The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Built environment

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Built environment

Sydney has grown in a particular way in response to its extraordinary location, geography, and cultural, political and economic history. [media]Like most cities it has established and adapted regulatory frameworks, urban forms and architectural traditions. Over time Sydney has developed its own kind of logic, which pervades its architectural, landscape and urban identity.

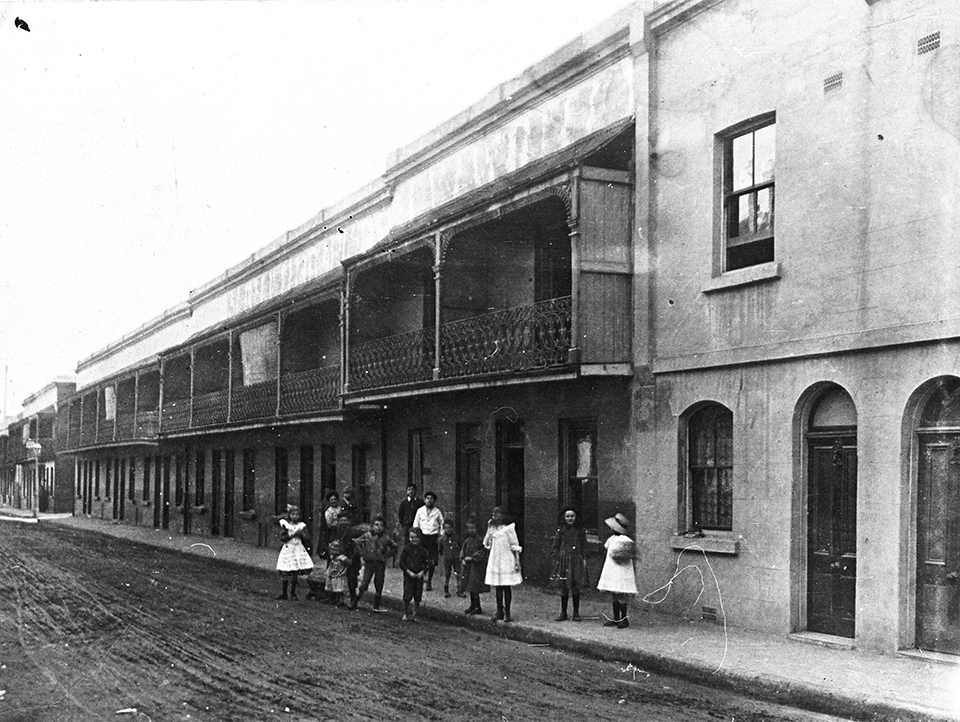

A number of significant urban projects have given various parts of the city distinct form and character. They fall into four major groupings: some are related to the generally public foreshore of the harbour and coastline; some are enduring and memorable layouts that are related to the geography of their sites and include streets and extensive parklands around watercourses, including those at Parramatta and Windsor; some are centred on public works and buildings of distinction, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Sydney Opera House and a collection of fine golden sandstone buildings; [media]and some are suburban subdivisions that support a diverse range of housing types including nineteenth-century terrace houses and some outstanding twentieth-century apartment buildings.

Sydney's beginnings

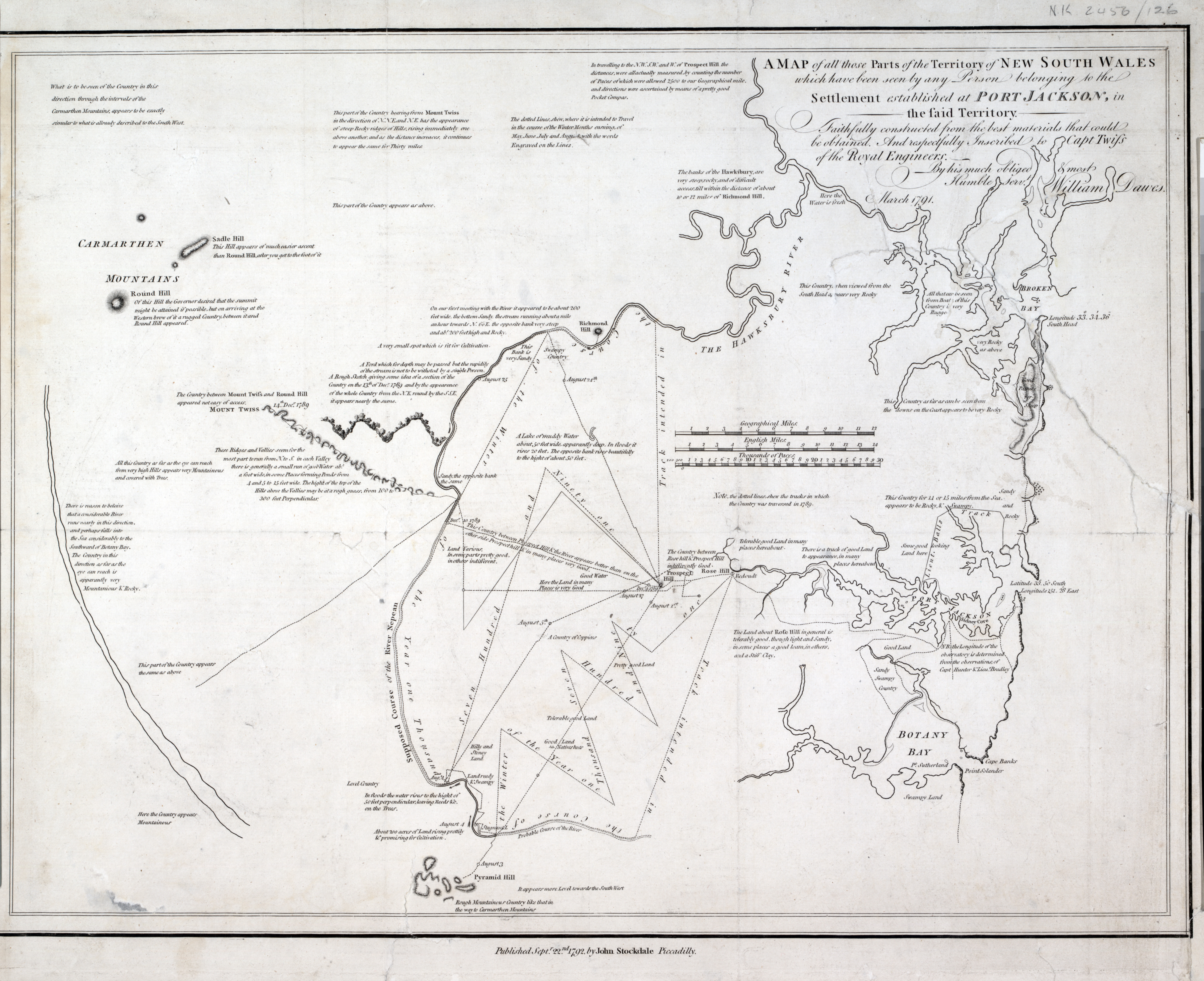

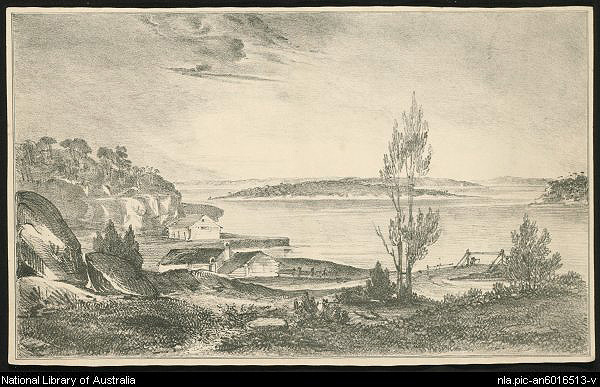

The foundation of Sydney in 1788 marked the beginning of the permanent European occupation of Australia and the dispossession of the people who had occupied the land for thousands of years. [media]Just as the harbour and the shelter of what became known as Sydney Cove attracted the founding English governor, Arthur Phillip, the harbour and its bays had been the place of intersection between the territories of three Aboriginal groups – the Cadigal, the Eora and the inland Dharug.

Aboriginal people had long exploited the natural assets of the Sydney basin, with its supplies of fresh water, fauna, bush tucker and the rich pickings of the tidal zone. Without building permanent dwellings, Aboriginal people nevertheless effectively occupied their territory. They moved on tracks along the sandstone ridge tops where the vegetation was sparse, allowing reconnaissance of the land. [media]Numerous shell middens and rock engraving sites marked their attraction to the foreshore and its permanent use and occupation. The English settlement took advantage of the Aboriginal tracks as a ready means of exploring the land, and exploited the middens as a source of lime for building.

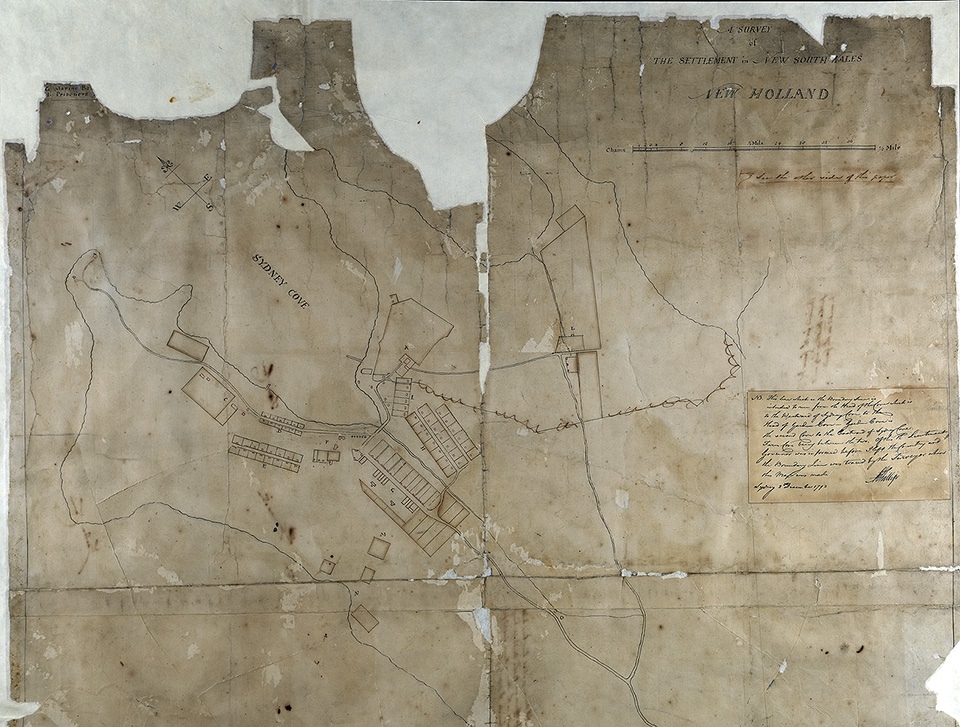

[media]Governor Phillip produced two foundation town plans – one at the point of embarkation at Sydney Cove in 1788, the other inland at Parramatta in 1789, at the point where the river turns to fresh water. The inspiration for Phillip's Sydney Town plan is sometimes assumed to be English architect Christopher Wren's Greenwich complex. However the Marquis de Pombal's reconstruction of Lisbon, Portugal following the earthquake of 1755 and Spain's 'Laws of the Indies' of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, governing colonial development, could also be influences.

Phillip's plans had a number of common elements including a main street about 200 feet (60.9 metres) wide, forming an axis between the waterfront and a hill top which accommodated the Governor's residence. Each street was lined with regular allotments. [media]At Sydney Cove, the plan also had a waterfront square and a quay front. The principal street was clearly aligned to catch the cooling summer sea breeze from the north-east and to allow prospect to the harbour. Cross streets were also indicated on both plans, although a coherent grid or town limits appear to have been absent. While the Sydney plan was pegged out, it was abandoned almost immediately for a more irregular and incremental settlement pattern aligned with the freshwater Tank Stream. The Parramatta plan, however, largely remains in place.

By the time of Governor Phillip's departure in 1792, the full extent of the Cumberland Plain had been explored. The Aboriginal tracks became the foundation of a major road system that remains in place today. Under Phillip, all lands had been reserved for the Crown, but upon Phillip's return to England a period of interim rule occurred, allowing military officers to grant themselves rural allotments across the territory. The grants were at key geographic points, on waterways or where good soil could support farms. Grants of 30 to 100 acres (12.1 to 40.4 hectares) were made in 1792–93 at various places including Concord, Prospect Hill, Newtown and Ryde. [1] [media]The earliest surviving house from this period is Elizabeth Farm, built at Rose Hill in 1793 for the ex-soldier John Macarthur.

Public buildings give form to the town

Lachlan Macquarie was Governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1821. During this time he initiated a series of public buildings that gave Sydney a distinctive form, elements of which persist today. Arriving in Sydney in 1814, the convicted forger Francis Greenway was soon enlisted by Macquarie to act as Civil Architect [2] for the majority of these buildings. [media]Along the town's eastern ridge Macquarie erected first a hospital, in the form of three elongated buildings aligned in a range, followed by Greenway's Government Stables to its north and Fort Macquarie further north on Bennelong Point. Between the stables and the fort a new Government House was proposed and later built.

[media]To the south of the hospital on the high ground Greenway set out a transverse line of three buildings – law court, church and convict barracks. The later two faced each other across a square at the head of the new Macquarie Street (set out in front of the earlier hospital) and addressed a proposed larger square to the south (now Hyde Park).

[media]On the western ridge, Dawes Point Battery was placed opposite Fort Macquarie, framing the promontories to Sydney Cove. Further south along this ridge stood the earlier Fort Phillip, the Military Hospital and a long range of military barrack buildings facing over the parade ground, where Wynyard Park now is.

[media]These buildings were built expediently, and often featured a bluff front or were narrow and elongated to give emphasis and importance to their presence. In height and scale they greatly exceeded the ordinary buildings of the colony and their placement on the key geographic features provided a civic order that dominated views of the fledgling town.

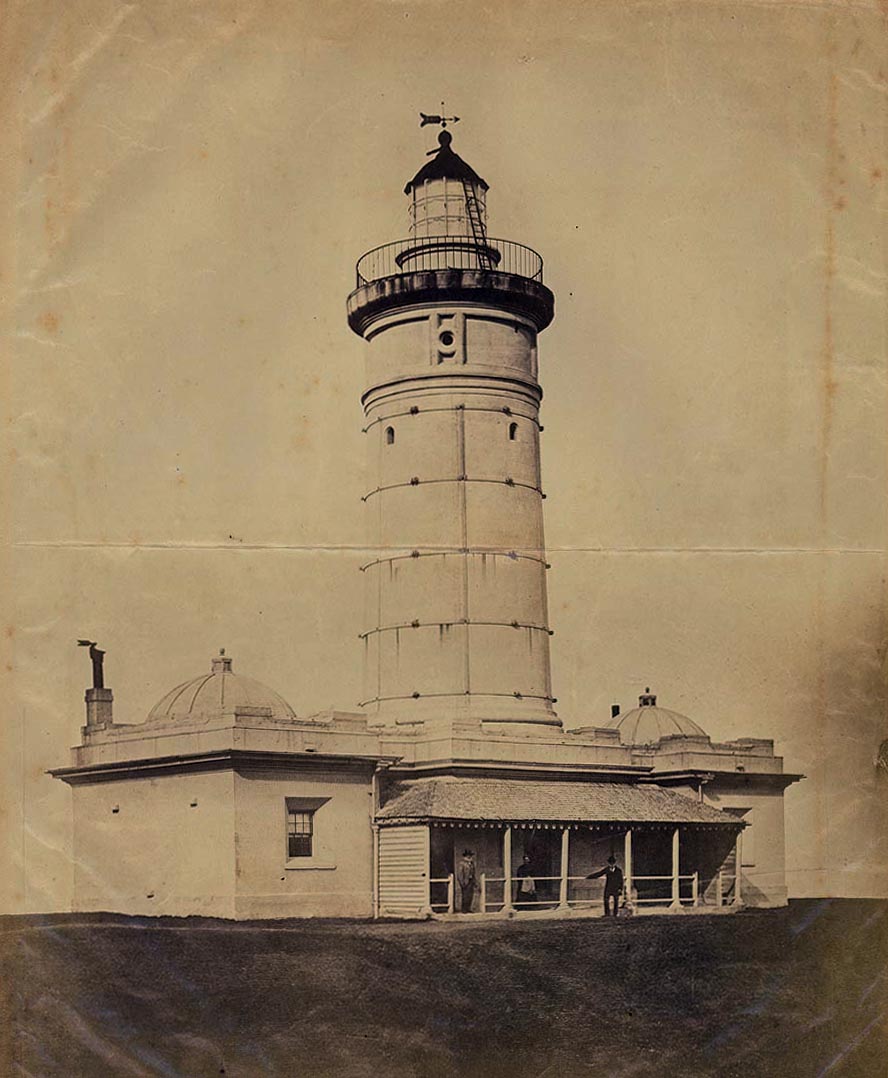

Outside the township, Macquarie set out works that continue to define the city limits. [media]Due east of the township at what is now Vaucluse, Greenway erected a lighthouse on the cliff top overlooking the sea. Still visible from the city today, it announces the presence of the city to incoming ships and declares the coastline to the city.

[media]At the edges of the Cumberland Plain, Macquarie laid out the new towns of Liverpool, Castlereagh, Richmond, Wilberforce, Pitt Town and Windsor. Located along the Nepean/Hawkesbury and Georges Rivers, these towns established the future limits of the metropolis. The edge of Sydney's outer suburbs has only recently reached these historic towns.

Rules for laying out towns

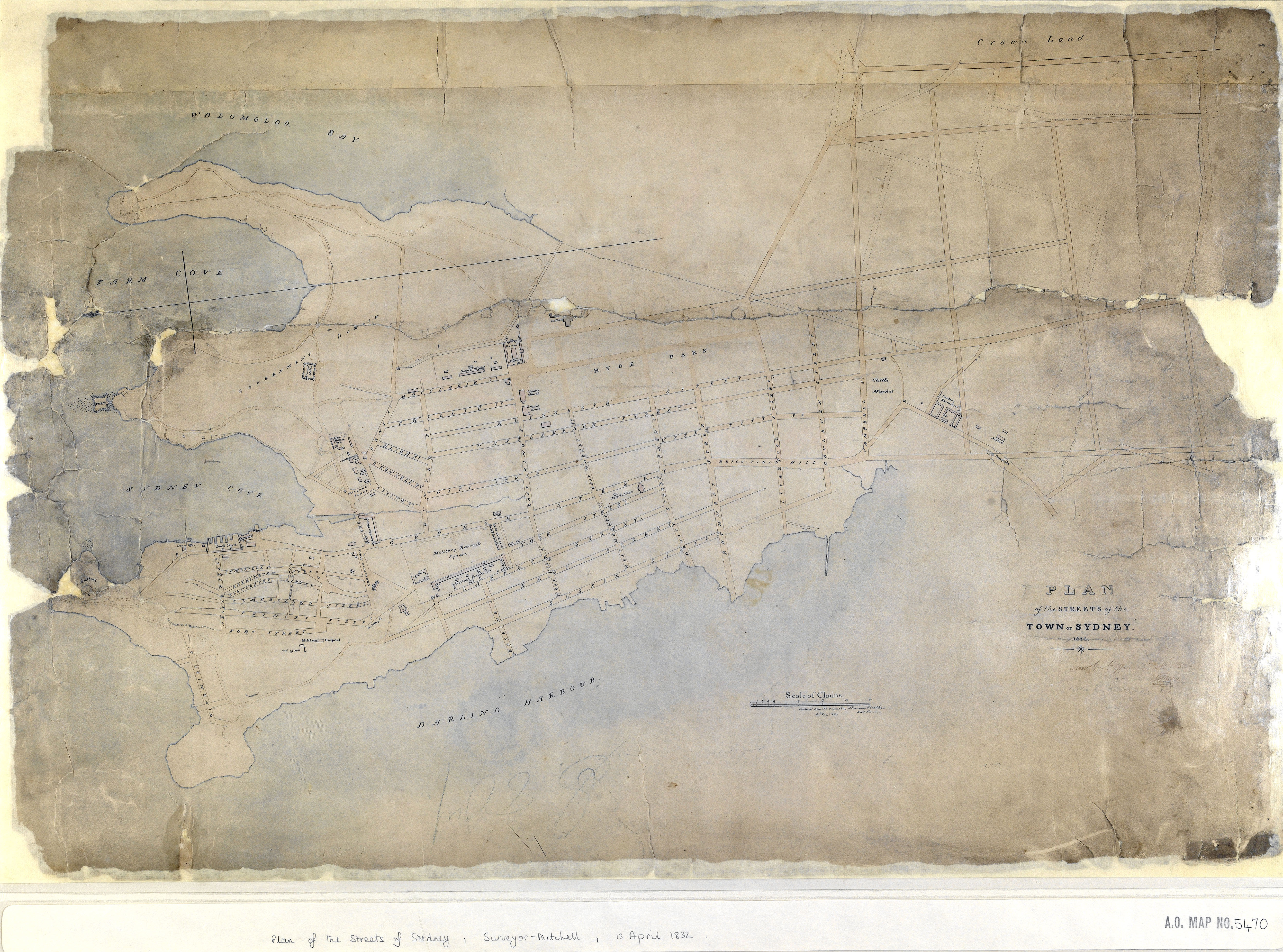

In 1824, the new governor, Darling, established a set of rules for laying out towns based on a grid of square blocks 10 chains (around 200 metres) on each side, separated by streets 100 feet (30.4 metres) wide. [3] Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell set about implementing a series of plans based on these rules but with narrower streets, generally one chain (20.3 metres) wide. [media]Mitchell also laid out the future suburbs of North Sydney, St Leonards and Coogee. These strict geometric rules were adapted to fit Sydney's varied topography and natural features such as foreshores and watercourses. Occasionally major geographic features were reserved as public land. This resulted in the prominent placement of public buildings and the beginnings of extensive park systems. Mitchell's large blocks provided a permanent but flexible framework for the future, allowing ongoing opportunities for the addition of a finer grain of streets, subdivision and substitution of denser building types.

[media]In 1828 Darling also introduced a 100-foot-wide (30.4-metre-wide) public foreshore reserve to land grants. Although parts of the New South Wales Crown Lands Alienation Act 1861 bypassed this measure, large areas of the harbour foreshore and coastline were kept in public ownership, preserving a focus on public rather than private use.

[media]In 1836, the first Colonial Engineer, George Barney, produced an ambitious scheme for regularising Sydney Cove. The project combined the dredging of the cove, reclamation of the Tank Stream where it broadened to meet the cove and the erection of a continuous stone quay wall. The Semi-circular Quay was constructed of sandstone quarried from associated works including nearby Argyle Street, which extended as a dramatic cut through the western ridge.

Sydney in this period developed into a compact and coherent Georgian town, with consistent streets lined with whitewashed buildings of regular proportions. The best surviving street from this era is Lower Fort Street in Dawes Point, which displays a coherent run of grand villas and paired houses.

In the 1840s, projects for filling large tracts of surplus land in and around the city were devised. [media]Such projects included the subdivision of the army barracks on the western ridge to form Wynyard Square, a park surrounded by terrace housing reminiscent of a London residential square; the extension of existing streets northward through the Government Domain to the new quay; and the new grid extensions of Darlinghurst and Surry Hills to the east and Redfern to the south.

Government architects establish Sydney's character

The successors to Francis Greenway played major roles in important urban developments in Sydney. [media]Mortimer Lewis, Government Architect between 1835 and 1849, designed a number of new institutions including the Darlinghurst Courthouse, the Australian Museum and Customs House. These were located at pivotal points in the city and built of golden Sydney sandstone. The severe character of Lewis's architecture was suited to the authoritarian society of the day.

[media]James Barnet, [4] who became Government Architect in 1862, set about overbuilding many of Lewis's works and creating a new series of major public buildings, including the General Post Office (GPO), Lands Department and Colonial Secretary's building. These richly modelled sandstone buildings covered whole city blocks and towered above the existing surrounds, creating a new scale and grandeur for Sydney. Barnet's grasp of the urban potential of his GPO building generated one of Sydney's finest streets, Martin Place, which was realised over the following 60 years. Across the expanding suburbs, Barnet constructed numerous fine public buildings such as post offices and courthouses.

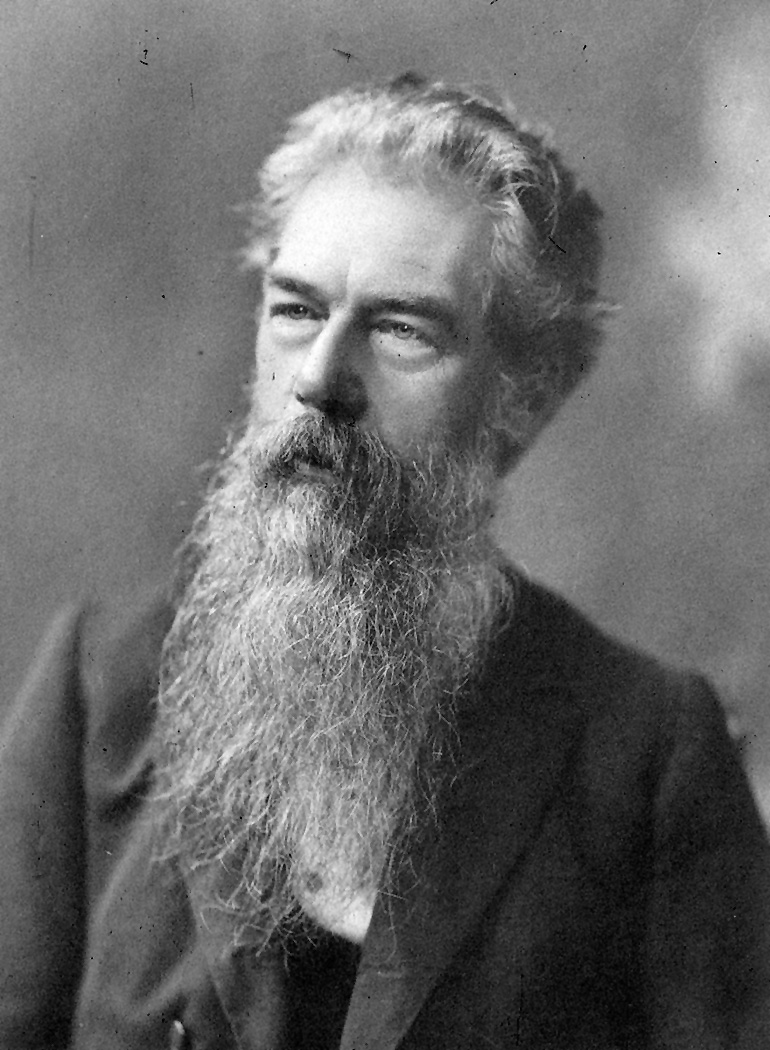

[media]Barnet was succeeded by another dominating figure, Walter Liberty Vernon, who was Government Architect from 1890 to 1911. In turn Vernon overbuilt many of Barnet's city buildings, including the General Post Office, Customs House and the Australian Museum. However, his own plans for major new city buildings were only partially realised, to be continued by others throughout the twentieth century. Vernon's public buildings, including many spread across the expanding suburban landscape, were generally more domestic in form and character than Barnet's.

Public transport and the growth of the suburbs

While Barnet and Vernon were defining Sydney's civic architecture, the inner suburbs mainly consisted of rows of speculative terrace houses on small lots. Clusters of shops and institutional buildings sprang up along transport routes, forming embryonic main streets. [media]In the 1880s the rapid expansion of new transport infrastructure allowed the urban area to extend beyond its established core, as a succession of railways, tramways and ferry wharves were built.

Each type of public transport created particular spatial relationships and configurations within the suburbs. [media]Railways encouraged the development of new suburban centres around each station at one- to two-kilometre intervals. Tramways saw the development of continuous linear main streets with minor concentrations at their stops, usually located at the crossroads of new estates. Ferries arrived at promontories or at the edge of bays, at wharves often connected by tram to new main streets running along the ridge tops overlooking the harbour.

In Australia, the word suburb means any neighbourhood outside the city centre. The English language lacks a range of terms to describe the relative densities of different areas of the city, such as the French quartier, faubourg and banlieu[media]. The inner-city suburbs in Sydney in the nineteenth century were generally quite intensively developed with small houses, with lot sizes typically ranging from 80 to 240 square metres.

By 1900 Sydney was transforming from a place of walking scale to a commuter city. Unlike the older suburbs of closely packed continuous terrace housing, new garden estates consisted of detached houses, underpinned by the transport investment. Eclipsing the terrace house, semi-detached dwellings, cottages and bungalows became the predominant housing types, laid out along new 66-foot-wide (20.4-metre-wide) suburban streets.

Sydney after 1900

Walter Liberty Vernon's period as New South Wales Government Architect coincided with an era of major urban reform. After a severe depression in the 1890s, a new optimism, sparked by the turn of the century and Federation of the colonies, ran until the outbreak of World War I.

New institutions were created to reform the city and its citizenry. [media]In 1900 an outbreak of the bubonic plague prompted the New South Wales government to resume the waterfront encircling the city centre and some adjoining areas. The Sydney Harbour Trust was formed to rebuild Sydney's chaotic wharfage, but by 1906 it was extending its charter to include the construction of a continuous port roadway, new residential streets, workers' housing, kindergartens and public houses.

Following the success of the early work of the Sydney Harbour Trust, other New South Wales government agencies, such as the Public Works Department and the newly formed Housing Board, embarked on slum clearance and ambitious reconstruction programs. [media]The resumed areas, focused on Millers Point and The Rocks, became a type of urban laboratory with the construction of new higher density forms of public housing, socially progressive public facilities and new warehouses. This new development was all carried out within a framework of remade street layouts and infrastructure improvements. Sydney City Council also became active in urban interventions during this period, as their City Architect, RH Broderick, realigned streets, rebuilt the city market district, and erected a number of compact mixed-use shop and apartment projects.

In 1908–09 the New South Wales government held a Royal Commission into the Improvement of the City of Sydney and its Suburbs.[media] Submissions were received by an array of experts, including architect John Sulman and engineer Norman Selfe. Public hearings considered a variety of proposals for large-scale urban reform along the lines of Haussmann's Paris and Burnham's Chicago.

Many of the commission's recommendations were soon commenced, including the widening of Oxford and William streets to 100 feet (30.4 metres) to create boulevards on the major eastern approaches to the city. New forms of mixed-use buildings with continuous facades were constructed fronting these boulevards, containing interconnected shops, warehouses, small factories and apartments at different levels. The underground city circle railway and further extensions to the tramways were also begun in earnest. The railway emerged at the quay front, offering the potential for a new front to the city, but the delayed completion of this project resulted in a lacklustre version of the bolder original intention.

As with other cities, the new town planning movement became a dominant force in Sydney's urban debate. As militant promoters of a low-density city of detached houses with gardens, urban reformers and many town planners attacked urban reform involving inner-city higher-density public housing. [media]Reacting to this pressure, the annual Parliamentary Reports of the Housing Board illustrated and promoted their new garden suburb at Daceyville, to the virtual exclusion of their greater production in The Rocks.

Public sector initiatives were mirrored in the private sector. [media]The apartment building, based on English and American models, was introduced in the city centre after 1900. Land speculators realised versions of the village green and the garden suburb at the Appian Way in Burwood, and at Haberfield.

The interwar period

The tram system reached its maximum extent in 1926, when the city boasted 190 miles (325 kilometres) of tramlines. Under the chief engineer JJC Bradfield, new and upgraded infrastructure acted as the strategic support for urban development. Main roads were upgraded, and new connections built. The train system continued to expand, and Bradfield implemented the electrification of the railways and oversaw the construction of the city underground loop.

[media]Bradfield's major legacy was the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, after 100 years of unrealised plans for a harbour crossing. Constructed between 1923 and 1932, the bridge connected the vast areas of the north shore to the city centre on the south side of the harbour, allowing residents to avoid ferries or a circuitous road journey. The bridge, however, was not simply a work of heroic engineering, as Bradfield took great care to integrate the structure's massive approaches with the fractured urban fabric caused by resumption and demolition. The bridge's symbolic and civic character was appropriately represented in the form, detail and material quality of its construction.

[media]The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge marked the end of the era in which public authorities took a leadership role in forming the city. The public authorities such as the Public Works Department, Sydney City Council and the Sydney Harbour Trust had been in retreat since World War I, initiating only modest projects or completing the vestiges of their incomplete major projects in a limited way.

Instead the dynamism shifted to the private sector. In the city centre, a new generation of buildings sprang up to the 150-foot (45.7-metre) height limit, which had been set in 1912, ostensibly constrained by the length of ladders on fire trucks. These buildings, accommodating offices, hotels, department stores, apartments and utilities, were usually framed structures with a stone or reconstituted facing. In the inner city and at beachside suburbs, new brick apartment buildings clustered. Neighbourhoods around Kings Cross had large concentrations of apartment buildings designed by architects including Emil Sodersten, Donald Thomas Esplin, John Mould and others. [media]Beachside suburbs such as Manly, Coogee and Bondi tended to have more standard builder-commissioned blocks of flats. Ranging between four and 10 storeys, they dramatically changed the scale and density of established suburbs.

Across the Cumberland Plain, suburbs continued to be rolled out along the tram and train lines. After World War I, construction of the formerly ubiquitous combination of tight urban blocks with lanes, small lots and terraced houses ceased completely. Instead, plain bungalows set on larger lots began populating the suburbs.

[media]Around 1920 Leslie Wilkinson became the first professor of architecture at the University of Sydney. He refocused the university campus with a series of new buildings and landscaped spaces, and built a wide range of houses, churches and apartment buildings. Through teaching and work he introduced students to the design principles of Mediterranean buildings well suited to Sydney's climate. The concern for climate suitability and the outdoor life continues to influence Sydney's architects.

Planning and suburbia after World War II

Sydney in the postwar period was dominated by the expansion of low density dormitory suburbs where residents depended increasingly on cars. While this process was not unusual in English-speaking countries, Sydney's expansion was marked by the acute failure of the various public authorities to productively shape this growth.

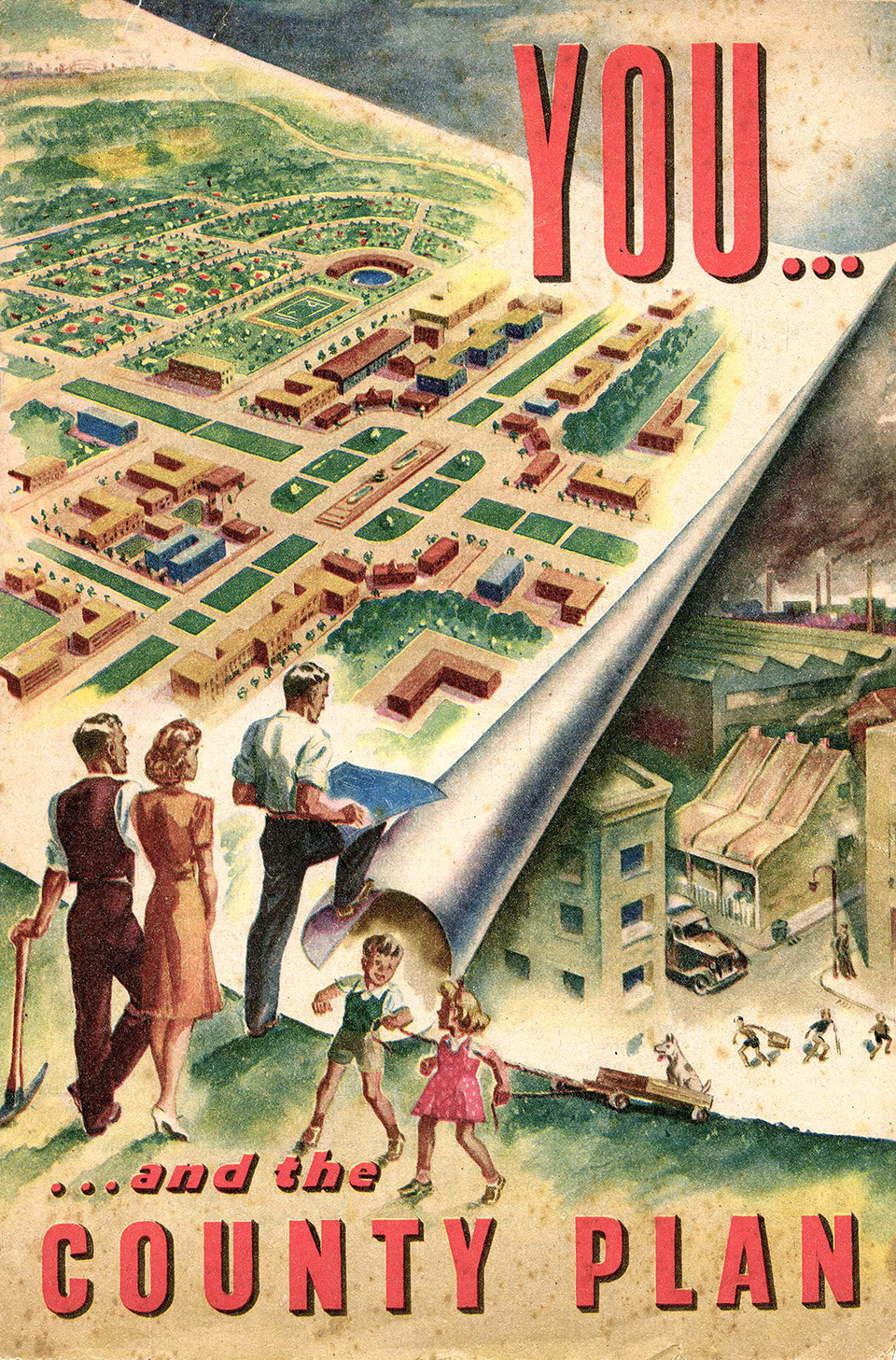

Certainly planning was attempted. Between 1945 and 1952, the County of Cumberland Plan was prepared as an ambitious physical plan to regulate the growth of the entire urban area. The result of 50 years of political agitation, the plan included the establishment of a central agency – the Cumberland County Council – Sydney's first attempt at metropolitan governance. However the County Council lacked an electoral constituency and immediately met a series of obstacles. The various local councils were less than supportive of a new central authority. The New South Wales government was sensitive to the threat of a potential political rival, and its various agencies and utilities went about their usual business in disregard of the County Council, effectively dismantling key aspects of the plan. For instance, the powerful New South Wales Department of Main Roads built most of the proposed major roads, whereas none of the planned railways advocated by the County Council were constructed. [media]The 1950s was also the era of Sydney's greatest economic folly – the total removal of the tram system and its supporting infrastructure.

Perhaps the greatest technical weakness of the County of Cumberland Plan was its over-reliance on regulation by zoning, rather than a program of urban projects. Zoning was meant to be the modern aspect of the plan but, with hindsight, it proved to be a failing. For example, the city's expansion was intended to be controlled by a green belt. The green belt generally consisted of rural areas that were zoned to prevent development, rather than designated as parkland. Naturally, landowners, angered by their loss of development potential, agitated to change the zoning. This was further exacerbated by state bodies such as the New South Wales Housing Commission buying up large tracts of green-belt-zoned land on the cheap for greenfield public housing estates. Although the green belt was intended to produce a more compact city, it had the opposite result as, little by little, the green belt was subsumed by urban development's outward push. [media]Zoning was also mono-functional, flattening out any remnants of the poly-functional urban projects of the 1908 Royal Commission into the Improvement of the City of Sydney and Its Suburbs.

Rather than projects of street widening that included public transport improvements and new building typologies, county roads were constructed with unusable residual frontages. Housing areas were zoned and therefore separated from employment and retail zones. This in turn caused a reduction in density and increased reliance on travel by private motor vehicles. Due to the lack of project-based actions or support of a range of building types, the County of Cumberland Plan contained few initiatives to intensify existing areas.

Modernism in the city

As postwar austerity gradually subsided, the 1950s saw the return of a range of public and private architectural commissions. The New South Wales Government Architect's Office, now a multidisciplinary bureaucracy rather than the architectural figurehead of the nineteenth century, re-emerged as a positive force, giving form to new institutions across suburbia. The New South Wales Housing Commission undertook a prolific program of construction of higher density inner-city housing and new suburban estates. Well-travelled local and émigré architects introduced international modernism in the construction of new apartment and institutional buildings. Best known of the immigrants was Harry Seidler, while Sydney Ancher, Arthur Baldwinson and others also sought to localise modernism.

Some fine apartment buildings were designed in higher density inner suburbs such as Kirribilli and Elizabeth Bay. Several such buildings were designed by Aaron Bolot, including Sydney's first cooperative housing project at 17 Wylde Street, Potts Point – a modern building with a curved front and strip windows predating similar buildings by Alvar Aalto in Europe.

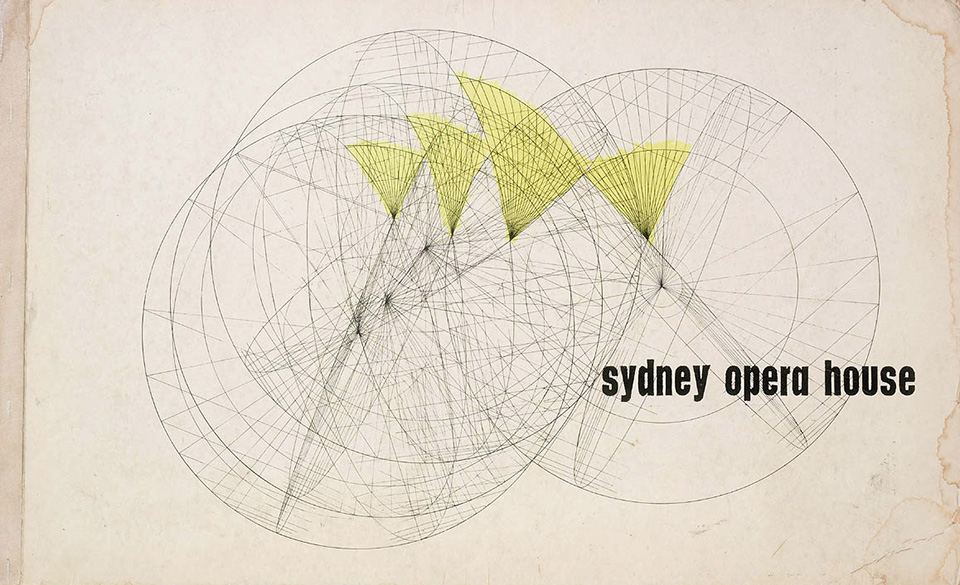

Commercial development in the city centre continued as in the interwar period, with sophisticated modern buildings seamlessly integrating Sydney's fractured geometry. [media]The Sydney Opera House competition in 1957, won by Joern Utzon's sublime masterpiece, started the process of reorienting the city towards its magnificent harbour.

The 1960s saw a significant increase in construction volume, and tensions grew about the changing form of the city. The 150-foot (45.7-metre) height limit was abolished, allowing the tower and plaza building types to commence their colonisation of the city centre, thus breaking with the continuity of the wall of street facades. [5] Of particular note in Sydney were the State Office Block group by the New South Wales Public Works Department, with Ken Woolley as project architect, and the Australia Square complex by Harry Seidler and Associates.

Public transport went into steep physical and political decline, due to the dominance of the motor vehicle and the intense lobbying of allied vested interests. The first motorway was constructed and many others were planned, leading to the devaluation and partial demolition of large tracts of inner-city suburbs. [media]In opposition, an unprecedented alliance of local residents and a trade union, the Builders Labourers Federation, led by Jack Mundey and Joe Owens, created the world's first 'green bans'. Union members refused to work on banned projects, making construction impossible and prompting compromises.

Land title reform allowed a new version of low-rise suburban flats in existing areas, built to minimal quantitative controls. The New South Wales Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961 gave rise to the pervasive housing type labelled 'the three storey walkup', which eschewed architectural or urban qualities. These regimented buildings were governed by setbacks on all sides, creating a detached building form usually set within an apron of concrete driveways with scant landscaping.

New fringe suburban estates were the norm, featuring detached houses on disconnected curvilinear layouts, while the later New South Wales Housing Commission estates progressively introduced ill-conceived variants of Stein and Wright's Radburn model. In this context, more progressive architects, including Bruce Rickard, Ken Woolley and John James, generally retreated to designing detached houses on rugged bushland sites. Some, such as Don Gazzard and Terry Dorrough, also had success in designing standardised modular housing, which later devolved into the project home industry.

Sydney's great architectural tragedy unfolded in 1966, when Joern Utzon was ousted before the completion of the Sydney Opera House by a new Liberal state government, who instead appointed a team of functionaries to degrade Sydney's one great work of twentieth-century architecture. This story is the topic of numerous books, pamphlets, lectures and even an opera. [media]In 2006 Utzon was finally invited to repair and renew parts of the building in association with the award-winning architect Richard Johnson.

The 1960s saw renewed attempts by the County of Cumberland planners to shape metropolitan expansion. The Sydney Regional Outline Plan was produced in 1968, opening the way for semi-autonomous satellite suburbs on transport corridors. The resulting development towards Penrith in the west and Campbelltown in the south-west exploded the extent of Sydney's reach, as these areas were at the edge of the Cumberland Plain, some 50 to 60 kilometres distant from the city centre. Instead of relying on zoning to produce a green belt, the plan outlined the ambitious acquisition of more than 1,000 hectares of land on the city's western fringe to act as a more effective impediment to continued sprawl.

The retreat of planning

Despite the establishment of the State Planning Authority during the 1960s, by the mid-1970s urban planners increasingly gave the impression that metropolitan planning was a futile exercise. Lack of cooperation between government utilities provided no mechanism to implement plans, while development interests acted aggressively against restrictions of their proprietary 'rights'. Sydney's political masters consistently favoured expediency over any long-term commitment to planning. Instead of reconsidering their methods, the planning profession retreated further from the making of projects (except on the grandiose scale of occasional new towns that remain as fragments on the outskirts of the most distant suburbs) contenting itself instead with process, regulation and development facilitation. The New South Wales Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 entrenched the planning profession and codified bureaucratic procedures. The act also introduced public participation in the making of planning instruments, which sometimes had the counter effect of validating and enshrining localised conservative values.

[media]In fumbling retreat, planning at the metropolitan scale became an exercise in non-determinism. The titles of successive state planning publications betray this lack of conviction and abandonment of action – Sydney into its Third Century [6] in 1988, Cities for the 21st Century [7] in 1995, and Shaping our Cities [8] in 1998. The progression of these titles shows that the first casualty was planning as the objective, then Sydney as the subject place. This is followed by the abandonment of any time scale, then finally the loss of all sense of the purpose of the publication. The documents proclaim generic vision, but lack any specific means of spatial, economic or temporal translation into action. They share an aversion to public transport provision and targeted improvements to existing areas, instead favouring ongoing low-density sprawl at the fringe.

During this period, Sydney proved its lack of commitment to real planning by reneging on a succession of new airport sites, despite the acute environmental and logistical problems caused by the inner-city location of the existing airport. In 2006 Sydney was once again toying with a 'metropolitan strategy'.

The return of the urban project

Without the leadership of effective planning, Sydney dabbled with government-controlled development corporations for public projects. The Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority and the Darling Harbour Authority both attempted to achieve tabula rasa in historic waterfront areas bounding the city centre. The redevelopment authority was prevented in its attempts by resident action and the green bans during the 1960s and 1970s. [9]

As the value of such parts of the city was increasingly appreciated during this period, the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority dropped the 'Redevelopment' from its name and set about a more considered series of interventions. During the late 1980s and 1990s, The Rocks became an artificial but charming tourist mecca, redolent with re-created tales of old Sydney and a showcase of considered conservation practices.

Darling Harbour was brazenly different. Created by the Darling Harbour Authority Act 1984, the authority's charter was to deliver a new tourist and entertainment precinct in place of the old wharves and goods yards that lined the western shores of the city centre, all in time for the 1988 bicentenary of European settlement. [media]The project was rushed, poorly conceived, and dominated by large works of little architectural quality. [10] Darling Harbour remains a place apart, lacking all integration with the space or daily life of the city surrounding it.

However the bicentenary also allowed some more considered interventions. In the civic heart of the city at Circular Quay and along Macquarie Street, the New South Wales Government Architect set about systematic improvements. [11] Free of the bombast of Darling Harbour, these sensitive urban projects were properly researched, coordinated and implemented. Although many elements at Circular Quay have already been replaced, the project set in train a better appreciation of the essential role of the public domain.

Since the 1990s, the dominance of abstracted statutory planning has been challenged by a series of new urban projects aiming to consolidate discrete parts of the city, combining architecture, landscape design and public art to create new compact urban places. [media]The former industrial areas of Ultimo/Pyrmont and Victoria Park/Green Square are being renewed with a series of projects that include new street layouts, public spaces and urban housing. In the lead up to the 2000 Olympic Games, the City of Sydney instigated a coordinated program of improvements of streets and squares throughout the city centre, which continues today in a program of renewed major parks and public buildings.

The construction of Sydney Olympic Park, instigated by a workshop led by Lawrence Nield, attempted the implementation of a grand urban plan. [media]A major railway station by HASSELL became its centrepiece, while the Tennis Centre by Bligh Voller Nield terminated the central boulevard.

At Parramatta, infrastructure improvements and public works are revitalising one of Australia's most historic urban centres.

At the University of New South Wales, the implementation of recent master plans and construction of associated buildings are transforming what was formerly a dour institutional campus into a web of memorable spaces.

[media]New models of suburbia, housing and town centres are being tested further afield, including at Nelsons Ridge and Rouse Hill. However tensions remain concerning the development of major sites while new public transport projects, such as a new tram system and the necessary expansion of the railways, are proceeding too slowly.

When taken together, a new urban form for Sydney can be anticipated. The better projects are based on the return of the street, integrating new infrastructure, supporting housing of increased density and design quality, introducing a mix of uses and redefining parklands that incorporate initiatives in water management and biodiversity.

The challenge today is the making of our cities, towns and suburbs as rich and engaging urban projects. Transcending the status quo of politics, statutory planning and the development industry, the urban project must meet the challenge of accommodating city communities in places that are legibly structured, properly related to infrastructure, environmentally responsive and adaptable in the long term. These projects must contain a sustainable mix of uses, an integrated implementation program, and appropriate environmental initiatives and take the role of generative models for the making of the city.

Beyond the failures of planning and the limits of architecture, urban projects hold the promise of continuing to revitalise Sydney.

References

C Faro and G Wotherspoon, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

P Emmett, Sydney: metropolis, suburb, harbour, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, Sydney, 2000

R Freestone, Model Communities: The Garden City Movement in Australia, Thomas Nelson, Sydney, 1989

Françoise Fromonot and Christopher Thompson, Sydney: History of a Landscape, Vilo Publishing, Paris, 2000

Chris Johnson, Shaping Sydney: Public Architecture and Civic Decorum, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1999

M Kelly, Faces of the Street, Doak Press, Sydney, 1982

Jennifer Taylor (ed), Tall Buildings. Australian Buildings Going Up: 1945–70, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2001

GP Webber (ed), The Design of Sydney: Three Decades of Change in the City Centre, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1988

Notes

[1] Unpublished architecture student research, University of Technology, Sydney, 1999–2006

[2] Chris Johnson, Shaping Sydney: Public Architecture and Civic Decorum, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1999

[3] Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 12 part 5, 1926

[4] Chris Johnson, Peter Kohane and Patrick Bingham-Hall, James Barnet: The Universal Values of Civic Existence, Pesaro Publishing, Balmain NSW, 2000

[5] Jennifer Taylor (ed), Tall Buildings. Australian Buildings Going Up: 1945–70, Craftsman House, Sydney, 2001

[6] New South Wales Department of Environment and Planning, Sydney Into Its Third Century: Metropolitan Strategy for the Sydney Region, the department, Sydney, 1988

[7] New South Wales Department of Planning, Cities for the 21st Century: In Brief, the department, Sydney, 1995

[8] New South Wales Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, Shaping Our Cities: The planning strategy for the greater metropolitan region of Sydney, Newcastle, Wollongong and the Central Coast, the department, Sydney, 1998

[9] Kate Blackmore, 'A Good Idea at the Time: The Redevelopment of The Rocks' in GP Webber (ed), The Design of Sydney: Three Decades of Change in the City Centre, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1988

[10] Françoise Fromonot and Christopher Thompson, Sydney: History of a Landscape, Vilo Publishing, Paris, 2000

[11] Andrew Andersons, 'Circular Quay: The Image of the City' in GP Webber (ed), The Design Of Sydney: Three Decades Of Change in the City Centre, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1988

.