honours thesis, Dept of Geography, University of Sydney, 1975, p 80

[36] Max Solling & Harry Wark, Under the Arches: A History of the Glebe District Hockey Club to 1993, Glebe District Hockey Club, 1994, p 53

[37] Abstract of Returns of School Attendance, 1955, 1975, State Records New South Wales

[38] JW Power, 'The New Politics of the Old Suburbs', Quadrant, 13 (1969) pp 60–65; A Jakubowicz, 'A New Politics of Suburbia', Current Affairs Bulletin, April 1972, pp 538–551

[39] Hal Kendig, New Life for Old Suburbs, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1979, p 147

[40] R Cain, 'Transportation, Planning and Conflict in Sydney: A Case Study of Inner City Expressways in Glebe', B Sc thesis, University of New South Wales, 1975, pp 65–72

[41] R Cain ,'Transportation, Planning and Conflict in Sydney: A Case Study of Inner City Expressways in Glebe', BSc thesis, University of New South Wales, 1975, pp 85–86

[42] C Wagner, 'Sydney's Glebe Project: An Essay in Urban Rehabilitation', Royal Australian Planning Institute Journal, vol 15 no 1 (February 1977) p 5

[43] Robert Fagan, 'Industrial Change in the Global City: Sydney's New Spaces of Production', in John Connell (ed), Sydney: The Emergence of a World City, Oxford University Press, New York, 2000, pp 148–149

[44] B Engels, 'The Gentrification of Glebe: The Residential Restructuring of an Inner Sydney Suburb 1960to 1986', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1989, pp 340–342

[45] The City Residents Guide, City of Sydney Council, 2006, pp 92–93

.