The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Women of Pitt Street 1858

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Women of Pitt Street 1858

[media]This 'virtual walk' down Pitt Street in 1858 seeks to uncover women who were engaged in earning a living in ways other than the much-recognised female occupation of domestic service. Women's contribution to the colonial economy has been increasingly documented over the last few decades, although most studies have focused either on the early convict era or on the period after 1870, when factory and office work opened up for women, educational opportunities expanded for them, and, in the 1890s, Australasian women were the first in the world to obtain the vote. [1]

[media]In mid-nineteenth-century history, colonial women were apparently valued for their reproductive rather than productive qualities, [2] and their contributions to the economy or as 'workers' were mostly seen as domestic servants (if working-class and single) or as 'colonial helpmeets', assisting their husbands, fathers and brothers, who were the real pioneers, businessmen and entrepreneurs. However, recent work has started to question this idea of a domesticated female population, unemployed other than as domestic servants, [3] with studies uncovering teachers, publicans, farm workers [4] and postmistresses. [5] Indeed, census figures for Sydney for 1861 reveal that, of the 40 per cent of the adult female population who actually declared an occupation, only half of these were domestic servants, leaving 20 per cent of the adult female population with alternative occupations. [6] In this group, there were a range of women who were engaged in small businesses of their own rather than employed by others.

Until the last few years, available sources meant that tracking individual women over long periods was difficult, if not impossible. [7] Today we have the distinct advantage of online, searchable indexes from archives around the world, as well as the very recent, searchable, online databases from the newspaper digitisation projects in both New Zealand and Australia. [8] These resources have revolutionised research. What once would have required months of painstakingly scrolling through pages and pages of microfilmed newspapers searching for names, now takes far less time and is far more foolproof. As a result, it is now possible to argue more strongly that many women were engaged in productive labour in Sydney in the mid-nineteenth century, even though women were legally, politically, educationally and economically disadvantaged, and the Victorian ideal of domesticity was rampant in the colonies, dictating that women should be in the 'private sphere'.

This ideal of domesticity was both middle-class and an ideal – for many women from lower down the social scale it was neither relevant nor practical. For the majority of urban colonial women, attitudes towards women's work tended to reflect working-class pragmatism rather than middle-class domesticity. Women worked as employees or as small businesswomen, alongside family members or independently, usually from necessity and within a distinct range of occupations. Although these women have become almost invisible in the historical record and although contemporary diaries and letters generally fail to mention them, they were nevertheless present and visible to their fellow settlers. [9]

A 'virtual walk' down Pitt Street

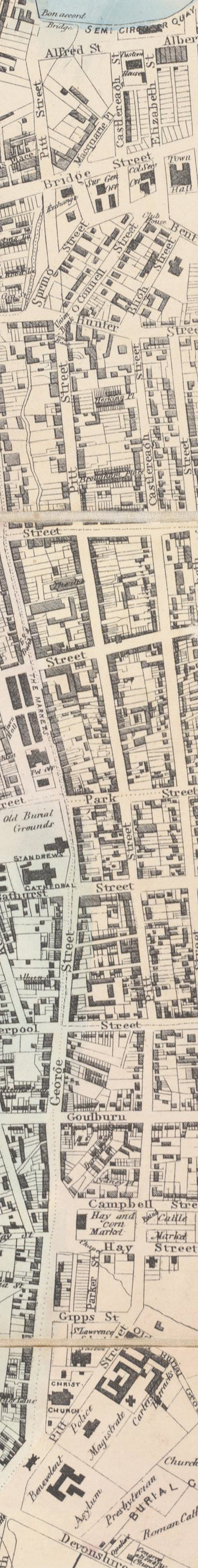

By taking a 'virtual walk' along seven blocks of Pitt Street in Sydney in 1858, it is possible to get a real impression of how many women were present as property owners, independent householders, employers and employees, and to illuminate the activities in which they were engaged. Pitt Street was and still is a main street in Sydney, and 1858 is a year well-served by sources. (It is also, unfortunately, the year that the street numbers in Pitt Street were reversed, making the task of establishing continuity of residence somewhat more convoluted, although not impossible).

This 'virtual walk' also shows the ways in which women's lives are obscured in the sources. Investigations into each woman with a connection to a Pitt Street property in 1858 involved taking names found in the trade directories and rates assessment books and following each name though newspapers and births, deaths and marriages records, passenger lists, probate and insolvency records as well as similar British sources. [10] Some women's lives have been relatively easy to uncover, back into the past, through marriages, emigration and life in England, and forward into the future, to childbirth, widowhood, remarriage and death, while others remain elusive. Sometimes it is impossible even to find these women's first names, or to positively identify them among others with the same name.

A glance at the trade directories for 1857 and 1859 produces 34 women listed in 1857 and only 23 in 1859. This is in addition to 341 listings for men in 1857 and 299 men in 1859. In the 1858 rates assessment book, there are 30 female householders listed and 370 men. Some of the difference here is the result of the renumbering and also the inclusion, or not, of properties 'off Pitt Street'. None of these figures would inspire confidence when looking for a female presence in Pitt Street. However, taking this 'virtual walk' down the street in 1858, and peeking in the windows of the shops and houses to investigate more closely, highlights a far larger presence of women in one of Sydney's principal streets. It also provides a snapshot of the variety of experiences of colonial women.

Although concentrated in a small range of types of employment, there are widows, wives and spinsters, some working alone, some with husbands, and others in partnerships with other women. Some women have reinvented themselves upon emigration or out of necessity after being widowed, while others had experience running businesses in England. The significance of family support is evident, as is the way in which families became interconnected with other families in the same line of business. Publicans' daughters married publicans and became publicans themselves, for example.

The walk starts on the corner of Hunter and Pitt streets outside the Union Bank and follows Pitt Street south to where it meets George Street.

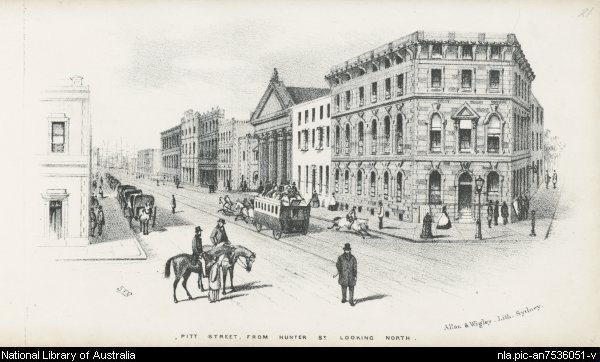

Block One: Hunter Street to King Street

[media]Turning left out of Hunter Street and heading south past the Union Bank towards King Street, there is the house of Ellen Codlin. A poulterer, Elizabeth Knight, who lived next door after her husband died in January 1855, leaving her pregnant with three young children, has moved on since her remarriage late last year. [11] Similarly there is no sign of the washerwoman, Mrs Morris, who was living in the next house. [12] A few houses down lives Maryann Mop. [13] One can pause to admire the fruit at Mrs Ann Makin's shop, [14] and then glance at the blank windows of what was Madame de Lolle's millinery business, 'Maison Francaise'. She is now in George Street since the very public split last year between her and the French teacher, Emile de Lolle, who went so far as to advertise that he would no longer be responsible for the debts of the person 'calling herself Madame de Lolle which name she is not entitled to bear'. [15]

On the other side of Brougham Place, Susan Glue and her husband, John, are busy at their labour registry and coffee house. [16] Susan married John in 1854 and has taken charge of the female servant part of the registry office which she will do until 1862. After the birth of her fourth child, she will open in Ashfield an 'Establishment for Health', essentially a boarding house, while her husband supervises the (now a grocery) shop in Pitt Street. She will die in 1866. Her husband will quickly employ Miss Mary Bourne to oversee the boarding house, marrying her within a few weeks. Recently the Glues have had some new competition for their registry office; Marianne Pawsey has just moved her own Servants' Registry Office almost next door. Pawsey has been running her business on her own since her husband's death in 1855, and the business has been in existence since 1848, when James Pawsey married the newly widowed Marianne Watson. Mrs Pawsey will remain in business in Pitt Street until 1872 when she will pass the registry office to another woman, Charlotte Wilson, proprietress, with her husband, of Robinson's Ladies Baths at the Domain. [17]

Pawsey's landlady in 1858 is Rosetta Terry, who owns 37 of the 86 properties in this block. She is the widow of the very wealthy Samuel Terry, but these properties were hers before she married him, as she was a successful businesswoman in her own right. Terry herself lives on the west side of the street and another of her tenants is Madame Laroche, a milliner. Laroche has only just arrived in Pitt Street and will lose everything in a fire in 1859. She will resume business in the Market Buildings in George Street, where she will remain, variously and somewhat confusingly known as Jane, Annie and Victorine Laroche, for the next eight years. [18] It is possible that 'Madame La Roche' is the estranged wife of William Roche and began life as Jane Boyle, daughter of Sydney builder, John, and apprenticed to Mrs Canavan, milliner and dressmaker. [19]

Matilda Cox also lives in this first block of Pitt Street, selling the 'finest and best fruit' in Sydney. [20] Like Madame Laroche, she is also a new arrival and will move on to George Street in 1859. [21] Finally, on this side of the street is Eliza Hudson's music shop. For the nine years before George Hudson's death in 1854 and even after his death, in the 1857 Directory, this business was in his name, but Eliza has always had a main role. When the Hudsons were in partnership with John Gibbs, another Sydney musician in 1850, it was not George's but Eliza's name on the partnership agreement. [22]

Block Two: King Street to Market Street

[media]This next is the most fashionable block in Pitt Street, with 54 properties spread over the two sides of the street. Rosetta Terry owns the pub on the corner and the shop next to it, Miss Plowright owns the pub at the other end of the street, while Mrs Roberts owns three shops in between. One might stop for a drink on the western corner of King and Pitt streets in the Liverpool Arms, where Emma Palmer is interviewing prospective barmaids, assisting her husband, Benjamin, the licensee, while caring for her three small daughters and heavily pregnant with a son. [23] Alternatively one could drop into Harriet Rubsamen's hotel, the Elephant and Castle, on the eastern corner. [24] She moved here recently from her previous hotel in Castlereagh Street after her husband's death. When she remarries at the end of the year she will transfer the license to her new husband, William Camb, as is expected, but it is likely that she will continue to take an active part in the hotel. Or one could buy an apple from Mrs White's fruit shop. Although the shop is listed as Charles White's business in the directory, Mrs White has a role to play, advertising for female shop assistants, [25] a role that has increased since Charley White has recently extended his business to include an oyster saloon around the corner in King Street. [26]

Just down the street, one of Mrs Roberts's tenants is the infamous Caroline Pope. Her business is not listed in any trade directory but her profession is well-known. She was recently up before the courts for assaulting one of her neighbours. Julia Stevens, the wife of a sailor, also living somewhere in Pitt Street, had either been innocently fetching her daughter from the street or had been verbally attacking Pope, calling her a 'street-walking faggot', when Pope assaulted her with a decanter and possibly also bit her. [27] In a few months time, brothel keeper Pope will marry Richard Cochrane, also known as 'Dick the Cabman'. This will not improve her situation. She will attempt suicide in August 1859 and Richard Cochrane will be imprisoned for three months for beating her in October of the same year. By 1861 the couple will have separated, each declaring themselves not responsible for the other's debts. [28] Caroline Cochrane or Pope will remain in Pitt Street at the oyster saloon they have been running for two years, while Dick the Cabman will resume his old trade and colourful activities. [29]

Passing by Timothie Cheval's confectioner's shop, one might be reminded of the case in July 1856, when his manager, Miss Bohen, successfully sued him for her outstanding wages. [30] One can then stop for refreshment at the Prince Albert Restaurant. The proprietor, Thomas Jones, died in July last year, leaving his widow, Jane, with five children. She carried on the business successfully for several months, in spite of being assaulted by her Chinese servant in October 1857, [31] before marrying Robert Horne in February 1858, from which time his name has appeared in the trade directories. He will be insolvent in 1861, and again in 1882 after his wife's death in 1881. The business will be popularly known as 'Mother Horne's' during the 1860s and 1870s, which acknowledges to whom it really belonged. [32]

On the other side of the street is the Royal Victoria Theatre, where several actresses and singers are preparing for their performances. Just last year there was great excitement when Anna Bishop performed, [33] although at present it is just the regular company on stage, including Theodosia Guerin, who has been performing on Australian stages since the 1840s and will continue to do so for several years. Her life epitomises that of women involved in the theatre, full of transnational mobility and on the edge of respectability. She first appeared on stage as part of the company of theatrical entrepreneur, Mrs Anna Clarke, in Hobart in 1842, calling herself Mrs Stirling. She arrived in Sydney in July 1845, with, it would appear, a daughter. She married her fellow actor, James Guerin in 1846, using the surname Macintosh, had three children and then, after Guerin's death in 1856, married Richard Stewart in 1857. The register recorded his name as Gzech, and when their daughter is born in 1859 her surname will be recorded as Towsey. In spite of her last marriage, Theodosia will continue to use the name Guerin on stage well into the 1870s. Nevertheless, after her death in 1904 at the age of 90, she will be remembered primarily for her reproductive qualities, rather than for her work, as the mother of the much more famous Nellie Stewart. [34]

Eighteen of the businesses in this block are drapery and clothing stores, predominantly owned by men, but all reliant on female labour. [35] One can see lots of young apprentice milliners, bonnet makers and dressmakers, as well as the slightly more experienced 'first hands' and others who serve behind the counter, heading into Robinson and Morey's, Samuel Clark's and William Robson's establishments, to name but a few. Mrs William Robson, the real milliner of 'William Robson's' millinery business, will be busy as usual superintending the improvers and apprentices.

Closer inspection of the drapery business listed merely as 'Doak and Kerr' in the 1857 Directory reveals that it is run by Margaret Doak and her sister, Rebecca Kerr. It has been in existence since 1840 when Doak and her husband went into partnership with Kerr, shortly after they arrived in New South Wales. In fact the business is older than that, as Margaret Doak had her own millinery and dressmaking shop alongside her husband's carpentry workshop in Londonderry, Ireland, in the 1830s. [36] Anthony Doak died in 1857 and by the early 1860s Kerr will officially retire from the partnership. Doak will continue alone until, aged nearly 70, she will be joined by her married daughter, Minnie Beattie, in the 1870s. [37] Doak and Kerr will die within a few months of each other, both in their eighties and still both living on the business premises. [38]

Across the street from Doak and Kerr is Webb and Co, a millinery establishment run by Mary Webb, who has recently moved here from King Street, where she ran her business with another Mrs Webb. Mary Webb has been in business since at least 1855 and will still be in Pitt Street upon her death in 1867, when her death notice will record that she is 'late of Oxford Street, London'. [39] There are several Mrs Webbs and Mary Webbs in Sydney at this time, most of them dressmakers, and it has been impossible to identify Mary Webb of Webb and Co among them. It even caused confusion at the time. In February 1857 Mary Webb ran the following advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald:

Mrs Webb, London and Straw Hat manufactory, 41 King Street, begs to inform the public she has no connection with Mrs Webb, late of Castlereagh and Pitt Streets. [40]

After Mary Webb's death in 1867, her store will be absorbed into the neighbouring business of Emily Way, who is at this time still in Essex, England. She will emigrate in 1859 with her parents, marrying Ebenezer Way in 1864 and opening her business the year after. Mrs Way's business will do well, lasting until at least the 1950s as E Way and Co, and allowing Emily and Ebenezer Way to retire to Devon and leave an estate of nearly £30,000. However, at the firm's jubilee in 1914, Ebenezer Way and the firm's 'first manager, Mr B Boston...brother-in-law of the founder' will be celebrated, with no mention of Emily Way's contribution to the business. [41]

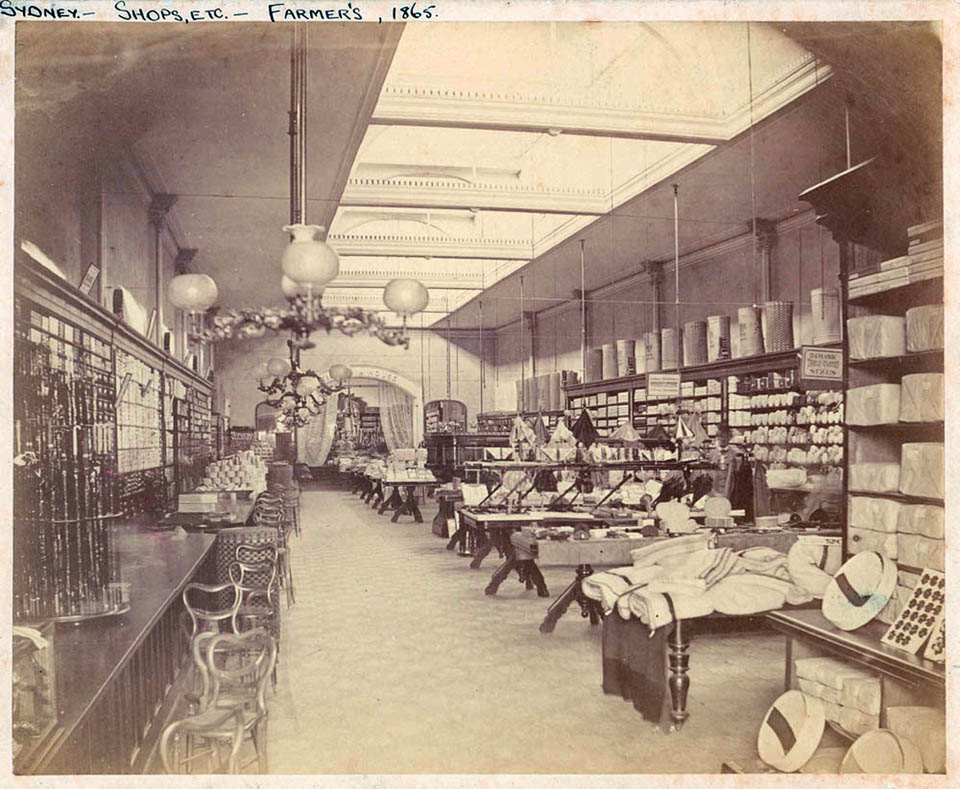

In a [media]similar story, Caroline Farmer started a millinery business in 1839, which has by 1858 become Farmer, Williams and Giles, on the same side of Pitt Street as Mary Webb's millinery shop. Her pivotal role will be glossed over in the Sydney Morning Herald's article about the 'Romance of Farmer's' upon its 'centenary' in 1940. It will note only that Farmer's wife had 'helped behind the counter'. [42] Next to Farmer's is another drapery shop, run by George Tuting, who had a drapery shop in Beverley in Yorkshire. He arrived in Sydney in 1850 with his second wife and five children under ten. His new wife is 47-year-old Mary Farmer, sister-in-law of Caroline, and in spite of her many stepchildren, she is also active in the family business, advertising for milliners and superintending the female staff, which also includes saleswomen. [43]

Having reached the other end of the block, on the west corner of Pitt Street is the Bull and Mouth, owned by Miss Plowright. It is run by Joseph Wakely, whose wife, Ann, is standing outside. She is well-used to the hotel business: her first husband was a publican and her mother, Mary Aiton, runs a hotel at Balmain. [44] Mrs Wakely does not look happy. Her husband is still paying 10 shillings a week to Bridget Torpy, their ex-servant, as child support for her illegitimate son, James, after an 'incident' when his wife was away for the weekend. Originally Torpy had been awarded 15 shillings but this had been reduced on appeal. Torpy's predicament was not unusual. The birth of her son would have prevented her finding work, making application to the courts imperative. Wakely has not learned his lesson and will face court again in 1860, when he will be fortunate to be acquitted of raping Bridget Kennedy, who, with her husband, James, will be working in the hotel. [45]

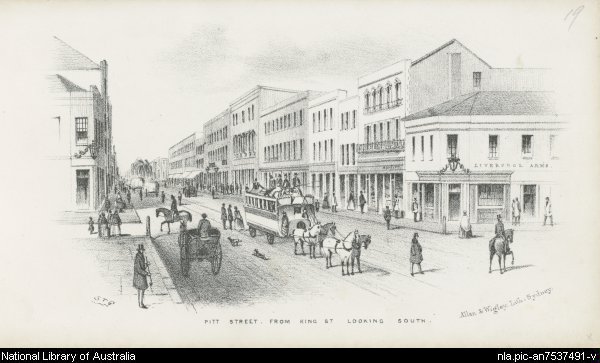

Block Three: Market Street to Park Street

There is less of a female presence in the next block. Mrs Catherine Wilcox, Miss Mary Ann Bray and Mrs Mary Anne Capp each own properties on the left, [46] while at the other end of the street Ann Ritchie owns her own house as well as the shops on either side. Widowed in 1849, she also owns property in the Hunter region and has taken an active part in managing it. Ritchie will continue to live in Pitt Street for several years until her death in 1865, when she will be remembered as 'an old and respected colonist'. [47] She will leave a large estate of £6,000, which she will take great care to distribute precisely as she wished in a very long and detailed will. [48]

[media]Closer to this end of the block is Edward Curtis's paperhanging business. He also lends space to Louise Dutruc and her husband, Pierre, who advertise French classes at the same address. The Dutrucs have been in Sydney for several years, having spent 12 years before that teaching French in Glasgow. Pierre Dutruc also has a wine and spirit business in Sydney and is the author of a French grammar book. In addition to their own private lessons, both the Dutrucs teach French at various local private academies. [49] They are eminently respectable. Pierre Dutruc will be a city councillor for Randwick between 1867 and 1871, will act briefly as the French Consul, and Dutruc Avenue in Randwick will be named after him. Louise Dutruc will continue to operate her own schools for at least the next 20 years, and her second name, Eulalie, will be given to another Randwick street. [50]

Across from the Dutrucs lives Jane Higgins, next to milliner Augusta Jane Bynon and her small children. Mrs Bynon is a woman who has been forced to rely upon her own skills to survive because she has had bad luck in the colony. Born in Middlesex, the daughter of artist Ben Baldwin, Augusta Baldwin worked as a milliner in some of the 'first London establishments' before emigrating. She married Walter Fayers in 1850 and together they established Suffolk House, a drapery store in George Street, with the new Mrs Fayers taking charge of the millinery department, as well as giving birth to a son and a daughter in quick succession. Augusta Fayers's first bad luck arrived when Walter Fayers died of consumption in 1853. His estate of £1,700 was partially tied up although his wife was given access to much of it while she carried on the business. [51] Her daughter also died in the same year. [52] She married William Bynon in 1855 and he took over the advertisements. Mrs Bynon was active in the business, and also added another daughter to her family. William Bynon went back to England in January 1857 and the business struck trouble in April, with auctioneers advertising the selling off of 'the entire stock in trade of Mrs Bynon'.

Augusta Bynon's bad luck continued with the wreck of the Dunbar off Sydney Heads in August 1857 as her husband, William, was a passenger on board and drowned intestate, leaving only £200. This was when Augusta Bynon and her three young children moved to a new Suffolk House in Pitt Street, where she continues her millinery and dressmaking business. In 1859 Augusta Bynon will finally have some good luck when she marries her third husband, John Walker, a watch and clock manufacturer. In about 1862 they will return to London, where John Walker will join his father's established watchmaking business in Regent Street. The couple will have three more daughters, born in New South Wales, France and England, and by 1881 Augusta Walker will be living in Kensington in London, with her husband and three of her daughters, as well as two domestic servants, having managed to make her way both back to England and up in society. [53]

Continuing down the street past Brandon's millinery warehouse, where several cap milliners are employed, there is the upholstery business of Joseph Sly, who employs several needlewomen. [54] Off to the side is the entrance to 'Charlotte Place'. This used to be known as Dick's Yard, when owned by Alexander Dick, but was presumably renamed by his widow, Charlotte, when she inherited it. [55] One of her tenants is laundress Margaret Tunk, who is still recovering from her recent brawl with a neighbouring laundress over the use of the communal washing line. Tunk successfully sued her neighbour and was awarded 10 shillings. [56]

Further down the block in Pitt Street are the more genteel Mrs Lees and Miss Cotton, whose straw bonnet-making business is nicely non-gender specific in the 1858–9 trade directory; like 'Doak and Kerr' in 1857, they are listed as 'Lees and Cotton'. Jane Lees and Ann Cotton are sisters who emigrated together from Staffordshire, with Jane's husband and daughter and their older sister and mother in 1853. Ann, Emma and Sarah Cotton were all described as domestic servants on the passenger list, but in fact 'Cotton and Lees' had a straw-hat business in Staffordshire in England. Five years later, Ann and Jane still have a good business. Jane Lees will die in 1862 but Cotton will continue in partnership with her brother-in-law until his marriage in 1866 to Eliza Dickie, a rival dressmaker. [57] Cotton's dressmaking business will survive George Lee's defection and she will still be in business 10 years later, before getting married in her sixties and continuing to advertise as Mrs Hamilton. [58]

[media]On the opposite side of the street from Lees and Cotton is the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, not a place that one would think to find many women, except accompanying their husbands to the occasional lecture. However, the next advertised lecture is to be given by Mrs Foster in just a few weeks, about establishing a home for respectable female emigrants. Caroline Dexter spoke there in 1855 and Madame Cramer gave a concert there in July 1856. At the end of 1858, the soon-to-be-notorious Cora Ann Weekes will make her debut. [59] Weekes has been flitting her way around the United States and is about to arrive in the Australian colonies. 'Interesting, lovely and intellectual,' she establishes quasi-feminist newspapers, collects subscriptions and prints a few issues, before disappearing into the night with her husband. They will be last heard of en route to Calcutta in the 'very superior and fast sailing' Glen Isla under false names in 1859. [60]

Block Four: Park Street to Bathurst Street

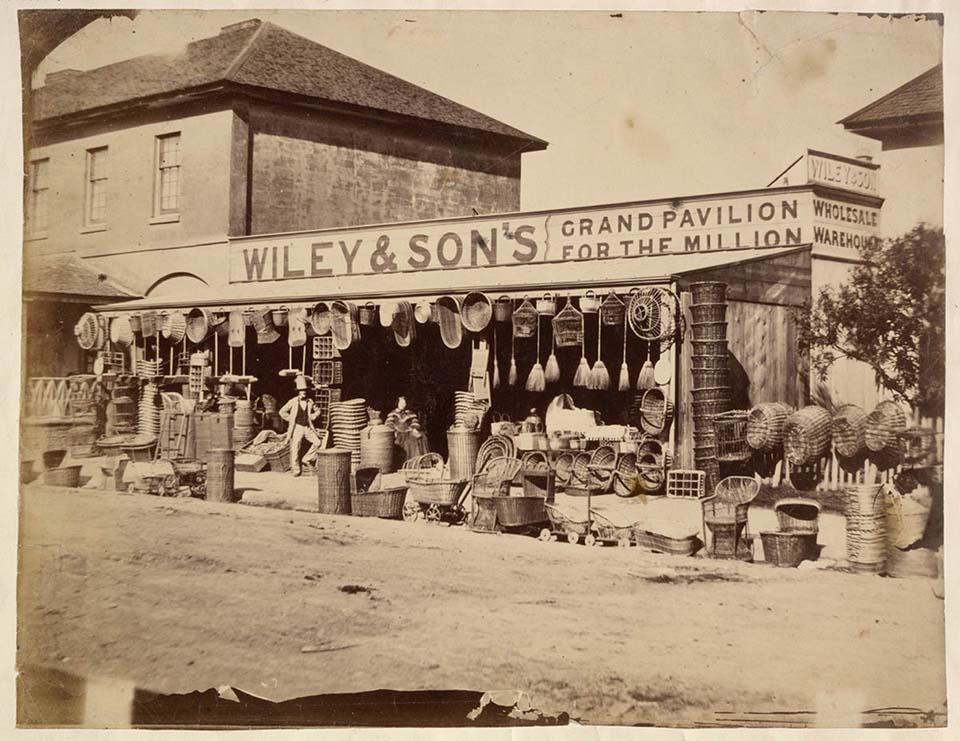

On the [media]corner of Pitt and Park streets is the photographer, William Blackwood, setting up to take a picture of one of another two buildings owned by Rosetta Terry. The photograph is of Wiley and Son's wholesale basket warehouse. [61] Posing alongside the proprietorial David Wiley is not his son, however, but his wife, Hannah, who, like many other wives, is often to be seen working in the family business. She will go so far as to advertise it herself in 1862. [62] The family emigrated a few years previously, having run a business in Oxford Street, London; they have several children ranging in age from two to 13. David Wiley has flair, as can be seen from his outfit in the photograph, and his advertisements are usually in the form of rhyming verse. Unfortunately this is not matched by his business ability, and he will go insolvent three times in the 1860s. [63] In addition to assisting in the business, Hannah Wiley is also active in the church and will contribute a decorated basket for raffling in support of the organ fund at St Andrew's Cathedral in 1865. [64]

Like the Wileys, Mary Ann and William Stephens, just down the road, used poetry to advertise their combined businesses:

If you should a bedstead need

Or a pleasant book to read

We can either want supply

If to us you will apply... [65]

The books were supplied by Mrs Stephen's circulating library, which has only recently closed, having been there since the beginning of the decade. [66] The bedsteads are still being made in her husband's iron bed manufactory. [67]

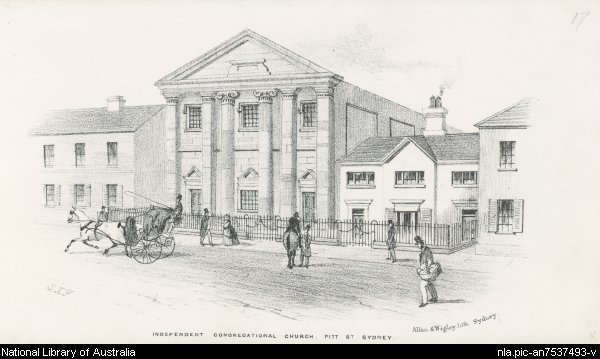

Elizabeth Ayton, the [media]teacher at the Congregational school, lives next door but one, with her house painter husband, William. Originally from Windsor in England, this couple followed their married son to Sydney as assisted immigrants in 1857, with three more nearly grown children. They are expecting another son and his wife to join them this year. Ayton is the wife and mother of men with a flourishing trade, a family business which will continue for many years. Nevertheless, she also teaches at the Congregational School and will do so until 1859. She will open her own school in 1860, which will last until at least 1867, which is the next time Mrs Ayton earns an independent listing in the trade directories. She will still be there in 1870. [68] One of her neighbours in 1858 is one of Miss Bray's tenants, Margaret Donohue, wife of butcher James Donohue. Widowed in 1863 with several young children, [69] she will demonstrate the transnational mobility of so many immigrants, marrying again in Honolulu in 1871. [70]

On the other side of Pitt Street is another butcher, Jane Jolly, next to the appropriately named Butcher's Arms Hotel. Jolly took over the business after her husband died in 1854, leaving her with six children under 11. She is in the process of selling the shop to Margaret Watson, who has been running a similar shop in Castlereagh Street, after the death of her own butcher husband, James. [71] Strolling past the house of fruiterer Mrs Rose Davis, one nods to Elizabeth Wright, who is preparing for her forthcoming marriage to John Cummings and move to Sussex Street. [72] Elizabeth Jeffries used to live next door running another fruit shop and offering dressmaking services, but she has moved on in the last few months. Further down the street is Mrs Mary Donohue, a milliner and dressmaker, who also cleans and dyes feathers. [73] She will be in business for the next two decades, moving from Pitt to Castlereagh to William streets, [74] where she will remain until her death in 1888. George Hattersley's cabinet-making business is in this block. His daughter, Margaret, will eventually take over Maria Robertson's lace-cleaning business. [75]

Maria Robertson lives across the street, and her lace-cleaning business is longstanding. She was once forewoman of 'Her Majesty's Lace Cleaners' in London, and has been in business in Sydney since 1850. Her husband had a parallel business cleaning men's clothes until his death. There was a kerfuffle in 1850 when Robertson moved her business from Pitt to Castlereagh Street

in consequence of certain individuals professing the same business, tempted by her high reputation, having borrowed the same name, in Pitt Street, in order to mislead the public, whereby mistakes have arisen, and great dissatisfaction has been caused. [76]

Today, her neighbour, Mrs Wright, the wife of the painter and paperhanger on the corner of Bathurst Street, is standing outside the lace cleaner's door, perhaps negotiating with the older woman, whose business she will take over in 1859, before passing it on to Margaret Hattersley, two years later. [77]

Between Robertson and Wright on the east side of Pitt Street is cabinetmaker Richard Seddon, with several unmarried daughters, at least one of whom works as a dressmaker, and has done since 1851. Another daughter will become a public school teacher. Their self-sufficiency is fortunate, for their father will end up in debtors' prison in 1868, apparently as a result of his wife's drinking habits. She will run up a bill at the grocery store of Ann Doodson. In spite of being a married woman at a time when the law of coverture still applied, [78] Doodson will then sue Richard Seddon, who is by then ill and stone-deaf. Seddon will die insolvent in 1884, leaving his unmarried schoolteacher daughter to take responsibility. [79] On the other corner of Bathurst and Pitt streets is the Edinburgh Castle hotel, once run by Sarah Doran (in 1854) and now by Phillip Steer. In a few short months he will be dead and his widow Jane will become the licensee in March 1859. Three years later, another woman, Sarah Joseph, will take over the pub. [80]

Block Five: Bathurst Street to Liverpool Street

At the top of the rise in Pitt Street and crossing over Bathurst Street and heading down towards Liverpool Street, 14 of the 70 properties in this block are owned by five different landladies. On the east side, Maryann Chapman and Mary Cannon each own their own homes and next-door properties. Mrs Elliot has one property and Jane Coates is the landlady of the pub on the corner of Liverpool Street as well as the two neighbouring shops. On the other side of the street, all eight properties down to Wilmot Street are owned by Lucy Hyndes, inherited from her much older husband when he died in 1855 aged 77. [81] One of her properties is the Cottage of Content pub, the license of which Martha Samson transferred to Joseph Woods in late 1856. [82] She then moved to Upper Fort Street, where she is running a boarding house to support herself and her children. [83] Hyndes's tenants also include Susan Paul, who could be the Deptford schoolmistress who emigrated in 1852 at the age of 52 with six children, aged from three to 19, or possibly the housemaid Susan Paul from Devon, who emigrated in 1855 aged 22. [84] Next door are saddler George Stone and his wife Mary, who is a milliner and dressmaker. The Stones have been in Sydney since 1849 and in Pitt Street since at least 1855. Mary Stone is a well-travelled colonial, having been born in Jamaica. They will be eminently respectable residents of Pitt Street until the 1870s and are strong advocates of temperance. At the time of her death in 1881, Mary Ann Stone will be treasurer of the 'No 27 Division, Daughters of Temperance, Advance Rose of Australia'. [85]

Tenants in this part of Pitt Street seem to change over fairly quickly. The Stones' neighbour, governess Miss Brown, who was here last year, has moved on and they will shortly gain another new neighbour, Mrs Scholey. Like Mary Stone, Rosa Scholey was born in Jamaica. She married Thomas Scholey there in 1835 and the couple migrated to England sometime before 1851, when they were living in Islington, Thomas working as a florist's salesman. In 1855 Rosa Scholey emigrated to New South Wales and through the 1860s and 1870s was the proprietor of a newsagent's, a registry office and a boarding house, dying in 1893. Meanwhile Thomas Scholey, 10 years older than his globetrotting wife, was last heard of as an inmate of St Mary's workhouse in Islington in 1861. [86] Catherine Richardson is also a new resident in this block. Her neighbours include fireman George Atkins and his wife, who is a 'monthly nurse', looking after new mothers and their babies. Although they will move to Bent Street by 1860, with George Atkins becoming a lamplighter, his wife will continue her profession for at least another decade. [87]

Mary Gorman and her husband, Hugh, have a greengrocer's shop nearby. There are at least two Hugh Gormans in Sydney during this period, although this is probably the convict, Hugh, who arrived in 1837. He has appeared regularly before the courts and was in prison for assault in 1857, leaving his wife with the shop to run, as well as their several young children. She is now pregnant again. [88] There are two more fruit and vegetable shops in this collection of buildings, one run by Mrs Lewis and the other by George Scotton's wife. Neither of these businesses, nor that of dressmaker Mrs Goldsmith, will be here in a year's time. Nearer the Liverpool Street end of the block are Isabella Dodwall's residence and a boarding house which used to be run by Mrs Stewart next to another under the care of Mrs Ross. Strolling down this block a year ago, there would have been fruiterer Mrs Simmonds and her neighbour Mrs McCann, a dressmaker, as well as Bridget Hickey and Lucy Hillier, who died recently. Sarah Wakely, who had a tripe shop in the Markets, also lived here, but they are no longer in evidence, although Mary Bowers, mother of butcher William Bowers, is still here and Amelia Dubbs and Mrs Isabella McTaggart, a schoolteacher in the National School, have just moved in. [89] Isabella McTaggart will suffer a reversal of fortune over the next decade. By 1865 she will be living in Macquarie Street, blaming her lodgers' unexpected departure for her insolvency. Her downward spiral is indicative of the precariousness of economic survival during this period. [90]

As well as being full of short-term residents, the properties in this block mainly house small-scale one-person businesses. There is not the same crowd of young milliners and saleswomen as there is further back along Pitt Street. Nevertheless, it is probable that there is at least one barmaid working in one of the five hotels in the block.

Block Six: Liverpool Street to Goulburn Street

Crossing over Liverpool Street, Mary Dick lives close by. Mrs Dick owns her own house, as well as the coach house next door. Eighty-year old Ann Sewell is at no 408, having won the right to reside here by evicting her widowed daughter-in-law in a bitter court battle the previous year. The younger Mrs Sewell had paid her rent for seven years by doing washing for her mother and sister-in-law. [91] Next door used to be a fruit shop run by Mrs Theresa Burridge a few months ago, but now it is the home of Mrs Rachel Moss, a general dealer, who has moved from York Street. Having had a confectioner's licence in her own name, Burridge will shortly marry another Pitt Street resident, Isaac Norris. After his sudden death in 1864, she will assume control of his well-established ginger beer manufactory. A force to be reckoned with, she will run the business for another decade. [92]

Miss Jane Barber owns the next property. On the other side of the street Charlotte Ellard, landlady of the aptly named Charlotte Place in the previous block, owns four more properties, inherited from her latest husband. Ellard is the daughter of convict William Hutchinson, who managed to crawl his way up the social and economic ladder, using what could politely be called 'enterprising' techniques. In 1826 his daughter married a free immigrant, the jeweller and silversmith Alexander Dick. Charlotte Dick served in the shop and continued the business for three years after his death in 1843, before selling up and marrying music seller and composer, Francis Ellard, a widower, who lived next door. Ellard was not as canny in business as Charlotte's first husband or Charlotte herself, and Charlotte Ellard found her own money under threat when he became insolvent. Ellard died in 1854 and his widow successfully manages her various properties. When she dies in 1875 she will leave an estate of around ₤2,000. [93] Further down the street lives MA (Mary Ann?) Reynolds. The high voices of the young ladies in Sarah Jones's school next door drift out into the street. Mrs Jones is no doubt happy not to be competing with Mrs Chandler, who moved her neighbouring ladies' school around the corner to Goulburn Street several months ago. Jones's school will still be operating in 10 years time. [94] At the end of the block at Goulburn Street is James Stewart's Australian Hotel on the corner, for which the barmaid's position was recently advertised. [95]

The end of the road: Goulburn Street through to George Street

Across the street on the other western corner of Pitt Street is another pub, The Sportsman, run by Timothy Cowell. He took over the license from his father-in-law Thomas Kelsey three years ago, and will be insolvent by 1860. His wife Frances will sue him successfully for child support and maintenance of 30 shillings a week after she is 'compelled to leave his house by ill treatment'. [96] He will fail to pay and be imprisoned in October. [97] With the support of her father (or possibly her brother, also called Thomas), who resumes the license, Frances will continue to run that pub and then another, leaving an estate of over £500 when she dies in 1886. [98]

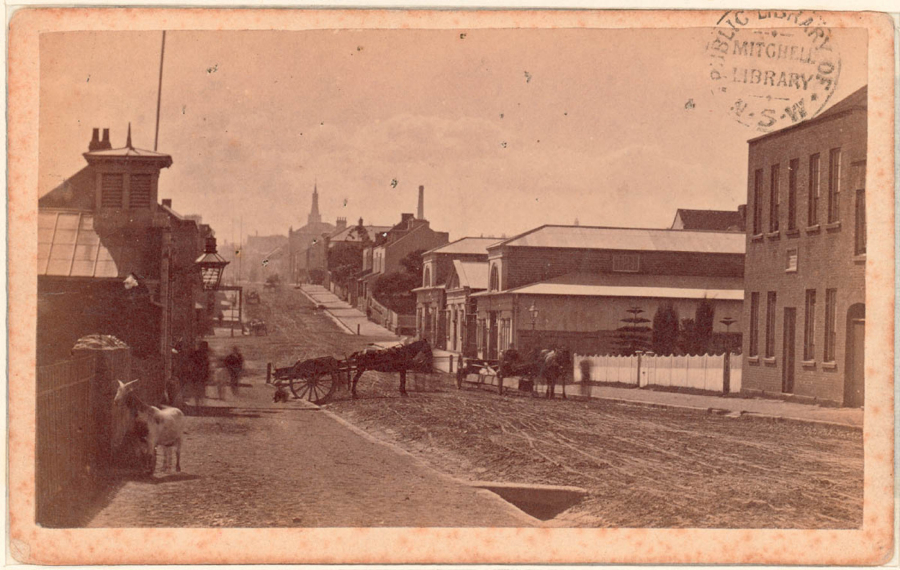

[media]There are only a handful of properties in these blocks, including one owned by Mary Stone and a boarding house run by Mrs Cook. Then comes the house of Mrs E Turner, widow of John and mother of Joseph, both farriers. Joseph will take over the business in 1859. At no 442, Mrs TM Edwards is hard at work. She has been an upholsterer for at least the last five years, having moved from Bank Street recently. [99] Three doors down, Mrs Mitchell and Mrs Whitby advertise their services as midwives and monthly nurses. [100] Perhaps some of Mesdames Mitchell and Whitby's business is at the Refuge for Destitute Females in the next block, under the watchful eye of the matron, Mrs Baker. Sarah Mitchell arrived in Sydney in 1853 as a 42-year-old assisted immigrant from Portland in Dorset. A monthly nurse and midwife in Portland, her move to Sydney has been one of geography rather than career. She also takes in lodgers and will go so far as to sue one unfortunate young woman in 1864; dressmaker Annie Cox will fail to pay her two-year-old debt of £40 to Mitchell and end up in Darlinghurst debtors' gaol. [101] Next is the intersection with George Street and ahead, past the Benevolent Asylum, is a type of no man's land, beyond which Pitt Street resumes life in Redfern.

It is clear from our walk down Pitt Street that in spite of the sparse female presence in the trade directories, in reality the street is alive with busy women, not only as domestic servants, but as property owners, independent tenants, employees and small-scale businesswomen. They are predominantly in the needlework and retail trades, especially those involving food and drink, although there are some teachers, and others manage their own properties. Their businesses are small, like those of many of their male counterparts.

The stories of some of these women show just how varied were their experiences. They are also representative of the wider Sydney population. There are those who have transported existing family businesses and husband-and-wife partnerships from Britain, women like milliners Doak and Kerr, the language-teaching Dutrucs, and the lace-cleaning Robertsons. There are widows who have taken over their husband's businesses, for varying lengths of time and with varying degrees of success, like jeweller and property owner Charlotte Ellard and publican Harriet Rubsamen.

There are also very many women hidden behind their husband's names; Mrs William Robson, Eliza Hudson, Hannah Wiley and Emily Way, all of whom are obvious to their contemporaries but whose contribution to the business will be lost over time. There are the women whose working lives extend beyond and between second and third marriages, such as Augusta Baldwin/Fayers/Bynon/Walker. And there are the eminently respectable, such as Louise Dutruc and Mary Ann Stone, temperance committee member, as well as the unfortunates, such as Mary Gorman and Ann Wakely, and the survivors, like Frances Cowell, whose husbands are less than satisfactory in so very many ways. Then there are the colourful characters, skirting the edges of respectable society, such as actress Mrs Guerin and dressmaker 'Madame' de Lolle, along with the downright dishonest, like conwoman Cora Ann Weekes, and the utterly unrespectable, such as Caroline Pope, brothel keeper. And finally there are the eternally elusive women; Mary Webb, whose business lasted at least 12 years and perhaps longer, but the details of whose life are a mystery, along with the scores of other women who remain just names on the pages of a directory, appearing briefly, like Amelia Dubbs, or for years, like Mrs Sarah Jones, school teacher, but equally invisible.

So while the official listings in the directories and rates assessment books show a mere handful of women's names, closer inspection reveals far more. And if so many women can be hidden in Pitt Street in plain view in 1858, just imagine how many more are boldly strolling the rest of Sydney's thoroughfares, with property to rent, services to offer and goods to sell in those years.

References

Katrina Alford, Production or Reproduction?: An Economic History of Women in Australia, 1788–1850, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1984

Margaret Anderson, 'Good Strong Girls: Colonial Women and Work' in Kay Saunders and Raymond Evans (eds), Gender Relations in Australia: Domination and Negotiation, Harcourt Brace, Sydney, 1992

Patricia Clarke, Pen Portraits: Women Writers and Journalists in Nineteenth Century Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

Desley Deacon, Managing Gender: The State, the New Middle Class and Women Workers 1830–1930, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989

Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, Sydney 1870–90, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987

Raelene Frances, Selling Sex: A Hidden History of Prostitution, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 2007

''Patricia Grimshaw, Marilyn Lake, Ann McGrath and Marian Quartly, Creating a Nation, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1994

Patricia Grimshaw, Chris McConville and Ellen McEwen, Families in Colonial Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985

Barry Higman, Domestic Service in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002

Margaret James, Margaret Bevege and Carmel Shute, Worth Her Salt: Women at Work in Australia, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1982

Grace Karskens, The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1998

Grace Karskens, Inside the Rocks: the archeology of a neighbourhood, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1999

Max Kelly (ed), Nineteenth-Century Sydney, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1978

Beverley Kingston, My Wife, My Daughter, and Poor Mary Ann: Women and Work in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1975

Diane Kirkby, Barmaids: A history of women's work in pubs, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1997

Maria Nugent, 'An Historical Overview of Women's Employment and Professionalism in Australia: Themes and Places', Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra, 2002

Monica Perrott, A Tolerable Good Success: Economic Opportunities for Women in New South Wales 1788–1830, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1983

Portia Robinson, The Hatch and Brood of Time: A Study of the First Generation of Native-Born White Australians 1788–1828, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985

Portia Robinson, The Women of Botany Bay: A Reinterpretation of the Role of Women in the Origins of Australian Society, revised edition, Penguin, Ringwood, Victoria, 1993

Edna Ryan and Anne Conlon, Gentle Invaders: Australian Women at Work, Penguin, Ringwood, Victoria, 1989

Glenda Strachan and Lindy Henderson, 'Assumed but Rarely Documented: Women's Entrepreneurial Activities in Late Nineteenth Century Australia', in The Past is Before Us. Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Sydney, 2005

Marjorie R Theobald, Knowing Women: Origins of Women's Education in Nineteenth-Century Australia, Studies in Australian History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996

Clare Alice Wright, Beyond the ladies lounge: Australia's female publicans, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2003

Notes

[1] For example: Raelene Frances and Melanie Nolan, 'Gender and the Trans-Tasman World of Labour: Transnational and Comparative Histories,' Labour History 95, 2008; Melanie Nolan, Breadwinning: New Zealand Women and the State, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, NZ, 2000; Patricia Grimshaw, John Murphy, and Belinda Probert, Double Shift: Working Mothers and Social Change in Australia, Circa, Beaconsfield, Victoria, 2005; Edna Ryan and Anne Conlon, Gentle Invaders: Australian Women at Work, second edition., Penguin, Ringwood Victoria, 1989; Beverley Kingston, My Wife, My Daughter, and Poor Mary Ann: Women and Work in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1975; Raelene Frances, Selling Sex: A Hidden History of Prostitution, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2007; Margaret James, Margaret Bevege and Carmel Shute, Worth Her Salt: Women at Work in Australia, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1982; Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, Sydney 1870–90, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987; Max Kelly (ed) Nineteenth-Century Sydney, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1978. This is partly because sources for this later 'long twentieth century' are more readily available and accessible than records for the earlier period. Work in New South Wales on the period before 1830, focussing on convict women, includes: Portia Robinson, The Women of Botany Bay: A Reinterpretation of the Role of Women in the Origins of Australian Society, revised edition, Penguin, Ringwood Victoria, 1993; Portia Robinson, The Hatch and Brood of Time: A Study of the First Generation of Native-Born White Australians 1788–1828, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1985; Monica Perrott, A Tolerable Good Success: Economic Opportunities for Women in New South Wales 1788–1830, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1983. There are exceptions, particularly more recently. For example; Glenda Strachan and Lindy Henderson, 'Assumed but Rarely Documented: Women's Entrepreneurial Activities in Late Nineteenth Century Australia,' in The Past is Before Us, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Sydney, 2005; Grace Karskens The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1998; Grace Karskens, Inside the Rocks: the archaeology of a neighbourhood, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1999; Maria Nugent, 'An Historical Overview of Women's Employment and Professionalism in Australia: Themes and Places', Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra, 2002; Margaret Anderson, 'Good Strong Girls: Colonial Women and Work' in Kay Saunders and Raymond Evans (eds), Gender Relations in Australia Domination and Negotiation, Harcourt Brace, Sydney, 1992; Both Anderson and Alford, whose work broke new ground when it was published in 1984, emphasise domestic service as an occupation and while acknowledging the presence of female businesswomen, did not have the resources to do so more than in passing. Katrina Alford, Production or Reproduction?: An Economic History of Women in Australia, 1788–1850, Oxford University Press, 1984

[2] Katrina Alford, Production or Reproduction?: An Economic History of Women in Australia, 1788–1850, Oxford University Press, 1984

[3] Barry Higman, Domestic Service in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2002

[4] Patricia Grimshaw, Chris McConville and Ellen McEwen, Families in Colonial Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985; Patricia Grimshaw et al, Creating a Nation, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1994; Clare Wright, Beyond the Ladies Lounge: Australia's Female Publicans, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2003; Kathryn McKerral Hunter, Father's Right-Hand Man: Women on Australia's Family Farms in the Age of Federation, 1880s–1920s, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2004; Marjorie R Theobald, Knowing Women: Origins of Women's Education in Nineteenth-Century Australia, Studies in Australian History, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996; Diane Kirkby, Barmaids: A history of women's work in pubs, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1997

[5] Desley Deacon, Managing Gender: The State, the New Middle Class and Women Workers 1830–1930, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989

[6] Census of the Colony of New South Wales 1861, available online at http://hccda.anu.edu.au/documents/NSW-1861-census

[7] Katrina Alford, Production or Reproduction?: An Economic History of Women in Australia, 1788–1850, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1984

[8] National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past website, http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz , National Library of Australia, Trove Digitised Newspapers and More website, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/home

[9] Most letters and diaries, which are predominantly written by women with leisure, when they mention women at all, mention other middle-class women in terms of respectability and state of wedded bliss, or, if working class, as potential or dreadful domestic servants. See for example Louisa Anne Meredith, Notes and Sketches of New South Wales: During a Residence in the Colony from 1839 to 1844, Ure Smith in association with The National Trust of Australia (NSW), 1973. As an indication of exactly how invisible women's work was, a working milliner and dressmaker in Sydney in the 1830s has left a diary which makes no mention of her work. Phebe Tilney Hayman, Diary 1806–47, 1852, privately held by Mrs Katherine Christian, Sydney

[10] Almost all of the women in the paper have been listed in one or more of the following sources: Cox and Co, Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, Cox, Sydney,1857; Sands' Sydney Directory, John Sands, 1858–1900; 'City of Sydney Assessment Books 1845–1948', 1858–59, available online at http://www3.photosau.com/CosRates/scripts/home.asp. They have been followed up using National Library of Australia, Trove Digitised Newspapers and More website, http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/home and New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages, Historical indexes online at http://www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/familyHistory/searchHistoricalRecords.htm, State Records New South Wales Indexes online, HYPERLINK "http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-online" http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-online, and assorted other online (and offline) resources, detailed in the footnotes.

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 January 1855, 27 July 1855, 25 August 1857, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, Historical indexes, Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857. She married George H Hocek or George Heady, according to Sydney Morning Herald, 25 August 1857 and New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages Historical indexes respectively

[12] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857

[13] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857. Mary Ann Mop married Thomas Brown in 1865

[14] Ann Makins, nee Gunner, in 1834 married Thomas, who died 1854 aged in 67. They had several children. She died in 1872 aged 63. Sydney Morning Herald, 25 May 1872, Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 December 1855, 4 January 1856, 25 July 1857, 6 March 1858, 19 April 1859; Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857, Sands' Sydney Directory 1858-9, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 December 1857. Unlike some others in her profession, Madame de Lolle was known for demanding a premium from parents of new apprentices, but by 1863 only Monsieur de Lolle was listed in the directory. Sydney Morning Herald 5 June 1857, Sands' Sydney Directory 1863. Perhaps she continues in business under another name. Emile de Lolle regularly advertised his French lessons until in 1872 he was sentenced to two years imprisonment for forging a cheque. Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 1872

[16] Susan Achison married John Glue in 1854. They had five children (one every two years) before her death in 1866. In 1862 the family moved to Concord on account of Susan's health. New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; Sydney Morning Herald, 7 June 1854, 8 April 1859, 27 August 1862, 12 July 1866

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 May 1848, 30 January 1855, 4 September 1858, 25 May 1872

[18] Sands' Sydney Directory; Sydney Morning Herald, 17 August 1865

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 March 1851, 1 March 1858, 18 November 1859

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 March 1859

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 March 1859, 22 December 1860, Sands' Sydney Directory 1861

[22] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory 1857, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 1851,

[23] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1858

[24] Harriet Mary Brown married a baker, John Rubsamen, in 1850. In 1855 John Rubsamen changed businesses and obtained the licence of the Settler's Arms in Castlereagh Street. He died in October 1857 and his widow, having lost her youngest child in January 1858, transferred this licence to another publican and instead took up the licence of the Glebe Tavern in Pitt Street. By the end of 1858 she was at the Elephant and Castle on the corner of King and Pitt streets. William Camb remained the licensee of the Elephant and Castle until 1867, moving to a new hotel in Castlereagh Street by 1870. They had a son (who died young) and a daughter. William died in 1880 and Harriet in 1888. New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1850, 5 September 1855, 6 October 1857, 13 March 1858, 16 November 1858, 14 December 1858; Sands' Sydney Directory,1858, 1861, 1863, 1865, 1867, 1870

[25] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857; Sands' Sydney Directory 1858-9; Sydney Morning Herald, 16 April 1857

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 January 1858

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 June 1858

[28] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 March 1859, 30 August 1859, 24 October 1859, 29 May 1861, 30 May 1861, 1 July 1861,

[29] See police reports for example, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 1867, 26 November 1867

[30] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 July 1856

[31] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 1857

[32] Joseph Fowles, Sydney in 1848, J Fowles, Sydney, 1848, p 93; Sydney Morning Herald, 18 January 1881

[33] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 May 1856, 14 August 1857

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 July 1845, 7 January 1854, 30 January 1860, 4 June 1879, 20 July 1904; New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes

[35] This is indicated by the number of advertisements for shopwomen and apprentices, milliners, dressmakers, improvers and first hands. For example milliners, cap milliners and saleswomen at Brandons, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 May 1857, 31 July 1857, 24 March 1858, milliners at Parry and Halberts, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 April 1857, 4 August 1857, at Farmers, Williams and Giles, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 July 1857, at Robinson and Morey, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 December 1857, at S Clark, Sydney Morning Herald,12 December 1857, 24 March 1858

[36] New Directory of the City of Londonderry and Coleraine, Including Strabane with Lifford, Newtownlimavady, Portstewart and Portrush, FR and G Kinder, Derry, 1839, pp 22–3, 32–3

[37] Margaret Doak was the mother of five children. Miss Rebeccah Kerr arrived aged 24 on the Crescent in 1840 with her sisters, Elizabeth (20, died 1841?) and Mary (19, married a Mr Pearce 1849?), brother John (18, carpenter) and father, Patrick (56, labourer). 'Indexes to assisted immigrants', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants; Crescent, 1840, 'Online' microfilm of shipping lists, State Records New South Wales website, HYPERLINK "http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/nrs-lists/nrs-5316" www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/nrs-lists/nrs-5316; Doak and Beattie, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 December 1873; Doak retired and Beattie sold off stock, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 October 1882; Mrs Beattie advertised at Wynyard Square address, where her mother and aunt died, until 1888, then moved to George Street by 7 December 1889

[38] New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes, Margaret Doak died aged 85, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 December 1883, Rebecca Kerr died, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 May 1884

[39] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1867, p 1

[40] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 February 1857; the several Mrs Webbs included Jane Webb, now in Riley Street, who survived insolvency in 1856 and by 1859 there was also another Mrs Webb advertising as a milliner in Denham Street. There was also Mrs Webb at 99 King Street, unusual because she did not live on her business premises but in Pyrmont. One of these was perhaps the other Mrs Webb of the original partnership

[41] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 January 1914, 4 March 1865, 8 November 1865, 19 July 1867

[42] Sydney Herald, 21 August 1839, 'The Romance of Farmer's', Sydney Morning Herald, 14 September 1940, p 11. Thirty-two years later the entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography gave slightly more credit to Caroline Farmer, writing that she 'opened a dressmaking and millinery shop,' but implied that the drapery shop subsequently run by her husband was a completely separate enterprise. GP Walsh, 'Farmer, Sir William (1832–1908),' in Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 4, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972, online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/farmer-sir-william-3498/text5371, accessed 24 August 2011

[43] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 September 1852; died 1868, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 July 1868

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 May 1851, 16 April 1853, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes

[45] This must have been particularly hard for Ann Wakely whose sons from her first marriage both died as babies. Her second marriage was childless. She died in 1867. New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1854, 8 December 1855, 4 August 1857, 10 February 1860, 11 February 1860, 15 April 1867, 'Publicans' Licenses 1830–61', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/publicans-licences

[46] Catherine Wilcox was the widow of Zachariah Thomas Wilcox, who died in 1850. He had been in the 32nd Regiment and then a shoemaker, from 1834. They had at least eight daughters and one son, three of whom died young. Catherine Wilcox died in 1870, leaving her estate of £100 to be divided between just two of her daughters, causing the rest of the family to challenge her will unsuccessfully in court. New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; Sydney Herald, 13 January 1834; Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1851, 14 January 1854,13 May 1865, 14 June 1865, 11 August 1885, 6 October 1865

[47] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 January 1865. When one of her horses was stolen in 1855 she advertised that she would know the horse when she saw it, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1855

[48] 'Ann Ritchie Probate Packet Date of Death 1 January 1865, Granted on 30 January 1865,' State Records New South Wales

[49] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 April 1854, 6 June 1854, 21 February 1855, 19 January 1857, 28 March 1857, 15 January 1858, 9 March 1858, 27 January 1859

[50] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1853, 'Councillors from 1859,' Randwick City Council website, 'Randwick Street Names A-F,' HYPERLINK "http://www.randwick.nsw.gov.au/About_Randwick/Heritage/History_of_the_Randwick_area/Street_park_and_place_names/Street_names_A_to_F/index.aspx" http://www.randwick.nsw.gov.au/About_Randwick/Heritage/History_of_the_Randwick_area/Street_park_and_place_names/Street_names_A_to_F/index.aspx , viewed 24 August 2011

[51] 'Walter Kemp Fayers Probate Packet Date of Death 4 December 1853 Granted on 18 January 1854,' State Records New South Wales

[52] New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes

[53] She died in 1907, aged 82. FreeBMD website, http://www.freebmd.org.uk/; Sydney Morning Herald, 16 July 1850, 21 September 1852, 6 December 1853, 2 July 1855, 18 March 1856, 1 April 1857, 25 August 1857, 4 November 1857, 25 November 1862, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; UK Census 1881 and other databases at Familysearch website, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, HYPERLINK "http://www.familysearch.org" www.familysearch.org

[54] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 April 1853

[55] City of Sydney, Assessment Book, Sydney,1858. See also other years.

[56] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 July 1858

[57] 'Indexes to assisted immigrants', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants, George Lees chemist and druggist in High Street in Tunstall, Staffordshire and Cotton and Lees straw bonnet makers 58 Rathbone Street, Tunstall, Staffordshire in William White, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire, Printed for William White by Robert Leader, Independent Office, Sheffield UK, 1851; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 June 1862, 20 March 1866, 7 April 1866, 22 June 1861

[58] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 April 1871, 8 August 1873; New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 1876, 9 December 1876

[59] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 February 1855, 2 July 1856, 22 March 1858, 31 December 1858

[60] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 January 1859; Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 12 February 1859; Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 22 February 1859; Moreton Bay Courier, 2 March 1859, Patricia Clarke, Pen Portraits: Women Writers and Journalists in Nineteenth Century Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1988

[61] William Blackwood, 'Wiley & Son's[Basket Wholesale Warehouse, Park Street, Sydney/ by William Blackwood], photograph, 1858, held State Library of New South Wales

[62] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 December 1862

[63] In 1860, 1863 and 1868 see 'Insolvency Index Compiled from Nrs 13656 Supreme Court Insolvency Index 1842-87,' State Records New South Wales, www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/bankruptcy-insolvency-records/index-to-insolvency-records

[64] Sydney Morning Herald,12 August 1865

[65] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 July 1855

[66] Sydney Morning Herald,17 November 1849, 23 September 1850, 14 November 1857

[67] Ford's Sydney Commercial Directory for the Year, 1851

[68] Beejapore, Rose of Sharon, Forest Monarch passenger lists 'Indexes to assisted immigrants', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants, Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857; Sands' Sydney Directory, Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1857, 27 October 1860, 12 May 1874, 2 November 1878

[69] New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes

[70] Sydney Morning Herald,10 June 1871

[71] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857

[72] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 October 1858

[73] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 June 1861, 31 January 1877; Sands' Sydney Directory, 1863, 1865, 1867 1870

[74] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 August 1868, 16 January 1888

[75] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 June 1861

[76] Sydney Morning Herald,25 April 1850, 6 July 1850, 13 September 1850, 14 October 1850, 31 August 1850, 18 March 1851, 19 February 1852 15 April 1854

[77] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 December 1858, 19 June 1861

[78] The law of coverture essentially meant that women could not operate independently of their husbands. They were not supposed to sue or be sued and could not go into debt.

[79] Ford's Sydney Commercial Directory for the Year, 1851; Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857, 'Richard Seddon,' in Supreme Court Insolvency Files, 20 October 1868, State Records New South Wales

[80] 'Publicans' Licenses 1830–61', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/publicans-licences

[81] 'Thomas Hyndes Probate Packet Date of Death 8 February 1855 Granted on 21 March 1855,' State Records New South Wales

[82] 'Publicans' Licenses 1830–61', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/publicans-licences

[83] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June 1857

[84] 'Indexes to assisted immigrants', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants, Humboldt 1852 or Hungerford 1855 'Online' Microfilm of Shipping Lists, State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/nrs-lists/nrs-5316

[85] 'Indexes to assisted immigrants', State Records New South Wales website, HYPERLINK "http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants" http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants, Kate, 1849, 'Online' Microfilm of Shipping Lists, State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/nrs-lists/nrs-5316, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 August 1880

[86] Jamaica Church of England Parish Register Transcripts 1664-1880, Manchester Baptisms, Marriages and Burials 1816–1836 at Familysearch website, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, www.familysearch.org; '; Light of the Age 1855, 'Online' microfilm of Shipping Lists, State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/guides-and-finding-aids/nrs-lists/nrs-5316; Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 1860, 30 May 1863, 5 March 1881; UK census records for 1851 and 1861 at Familysearch website, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, www.familysearch.org;

[87] Sands' Sydney Directory, 1867

[88] Empire, 9 October 1851, 23 October 1851, 21 May 1855, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 March 1857, New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes

[89] New South Wales Births, Deaths and Marriages, online indexes; Sydney Morning Herald, 29 December 1854, Bowers; 'William Bowers Probate Packet Date of Death 2 April 1857, Granted on 12 June 1857', State Records New South Wales

[90] Sydney Morning Herald 19 June 1858, 5 March 1859, 'Isabella MacTaggart, Macquarie Street, Boarding House Keeper', in Supreme Court Insolvency Files 1865, State Records New South Wales

[91] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 August 1857

[92] Theresa Cottrell arrived from County Cork on the Calcutta with her sister and married brother in 1838. She apparently married convict Benjamin Burridge although no record has been found and upon her second marriage she used the name Cottrell. Burridge died in 1852. Theresa Burridge held a confectioner's licence in 1857. She married the widowed Norris in 1860 and after his death was quick to advertise her independence in business. She even fired her own sons in 1869. She was fined for using insulting language to Martha Veney in 1866 and she was forced to make a public apology after slandering Mr J Cannon in 1863. The cordial business was sold off in 1874. Theresa Norris died in 1878. Index to Bounty Immigrants Arriving in NSW, Australia, 1828–1842, at Familysearch website, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, www.familysearch.org; Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1840, 17 December 1857, 25 February 1860, 23 March 1863, 22 April 1863, 24 July 1863, 9 November 1863, 14 March 1867, 16 November 1868, 2 February 1869, 17 June 1878; Empire, 24 November 1866, 6 April 1867, New South Wales Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages, Historical indexes online at http://www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/familyHistory/searchHistoricalRecords.htm

[93] John Wade, 'Dick, Alexander (c1791–1843)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, supplementary volume, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005, online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dick-alexander-12886/text23277, viewed 24 August 2011. Paul Edwin Le Roy, 'Hutchinson, William (1772–1846),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 1 Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1966, online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hutchinson-william-2217/text2879, accessed 24 August 2011; The Australian, 9 May 1834; 'Francis Ellard George St Music Seller,' in Supreme Court Insolvency Files,18 November 1842, State Records New South Wales; 'Francis Ellard George St Sydney Dealer in Music,' in Supreme Court Insolvency Files 20 February 1847, State Records New South Wales; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 December 1846, 10 May 1849, 27 March 1857, 15 July 1875; 'Charlotte Ellard Probate Packet Date of Death 14 July 1875, Granted on 18 August 1875,' State Records New South Wales

[94] Sands' Sydney Directory, 1857-1870

[95] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1858

[96] Empire, 19 May 1860

[97] Empire, 6 October 1860, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 October 1860

[98] 'Publicans' Licenses 1830–61', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/publicans-licences; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 February 1855, licence to Thomas Kelsey 6 September 1860, Licence of Fortune of War George Street from Margaret Moore to Francis (sic) Cowell; 25 January 1871, licence of Sydney and Goulburn Hotel, Pitt Street from Frances Cowell to S Erdis; 28 January 1871, 28 January 1872 'Frances Cowell Probate Packet Date of Death 31 January 1886, Granted on 6 May 1886', State Records New South Wales

[99] Cox and Co's Sydney Post Office Directory, 1857, Waugh and Cox's Directory of Sydney and Its Suburbs, 1855

[100] Sydney Morning Herald, 4 March 1854, 8 March 1858, 16 April 1858, 2 September 1858

[101] http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records/indexes-to-assisted-immigrants, Talavera,1853 'Online' Microfilm of Shipping Lists', State Records New South Wales website, http://www.records.nsw.gov.au/state-archives/indexes-online/indexes-to-immigration-and-shipping-records; UK census records for 1841 and 1851 at Familysearch website, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, www.familysearch.org; 'Ann Cox, Sempstress', in Supreme Court Insolvency Files 1864, State Records New South Wales