The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

East Timorese

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

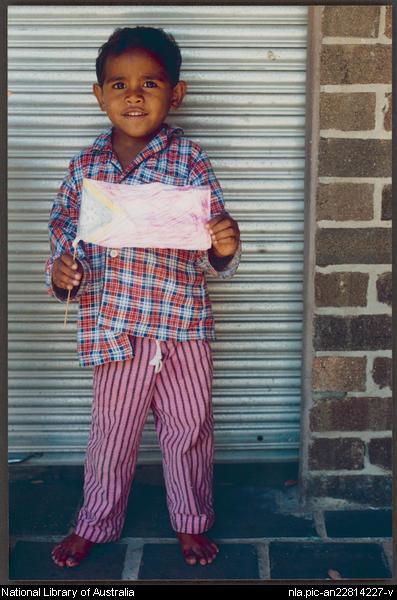

East Timorese

A boy befriended a sick crocodile and carried it to the sea. In gratitude, the crocodile took the boy on many journeys across the sea. As it grew old and approached death, the crocodile said: 'I will change into a land where you and your descendants will live from my fruits, as payment for your kindness.' According to legend, the land was the island of Timor and the descendants were the Timorese.

[media]East Timor is the world's newest democracy and Australia's nearest neighbour. The first president of the independent nation in May 2002 was the former resistance leader Xanana Gusmâo who married Australian activist Kirsty Sword in 2000. He became the country's fourth Prime Minister on 8 August 2007.

Timor, meaning 'east' in Indonesian, is a narrow mountainous island at the south-eastern end of the Indonesian archipelago. Half the island was colonised by the Portuguese in the seventeenth century and remained so when the western, formerly Dutch, half joined the newly independent Indonesian republic in 1945. East Timor is now called Timor-Leste in Portuguese and Timor Loro Sa'e in Tetum, the two official languages. The East Timorese are culturally and linguistically distinct from Bahasa-speaking Indonesians in the western half of the island.

Waves of refugees

In 1975, Portugal withdrew from its neglected colony and, on 7 December, the Indonesian army invaded with devastating military force. Many East Timorese fled to Australia to escape a civil war and a violent and repressive Indonesian regime. Most refugees settled in Sydney, in government accommodation at Coogee, Cabramatta and later Villawood Hostel. Between 1976 and 1981, 2,447 arrived, of whom 1,940 were Timorese Chinese. Many came under a specially implemented family reunion program. The Dili massacre of November 1991 created further internal unrest and another wave of 1,650 refugees fled to Australia between 1994 and 1996.

In August 1999, after 25 years of clandestine resistance, the people of East Timor were offered a referendum on their future by the Indonesian president. When they voted overwhelmingly for independence, Indonesian-backed militia went on a violent rampage. A new influx of refugees arrived from September 1999 when the Australian government offered temporary refuge to almost 2,000 East Timorese evacuees, including 350 staff of the United Nations Mission in East Timor and some 1,500 people who had sheltered in the UN compound. [media]In Sydney, evacuees were accommodated at the East Hills army barracks, formerly a safe haven for Kosovar refugees. Here they had access to health care, clothing and food, trauma counselling, education and English-language training. They received a small weekly allowance from the government but, with East Timor no longer annexed by Indonesia, they could not claim asylum status or apply for permanent residency.

[media]At the 2001 census, there were an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 East Timorese in Sydney. Many of them are second-generation children who were born here. Their different ethnic affiliations reflect those in their homeland – 61 per cent were Chinese, 40 per cent Timorese, and 10 per cent Portuguese. Most recent arrivals speak Bahasa Indonesia, the only permitted language under Indonesian rule, and many are bilingual but do not speak English.

Over the years, about half of Sydney's East Timorese community settled in the Liverpool/Fairfield area. [media]These included diplomat and future Nobel Peace Prize winner José Ramos-Horta and his family. About one-quarter live in public housing in Botany and Randwick. Nearly all arrived under humanitarian and refugee programs and most have been here for over 10 years. With their impoverished rural background and uncertain future, these displaced and traumatised families face significant problems adjusting to urban Australian life, but many have built lives for themselves and achieved success while maintaining their cultural heritage. Those with legal status now return periodically to East Timor, while others have moved back permanently to help their nation rebuild.

Religion

The Portuguese brought Catholicism to East Timor in the sixteenth century but a strong animist tradition survived until 1975. Approximately 95 per cent of the East Timorese in Sydney are Catholic and the church provides essential community support. Another organisation is the Mary MacKillop Institute East Timor, formerly the Mary MacKillop Institute for East Timorese Studies, founded by the Sisters of St Joseph in 1993. It runs literacy, teaching and health programs in Sydney and Dili.

Community help

The Timorese Australian Council was created in 1986. It helps East Timorese refugees and migrants to settle, promotes Timorese culture, and advocates for the East Timorese community. The Australia East Timor Association, formed in Sydney in 1992, claims to be the first and longest serving solidarity organisation for East Timor in Australia.

Now located at Fairfield, the East Timorese Cultural Centre was founded in 1984 to promote the East Timor cause and culture. The centre passes on knowledge from the older generation to Timorese youth, provides basic teaching skills in Tetum, and teaches dance and English.

Timorese-Chinese

The Chinese in Timor belong to the Hakka-speaking diaspora. The first Timorese-Chinese arrivals in 1975 were wealthy families from Dili who were housed in the Endeavour Migrant Hostel at Coogee. Later refugees went to the Cabramatta Migrant Hostel where they formed a cohesive community that is quite distinct from non-Chinese Timorese and from other Chinese communities. They founded the Timorese-Chinese Association, now located at Greenfield Park near Liverpool. It runs Chinese and Portuguese dance classes, Mandarin classes, sports activities, celebrates Chinese festivals, and organises annual gatherings of all Timorese-Chinese in Australia. Although many Timorese-Chinese worship at the Laotian Buddhist temple in Bonnyrigg and others have married Portuguese spouses, they retain their own sense of identity.

Culture and heritage

Leaving the Crocodile was an exhibition based on a Timorese creation legend held at several Sydney locations in 2007. [media]It enabled the East Timorese to tell their stories of struggle, migration and exile. Other events in Sydney have reinforced Timorese pride in their culture. For 12 months to May 2001, two East Timorese artists, Brigida de Andrada and Manuel Branco, conducted weekly art workshops for East Timorese youth at the East Timor drop-in centre in Fairfield. Since its closure, community meetings are held at the Casula Powerhouse museum.

Singing, dancing and theatre performances are significant elements of East Timorese culture and identity. The distinctive tais or colourful woven cloths are an integral part of traditional dance dress and have become ritual objects in the prolonged East Timorese struggle for independence.

East Timorese are keen sportspeople. Despite a lack of funding and basic necessities, four East Timorese competitors came to the Sydney Olympics in 2000 where they were supported by the Timor Australia Council and a sympathetic public.

References

Australia Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, Annual Report, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1999–2000

Australia East Timor Association New South Wales, 'Newsletter No 1', April 2001, the association, Darlinghurst NSW, viewed 21 November 2008, http://members.pcug.org.au/~wildwood/01apraeta.htm

Back door, 'Newsletter on East Timor', Back Door, Kaleen ACT, viewed 21 November 2008, http://members.pcug.org.au/~wildwood/

Leaving the Crocodile: The Story of the East Timorese Community in Sydney, Liverpool Regional Museum, Casula NSW, 2001

Parish Patience Immigration Lawyers, Australian Immigration Law Update Newsletter, no 14, October 1999

Timorese Australian Council, Settlement of the East Timorese Community in New South Wales, Ettinger House, Sydney, 1994

Amanda Wise, 'Embodying Exile: trauma and collective identities among East Timorese refugees in Australia', in Social Analysis, vol 43 no 3, fall 2004, pp 24–39, viewed 21 November 2008, http://www.crsi.mq.edu.au/people/staff/documents/socialanalysis-embodyingexile.pdf

Amanda Wise, Exile and Return Among the East Timorese, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 2006