The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Coogee

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Coogee

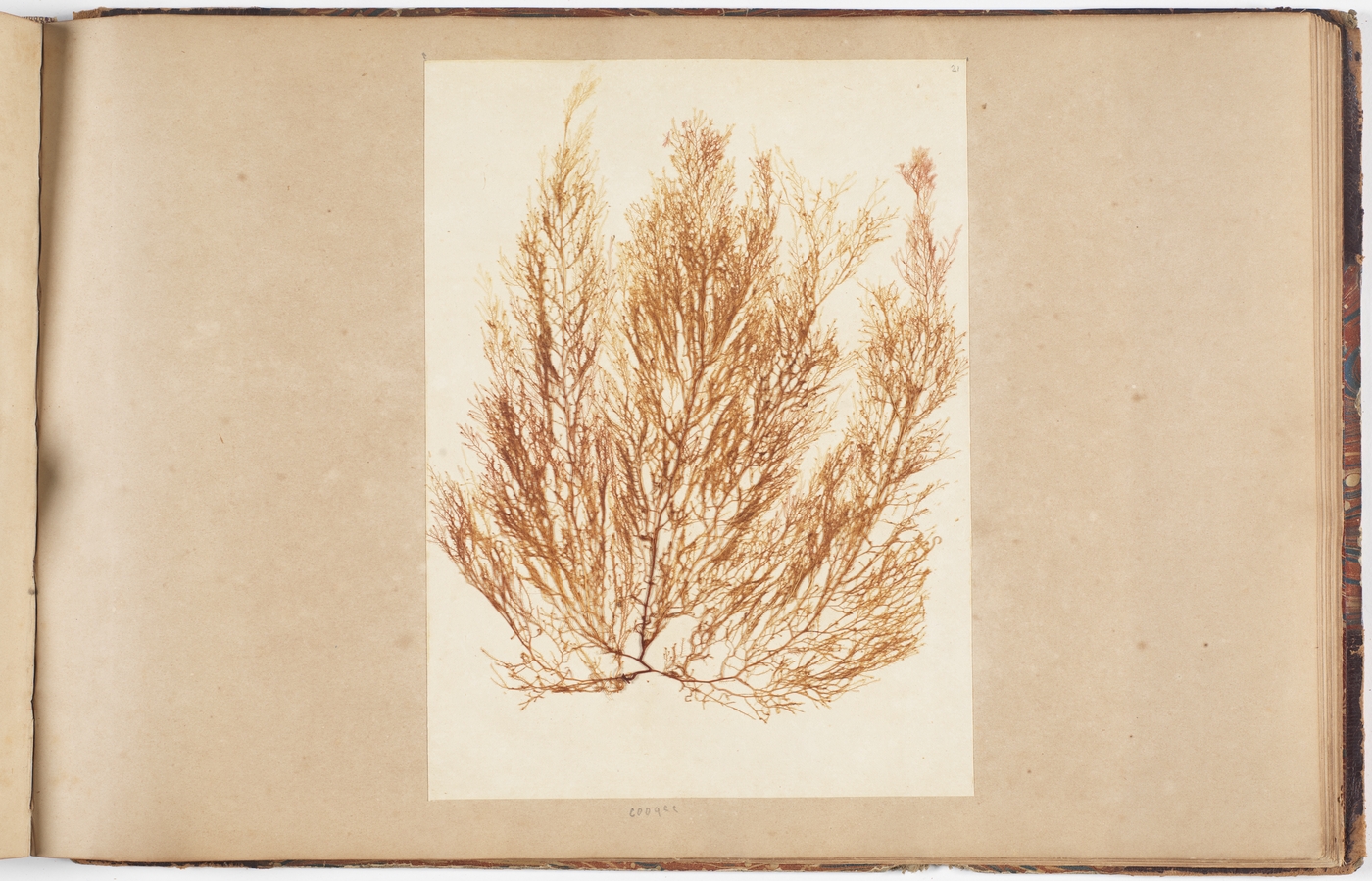

[media]The name Coogee is derived from the Aboriginal word 'koojah' which means 'bad smell' or a 'stinking place'. In 1950 the anthropologist Frederick McCarthy gave alternative spellings as 'Kuji' and 'Kudji' meaning 'bad generally; stinking; a bad smell'. [1] The area was so called because of the pungent smell of seaweed that regularly washed up on the shores of the beach.

[media]Before white settlement, the Aboriginal people who lived in the area found the ocean to be abundant with fish 'of all descriptions from the great whale to the little brim'. [2] On the land, which was thick with timber, kangaroos and wallabies were also prolific in the area and provided a further traditional food source for the local Aboriginal people.

Early European settlement

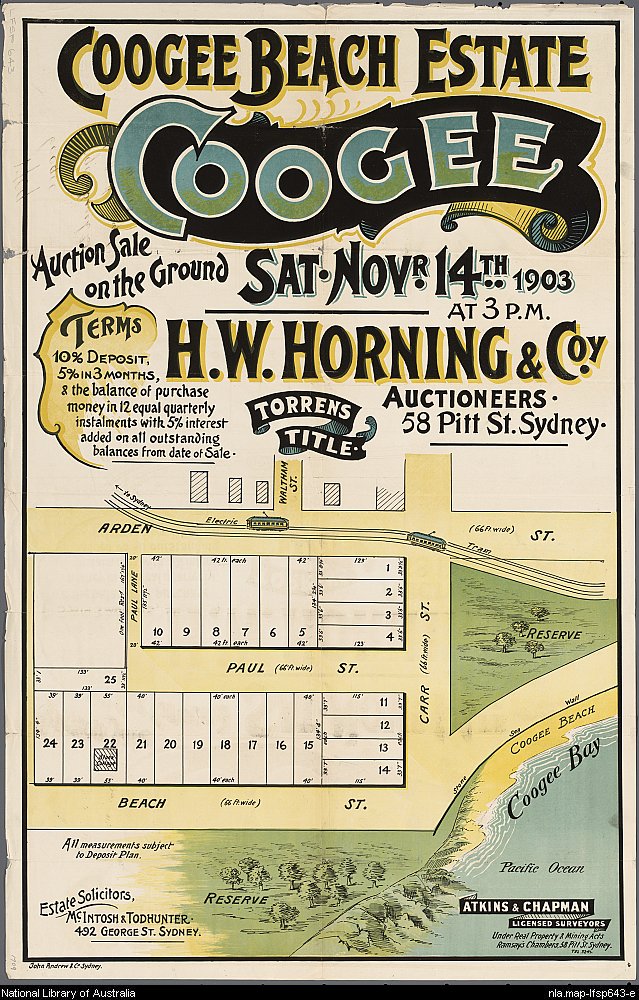

[media]In 1835 William Charles Wentworth bought 30 acres (approximately 12 hectares) at the head of Great Coogee Gully for £78. The land covered the area now known as Judge, Oswald and Dolphin streets and Carrington Road. [3] It was Governor Richard Bourke who first ordered that the land on the shores of Coogee Bay should be laid out in 1837; a year later the village of Coogee was gazetted. The new village was allocated into acre sites that were offered for sale at the markets on George Street, Sydney, in February 1840. [4] Yet development was slow and by 1858 there were still only 14 houses in Coogee. [5]

The genesis of a seaside resort

[media]By the following decade Coogee had become a popular destination for day trips, weekend excursions and family picnics. Some visitors came to swim, others to paddle or promenade, some just to sit and quietly observe the weekend crowds. In part, this increase in visitors was due to the completion of the road through Randwick in the late 1850s and after Randwick Council created a park on the northern end of Coogee beach in 1860 where picnics and cricket matches became regular weekend events. On the beach itself, shell collecting was all the rage in the 1860s and an interest in fossicking was seen as a particularly suitable outdoor pastime for the ladies.

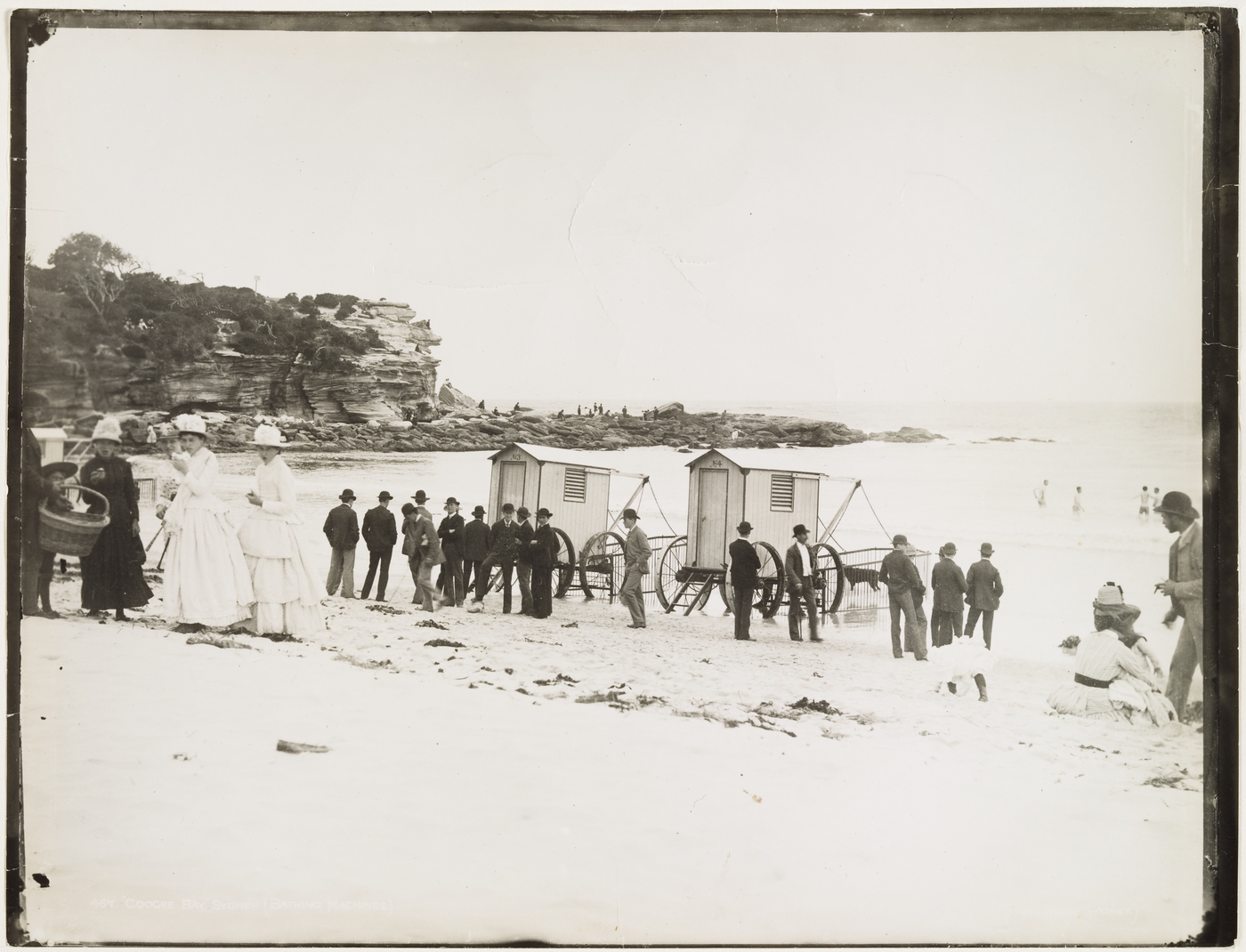

Ocean pools and bathing machines

Randwick Council [media]also established Sydney's first ocean pool at Coogee in the 1860s and ocean pools would remain an enduring feature of many Sydney's beaches. [6] Also in this decade, bathing machines first appeared on Coogee Beach. For those who preferred to swim in the sea rather than the sea pools, these sheds on wheels served as dressing rooms reflecting the social and moral mores of the day when swimming and being seen in a state of undress were deemed 'unrespectable'. The bathing machines allowed swimmers to undress and were pulled down into the shore to allow swimmers to slip into the water and thus remain largely unseen from the beach. The machines in particular maintained decorum for women who could discretely change into bathing clothes without being seen by male onlookers.

Transport and trams

[media]Even in the 1880s it seems Coogee village was a place to visit on the weekend rather than a place to live. By 1883 a tramline from the city to Coogee Bay carrying steam trams was completed. The tramline helped the steady stream of weekend visitors, however, it did not promote the by now well-established resort to become a place of residence. [media]As the Daily Telegraph declared in 1887:

It has often been a matter of conjecture why Coogee Bay, with all its natural advantages, should year after year remain neglected. One would expect that long ago the hills and shores would have been adorned with marine villas and terraced gardens instead of remaining as it does to this day, a mere fishing village with only a few wooden buildings and two hotels worthy of the name where visitors can procure refreshments after their long drive from the city. [7]

[media]The tram services converted from steam to electric in November 1902 running until the late 1940s when bus services began. The last tram left Coogee on Sunday 23 October 1960. [8]

The Coogee aquarium and swimming baths

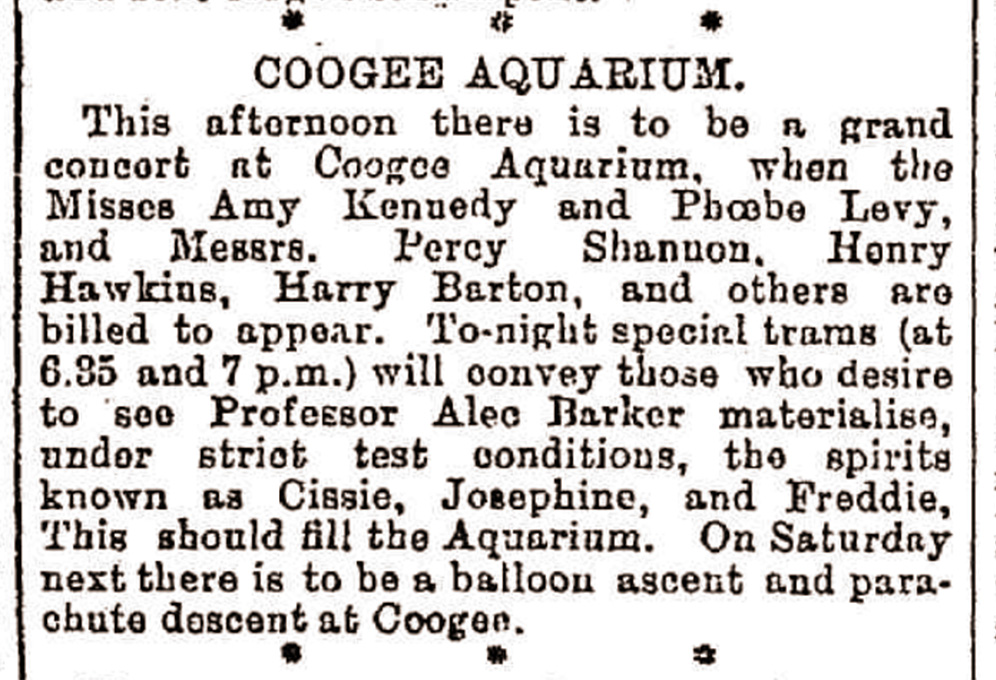

The Coogee Aquarium and Swimming Baths were built in 1887. The building was Italian in style with an incredibly ornate central octagonal dome. It was designed and supervised by the architect John Smedley and it was opened on 23 December 1887 with much fanfare and local excitement. The Sydney Morning Herald declared it to be a 'most exquisite addition to Sydney's places of entertainment…a most elegant building artistically arranged.' [9]

[media]Beyond the architecture, the Coogee aquarium soon became a popular entertainment centre rivalled only by Bondi and Manly. For the first time, people could watch seals, sharks and live fish swimming in the aquarium. Bandstands, flowerbeds, aviaries and an open-air bar also made it the place to visit. On 9 May 1889, The Sydney Morning Herald advertised the attractions at the Coogee Palace Aquarium that included, among other things, 'The World's Greatest Juggler, Mons Provo', 'The Northern Territory Aboriginals', the largest living alligator, four immense buffaloes, 14 donkeys, free skates '…and one hundred other attractions'. [10] The swimming baths were built indoors and the roof was partially open to allow the sun to heat up the water. On weekends double-decker steam trams carried excited crowds of Sydneysiders and visitors from further afield to the aquarium and the swimming baths.

The popularity of the aquarium at Coogee, like those elsewhere at Tamarama and Manly, did not last long once the initial novelty wore off. For most Sydneysiders, one visit was enough and the Depression years of the 1890s further contributed to their demise. [11]

In the 1980s, following years of neglect, the by now dilapidated building was heritage listed by the New South Wales Heritage Council in May 1982. It was subsequently renovated and renamed the Coogee Palace. [12]

Beach safety

[media]By the early twentieth century, and as swimming became more popular and indeed more acceptable to respectable society, the need for safety at the beach heightened. It was in this context that the Coogee Life Saving Brigade was formed in 1907. The following year the club began training at the Coogee Aquarium and in 1910 a new wooden clubhouse was built at a cost of £450. As surf bathing and swimming became even more popular in the 1920s, so too the surf club grew, and a prominent new building was constructed in 1929. [13]

The pier at Coogee

To cater for the growing popularity of the seaside and more particularly Coogee, in 1928 an amusement pier was built. It opened in July 1929 and extended for 183 meters into the sea. It included a 1,400 seat theatre, a ballroom for 600 dancers and an upstairs restaurant seating 400 people. The pier was constructed by the (somewhat unimaginatively named) Coogee Ocean Pier Company Limited and was designed by GLD James. Such was the level of excitement on the first day of construction that large crowds gathered to watch and radio stations 2BL and 2KY made live broadcasts of the proceedings. [14] On 24 July 1929, the pier opened with a huge gala and thousands flocked to be among the first to walk along this new Coogee landmark. [15]

[media]It was hoped that this feature, popular in the British seaside resorts of Blackpool, Brighton and elsewhere, would similarly provide a welcome attraction to the seaside suburb. On Sunday afternoons and evenings the pier was lit up and orchestras and popular singers entertained the dancing crowds. However, despite assurances that the pier would be stronger than any built in England, [16] rough seas ensured that it only lasted for a few short years. It was demolished in 1934. [17]

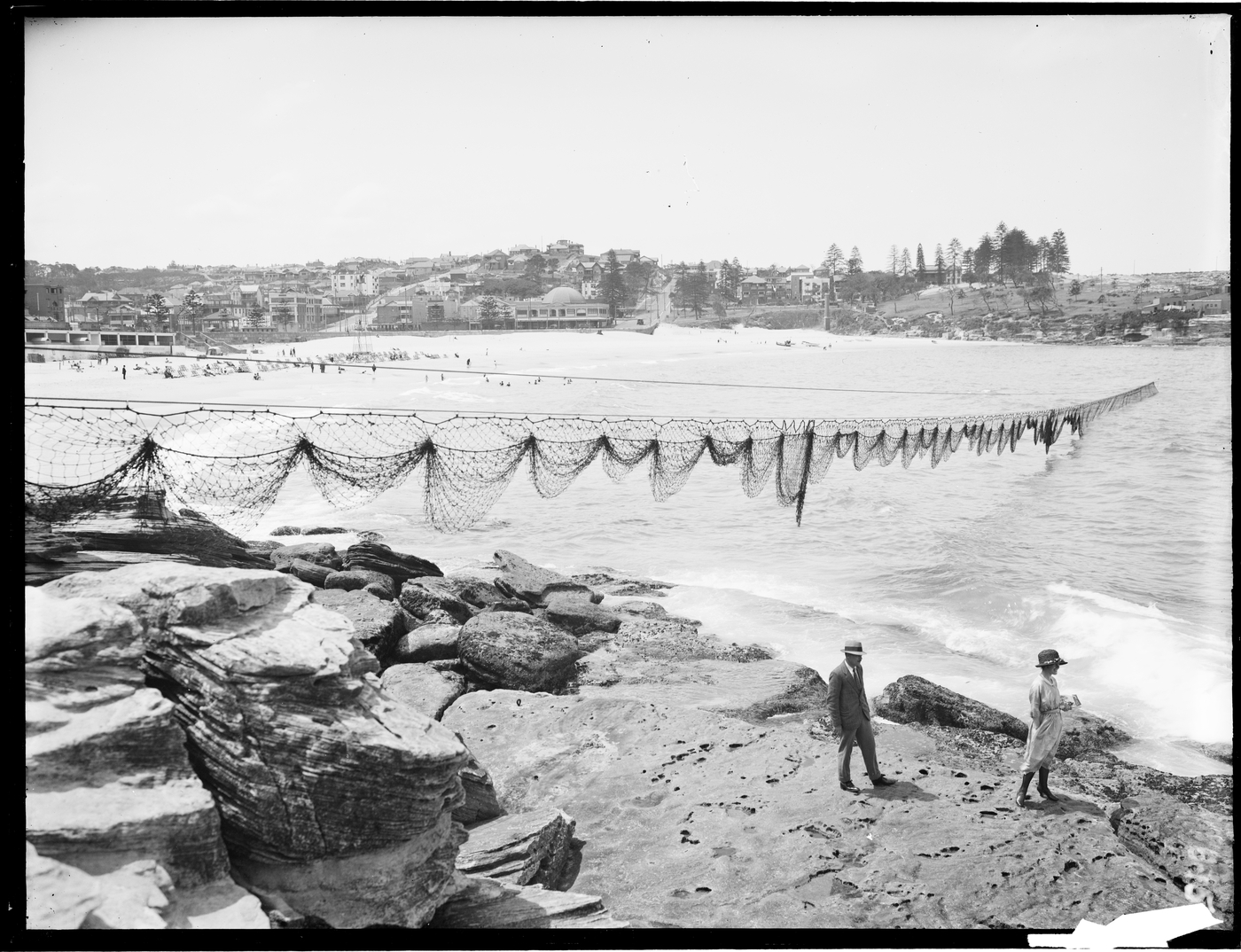

Coogee's shark net

[media]Of greater longevity than the pier was the shark net that was introduced at Coogee in November 1929. On its official opening the shark net attracted a crowd of 135,000 excited onlookers. The celebration was promoted as a 'Come to Coogee Week'. Within four months it was estimated that over 800,000 swimmers had swum in the protected waters of Coogee beach. [18] Indeed, the shark net, costing more than £6,500, was seen to be a revolutionary enterprise at the time and it received worldwide publicity. [19] [media]The erection of the shark net also led to the innovative introduction of night swimming and the one-penny admission fee ensured that Randwick Council was handsomely rewarded for extending the opening of the beach in the evenings. The net survived until World War II when it was removed for security purposes. [20]

Women-only swimming

Close to Coogee Beach, McIvers Baths were built in 1886. The McIver family ran the baths until 1922 when the Randwick Ladies Amateur Swimming Club was formed. The swimming club took over the lease and still hold it today. Since 1886 these baths have provided a place for only women to swim. From nuns to Muslim women remaining covered for religious or personal reasons, these baths have long held significance for many women, a fact recognised by the bath's listing on the New South Wales Heritage Register. [21] In 1995 a complaint was made to the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board by a male resident who was barred from using the baths because of his gender. However, the State Government granted the pool an exemption from the NSW Anti-Discrimination Act and today the baths remain open to women and children only; they are the last remaining women's only seawater baths in Australia.

[media]Close to the women's baths, Wylie's Baths were built in 1907 and they were open for mixed bathing between the hours of 6am and 10pm. Described by many swimmers as 'like swimming in a large rock pool' Wylie's Baths remain an enduring attraction of Coogee today. [22]

Heritage

By the 1920s and 1930s the 'villas' and terraced gardens that the Daily Telegraph had imagined in 1887 were starting to characterise Coogee, giving it an Art Deco feel. It remained a popular and fashionable resort but was now a place of both residence and recreation.

Despite its relatively slow development, Coogee has many heritage-listed houses built in the nineteenth century and other buildings including the Coogee Bay Hotel. Remarkably, the hotel was originally built to be a private school in the 1860s. After a second story was added to the building around 1875, the school became a hotel with a long and lively reputation. Today the Coogee Bay Hotel remains a popular spot with locals, tourists and weekend visitors alike; perhaps reflecting the historical nature of Coogee itself.

References

Ford, Caroline. Sydney Beaches: A History. Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2014.

Grellis, Alison and Peter Cowan. The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality: A Guide. Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990.

Lawrence, Joan and Alan Sharpe. Eds. Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs. Crows Nest: Kingsclear Books, 1999.

Pollon, Frances. The Book of Sydney Suburbs. Compiled by Frances Pollon; original manuscript by Gerald Healy. North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1988.

Randwick Municipal Council. Randwick: A Social History. Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985.

Notes

[1] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 120

[2] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 120

[3] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 120

[4] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 120

[5] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 71

[6] Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches: A History (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2014), 26

[7] Cited in Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 120–21

[8] Alison Grellis and Peter Cowan, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality: A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 41

[9] Cited in Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 77

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 May 1889

[11] Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches: A History (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2014), 35–36

[12] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 122–23

[13] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 130

[14] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 84

[15] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 84

[16] 'Abridged Prospectus, Coogee Ocean Pier Company, Limited,' Advertising, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1926, 12. Retrieved from Trove, 12 November, 2015, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16282099

[17] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 87

[18] Alison Grellis and Peter Cowan, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality: A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 43

[19] Randwick Municipal Council, Randwick: A Social History (Kensington NSW: University Press, NSW in association with Randwick Municipal Council, 1985), 89

[20] Alison Grellis and Peter Cowan, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality: A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 43

[21] Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches: A History (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2014), 282

[22] Joan Lawrence and Alan Sharpe, Pictorial History Eastern Suburbs (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1999), 132

.