The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Croydon

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Croydon

Croydon is a suburb approximately 10 kilometres from central Sydney. It is situated between two highways (Parramatta Road and Liverpool Road), it is bisected by the railway and railway station, and it lies between the retail and commercial centres of Ashfield and Burwood. It is bounded on the north by Parramatta Road, on the east by Iron Cove Creek and Milton Street, on the south by Arthur Street, and on the west by a number of streets separating it from Burwood.

The landform rises from the low-lying areas around Iron Cove Creek to Liverpool Road, which runs along a substantial ridge and divides the watersheds between the Parramatta and the Cooks River catchments. The predominant rock of the area is Ashfield shale, a unit of the Wianamatta group of shales. The Wianamatta group overlies Hawkesbury sandstone and represents the most recent of Sydney's sedimentary rocks. The soils are predominantly heavy clays, derived from the underlying shale. It is thought that the original vegetation of the area was turpentine-ironbark forest, of which virtually nothing now remains. Some eucalypts survive in Cheltenham Road, in a newly developed park on the former site of the Burwood Brickworks. These may possibly be descendants of the original flora of the area, but the rest has been ruthlessly exterminated. [1]

The original inhabitants of the area were the Dharug-speaking Wangal clan, whose land stretched along the southern shore of the Parramatta River from Darling Harbour to Parramatta and south to the Cooks River. There are no known Aboriginal sites in Croydon, but there are rock shelters and middens on both the Parramatta and Cooks rivers. [2]

Europeans arrive

With the establishment of a penal colony in Sydney in 1788, enormous changes were wrought on the Sydney basin. A small settlement was established at Rose Hill (later known as Parramatta) in 1788. Initially traffic between Sydney and Parramatta was by water, but a rough track soon developed. By 1791 this track followed a similar route to the modern Parramatta Road, skirting the swamps on the southern edges of Iron Cove and Hen and Chicken Bay. A map drawn by William Dawes in 1791 is the first written record of the area known as Croydon. His map was annotated with the comment that it was 'a tract of good land to appearance in many places hereabout'. [3]

By 1793 a stockade had been established halfway between Sydney and Parramatta, near the current site of St Luke's Oval (on the northern side of Parramatta Road), as an overnight resting place for the convict working parties. In October of that year, Governor Grose sent workmen and convicts there to form a timber yard. Soon 60 acres (25 hectares) had been cleared of timber and by 1821 what had become known as the Longbottom Government Farm extended over 700 acres (283 hectares) of land, covering much of modern Concord.

In 1822 Commissioner Bigge gave a detailed description of the area. Longbottom, he noted,

contains some valuable timber, which is cut and sawn upon the spot and conveyed to Sydney in boats by the Parramatta River, on the southern side of which part of the farm of Longbottom is situated. Charcoal for the forges and foundries is likewise prepared here, and as the land is cleared of wood the cultivation is extended under the direction of an overseer who was a convict and has received his emancipation. [4]

The first settlers followed soon after the establishment of Parramatta Road. Sarah Nelson, the free settler wife of convict Isaac Nelson, was granted 15 acres (6 hectares) in the vicinity of Malvern and Dickinson avenues in 1794. By 1806 she and Isaac had cleared 11 acres (4 hectares) and the farm supported two of their four children. In 1809 Isaac was granted 100 acres (40 hectares) of land on Prospect Creek (now Fairfield) and the family moved, Sarah probably dying there in 1817.

Small grants of 25 and 30 acres (10 and 12 hectares) were also made to James Brackenrigg, Denis Connor and James Eades along Parramatta Road. Lieutenant John Townson and Augustus Alt were each granted 100 acres (40 hectares) in 1793 and 1794 respectively, to the east of Eades's land grant. [5]

These early grants were dwarfed by the 250 acres (101 hectares) granted to Captain Thomas Rowley in 1799. This grant, later extended to 750 acres, (304 hectares) covers most of Burwood and Croydon. Rowley, like Townson, an officer in the New South Wales Corps, was living at Kingston Farm (in modern Annandale) and never resided on his grant.

Roads and railways

In 1813 a road connecting to the new town of Liverpool, on the Georges River, was first mooted. Construction commenced in 1814 and it was completed by May 1816, when tolls were being levied on the new road. Several hotels were built on Liverpool Road, including the Dove Inn, near the modern intersection with Croydon Avenue. The area remained lightly settled however. In 1848 the parish of Concord (including all of modern Concord, Burwood, Croydon and Enfield) had 216 houses and a population of 1172. [6]

The construction of the first railway line in New South Wales, from Sydney to Parramatta Junction (near Granville Station), bisected the Croydon area. The line was opened on 26 September 1855, with intermediate stations at Newtown, Ashfield, Burwood and Homebush. Subdivision and settlement began in Croydon, though the distance to Ashfield and Burwood stations, and the poor state of the roads, restricted development.

In northern Croydon, Henry Richard Webb built a villa called Cicada (which still stands in Queen Street) in 1863. Captain Henry Fox built Evandale (now the site of Blair Park) in 1868. John Dawson bought most of Connor's grant as well as other surrounding land and in about 1869 built a large villa called Humberstone between Queen Street and Parramatta Road. Anthony Hordern, who developed extensive landholdings north of the railway line, built Shubra Hall just north of the railway line at Croydon in about 1869. [7] Gadshill Villa in Highbury Street (on the south side of the railway) was built in the 1860s by L Bergin. [8]

Development of the area was given a huge boost with the opening of a railway station in January 1875. Five Dock station, as it was originally known, was the first new station built on the line since Haslem's Creek (Lidcombe) in 1858. Anthony Hordern and Henry Fox had both agitated on this matter since the late 1860s and with Daniel Holborow's purchase of Gadshill Villa and Walter Friend's purchase of the Cintra Estate, it was clear that despite the sparse population of the area,

a few favoured individuals have had sufficient influence with the powers that be to obtain the creation of the platform…situated less than half a mile beyond Ashfield. [9]

Croydon emerges

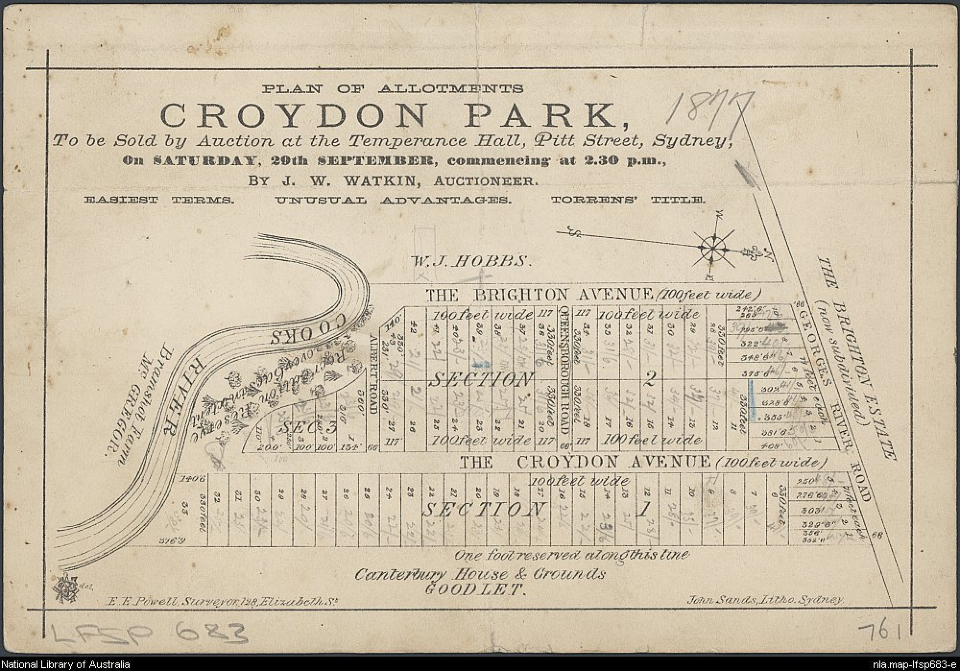

[media]Shortly afterwards, Henry Parkes purchased a portion of Brighton Farm, south of Georges River Road, between Brighton and Croydon avenues. He renamed it Croydon Park and began planning a subdivision. In August 1876 Five Dock station was renamed Croydon station, and Parkes's subdivision was auctioned in September as the Croydon Park Estate. It is unknown whether Parkes engineered the name change, or was simply aware that it was going to happen and acted accordingly. What is clear is that the naming of Croydon station and the subdivision of Croydon Park Estate are intimately linked. [10] It is not known who chose the name Croydon, but it is likely that the thriving railway suburb of Croydon in London was the inspiration for the name.

A village soon sprang up around Croydon railway station, mainly to the north, centred on Edwin Street and Elizabeth Street. An attractive Congregational church was built in Edwin Street, terminating the western vista down Elizabeth Street. Shops and businesses sprang up in Elizabeth and Edwin streets to serve the growing population. In 1879 Croydon was described as

an agreeable bit of home scenery; diversified by gardens and trees…where nature has not yet been ruthlessly improved away. Streets (for the most part mere lanes) intersect this tract, whereon stand villas and gardens belonging to Sydney people, displaying a considerable amount of domestic comfort, originality, and even elegance of design. Vistas of pleasant country roadways, green, and as yet innocent of dust and mire, stretch up the gentle eminences to the left and right. [11]

Even before the station opened, the Orchard and Field Estate (including Robinson, Young and Wright streets) was subdivided in 1870, though few blocks were sold. It was resold as the Windsorville Estate in 1880. [12] On the south side of the railway, the large estates of Daniel Holborow (Gadshill), Samuel Dickinson (The Hall), George Murray (The Lea) and Walter Friend (Cintra) effectively prevented any development. Devonshire Street, which was subdivided as the Chatsworth Estate in 1881, was a failure, as residents had to walk up to Liverpool Road and then down Edwin Street to reach the station without crossing private property. It was not until 1911, with the subdivision of the Malvern Hill Estate, that Devonshire Street residents could take a direct route to the station.

Industry and services

The main industry in the area at this time was brickmaking, as the clay and shale of Croydon formed ideal raw material for the making of bricks, eventually leading to the development of deep and extensive quarries. William Keen operated a brickyard in Queen Street (now the site of Ashfield Centenary Sports Area) from about 1873. Later enlarged, these works became the Excelsior Brickworks, which operated from about 1890 to 1918. In the mid-1870s, Anthony Hordern also established a brickworks, in Webb Street. Later known as the Croydon Steam Brick Company, these works operated until about 1930. Subsidence into the deep shale pit of these works swallowed a portion of the grounds of Croydon Public School (and the fence) in 1930, possibly hastening its closure. The Burwood Brickworks in Cheltenham Road, the last major brickworks established in Croydon, was opened in 1913. These works operated until about 1970, and their closure marked the end of brickmaking in Croydon. [13]

The growing population in Croydon led to the opening of Croydon Public School in February 1884. This was followed in 1891 by the move of Presbyterian Ladies' College from Ashfield to Shubra Hall. In 1892, an overhead bridge at Meta Street superseded the old level crossing at Edwin Street, but traffic still had to access Liverpool Road via Edwin Street, because of the private landholdings of Murray, Dickinson and Friend. In 1893 the Western Suburbs Cottage Hospital was opened, on the corner of Brighton Street and Liverpool Road. A vigorous local campaign had raised funds for the land purchase, and when the hospital was opened it was free of debt.

Residents of Croydon

Prominent local citizens included Frederick Eccleston Du Faur, a surveyor and scientist, who resided in Grosvenor Street, and later Walter Froggatt, a government entomologist, who lived in Queen's Crescent (later named Froggatt Crescent in his honour). A number of substantial villas were built along Liverpool Road. Perhaps the largest was Roslyn Hall (now St Joseph's Convent), which belonged to William Hudson, a well-known timber merchant. Iruak (Kauri spelt backwards), on the corner of Croydon Avenue, was built for Robert Walker, manager of the Kauri Timber Company. Other villas included Tahlee and Wynola, designed by John Horbury Hunt in 1883 for the grazier Andrew Broad. [14]

Development and change

From 1909, the development of the Malvern Hill Estate finally opened up the portion of Croydon between the railway line and Liverpool Road. Quickly thereafter the subdivision of the Cintra Estate was begun. As part of this development in Brady, Fitzroy and Rosa streets, a unique collection of 20 concrete houses were built by the Camerated Concrete Company, using a system devised by Henry A Goddard, a Concord builder, inventor and associate of. Arthur Gilbert Friend (who inherited the Cintra Estate from his father Walter Friend). This is believed to be the largest group of concrete houses built anywhere in Australia before World War I. [15]

By the early 1920s little land remained in Croydon, though there was a 'fair amount' of subdivided land for sale and prices were high (up to £10 per foot of frontage in Malvern Hill). [16] Small pockets of land were occasionally released, mostly from the demolition of villas and the subdivision of their grounds. One of the last of these was the demolition of the villa Tahlee at the southern end of Tahlee Street, in 1955. [17]

By this time Croydon had become a favoured destination of post-World War II immigrants. A Russian Orthodox church was set up in a house in Chelmsford Avenue. Another house in Brady Street became the headquarters of the German Catholic Church in Sydney in the 1950s. In 1972 they purchased the Congregational church in Elizabeth Street, which became St Christophorous Church. In more recent years, the Croydon Masonic Hall has become the Imar Youth Charitable Hall, owned by a Lebanese Maronite charitable organisation.

Despite an intensive local campaign, the Western Suburbs Hospital was closed in 1994 and demolished shortly thereafter (presumably to preclude any possibility of reopening). A new health facility was built on the Liverpool Road frontage, after sitting idle for nearly 10 years.

Conserving Croydon's heritage

Large portions of Croydon have become conservation areas. Starting with the Malvern Hill Estate in 1983 (one of the earliest recognised conservation areas in New South Wales after Paddington and Haberfield), almost all of Croydon between the railway and Liverpool Road has been protected, contrasting with the intensive development occurring in Grosvenor Street and Webb Street, north of the railway. Likewise a large part of north Croydon has been earmarked for preservation.

The unique character of Croydon is now largely protected by conservation areas, but still provides 'a considerable amount of domestic comfort.' [18] Thus Croydon seems destined to remain an attractive and desirable residential suburb.

References

Eric Dunlop, Between two highways: the story of early Croydon, Wentworth Books, Surry Hills NSW, 1969

Nora Peek and Chris Pratten, Working the clays: the brick-makers of the Ashfield district, Ashfield and District Historical Society, Ashfield, 1996

Notes

[1] Doug Benson and Jocelyn Howell, Taken for granted: the bushland of Sydney and its suburbs, Kangaroo Press in association with the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, Kenthurst, 1990, pp 52–53

[2] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal past: investigating the archaeological and historical records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2002, p 25

[3] FM Bladen, (ed), Historical records of New South Wales, Charles Potter, Government Printer, Sydney, 1891, vol 1, p 164

[4] John Bigge, Report of the Commissioner of Inquiry into the state of the colony of New South Wales, 19 June 1822, Facsimile, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1966, p 25

[5] Jean McNaught, Index and registers of land grants – leases and purchases 1792–1865, Richmond-Tweed Regional Library, Goonellabah, NSW, 1998

[6] WH Wells, A geographical dictionary or gazetteer of the Australian colonies, 1848, Facsimile, Council of the Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1970, p 130

[7] Eric Dunlop, Between two highways: the story of early Croydon, Wentworth Books, Surry Hills NSW, 1969, pp 31–33

[8] Sheena and Robert Coupe, Speed the Plough: Ashfield 1788–1988, Council of the Municipality of Ashfield, Ashfield, 1988, p 99

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 November 1874

[10] Lesley Muir, 'Shady acres: politicians, developers and the design of Sydney's public transport system 1873–91', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1995, pp 54–55

[11] The railway guide of New South Wales, Thomas Richards, Government Printer, Sydney, 1879

[12] Subdivision plans 811.1834, Mitchell Library

[13] Nora Peek and Chris Pratten, Working the clays: the brick-makers of the Ashfield district, Ashfield and District Historical Society, Ashfield, 1996, pp 74–85

[14] Peter Reynolds, Lesley Muir and Joy Hughes, John Horbury Hunt: radical architect, 1838–1904, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002, pp 124–25

[15] Chery Kemp, 'Henry A Goddard's Sydney concrete houses, 1905–25', Masters thesis, University of New South Wales, 1995

[16] MA Harris, (ed), Where to live: ABC guide to Sydney and suburbs, Marchant and Co, Sydney, 1917, p 90

[17] Subdivision plans 811.1834, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library

[18] The railway guide of New South Wales, Thomas Richards, Government Printer, Sydney, 1879

.